Abstract

Objective:

Lack of judicious testing can result in the incorrect diagnosis of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), unnecessary CDI treatment, increased costs and falsely augmented hospital-acquired infection (HAI) rates. We evaluated facility-wide interventions used at the VA San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS) to reduce healthcare-onset, healthcare-facility–associated CDI (HO-HCFA CDI), including the use of diagnostic stewardship with test ordering criteria.

Design:

We conducted a retrospective study to assess the effectiveness of measures implemented to reduce the rate of HO-HCFA CDI at the VASDHS from fiscal year (FY)2015 to FY2018.

Interventions:

Measures executed in a stepwise fashion included a hand hygiene initiative, prompt isolation of CDI patients, enhanced terminal room cleaning, reduction of fluoroquinolone and proton-pump inhibitor use, laboratory rejection of solid stool samples, and lastly diagnostic stewardship with C. difficile toxin B gene nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) criteria instituted in FY2018.

Results:

From FY2015 to FY2018, 127 cases of HO-HCFA CDI were identified. All rate-reducing initiatives resulted in decreased HO-HCFA cases (from 44 to 13; P ≤ .05). However, the number of HO-HCFA cases (34 to 13; P ≤ .05), potential false-positive testing associated with colonization and laxative use (from 11 to 4), hospital days (from 596 to 332), CDI-related hospitalization costs (from $2,780,681 to $1,534,190) and treatment cost (from $7,158 vs $1,476) decreased substantially following the introduction of diagnostic stewardship with test criteria from FY2017 to FY2018.

Conclusions:

Initiatives to decrease risk for CDI and diagnostic stewardship of C. difficile stool NAAT significantly reduced HO-HCFA CDI rates, detection of potential false-positives associated with laxative use, and lowered healthcare costs. Diagnostic stewardship itself had the most dramatic impact on outcomes observed and served as an effective tool in reducing HO-HCFA CDI rates.

Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile is an anaerobic spore-forming and toxin-producing gram-positive rod. The etiologic agent of C. difficile infection (CDI), C. difficile is known to cause a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from asymptomatic carriage to gastrointestinal disease. When present, gastrointestinal disease can range from mild diarrhea to severe pseudomembranous colitis with toxic megacolon.1 The causative agent of antibiotic-associated colitis, C. difficile, is the most common cause of hospital-acquired infections, costing the United States healthcare system >$15,000 per hospital-onset case, and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality.2,3 While recent epidemiologic studies estimate a decline in the national burden of CDI and associated hospitalizations from 2011 to 2017, annual rates remain high with 462,100 cases and 20,500 deaths reported in 2017.4

Although C. difficile is the most common infectious cause of nosocomial diarrhea, it only represents 10%–20% of all cases of diarrhea encountered in the healthcare setting.5 Enteral feeding and medications (eg, laxatives, antibiotics, antiretrovirals, chemo-therapeutic agents, immunosuppressants and metformin) cause the majority of diarrhea in hospitalized patients.5 Additionally, concomitant laxative use is common in patients tested for CDI. Interestingly, studies suggest up to 20%–50% of adults residing in hospital or long-term care facilities can be asymptomatically colonized with C. difficile.6–8 Those colonized with C. difficile are just as likely to develop diarrhea due to the aforementioned causes, which can lead to an incorrect diagnosis of CDI when tested. The potential impact of laxative use on the specificity of CDI test results is particularly concerning. Previous studies have estimated that up to 44% of hospitalized patients tested for CDI received a laxative within 48 hours of testing.9,10

Like many other healthcare facilities in the United States, the VA San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHS) solely utilizes C. difficile toxin B gene nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for CDI diagnosis. However, NAAT alone cannot distinguish between active CDI and colonization. Lack of judicious testing can result in the incorrect diagnosis and unnecessary treatment of CDI, increased cost, falsely augmented healthcare onset, healthcare facility associated (HO-HCFA) CDI rates, and decreased Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement to healthcare facilities.11 Here, we performed a retrospective study evaluating the effectiveness of various interventions implemented at the VASDHS from 2015 to 2018 to curb HO-HCFA CDI rates. The interventions included improving hand hygiene compliance, ensuring timely isolation of C. difficile–positive patients, reducing hospital-wide fluoroquinolone antibiotic use, discouraging unnecessary proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, revising testing parameters to reject solid stool samples, and lastly implementing a diagnostic stewardship program including the use of a test ordering algorithm outlining patient criteria for CDI stool NAAT.

Materials and methods

Study design

A quality improvement project to reduce HO-HCFA CDI was instituted at the VASDHS by the infection prevention and control team and the antimicrobial stewardship program from October 2014 to September 2018. All data collected from the project were retrospectively analyzed. The purpose of the retrospective study was to evaluate the effectiveness of different stepwise interventions both individually and collectively at reducing HO-HCFA CDI rates. Quality assessment and quality improvement initiatives designed for VA purposes, including routine data collection and analysis for operational monitoring, evaluation, and program improvement purposes does not constitute research requiring institutional review board approval per VHA Handbook 1200.21 “VHA Operations Activities that May Constitute Research,” dated January 9, 2019.

Definitions

HO-HCFA CDI is defined by the National Health and Safety Network (NHSN) as any positive stool specimen collected on hospital day 4 or thereafter.12 Additionally, October 2014 to September 2015, October 2015 to September 2016, October 2016 to September 2017, and October 2017 to September 2018 were defined as VA fiscal years (FY)2015, FY2016, FY2017, and FY2018, respectively.

Interventions and C. difficile testing criteria

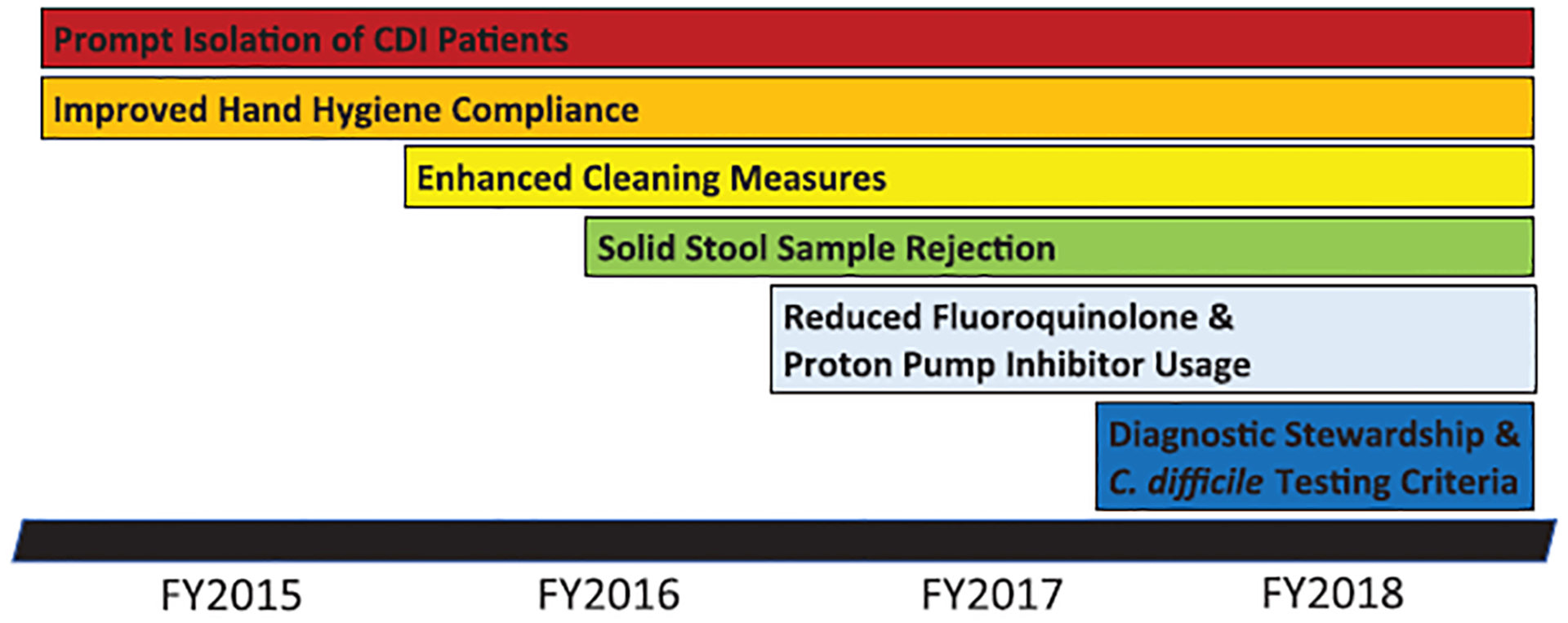

Interventions implemented from FY2015 to FY2017 included augmenting hand hygiene compliance, ensuring timely isolation of C. difficile–positive patients, reducing hospital-wide fluoroquinolone antibiotic use, discouraging unnecessary proton pump inhibitor use and revising testing parameters to reject solid stool samples sent for testing (Fig. 1). Furthermore, in 2018, a test-ordering algorithm was incorporated into the electronic medical record, outlining patient criteria for stool C. difficile toxin B gene NAAT. The testing criteria included at least 3 watery bowel movements in the past 24 hours, no new or additional laxatives in the past 24 hours, no initiation of tube feeds in the last 48 hours, and no CDI stool NAAT sent in the past 7 days. However, clinicians remained able to order testing even if criteria were not met and suspicion for CDI remained high.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of interventions implemented to reduce C. difficile infection rates at the VA San Diego Healthcare System. Abbreviations: CDI = C. difficile Infection, FY = Fiscal Year.

Data analysis

All individuals aged ≥18 years admitted to VASDHS with a positive C. difficile toxin B gene stool NAAT meeting the current NHSN definition for HO-HCFA CDI (diagnosed on or after the 4th calendar day of hospitalization) were identified. Various patient characteristics including demographic factors, comorbidities, CDI risk factors (antibiotic exposure, CDI history, immunosuppression, proton pump inhibitor use), and generators of potential false-positive CDI (tube feeding or laxative use at time of testing) were analyzed. Outcome measures included number of CDI cases, CDI severity, days of hospitalization, level of care, CDI-related costs and CDI treatment costs. CDI-related costs refer to the cost of hospitalization for CDI and other comorbidities based on length of stay and level of care (medical/surgical vs intensive care unit) and CDI-treatment costs refer only to the cost of pharmacologic therapy. Of note, patients hospitalized with spinal cord injury (SCI) at the time of CDI diagnosis were excluded from analyses given prolonged length of stay associated with SCI care, but these patients were included when accounting for total cases of HO-HCFA CDI, the total number of C. difficile NAAT ordered, and hospital census counts.

Statistical analysis

Differences in direct comparisons between normally distributed continuous variables were calculated using t tests, whereas ordinal and non–normally distributed continuous variables were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. For analysis of the aforementioned variables in comparisons across multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Kruskal-Wallis testing were used. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. A P value of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism 8 was used for all statistical analyses. Please see Supplementary Table 1 (online) for a comprehensive overview of comparative analyses performed.

Results

Risk factors

HO-HCFA CDI cases were noted to predominantly occur in patients with antibiotic exposure within 3 months (84%). Roughly one-quarter of cases (23%) involved patients with some form of immunosuppression, including those treated with exogenous corticosteroids, immunomodulators, biologics, or chemotherapy within the previous 3 months (Table 1). Other major risk factors noted among those with CDI include history of type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus (35%) and prior CDI (17%). No significant difference in the prevalence of cases involving subjects with prior CDI history, recent antibiotic exposure, immunosuppression or ICU admission at the time of CDI diagnosis for FY2015 versus FY2018, FY2016 versus FY2018, or FY2017 versus FY2018 were noted. Initiatives implemented as part of the antimicrobial stewardship program resulted in significantly decreased PPI use in FY2018 compared to FY2015, FY 2016, and FY2017 (P ≤ .05), and in a 20% reduction in fluoroquinolone use from FY2015 to FY2016.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Testing Characteristics of Patients With C. difficile Infection From FY2015 to FY2018

| Variable | FY2015 | FY2016 | FY2017 | FY2018 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median y (IQR) | 69 (61–78) | 69 (63–71) | 67 (62–74) | 71 (67–78) | .32 |

| Gender b | |||||

| Male | 42 (95.5) | 35 (97.2) | 32 (94.1) | 13 (100) | .92 |

| Female | 2 (4.5) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | .92 |

| Clinical characteristics b | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (38.6) | 11 (30.6) | 12 (35.3) | 5 (38.4) | .55 |

| End-stage renal disease | 4 (9.1) | 2 (5.6) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (7.6) | .46 |

| Prior C. difficile infection | 6 (13.6) | 8 (22.2) | 6 (17.6) | 2 (15.4) | .61 |

| Antibiotic use within 3 mo | 36 (81.8) | 31 (86.1) | 30 (88.2) | 10 (76.9) | .75 |

| Laxatives (initiation or escalation)c | 20 (45.5) | 14 (38.9) | 11 (32.3) | 4 (30.1) | .62 |

| Tube Feeds (initiation)c | 7 (15.9) | 1 (2.8) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (7.7) | .20 |

| Proton pump inhibitor use | 26 (59.1) | 21 (58.3) | 16 (47.1) | 1 (7.7) | .006 |

| Immunosuppressiond | 8 (18.2) | 7 (19.4) | 10 (29.4) | 4 (30.8) | .39 |

| Testing | |||||

| + C. difficile NAAT | 44 | 36 | 34 | 13 | <.001 |

| Total C. difficile NAAT performed | 459 | 188 | 130 | 124 | … |

| % of + C. difficile NAAT | 9.6 | 19.1 | 26.2 | 10.5 | … |

| % of C. difficile NAAT performede | 7.9 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | |

| Inpatient admissionsf | 5,840 (0.8) | 5,387 (0.7) | 5,651 (0.6) | 5,868 (0.2) | … |

Abbreviations: FY, fiscal year; IQR, interquartile range; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

ANOVA, χ2, or Fisher exact tests were used to analyze numeric variables and C. difficile cases identified before and after diagnostic stewardship intervention (FY2017 vs FY2018). P ≤ .05 was considered significant for all statistical tests.

Data are represented as no. (%) of positive C. difficile toxin B gene NAAT unless otherwise specified.

No. of patients identified to be on laxatives or tube feeds within 24–48 h of C. difficile NAAT.

Immunosuppression defined as any patient treated with systemic corticosteroids, immunomodulatory or biologic therapy, and/or chemotherapy within 3 months of C. difficile infection diagnosis.

Percentage of C. difficile NAAT performed is the total inpatient admissions divided by total C. difficile NAAT performed × 100.

Inpatient admissions are represented as total numbers of patients admitted per fiscal year to units where cases of hospital-onset, healthcare facility–associated C. difficile infection were identified and (%) of positive C. difficile toxin B gene NAAT.

CDI treatment

The proportion of patients receiving oral (PO) metronidazole vs PO vancomycin vs PO metronidazole + PO vancomycin as CDI treatment did not vary significantly between FY2015 versus FY2018, FY2016 versus FY2018, and FY2017 versus FY2018 (Supplementary Table 2 online). As anticipated, there was a non-significant trend toward greater use of PO vancomycin as the sole agent or in combination with PO metronidazole in FY2018 versus FY2015 (77% vs 59%) based on updates to the “Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA)” recommending PO vancomycin as first-line therapy.13 Of all HO-HCFA CDI cases identified, 22 of 127 (17%) were first or second recurrences. The proportion of cases that were first or second recurrences also did not vary significantly between FY2015 versus FY2018, FY2016 versus FY2018, or FY2017 versus FY2018. Of the recurrences, patients received PO vancomycin as part of their treatment in 16 (73%) cases. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) was used to treat only 1 case of HO-HCFA CDI identified during the study period. However, a total of 5 patients included in the study ultimately underwent FMT for recurrent or refractory CDI as of February 2020.

Laxatives and false-positive HO-HCFA CDI diagnoses

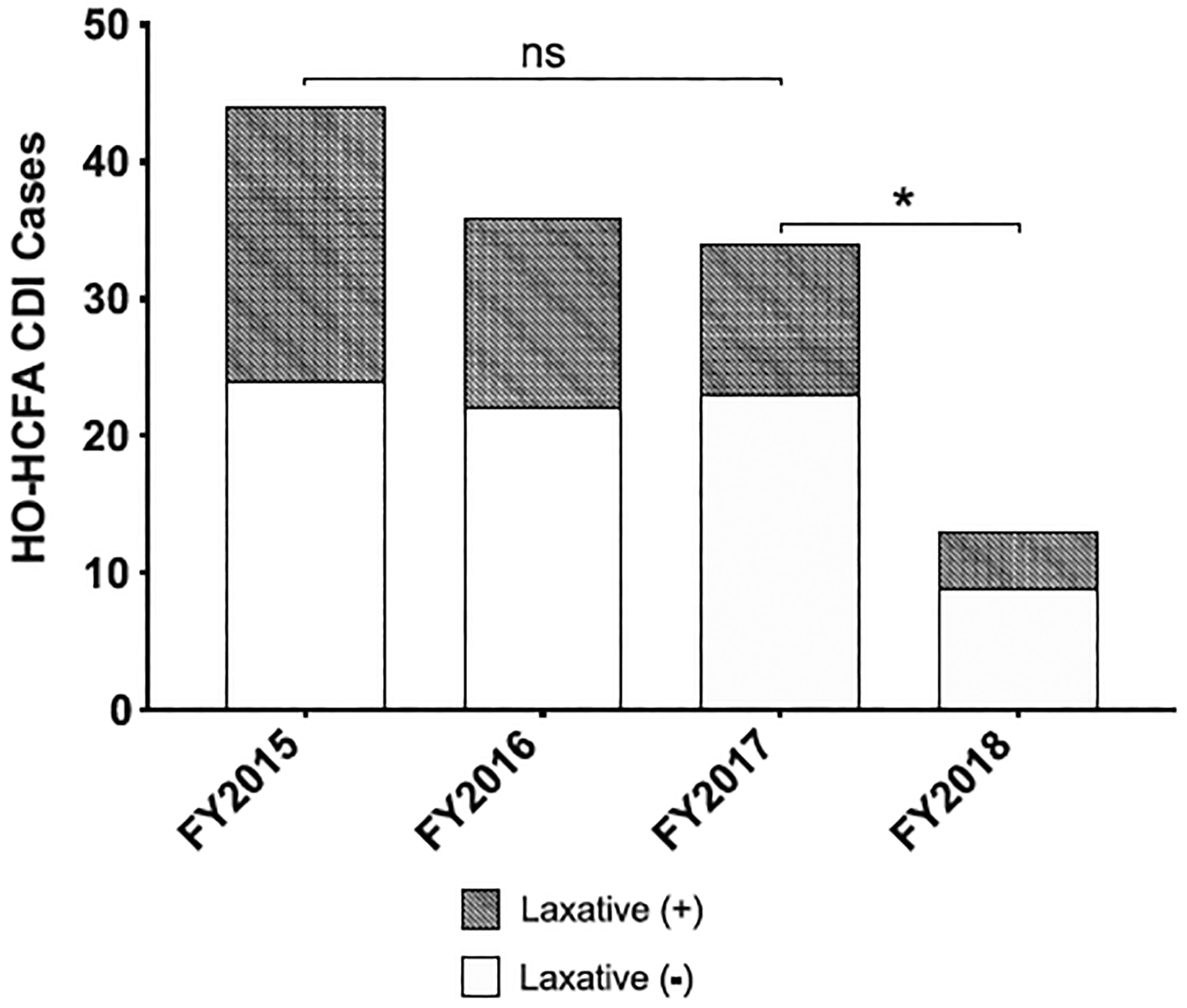

The number of presumed false-positive HO-HCFA CDI diagnoses associated with use or escalation of laxatives at the time of CDI stool NAAT (accounting for those on chronic laxatives) decreased across the study period and most dramatically from FY2017 versus FY2018 (11 vs 4) following institution of diagnostic stewardship with outlined testing criteria (Fig. 2). The most commonly prescribed laxatives were docusate and senna. There was no significant difference in the use of tube feeding within 48 hours of testing between FY2018 versus FY2017, FY2018 versus FY2016, or FY2018 versus FY2015 (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Number of diagnosed HO-HCFA CDI cases identified using stool C. difficile toxin B gene NAAT from FY 2015 to FY 2018 including false positives associated with the initiation or escalation of laxatives. *P ≤ .05 or NS, no statistical significance by Mann Whitney U test comparing the number of monthly HO-HCFA cases identified in FY2015 to FY2017 and FY2017 to FY2018 (pre and post diagnostic stewardship intervention). Abbreviations: HO-HCFA CDI = Healthcare Onset, Healthcare Facility Associated C. difficile Infection, FY = Fiscal Year, NAAT = Nucleic Acid Amplification Test.

Primary outcomes

From FY2015 to FY2018, a total of 127 cases of HO-HCFA CDI were identified (median age: 68 years; 96% male). Patient demo-graphics and comorbidities were similar across FYs (Table 1). The total number of CDI stool NAATs ordered for inpatients also decreased substantially from FY2015 to FY2018 (459 vs 124) but only slightly from FY2017 to FY2018 (130 vs 124). A significant decrease was observed in the number of HO-HCFA CDI cases (44 vs 13; P ≤ .05), total hospital days (905 vs 332), total CDI-related costs ($4,571,374 vs $1,534,190), and total CDI treatment cost ($10,379 vs $1,476) from FY2015 versus FY2018 following the execution of all CDI rate-reducing initiatives (Tables 1 and 2). The number of HO-HCFA CDI cases (34 vs 13; P ≤ .05), total hospital days (596 vs 332), total CDI-related costs ($2,780,681 vs $1,534,190), and total CDI treatment cost ($7,158 vs $1,476) were most notably reduced from FY2017 to FY2018, primarily following the implementation of the test-ordering algorithm (Tables 1 and 2). Overall, there was no significant difference in CDI severity (determined using IDSA and SHEA clinical practice guidelines) or those receiving ICU level of care between FY2016 versus FY2017 or FY2015 versus FY2017, respectively, but there was a trend toward lower proportions of severe and fulminant cases of CDI in FY2018 (42%) compared to FY2015 (61%), FY2016 (58%), and FY2017 (58%).

Table 2.

Cost of C. difficile Infection–Associated Hospitalization and Treatment From FY2015 to FY2018

| Variable | FY2015 | FY2016 | FY2017 | FY2018 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization | |||||

| Total days ± SD | 905 ± 24 | 428 ± 11 | 596 ± 11 | 332 ± 33 | … |

| Median length of stay, days (IQR) | 17 (12–26) | 10 (8–16) | 14.5 (10–22) | 19 (12–30) | .03 |

| ICU admission, no. (% positive) | 11 (25) | 3 (8.3) | 11 (32.3) | 2 (13.3) | .07 |

| Expenditures b | |||||

| Median hospitalization cost (IQR) | $74,815 ($50,168–115,872) | $34,670 ($25,547–55,655) | $80,854 ($39,232–112,170) | $69,341 ($41,969–171,939) | .001 |

| Total hospitalization cost ±SD | $4,571,374±$164,669 | $1,944,157±$84,420 | $2,780,681±$52,241 | $1,534,190±$144,755 | … |

| Median CDI treatment cost (IQR) | $257 ($123–309) | $184 ($105–285) | $184 ($79–282) | $101 ($50–167) | .03 |

| Total CDI treatment cost ± SD | $10,379 ± $162 | $7,562 ± $122 | $7,158 ± $204 | $1,476 ± $117 | … |

Abbreviations: FY, fiscal year; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; ICU, intensive care unit; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; FMT, fecal microbiota transplant; VASDHS, VA San Diego Healthcare System.

The χ2, Fisher exact or Mann-Whitney U tests were used to analyze numeric variables and C. difficile cases identified pre and post diagnostic stewardship intervention (FY2017 vs FY2018). P ≤ .05 was considered to be significant for all statistical tests.

All costs are represented as US dollars. Hospitalization costs (also referred to as C. difficile infection-related costs) were derived from total days or median length of stay and care provided in a general medicine ward or ICU for C. difficile infection and other comorbidities. Treatment costs were derived from current average wholesale prices of medications (vancomycin, metronidazole, and fidaxomicin) and documented durations of therapy. The cost of oral vancomycin was based on the cost per unit volume of intravenous vancomycin rather than the oral pulvule formulation to represent what is commonly used in practice at the VASDHS. The cost of IVIG and FMT used for a single patient in FY2015 and FY2016 respectively were considered outliers and therefore excluded.

Discussion

Improved diagnostic stewardship in conjunction with other measures to reduce risk for hospital-acquired infection (HAI) decreased the incidence of HO-HCFA CDI cases at our institution by ~70% (44 vs 13 cases; P ≤ .05) from FY2015 to FY2018 (Fig. 2). Interventions to reduce HAI risk included education campaigns to augment hand hygiene compliance, timely isolation of C. difficile positive patients, enhanced cleaning measures, and reduction of fluoroquinolone and PPI use (Fig. 1). Overall, these particular measures resulted in a 39% reduction in total CDI-related costs, a 31% reduction in total CDI treatment costs, and a 23% decrease in the incidence of HO-HCFA CDI cases (44 vs 34 cases; P = 0.31) from FY2015 to FY2017 (Table 2 and Fig. 2). However, the most profound decrement in HO-HCFA CDI cases was observed following the institution of diagnostic stewardship with a C. difficile test-ordering algorithm during FY2018. The use of diagnostic stewardship resulted in a 45% reduction in total CDI-related costs, a 79% reduction in total CDI treatment costs, and a 62% decrease in the incidence of HO-HCFA CDI cases (34 vs 13 cases; P ≤ .05) from FY2017 to FY2018 (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

NAAT alone cannot distinguish between disease and colonization.14–16 In addition to traditional interventions used to decrease C. difficile exposure and risk factors, our retrospective study highlights the effectiveness and use of diagnostic stewardship to mitigate the detection of potential false-positive results from C. difficile toxin B gene NAATs associated with colonization and laxative use. Such false-positive results lead to inaccurate diagnoses of HO-HCFA CDI, unnecessary treatment, and increased healthcare costs. The established diagnostic testing criteria utilized at VASDHS helped to ensure judicious ordering of C. difficile toxin B gene NAAT and avoidance among patients unlikely to have true CDI (eg, with <3 diarrheal episodes and/or laxative induced diarrhea). Furthermore, results from our investigation before and after the intervention suggest the use of NAAT for diagnosis of HO-HCFA CDI in the absence of diagnostic stewardship results in gross overestimation of disease burden (Fig. 2). These findings have been corroborated by others.17–19

The use of 2- or 3-step algorithmic testing (eg, glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH)) + toxin enzyme immunoassay (EIA), GDH + toxin EIA followed by confirmatory NAAT or NAAT + toxin EIA) rather than NAAT alone has been touted by European and IDSA/SHEA guidelines as a means to discern CDI from colonization and to improve sensitivity compared to toxin EIA alone.20,21 However, we have demonstrated that diagnostic stewardship and C. difficile toxin B gene NAAT, the most sensitive method to diagnose CDI, can be used in combination to effectively differentiate CDI from colonization.22,23 Furthermore, NAAT alone poses inherent advantages over multistep testing: reduced turn-around time (120 minutes for GDH + toxin EIA + NAAT vs 45 minutes for NAAT) resulting in rapid diagnosis and initiation of treatment, decreased cost ($70 per sample for GDH + toxin EIA + NAAT vs $50 per sample for NAAT), and decreased mean length of hospital stay (9.51 days for NAAT vs 10.27 days for multistep testing).24,25 Additionally, components of multistep testing, such as toxin EIA, have been associated with false-negative results due to toxin instability, rapid toxin degradation within 2 hours at room temperature, and variable toxin production depending on the bacterial phase of growth. Because of these deficiencies, reflex NAAT is needed to confirm the presence or absence of C. difficile.26–28

Limitations of our retrospective study were multi-fold including the quasi-experimental design, inability to perform a case control or randomized control study, assessment of interventions solely at a single center, potential misclassification of CDI as hospital onset instead of community onset based on NHSN laboratory event reporting (performed at ≥4 days of hospitalization) and not onset of symptoms, and inability to determine if patients prescribed home laxatives routinely utilized them at baseline or inadvertently developed laxative induced diarrhea upon hospitalization following scheduled administration. Other limitations likely affecting observed HO-HCFA CDI rates included concurrent education of medical staff on the diagnostic stewardship intervention, and physician, nursing and lab personnel non-adherent to recommended testing criteria and solid stool sample rejection. Furthermore, implementation of diagnostic stewardship overall resulted in only a 5% reduction in inpatient NAAT from FY2017 to FY2018 but could be attributed to the increased number of hospitalizations observed in FY2018 compared to FY2017 (Table 1). Regardless, our investigation strongly suggests intervention testing criteria resulted in more judicious testing given the dramatic reduction of positive HO-HCFA CDI cases associated with laxative use.

Other measures preceding the diagnostic stewardship intervention (eg, prompt isolation of CDI patients, enhanced cleaning measures and improved hand hygiene compliance, etc), may also have contributed to the decrease in absolute number of HO-HCFA CDI cases observed in FY2018 through a time lag effect. However, we were unable to retrospectively assess compliance or effectiveness of all interventions instituted, with the exception of the antibiotic and diagnostic stewardship measures (eg, fluoroquinolone and PPI use, testing criteria). We were also unable to ascertain potential adverse consequences associated with the diagnostic stewardship and recommended testing criteria (though there was no hard stop to prevent stool NAAT ordering and no colectomies or deaths were observed during the study period).

In conclusion, the multifaceted approach adopted at our facility resulted in reduced risk, C. difficile transmission, and misdiagnosis of CDI. The implementation of diagnostic stewardship with C. difficile toxin B NAAT criteria in particular had the greatest impact on decreasing HO-HCFA CDI rates. The benefits of diagnostic stewardship include judicious testing, reduced detection of C. difficile colonization associated with laxative use, decreased classification of HO CDI penalized by Medicare/Medicaid, savings in healthcare costs (decreased length of hospital stay, cost of CDI related hospitalization, cost of treatment, etc), appropriate use of isolation precautions for patients meeting testing criteria, and prevention of antibiotic resistance (eg, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus) and disruption of gut microbiota associated with unnecessary CDI treatment. Findings from our investigation support the use of diagnostic stewardship with testing criteria among facilities solely utilizing stool NAAT to accurately identify cases of CDI, reduce HO-HCFA CDI rates (ie, detection of potential false positives), and to prevent unnecessary treatment and healthcare dollar expenditures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are profoundly grateful to former members of the VA San Diego Healthcare System Infection Prevention and Control Program (William Cardona, RN; Ashley Eischeid, NP; and Deborah Haist, RN) who played key roles in the C. difficile quality improvement project.

Financial support.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (grant no. 1KL2TR001444 to M.K.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest. S.M. has received consulting fees from Medial EarlySign. All other authors reported no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material. To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.375

References

- 1.Lyerly DM, Krivan HC, Wilkins TD. Clostridium difficile: its disease and toxins. Clin Microbiol Rev 1988;1:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubberke ER, Olsen MA. Burden of Clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55 suppl 2:S88–S92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1198–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guh AY, Mu Y, Winston LG, et al. Trends in US burden of Clostridioides difficile infection and outcomes. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1320–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polage CR, Gyorke CE, Kennedy MA, et al. Overdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection in the molecular test era. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1792–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med 2000;342:390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 1989;320:204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riggs MM, Sethi AK, Zabarsky TF, Eckstein EC, Jump RL, Donskey CJ. Asymptomatic carriers are a potential source for transmission of epidemic and nonepidemic Clostridium difficile strains among long-term care facility residents. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:992–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckel WR, Avdic E, Carroll KC, Gunaseelan V, Hadhazy E, Cosgrove SE. Gut check: Clostridium difficile testing and treatment in the molecular testing era. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;36:217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubberke ER, Han Z, Bobo L, et al. Impact of clinical symptoms on interpretation of diagnostic assays for Clostridium difficile infections. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:2887–2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peasah SK, McKay NL, Harman JS, Al-Amin M, Cook RL. Medicare non-payment of hospital-acquired infections: infection rates three years post implementation. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev 2013;3.doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.03.a08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Healthcare Safety Network. Multidrug-resistant organism and Clostridioides difficile infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/faqs/faq-mdro-cdi.html. Published 2019, Accessed August 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:e1–e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang FC, Polage CR, Wilcox MH. Point–counterpoint: what is the optimal approach for detection of Clostridium difficile infection? J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:670–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Planche TD, Davies KA, Coen PG, et al. Differences in outcome according to Clostridium difficile testing method: a prospective multicentre diagnostic validation study of C. difficile infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:936–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapin KC, Dickenson RA, Wu F, Andrea SB. Comparison of five assays for detection of Clostridium difficile toxin. J Mol Diagn 2011;13:395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truong CY, Gombar S, Wilson R, et al. Real-time electronic tracking of diarrheal episodes and laxative therapy enables verification of Clostridium difficile clinical testing criteria and reduction of Clostridium difficile infection rates. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:1276–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bilinskaya A, Goodlet KJ, Nailor MD. Evaluation of a best practice alert to reduce unnecessary Clostridium difficile testing following receipt of a laxative. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;92:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christensen AB, Barr VO, Martin DW, et al. Diagnostic stewardship of C. difficile testing: a quasi-experimental antimicrobial stewardship study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2019;40:269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crobach MJ, Planche T, Eckert C, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the diagnostic guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22 suppl 4:S63–S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longtin Y, Trottier S, Brochu G, et al. Impact of the type of diagnostic assay on Clostridium difficile infection and complication rates in a mandatory reporting program. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Berg RJ, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet LS, Gerritsen HJ, Endtz HP, van der Vorm ER, Kuijper EJ. Prospective multicenter evaluation of a new immunoassay and real-time PCR for rapid diagnosis of Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:5338–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon HW, Kim HN, Hur M, Shim HS, Kim H, Yun YM. Comparison of diagnostic algorithms for detecting toxigenic Clostridium difficile in routine practice at a tertiary referral hospital in Korea. PLoS One 2016;11: e0161139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engstron-Melnyk JA LC, Li Y-C, et al. Diagnostic testing choice impacts hospital length of stay for patients diagnosed with C. difficile infections—real-world evidence from the US ASM Microbe; 2019; San Francisco, California. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2002;346:334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hundsberger T, Braun V, Weidmann M, Leukel P, Sauerborn M, von Eichel-Streiber C. Transcription analysis of the genes tcdA-E of the pathogenicity locus of Clostridium difficile. Eur J Biochem 1997;244: 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clostridioides difficile. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/index.html. Accessed August 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.