Abstract

Neurorecovery from locomotor training is well established in human spinal cord injury (SCI). However, neurorecovery resulting from combined interventions has not been widely studied. In this randomized clinical trial, we established the tibialis anterior (TA) flexion reflex modulation pattern when transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the primary motor cortex was paired with transcutaneous spinal cord (transspinal) stimulation over the thoracolumbar region during assisted step training. Single pulses of TMS were delivered either before (TMS-transspinal) or after (transspinal-TMS) transspinal stimulation during the stance phase of the less impaired leg. Eight individuals with chronic incomplete or complete SCI received at least 20 sessions of paired stimulation during assisted step training. Each session consisted of 240 paired stimuli delivered over 10-min blocks for 1 h during robotic-assisted step training with the Lokomat6 Pro®. Body weight support, leg guidance force and treadmill speed were adjusted based on each participant’s ability to step without knee buckling or toe dragging. Both the early and late TA flexion reflex remained unaltered after TMS-transspinal and locomotor training. In contrast, the early and late TA flexion reflexes were significantly depressed during stepping after transspinal-TMS and locomotor training. Reflex changes occurred at similar slopes and intercepts before and after training. Our findings support that targeted brain and spinal cord stimulation coupled with locomotor training reorganizes the function of flexion reflex pathways, which are a part of locomotor networks, in humans with varying levels of sensorimotor function after SCI.

Keywords: Flexion reflex, Locomotor training, Paired-associative stimulation, Rehabilitation, Spinal cord injury, Transspinal stimulation, TMS

Introduction

Locomotor training is the current standard of rehabilitation care to repair neuronal dysfunction after spinal cord injury (SCI) and ameliorate walking impairments through activity-dependent reorganization of neuronal circuits (Barbeau 2003; Edgerton et al. 2004; Knikou 2010a; Rossignol and Frigon 2011; Smith and Knikou 2016). The tibialis anterior (TA) polysynaptic spinal flexion reflex usually manifests with a short latency reflex activity that partly aids foot clearance and swing phase during stepping in healthy humans (Zehr et al. 1997, 1998). However, at the chronic stage of SCI the early TA flexion reflex is either abolished or severely diminished while long-lasting responses appear with their behavior underlying pathological changes of locomotor activity (Roby-Brami and Bussel 1987; Knikou and Conway 2005; Dietz et al. 2009). The long-lasting flexion reflex in human SCI has a similar neuronal organization to that reported in acute spinal cats treated with L-DOPA, a norepinephrine precursor (Andán et al. 1966; Jankowska et al. 1967a, b; Roby-Brami and Bussel 1987, 1990, 1992), representing partly the flexor burst generator of locomotion (Jankowska et al. 1967a; Schomburg et al. 1998). Locomotor training reorganizes the behavior of the polysynaptic responses with increases in short-latency and decreases in long-latency flexion reflex activity being reported (Smith et al. 2014).

Activity-dependent neuroplasticity along the axis of the nervous system is also possible with repeated paired associative stimulation (PAS; Stefan et al. 2000; Taylor and Martin 2009; Cortes et al. 2011; Bunday and Perez 2012). Although procedures for PAS are different, PAS-induced plasticity occurs by similar mechanisms as spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) which is based on the Hebbian principle of associative plasticity (Hebb 1949; Markram et al. 1997; Stefan et al. 2000, 2002; Song et al. 2000). Specifically, modification of the sign and degree of synaptic function arises from relative timing between paired pre- and post-synaptic action potentials (for review, see: Dan and Poo 2006; Markram et al. 2011). Potentiation, or strengthening, of synapses occurs when presynaptic action potential precedes postsynaptic firing by no more than 50 ms and depression, or weakening, of synapses occurs upon reverse order of the two action potentials (Buonomano and Merzenich 1998; Sjöström et al. 2008; Müller-Dahlhaus et al. 2010; Markram et al. 2011). In humans, PAS and motor-training-induced plasticity likely share the same synapses or involve interactions of similar neuronal circuits (Ziemann et al. 2001; Rosenkranz et al. 2007), strongly supporting a functional translation.

Paired transcranial magnetic (TMS) and peripheral nerve stimulation produce changes in corticospinal and motoneuronal excitability in conjunction with improvements in motor function in healthy humans and individuals with SCI (Meunier et al. 2007; Jayaram and Stinear 2007; Taylor and Martin 2009; Lamy et al. 2010; Bunday and Perez 2012; Jo and Perez 2020). Based on task-dependent neuromodulation and neurorecovery, greater neuroplastic changes and functional benefits are expected to occur when PAS paradigms are delivered during motor activity compared to when stimuli are delivered at rest after SCI (McPherson et al. 2015; Bunday et al. 2018; Jo and Perez 2020). Considering PAS enhancement during motor activity and the changes in excitability of neurons, afferents and axons, and corticospinal neuronal circuits during locomotor activity (Knikou 2010b; Côté et al. 2018), PAS coupled with locomotor training could be expected to be superior compared to PAS being delivered during a non-functional resting state.

In traditional PAS paradigms, peripheral nerve stimulation, one of the two paired stimuli, modulates synapses for a specific spinal segment and muscle innervated by the target motoneurons. Transcutaneous spinal cord (transspinal) stimulation on the other hand, depolarizes bilateral posterior-root afferents simultaneously and transsynaptically activates motoneurons over multiple spinal segments (Minassian et al. 2007; Courtine et al. 2007; Knikou 2013a; Murray and Knikou 2019a). When pairing single pulses of TMS and transspinal stimulation, the motor and transspinal evoked potentials (MEPs, TEPs) summate in the surface EMG when transspinal stimulation is delivered from 8 to 25 ms after TMS (Roy et al. 2014; Knikou 2014), suggesting facilitatory neural interactions between neural circuits mediating MEPs and TEP sat the spinal level. Furthermore, a single session of repeated TMS delivered after transspinal stimulation (transspinal-TMS) in a PAS paradigm increases corticospinal excitability with concomitant decreases of motor threshold and H-reflex low-frequency-mediated homosynaptic depression (Dixon et al. 2016). In contrast, repeated TMS delivered before transspinal stimulation (TMS-transspinal) decreases corticospinal excitability and reduces post-activation depression in healthy humans, while both protocols affect the excitation threshold of Ia afferents and motor axons (Dixon et al. 2016). Additionally, transspinal stimulation alone during locomotor training has depressive effects while restoring TA flexion reflex phase-dependent modulation (Zaaya et al. 2021). These results strongly support the hypothesis that non-invasive targeted brain and spinal cord paired stimulation during assisted step training will affect the behavior of the TA flexion reflex in people with SCI. We further hypothesized that TMS (presynaptic) delivered before transspinal (postsynaptic) results in TA flexion reflex facilitation, and reflex depression when TMS is delivered after transspinal. In this study, we report changes in TA flexion reflex excitability for a group of participants where reorganization of soleus H-reflex excitability after paired TMS and transspinal stimulation delivered during the stance phase of assisted stepping was postulated (Pulverenti et al. 2021).

Materials and methods

Participants

Eight participants with SCI with a mean age of 45.81 ± 15.47 years, height 175.54 ± 8.8 cm, and weight 79.81 ± 17.21 kg (mean ± SD) participated in the study. Inclusion criteria to the clinical trial were the following: age 18–75 years, chronic (> 12 months) C2-T11 SCI, and presence of Achilles tendon reflexes. Exclusion criteria to the clinical trial were the following: presence of supraspinal lesions, neuropathies of the peripheral nervous system, presence of pressure sores, presence of medical implants (e.g., cochlear implants, baclofen pumps etc.), presence of implanted metals that were not MRI-safe, degenerative neurological disorders, history of seizures, and leg bone mineral density T score < 1.5. People with AIS A were included to establish reorganization of spinal neural circuits when descending input is minimal. All participants refrained from caffeine, alcohol, and strenuous exercise for 12 h, and recreational drugs for 2 weeks before the first test. All participants gave their written informed consent prior to beginning the study and all experimental protocols were performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the City University of New York (IRB No: 2017-0261) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04624607).

Design

This was a single-blind randomized clinical trial. Participants completed an average of 26 ± 4.83 1-h locomotor training sessions with TMS paired with thoracolumbar transspinal stimulation both delivered during assisted stepping in a robotic gait orthosis system (Lokomat 6 Pro®, Hocoma, Switzerland). Participants were randomized to receive either transspinal-TMS (N = 5) or TMS-transspinal (N = 6) PAS (Table 1). A computer generated simple-randomization sequence was used so that a random ordered list of transspinal-TMS and TMS-transspinal interventions was created. As participants were recruited, they were assigned the next available intervention. Three participants completed both interventions with a 6-month washout period (identified in Table 1), while the second intervention was not randomized. The other participants were unable to participate in both interventions. Participants were blind to the PAS protocol and could not distinguish the order of stimuli because of the small interstimulus interval (ISI) between TMS and transspinal stimulation. Each participant completed two experimental testing sessions for recording the TA flexion reflex at least 1 day before starting the intervention and then again, the day after the last training session. For a group of the same participants, we have recently reported on the soleus H-reflex neurophysiological changes (Pulverenti et al. 2021) as one of the primary outcomes of the clinical trial. The training protocol has been described in detail (Pulverenti et al. 2021), and a summary will be reported here.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and training intervention settings

| Participant ID | Gender | Injury level | AIS scale | Time since injury (years) | Number of training sessions | Etiology | Tested TA | MEP latency (ms) | TEP latency (ms) | ISI (ms) | Medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training | |||||||||||

| LR01a | M | C4 | D | 15 | 30 | T | LL | 37.6 | 20.2 | 15.9 | None |

| LR04b | M | C5 | C | 5 | 20 | T | RL | 37.7 | 19.0 | 17.2 | Aspirin 80 mg 1 × D; Oxybutynin 10 mg 1 × D; Pravastatin 40 mg 1 × D; Pericolace 2 × D |

| LR05 | F | T12 | A | 4 | 19 | T | RL | – | 20.6 | 15.5 | Amitriptyline 25 mg 1 × D; Gabapentin 800 mg 3 × D; Tramadol 50 mg 2 × D |

| LR06c | M | T11 | D | 10 | 30 | T | RL | 38.2 | 20.2 | 16.5 | Gabapentin 100 mg 1 × D; Percocet 10 mg (as needed) |

| LR07 | M | C4 | C | 7 | 30 | T | LL | 37.8 | 22.0 | 14.3 | Baclofen 10 mg 4 × D; Bisacodyl 3 × D; Gabapentin 300 mg 2 × D; Oxybutynin 10 mg 3 × D; Oxycodone 10 mg 1 × D; Senekot 3 × D |

| Mean | 4 M, 1F | 25.8 | 3RL, 2LL | ||||||||

| SD | 5.2 | ||||||||||

| TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training | |||||||||||

| LR11a | M | C4 | D | 15 | 30 | T | LL | 38.4 | 20.4 | 16.5 | None |

| LR12c | M | T11 | D | 10 | 30 | T | RL | 38.6 | 20.8 | 16.3 | Gabapentin 100 mg 1 × D; Percocet 10 mg (as needed) |

| LR14 | M | T8 | A | 3 | 20 | T | RL | – | 20.0 | 15.5 | Oxybutynin |

| LR15b | M | C5 | C | 5 | 23 | T | RL | 38.4 | 20.0 | 16.9 | Aspirin 81 mg 1 × D; Oxybotin 15 mg 2 × D; Pravastatin 40 mg 1 × D; Pericolace 2 × D |

| LR20 | F | C4 | C | 8 | 26 | T | RL | 30.0 | 15.0 | 13.5 | Acetaminophen 500 mg 4 × D; Amitriptyline 10 mg 1 × D; Baclofen 20 mg 3 × D; Cyclobenzaprine 10 1 × D; Oxybutynin 10 mg 1 × D |

| LR21 | M | C7 | C | 3 | 31 | T | RL | 40.0 | 20.0 | 18.5 | Gabapentin 700 mg 3 × D; Oxybutynin 10 mg 1 × D |

| Mean | 5 M, 1F | 26.6 | 5RL, 1LL | ||||||||

| SD | 4.1 | ||||||||||

Bold text indicates totals, averages, and standard deviations where appropriate

Injury level corresponds to the neurological level of injury. The American Spinal Cord Injury Impairment Scale (AIS) is indicated for each subject based on sensory and motor evaluation per AIS guidelines. The number of transspinal and transcortical paired associative stimulation and assisted step training sessions is indicated for each participant. Motor-evoked potential (MEP), trannspinal-evoked potential, and medication was taken at similar times per day. xD times daily; M male; F female; C cervical; T thoracic; T/NT traumatic/non-traumatic

LR01 and LR11 are the same participant and completed both interventions

LR04 and LR15 are the same participant and completed both interventions

LR06 and LR12 are the same participant and completed both interventions

Paired-associative stimulation (transspinal and TMS) during locomotor training

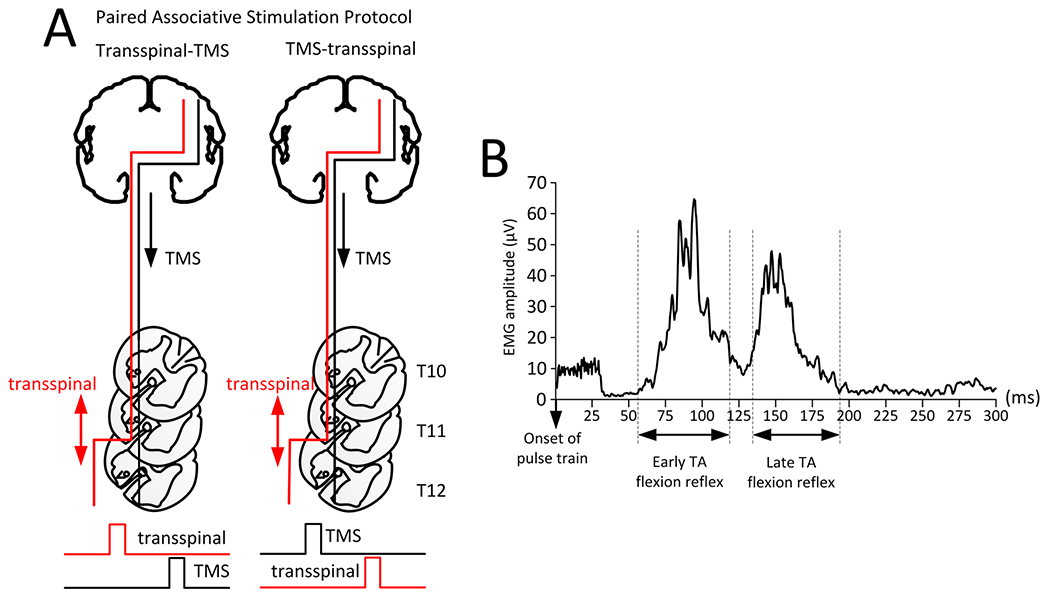

Transspinal-TMS and/or TMS-transspinal PAS (Fig. 1A) were delivered during the stance phase of robotic-assisted step training. The Magstim and Digitimer stimulator were triggered based on threshold signals from a foot switch placed on the leg targeted by TMS. Paired stimulation was delivered during assisted stepping every two to three steps in blocks of 10-min, with 2-min of no stimulation between each 10-min block. A total of 240 paired stimuli were delivered during each training session, resulting in 40-min of PAS and 20-min of stepping without PAS. Transspinal and TMS were delivered at standing soleus TEP and MEP threshold, respectively. In the participants that MEPs were absent (LR05 and LR14), TMS was set at the maximum tolerable intensity by the participant, while 15.5 ms ISI was chosen based on data from a previous study (Dixon et al. 2016).

Fig. 1.

Paired-associative stimulation (PAS) protocols. A Schematic detailing of the transspinal-TMS (left) and TMS-transspinal (right). In both protocols, transspinal stimulation produces orthodromic and antidromic excitation of large muscle afferents, orthodromic excitation of motor axons via depolarization of motoneurons, and excitation of ascending dorsal column fibers. The interstimulus interval (ISI) between TMS and transspinal stimulation was estimated based on Eq. 1. For both protocols, the ISI was used to set the order of triggering pulses to the Magstim or constant current stimulator. The ISI allowed transspinal induced excitation of dorsal columns to interact with TMS-evoked descending motor volleys at their site of origin within the primary motor cortex (transspinal-TMS PAS protocol), and TMS-evoked motor volleys to arrive at corticospinal presynaptic terminals of spinal motoneurons before transspinal stimulation transynaptically activated spinal motoneurons (TMS-transspinal PAS protocol). B Rectified EMG tracing of early and late TA flexion reflex from a single participant. The analysis window for the early TA flexion reflex started 60 ms after the first pulse in the stimulation train with 40 ms duration. The analysis window for the late TA flexion reflex started 130 ms after the first pulse with a duration of 130 ms

The conduction time from primary motor cortex to motoneuron synapse was estimated based on Eq. 1, in which we used the TEP latency to replace the root latency (Taylor and Martin 2009; Bunday and Perez 2012). The root latency was replaced by the TEP latency because they are similar as both can be evoked by electrical and magnetic stimulation of the spinal cord (Knikou 2013a, b). The conduction time found from Eq. 1 was used to set the timing of pulses between TMS and transspinal stimulation. We used the conduction time to deliver TMS-transspinal or transspinal-TMS paired stimulation during assisted stepping. Individual MEP latencies, TEP latencies, and ISIs for both paired stimulation protocols are presented in Table 1.

| (1) |

The ISI used for the TMS-transspinal protocol, aimed to have corticospinal volleys arrive at corticospinal-motoneuronal synapses before spinal motoneurons over multiple spinal segments were depolarized by transspinal stimulation. This was based on evidence that: (1) TMS-induced motor volleys are recorded from the upper thoracic level within 4 ms at a conduction velocity of ~ 62 m/s (Berardelli et al. 1990); (2) MEPs have an average central motor conduction time to ankle muscle motoneuron pools of ~ 15–19 ms in individuals with SCI (Brunhölzl and Claus 1994); and (3) TEPs and MEPs interact at the spinal level with summation of responses occurring when TMS precedes transspinal stimulation by ISIs of 8–25 ms (Roy et al. 2014; Knikou 2014).

Alternatively, the ISIs in the transspinal-TMS protocol aimed to excite posterior-root afferents and dorsal columns afferents by transspinal stimulation to affect descending motor volleys at their site of origin. The transspinal-TMS ISI was based on evidence that stimulation of the spinal roots at the thoraco-lumbar spinal level elicit somatosensory evoked cortical potentials with latencies of approximately 12 ms in healthy individuals and from 13 to 20 ms in individuals with spinal disorders (Ertekin et al. 1984; Berić et al. 1986; Paradiso et al. 1995), supporting transspinal stimulation-induced afferent regulation of corticospinal volleys at their site of origin at times as early as 12 ms.

For both PAS protocols, we followed our previously published procedures to deliver transspinal stimulation (Murray and Knikou 2019b; Knikou and Murray 2019; Pulverenti et al. 2021). Briefly, cathodal transspinal stimulation was delivered by a constant current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer, Hertfordshire, UK) with a self-adhesive electrode (Uni-Patch™, 10.2×5.1 cm2, Wabasha, MA, USA) placed vertically at the T10 spinous process covering T10 to L1-2 vertebrae. Consistent stimulation area among sessions was ensured via marking of the stimulating area with Tegaderm transparent film (3 M Healthcare, St. Paul, MN, USA). The anode electrodes were placed either on the abdominal muscles or iliac crests based on comfort levels reported by each participant. Similarly, TMS was delivered based on our previously published procedures (Mackey et al. 2016; Knikou 2017; Murray et al. 2019; Pulverenti et al. 2019). We used a Magstim 200 stimulator (Magstim, Whitland, UK) and a double-cone coil (110 mm diameter) to deliver TMS over the primary motor cortex with the coil orientated to induce a posterior to anterior current. With participants seated, we probed for the most optimal position based to the minimum intensity needed to evoke MEPs of at least 100 μV (Rossini et al. 2015). The point was marked on an EEG cap and held in place with a chin strap. This position was checked regularly during training and the optimal stimulation position was re-confirmed at the start of every week along with the MEP threshold.

Locomotor training

All participants received locomotor training with the Lokomat 6 Pro® for 5 days/week, 1 h/day for ~ 5 weeks. Over the course of the intervention, the treadmill speed, body weight support (BWS), and leg guidance force (LGF) of the robotic gait orthosis were adjusted based on our previous clinical trials on locomotor training in humans with SCI (Knikou 2013c; Smith et al. 2015; Pulverenti et al. 2021). BWS and LGF were adjusted to minimize knee buckling and ankle rolling during stepping (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant treadmill and robotic-gait orthosis settings before and after Transspinal-TMS and TMS-transspinal PAS combined with locomotor training

| Participant ID | Speed (km/h) |

BWS (kg) |

LGF (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training | ||||||

| LR01a | 2.2 | 2.6 | 21 | 15 | 70 | 50 |

| LR04b | 1.9 | 2.6 | 50 | 61 | 100 | 90 |

| LR05 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 53 | 52 | 100 | 90 |

| LR06c | 2.1 | 2.2 | 53 | 26 | 90 | 64 |

| LR07 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 43 | 43 | 80 | 70 |

| t-Test | 0.0027 | 0.33 | 0.077 | |||

| TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training | ||||||

| LR11a | 2.3 | 2.4 | 17 | 6 | 65 | 38 |

| LR12c | 2.1 | 2.1 | 7 | 15 | 70 | 30 |

| LR14 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 45 | 40 | 100 | 100 |

| LR15b | 1.7 | 1.7 | 61 | 43 | 80 | 96 |

| LR20 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 16 | 23 | 70 | 46 |

| LR21 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 36 | 33 | 100 | 100 |

| t-Test | 0.381 | 0.364 | 0.214 | |||

The treadmill speed, body weight support (BWS), and leg guidance force (LGF) is indicated for each participant from the first training session (before) to the last training session (after)

LR01 and LR11 are the same participant and completed both interventions

LR04 and LR15 are the same participant and completed both interventions

LR06 and LR12 are the same participant and completed both interventions

Flexion reflex before and after stimulation and locomotor training

The flexion reflex was recorded from the TA muscle (right leg N = 8; left leg N = 3) with a single differential bipolar surface electrodes of fixed inter-electrode distance (2.5 cm; Motion Lab Systems Inc., Baton Rouge, LA, USA) and evoked according to methods previously employed in human participants (Knikou and Conway 2005; Knikou et al. 2009; Zaaya et al. 2020, 2021). With participants seated, a pulse train of 30-ms duration (1-ms pulses at 300 Hz) was delivered to the medial arch or sural nerve at the lateral malleolus of the foot by a constant current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer Ltd., Hertfordshire, UK). Medial arch stimulation was delivered when lymphedema or swelling in the right ankle made sural nerve stimulation difficult even at remarkably high intensities. The pulse train was triggered by customized Spike 2 scripts via a 1401 plus analog-to-digital interface (CED Ltd., England). The optimal stimulation site for the TA flexion reflex with participants seated was based on present early or late component reflex EMG activity in the tested TA muscle at the lowest stimulation intensity with concomitant absent activity in triceps surae and toe extension that signifies excitation of plantar nerve axons (toe extensors). The flexion reflex was recorded at 1.3 multiples of the reflex threshold established during standing with the stimulated leg semiflexed. During stepping, the duration of the step cycle was divided into 16 equal bins based on the foot switch signals for heel contact and toe-off (i.e., bin 1 corresponded to heel contact, bin 8 to stance-to swing transition, bin 12 to mid-swing, and bin 16 to swing-to-stance transition) and multiple TA flexion reflexes were recorded randomly over the 16 different bins over the step cycle.

Data analysis and statistics

EMG signals during stepping (with and without stimulation) were full-wave rectified, high-pass filtered at 20 Hz and low-pass filtered at 500 Hz. Offline analysis started with identification of the responses in the tested TA muscle with a customized Labview script. To quantify the flexion reflex, two analysis windows were used (Knikou et al. 2009). The first window started at 60 ms after the first pulse in the train with duration of 40 ms (early component), and the second window started at 130 ms post pulse train with duration of 130 ms (late component). A representative example of windows for measuring the flexion reflex components is shown in Fig. 1B.

For each bin of the step cycle, the full wave integrated area of the early- and late-latency response was calculated and averaged separately for steps with and without medial arch or sural nerve stimulation. For each participant, the average EMG of non-stimulated steps (control EMG) was subtracted from the average EMG of stimulated steps (early- or late-latency reflex EMG) at identical time windows and bins to allow estimation of the net flexion reflex modulation (Zehr et al. 1997, 1998; Knikou et al. 2009). This subtraction resulted in negative EMG values when the average reflex EMG value was smaller than the control EMG and positive EMG values when the average reflex EMG was larger than the control EMG. For each bin, the average subtracted reflex EMG was then normalized to the maximal control EMG to compare across participants. Statistical significance before and after each intervention was established separately for the early and late TA flexion reflex and for each training protocol with a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance [16 bins at 2 (before and after) levels], using SigmaPlot 11.0. Data were prior tested for normality and equal variance.

The background EMG activity of the TA muscle for each bin was estimated from the mean value of the rectified and filtered EMG for a duration of 50 ms (high-pass filtered at 20 Hz, rectified, and low-pass filtered at 400 Hz), beginning 100 ms before medial arch or sural nerve stimulation. The mean amplitude of the early- and late-components of the TA flexion reflex was plotted on the y-axis versus the TA background activity (normalized to the maximal control EMG) on the x-axis, and a linear least-square regression was fitted to the data. This analysis was conducted separately for each participant and for the pool data. In all statistical tests, significant differences were established at 95% of confidence level. Results are presented as mean values along with the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Figure 2 shows raw average traces of TA EMG activity recorded before and after transspinal-TMS PAS (Fig. 2A) and TMS-transspinal PAS (Fig. 2B) locomotor training during assisted stepping. It is evident that transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training significantly reduced the amplitude of the flexion reflex in all bins of the step cycle. In the TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training intervention, the late flexion reflex was reduced and replaced by an earlier component supporting a strong reorganization of spinal flexion reflex circuits and pathways.

Fig. 2.

Raw average EMG traces of tibialis anterior (TA) activity before and after transspinal-TMS PAS (A) and TMS-transspinal (B) and locomotor training at each bin of the step cycle. In the transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training protocol, a generalized suppression of the flexion reflex excitability is apparent, while in the TMS-transspinal and locomotor training the long latency TA flexion reflex was suppressed and replaced by a response occurring at shorter latency

The average normalized subtracted short-latency (Fig. 3A) and long-latency (Fig. 3D) TA flexion reflex amplitude during stepping at each bin of the step cycle from all participants before and after transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training are shown in Fig. 3. The short-latency TA flexion reflex was not modulated in a phase-dependent manner as a function of the bins of the step cycle (F15,94 = 1.02, P = 0.437) but a significant effect before and after training was found (F1,94 = 5.47, P = 0.021). However, a significant interaction between time and bins was not found (F15.1 = 0.39, P = 0.978). During stepping, the short-latency TA flexion reflex amplitude showed moderate linear relationship to the TA background EMG activity before (R2 = 0.258) and after (R2 = 0.47) training (Fig. 3B). The slope and intercept of the linear relationship between the short-latency TA flexion reflex and background EMG activity were not significantly different before and after transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training (P > 0.05; Fig. 3C), indicating no changes in reflex gain or reflex threshold, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Tibialis anterior (TA) flexion reflex modulation during assisted stepping before and after transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training. The early (A) and late (D) TA flexion reflex mean amplitude before (black) and after (red) transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training, along with the early (B) and late (E) TA flexion reflex amplitude plotted against the TA EMG background activity. The amplitude of the slope and intercept from the linear relationship between the mean amplitude of the early (C) and late (F) TA flexion reflexes and TA EMG background

The long-latency TA flexion reflex was modulated based on time (F1,110 = 26.45, P < 0.001) but not across the different bins of the step cycle (F15,110 = 1.095, P= 0.406), while a significant interaction between time and bins was not found (F1.15 = 0.165, P = 1.00). The 1 TA flexion reflex during stepping showed absent relationship to the TA background EMG activity before (R2 = 0.05) and after (R2 = 0.05) training (Fig. 3E). The slope and intercept were not significantly different before and after transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training (Fig. 3F), indicating no change in reflex gain or reflex threshold for the late TA flexion reflex after training.

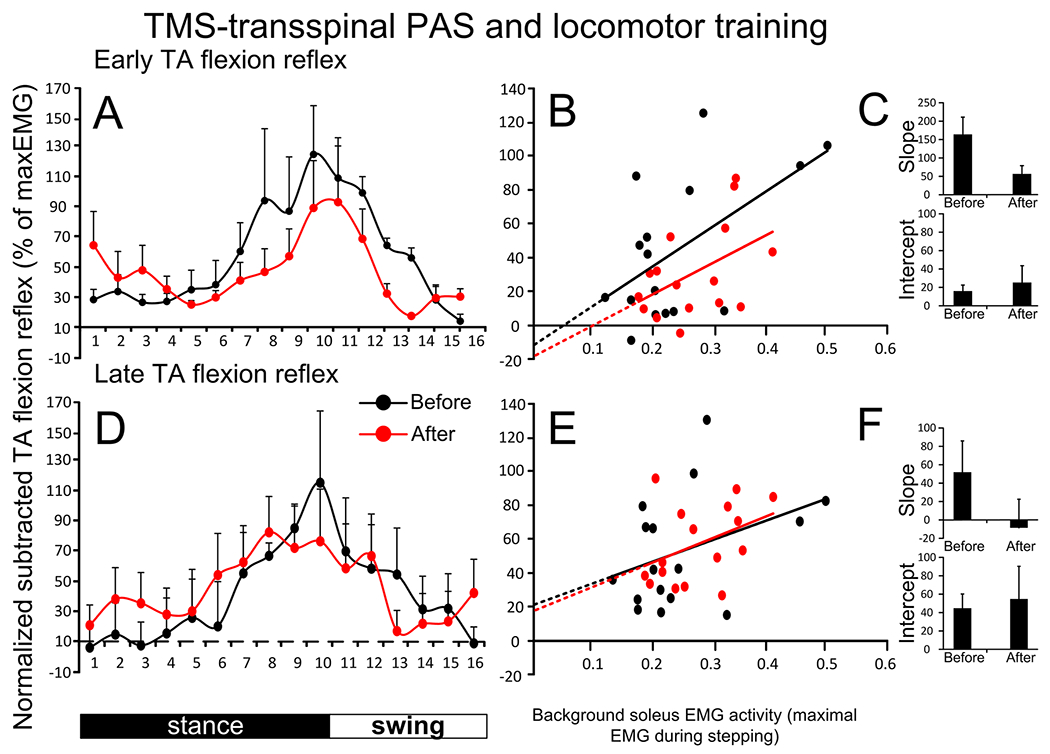

Figure 4 shows the average normalized subtracted early (Fig. 4A) and late (Fig. 4D) TA flexion reflex amplitude during stepping at each bin of the step cycle from all participants before and after TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training. The early flexion reflex before or after intervention was depressed at mid-stance (bins 2–7) with maximum reflex facilitation at mid-swing, similar to that we have previously reported (Knikou et al. 2009). The early TA flexion reflex was modulated in a phase-dependent manner as a function of the bins of the step cycle (F15,64 = 2.63, P = 0.004) but not of time (F1,64 = 1.79, P = 0.185), while a significant interaction between time and bins was not found (F15,64=0.55, P=0.898). During stepping, the early TA flexion reflex amplitude showed a minimal to moderate negative linear relationship to the TA background EMG activity before (R2 = 0.323) and after (R2 = 0.219) training (Fig. 4B). The slope and intercept of the linear relationship between the early TA flexion reflex and background EMG activity were not significantly different before and after TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training (P > 0.05; Fig. 4C), indicating no changes in reflex gain or reflex threshold. The late TA flexion reflex was not modulated based on time (F1,64 = 0.272, P = 0.714) or different bins of the step cycle (F15,64 = 0.19, P = 0.198), while a significant interaction between time and bins was not found (F1,15 = 0.27, P = 0.99). The late TA flexion reflex during stepping showed minimal negative linear relationship to the TA background EMG activity before (R2 = 0.138) and after (R2=0.166) training (Fig. 4E). The slope and intercept were not significantly different before and after TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training (Fig. 4F), indicating no change in reflex gain regarding the late component or reflex threshold.

Fig. 4.

Tibialis anterior (TA) flexion reflex modulation during assisted stepping before and after TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training. The early (A) and late (D) TA flexion reflex mean amplitude before (black) and after (red) TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training, along with the early (B) and late (E) TA flexion reflex amplitude plotted against the TA EMG background activity. The amplitude of the slope and intercept from the linear relationship between the mean amplitude of the early (C) and late (F) TA flexion reflexes and TA EMG background

Discussion

This single-blind randomized clinical trial showed that transspinal-TMS PAS delivered during assisted step training downregulated the TA flexion reflex during stepping in people with varying levels of sensorimotor dysfunction due to chronic SCI. The depression of the early or late component of the flexion reflex during stepping was mediated most likely through changes in the activity of spinal interneuronal circuits directly affecting the function of spinal locomotor centers.

In the TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training protocol, both the early and late TA flexion reflex before the intervention were modulated in a phase-dependent manner being progressively decreased during the stance phase followed by increased amplitude at stance-to-swing, reaching peak facilitation at early and late swing phases (Fig. 2A, D). This pattern is similar to the previously reported phase-dependent modulation of cutaneomuscular responses during walking following non-nociceptive stimulation of skin, sensory or mixed peripheral nerves (Duysens et al. 1993; Tax et al. 1995; Van Wezel et al. 1997; Zehr et al. 1997, 1998; Knikou et al. 2009). No changes in the amplitude of the early or late TA flexion reflex were found after TMS-transspinal PAS and locomotor training (Fig. 4A, D), consistent to lack of changes for the left or right soleus H-reflex for the same patients and type of intervention (Pulverenti et al. 2021).

In the transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training (Fig. 3A), the early TA flexion reflex was not modulated in a phase-dependent manner before the intervention suggesting different baseline reflex excitability patterns among groups, and substantial suppression of this reflex component. In contrast, while the long-latency TA flexion reflex (Fig. 3D) exhibited more amplitude modulation, no significant differences among the step cycle phases were found. After intervention, the early and late TA flexion reflexes were significantly depressed throughout the step cycle (Fig. 3A, D). This result is consistent with the decreased soleus H-reflex excitability at rest, depression of the early TA flexion reflex throughout the step cycle upon transspinal conditioning stimulation during walking in healthy participants (Zaaya et al. 2020), but opposite to the soleus H-reflex facilitation during mid- and late stance phase (Pulverenti et al. 2021). These findings support that transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training affect differently flexor and extensor spinal reflexes in a manner that supports locomotion.

The different behavior of the early TA flexion reflex in the two randomized groups may be the result of many factors associated to the nature of SCI. After SCI in humans, the short-latency flexion reflex is irregularly observed or even completely absent, while late or long-latency long-lasting flexion reflexes, which are considered precursors of flexor withdrawal reflexes and spasms, are released (Roby-Bramy and Bussell 1987; Knikou and Conway 2005; Dietz et al. 2009). The long-latency flexion reflex has a similar neuronal organization to that described in spinalized animals treated with l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA, a precursor of dopamine, noradrenaline, and epinephrine) and Nialamide (Andén et al. 1966; Jankowska et al. 1967a, b; Roby-Brami and Bussel 1990, 1992), and thus, is considered a part of the spinal half-center of locomotion.

While we cannot state with certainty the neuronal pathway involved, it is likely that the depression of flexion reflex excitability after transspinal-TMS PAS and locomotor training was driven by concomitant changes at pre- and post-motoneuronal levels. Flexion reflex afferents (FRA) evoke primary afferent inhibition in their own terminals (Eccles et al. 1962), and presynaptic inhibition of Ia transmission to alpha motoneurons in humans with motor complete SCI (Roby-Brami and Bussel 1990). Further, primary afferent depolarization of group I afferents is modulated in a phase-dependent manner (Ménard et al. 2002, 2003). Based on this evidence, we can propose that transspinal-TMS during assisted step training affected the ongoing presynaptic inhibition. Depression of flexion reflex excitability could have also occurred concurrently at a post alpha motoneuronal level. This is supported by the depression of the TA MEPs by suprathreshold transspinal conditioning stimulation (Pulverenti et al. 2019) and TA flexion reflex and TA MEP facilitation following TMS and medial arch foot stimulation respectively at times that neuronal interaction between both stimuli occurs at supraspinal levels (Mackey et al. 2016). Collectively we can suggest that transspinal stimulation drove the TA flexion reflex depression given the facilitatory reflex actions between the descending motor volleys and cutaneomuscular responses in humans, supporting ongoing results on that transspinal stimulation at low or high frequencies combined with brain stimulation or alone, depresses flexor or extensor spinal reflex excitability but increases recruitment of motoneurons and net motor output in people with SCI (Murray and Knikou 2019a, b; Knikou and Murray 2019; Zaaya et al. 2021).

Our protocol combined two different interventions to resemble treatment approaches in clinical practice, and our neurophysiological measures were indirect. Thus, we cannot determine with certainty the neuronal pathways involved or neural sites of primary action of the observed effects. Simulation models that can encompass the complex anatomy and physiology of the spinal cord’s neuronal organization (Côté et al. 2018) and/or direct recordings are needed. Regardless, pairing transspinal with brain stimulation may augment further the benefits of locomotor training since neither transspinal nor brain stimulation produces neuroplasticity opposite to that produced by locomotor training alone (Knikou 2013c).

Limitations of the study

There are certain limitations of the study that need consideration. Notably, no sham stimulation or control group, receiving only locomotor training or brain/transspinal stimulation was used. Inclusion of these groups would be highly beneficial to comparatively provide the additional benefits of paired brain and transspinal stimulation during locomotor training. Because transspinal stimulation excites different classes of neurons (i.e., sensory nerves, motoneurons and spinal interneurons) over multiple segments, it is difficult to directly compare the results in the current study with those from studies utilizing peripheral nerve stimulation in PAS protocols, which target one specific group of motoneurons and muscle.

The methods to calculate and estimate the timing of TMS relative to transspinal stimulation were not from direct recordings. Consequently, it is possible that in the TMS-transspinal stimulation protocol, the ISI resulted in depolarization of motoneurons by transspinal stimulation before the first TMS-induced corticospinal volley reached the synapse. However, repetitive firing of corticospinal neurons occurs in response to TMS-evoked multiple descending volleys that last several milliseconds, transspinal stimulation elicits long-lasting synaptic actions, and MEPs and TEPs summate over a range ISIs when TMS is delivered before transspinal stimulation (Edgley et al. 1990; Rothwell et al. 1991; Roy et al. 2014; Knikou 2014; Rossini et al. 2015; Dixon et al. 2016). Conversely, in the transspinal-TMS protocol, the ISI was not based on latency of somatosensory-evoked potential activity following transspinal stimulation, thus caution should be exercised when inferring whether transspinal-evoked volleys interacted with TMS volleys at specific cortical sites. Utilizing PAS protocols during exercise for SCI rehabilitation, such as the paired brain and transspinal stimulation during locomotor training in the current study, may be highly beneficial to improve motor function, yet the complexity of such protocols presents a significant barrier to clinical viability. Therefore, future studies should examine if the present PAS protocol has neuromodulatory effects after cessation of the stimulation, and if it can be used to prime nervous system function before exercise-based rehabilitation.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence on the neuroplasticity following the novel protocol of pairing transspinal with brain stimulation during robotic-assisted step training in people with chronic motor complete or incomplete SCI. It is evident that brain and transspinal PAS being delivered during assisted stepping promotes functional reflex reorganization in a manner similar to that reported by locomotor training alone. Depression of an exaggerated flexion reflex could potentially facilitate appropriate control between flexors and extensors, while enabling more physiological transitions from stance to swing and vice versa. In conclusion, transspinal and TMS PAS warrant further investigation onto understanding better sites of neural actions that may lead to development of more suitable protocols that can effectively maximize the activity-dependent neuroplasticity produced by exercise and stimulation in people with SCI.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants and their care givers for their commitment during participation in the research study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Spinal Cord Injury Research Board (SCIRB) of the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH), Wadsworth Center (Grants C32095GG, C33276GG), and, in part, by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), under grant number R01HD100544 awarded to Maria Knikou. Funding sources were not involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or decision to publish.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York (IRB no. 2017-0261). All participants gave informed consent before study enrollment and participation.

Trial registration number NCT04624607; Registered on November 12, 2020.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

References

- Andén N-E, Jukes MGM, Lundberg A, Vyklicky L (1966) The effect of DOPA on the spinal cord. 1. Influence on transmission from primary aflerents. Acta Physiol Scand 67:373–386. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1966.tb03324.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau H (2003) Locomotor training in neurorehabilitation: emerging rehabilitation concepts. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 17:3–11. 10.1177/0888439002250442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardelli A, Inghilleri M, Cruccu G, Manfredi M (1990) Descending volley after electrical and magnetic transcranial stimulation in man. Neurosci Lett 112:54–58. 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90321-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berić A, Dimitrijević MR, Sharkey PC, Sherwood AM (1986) Cortical potentials evoked by epidural stimulation of the cervical and thoracic spinal cord in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 65:102–110. 10.1016/0168-5597(86)90042-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunhölzl C, Claus D (1994) Central motor conduction time to upper and lower limbs in cervical cord lesions. Arch Neurol 51:245–249. 10.1001/ARCHNEUR.1994.00540150039013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunday KL, Perez MA (2012) Motor recovery after spinal cord injury enhanced by strengthening corticospinal synaptic transmission. Curr Biol 22:2355–2361. 10.1016/J.CUB.2012.10.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunday KL, Urbin MA, Perez MA (2018) Potentiating paired corticospinal-motoneuronal plasticity after spinal cord injury. Brain Stimul. 10.1016/J.BRS.2018.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano DV, Merzenich MM (1998) Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annu Rev Neurosci 21:149–186. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes M, Thickbroom GW, Valls-Sole J et al. (2011) Spinal associative stimulation: a non-invasive stimulation paradigm to modulate spinal excitability. Clin Neurophysiol 122:2254–2259. 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.02.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté MP, Murray LM, Knikou M (2018) Spinal control of locomotion: individual neurons, their circuits and functions. Front Physiol 9:784. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Harkema SJ, Dy CJ et al. (2007) Modulation of multisegmental monosynaptic responses in a variety of leg muscles during walking and running in humans. J Physiol 582:1125–1139. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Y, Poo M-M (2006) Spike timing-dependent plasticity: from synapse to perception. Physiol Rev 86:1033–1048. 10.1152/physrev.00030.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Grillner S, Trepp A et al. (2009) Changes in spinal reflex and locomotor activity after a complete spinal cord injury: a common mechanism? Brain 132:2196–2205. 10.1093/BRAIN/AWP124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Ibrahim MM, Santora D, Knikou M (2016) Paired associative transspinal and transcortical stimulation produces plasticity in human cortical and spinal neuronal circuits. J Neurophysiol 116:904–916. 10.1152/jn.00259.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duysens J, Tax AAM, Trippel M, Dietz V (1993) Increased amplitude of cutaneous reflexes during human running as compared to standing. Brain Res 613:230–238. 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90903-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Kostyuk PG, Schmidt RF (1962) Presynaptic inhibition of the central actions of flexor reflex afferents. J Physiol 161:258–281. 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton VR, Tillakaratne NJK, Bigbee AJ et al. (2004) Plasticity of the spinal neural circuitry after injury. Annu Rev Neurosci 27:145–167. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgley SA, Eyre JA, Lemon RN, Miller S (1990) Excitation of the corticospinal tract by electromagnetic and electrical stimulation of the scalp in the macaque monkey. J Physiol 425:301. 10.1113/JPHYSIOL.1990.SP018104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertekin C, Sarica Y, Öçkardeşler L (1984) Somatosensory cerebral potentials evoked by stimulation of the lumbo-sacral spinal cord in normal subjects and in patients with conus medullaris and cauda equina lesions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 59:57–66. 10.1016/0168-5597(84)90020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO (1949) The organization of behavior: a neuropsychological theory. Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Jukes MGM, Lund S, Lundberg A (1967a) The effect of DOPA on the spinal cord 6. Half-centre organization of interneurones transmitting effects from the flexor reflex afferents. Acta Physiol Scand 70:389–402. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1967.tb03637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Jukes MGM, Lund S, Lundberg A (1967b) The effect of DOPA on the spinal cord 5. Reciprocal organization of pathways transmitting excitatory action to alpha motoneurones of flexors and extensors. Acta Physiol Scand 70:369–388. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1967.tb03636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram G, Stinear JW (2007) Contralesional paired associative stimulation increases paretic lower limb motor excitability poststroke. Exp Brain Res 185:563–570. 10.1007/S00221-007-1183-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo HJ, Perez MA (2020) Corticospinal-motor neuronal plasticity promotes exercise-mediated recovery in humans with spinal cord injury—pubMed. Brain 143:1356–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2010a) Neural control of locomotion and training-induced plasticity after spinal and cerebral lesions. Clin Neurophysiol 121:1655–1668. 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2010b) Plantar cutaneous afferents normalize the reflex modulation patterns during stepping in chronic human spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 103:1304–1314. 10.1152/jn.00880.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2013a) Neurophysiological characterization of transpinal evoked potentials in human leg muscles. Bioelectromagnetics 34:630–640. 10.1002/bem.21808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2013b) Neurophysiological characteristics of human leg muscle action potentials evoked by transcutaneous magnetic stimulation of the spine. Bioelectromagnetics 34:200–210. 10.1002/bem.21768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2013c) Functional reorganization of soleus H-reflex modulation during stepping after robotic-assisted step training in people with complete and incomplete spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res 228:279–296. 10.1007/s00221-013-3560-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2014) Transpinal and transcortical stimulation alter corticospinal excitability and increase spinal output. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2017) Spinal excitability changes after transspinal and transcortical paired associative stimulation in humans. Neural Plast. 10.1155/2017/6751810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M, Conway BA (2005) Effects of electrically induced muscle contraction on flexion reflex in human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43:640–648. 10.1038/sj.sc.3101772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M, Murray LM (2019) Repeated transspinal stimulation decreases soleus H-reflex excitability and restores spinal inhibition in human spinal cord injury. PLoS One 14:e0223135. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M, Angeli CA, Ferreira CK, Harkema SJ (2009) Flexion reflex modulation during stepping in human spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res 196:341–351. 10.1007/s00221-009-1854-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamy JC, Russmann H, Shamim EA et al. (2010) Paired associative stimulation induces change in presynaptic inhibition of Ia terminals in wrist flexors in humans. J Neurophysiol 104:755–764. 10.1152/jn.00761.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey AS, Uttaro D, McDonough MP et al. (2016) Convergence of flexor reflex and corticospinal inputs on tibialis anterior network in humans. Clin Neurophysiol 127:706–715. 10.1016/J.CLINPH.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Lübke J, Frotscher M, Sakmann B (1997) Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs the increase in. Science 80(275):213–214. 10.1126/science.275.5297.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Gerstner W, Sjöström PJ (2011) A history of spike-timing-dependent plasticity. Front Synaptic Neurosci 3:1–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson JG, Miller RR, Perlmutter SI (2015) Targeted, activity-dependent spinal stimulation produces long-lasting motor recovery in chronic cervical spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:12193–12198. 10.1073/pnas.1505383112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard A, Leblond H, Gossard J-P (2002) Sensory integration in presynaptic inhibitory pathways during fictive locomotion in the cat. J Neurophysiol 88:163–171. 10.1152/jn.2002.88.1.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard A, Leblond H, Gossard JP (2003) Modulation of monosynaptic transmission by presynaptic inhibition during fictive locomotion in the cat. Brain Res 964:67–82. 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)04067-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier S, Russmann H, Simonetta-Moreau M, Hallett M (2007) Changes in spinal excitability after PAS. J Neurophysiol 97:3131–3135. 10.1152/jn.01086.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian K, Persy I, Rattay F et al. (2007) Posterior root–muscle reflexes elicited by transcutaneous stimulation of the human lumbosacral cord. Muscle Nerve 35:327–336. 10.1002/mus.20700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Dahlhaus F, Ziemann U, Classen J (2010) Plasticity resembling spike-timing dependent synaptic plasticity: the evidence in human cortex. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LM, Knikou M (2019a) Transspinal stimulation increases motoneuron output of multiple segments in human spinal cord injury. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LM, Knikou M (2019b) Repeated cathodal transspinal pulse and direct current stimulation modulate cortical and corticospinal excitability differently in healthy humans. Exp Brain Res 237:1841–1852. 10.1007/s00221-019-05559-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LM, Islam MA, Knikou M (2019) Cortical and subcortical contributions to neuroplasticity after repetitive transspinal stimulation in humans. Neural Plast. 10.1155/2019/4750768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso C, De Vito L, Rossi S et al. (1995) Cervical and scalp recorded short latency somatosensory evoked potentials in response to epidural spinal cord stimulation in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 96:105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulverenti TS, Anamul Islam M, Alsalman O et al. (2019) Transspinal stimulation decreases corticospinal excitability and alters the function of spinal locomotor networks. J Neurophysiol 122:2331–2343. 10.1152/jn.00554.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulverenti TS, Zaaya M, Grabowski M et al. (2021) Neurophysiological changes after paired brain and spinal cord stimulation coupled with locomotor training in human spinal cord injury. Front Neurol 12:627975. 10.3389/fneur.2021.627975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roby-Brami A, Bussel B (1987) Long-latency spinal reflex in man after flexor reflex afferent stimulation. Brain 110:707–725. 10.1093/brain/110.3.707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roby-Brami A, Bussel B (1990) Effects of flexor reflex afferent stimulation on the soleus H reflex in patients with a complete spinal cord lesion: evidence for presynaptic inhibition of Ia transmission. Exp Brain Res 81:593–601. 10.1007/BF02423509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roby-Brami A, Bussel B (1992) Inhibitory effects on flexor reflexes in patients with a complete spinal cord lesion. Exp Brain Res 90:201–208. 10.1007/BF00229272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz K, Williamon A, Rothwell JC (2007) Motorcortical excitability and synaptic plasticity is enhanced in professional musicians. J Neurosci 27:5200–5206. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0836-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol S, Frigon A (2011) Recovery of locomotion after spinal cord injury: some facts and mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci 34:413–440. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini PM, Burke D, Chen R et al. (2015) Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord, roots and peripheral nerves: Basic principles and procedures for routine clinical and research application. An updated report from an I.F.C.N Committee. Clin Neurophysiol 126:1071–1107. 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell J, Thompson P, Day B et al. (1991) Stimulation of the human motor cortex through the scalp. Exp Physiol 76:159–200. 10.1113/EXPPHYSIOL.1991.SP003485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy FD, Bosgra D, Stein RB (2014) Interaction of transcutaneous spinal stimulation and transcranial magnetic stimulation in human leg muscles. Exp Brain Res 232:1717–1728. 10.1007/s00221-014-3864-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg ED, Petersen N, Barajon I, Hultborn H (1998) Flexor reflex afferents reset the step cycle during fictive locomotion in the cat. Exp Brain Res 122:339–350. 10.1007/s002210050522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström PJ, Rancz EA, Roth A, Hausser M (2008) Dendritic excitability and synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev 88:769–840. 10.1152/physrev.00016.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Knikou M (2016) A review on locomotor training after spinal cord injury: reorganization of spinal neuronal circuits and recovery of motor function. Neural Plast. 10.1155/2016/1216258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Mummidisetty CK, Rymer WZ, Knikou M (2014) Locomotor training alters the behavior of flexor reflexes during walking in human spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 112:2164–2175. 10.1152/jn.00308.2014.-In [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Rymer WZ, Knikou M (2015) Locomotor training modifies soleus monosynaptic motoneuron responses in human spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res 233:89–103. 10.1007/s00221-014-4094-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Miller KD, Abbott LF (2000) Competitive Hebbian learning through spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci 3:919–926. 10.1038/78829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan K, Kunesch E, Cohen LG et al. (2000) Induction of plasticity in the human motor cortex by paired associative stimulation. Brain 123:572–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan K, Kunesch E, Benecke R et al. (2002) Mechanisms of enhancement of human motor cortex excitability induced by interventional paired associative stimulation. J Physiol 543:699–708. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tax AAM, Van Wezel BMH, Dietz V (1995) Bipedal reflex coordination to tactile stimulation of the sural nerve during human running. J Neurophysiol 73:1947–1964. 10.1152/jn.1995.73.5.1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Martin PG (2009) Voluntary motor output is altered by spike-timing-dependent changes in the human corticospinal pathway. J Neurosci 29:11708–11716. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2217-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wezel BMH, Ottenhoff FAM, Duysens J (1997) Dynamic control of location-specific information in tactile cutaneous reflexes from the foot during human walking. J Neurosci 17:3804–3814. 10.1523/jneurosci.17-10-03804.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaaya M, Pulverenti TS, Islam MA, Knikou M (2020) Transspinal stimulation downregulates activity of flexor locomotor networks during walking in humans. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 52:102420. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2020.102420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaaya M, Pulverenti TS, Knikou M (2021) Transspinal stimulation and step training alter function of spinal networks in complete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 71(7):1–8. 10.1038/s41394-021-00421-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr EP, Komiyama T, Stein RB (1997) Cutaneous reflexes during human gait: electromyographic and kinematic responses to electrical stimulation. J Neurophysiol 77:3311–3325. 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr EP, Stein RB, Komiyama T (1998) Function of sural nerve reflexes during human walking. J Physiol 507:305–314. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.305bu.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann U, Muellbacher W, Hallett M, Cohen LG (2001) Modulation of practice-dependent plasticity in human motor cortex. Brain 124:1171–1181. 10.1093/brain/124.6.1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.