Abstract

Guided by a convoy model of social relations, this study explores the complex relationships between loneliness, age at immigration, familial relationships, and depressive symptoms among older immigrants. This study used 2010 Health and Retirement Study data from a sample of 575 immigrants (52% female, age range 65–99 years). Ordinary least squares regression models were estimated. The findings indicate that for older immigrants who came to the United States at age 45 or older, loneliness was significantly positively associated with depressive symptoms. Further, perceived negative strain and hours spent helping family moderated this relationship such that the effect of loneliness on depressive symptoms was stronger among respondents who perceived more negative family strain and spent fewer hours helping family. Familial relationships are crucial for the psychological well-being of older immigrants because they can be a source of either stress or support. The results have implications for how research and practices can support the immigrant families.

Keywords: Migration, loneliness, depression, family relationships, age at immigration

Introduction

Loneliness is a growing social problem that increases the risk of serious medical conditions among older adults in the United States. According to a recent report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), more than one-third of adults age 45 and older feel lonely, and nearly one-fourth of adults age 65 and older are considered socially isolated (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020). Older immigrants are one of the most vulnerable populations in the United States, and among this group, late-life immigrants1, in particular, are often at risk of isolation due to language barriers, small social networks, and cultural differences between their country of origin and their new home country (Emami, Toress, Lipson, & Ekman, 2000). Further, this population is growing rapidly, and thus deserves more scholarly attention. Between 2000 and 2017, the percentage of newly arrived immigrants who were age 50 and older nearly doubled, increasing from 8% (120,000) to 15% (276,000), while the share age 65 and older roughly tripled, rising from 2% (37,000) to 6% (113,000) (Camarota & Zeigler, 2019). Because the average age of immigrants arriving in the United States has increased in recent years and because relocation intensifies the issues facing older individuals, more research is needed to better understand the association between loneliness and well-being among older immigrants.

As a result of the stress associated with immigration and acculturation, immigrants are at a higher risk of experiencing depressive symptoms than their native-born counterparts (Wilmoth & Chen, 2003). Loneliness, which is a risk factor for depressive symptoms (Cacioppo et al., 2010), may be one of the factors driving this increased risk. Further, immigrants who arrive later in life may experience higher levels of loneliness than those who arrive at younger ages, because of pressures such as insertion into a new and unfamiliar environment, which increases both loneliness and the risk of depression (Angel et al., 2001). Relationships with family also likely play an important role in the experiences and well-being. A growing body of research has found that supportive familial relationships reduce loneliness and depressive symptoms (Wu & Penning, 2015). In recent years, family unification—or joining family members who arrived earlier—has been an important way that older immigrants are admitted to the United States (Carr & Tienda, 2013), and thus relationships with family members have particularly serious implications for the well-being of this group.

While extant research clearly suggests there is a complex relationship between loneliness, age at immigration, family relationships, and depression, few studies have examined the intricate associations between these four variables. To address this gap in the literature, this study utilizes data from a large nationally representative sample to examine (1) whether loneliness is associated with depressive symptoms, and (2) whether the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms differs by age at immigration and family relationships among older immigrants.

Literature review

Loneliness, age at immigration, and depressive symptoms

Immigration is a stressful life event, and immigrants commonly experience loneliness—defined as an unpleasant feeling or dissatisfaction that arises when one’s network of social relations is considered deficient in quantity or quality (Perlman, 2004)—during the transition from home country to host country due to the stress associated with immigration as well as the lack of coping resources available (Wu & Penning, 2015). Growing older can create a “double jeopardy” situation for older immigrants because they face the usual challenges associated with aging as well as challenges related to immigration, and both experiences are associated with increased loneliness.

The difficulties and stresses immigrants experience when they move to a new country vary by age at immigration (Jasso, 2003). International migration is an important turning point in the life course and often leads to long-term changes in individual-level trajectories in various domains, such as health, economic well-being, family, and social life (Guo et al., 2021). Wu and Penning (2015) found that those who immigrated later in the life course experienced greater loneliness than those who immigrated earlier. Because immigrating later in life may entail greater difficulties (including a lack of opportunities), the former group may have problems integrating and developing close personal attachments as they age. In addition, Wu and Penning (2015) found that those who immigrated during childhood did not differ from their native-born counterparts in the host country with respect to several cultural characteristics. Prior research has identified specific challenges that affect immigrants’ mental health including communication difficulties due to language and cultural differences; differences in family structure and processes affecting adaptation, acculturation, and intergenerational conflict; and aspects of acceptance by the receiving society that affect employment, social status, and integration (Kirmayer et al., 2011; Leu et al., 2008; Ponizovsky & Ritsner, 2004).

The experience of loneliness is important because it is a leading cause of depressive symptoms among older adults (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001). Experiences of change, loss, perceived discrimination, and social marginalization are associated with depressive symptoms (Saraga & Gholam-Rezaee, 2013), which are associated with negative consequences including decreased physical, mental, and social function, and greater morbidity (Fiske et al., 2009).

The role of family relationships

Not all lonely individuals report increased depressive symptoms. Certain factors may help preventing loneliness from developing into depressive symptoms. The extant research shows that family members foster older immigrant’s psychological well-being by providing a system of social support, developing a sense of cohesion, and transmitting cultural values (Ward et al., 2010), even if, as Treas (2008) suggested, the belief that the warm embrace of family life affords special protection to older immigrants is a myth, and cultural expectations for family togetherness are difficult to achieve in U.S. society. Further, Treas (2008) stated that family is key to the survival and success of older immigrants in the United States as these immigrants are intrinsically linked with their families because of cultural preferences, economic difficulties, language barriers, and the availability of entitlement programs. Positive family relationships may facilitate an older immigrant’s use of health care by providing health care information, bridging language/cultural gaps, and providing assistance such as financial support and transportation (Pang et al., 2003).

Guo and colleagues (2019) posited that adaption upon immigration is particularly important for late-life immigrants, who may find acculturation challenging because they have had longer exposure to the heritage culture, which usually has a greater focus on familial relations. Because those who immigrated in late life often do so to reunite with family members, disruptions in family relations may increase their need for formal support (Guo et al., 2019). Thus, Rote and Markides (2014) stressed the importance of close family networks that can serve as the foundation for a supportive exchange process for many older immigrants who lack access to aspects of the United States’ social safety net. Indeed, a majority of older immigrants live with other family members for financial and sociocultural reasons (Angel et al., 2000).

The convoy model of social relations is beneficial to the design of a study seeking to reduce loneliness among older adults by taking a comprehensive approach to understanding availability of social relations (Fuller et al., 2020). The model posits that people differentiate their relationships hierarchically, from very close to much less close, that most people consider their relationships with family members to be their closest relationships and that these close relationships are important for social support (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). Close relationships are strongly associated with increased well-being, and thus can be an important buffer against the negative consequences of loneliness (Ajrouch, 2008).

Primary convoy members are often spouses/partners, children, parents, and siblings with whom the individual feels very close and exchanges many types of support (Ajrouch et al., 2005). The convoy model further postulates that relationships vary in structure (e.g., size, composition, contact frequency, geographic proximity), closeness and quality (e.g., positive, negative), and function (e.g., aid, affection, affirmation exchanges) (Antonucci et al., 2011). Each aspect of social relationships—social networks (e.g., frequent family contact, number of close family members), relationship quality (e.g., perceived positive support, perceived negative strain), and social support (e.g., instrumental support [hours of helping family])—influence both how much stress a person will experience and how negatively or positively they will be affected by this stress (Antonucci et al., 2011). Empirical evidence has shown that frequent contact, a high level of perceived closeness, and frequent exchange of emotional and instrumental support through family relationships are positively associated with individuals’ psychological well-being (Fingerman et al., 2013).

Moderating effects of age at immigration and family relationships

Loneliness is also associated with a variety of interpersonal problems such as low communication competence (Zakahi & Duran, 1985) and minimal availability of social support (Bell & Gonzalez, 1988). The difficulties in immigration may push older immigrants feel lonely and isolate them from the mainstream society, as well as from their family (Hossen, 2012). Research has found that individuals who feel lonely and those who experience strain in their relationships are more likely to develop depressive symptoms (Chen & Feeley, 2014). Over time, aging immigrant family members might become less likely to endorse traditional family structures and more likely to embrace forms of family adaption common in the United States (Singh & Siahpush, 2001). For older immigrants who have few social ties outside their families, frequent contact between family members may increase closeness and relationship quality (Lawton et al., 1994). However, in a qualitative research with 28 Latina immigrants, Hurtado-de-Mendoza and colleagues (2014) found that having close family members in the United States did not readily translate into having available sources of support, which exacerbated perceptions of loneliness.

Even though many older immigrants live with their families, they are often dissatisfied with the level of companionship and social interaction that their families provide (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Tensions between family members may greatly aggravate older immigrants’ health if they focus narrowly on familial relationships because they have a limited social network. Further, prior research has shown that receiving assistance is associated with more depressive symptoms, whereas giving assistance is negatively related to depressive symptoms (Liang, Krause, & Bennett, 2001). Thus, researchers should pay more attention to the types of support and help that older immigrants provide to their family members because providing such help may be burdensome, stressful, and demanding, but may also instill a sense of duty and promote feelings of reciprocity between family members (Rote & Markides, 2014).

Although both theoretical and empirical evidence suggest that age at immigration may affect the relationship between loneliness and depressive symptoms, the literature is small and the findings are mixed. Given the importance of familial relationships for older immigrants, and the potential for these relationships to influence well-being, a more nuanced understanding of this topic is needed. Thus, building on prior work, the current study evaluates two hypotheses: (1) loneliness is positively associated with increased depressive symptoms among older immigrants, and (2) the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms is stronger (a) for those who immigrated in later life than those who immigrated earlier and (b) for those with poorer family relationships (low contact frequency with family/perceived negative strain/fewer hours spent helping family) than those with better family relationships.

Method

Data and sample

The data were drawn from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The HRS sample is a nationally representative sample of the population aged 51 years and older, living private households in the United States. This study used 2010 RAND HRS data merged with RAND HRS family data. Since 2006, HRS has included questionnaires about psychosocial well-being and social context. In 2010, 50% of HRS respondents were randomly selected to participate in a face-to-face interview; the remaining 50% of respondents were invited to participate over next 2 years. Among those who were interviewed, the response rate for the leave-behind questionnaire was 90%, and the focal sample is limited to respondents who completed the psychosocial questionnaire. The final sample includes 575 older immigrants aged 65 and older (52% female) with a mean age of 77.96 years (SD = 8.25, range 65–99). The majority were White (51.6%) and Hispanic (33.4%), with 5.5% African American and other (9.5%). On average, participants had completed 12.28 years of formal education (SD = 3.17), and 49.6% (n = 285) were married or had a partner. Participants experienced on average .76 functional limitations (SD = 1.37) and 2.54 chronic conditions (SD= 1.35).

Measures

Depressive symptoms.

The HRS measures depressive symptoms via a subset of eight items from the standard Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression scale (CES-D). Respondents were asked about their depressive affect (e.g., I felt depressed), well-being (e.g., I was happy), and somatic symptoms (e.g., I could not get going). Participants responded yes or no to items asking whether they experienced each of eight symptoms much of the time in the past week. A summary score was created by summing affirmative responses (range: 0–8; Cronbach’s α =.77).

Loneliness.

A shortened version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004) was used. The four items included were: How often do you feel that you lack companionship; are left out; are isolated from others; and are alone? Responses were coded from 1 (hardly ever or never) to 3 (often) so that a higher value indicates a higher level of loneliness. The reliability of this measurement is α = .85

Age at immigration.

Age at immigration was based on the respondent’s report of the year they arrived in the United States. For each respondent, birth year was subtracted from the year of arrival; respondents were then grouped into three categories: immigrated before age 19, immigrated at age 19–44, and immigrated at age 45 or older. This study used age 45 as the lower threshold for immigrating during late-life. Given recent increases in longevity, this threshold may be somewhat younger than those used for late-life immigration in other studies (Jang, Pilkauskas, and Tang, 2020; see the “Limitations and Implications” section for further discussion of this issue).

Frequency of contact with family.

Participants were asked how frequently they had contact with their children and other family members who were not living with them. Frequency of contact was measured via three questions: How often do you meet up/speak on the phone/write or email with your children and other family? For each question, scores ranged from 1 (less than once a year or never) to 6 (three or more times a week). Scores were summed and averaged (range: 1–6).

Number of close family members.

Participants reported how many close relationships they had with children and with other family members. Scores for the two items were summed. To deal with extreme values, the variable was top-coded at the 95th percentile of the distribution (15 close family members).

Perceived positive support and negative strain.

Participants rated the positive and negative aspects of their relationships with their spouse (partner), children, and other family members on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot). Perceived positive relationship quality included three items: How much do they understand the way you feel about things? How much can you rely on them if you have a serious problem? How much can you open up to them if you need to talk about your worries? Negative relationship strain included four items: How often do they make too many demands on you; criticize you; let you down when you are counting on them; get on your nerves? Indices of positive social support (Cronbach’s α=.82) and negative social strain (Cronbach’s α= .82) were created by summing and averaging the scores.

Hours spent helping family.

This variable was based on three items from the RAND HRS family data that asked respondents how many hours per month they spent helping their children and doing errands for their parents and parents-in-law. Unfortunately, the HRS did not ask how many hours respondents spent helping or providing emotional support to other family members (e.g., siblings). To deal with extreme values, the variable was top-coded at the 95th percentile of the distribution (100 hours).

Covariates.

Sociodemographic characteristics including age (years), gender (male, female), race (White, Black, Hispanic, other), marital status (not married, married), functional limitations (number of IADL), and education (years) were included as covariates. Chronic health conditions were measured as diagnoses of diabetes, cancer, coronary heart disease, stroke, and psychiatric distress (except depression). Each disease diagnosis was measured as a dichotomous variable (0 = no, 1 = yes) and the final variable was the sum of positive responses (range: 0–7). Lastly, living arrangement was added as a covariate (0 = not living with children, 1 = living with children).

Analytic strategy

Unweighted descriptive statistics were calculated. We then conducted multivariate regression models examining the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms. Age at immigration and the indicators of family relationship (social network, relationship quality, and social support) were then added to the model. Finally, to test the second hypothesis, interaction terms between loneliness and age at immigration and each indicator of family relationships were added to the regression models. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata 14. In addition, multiple imputation was conducted using the Stata imputation by chained equations procedure, generating 20 imputed datasets to deal with missing cases (Royston, 2004).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the key variables. On average, respondents reported that they were lonely some of the time in the past week (M = 1.49, SD = .55). Approximately 17% of respondents immigrated before age 19 (n = 99), 71% (n = 406) immigrated at ages 19–44, and 12% (n = 70) immigrated after age 44. On average, respondents contacted their family more than once every few months (M = 3.58, SD = .96), and had six close family members (M = 6.39, SD = 3.74). In addition, respondents reported that, on average, their families offered “somewhat” positive support (M = 3.26, SD = .71) and they experienced “little” negative strain with their family (M= 1.54, SD= .65). In terms of instrumental support, respondents spent an average of 18 hours supporting family members each month (M = 7.18, SD = 22.91). Table 2 shows the correlations between variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of key variables (N = 575).

| Variables | n/Mean (SD) | %/Range |

|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | 1.49 (.55) | 1–3 |

| Age at immigration | ||

| Immigration at age <19 | 99 | 17.2% |

| Immigration at age 19–44 | 406 | 70.6% |

| Immigration at age 45 or older | 70 | 12.2% |

| Frequency of family contact | 3.58 (.96) | 1–6 |

| Number of close family | 6.39 (3.74) | 0–15 |

| Perceived positive support | 3.26 (.71) | 1–4 |

| Perceived negative strain | 1.54 (.65) | 1–4 |

| Hours of helping family | 7.18 (22.91) | 0–100 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.50 (1.89) | 0–8 |

| Age | 77.96 (8.25) | 65–99 |

| Female | 300 | 52.2% |

| Race | ||

| White | 297 | 51.6% |

| African American | 32 | 5.5% |

| Hispanic | 192 | 33.4% |

| Other | 54 | 9.5% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 285 | 49.6% |

| Not married | 290 | 50.4% |

| Education (years) | 12.28 (3.17) | 0–17 |

| Income | 55,287.84 (86,796.54) | 0–850,580 |

| Living with children | 12.28 (3.17) | 0–17 |

| Chronic conditions | 2.54 (1.35) | 0–7 |

| Functional limitations | .76 (1.37) | 0–5 |

Note. Descriptive statistics are reported prior to imputation.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients among continuous variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive symptoms | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 2. Education (in years) | −.191*** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 3. Income | −.112 | −.024 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 4. Chronic conditions | .219*** | −.054 | −.031 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 5. Functional limitations | .219*** | −.163*** | −.044 | .281*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 6. Loneliness | .283*** | −.134 | −.039 | .072 | .216*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 7. Frequency of family contact | −.150** | .223*** | −.082 | −.054 | −.271*** | −.268*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 8. Close number of family | −.132* | −.104* | −.051 | −.029 | −.068 | −.265*** | .322*** | 1.000 | |||

| 9. Perceived positive support | −.074 | −.057 | −.011 | −.081 | −.114* | −.304*** | .411*** | .371*** | 1.000 | ||

| 10. Perceived negative strain | .178*** | −.015 | .060 | .0378 | .077 | .296*** | −.104* | −.211*** | −.314*** | 1.000 | |

| 11. Hours spent helping family | .069 | −.056 | −.072 | .056 | .286*** | .010 | .003 | .030 | .040 | −.036 | 1.000 |

Note. Significance levels are denoted as

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Table 3 presents the unstandardized coefficients for the effects of loneliness, age at immigration, and familial relationships on depressive symptoms. Controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, health, and living with children, respondents who experienced more loneliness reported significantly more depressive symptoms (b =.01, p < .001). Respondents who came to the United States after age 44 (b = .62, p < .05) had significantly more depressive symptoms than those who came to the United States during childhood. In addition, each of the social relationship components—frequency of contact with family (b = −.04, p < .05), perceived positive support (b = −.03, p < .05), and perceived negative strain (b = .02, p < .05)—were significantly associated with depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Main effects of loneliness on depressive symptoms (N = 575).

| Depressive symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Loneliness | .01 (.02)*** | .07 (.02)*** | .14 (.04)*** | .45 (.14)** | .55 (.13)*** |

| Age at immigration | |||||

| Immigration at age 19–44a | .25 (.21) | .29 (.20) | .28 (.20) | .30 (.20) | |

| Immigration at age 45 or oldera | .62 (.30)* | .62 (.29)* | .59 (.29)* | .59 (.29)* | |

| Social network | |||||

| Frequency of contact with family | −.04 (.02)* | ||||

| Number of close family | −.04 (.10)* | ||||

| Relationship quality | |||||

| Perceived positive support | −.03 (.02)* | ||||

| Perceived negative strain | .02 (.02)* | ||||

| Social support | |||||

| Hours of helping family | .04 (.06) | ||||

| Age | −.02 (.01) | −.02 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) |

| Female | .19 (.15) | .18 (.16) | .17 (.14) | .18 (.15) | .01 (.07) |

| Married | −.32 (.17)* | −.27 (.17) | −.30 (.16)† | −.33 (.16)* | −.30 (.16)† |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: White) | |||||

| Black | −.05 (.26) | −.16 (.28) | −.13 (.27) | −.11 (.26) | −.14 (.27) |

| Hispanic | .25 (.17) | .24 (.18) | .21 (.19) | .24 (.17) | .22 (.17) |

| Other | .24 (.26) | .18 (.28) | .13 (.27) | .15 (.27) | .12 (.27) |

| Education (years) | −.09 (.03)*** | −.10 (.02)*** | −.09 (.02)*** | −.09 (.02)*** | −.08 (.02)*** |

| Income (logged) | −.02 (.04) | −.02 (.05) | −.01 (.04) | −.01 (.04) | −.01 (.05) |

| Living with children | .09 (.21) | −.17 (.20) | .09 (.21) | .08 (.20) | .06 (.21) |

| Chronic conditions | .24 (.05)*** | .24 (.06)*** | .25 (.05)*** | .24 (.10)*** | .25 (.05)*** |

| Functional limitations | .00 (.06) | .00 (.06) | .02 (.06) | .02 (.06) | .01 (.07) |

| _Constant | 1.99 (1.11)* | 2.07 (1.18)* | 2.35 (1.14)* | 2.38 (1.21)* | 2.01 (1.11)* |

Notes.

Reference group was immigration at age <19. Significance levels are denoted as

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

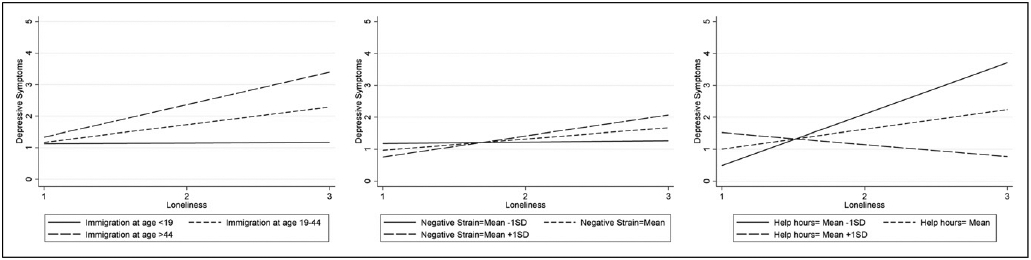

Table 4 displays the moderation effects of age at immigration and family relationships (social network, relationship quality, and social support) on the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms. The results show that among older immigrants, those who came to the United States at age 45 or older were more likely than those who came before age 19 to report higher levels of loneliness, which was positively associated with depressive symptoms (b = .12, p < .05). Figure 1 is a graphical representation of these associations. The results also suggest that both perceived negative strain and hours spent helping family moderate the relationship between loneliness and depressive symptoms. Perceived negative strain was a significant predictor of a higher level of depressive symptoms (b = .01, p < .05; see Figure 1). Thus, loneliness led to larger increases in depressive symptoms among respondents who reported more perceived negative strain. In addition, there was evidence that hours spent helping family buffered the effect of loneliness on depressive symptoms (b = −.04, p < .01; see Figure 1).

Table 4.

Interaction effects between loneliness, age at immigration, and social relationships.

| 95% CI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | Lower | Upper | |

| Loneliness × Immigration at age 19–44a | .07 (.05) | −.02 | .16 |

| Loneliness × Immigration at age 45 or oldera | .12 (.06)* | .00 | .23 |

| Loneliness × Frequency of family contact | .01 (.02) | −.02 | .05 |

| Loneliness × Number of close family | .03 (.04) | −.06 | .11 |

| Loneliness × Perceived positive support | .01 (.00) | −.00 | .01 |

| Loneliness × Perceived negative strain | .01 (.00)* | .00 | .02 |

| Loneliness × Hours of helping family | −.04 (.01)** | −.06 | −.02 |

Notes. CI: confidence interval.

Reference group was immigration at age <19. Covariates (age, gender, race, education, marital status, living with children, chronic conditions, and functional limitations) were controlled in each analysis. Significance levels are denoted as

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Figure 1.

Interacting effect of loneliness and age at immigration/family relationships (perceived negative strain and hours of helping family) on depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The current study examined how age at immigration and family relationships influence the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among older immigrants. Prior studies have shown that positive family ties have important implications for the well-being of older immigrants. Although loneliness in late-life is a widespread concern, researchers have not developed a nuanced understanding of how family relations influence the effect of loneliness on depressive symptoms among older immigrants. The current results indicate that age at immigration and family relationships can matter in such associations.

Loneliness and depressive symptoms by age at immigration

Among older immigrants, loneliness was more strongly associated with depressive symptoms for those who arrived in the United States at age 45 or older than for those who arrived at younger ages. Because the former group arrived relatively recently, it is likely still difficult for them to adapt to the host country, including adopting the language and culture, which reinforces their sense of loneliness (Maiter, 2003). Prior research has shown that being a late-life immigrant has a significant impact on social networks, intergenerational relationships, social relationships, and the separations that are part of living as a transitional family (Park & Kim, 2013). For older immigrants who grew up in a country in which family loyalty was a central value and age was accorded respect and associated with wisdom, the new culture, in which older adults are not respected and are dismissed as old fashioned, may be stressful. As a result, intergenerational relationships often become complex and difficult. Parents and children are part of an ever-changing convoys of social support (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980), whose members must be resocialized as they encounter new circumstances and as their relative resources, power, authority, and exchange patterns change over time (Swartz, 2009). Families can be a source of both stress and support during this process (Aroian et al., 1996).

The role of family relationships

Aspects of relationship quality (perceived negative strain) and social support (hours spent helping family) moderated the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms. The results highlight the importance of family relationships as part of the context in which older immigrants develop, which is consistent with previous studies showing that unfulfilled expectations and related dissatisfaction with family members were strongly associated with loneliness (Routasalo, Savikko, Tilvis, Standberg, & Pitkala, 2006). Although most older immigrants move to the United States to be close to their children or other family members, being dependent on family may threaten familial relationships and increase disconnection. Older immigrants’ dependence on family often leads to conflict, especially with respect to filial expectations for marred children (Kim et al., 1991). Families seem to sometimes fold in on older adults, simultaneously ignoring, indulging, and isolating them (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002).

As a result, the immigration experience shifts the interpersonal dynamics of immigrant families away from the family dynamics in the country of origin (Hossen, 2012). In relationships between parents and adult children, intergenerational conflict may arise when parents and their children do not share similar values, norms, lifestyles, and role expectations after arrival in the United States. In many cases, conflict evolves as the result of an older immigrant’s belief that younger family members should adhere to traditional filial piety in the form of caring for and respecting older adults, being deferential, and practicing absolute obedience (Hossen, 2012). The significant influence of the host culture frequently erodes the traditional norm of filial piety and creates generation gaps in everyday practices (Park & Kim, 2013). While these shifts are an example of normal generational conflict over values, those in the parent generation may perceive such changes as a threat to family solidarity, thus straining the relationship (Kalmijn, 2017). Consistent with the results of a previous study, experiencing a new culture may increase depressive symptoms, especially among older immigrants, because this transition forces individuals to negotiate two potentially conflicting identities and integrate into a society that can be hostile to minorities (Marsiglia et al., 2013).

Further, this study found a significant moderation effect of time spent helping family. Providing support to family members may predict a lower level of depressive symptoms with decreased loneliness. Older immigrants may feel obligated to help their adult children with childcare as they seek to cope with a variety of post-immigration challenges, including finances, employment, and career development (Chen et al., 2011). Prior studies also have found that providing childcare for grandchildren was associated with reduced depressive symptoms (Jang et al., 2020). However, demanding intergenerational relationships can lead to more depressive symptoms (Liu et al., 2017). Future research should examine the impacts of various forms of familial support on psychological well-being among older immigrants.

Although no other aspects of familial relationships moderated in the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms, the frequency of family contact had a statistically significant negative association with depressive symptoms. This result aligns with prior research showing that maintaining regular contact with close family members reduces depressive symptoms by increasing feelings of closeness and perceptions of a good relationship (Lawton et al., 1994). However, earlier research has found that frequent contact provides not only opportunities to share interests and opinions, but also a chance to fight and disagree (Van Gaalen et al., 2010). Further, relationships with family might be strong even when older immigrants have limited contact with family members (Kalmijn & Dykstra, 2006). Although frequency of contact with family was significantly inversely associated with depressive symptoms, the interaction term for loneliness and frequency of contact was not significant. The lack of a significant relationship between loneliness and family contact may be the result of ambivalence in family relationships and incongruities between relationship standards and experiences for immigrants who value filial piety (De Jong Gierveld et al., 2015).

Limitations

The analysis has several limitations. First, given this upper-limit on the age of respondents in the late-life immigrant group, this study reduced the lower age threshold for late-life immigration to age 45 to ensure a sufficient sample size. To account for current longevity trends, future studies should explore these associations among immigrants who arrived in the United States after age 60 or older. Further, in the current study, age at immigration was treated as a categorical variable because the distribution was skewed; however, prior research has suggested the value of including age as a continuous moderator using Local Structural Equation Modeling to flesh out moderation effects (Olaru et al., 2019). Second, an individual’s reasons for immigrating may have important effects on loneliness because voluntary and non-voluntary immigrants might perceive loneliness differently. Researchers have widely examined push/pull factors as determinants of immigration. Push factors include unsatisfactory conditions, such as political instability or heavy taxation, in the sending country, while pull factors are favorable conditions, such as a less polluted environment or a high-quality health care system, in the receiving country. Future research should assess how the reason for immigrating influences the relationship between loneliness and mental health. In addition, the limited number of immigrants in the sample meant it was not feasible to examine differences by country of origin or citizenship status (documented/undocumented) or cultural differences. Future research that can examine cross-country differences and incorporate English-speaking ability would be a useful extension.

Other factors that have a strong impact on loneliness, such as marital status and gender, should also be examined. For example, being married offers substantial protection against loneliness (Gierveld et al., 2015). Finally, individuals’ experiences may differ by length of residence in the United States even if they immigrated at the same age (or in the same age range). Some of the late-life immigrants in the current sample have lived in the United States for several decades already (e.g., an individual who immigrated to the United States at age 65 and is now age 90) while others have lived in the United States for a much shorter time (e.g., an individual who immigrated to the United States at age 65 and is now 70), and the experiences of these two groups might vary. Previous research has found that the longer immigrants spend in the host country, the more likely they are to acquire language skills and adopt the norms and behaviors of the host country, and the less likely they are to participate in immigrant-based cultural activities (Singh & Siahpush, 2001). Future research should consider the impact of length of residence on mental health among older immigrants.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study has important implications for research and practice. When older immigrants come to a new country, many experience loneliness, which increases the risk of mental health problems. Older immigrants may become more vulnerable to loneliness when they experience familial conflict, which often occurs when differences in cultural values between the origin culture and the receiving culture are replicated within the family. As Sluzki (1992) suggested, throughout the process of relocation, the emotional needs of individuals increase, while their social networks are severely disrupted. This is especially true for recent older immigrants; thus, researchers should study the effects of international relocation on mental health by analyzing personal social networks and family dynamics.

Further, as Guo et al. (2017) suggested, older immigrants with more coping resources (e.g., individual resources or support from family and friends) and favorable appraisals (e.g., sense of mastery) may experience less tense or conflictual relations in their families. Supportive family members and a strong sense of mastery (control) help older immigrants adjust to changes in family relationships. It is important for practitioners to remain mindful of how family relationships affect older immigrants’ health. Further, if older immigrants have no social ties outside their families, the companionship of family members may not always be sufficient to stave off loneliness (Treas & Mazumdar, 2002). Increasing the size of an immigrant’s overall social network can buffer the impact of relationship stress, especially for late-life immigrants. Ethnic community organizations can enhance informal support networks by highlighting and addressing the unique needs of older adults and providing targeted services.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported a grant from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health to the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan [T32-AG000221]. Data used for this research were provided by the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), managed by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan and supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health [U01AG009741].

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Open research statement

As part of IARR’s encouragement of open research practices, the author has provided the following information: This research was not pre-registered. The data used in the research are cannot be publicly shared but are available upon request. The data can be obtained at: the website of the Health and Retirement Study or by emailing: hrsquestsions@umich.edu. The materials used in the research cannot be publicly shared but are available upon request. The materials can be obtained by emailing: heejungj@umich.edu

In this article, we use the term “older immigrants” to refer to all immigrants age 65 and over regardless of when they arrived in the United States. We use the term “late-life immigrants” to refer to those who arrived in the United States at age 45 or older. While “late-life immigrants” usually refers to those who arrived at age 50 or older, we expand the group in this study to address concerns related to sample size. See the “Method” section for more detail.

References

- Ajrouch KJ (2008). Social isolation and loneliness among Arab American elders: Cultural, social, and personal factors. Research in Human Development, 5(1), 44–59. 10.1080/15427600701853798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch KJ, Blandon AY, & Antonucci TC (2005). Social networks among men and women: The effects of age and socioeconomic status. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(6), S311–S317. 10.1093/geronb/606.S31110.1093/geronb/60.6.s311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel JL, Angel RJ, & Markides KS (2000). Late-life immigration, changes in living arrangements, and headship status among older Mexican-origin individuals. Social Science Quarterly, 81(1), 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Angel JL, Buckley CJ, & Sakamoto A (2001). Duration or disadvantage? Exploring nativity, ethnicity, and health in midlife. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(5), S275–S284. 10.1093/geronb/56.5.S275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Birditt KS, Sherman CW, & Trinh S (2011). Stability and change in the intergenerational family: A convoy approach. Ageing and Society, 31(7), 1084–1106. 10.1017/S0144686X1000098X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Spitzer A, & Bell M (1996). Family stress and support among former soviet immigrants. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 18(6), 655–674. 10.1177/019394510.1177/019394599601800604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, & Gonzalez MC (1988). Loneliness, negative life events, and the provisions of social relationships. Communication Quarterly, 36(1), 1–15. 10.1080/01463378809369703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, & Thisted RA (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. 10.1037/a0017216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarota SA, & Zeigler K (2019). Projecting the impact of immigration on the US population. Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder. https://cis.org/Report/Projecting-Impact-Immigration-US-Population [Google Scholar]

- Carr S, & Tienda M (2013). Family sponsorship and late-age immigration in aging America: Revised and expanded estimates of chained migration. Population Research and Policy Review, 32(6), 825–849. 10.1007/s11113-013-9300-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, & Feeley TH (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(2), 141–161. 10.1177/026540751348872810.1177/0265407513488728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Liu G, & Mair CA (2011). Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. Social Forces, 90(2), 571–594. 10.1093/sf/sor012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J, Van der Pas S, & Keating N (2015). Loneliness of older immigrant groups in Canada: Effects of ethnic-cultural background. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 30(3), 251–268. 10.1007/s10823-015-9265-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami A, Torres S, Lipson JG, & Ekman SL (2000). An ethnographic study of a day care center for Iranian immigrant seniors. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(2), 169–188. 10.1177/019394590002200205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Sechrist J, & Birditt K (2013). Changing views on intergenerational ties. Gerontology, 59(1), 64–70. 10.1159/000342211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske A, Wetherell JL, & Gatz M (2009). Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 363–389. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller HR, Ajrouch KJ, & Antonucci TC (2020). Original voices the convoy model and later-life family relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 12(2), 126–146. 10.1111/jftr.12376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Dong X, & Tiwari A (2017). Family and marital conflict among Chinese older adults in the United States: The influence of personal coping resources. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 72(suppl 1), S50–S55. 10.1093/gerona/glw129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Li M, Xu H, Stensland M, Wu B, & Dong X (2021). Age at migration and cognitive health among Chinese older immigrants in the United States. Journal of Aging and Health, 33(9), 709–720. Online First. 10.1177/08982643211006612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Stensland M, Li M, Dong X, & Tiwari A (2019). Is migration at older age associated with poorer psychological well-being? Evidence from Chinese older immigrants in the United States. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 865–876. 10.1093/geront/gny066marsi [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossen A (2012). Social isolation and loneliness among elderly immigrants: The case of South Asian elderly living in Canada. Journal of International Social Issues, 1(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Gonzales FA, Serrano A, & Kaltman S (2014). Social isolation and perceived barriers to establishing social networks among Latina immigrants. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(1-2), 73–82. 10.1007/s10464-013-9619-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Pilkauskas NV, & Tang F (2020). Age at immigration and depression: The mediating role of contemporary relationships with adult children among older immigrants. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. Online First. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasso G (2003). Migration, human development, and the life course. In Handbook of the life course (pp. 331–364). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, & Antonucci TC (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In Baltes PB, & Brim OB (Eds) Life-span development and behavior, (Vol. 3, pp. 253–268). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M (2017). Family structure and the well-being of immigrant children in four European countries. International Migration Review, 51(4), 927–963. 10.1111/imre.12262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, & Dykstra PA (2006). Differentials in face-to-face contact between parents and their grown-up children. In Dykstra PA, Kalmijn M, Knijn TCM, Komter AE, Liefbroer AC, & Mulder CH (Eds), Family solidarity in the Netherlands (pp. 63–87). Dutch University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC, Kim S, & Hurh WM (1991). Filial piety and intergenerational relationship in Korean immigrant families. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 33(3), 233–245. 10.2190/Y91P-UNGR-X5E1-175K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder AG, Guzder J, Hassan G, Rousseau C, & Pottie K (2011). Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. Cmaj, 183(12), E959–E967. 10.1503/cmaj.090292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton L, Silverstein M, & Bengtson V (1994). Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56(1), 57–68. 10.2307/352701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leu J, Yen IH, Gansky SA, Walton E, Adler NE, & Takeuchi DT (2008). The association between subjective social status and mental health among Asian immigrants: Investigating the influence of age at immigration. Social Science & Medicine, 66(5), 1152–1164. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Krause NM, & Bennett JM (2001). Social exchange and well-being: Is giving better than receiving? Psychology and Aging, 16(3), 511–523. 10.1037/0882-7974.16.3.51110.1037//0882-7974.16.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Dong X, Nguyen D, & Lai DWL (2017). Family relationships and depressive symptoms among Chinese older immigrants in the United States. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 72(suppl 1), S113–S118. 10.1093/gerona/glw138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiter S (2003). The context of culture: Social work practice with Canadians of South Asian background. In Al-Krenawi A, & Graham JR (Eds), Multicultural Social Work in Canada (pp. 365–387). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Booth JM, Baldwin A, & Ayers S (2013). Acculturation and life satisfaction among immigrant Mexican adults. Advance in Social Work, 14(1), 49–64. 10.18060/3758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences (2020). Engineering, and medicine. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaru G, Schroeders U, Hartung J, Wilhelm O, & Wrzus C (2019). Ant colony optimization and local weighted structural equation modeling. A tutorial on novel item and person sampling procedures for personality research. European Journal of Personality, 33(3), 400–419 10.1002/per.2195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang EC, Jordan-Marsh M, Silverstein M, & Cody M (2003). Health-seeking behaviors of elderly Chinese Americans: Shifts in expectations. The Gerontologist, 43(6), 864–874. 10.1093/geront/43.6.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HJ, & Kim CG (2013). Ageing in an inconvenient paradise: The immigrant experiences of older Korean people in New Zealand. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 32(3), 158–162. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00642.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman D (2004). European and Canadian studies of loneliness among seniors. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23(2), 181–188. 10.1353/cja.2004.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, & Sorensen S (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta- analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245–266. 10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponizovsky AM, & Ritsner MS (2004). Patterns of loneliness in an immigrant population. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 45(5), 408–414. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rote S, & Markides K (2014). Aging, social relationships, and health among older immigrants. Generations, 38(1), 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Routasalo PE, Savikko N, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE, & Pitkälä KH (2006). Social contacts and their relationship to loneliness among aged people–a population-based study. Gerontology, 52(3), 181–187. 10.1159/000091828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P (2004). Multiple imputation of missing values. The Stata Journal, 4(3), 227–241. 10.1177/1536867x0400400301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saraga M, Gholam-Rezaee M, & Preisig M (2013). Symptoms, comorbidity, and clinical course of depression in immigrants: Putting psychopathology in context. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(2), 795–799. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, & Siahpush M (2001). All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91(3), 392–399. 10.2105/ajph.91.3.392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluzki CE (1992). Disruption and reconstruction of networks following migration/relocation. Family Systems Medicine, 10(4), 359–363. 10.1037/h0089043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz TT (2009). Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: Patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 191–212. 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treas J (2008). Four myths about older adults in America’s immigrant families. Generations, 32(4), 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Treas J, & Mazumdar S (2002). Older people in America’s immigrant families: Dilemmas of dependence, integration, and isolation. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(3), 243–258. 10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00048-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gaalen RI, Dykstra PA, & Komter AE (2010). Where is the exit? Intergenerational ambivalence and relationship quality in high contact ties. Journal of Aging Studies, 24(2), 105–114. 10.1016/j.jaging.2008.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Fox S, Wilson J, Stuart J, & Kus L (2010). Contextual influences on acculturation processes: The roles of family, community and society. Psychological Studies, 55(1), 26–34. 10.1007/s12646-010-0003-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth JM, & Chen PC (2003). Immigrant status, living arrangements, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(5), S305–S313. 10.1093/geronb/58.5.S305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, & Penning M (2015). Immigration and loneliness in later life. Ageing and Society, 35(1), 64–95. 10.1017/S0144686X13000470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakahi WR, & Duran RL (1985). Loneliness, communicative competence, and communication apprehension: Extension and replication. Communication Quarterly, 33(1), 50–60. 10.1080/01463378509369578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]