Abstract

Aims/Purpose

To evaluate current day challenges and beliefs about breast cancer screening for Black women in two diverse northeast communities in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in women in the USA. Although Black women are less likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer, they suffer a higher mortality. Early detection of breast cancer can be accomplished through routine screening mammography, yet the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mammography screening barriers and perception in minority communities is uncertain.

Methods

Five focus group interviews were conducted as the first phase of a mixed method study across two heterogeneously diverse locations, Camden, New Jersey, and Brooklyn, New York.

Results

Thirty-three women participated in this study; sixteen women were recruited at the New Jersey location and seventeen at the New York location. Only two thirds of the women stated that they had received a mammogram within the last 2 years. The major themes were binary: I get screened or I do not get screened. Subthemes were categorized as patient related or system related.

Conclusions

Our findings on factors that affect breast cancer screening decisions during the COVID-19 era include barriers that are related to poverty and insurance status, as well as those that are related to medical mistrust and negative healthcare experiences. Community outreach efforts should concentrate on building trust, providing equitable digital access, and skillfully addressing breast health perceptions.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Breast disparities, Mammography screening, Cancer prevention, Breast health, Social determinants of health, COVID-19 pandemic, African American women, Black women, Focus groups, Breast cancer screening, Breast cancer screening barriers, COVID-19 era, Disparities

Introduction

In the USA, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related incidence and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in women. Although population related incidence rates are lower for Black women compared to White women, mortality is approximately 40% higher for Black women [1]. Reasons for these disparities are complex and have been attributed to advanced stage at diagnosis, higher likelihood of being diagnosed with a more aggressive phenotype such as triple-negative breast disease and earlier age at diagnosis [1]. There are also systemic and individual barriers that may contribute to the disparity seen such as poor access to quality healthcare systems and breast cancer screening as well as factors associated with social determinants of health [2, 3].

It is well-known that early detection of breast cancer can be accomplished through routine screening mammography. Despite this, studies have shown the use of mammography screening is lower in uninsured women and those with lower socioeconomic status [4–6]. In addition, breast cancer screening perceptions and anxieties may contribute to lower uptake of screening in minority populations.

In March of 2020, the SARS virus that causes the disease COVID-19 devastated the world. In the USA, northeastern metropolitan cities were the first to experience this devastation first-hand. During this time, local and federal agencies advised that non-elective procedures such as mammography screenings be postponed or canceled due to inadequate resources such as PPE and staffing [7]. Furthermore, guidelines from the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommended the breast cancer screenings be discontinued temporarily [8]. This led to unprecedented drops in breast cancer screenings [9]. While screening recommendations have since resumed across the USA, there is concern that resumption of screening for minority women will not immediately recover and that socioeconomic disadvantages should be considered [10].

Research shows that regardless of race and ethnicity, the lack of insurance and living in poverty are major barriers to breast cancer screening utilization [11–13]. Camden, New Jersey, is one of the poorest cities in the nation, with 36.4% of residents living in poverty in 2019 [14]. The 2016 Camden needs assessment noted that Camden County had lower mammography screening rates and women were diagnosed at a later stage and with a higher mortality than women in surrounding areas [15]. Brooklyn, New York, has the highest mortality due to breast cancer of all five boroughs of New York City [16].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate current day challenges to breast cancer screening for Black women in two diverse northeast communities in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. We explored women’s thoughts, feelings, experiences, and opinions towards mammography screening in the COVID-19 era. While hesitancy to get mammograms for Black women existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, we hypothesize that additional anxieties and barriers now exist. Understanding which factors may contribute to barriers and lack of adherence to screening for Black women in the COVID-19 era will be important for developing future community interventions to reach Black women. Additionally, understanding best practices for getting the word out to minority populations about the importance of mammography screening will better position community outreach leaders in narrowing the breast cancer disparities gap.

Methods

This study used focus group methodology as the first phase of a mixed method study across two locations, Camden, New Jersey, and Brooklyn, New York. Focus groups were chosen to not only develop an understanding of women’s thoughts, feelings, experiences, and opinions related to breast cancer screening in the COVID-19 era but to allow the researchers to compare women’s experiences at the two research sites. Two focus group meetings were planned for each location and the final focus group included participants from both locations.

Sampling

This study used a convenience sample and additional snowball recruitment to identify participants. Eligible women 40 years of age and older (in accordance with the American College of Radiology and the American Society of Breast Surgeons recommendations that average risk women begin screening at the age of 40 [17, 18]) were recruited to participate in these focus groups. Women who were English speaking and who identified as African American/Black, Afro-Caribbean, or Afro-Latina were recruited. Focus group-specific ads were placed in local newspapers and advertisements were placed on social media platforms. Advertisements directed interested women to a QR code-linked Qualtrics survey to assess eligibility, demographics, and contact information [19]. Additionally, a contact number was provided for interested participants who did not have digital access. Research team members than followed up with a call to eligible participants to further assess eligibility, interest, and availability. To expand diversity and representation within the sample, research team members partnered with local churches and other neighborhood organizations and used snowball recruiting methods. Knowledge and ability to use the Zoom virtual platform was assessed and a tutorial was provided when needed [20]. Online informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to participation. The women received $25 gift cards for their participation.

Data Collection

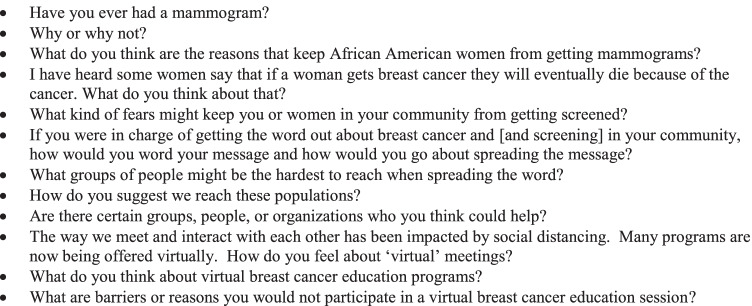

The focus groups were conducted by a team of moderators whose role was to facilitate the discussion and encourage all members to participate. The discussion guide consisted of open-ended questions relating to breast cancer screening with a specific focus on the experiences and perceptions of Black women. As this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, questions on access to health care and health education programs during the pandemic were included. The focus group interviews began by asking if participants had ever had a mammogram and proceeded to discuss the women’s perceptions of breast cancer screening and the breast cancer experience. See Fig. 1 for the list of interview questions.

Fig. 1.

Focus group questions

Five 60–90-min focus groups were conducted via the zoom virtual platform on December 2020 and January 2021 [20]. Online informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to participation, and participants completed a short demographic survey. The women received $25 gift cards for their participation. This study was reviewed and received institutional review board exemption.

Analysis

Demographic data were analyzed with Stata version 16. All interviews were audiotaped with permission and transcribed verbatim. The focus group transcripts were analyzed using a qualitative descriptive design. This design provides a less abstract, more closely held description of the data [21]. Considered the least theoretical method of qualitative research, the qualitative descriptive design provides a narrative in everyday terms of a participant’s experiences and perceptions. In this design, codes are not pre-conceived but are generated from the data [22]. The first step in the analysis of these transcripts was to identify important sections of text and attach labels to index these sections into coherent higher order codes [21]. BJD and ERR read the transcripts individually, identified codes, and then compared their choices and discussed their differences. After multiple reviews, the researchers agreed on a specific number of codes, which were then compiled into themes. While a number of relatively distinct themes were identified, they largely fit within a higher-level binary framework of decision-making on screening: I do get screened or I do not get screened. The COVID-19-related questions resulted in a theme which was consistent with the idea of getting the word out to the community about the need for breast cancer screening.

Results

Thirty-three women participated in this study; sixteen women were recruited at the New Jersey location and seventeen at the New York location. The average age was 58.4, with a range of 46 to 73 years of age. Twenty-eight of the women identified as African American or Black; four identified as Afro-Caribbean, and one woman identified as Afro-Latina. Twenty-five of the women were born in the USA; two were born in Jamaica, two in Guyana, and one each from Trinidad and St. Vincent, with two women declining to answer. The women who were born in other countries resided in the USA for an average of 38 years. At least 16 (45%) of women reported an income of less than US $49,000 which is below the poverty line. Two of the women reported being uninsured, eight women were Medicaid recipients, seven received Medicare, and two reported being insured via the military or Veterans Affairs. Fourteen women reported having private insurance, and the remainder declined to answer. Ninety percent of the women (n = 30) reported having ever had a mammogram and 65.6% (n = 21) reported having had a mammogram within the past 2 years. See Table 1 for demographics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n = 33)

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 40–50 | 9 | 27.3 |

| 51–60 | 11 | 33.3 |

| 61–75 | 13 | 39.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American/Black | 28 | 85.9 |

| Afro-Caribbean | 4 | 12.1 |

| Afro-Latina | 1 | 3.0 |

| Born in USAa | ||

| Yes | 25 | 76.0 |

| No | 6 | 18.0 |

| Declined | 2 | 6.0 |

| Marital statusa | ||

| Single | 12 | 37.5 |

| Married | 10 | 31.2 |

| Widowed | 2 | 6.3 |

| Separated/divorced | 7 | 21.9 |

| Domestic partner | 1 | 3.1 |

| Number of children | ||

| 0 | 6 | 18.2 |

| 1–3 | 25 | 75.7 |

| > 3 | 2 | 6.1 |

| Education | ||

| < High school | 1 | 3.0 |

| High school graduate | 4 | 12.1 |

| Some college | 9 | 27.3 |

| College graduate | 18 | 54.6 |

| Graduate school | 1 | 3.0 |

| Insurance status | ||

| Employer sponsored | 7 | 21.2 |

| Purchased on marketplace | 7 | 21.2 |

| Medicaid | 8 | 24.2 |

| Medicare | 7 | 21.2 |

| Military/VA | 2 | 6.1 |

| Uninsured | 2 | 6.1 |

| Incomea | ||

| > $10,000 | 2 | 6.5 |

| $10–24,999 | 5 | 16.1 |

| $25–49,000 | 9 | 29.0 |

| $50–99,999 | 12 | 38.7 |

| $100,000 and over | 3 | 9.7 |

| Mammogram ever | ||

| Yes | 30 | 90.9 |

| No | 3 | 9.1 |

| Mammogram in the past 2 years | ||

| Yes | 21 | 65.6 |

| No | 11 | 34.4 |

aData missing

Themes

The major themes noted could be defined by the binary: I get screened, or I do not get screened. Subthemes were categorized as patient related or system related. Caplan defined delays related to breast cancer diagnosis or treatment as patient-related (a delay in accessing medical care after a need is perceived or failure to keep appointments) and/or system-related (delays in getting an appointment, receiving diagnostic testing after an abnormal screening, or a delay in the initiation of treatment) [23]. In this study, we defined patient-related themes as those that influenced a participant’s decision-making about screening and system-related themes as a difficulty in a participant’s navigation or interaction with the health care system. The final theme was specifically related to communicating with Black women about the need for breast cancer screening and the pros and cons of virtual methods of communication. See Table 2 for the major themes, subthemes, and supporting quotes.

Table 2.

Participant quotes related to the themes

| Theme: I get screened |

|

Patient-related subthemes: I have the knowledge to take care of myself • If I do what I can, and I cope… I know I have to do it. So I do it. And that’s all I can do is try to prevent it and get tested early.” • “I would rather know – the sooner you are diagnosed the better you will do” • “because even you can have breast cancer and be treated and continue to live a happy and healthy life. So, because you are diagnosed with cancer, that doesn’t mean that you’re going to automatically die just like any other medical condition that you may have. Yeah, you can die from diabetes, you could die from a heart attack, but still you’re going to treat the condition. So, whatever you’re diagnosed with, you’re going to treat … this you’re unable to treat any longer.” |

|

My spirituality gives me strength • “we have to know how to turn that fear over to God. And I hope I don’t offend anybody by saying this but I’m a spiritual being. And we have to know how to relinquish that fear to God because … the Lord does not give us the spirit of fear, but he gives the spirit of peace, love and a sound mind and having a sound mind should push you to check yourself. We can’t let fear control us. And that’s what fear will do. It will control you to the point where you you lose sight of everything.” • “So I would say, use nutrition, use prayer. But God also works through the doctors. And he works through the medicine and ask him to direct you the way you should go. And then have faith. So it’s a combination, not just faith alone.” |

|

I have a family history so I must take extra care • “I have I have had several mammograms, I think basically started when I was in my either 40s or 50s. And I continue to have them on a yearly basis. And I think it’s very important that we do this, especially if you have cancer run in your family on both sides of the family. So it’s very important that I continue to have on even at my age right now, you know, I still have them.” • “I have had a mammogram. I got a mammogram because it’s a recommended and for me required screening. And because my sister is a breast cancer survivor.” |

| System-related subthemes: |

|

I was able to find access to compassionate care • “You know what, you know, I’ve had I have heard that, you know, they just push you up there and put you up there, you know, they have no compassion for mine. I’m blessed to say my radiologists are good.” • “I also had a technician that actually warmed it up because I had to do a sonogram so that I know how you feel when so you appreciate the fact that they think about those small things.” • “They even have warm hands because some of them have cold hands. You know, so they warm their hands up. Thank goodness |

| Theme: I do not get screened |

| Patient-related subthemes: |

|

Socioeconomics (no insurance, no money, no transportation, no time off from work, no primary care provider) • “And now the problem that I’m having now is I felt that it was too expensive.” • “…a fear of having no family support, they have young children, or they’re single mothers, or they’re just worried that they might have to stop from work, and they don’t have enough financial support. And they’re not gonna be able to pay the rent or the mortgage. And they just feel like they want to continue to work or to whenever but they don’t want to know.” • “The funds to get it done. You know, then it they’ll try to get it done. They don’t have the money so they put it off. No health insurance.” • “Um, well, I think one of the things that would keep women from getting a mammogram is a lack of insurance or thought that they need insurance to have one.” • “I had a mammogram but it’s been two years since I had a mammogram. And the reason being is I had to be referred out from my primary care doctor. And every time I when I go once a year for my physical and we always say he’s gonna make the referral for me to get a mammogram, but he never did.” |

|

Fear of the pain • “I am a big breasted person. And it’s very uncomfortable when you have to get it done. Just a procedure alone, just thinking about it.” • “it does hurt. It does hurt. And it’s archaic. I don’t understand why they can’t have a non invasive one. And we have the technology for it.” • “It’s just hearing. Those of us who have done it before, come and talk about the negative part of the mammogram like the the hurt or the pinch, and saying that they don’t have a medium size breast, it’s more painful. Things like that. That’s what I am hearing.” |

|

Fear of burdening your family • “What do you think about telling me a family is something that they would be afraid of? That you have breast cancer? That’s the number one fear.” • “My sister in law died from cancer, and she had it three times before. And on this fourth time, it was different. But she didn’t she refuse to face it. And her bills weren’t being paid. Her children suspected but didn’t know. So we started going to the hospital and to their appointments with her. And she started to let us in a little bit more and more, we ended up having to raise money for her. Because it got so bad that she was behind on everything. So for some people, they would rather not know. Because they know in their heart of hearts, that something is wrong.” |

|

Fear of hearing the diagnosis • “Me personally, I can’t really say why Black women don’t go in, get it done. When I am going to say is fear could be a major, you know, part of why they don’t get it done.” • “One of the reasons I have found over the years and talking to people and family members is fear. They have a fear of not wanting to know and, or they will either say, you know, I’m fine. There’s nothing wrong with me. And to me, that’s a form of denial. old saying was back in the day, what you don’t know will hurt won’t hurt you. But that’s not true. What you don’t know will kill you.” |

|

Fear of dying • “Well, it basically ends in death. Most women don’t know the extremes or anything about it. So just to know them, I have breast cancer, you know, they die. So it’s better off not knowing don’t want to know. Don’t care to know. that. nothing they can do is like maybe I don’t know the theory. But once they cut you open, you get this shortly after that.” • “Do they know what cancer is? There’s no cure for it. It’s coming in every shape form. all over your body. I mean, evidently they don’t know what it is and they can’t cure it is just killer.” • “Have you heard of any treatment for cancer? radiation and chemotherapy and whatever. But does it work? Bottom line just doesn’t work? I mean, there are some people that just don’t want to know, unfortunately.” • “I had another friend, something was coming out of her breast. And I asked her when she told me about it. I thought it was just like it had just happened. For three years this was happening. And she refused to go and get checked. So I asked her why didn’t you want to get check. She said, I know I have some things. She said if I’m going to die, I just want to die. I don’t want to know that I’m going to die. And that is a real fear.” |

|

Distrust of physicians • “Oh, my grandma said, man, no, doctors don’t know more than you. So it goes back to generations and traditions and just listening.” • “there’s a distrust of doctors and what they say, because of how they have treated us in the past. And they don’t want to deal with that. They don’t want to deal with the lack of empathy. They don’t want to deal with the fact that some of these doctors, they’re so they’re so beyond disrespectful. And they don’t ever listen to what you’re trying to say unless you force them to listen. It’s sometimes it’s like the struggle that they don’t need to handle.” • “That’s kind of you know, and yeah, I think to some extent, some, some of the medical professionals, they believe that they I that they, you know, they can give everybody a diagnosis.” |

|

Skepticism of mammography • “Radiation and, you know, all kinds of thoughts because I already had thyroid cancer. I’m like, I don’t need radiation every year. So I figure every three years would be good.” • “…sometimes people think that when you go there and they say, what is it radiation that you will get a lump after you actually go and get the test? That you know, it’s poison that they’re shooting into, or I don’t know the whole process |

|

Fatalism: I will take this to my grave • “She was like, Nah, I don’t want them touching me. I don’t know if something wrong with me. I just want this take it to the grave with me.” • “And for other people, they would rather not know, just in case something is wrong.” • “Sometimes people just live fearfully, okay, they, they rather live in fear than to face the facts and to live up to the facts.” • “It is. It is in God’s hands. So why even go get tested? Why would you want to? Like, honestly, why would you want to go get a mammogram? Or COVID test? Okay, cuz it’s in God’s hands.” |

|

If I have no symptoms and no family history so I don’t need to be screened. • “You can’t always live in that segment of I’m okay. You know, nobody in my family has it. I’m okay.” • “But I also know some of them just don’t have the reason to go see you know what’s going on because there’s no pain, no discharge no lumps no discoloration no reason.” • “Yes, I do have cousins and close friends that have had breast cancer. And it seems like it’s definitely in the lineage because several people within those families, so I imagine which is not my case, that if somebody close to me, Mom, aunt or somebody had breast cancer, it would change my attitude.” • “I do agree that if you have a family history of breast cancer, that would make you want to start getting mammograms even at an earlier age, the earliest age that they’re available to you.” |

|

I have too many family pressures, so my health is not my priority. • “… you know your family. And like she said, You’re the one that’s always running and taking care of them.” • Considering what was just mentioned in the last conversation that for some women, breast cancer is not a priority. And then for a lot of us we take care of so many other people that our overall health (is not a priority)” • “Yeah, it’s just that I never thought about getting it done. I got so much other stuff going on with me. Whereas though, getting a mammogram isn’t like one of my major priorities. I’m being on it.” • “When I speak to women, to black women, health is not a priority, that women are working really hard just to be alive, stay alive, keep alive, and take care of everybody else. So health generally, is not high up on the list. And so the fear of what will happen to other people, if I’m not here, not the fear of what’s going to happen to me, the fear of what will happen to other people, if I’m not here, to take care of X, Y, and Z.” |

| System-related subthemes: |

|

Having to deal with biased or inconsiderate staff. • “And the fact that when women No, I think when Black women go to the doctor they’re not given the kind of attention that our white counterparts see.” • “When you’re dealing with women’s issues, many of our things are our problems or situations get put on the backburner. And I’m glad of this forum because we need to put Black women’s issues on the forefront. I think the fact that we are the ones it was Black women that won that election with Joe Biden Black women, it would have been a no go and I think that people for the first time in a long time are starting to look at us as other than animals, other than problematic, and I think it’s our time.” • “Sometimes the people that are giving it aren’t as compassionate. I mean, they’re so used to doing it. They feel like we should just, you know, roll with the punches and do it and keep it moving.” • “And then you have the disrespect of your own kind. Because we like to treat each other that as African American, we treat each other very bad. We don’t have no love for each other. And when you walk into one of these centers, just the way they handle you or talk to you is enough to say I don’t need to do this. But if you have a chance or the opportunity to go to other facilities out to Central Brooklyn, it’s a total different experience, especially if you’re not dealing with your own kind. And I’ve experienced that a lot. And to be honest, I don’t do a lot of my health care in central Brooklyn.” |

| Theme: We need to get the word out |

| Subtheme But we just don’t talk about it |

|

• “But those are the detriments to women having mammograms and fear because there’s no there’s no information about it. And it’s not something that in our community we talk about.” • “Conversation is going to be one of the most difficult because they don’t know anybody. So it’s not real to them. It’s like, stuff being on TV. It’s not real.” • “Some people have knowledge that whether they are scientific or not, they can be from a family history of how the family thinks and feels and what it used to happen, I have not happened. And therefore, you know, people just make one of those excuses and don’t take advantage of opportunities that are given them.” • “Ladies, ladies, you know, we got to take care of ourselves, we know what’s going on. You know, we got to do Ladies, ladies, come on, we got to get ourselves together. You know, we got to do this Black girl magic, we need to take care of us. We don’t take care of us what’s gonna happen to them? And how they gonna function without us.” • “For this to be for it to become really what I keep calling a movement, and not just a month and not just a mammogram, but a movement around breast health and women’s health. And and for me the piece is also that women not feel that they have been that they are responsible for their own lack of or, or, you know that they are made to feel as if they are the criminals, right.” • “So what we have to do is all of these pieces that we are naming, whether you agree with the heart of it or not all of them, it’s going to take all the pieces to help women be empowered to see themselves as priority and their health as priority.” |

|

We need to get educated • “If I had the job, or the responsibility of getting a message out there to the women, I would have to school myself more on the process and on the problem. And I would have to really do some research and, you know, read up on why different types of cancer and why it is important for the African American women to be screened. Because, again, we we have families, children and husbands and mothers and, and, and fathers and grandparents that we don’t want to just leave here, just leave just like, you know, it doesn’t take you like that. But we, I think we should be at the point where we think more of our families, then we actually think of ourselves in if you put your family put God first in your family. Second, you would want to educate yourself on the progress of cancer or the different types of cancer or you would want to school yourself, educate yourself on what is going on.” |

|

Know your community and get the word out • “Every outlet that I can from social media, to coming through the block with a bullhorn free mammogram, make sure you put that word free mammogram, you know that get your insurance, you know, whatever you can someone else to suck up the cost, you know, because we don’t like to pay for a lot of things that we all know that’s true. You know, so free mammogram testing right here and then if you can get another truck next to it, let me see we can check you out with the high blood pressure you know how people sit down and get the high blood pressure test it see if you are a diabetic it’s a little like a mobile clinic.” • “I would ask the same questions like were asking here. What are your fears? What is your Why are you standoffish about it? You know, what would what do we need to do to show you how important it is to come and be screened and talk about it? So? I don’t know. I think I would, you know, ask them questions like, what’s your biggest fear? Why wouldn’t you come out and try to persuade them that way?” • “Of course, everybody goes goals and get the nails or hair done. So you beat the streets, you sometimes you have to beat the streets, even though what the COVID going on.” • “So, if I was in charge of trying to spread the word to Black women about screening, I would probably try to do community meetings at different community centers, pass out flyers, you know, even sometimes door to door Not that I might be safe anymore. But you know, if you like the mailman, you stick fliers in the door for women, or any family members to come out. That’s I would try to like get the community together and do community gatherings to talk about it and the importance of being screened for it.” • “You can do like the flyers and doctor’s offices, you can leave flyers there, because a lot of Black people do Black women to go to different doctors, you know how to leave the flowers on top of the counter, you know, corner stores, you know, word of mouth, organizations, different organizations, if you can find like an organization that you belong to, you can do a community fundraiser there, and just talk about the reasons why it’s important to get it done, especially for Black women at the age of 40.” • “I used to be a housing manager. And it was hard trying to get internet for some of the residents. So they will come to a community center. But right now with the pandemic threat, community centers is closed so they don’t have access to get the internet.” |

|

Use the church to bring people education • But not only that, like you said I’d hit him in the right place. Everybody goes to a church meeting • That’s when like you said you got to know your people know when they hit him. Some come out on Saturdays, the meeting and whatnot. That’s when we get them have trucks and stuff like that. • “We use the faith based groups, and we use the offices of the different… politicians who are in prayer we was there, and members of the organized groups, we get some people to go and hand out flyers.” • “My church was actually virtually ready from the beginning. So what happens is, we’re accessible virtually, like six days a week. And then on Sunday, we have announcements. So the last event that I did, which was in breast cancer, we made it but it was still health outreach, is that I set up a event on the virtual screen, telling you where you could get the health care how you could get it who was providing it. And that seems to work because we reach out to a large community.” |

I Do Get Screened

Patient-related subthemes discussed by women who do adhere to mammogram guidelines included having “the knowledge to take care of myself,” “my spirituality gives me strength,” and “I get screened because I have a family history.” Most of the participants reported having had at least one mammogram and this was consistent with the large number of participants demonstrating an understanding of the need for breast cancer screening. Many expressed the knowledge that an early diagnosis can improve outcome. One of the participants described her feelings this way, “If I do what I can, and I cope… I know I have to do it. So I do it. And that's all I can do is try to prevent it and get tested early.”

Another participant expressed the understanding of the benefit of an early diagnosis, “because even you can have breast cancer and be treated and continue to live a happy and healthy life. So, because you are diagnosed with cancer, that doesn't mean that you're going to automatically die just like any other medical condition that you may have. Yeah, you can die from diabetes, you could die from a heart attack, but still you're going to treat the condition. So, whatever you're diagnosed with, you're going to treat … this you're unable to treat any longer.”

Spirituality was described as a source of strength to encourage women to get screened. As one woman stated, “it's a combination, both like God created medicine. You know, man-made medicine. So you have to take, you know, the treatment also, but also have faith that with that treatment, you're going to be healed in God's word. Amen.”

A number of participants discussed having a family history of breast cancer and that this made them more inclined to be screened. One participant stated, “I have, I have had several mammograms, I think basically started when I was in my either 40s or 50s. And I continue to have them on a yearly basis. And I think it's very important that we do this, especially if you have cancer run in your family on both sides of the family.”

Although many of the participants understood that an annual screening is recommended, there were frequent comments about the pain of the procedure. A few participants talked about breast size as a factor in determining how painful the procedure would be, “the, the old style one where they smash you down, and a lot of us don't really want to have to go through that. Because it is painful. And some of us don't have big breasts. I'm not a big breasted woman. So it's even more difficult for me. So those are the things I've definitely heard that the pain of it.” Another participant, while understanding that the procedure is painful, still encourages her friends to get screened, “I'm big breasted also. And you have to hug the machine and lift your breasts up on top of the machine and they tell you don't move, they squeeze it, squeeze it, you got to hold it in. It deters people, but I tried to encourage people to go you know, especially women of color, and the ones over 40.”

A system-related subtheme that was a positive influence on women getting screened was the ability to find access to compassionate care. One woman described a positive experience thusly, “They even have warm hands because some of them have cold hands. You know, so they warm their hands up. Thank goodness.”

I Do Not Get Screened

There were many patient-related subthemes that lead women to avoid screening. They included socioeconomic factors, fear, fatalism, medical mistrust, and mammogram skepticism. Some of the patient-related factors such as “I don’t have a family history, so I don’t need to be screened” reflect a lack of knowledge about the need for cancer screening.

Each of the focus groups had at least one participant who was skeptical of mammograms or who shared beliefs which were not consistent with fact. One participant expressed her concern that mammograms can be harmful to your health, “personally, I don’t want to do it every year, because I don’t think that the mammogram itself, I believe the mammogram itself is what you call is dangerous, personally, and and and it puts you at risk of getting breast cancer, which is crazy.” Several participants shared stories about relatives who refused to acknowledge that they were not feeling well or had symptoms of breast cancer, until it was too late. One participant told the story of her mother’s death, “I recently lost my mother. And she had a stroke. But when … I got her to the hospital. They told me it’s not the stroke. That was the issue. They said she had breast cancer. And she did not share that with the family. She kept it in secret. Oh my goodness. And we found out on a I guess on a Tuesday. She passed away on a Thursday. She kept it a secret. She didn’t tell any anybody. Yes, she didn’t want to say the word either… she had six siblings, except for one all were cancer patients. So it’s something that runs in our family. And now I’m fearful. I’ve canceled two appointments already. But, you know, my mother was looking at her sibling because her sibling also was a person who did not get mammograms and she got breast cancer, and she said to her, I’m going to, I’m going to die. So my mom took the same type of attitude. She just she kept this secret. You know, it wasn’t anything that we could do. There was no time left to fix it. But it was all because of fear. Her parents, they also had cancer. So she was in fear. To go to the doctor and to get checked and that’s why she kept it a secret because she knew that we would try to intervene and take her to a doctor. And now we can’t fix it.” Even after describing this experience the participant explained that she herself had not been screened; had canceled two appointments. She acknowledged the need for a mammogram and also expressed the fear of being given a cancer diagnosis.

Some of the fears described by participants as reasons to not get screened included fear of being diagnosed, fear of dying, and fear of having to tell your family that you have cancer. Indeed, family was cited as both a reason to get screened (“it runs in my family, “my family depends on me”) and a reason not to get screened (“No one in my family has had breast cancer, so I don’t need to get screened, I don’t want to burden my family because of my health, or I’m too busy taking care of my family to take care of myself”).

A few participants were convinced that breast cancer was a death sentence. Comparing breast cancer screening to taking a COVID-19 test one participant explained, “that again, it all boils down to a lot of people don’t want to look into COVID test, because there’s no cure for it? Well, you know, you got it, you know, you’re gonna die. Like who wants to know, they’re going to die in X amount of time. That’s the bottom line. Knowing in just a matter of time that you have something, there’s no cure for, and it’s a matter of time. So why would you want to do that?”

Some participants mentioned the fact that in their social groups they only discuss negative aspects of mammography, such as the pain of the procedure, and not the positive factors, such as early diagnosis, that would empower more women to get screened and adhere to a regular screening schedule. A small number of participants expressed the belief that if you do not have symptoms you do not need to be screened. One participant explained, “but I also know some of them just don’t have the reason to go see you know what’s going on because there’s no pain, no discharge, no lumps, no discoloration, no reason.”

Distrust of physicians and being treated by biased or inconsiderate providers or technicians was a complaint expressed by a small number of participants. One participant expressed her distrust this way, “And after they and I thought they were finished, they came back and kept taking pictures. And then they were taking pictures again, it was like, Hey, this is a human being, you know, what are you seeing that’s different that you didn’t see the first time. And that was a real turnoff for me. And I have not gone back to that place since then. And, you know, and and so, um, you know, I think in a sense, some people want you to, to leave the office with breast cancer. That’s kind of you know, and yeah, I think to some extent, some, some of the medical professionals, they believe that they I that they, you know, they can give everybody a diagnosis.” Another participant explained, “You know, but I think that people get what they expect. I think you get whatever you settle for.”

Getting the Word Out

While many of the focus group participants appeared to be knowledgeable about the need for breast cancer screening, they did have concerns about members of the community who may choose not to get screened. One participant expressed her concerns this way, “And … for me the piece is also that women not feel that they have been that they are responsible for their own lack of or, or, you know that they are made to feel as if they are the criminals, right. And just as has been discovered with COVID, which we all knew everyone that’s Black and knew this, they’re just discovering it with COVID, that Blacks are dying twice as much twice the rates of white, we always knew that Black people in terms of their health, (are) behind the eight ball.”

Participants talked about the need to empower Black women and educate them about breast cancer, but they were realistic in assessing that for Black women their own health is often not a priority. One participant stated, “So there is a system that has existed that has created circumstances around women’s health. So what we have to do is all of these pieces that we are naming, whether you agree with the heart of it or not all of them, it’s going to take all the pieces to help women be empowered to see themselves as priority and their health as priority.”

A number of participants talked about using church as a means to reach out to women in the community, while acknowledging the fact that now many churches are not meeting in person and so any educational program would have to be provided via the internet. The participants were asked if they thought that virtual educational programs would be effective, but some brought up the fact that many women in their communities, likely the women most in need of education and encouragement, do not have access to the internet or may only be able to use their telephones to participate in educational programs. One participant explained, “A lot of the individuals that I work with in my community, they pretty much don’t have that technology to do online …to listen and listen, a lot of them may be able to listen during phone calls, but not far as, you know, online.”

While one or two participants explained that they do discuss their health with their friends or relatives, a larger number expressed the concern that women were not sharing their experiences with breast cancer. One participant compared breast cancer with COVID-19 by saying, “understand that there’s a whole segment of women that just like the COVID wasn’t real for people, this is just not real to them. They don’t know anybody who’s had cancer, breast cancer, they don’t know anybody that had a mammogram, they don’t know anybody. And if you know us as a people, and we don’t know somebody that went through something, and we’re not touching it, like we don’t know, somebody that will take this vaccine, we’re not taking it. And you and they keep pushing it out there with all the people saying, Go take it, go take it, but you know, if we don’t know…we’re not gonna go take it.” Another participant stated, “but those are the detriments to women having mammograms and fear because there’s no there’s no information about it. And it’s not something that in our community we talk about. Conversation is going to be one of the most difficult because they don’t know anybody. So it’s not real to them. It’s like, stuff being on TV. It’s not real.”

The primary system-related subtheme discouraging mammography was experiences with biased or inconsiderate staff at screening sites. One woman expressed her negative experience this way, “And the fact that when women No, I think when Black women go to the doctor they’re not given the kind of attention that our white counterparts see.”

There were few differences noted in the transcripts based on a participant’s area of residence. Two of the participants did complain of an inability to find acceptable care near their homes in New York, whereas this did not appear to be a concern in the New Jersey participants. No other observations or concerns were expressed that would differentiate a participant based on her residence.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to better understand the factors that influence breast cancer screening among Black women in two locations: Camden, NJ, a low income primarily African American/Black and Latinx city in southern New Jersey, and Brooklyn, NY, a demographically heterogeneous borough of New York City. The initial goal of this study was to recruit low-income women who were uninsured or Medicaid recipients for the focus groups; however, due to the COVID-19 lockdown, difficulties in recruiting this essentially hard to reach population were found. The resultant focus groups were a combination of low income, uninsured women, and Medicaid recipients and women with higher socioeconomic status. Fourteen of the thirty-three women reported having private insurance, either through their employment or purchased on the Affordable Care Act Marketplace, and more than half of the women reported being college graduates. While women did discuss inability to access screening services related to lack of insurance or financial insecurity, the women with insurance in this sample did not describe being insured as a facilitating factor for mammography. No differences were noted by location in the themes identified through the focus group discussions; however, one participant in the Brooklyn sample did discuss her perception of inconsiderate care received from health care workers in Brooklyn. This participant would rather go outside of Brooklyn to receive services due to the disrespect she reported.

Just over 90% of the women reported having ever had a mammogram, while a much lower 65.6% of the women stated that they had received a mammogram within the last 2 years. This rate is lower than the 84.5% reported by the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Data [24]. While socioeconomic status did not appear to reflect a difference in mammogram utilization in this study, in general, socioeconomic, structural, and cultural factors have been found to be barriers towards mammogram utilization in Black women [25] and any effort to increase screening utilization should be cognizant of these barriers. Additionally, the impact of COVID-19 on access cannot be understated.

The primary facilitators encouraging screening in this population included understanding the importance of screening, positive family history, spirituality, and having faith in the tools God has given them (medicine). Brandzel and colleagues found that Latinas and Black women who had faith in the benefits of the screening were more likely to get screened [2]. In this study, several women who reported having mammograms discussed the importance of early detection and understanding that outcomes improve when breast cancer is diagnosed early. As well, some noted the importance of empowering Black women about breast cancer through education.

Conversely, confusion about screening intervals and not having a clear understanding of the benefits serves as deterrents to screening [24, 25]. In this study, several participants expressed the understanding that if they had no signs or symptoms of breast cancer, then they did not need to be screened. Orji and colleagues, in an integrative review of 23 studies consisting almost entirely of African American/Black women, found that the lack of a perceived need for mammography, based on the belief that their breasts were healthy, was a major disincentive for women to undergo mammography [25].

Both family history and religiosity led to follow-through on mammography screening in our focus group members. Some group members discussed seeing family members diagnosed with cancer leading them to get screened while others pointed out that faith gave them strength to move on with their screening and trust man-made treatments. Similarly, the literature notes that a family history can positively influence mammography screening, especially when there is strong belief [25–28] and that women who attend religious services are more likely to have had a mammogram or other screenings [29]. Although our group did not equate faith with screening evasion, other studies have shown that having religious beliefs and faith in God can be a barrier to screening [30].

Despite the factors that can encourage women to perceive the need for screening, barriers were more frequently noted, and these were primarily patient related and included fears, fatalistic thoughts, and distrust. Fear included fear of dying, fear of the diagnosis, and fear of sharing the news with family. There were also fatalistic thoughts and negative social talk regarding mammography. These types of barriers have been previously identified in the literature and are often related to social determinants of care [3].

Some studies of Black women specifically have found additional barriers. Jones et al.’s review of the literature noted that fear of an abnormal finding and cancer treatments led to delays in care among Black women [31]. As well, for Black women, fear of the results/diagnosis led to decreased interest in obtaining mammography [28, 32]. Furthermore, Passmore et al. found that for uninsured Black women, family responsibilities led to secrecy and prevented them from sharing their diagnosis with family [28]. These fears are widely acknowledged in the literature and by the focus group participants as common reasons for avoiding screenings.

Fatalism continues to be a barrier to care among Black women [28, 33, 34]. The belief that mammography and positive findings are equated to death may prevent a number of Black women from being screened [30, 35]. A few focus group members stated that breast cancer was incurable and a death sentence.

Pain was a concern for both the focus group participants who do or do not get screened. The pain could have been personally experienced during a previous mammography screening or shared by other persons around them. Though the “I do get screened” group dealt with it and still followed through with screening, the “I do not get screened” group saw it as a reason to avoid screening. Several previous studies have pointed out that pain is a barrier for screening among Black women and a reason to avoid mammography [36–38]. The conversations about negative experiences of mammography among Black women may be especially influential upon other women’s avoidance of screening, especially in those who are mammography-naive [34, 36, 37]. Developing future messaging related to this barrier to care may be helpful in educating Black women while debunking some of the widely held myths that lead to avoidance of screening.

Distrust of mammography and distrust of the healthcare team and system were of concern and may be related to the barriers identified as system related, specifically the contact with biased and disrespectful healthcare providers. Prather and colleagues found that discriminatory healthcare practices negatively influence the quality and types of healthcare provided to Black women [39]. Distrust of the health care system as well as concerns regarding discrimination has been found to be a barrier to screening [26, 40]. Discrimination is especially perceived by Black women compared to other ethnic groups, leading to increased screening barriers [41]. A few of the focus group participants voiced concerns about distrust and biases related to the physicians or technicians who cared for them. Kim et al. noted that Black women, women who do not have trust in the healthcare system, and those who live in poverty less often report or acknowledge barriers to mammography screening; thus, they may be less likely to receive support such as navigation [42]. This is quite important as several studies have shown that patient navigation is critical to increasing screening rates in minority communities [43–46]. As we continue to assess barriers to care for Black women, it is just as important to educate them about resources, such as navigation services, regardless of whether or not they have requested these services. Additionally, building systems that are trust-worthy is a critical first step in addressing this system-based barrier.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented many unforeseen challenges. Using data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, Sprague et al. looked at trends utilizing screening and diagnostic mammography during the COVID-19 pandemic and noted racial/ethnic differences in rebound mammography use [47]. Implementing community sensitive strategies to get the word out about the importance of breast screening in such circumstances would be important. The COVID-19 pandemic magnified the existence of the digital divide; not all technological advances are equally accessible to minority communities. Developing outreach that incorporates telephone engagement as well as advocating for access to broad band service and advanced technology will be an important first step in getting the word out.

Strengths and Limitations

As in all qualitative research, limitations in generalizability must be accepted. While the focus groups were united in their self-identification as Black, not all of these women reported low incomes, low education levels, or a lack of insurance. Given the fact that the researchers were recruiting and conducting this study during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely that the reliance on online communication had a negative impact on the broader representation of the two communities in the focus groups, thus requiring the researchers to include women who did not report low incomes or the lack of insurance. Despite this, the barriers discussed in the focus groups were similar to those found in studies of low-income and uninsured Black women. The strengths of this study, however, outweigh the limitations by explicating the lived experience of Black women residing in two urban communities in the Northeast. The focus group discussions from the two different sites resulted in similar findings, which lend credence to the assumption that the participants of this study were able to give voice to the barriers that prevent Black women from accessing preventive care and cancer screening.

Conclusion

Despite numerous studies on why Black women hesitate to obtain screening mammography, there are still research gaps surrounding this issue. One study suggested the importance of specifically focusing future research on women who are not getting screened in order to better understand this question [48], but this group is hard to reach and perhaps less likely to have access to research. Our findings on factors that affect breast cancer screening decisions point to both barriers and facilitators that are not solely related to poverty and insurance. Community outreach efforts should concentrate on building trust, providing equitable digital access, and skillfully addressing breast health perceptions while incorporating strategies to address fear and fatalism.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by VJB, FA, and PW. Analysis was performed by BJ-D’E and ER-R. The first draft of the manuscript was written by VJB, BJ-D’E, and ER-R and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society and Pfizer (Grant number 203239-02). Vivian J. Bea and Evelyn Robles-Rodriguez has received research support from the American Cancer Society and Pfizer.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Western IRB committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required and granted exemption for this study.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

N/A.

Conflict of Interests

Vivian J. Bea has received funding from the American Cancer Society and Pfizer. Bonnie Jerome-D’Emilia, Francesse Antoine, Plyshett Wiggins, and Diane Hyman declare no competing interests. Evelyn Robles-Rodriguez receives funding from the American Cancer Society and Pfizer.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Ahmedin J. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman LA. Breast cancer disparities: socioeconomic factors versus biology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(10):2869–2875. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5977-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coughlin SS. Social determinants of breast cancer risk, stage, and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177(3):537–548. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vang S, Margolies LR, Jandorf L. Peer reviewed: mobile mammography participation among medically underserved women: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ahmed Ahmed T, et al. Racial disparities in screening mammography in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(2):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keshinro Ajaratu, et al. The impact of primary care providers on patient screening mammography and initial presentation in an underserved clinical setting. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(3):692–697. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (2020). CMS releases recommendations on adult elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures during COVID-19 response. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental. Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

- 8.American College of Radiology. States with elective medical procedures guidance in effect. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/COVID19/May-18_States-With-Elective-Medical-Procedures-Guidance-in-Effect.pdf. Accessed 20 Nov 2020.

- 9.Norbash Alexander M, et al. Early-Stage radiology volume effects and considerations with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: adaptations, risks, and lessons learned. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(9):1086–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balogun Onyinye D, Bea Vivian J, Phillips Erica. Disparities in cancer outcomes due to COVID-19—a tale of 2 cities. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(10):1531–1532. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haji-Jama S, et al. Disparities among minority women with breast cancer living in impoverished areas of California. 2016; 157-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hsu Christine D, et al. Breast cancer stage variation and survival in association with insurance status and sociodemographic factors in US women 18 to 64 years old. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3125–3131. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maskarinec Gertraud, et al. Ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: status and determinants. Women’s health. 2011;7(6):677–687. doi: 10.2217/whe.11.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Census Bureau (2019). Data USA: Camden, NJ. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/camden-nj/#economy. Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

- 15.Baker T (2016). The South Jersey Health Partnership 2016 Community Health Needs Assessment. https://www.cooperhealth.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/CHNA-2016.pdf. Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

- 16.Hunt BR, et al. Increasing black: White disparities in breast cancer mortality in the 50 largest cities in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;38(2):118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monticciolo DL, et al. Breast cancer screening for average-risk women: recommendations from the ACR commission on breast imaging. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(9):1137–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The American Society of Breast Surgeons (2019). Position statement on screening mammography. www.breastsurgeons.org/docs/statements/PositionStatement-on-Screening-Mammography.pdf.. Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

- 19.Qualtrics. 2005. Provo, Utah: Qualtrics.

- 20.Zoom. 2016. Zoom Video Communications Inc.

- 21.Sandelowski Margarete. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert Vickie A, Lambert Clinton E. Qualitative descriptive research: an acceptable design. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2012;16(4):255–256. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caplan Lee. Delay in breast cancer: implications for stage at diagnosis and survival. Front Public Health. 2014;2:87. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control. 202. State Cancer Profiles. https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/risk/index.php?topic=women&risk=v05&race=02&type=risk&sortVariableName=default&sortOrder=default#results. Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

- 25.Orji CC, et al. Factors that influence mammography use for breast cancer screening among African American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Brandzel Susan, et al. Latina and black/African American women’s perspectives on cancer screening and cancer screening reminders. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(5):1000–1008. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ackerson K, Preston SD. A decision theory perspective on why women do or do not decide to have cancer screening: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(6):1130–1140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passmore SR, et al. Message received: African American women and breast cancer screening. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(5):726–733. doi: 10.1177/1524839917696714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leyva B, et al. Is religiosity associated with cancer screening? Results from a national survey. J Relig Health. 2015;54(3):998–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9843-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swinney JE, Dobal MT. Older African American women’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors about breast cancer. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2011;4(1):9–18. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20101207-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.EL Jones C, et al. A systematic review of barriers to early presentation and diagnosis with breast cancer among black women. BMJ open. 2014;4(2):e004076. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed NU, et al. Clustering very low-income, insured women’s mammography screening barriers into potentially functional subgroups. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22(3):e259–e266. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zollinger TW, et al. Effects of personal characteristics on African-American women’s beliefs about breast cancer. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24(6):371–377. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07031727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peek ME, Sayad JV, Markwardt R. Fear, fatalism and breast cancer screening in low-income African-American women: the role of clinicians and the health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1847–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0756-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gullatte MM, et al. Religiosity, spirituality, and cancer fatalism beliefs on delay in breast cancer diagnosis in African American women. J Relig Health. 2010;49(1):62–72. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corrarino JE. Barriers to mammography use for Black women. J Nurse Pract. 2015;11(8):790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Highfield L, et al. Grounding evidence-based approaches to cancer prevention in the community: a case study of mammography barriers in underserved African American women. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(6):904–914. doi: 10.1177/1524839914534685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schueler KM, Chu PW, Smith-Bindman R. Factors associated with mammography utilization: a systematic quantitative review of the literature. J Women’s Health. 2008;17(9):1477–1498. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prather C, et al. Racism, African American women, and their sexual and reproductive health: a review of historical and contemporary evidence and implications for health equity. Health equity. 2018;2(1):249–259. doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shelton RC, et al. An investigation into the social context of low-income, urban Black and Latina women: implications for adherence to recommended health behaviors. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(5):471–481. doi: 10.1177/1090198110382502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobs EA, et al. Perceived discrimination is associated with reduced breast and cervical cancer screening: the study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN) J Women’s Health. 2014;23(2):138–145. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SJ, et al. Gendered and racialized social expectations, barriers, and delayed breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2018;124(22):4350–4357. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun KL, et al. Reducing cancer screening disparities in Medicare beneficiaries through cancer patient navigation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):365–370. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn SF, et al. Cervical and breast cancer screening after CARES: a community program for immigrant and marginalized women. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jandorf L, et al. Increasing cancer screening for Latinas: examining the impact of health messages and navigation in a cluster-randomized study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1(2):85–100. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0014-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Natale-Pereira A, et al. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3541–3550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sprague BL, et al. Changes in mammography utilization by women’s characteristics during the first 5 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wells AA, et al. Perspectives of low-income African-American women non-adherent to mammography screening: the importance of information, behavioral skills, and motivation. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32(2):328–334. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0947-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]