Abstract

mRNA vaccines have been increasingly recognized as a powerful vaccine platform since the FDA approval of two COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, which demonstrated outstanding prevention efficacy as well as great safety profile. Notably, nucleoside modification and lipid nanoparticle-facilitated delivery has greatly improved the immunogenicity, stability, and translation efficiency of mRNA molecule. Here we review the recent progress in mRNA vaccine development, including nucleoside modification, in vitro synthesis and product purification, and lipid nanoparticle vectors for in vivo delivery and efficient translation. We also briefly introduce the clinical application of mRNA vaccine in preventing infectious diseases and treating inflammatory diseases including cancer.

Keywords: mRNA vaccines, Lipid nanoparticle, In vitro transcription, Cancer vaccine, Neoantigen

Messenger RNA (mRNA) was identified as the intermediate carrying genetic information form DNA to ribosomes for protein synthesis in 1961 (Brenner et al., 1961). After the in vitro transcription (IVT) method for RNA production was developed, scientists started to use mRNA to express desired protein in mouse (Krieg and Melton, 1984; Wolff et al., 1990). In theory, mRNA molecules inside the host cells would use the host translation machinery to produce protein and execute the desired physiological function. However, initially application of mRNA to express protein in vivo was hampered by the instability of mRNA in vivo and inherited inflammatory nature of mRNA with unmodified nucleotides. As the delivery technology quickly advanced in the recent years, and the development of nucleoside modification to avoid innate immune recognition, the applications of mRNA technology in biomedical field have been quickly expanding (Sahin et al., 2014). Vaccine is probably the most well-known field among the many applications, thanks to the excellent performance of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) mRNA vaccines recently approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Vaccine is nearly the most powerful weapon for human beings to battle bacteria- or virus-caused infectious diseases. Traditional vaccines are often made with live-attenuated or inactivated pathogens, or subunit antigens derived from pathogens. Traditional vaccines have been successful in preventing infectious diseases such as small pox, polio, etc., but the development and large-scale production could be time-consuming, which may not applicable for sudden outbreak of infectious diseases such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and COVID-19. By contrast, mRNA can be quickly designed and synthesized, and the sequences can be modified according to the need for controlling viral variants. In addition, mRNA doesn't integrate into genome, thereby avoid the potential mutagenic risk. Using lipid nanoparticle-delivered mRNA encoding SPIKE antigen derived from SARS-COV-2 virus, two mRNA vaccines developed by BioNtech/Pfizer and Moderna Inc. have shown excellent prevention efficacy with good biosafety profile, which lead to unprecedented fast approval for human use by FDA (Chaudhary et al., 2021). In this chapter, we briefly summarize the recent progress in mRNA vaccine development, including mRNA design, delivery tools, and clinical applications.

1. Messenger RNA synthesis and modification for vaccine

mRNA vaccine is composed of targeted sequence encoding antigen and delivery system for intracellular release. The synthetic mRNA produced by in vitro transcription has a similar structure of natural mRNA, including 5′ cap, 5′UTR (untranslated region), nucleoside-modified ORF (open reading frame), 3′UTR, and poly(A) tail (Fig. 1 ), to overcome the problem in stability, translational efficacy as well as unwanted immunogenicity.

Fig. 1.

The structure components of IVT mRNA. In-vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA contains five structural elements: 5′cap, flanking 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs), open reading frame (ORF) encoding the antigen and a poly(A) tail.

1.1. 5′Cap structure

In eukaryotes transcription, 7-methylguanosine (m7G) binds to the 5′ end of mRNA via 5′-5′ triphosphate to form a cap structure. The cap makes eukaryotic transcription initiation factor 4e (eLF4e) binding to initiate transcription, and at the same time prevents mRNA degradation induced by exonuclease Xrn1p. Besides, 5′cap works synergistically with the following mentioned “poly(A) tail” to enhance RNA stability (Mockey et al., 2006). There are two major strategies for capping in an IVT reaction, one is enzymatic capping post transcription; another one is capping simultaneously by additional cap analog in transcription mixture. Because of the easy reverse orientation of m7G to 5′ nucleotides of mRNA via 3′-5′ phosphodiester, which reduces translation efficiency, anti-reverse cap analogues (ARCA) were developed in the past decades, such like P(1)-3′-deoxy-7-methyguanosine-5′ P3-guanosine-5′ triphosphate and P(1)-3′-O,7-dimethylguanosine-5′ P3-guanosine-5′ triphosphate (Stepinski et al., 2001). ARCA are made by chemical modification on m7G including the replacement of 3′-OH into the 3′O-Me or the 3′deoxy substitution of oxygen molecule of the triphosphate bridge into sulfur, borane or selenium (Grudzien-Nogalska et al., 2007). Those ARCA are also resistant to decapping enzyme hydrolysis (Grudzien-Nogalska et al., 2007; Kowalska et al., 2008; Kuhn et al., 2010), benefiting mRNA stability and protein production.

1.2. UTRs

Untranslated regions (UTRs) flanking the ORF can bind with various regulatory protein and thus affect encoded protein translational efficacy. The sequence, length and secondary structure of UTR all affect mRNA translation efficacy. The presence of encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) within the 5′UTR even facilitate a 5′cap-independent protein expression pathway (Elroy-Stein et al., 1989; Tan and Wan, 2008). UTRs used in the synthetic RNA is usually from α/β-globin, human heat shock protein or virus. However, UTR performance may vary between cell types, and customized design of specific UTR for targeted cell type is necessary. Differ from 5′UTR, 3′UTR is more inclined to maintain the stability of mRNA and indirectly enhance gene expression.

1.3. Poly(A) tail

Polyadenylation naturally occurrs at the 3′ end of majority mRNAs in a co-transcriptional fashion and plays a critical role in transcript function and cell biology. On the one hand, poly(A) tail mediates the cytoplasm translocation of mature mRNA (Natalizio and Wente, 2013). On the other hand, poly(A) tail regulates translation efficiency and controls mRNA degradation (Bresson and Conrad, 2013; Wu et al., 2013). Poly(A) tailing of IVT mRNA can be accomplished either by enzymatic polyadenylation after IVT mixture or by cloning a poly(T) tail into the DNA template. The length of the poly(A) tail affects the translation efficiency of mRNA. Generally, longer poly(A) tail exhibits a higher promotion effect in protein translation. It was reported that antigen-coding sequence with a poly(A) tail (not longer than 120 bases) increased intracellular antigen protein expression and yield higher protein translation efficacy, thus improved T cell stimulatory capacity of dendritic cells (Holtkamp et al., 2006; Linares-Fernandez et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). However, longer length is not always better, and recent findings suggest that 30-neucleotides length is likely the minimum length needed for cytoplasmic poly(A) binding protein binding and efficient translation (Gohin et al., 2014; Lima et al., 2017; Passmore and Coller, 2022). Further work is needed to decipher the detailed mechanism of poly(A) tail in mRNA stability and translation regulation for better mRNA design for efficient protein expression.

1.4. Nucleoside modification

The core of mRNA vaccine is the coding region expressing target protein antigen. Sequence modification within ORF is also required to elicit strong immune response. A strategy to enhance protein expression efficiency is codon optimization. It is known that different organisms prefers different codons (Gouy and Gautier, 1982). Protein expression outside host might be very difficult for the rarely used codons in the desired host. Therefore, replacing rare codon with frequently used codons in desired host enhance protein expression (Gustafsson et al., 2004).

The host immune system recognizes unmodified single-stranded RNA and switch on anti-virus responses once exogenous RNA entry into cell, and exerts anti-mRNA effect such as causing the instability of mRNA and downregulating translation efficacy (Pollard et al., 2013). Chemical modification on nucleosides improves the bottleneck of mRNA therapy by downregulating RNA-mediated innate immune activation and maintaining mRNA stability. For example, Unmodified RNA stimulated pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7, TLR8,leading to the induction of potent IFNα/γ as well as IL-12 (Kariko et al., 2005). Strikingly, mRNA bearing modified nucleosides such as 2-thiouridine and 5-methyl-cytidine modification prevented immune response compared with unmodified RNA and dedicated a higher protein expression level in vivo (Kormann et al., 2011).

Virus invasion leads to double- stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) activation, translation initiation factor eIF2α subunit phosphorylation and production of 2′-5′ oligonucleotide synthase (OAS) and adenosinease (Pichlmair and Reis e Sousa, 2007). These downstream signals prevent virus replication, translation and promote exogenous nucleoside degradation. Based on virus depletion mechanism, modifications that help avoid enzymatic hydrolysis and translation inhibition are discovered. It is reported that 2′-O-methyl-U retain nuclease resistance, and incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA can increase translation capacity while avoiding PRR recognition and PKR activation (Kariko et al., 2008). Furthermore, purification of IVT mRNA by Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography (FPLC) or High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) would remove contaminated double-stranded RNA and greatly reduced PKR activation (Baiersdorfer et al., 2019; Weissman et al., 2013). Although some studies reported no discernible advantage of such nucleotide modification in mRNA translation (Kauffman et al., 2016; Thess et al., 2015), recent study confirmed that uridine modification and dsRNA impurity removal are the two most important factors determining the immunostimulating nature of synthesized mRNA (Nelson et al., 2020).

1.5. Self-amplifying RNA

There are two major types of RNA tested in vaccine application including self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) and non-replicating RNA (nrRNA). For traditional non-self-amplified mRNA, the expression level of encoded antigens depends on the number of copies of the delivered mRNA. In order to achieve stronger immune effect, it is necessary to increase the injection dose or frequency. Compared with nrRNA, saRNA has additional virus replication elemental between its 5′UTR and ORF. The viral replicase used in saRNA could be from alphaviruses, flaviviruses, measles viruses, and rhabdoviruses. Therefore, saRNA could produce a large amount of antigen protein and induce a strong immune response at a relatively small dosage. For example, Beissert et al. developed a trans-amplifying RNA vaccine, which in a nanogram was sufficient for inducing potent immune response (Beissert et al., 2020). However, due to the longer length, saRNA delivery is more challenging comparing to that of nrRNA (Lundstrom, 2018).

2. Carrier-mediated mRNA vaccine delivery

mRNA vaccine has shown therapeutic potential in preventing viral infection and treating inflammatory diseases including cancer. For in vivo administration, the most common injection routes for mRNA vaccines are intranodal (IN), intramuscular (IM), subcutaneous (SC), and intravenous (IV) administration (Chaudhary et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). Despite the different administration routes, the common targets are the lymphoid organs and immune cells such as antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Many methods have been investigated for delivering mRNA vaccines, such as carrier-mediated and dendritic cell-based. The dendritic cell-based mRNA vaccine is a kind of cell therapy involving mRNA transfection into in vitro cultured dendritic cells and infusion of cells back to patient body, and requires strict in vitro culture process. In this section, we focus on the advanced strategies for carrier-mediated mRNA vaccines delivery.

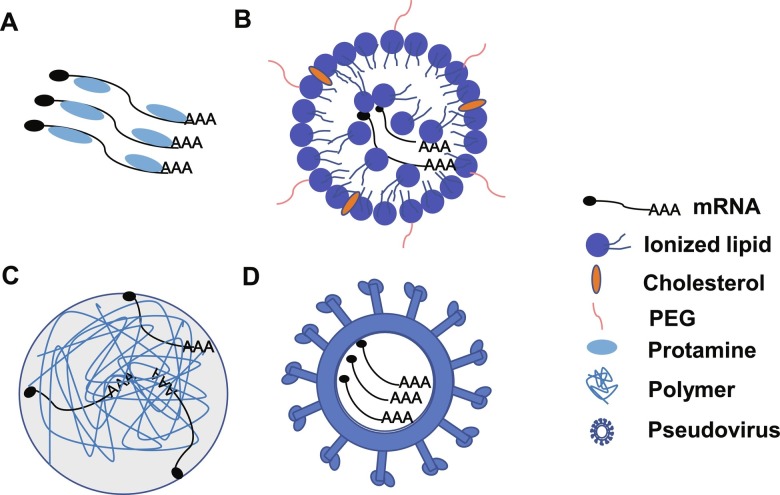

The carrier-formulated mRNA can be easily and efficiently engulfed and translated by APCs when injected in vivo. The most commonly used carriers are lipid-based, polymer-based, peptide-based and pseudovirus-based particles (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Cartoon illustration of different mRNA delivery carriers. (A) Protamine-based carrier; (B) Lipid nanoparticle-based carrier; (C) Polymer-based carrier; (D) Pseudovirus-based carrier.

2.1. Lipid-based delivery

Lipids have been applied for exogenous mRNA delivery owing to several advantages, such as protecting mRNA from enzymatic degradation and high delivery efficiency into cell cytosol (Midoux and Pichon, 2015; Richner et al., 2017a; Sabnis et al., 2018). The lipids usually contain three essential domains: a polar head group, a linker and a hydrophobic tail region, while the polar charged head was for electrostatic interaction with mRNA and the hydrophobic tail was for nanoparticle formation.

The 1,2-di-O-octadecenyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTMA), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), 2,3 dioleyloxy-N-[2-(sperminecarboxamido) ethyl]-N,N-dimethyl-1-propanaminium trifluoroacetate (DOSPA) and Ethylphosphatidyl choline (ePC) are commonly used cationic lipids serving for mRNA delivery (Brito et al., 2014; Kormann et al., 2011; Malone et al., 1989; Persano et al., 2017). DOTMA-mRNA lipoplexes can target spleen specifically and serve as a systemic cancer vaccine, which can be used for melanoma and colon cancer therapy (Kranz et al., 2016a). DOTAP-based nanoemulsions and DOTAP-polymer hybrid nanoparticle can deliver mRNA for the treatment of colon cancer and protection of multiple types of virus infection, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (Brito et al., 2014; Sahin et al., 2020a). DOSPA, which contains quaternary ammonium and spermine, can not only form mRNA complex but also stimulate innate immune responses, thereby serving as an immune adjuvant (Kormann et al., 2011). As another example, the engineered lipid-like material (synthesized through the ring opening of 1,2-epoxytetradecane by generation 0 of poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers with a different length of carbon tails) can deliver mRNA vaccine and potentiate antitumor efficacy through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling. Such lipid-like material-packaged mRNA nanoparticles showed efficient mRNA-encoded antigen expression and presentation, and induced the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 via stimulating TLR4 signal pathway in dendritic cells. Moreover, the nanovaccine exhibited significant antitumor efficacy in both tumor prevention and therapeutic vaccine settings (Zhang et al., 2021).

Ionizable lipids are positively charged at low pH, and they can improve the biocompatibility of lipid nanoparticles due to the less interactions with the anionic members of blood cells, and facilitate endosome escape. The MC3 and MC3-based engineered lipids such as L319 (used for RNA interference (RNAi) delivery), SM-102(used for intramuscular administration of mRNA vaccines) and ALC-0315 (used for nucleic acids delivery) show great mRNA delivery efficacy and pharmacokinetics (Maier et al., 2013). More importantly, the SM-102 and ALC-0315 are the critical ionizable lipid components for mRNA-1273 and BNT162b COVID-19 vaccines, respectively (Baden et al., 2021; Vogel et al., 2021). Furthermore, the engineered ionizable lipid with a heterocyclic amine as head group can not only deliver the mRNA, but also active the STING (an critical innate immune sensor) signaling pathway in dendritic cells, thereby triggering the anti-tumor immune response (Miao et al., 2019).

In addition, the lipid helpers, such as DSPC, DOPE, cholesterol and polyethylene glycol (PEG) were often combined with ionizable lipids for mRNA delivery with different functions respectively. The DSPC could stabilize the structure of lipid nanoparticles (Koltover et al., 1998), which has been used in the mRNA-1273 and BNT162b COVID-19 vaccines (Baden et al., 2021; Polack et al., 2020). DOPE could destabilize the endosomal members and facilitate mRNA release into cytosol and was used for mRNA and siRNA delivery in vivo (Kauffman et al., 2015). Cholesterol can not only enhance the particle stability, but also affect the delivery efficacy and biodistribution of in vivo mRNA administration. For example, its analogues C-24 alkyl phytosterols increased the delivery efficacy of lipid nanoparticle (LNP) mRNA in vivo (Eygeris et al., 2020). PEG affects the lipid nanoparticle in multiple aspects, such as the nanoparticle formation, avoiding nanoparticle aggregation and prolonging the blood circulation of particles via providing a hydrophilic outer layer, and has been commonly applied for nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery in vitro and in vivo (Knop et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2017).

Overall, lipid-based carriers could overcome multiple barriers and are often used for in vivo delivery of mRNA vaccine due to many benefits, such as enhanced mRNA stability, long circulating time, high fusion capacity with cellular membranes and endosome escape. The rapid approval of LNP-formulated mRNA vaccines against COVID19 has witnessed the rapid development, robust protection efficacy and good safety profile of such vaccines. Nevertheless, there are minor side effects reported, which may be attributed to the inflammatory nature of the lipid components in the vaccine. With further investigation, lipid-based barriers may facilitate the development of more effective mRNA vaccines and therapeutic drugs while avoiding unwanted side effect.

2.2. Polymer-based delivery

Polymers are also widely used for mRNA delivery and offer similar advantages of lipids. Polyethylenimine (PEI), polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer and polysaccharide are the most commonly used polymers for mRNA delivery (Chahal et al., 2016; Moghimi et al., 2005). The PEI-packaged HIV gp120 mRNA vaccine can trigger high levels of specific antibodies against HIV infection in mice, but the in vivo toxicity impedes its clinically application (Li et al., 2016; Moyo et al., 2019). The PAMAM dendrimer with the self-amplifying mRNAs vaccine can protect mice from Ebola, H1N1 and Zika virus infection (Chahal et al., 2016). In addition, the poly(aspartamide)s conjugated with ionizable aminoethylene, which can be charged at acidic pH, also lead to a high mRNA delivery and rapid release of the mRNA from endosome to cytosol (Kim et al., 2019). Overall, polymer-based mRNA delivery showed good delivery efficiency, but their use is limited by obvious toxicity. Further studies may need to focus on the structure modification or combination with other helper materials to mitigate the polymer toxicity without sacrificing the delivery efficacy.

2.3. Peptide-based delivery

Peptides has also been applied for mRNA delivery owing to the cationic or amphipathic amine groups, such as arginine, which can electrostatically bind to the negatively charged mRNA and form nanocomplex (McCarthy et al., 2014). The RALA peptide, which contains repetitive arginine-alanine-leucine-alanine (RALA) motifs, can condense mRNA into nanoparticle, and transfect DCs and elicit T cell-mediated immune response (Li et al., 2004). Anionic peptides conjugated to positively charged polymers was also used for delivering mRNA into antigen presenting cells efficiently and specifically, and triggered antigen presenting cells activation (Lou et al., 2019). In addition, protamine was also used as cationic peptide for mRNA delivery, as it can protect mRNA from RNase degradation and active TLR7 as an adjuvant (Kallen et al., 2013; Skold et al., 2015). The mRNA vaccines which based on protamine-formulated delivery have been in clinical trials for treating multiple cancer types including prostate cancer (CV9103 and CV9104) and non-small cell lung cancer (CV9201), but the in vivo immune response was too weak for tumor control (Kubler et al., 2015; Papachristofilou et al., 2019; Weide et al., 2009). Therefore, further development of peptide-based mRNA vaccine is needed to improve the magnitude of in vivo immune response.

2.4. Pseudovirus-based particles

Pseudovirus can be utilized for mRNA delivery which refers the RNA virus structures (Lundstrom, 2020). The pseudovirus with mRNA shows high delivery efficiency to cell cytosol thanks to multiple cell entry pathways by the virus (Usme-Ciro et al., 2013). Moreover, some virus structure in the particles can trigger innate immune response, thereby serving as self-adjuvant purpose. The pseudovirus mRNA vaccines have been applied for preventing dengue virus infection and inhibiting tumor growth in mice (White et al., 2013), and the pseudovirus-based mRNA HIV vaccines have been under clinical evaluation (Fuchs et al., 2015). However, the viral-based mRNA delivery depends on packaging cell lines and needs to follow a special manufacturing process, which limits its large-scale production (Rauch et al., 2018). More importantly, the viral-based mRNA particles may induce unwanted antibody production as the virus structure can be recognized as antigen, which was reported in several clinical trials, such as the vaccine for cytomegalovirus and therapeutic cancer vaccine for patients with advanced cancer (Bernstein et al., 2009; Morse et al., 2010). Therefore, future development must focus on the streamline preparation and minimizing the anti-viral structure immunity.

Taken together, there are multiple types of carriers for mRNA delivery, which shows different benefits and shortages (Table 1 ). So far, lipid-based carriers have been most widely used with excellent delivery efficiency and great safety profile, but long-term monitoring of side effect is necessary to avoid any potential risk.

Table 1.

Summary of commonly used mRNA delivery carriers.

| Delivery format | Advantages | Challenges | Clinical application |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Lipid-based carriers |

mRNA stability Blood circulation Delivery efficacy Reproduction Scale up |

Potential side effects |

Approved for COVID-19 vaccine/Clinical trials for others |

| Polymer-based carriers | mRNA stability Delivery efficacy |

Toxicity | Preclinical mouse model |

| Peptide-based carriers | mRNA stability Adjuvant activity |

Low immune response | Clinical trial/Preclinical mouse model |

| Pseudovirus-based carriers | mRNA stability Deliver efficacy |

Scale up/Antibody to viral vectors | Clinical trials |

3. mRNA vaccines for clinical applications

Battling the global pandemic of SARS-COV-2, mRNA vaccines have gone from a small field to a widespread application, making a remarkable contribution to saving many lives. Compared to traditional vaccines, mRNA vaccines enable precise antigen design and production of proteins with “native-like” presentation, stabilized in more immunogenic conformations, expose key antigenic sites or protein antigens from different pathogens that results in a single vaccine targeting multiple targets (Gebre et al., 2021). Due to their outstanding advantages in delivering antigens and eliciting immune responses, mRNA vaccines have great potential in the treatment of many diseases. This section will focus on the applications and summarize the progress in preclinical and clinical trials of mRNA vaccines in recent years.

The application of mRNA vaccines can be roughly divided into three directions. First, it is applied to resist SARS-COV-2. The outbreak of SARS-COV-2 in the end of 2019 has caused a worldwide pandemic. At the forefront of the fight against Covid-19, mRNA vaccine products from different manufacturing companies have been used clinically or are still in clinical trials. The FDA-approved mRNA-1273 vaccine comes from Moderna Inc. and encodes transmembrane prefusion SPIKE protein of Covid-19 by nucleoside-modified mRNA (Corbett et al., 2020). The SPIKE protein on SARS-CoV-2 surface is an essential component for virus binding and uptake into mammalian cells (Letko et al., 2020). Vaccination with mRNA-1273 induced remarkable type 1 helper T cell (Th1)-biased CD4 T cell responses but weak Th2 or CD8 T cell responses and efficient neutralizing antibodies, which provides effective protection against SARS-CoV-2 (Baden et al., 2021; Corbett et al., 2020). Another mRNA vaccine that achieved colossal success clinically is BNT162b2 that manufactured by BioNTech and Pfizer (Tauzin et al., 2021). BNT162b2, a nucleoside-modified mRNA encapsulated in LNP that encodes SARS-CoV-2 SPIKE glycoprotein, can elicit a strong responses of IFNγ + or IL-2 + CD8 + T cells and CD4 + Th1 cells and induce high neutralizing antibody titres in serum from immunized individuals (Sahin et al., 2021). Other companies also have designed different mRNA vaccines. CVnCoV from CureVac uses unmodified mRNA to express full-length SPIKE protein and simultaneously activate innate immunity (Kremsner et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the clinical trial outcomes were not as good as the previous two mRNA vaccines, and the effective rate against Covid-19 was only 47%, according to their company statement. ARCT-021 from Arcturus Inc. uses self-amplifying mRNA to encode the full length of SPIKE protein, which also induced a strong Th1-dominant immune response and a robust viral antigen-specific CD8 + T lymphocyte response (de Alwis et al., 2021). LNP-nCoVsaRNA developed by Imperial College London and Acuitas Therapeutics uses self-amplifying mRNA to encode the SPIKE protein to provoke Th1-biased response against SARS-CoV-2 (McKay et al., 2020). ARCoV from Walvax biotechnology and Abogen Inc. uses unmodified mRNA to encode secreted spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) to elicit neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 as well as a Th1-biased cellular response in preclinical experiments (Zhang et al., 2020). So far, the two mRNA vaccines using LNP-delivered mRNA with nucleoside modification by Moderna Inc. and BioNtech Inc. exhibited robust efficacy and received FDA approval in an unprecedented speed.

In addition to SARS-COV-2, the prevention effect of mRNA vaccines was also tested against other infectious diseases, including cytomegalovirus, Zika, human metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, Influenza A, Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), and Rabies in preclinical animal experiments or clinical trials (Alberer et al., 2017; Chahal et al., 2016; Chaudhary et al., 2021; Kose et al., 2019; Magini et al., 2016; Richner et al., 2017b). Generally, these mRNA vaccines are injected into the skin, muscle, or subcutaneous space to transfer mRNA into antigen presenting cells that finally induce specific CD8 + T cell responses, robust polyfunctional Th1 cells, and antibody responses to resist virus (Chaudhary et al., 2021). The mRNA vaccine against CHIKV encodes a ultrapotent neutralizing human monoclonal antibody to treat CHIKV infection (Kose et al., 2019). Apart from fighting virus infection, mRNA vaccines have been reported to elicit immune responses against Plasmodium species or Streptococci infection (Baeza Garcia et al., 2018; Maruggi et al., 2017). Plasmodium express an ortholog of the mammalian cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor (PMIF), which modulates the host inflammatory response to malaria (Cordery et al., 2007; Dobson et al., 2009). The mRNA vaccine based on an RNA replicon encoding PMIF could reduce the expression of the Th1-associated inflammatory markers TNFα, IL-12, IFNγ, and augment T follicular helper cells and germinal center responses to increase anti-Plasmodium antibody titers (Baeza Garcia et al., 2018). In conclusion, the above results indicate that the mRNA vaccine has substantial application value in preventing infectious diseases caused by viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotic microorganisms.

Another vast potential application scenario for mRNA vaccines is cancer immunotherapy. Since 1995, there has been an attempt to use mRNA vaccine encoding carcinoembryonic antigen to elicit tumor antigen-specific immune responses in mice (Conry et al., 1995). Nowadays, multiple mRNA vaccines targeting different solid tumors like non-small-cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, melanoma, triple-negative breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and gastrointestinal cancer are in clinical trials (Burris et al., 2019; Cafri et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2021; Sahin et al., 2020b; Sebastian et al., 2014). With the fast development of nucleotide sequencing technology, individualized sequencing results from tumor patients have revealed many potential neoantigens. Neoantigens are tumor-specific and highly immunogenic antigens generated by genetic mutations on tumor cells and have great potential value for the design of tumor vaccines (Schumacher and Schreiber, 2015). For example, an mRNA vaccine called mRNA-4157 encoding up to 34 neoantigens was designed to induce neoantigen-specific T cells and associated anti-tumor responses to treat unresectable (locally advanced or metastatic) solid tumors and resected cutaneous melanoma (Burris et al., 2019). The novel mRNA vaccine against gastrointestinal cancer encoding defined neoantigens, predicted neoepitopes, and mutations of driver genes in a single mRNA construct can elicit mainly CD4 +, and not CD8 +, T cell-specific responses to inhibit tumor growth (Cafri et al., 2020). BNT111, an intravenously administered liposomal RNA vaccine for melanoma, can induce strong antigen-specific CD4 + and CD8 + T cell immunity by precisely and effectively targeting dendritic cells in various lymphoid compartments accompanied by TLR7-triggered interferon (IFN) α production (Kranz et al., 2016b; Sahin et al., 2020b).

To modify the very immunosuppressive nature of tumor tissue microenvironment, mRNA can also be used to express proinflammatory cytokines to tailor tumor microenvironment besides expressing tumor antigens. In a clinical trial (NCT03739931), mRNA 2752 encoding human OX40L, IL-23, and IL-36γ was administrated to induce a proinflammatory tumor microenvironment and to promote T cell expansion, infiltration, and memory responses to prevent tumor progression (Bauer et al., 2019; Patel et al., 2020). Recently, another fascinating study reported an mRNA-based chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy treating heart failure. By using mRNA complexed with CD5-targeted LNP to express the fibroblast activation protein alpha-CAR protein in mice, the researchers observed specific and strong killing of fibroblasts, reduce fibrosis and restored cardiac function after injury (Rurik et al., 2022).

The ability of encoding functional proteins has given mRNA therapies enormous potential in treating genetic diseases, autoimmune diseases and cancer immunotherapies. Altogether, evidenced by the success of mRNA vaccines for controlling SARS-COV-2 global pandemic, mRNA vaccines hold promise to revolutionize future vaccines for treating infectious diseases, cancer, and beyond (Chaudhary et al., 2021).

References

- Alberer M., Gnad-Vogt U., Hong H.S., Mehr K.T., Backert L., Finak G., Gottardo R., Bica M.A., Garofano A., Koch S.D., Fotin-Mleczek M., Hoerr I., Clemens R., von Sonnenburg F. Safety and immunogenicity of a mRNA rabies vaccine in healthy adults: an open-label, non-randomised, prospective, first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1511–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31665-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., Diemert D., Spector S.A., Rouphael N., Creech C.B., McGettigan J., Khetan S., Segall N., Solis J., Brosz A., Fierro C., Schwartz H., Neuzil K., Corey L., Gilbert P., Janes H., Follmann D., Marovich M., Mascola J., Polakowski L., Ledgerwood J., Graham B.S., Bennett H., Pajon R., Knightly C., Leav B., Deng W., Zhou H., Han S., Ivarsson M., Miller J., Zaks T., COVE Study Group Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeza Garcia A., Siu E., Sun T., Exler V., Brito L., Hekele A., Otten G., Augustijn K., Janse C.J., Ulmer J.B., Bernhagen J., Fikrig E., Geall A., Bucala R. Neutralization of the Plasmodium-encoded MIF ortholog confers protective immunity against malaria infection. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2714. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiersdorfer M., Boros G., Muramatsu H., Mahiny A., Vlatkovic I., Sahin U., Kariko K. A facile method for the removal of dsRNA contaminant from in vitro-transcribed mRNA. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2019;15:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer T., Patel M., Jimeno A., Wang D., McDermott J., Zacharek S., Randolph W., Johansen L., Hopson K., Frederick J., Zaks T., Meehan R.S. Abstract CT210: a phase I, open-label, multicenter, dose escalation study of mRNA-2752, a lipid nanoparticle encapsulating mRNAs encoding human OX40L, IL-23, and IL-36γ, for intratumoral injection alone and in combination with immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Res. 2019;79:CT210. [Google Scholar]

- Beissert T., Perkovic M., Vogel A., Erbar S., Walzer K.C., Hempel T., Brill S., Haefner E., Becker R., Tureci O., Sahin U. A trans-amplifying RNA vaccine strategy for induction of potent protective immunity. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D.I., Reap E.A., Katen K., Watson A., Smith K., Norberg P., Olmsted R.A., Hoeper A., Morris J., Negri S., Maughan M.F., Chulay J.D. Randomized, double-blind, phase 1 trial of an alphavirus replicon vaccine for cytomegalovirus in CMV seronegative adult volunteers. Vaccine. 2009;28:484–493. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., Jacob F., Meselson M. An unstable intermediate carrying information from genes to ribosomes for protein synthesis. Nature. 1961;190:576–581. doi: 10.1038/190576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresson S.M., Conrad N.K. The human nuclear poly(a)-binding protein promotes RNA hyperadenylation and decay. PLoS Genet. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito L.A., Chan M., Shaw C.A., Hekele A., Carsillo T., Schaefer M., Archer J., Seubert A., Otten G.R., Beard C.W., Dey A.K., Lilja A., Valiante N.M., Mason P.W., Mandl C.W., Barnett S.W., Dormitzer P.R., Ulmer J.B., Singh M., O'Hagan D.T., Geall A.J. A cationic nanoemulsion for the delivery of next-generation RNA vaccines. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:2118–2129. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris H.A., Patel M.R., Cho D.C., Clarke J.M., Gutierrez M., Zaks T.Z., Frederick J., Hopson K., Mody K., Binanti-Berube A., Robert-Tissot C., Goldstein B., Breton B., Sun J., Zhong S., Pruitt S.K., Keating K., Meehan R.S., Gainor J.F. A phase I multicenter study to assess the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of mRNA-4157 alone in patients with resected solid tumors and in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:2523. [Google Scholar]

- Cafri G., Gartner J.J., Zaks T., Hopson K., Levin N., Paria B.C., Parkhurst M.R., Yossef R., Lowery F.J., Jafferji M.S., Prickett T.D., Goff S.L., McGowan C.T., Seitter S., Shindorf M.L., Parikh A., Chatani P.D., Robbins P.F., Rosenberg S.A. mRNA vaccine-induced neoantigen-specific T cell immunity in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:5976–5988. doi: 10.1172/JCI134915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahal J.S., Khan O.F., Cooper C.L., McPartlan J.S., Tsosie J.K., Tilley L.D., Sidik S.M., Lourido S., Langer R., Bavari S., Ploegh H.L., Anderson D.G. Dendrimer-RNA nanoparticles generate protective immunity against lethal Ebola, H1N1 influenza, and toxoplasma gondii challenges with a single dose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:E4133–E4142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600299113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary N., Weissman D., Whitehead K.A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021;20:817–838. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conry R.M., LoBuglio A.F., Wright M., Sumerel L., Pike M.J., Johanning F., Benjamin R., Lu D., Curiel D.T. Characterization of a messenger RNA polynucleotide vaccine vector. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1397–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett K.S., Flynn B., Foulds K.E., Francica J.R., Boyoglu-Barnum S., Werner A.P., Flach B., O'Connell S., Bock K.W., Minai M., Nagata B.M., Andersen H., Martinez D.R., Noe A.T., Douek N., Donaldson M.M., Nji N.N., Alvarado G.S., Edwards D.K., Flebbe D.R., Lamb E., Doria-Rose N.A., Lin B.C., Louder M.K., O'Dell S., Schmidt S.D., Phung E., Chang L.A., Yap C., Todd J.M., Pessaint L., Van Ry A., Browne S., Greenhouse J., Putman-Taylor T., Strasbaugh A., Campbell T.A., Cook A., Dodson A., Steingrebe K., Shi W., Zhang Y., Abiona O.M., Wang L., Pegu A., Yang E.S., Leung K., Zhou T., Teng I.T., Widge A., Gordon I., Novik L., Gillespie R.A., Loomis R.J., Moliva J.I., Stewart-Jones G., Himansu S., Kong W.P., Nason M.C., Morabito K.M., Ruckwardt T.J., Ledgerwood J.E., Gaudinski M.R., Kwong P.D., Mascola J.R., Carfi A., Lewis M.G., Baric R.S., McDermott A., Moore I.N., Sullivan N.J., Roederer M., Seder R.A., Graham B.S. Evaluation of the mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in nonhuman Primates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1544–1555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordery D.V., Kishore U., Kyes S., Shafi M.J., Watkins K.R., Williams T.N., Marsh K., Urban B.C. Characterization of a Plasmodium falciparum macrophage-migration inhibitory factor homologue. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:905–912. doi: 10.1086/511309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alwis R., Gan E.S., Chen S., Leong Y.S., Tan H.C., Zhang S.L., Yau C., Low J.G.H., Kalimuddin S., Matsuda D., Allen E.C., Hartman P., Park K.J., Alayyoubi M., Bhaskaran H., Dukanovic A., Bao Y., Clemente B., Vega J., Roberts S., Gonzalez J.A., Sablad M., Yelin R., Taylor W., Tachikawa K., Parker S., Karmali P., Davis J., Sullivan B.M., Sullivan S.M., Hughes S.G., Chivukula P., Ooi E.E. A single dose of self-transcribing and replicating RNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine produces protective adaptive immunity in mice. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:1970–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson S.E., Augustijn K.D., Brannigan J.A., Schnick C., Janse C.J., Dodson E.J., Waters A.P., Wilkinson A.J. The crystal structures of macrophage migration inhibitory factor from Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium berghei. Protein Sci. 2009;18:2578–2591. doi: 10.1002/pro.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elroy-Stein O., Fuerst T.R., Moss B. Cap-independent translation of mRNA conferred by encephalomyocarditis virus 5′ sequence improves the performance of the vaccinia virus/bacteriophage T7 hybrid expression system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:6126–6130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eygeris Y., Patel S., Jozic A., Sahay G. Deconvoluting lipid nanoparticle structure for messenger RNA delivery. Nano Lett. 2020;20:4543–4549. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c01386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs J.D., Frank I., Elizaga M.L., Allen M., Frahm N., Kochar N., Li S., Edupuganti S., Kalams S.A., Tomaras G.D., Sheets R., Pensiero M., Tremblay M.A., Higgins T.J., Latham T., Egan M.A., Clarke D.K., Eldridge J.H., HVTN 090 Study Group and the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases HIV Vaccine Trials Network, Mulligan M., Rouphael N., Estep S., Rybczyk K., Dunbar D., Buchbinder S., Wagner T., Isbell R., Chinnell V., Bae J., Escamilla G., Tseng J., Fair R., Ramirez S., Broder G., Briesemeister L., Ferrara A. First-in-human evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus human immunodeficiency Virus-1 gag vaccine (HVTN 090) Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv082. ofv082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre M.S., Brito L.A., Tostanoski L.H., Edwards D.K., Carfi A., Barouch D.H. Novel approaches for vaccine development. Cell. 2021;184:1589–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohin M., Fournier E., Dufort I., Sirard M.A. Discovery, identification and sequence analysis of RNAs selected for very short or long poly a tail in immature bovine oocytes. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2014;20:127–138. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M., Gautier C. Codon usage in bacteria: correlation with gene expressivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:7055–7074. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.22.7055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudzien-Nogalska E., Jemielity J., Kowalska J., Darzynkiewicz E., Rhoads R.E. Phosphorothioate cap analogs stabilize mRNA and increase translational efficiency in mammalian cells. RNA. 2007;13:1745–1755. doi: 10.1261/rna.701307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C., Govindarajan S., Minshull J. Codon bias and heterologous protein expression. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp S., Kreiter S., Selmi A., Simon P., Koslowski M., Huber C., Tureci O., Sahin U. Modification of antigen-encoding RNA increases stability, translational efficacy, and T-cell stimulatory capacity of dendritic cells. Blood. 2006;108:4009–4017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X., Zaks T., Langer R., Dong Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater. 2021:1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00358-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallen K.J., Heidenreich R., Schnee M., Petsch B., Schlake T., Thess A., Baumhof P., Scheel B., Koch S.D., Fotin-Mleczek M. A novel, disruptive vaccination technology: self-adjuvanted RNActive((R)) vaccines. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2013;9:2263–2276. doi: 10.4161/hv.25181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariko K., Buckstein M., Ni H., Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariko K., Muramatsu H., Welsh F.A., Ludwig J., Kato H., Akira S., Weissman D. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1833–1840. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman K.J., Dorkin J.R., Yang J.H., Heartlein M.W., DeRosa F., Mir F.F., Fenton O.S., Anderson D.G. Optimization of lipid nanoparticle formulations for mRNA delivery in vivo with fractional factorial and definitive screening designs. Nano Lett. 2015;15:7300–7306. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman K.J., Mir F.F., Jhunjhunwala S., Kaczmarek J.C., Hurtado J.E., Yang J.H., Webber M.J., Kowalski P.S., Heartlein M.W., DeRosa F., Anderson D.G. Efficacy and immunogenicity of unmodified and pseudouridine-modified mRNA delivered systemically with lipid nanoparticles in vivo. Biomaterials. 2016;109:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Ogura S., Otabe T., Kamegawa R., Sato M., Kataoka K., Miyata K. Fine-tuning of hydrophobicity in amphiphilic Polyaspartamide derivatives for rapid and transient expression of messenger RNA directed toward genome engineering in brain. ACS Cent Sci. 2019;5:1866–1875. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop K., Hoogenboom R., Fischer D., Schubert U.S. Poly(ethylene glycol) in drug delivery: pros and cons as well as potential alternatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:6288–6308. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltover I., Salditt T., Radler J.O., Safinya C.R. An inverted hexagonal phase of cationic liposome-DNA complexes related to DNA release and delivery. Science. 1998;281:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kormann M.S., Hasenpusch G., Aneja M.K., Nica G., Flemmer A.W., Herber-Jonat S., Huppmann M., Mays L.E., Illenyi M., Schams A., Griese M., Bittmann I., Handgretinger R., Hartl D., Rosenecker J., Rudolph C. Expression of therapeutic proteins after delivery of chemically modified mRNA in mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:154–157. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kose N., Fox J.M., Sapparapu G., Bombardi R., Tennekoon R.N., de Silva A.D., Elbashir S.M., Theisen M.A., Humphris-Narayanan E., Ciaramella G., Himansu S., Diamond M.S., Crowe J.E., Jr. A lipid-encapsulated mRNA encoding a potently neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against chikungunya infection. Sci Immunol. 2019;4 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw6647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska J., Lewdorowicz M., Zuberek J., Grudzien-Nogalska E., Bojarska E., Stepinski J., Rhoads R.E., Darzynkiewicz E., Davis R.E., Jemielity J. Synthesis and characterization of mRNA cap analogs containing phosphorothioate substitutions that bind tightly to eIF4E and are resistant to the decapping pyrophosphatase DcpS. RNA. 2008;14:1119–1131. doi: 10.1261/rna.990208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz L.M., Diken M., Haas H., Kreiter S., Loquai C., Reuter K.C., Meng M., Fritz D., Vascotto F., Hefesha H., Grunwitz C., Vormehr M., Husemann Y., Selmi A., Kuhn A.N., Buck J., Derhovanessian E., Rae R., Attig S., Diekmann J., Jabulowsky R.A., Heesch S., Hassel J., Langguth P., Grabbe S., Huber C., Tureci O., Sahin U. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2016;534:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature18300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz L.M., Diken M., Haas H., Kreiter S., Loquai C., Reuter K.C., Meng M., Fritz D., Vascotto F., Hefesha H., Grunwitz C., Vormehr M., Hüsemann Y., Selmi A., Kuhn A.N., Buck J., Derhovanessian E., Rae R., Attig S., Diekmann J., Jabulowsky R.A., Heesch S., Hassel J., Langguth P., Grabbe S., Huber C., Türeci Ö., Sahin U. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2016;534:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature18300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremsner P.G., Mann P., Kroidl A., Leroux-Roels I., Schindler C., Gabor J.J., Schunk M., Leroux-Roels G., Bosch J.J., Fendel R., Kreidenweiss A., Velavan T.P., Fotin-Mleczek M., Mueller S.O., Quintini G., Schönborn-Kellenberger O., Vahrenhorst D., Verstraeten T., Alves de Mesquita M., Walz L., Wolz O.O., Oostvogels L. Safety and immunogenicity of an mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2: A phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2021;133:931–941. doi: 10.1007/s00508-021-01922-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg P.A., Melton D.A. Functional messenger RNAs are produced by SP6 in vitro transcription of cloned cDNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7057–7070. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubler H., Scheel B., Gnad-Vogt U., Miller K., Schultze-Seemann W., Vom Dorp F., Parmiani G., Hampel C., Wedel S., Trojan L., Jocham D., Maurer T., Rippin G., Fotin-Mleczek M., von der Mulbe F., Probst J., Hoerr I., Kallen K.J., Lander T., Stenzl A. Self-adjuvanted mRNA vaccination in advanced prostate cancer patients: a first-in-man phase I/IIa study. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2015;3:26. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0068-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn A.N., Diken M., Kreiter S., Selmi A., Kowalska J., Jemielity J., Darzynkiewicz E., Huber C., Tureci O., Sahin U. Phosphorothioate cap analogs increase stability and translational efficiency of RNA vaccines in immature dendritic cells and induce superior immune responses in vivo. Gene Ther. 2010;17:961–971. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letko M., Marzi A., Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:562–569. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Nicol F., Szoka F.C., Jr. GALA: a designed synthetic pH-responsive amphipathic peptide with applications in drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004;56:967–985. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zhao M., Fu Y., Li Y., Gong T., Zhang Z., Sun X. Enhanced intranasal delivery of mRNA vaccine by overcoming the nasal epithelial barrier via intra- and paracellular pathways. J. Control. Release. 2016;228:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima S.A., Chipman L.B., Nicholson A.L., Chen Y.H., Yee B.A., Yeo G.W., Coller J., Pasquinelli A.E. Short poly(A) tails are a conserved feature of highly expressed genes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:1057–1063. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares-Fernandez S., Moreno J., Lambert E., Mercier-Gouy P., Vachez L., Verrier B., Exposito J.Y. Combining an optimized mRNA template with a double purification process allows strong expression of in vitro transcribed mRNA. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;26:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou B., De Koker S., Lau C.Y.J., Hennink W.E., Mastrobattista E. mRNA Polyplexes with post-conjugated GALA peptides efficiently target, transfect, and activate antigen presenting cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2019;30:461–475. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom K. Self-replicating RNA viruses for RNA therapeutics. Molecules. 2018;23 doi: 10.3390/molecules23123310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom K. Self-amplifying RNA viruses as RNA vaccines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21145130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magini D., Giovani C., Mangiavacchi S., Maccari S., Cecchi R., Ulmer J.B., De Gregorio E., Geall A.J., Brazzoli M., Bertholet S. Self-amplifying mRNA vaccines expressing multiple conserved influenza antigens confer protection against homologous and Heterosubtypic viral challenge. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier M.A., Jayaraman M., Matsuda S., Liu J., Barros S., Querbes W., Tam Y.K., Ansell S.M., Kumar V., Qin J., Zhang X., Wang Q., Panesar S., Hutabarat R., Carioto M., Hettinger J., Kandasamy P., Butler D., Rajeev K.G., Pang B., Charisse K., Fitzgerald K., Mui B.L., Du X., Cullis P., Madden T.D., Hope M.J., Manoharan M., Akinc A. Biodegradable lipids enabling rapidly eliminated lipid nanoparticles for systemic delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:1570–1578. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone R.W., Felgner P.L., Verma I.M. Cationic liposome-mediated RNA transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:6077–6081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruggi G., Chiarot E., Giovani C., Buccato S., Bonacci S., Frigimelica E., Margarit I., Geall A., Bensi G., Maione D. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy induced by self-amplifying mRNA vaccines encoding bacterial antigens. Vaccine. 2017;35:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy H.O., McCaffrey J., McCrudden C.M., Zholobenko A., Ali A.A., McBride J.W., Massey A.S., Pentlavalli S., Chen K.H., Cole G., Loughran S.P., Dunne N.J., Donnelly R.F., Kett V.L., Robson T. Development and characterization of self-assembling nanoparticles using a bio-inspired amphipathic peptide for gene delivery. J. Control. Release. 2014;189:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay P.F., Hu K., Blakney A.K., Samnuan K., Brown J.C., Penn R., Zhou J., Bouton C.R., Rogers P., Polra K., Lin P.J.C., Barbosa C., Tam Y.K., Barclay W.S., Shattock R.J. Self-amplifying RNA SARS-CoV-2 lipid nanoparticle vaccine candidate induces high neutralizing antibody titers in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17409-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L., Li L., Huang Y., Delcassian D., Chahal J., Han J., Shi Y., Sadtler K., Gao W., Lin J., Doloff J.C., Langer R., Anderson D.G. Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases anti-tumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:1174–1185. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midoux P., Pichon C. Lipid-based mRNA vaccine delivery systems. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2015;14:221–234. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.986104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockey M., Goncalves C., Dupuy F.P., Lemoine F.M., Pichon C., Midoux P. mRNA transfection of dendritic cells: synergistic effect of ARCA mRNA capping with poly(a) chains in cis and in trans for a high protein expression level. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;340:1062–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghimi S.M., Symonds P., Murray J.C., Hunter A.C., Debska G., Szewczyk A. A two-stage poly(ethylenimine)-mediated cytotoxicity: implications for gene transfer/therapy. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:990–995. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse M.A., Hobeika A.C., Osada T., Berglund P., Hubby B., Negri S., Niedzwiecki D., Devi G.R., Burnett B.K., Clay T.M., Smith J., Lyerly H.K. An alphavirus vector overcomes the presence of neutralizing antibodies and elevated numbers of Tregs to induce immune responses in humans with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:3234–3241. doi: 10.1172/JCI42672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyo N., Vogel A.B., Buus S., Erbar S., Wee E.G., Sahin U., Hanke T. Efficient induction of T cells against conserved HIV-1 regions by mosaic vaccines delivered as self-amplifying mRNA. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019;12:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natalizio B.J., Wente S.R. Postage for the messenger: designating routes for nuclear mRNA export. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J., Sorensen E.W., Mintri S., Rabideau A.E., Zheng W., Besin G., Khatwani N., Su S.V., Miracco E.J., Issa W.J., Hoge S., Stanton M.G., Joyal J.L. Impact of mRNA chemistry and manufacturing process on innate immune activation. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz6893. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristofilou A., Hipp M.M., Klinkhardt U., Fruh M., Sebastian M., Weiss C., Pless M., Cathomas R., Hilbe W., Pall G., Wehler T., Alt J., Bischoff H., Geissler M., Griesinger F., Kallen K.J., Fotin-Mleczek M., Schroder A., Scheel B., Muth A., Seibel T., Stosnach C., Doener F., Hong H.S., Koch S.D., Gnad-Vogt U., Zippelius A. Phase Ib evaluation of a self-adjuvanted protamine formulated mRNA-based active cancer immunotherapy, BI1361849 (CV9202), combined with local radiation treatment in patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:38. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore L.A., Coller J. Roles of mRNA poly(A) tails in regulation of eukaryotic gene expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022;23:93–106. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00417-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M.R., Bauer T.M., Jimeno A., Wang D., LoRusso P., Do K.T., Stemmer S.M., Maurice-Dror C., Geva R., Zacharek S., Laino A.S., Sun J., Frederick J., Zhou H., Randolph W., Cohen P.S., Meehan R.S., Sullivan R.J. A phase I study of mRNA-2752, a lipid nanoparticle encapsulating mRNAs encoding human OX40L, IL-23, and IL-36γ, for intratumoral (iTu) injection alone and in combination with durvalumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:3092. [Google Scholar]

- Persano S., Guevara M.L., Li Z., Mai J., Ferrari M., Pompa P.P., Shen H. Lipopolyplex potentiates anti-tumor immunity of mRNA-based vaccination. Biomaterials. 2017;125:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichlmair A., Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., Perez J.L., Perez Marc G., Moreira E.D., Zerbini C., Bailey R., Swanson K.A., Roychoudhury S., Koury K., Li P., Kalina W.V., Cooper D., Frenck R.W., Jr., Hammitt L.L., Tureci O., Nell H., Schaefer A., Unal S., Tresnan D.B., Mather S., Dormitzer P.R., Sahin U., Jansen K.U., Gruber W.C., C4591001 Clinical Trial Group Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard C., Rejman J., De Haes W., Verrier B., Van Gulck E., Naessens T., De Smedt S., Bogaert P., Grooten J., Vanham G., De Koker S. Type I IFN counteracts the induction of antigen-specific immune responses by lipid-based delivery of mRNA vaccines. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:251–259. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch S., Jasny E., Schmidt K.E., Petsch B. New vaccine technologies to combat outbreak situations. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1963. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richner J.M., Himansu S., Dowd K.A., Butler S.L., Salazar V., Fox J.M., Julander J.G., Tang W.W., Shresta S., Pierson T.C., Ciaramella G., Diamond M.S. Modified mRNA vaccines protect against Zika virus infection. Cell. 2017;169:176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richner J.M., Himansu S., Dowd K.A., Butler S.L., Salazar V., Fox J.M., Julander J.G., Tang W.W., Shresta S., Pierson T.C., Ciaramella G., Diamond M.S. Modified mRNA vaccines protect against Zika virus infection. Cell. 2017;168(1114–1125) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rurik J.G., Tombácz I., Yadegari A., Méndez Fernández P.O., Shewale S.V., Li L., Kimura T., Soliman O.Y., Papp T.E., Tam Y.K., Mui B.L., Albelda S.M., Puré E., June C.H., Aghajanian H., Weissman D., Parhiz H., Epstein J.A. CAR T cells produced in vivo to treat cardiac injury. Science. 2022;375:91–96. doi: 10.1126/science.abm0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabnis S., Kumarasinghe E.S., Salerno T., Mihai C., Ketova T., Senn J.J., Lynn A., Bulychev A., McFadyen I., Chan J., Almarsson O., Stanton M.G., Benenato K.E. A novel amino lipid series for mRNA delivery: improved endosomal escape and sustained pharmacology and safety in non-human Primates. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U., Kariko K., Tureci O. mRNA-based therapeutics—developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:759–780. doi: 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U., Oehm P., Derhovanessian E., Jabulowsky R.A., Vormehr M., Gold M., Maurus D., Schwarck-Kokarakis D., Kuhn A.N., Omokoko T., Kranz L.M., Diken M., Kreiter S., Haas H., Attig S., Rae R., Cuk K., Kemmer-Bruck A., Breitkreuz A., Tolliver C., Caspar J., Quinkhardt J., Hebich L., Stein M., Hohberger A., Vogler I., Liebig I., Renken S., Sikorski J., Leierer M., Muller V., Mitzel-Rink H., Miederer M., Huber C., Grabbe S., Utikal J., Pinter A., Kaufmann R., Hassel J.C., Loquai C., Tureci O. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature. 2020;585:107–112. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U., Oehm P., Derhovanessian E., Jabulowsky R.A., Vormehr M., Gold M., Maurus D., Schwarck-Kokarakis D., Kuhn A.N., Omokoko T., Kranz L.M., Diken M., Kreiter S., Haas H., Attig S., Rae R., Cuk K., Kemmer-Brück A., Breitkreuz A., Tolliver C., Caspar J., Quinkhardt J., Hebich L., Stein M., Hohberger A., Vogler I., Liebig I., Renken S., Sikorski J., Leierer M., Müller V., Mitzel-Rink H., Miederer M., Huber C., Grabbe S., Utikal J., Pinter A., Kaufmann R., Hassel J.C., Loquai C., Türeci Ö. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature. 2020;585:107–112. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U., Muik A., Vogler I., Derhovanessian E., Kranz L.M., Vormehr M., Quandt J., Bidmon N., Ulges A., Baum A., Pascal K.E., Maurus D., Brachtendorf S., Lörks V., Sikorski J., Koch P., Hilker R., Becker D., Eller A.K., Grützner J., Tonigold M., Boesler C., Rosenbaum C., Heesen L., Kühnle M.C., Poran A., Dong J.Z., Luxemburger U., Kemmer-Brück A., Langer D., Bexon M., Bolte S., Palanche T., Schultz A., Baumann S., Mahiny A.J., Boros G., Reinholz J., Szabó G.T., Karikó K., Shi P.Y., Fontes-Garfias C., Perez J.L., Cutler M., Cooper D., Kyratsous C.A., Dormitzer P.R., Jansen K.U., Türeci Ö. BNT162b2 vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific T cells in humans. Nature. 2021;595:572–577. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher T.N., Schreiber R.D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian M., Papachristofilou A., Weiss C., Früh M., Cathomas R., Hilbe W., Wehler T., Rippin G., Koch S.D., Scheel B., Fotin-Mleczek M., Heidenreich R., Kallen K.J., Gnad-Vogt U., Zippelius A. Phase Ib study evaluating a self-adjuvanted mRNA cancer vaccine (RNActive®) combined with local radiation as consolidation and maintenance treatment for patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:748. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skold A.E., van Beek J.J., Sittig S.P., Bakdash G., Tel J., Schreibelt G., de Vries I.J. Protamine-stabilized RNA as an ex vivo stimulant of primary human dendritic cell subsets. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2015;64:1461–1473. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1746-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepinski J., Waddell C., Stolarski R., Darzynkiewicz E., Rhoads R.E. Synthesis and properties of mRNAs containing the novel "anti-reverse" cap analogs 7-methyl(3'-O-methyl)GpppG and 7-methyl (3'-deoxy)GpppG. RNA. 2001;7:1486–1495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Wan Y. Enhanced protein expression by internal ribosomal entry site-driven mRNA translation as a novel approach for in vitro loading of dendritic cells with antigens. Hum. Immunol. 2008;69:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauzin A., Nayrac M., Benlarbi M., Gong S.Y., Gasser R., Beaudoin-Bussieres G., Brassard N., Laumaea A., Vezina D., Prevost J., Anand S.P., Bourassa C., Gendron-Lepage G., Medjahed H., Goyette G., Niessl J., Tastet O., Gokool L., Morrisseau C., Arlotto P., Stamatatos L., McGuire A.T., Larochelle C., Uchil P., Lu M., Mothes W., De Serres G., Moreira S., Roger M., Richard J., Martel-Laferriere V., Duerr R., Tremblay C., Kaufmann D.E., Finzi A. A single dose of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BNT162b2 elicits Fc-mediated antibody effector functions and T cell responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(1137–1150) doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thess A., Grund S., Mui B.L., Hope M.J., Baumhof P., Fotin-Mleczek M., Schlake T. Sequence-engineered mRNA without chemical nucleoside modifications enables an effective protein therapy in large animals. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:1456–1464. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usme-Ciro J.A., Campillo-Pedroza N., Almazan F., Gallego-Gomez J.C. Cytoplasmic RNA viruses as potential vehicles for the delivery of therapeutic small RNAs. Virol. J. 2013;10:185. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A.B., Kanevsky I., Che Y., Swanson K.A., Muik A., Vormehr M., Kranz L.M., Walzer K.C., Hein S., Guler A., Loschko J., Maddur M.S., Ota-Setlik A., Tompkins K., Cole J., Lui B.G., Ziegenhals T., Plaschke A., Eisel D., Dany S.C., Fesser S., Erbar S., Bates F., Schneider D., Jesionek B., Sanger B., Wallisch A.K., Feuchter Y., Junginger H., Krumm S.A., Heinen A.P., Adams-Quack P., Schlereth J., Schille S., Kroner C., de la Caridad Guimil Garcia R., Hiller T., Fischer L., Sellers R.S., Choudhary S., Gonzalez O., Vascotto F., Gutman M.R., Fontenot J.A., Hall-Ursone S., Brasky K., Griffor M.C., Han S., Su A.A.H., Lees J.A., Nedoma N.L., Mashalidis E.H., Sahasrabudhe P.V., Tan C.Y., Pavliakova D., Singh G., Fontes-Garfias C., Pride M., Scully I.L., Ciolino T., Obregon J., Gazi M., Carrion R., Jr., Alfson K.J., Kalina W.V., Kaushal D., Shi P.Y., Klamp T., Rosenbaum C., Kuhn A.N., Tureci O., Dormitzer P.R., Jansen K.U., Sahin U. BNT162b vaccines protect rhesus macaques from SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;592:283–289. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03275-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weide B., Pascolo S., Scheel B., Derhovanessian E., Pflugfelder A., Eigentler T.K., Pawelec G., Hoerr I., Rammensee H.G., Garbe C. Direct injection of protamine-protected mRNA: results of a phase 1/2 vaccination trial in metastatic melanoma patients. J. Immunother. 2009;32:498–507. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman D., Pardi N., Muramatsu H., Kariko K. HPLC purification of in vitro transcribed long RNA. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;969:43–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-260-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L.J., Sariol C.A., Mattocks M.D., Wahala M.P.B.W., Yingsiwaphat V., Collier M.L., Whitley J., Mikkelsen R., Rodriguez I.V., Martinez M.I., de Silva A., Johnston R.E. An alphavirus vector-based tetravalent dengue vaccine induces a rapid and protective immune response in macaques that differs qualitatively from immunity induced by live virus infection. J. Virol. 2013;87:3409–3424. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02298-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J.A., Malone R.W., Williams P., Chong W., Acsadi G., Jani A., Felgner P.L. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science. 1990;247:1465–1468. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.Y., Ke T.Y., Liao W.Y., Chang N.Y. Regulation of coronaviral poly(A) tail length during infection. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C., Zhang C., Walker P.G., Dong Y. Formulation and delivery technologies for mRNA vaccines. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/82_2020_217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N.N., Li X.F., Deng Y.Q., Zhao H., Huang Y.J., Yang G., Huang W.J., Gao P., Zhou C., Zhang R.R., Guo Y., Sun S.H., Fan H., Zu S.L., Chen Q., He Q., Cao T.S., Huang X.Y., Qiu H.Y., Nie J.H., Jiang Y., Yan H.Y., Ye Q., Zhong X., Xue X.L., Zha Z.Y., Zhou D., Yang X., Wang Y.C., Ying B., Qin C.F. A thermostable mRNA vaccine against COVID-19. Cell. 2020;182(1271–1283) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., You X., Wang X., Cui L., Wang Z., Xu F., Li M., Yang Z., Liu J., Huang P., Kang Y., Wu J., Xia X. Delivery of mRNA vaccine with a lipid-like material potentiates antitumor efficacy through toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005191118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Tao W., Liu D., Wu J., Guo Z., Ji X., Bharwani Z., Zhao L., Zhao X., Farokhzad O.C., Shi J. Surface De-PEGylation controls nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery in vitro and in vivo. Theranostics. 2017;7:1990–2002. doi: 10.7150/thno.18136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]