Abstract

Background: Pulmonary hypertension is a rare complication of sarcoidosis. The pathogenesis of sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension is multifactorial, and patients with sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension can have variable treatment responses and prognoses. While selexipag (Nippon Shinyaku / Kyoto / Japan) was recently approved in Japan for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension, the risk of cerebral infarction has not been clearly reported. Case report: A 63-year-old Asian female with a diagnosis of ocular and cutaneous sarcoidosis developed shortness of breath and was referred to our department to rule out cardiac sarcoidosis. Swan–Ganz catheterization was performed, and she was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension and started on selexipag. A few days after starting treatment, she presented with hemiplegia and was diagnosed with cardiogenic cerebral embolism by using magnetic resonance imaging. As there was no evidence of pre-existing intracardiac thrombosis, we suspected unusual cerebral embolism. Echocardiography revealed a deep venous thrombus and a bubble study revealed a right-left shunt through a patent foramen ovale. Conclusions: The initiation of selexipag improved pulmonary blood flow and caused cerebral embolism, which was an unusual and unexpected event. This report highlights the importance of confirming the presence of patent foramen ovale and a deep venous thrombus before starting treatment for pulmonary hypertension.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension, Selexipag, Deep venous thrombus, Cerebral embolism, Patent foramen ovale

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown etiology, and complications of pulmonary hypertension are associated with a poor prognosis [1]. However, sarcoidosis has not been recognized as one of the diseases presumed to be strongly associated with pulmonary hypertension in the project for the treatment of specific diseases in Japan [2]. On the other hand, in Europe and the United States, sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension has been reported under the term “sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension” and is included in group 5 of the Nice classification system [3].

The pathogenesis of sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension is multifactorial and differs from that of classic pulmonary arterial hypertension; therefore, it is likely that patients with sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension have variable treatment responses and prognoses. Several treatment options for sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension have been described with variable treatment efficacy; these include long-term treatment with epoprostenol [4] and targeted therapies for primary pulmonary arterial hypertension, such as bosentan, sildenafil, iloprost inhalation, and intravenous epoprostenol, in patients with advanced disease [5].

Recently, selexipag, a prostacyclin derivative, was approved in Japan for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension in Nice groups 1 and 4. While prostacyclin preparations have antiplatelet effects and are associated with a risk of hemorrhagic events [6], the risk of cerebral infarction has not been clearly reported. Warfarin is also approved as supportive therapy for pulmonary hypertension in Japan, but there is a lack of evidence for anticoagulation, except in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic pulmonary thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Further, there is some hesitation because of the risk of bleeding events with the concomitant use of anticoagulation, especially in patients taking prostacyclin. Herein, we report a rare case of cerebral embolism after initiation of selexipag in a patient with no evidence of atrial fibrillation or intracardiac thrombus.

Case report

A 63-year-old woman, who was diagnosed with sarcoidosis involving the eyes and skin 5 years ago, presented to her local doctor with recent onset of shortness of breath and palpitations with light exertion. An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, and she was referred to our department with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis.

Laboratory investigations revealed mildly elevated N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels (729 pg/mL). The ECG showed sinus rhythm with multiple ventricular extrasystoles (Fig. 1), and echocardiography showed an elevated right atrial-right ventricular pressure gradient. Both echocardiography and computed tomography (CT) did not show any thrombus in the left ear, left atrium, or left ventricle (Fig. 2). Cardiac sarcoidosis was suspected, and the patient consented to myocardial biopsy and Swan–Ganz catheterization to confirm the diagnosis. However, on the day of the planned examination, the myocardial biopsy had to be interrupted due to frequent non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. Therefore, Swan–Ganz catheterization was performed, and the results were as follows: mean pulmonary artery wedge pressure = 5 mm Hg, mean pulmonary artery pressure = 44 mm Hg, and cardiac index = 2.2 L/(min.m2); therefore, she was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiac sarcoidosis was subsequently ruled out using fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (Fig. 3). Notably, Holter ECG showed no atrial fibrillation, and no pulmonary embolus or visible venous thrombus was noted on a thoracoabdominal CT (Fig. 2). Due to the high tricuspid regurgitation peak gradient (TRPG = 79.0 mm Hg, Fig. 4) and shortness of breath on minimal exertion, medical treatment for symptomatic sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension was indicated. Therefore, she was started on warfarin and the prostacyclin agonist selexipag and discharged. However, a few days after the start of medical treatment, the patient developed hemiplegia and was rushed to our hospital.

Fig. 1.

Twelve-lead electrocardiogram shows sinus rhythm and episodes of multiple ventricular tachycardia.

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan. The scan does not show any thrombus in the left ear, left atrium, or left ventricle. No thrombus suspicious for pulmonary artery thrombus and no contrast thrombus in major veins in the visible range are observed. On the other hand, right heart and multiple lymph node enlargements are observed.

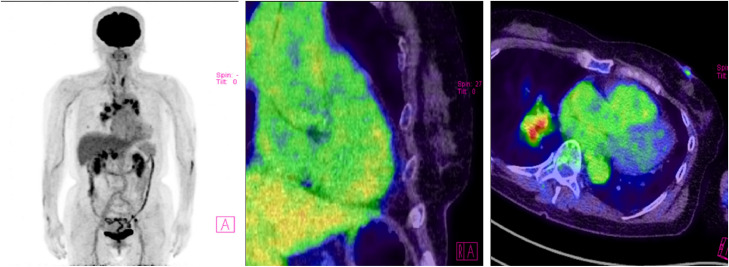

Fig. 3.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan. The scan shows accumulation in enlarged lymph nodes (red nodule) in the hilar region of the longitudinal lung section, but no abnormal accumulation in the myocardium. (Color figure is available online.)

Fig. 4.

Echocardiography shows normal left ventricular systolic function with elevated right ventricular pressure. TR-Peak Grad, tricuspid regurgitation peak gradient.

As the patient was taking warfarin and selexipag, we suspected cerebral hemorrhage; however, head CT showed no evidence of cerebral hemorrhage. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed acute infarction in the left frontal and parietal lobes, and the patient was diagnosed with cardiogenic cerebral embolism (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Head magnetic resonance imaging scan shows acute infarction in the left frontal and parietal lobes.

As it had already been confirmed that there was no atrial arrhythmia or intraventricular thrombus before the stroke event, a microbubble test was performed by lower-extremity venous echocardiography and transthoracic echocardiography to identify the embolic source. The results showed deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in the lower extremity (Fig. 6) and a patent foramen ovale (PFO) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Echocardiography of the lower extremities shows thrombus formation (white arrow) in the left soleus vein.

Fig. 7.

The microbubble (white arrows) test shows a right-left shunt possibly mediated by a patent foramen ovale.

Several differential diagnoses were considered. First, cerebral hemorrhage was suspected because of the patient's increased bleeding risk due to treatment with warfarin and selexipag, which was excluded via head CT. Therefore, we suspected cerebral infarction or neurosarcoidosis and performed brain MRI. The left anterior traffic artery and the branch of the middle cerebral artery were poorly visualized, and acute infarction was observed in the left frontal and parietal lobes. Contrast-enhanced MRI was originally thought to be necessary to differentiate neurosarcoidosis, but the preferred sites of neurosarcoidosis are the brain base, hypothalamus, and pituitary gland [7], and there was no evidence of lesions in the aforementioned regions. An atheroembolic mechanism was also considered as a possible cause of cerebral infarction, but magnetic resonance angiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and abdomen before the onset of cerebral infarction did not reveal any atherosclerotic lesions in the major vessels, leading to a final diagnosis of cardiogenic cerebral embolism.

The patient was started on treatment with tissue plasminogen activator and edaravone. However, there was little response to treatment, and she was left with significant functional impairment and muscle weakness in the left upper and lower limbs.

Given the lack of improvement in the patient's clinical condition, a multidisciplinary team meeting including cardiologists and neurosurgeons was held to determine the need for continuing treatment with warfarin and selexipag. Warfarin was initially started to prevent elevated pulmonary vascular pressure due to microthrombus formation in the pulmonary arteries, but was changed to edoxaban 15 mg/day for secondary prevention of cerebral embolism after the diagnosis of DVT and PFO. After starting selexipag, the patient's NT-proBNP level increased further (1761 pg/mL) and TRPG (62.4 mm Hg) on echocardiography decreased. Therefore, the patient remains at a high risk of future embolic and hemorrhagic events, and strict medication adherence and appropriate imaging are essential during hospitalization.

Discussion

This report describes a rare case of sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension that was medically treated and highlights several important points. First, the use of warfarin as anticoagulant therapy should be considered. Warfarin is indicated for the prevention of microthrombus formation in the pulmonary vasculature in patients with pulmonary hypertension, but there are no clear criteria for its use in Japan. In particular, although the Japanese guidelines for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension recommend oral anticoagulation (grade 2b) [8], this is not recommended in patients receiving concomitant treatment with pulmonary vasodilators such as epoprostenol [8]. In addition, warfarin tends to cause temporary hypercoagulability at the time of initiation, especially when the starting dose is 5 mg/day or higher [9]. Although the risk of DVT formation is increased in bedridden patients, the patient, in this case, was able to independently perform activities of daily living, and there was no evidence of venous thrombosis during the equilibrium phase of the CT of the chest and abdomen before the event. However, echocardiography of the lower extremities immediately after the onset of cerebral embolism revealed DVT, suggesting that the initial administration of warfarin may have had a pro-thrombotic effect.

The next most important factor is the role of selexipag. The patient in this case experienced a cerebral embolic event a few days after starting selexipag; therefore, it is highly likely that selexipag was implicated. Although the dose of the drug was only 0.2 mg twice a day, the improvement in TRPG after the administration of selexipag suggests that the drug may have had an effect. However, there have been few reports of cerebral infarction as an adverse effect of selexipag, and no study to date has suggested a causal relationship.

The new finding of cerebral embolism, in this case, suggests that the concomitant initiation of warfarin with pulmonary vasodilators in patients with pulmonary hypertension, including those with sarcoidosis, may temporarily embolize any pre-existing thrombus. In addition, in patients with incidental PFO, the initiation of pulmonary vasodilator treatment can increase venous return by reducing pulmonary vascular resistance and improving pulmonary blood flow. Furthermore, elevated right atrial pressure associated with pulmonary hypertension may exacerbate right-left shunting in patients with PFO, making them more prone to developing unusual embolisms. As a result, the newly formed mobile thrombus may lead to the development of any embolism, including cerebral embolism and possibly pulmonary embolism. Based on our experience, we strongly recommend that patients diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension should be screened for the presence of DVT or PFO before initiating treatment with anticoagulation therapy and pulmonary vasodilators. Pulmonary vasodilators improve pulmonary blood flow in patients with pulmonary hypertension and may increase the risk of embolism. As prostacyclin agents can cause bleeding due to their antiplatelet effect, care should be taken when they are used in combination with anticoagulant therapy. High doses of warfarin cause temporary hypercoagulation, which is a risk of thrombus formation at the start of treatment. Overall, the paradox of hemorrhage and embolism arises in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension, so it is important to rule out pre-existing PFO and DVT by echocardiography. The patient described in this case was relatively young and able to perform activities of daily living independently before the cerebral embolism. After treatment, her life changed drastically, and the burden on the patient and her family became considerable. We hope that this case will improve clinician awareness of this rare complication and help prevent similar cases in the future.

Human rights statements and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Naoya Ozawa, MD, for advice on diagnosis and treatment of sarcoidosis.

Patient consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2022.05.064.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Nagai S, Shigematsu M, Hamada K, Izumi T. Clinical courses and prognoses of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:293–298. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Japan Intractable Diseases Information Center. 2015. https://www.nanbyou.or.jp/entry/171. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- 3.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D34–D41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher KA, Serlin DM, Wilson KC, Walter RE, Berman JS, Farber HW. Sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: outcome with long-term epoprostenol treatment. Chest. 2006;130:1481–1488. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett CF, Bonura EJ, Nathan SD, Ahmad S, Shlobin OA, Osei K, et al. Treatment of sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: a two-center experience. Chest. 2009;135:1455–1461. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonneau G, Barst RJ, Galie N, Naeije R, Rich S, Bourge RC, et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:800–804. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns C, Scott P, Nissim J. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:909–917. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060080095022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidelines for Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension (Japanese Circulation Society 2017/Japanese Pulmonary Circulation and Pulmonary Hypertension Society 2017. https://www.j-circ.or.jp/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/JCS2017_fukuda_h.pdf. Accessed Nov 5, 2021.

- 9.Shepherd AM, Hewick DS, Moreland TA, Stevenson IH. Age as a determinant of sensitivity to warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;4:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1977.tb00719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.