Abstract

Background

Numerous biomarkers are being tested to enhance the ability of clinicians to predict responses and prognosis after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) is a histone methyltransferase family that plays a major role in chromatin silencing. Preclinical evidence implicates PRC2 components such as enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) in immune resistance. This study aimed to assess the clinical relevance of PRC2 mutations in the clinical outcome of ICI-treated patients.

Materials and methods

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) data from tumor samples of patients treated with ICIs (anti-PD-1/PD-L1, anti-CTLA-4 or both) were interrogated for alterations in PRC2-related genes. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to assess the association between altered and unaltered PRC2-related genes with overall survival.

Results

Somatic NGS data from 1662 advanced-stage, ICI-treated patients with various primaries (lung, melanoma, bladder, kidney, head neck, esophagogastric, glioma, colorectal, breast, unknown primary) were examined. Seventy patients (4%) harbored truncating or missense mutations or fusions in EZH2 (2.4%), EZH1 (1.2%), SUZ12 (0.9%) or EED (0.7%) genes. Patients carrying alterations in PRC2 genes had significantly longer median overall survival (44 months) compared with those with unaltered tumors (18 months, log-rank P=0.0174). These findings were validated in two additional cohorts of patients (n=313) with various primaries (melanoma, lung, bladder, head neck, anal, sarcoma) who were treated with ICIs.

Conclusions

Inactivating mutations in the PRC2 chromatin silencing machinery, although rare, may predict favorable outcomes in ICI-treated patients with metastatic cancers. This warrants prospective confirmation, and suggests that epigenetic regulators could serve as surrogate markers to guide ICI treatment decisions.

Key words: PRC2, PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA-4, epigenetic regulation, overall survival, advanced cancer

Highlights

-

•

The PRC2 complex is a histone methyltransferase family involved in chromatin silencing.

-

•

This study assessed the clinical relevance of PRC2 mutations in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

-

•

Next-generation sequencing data from metastatic patients treated with ICIs showed alterations in EZH2, EZH1, SUZ12 and EED.

-

•

Patients with alterations in PRC2 genes had longer overall survival compared with those with unaltered tumors.

-

•

These findings were validated in two additional cohorts with various primaries treated with ICIs.

-

•

Epigenetic regulators could serve as surrogate markers to guide ICI treatment decisions.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have become part of the treatment armamentarium for patients with advanced cancer of different primaries.1 Tissue-based biomarkers, such as programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immunohistochemistry, are widely used to guide the selection of patients to receive anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies.2 However, PD-L1 has several limitations due to discordance in assay methodology and trial designs, as well as absence of prospective comparisons of how PD-L1-positive disease diagnosed using each assay relates to clinical outcomes.3 Besides PD-L1, numerous biomarkers are being tested to enhance the ability of clinicians to predict responses and prognosis of patients treated with ICIs. Other response biomarker candidates, including DNA mutations and neoantigen load, are only weak predictors of immune checkpoint blockade response.4 Thus, identification of novel, more robust biomarkers that could help predict which patients could benefit from ICIs remains an unmet need. Of particular interest is the development of signatures from gene expression profiling of immune cells within the tumor microenvironment.5 Additionally, gene alterations affecting chromatin remodeling and DNA methylation could play an important role in shaping response and resistance after treatment with ICIs.6

Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) is a histone methyltransferase family that plays a major role in chromatin silencing.7 The broader family of Polycomb group genes is well conserved in animals, and its gene products assemble into large multimeric protein complexes functioning as negative regulators of gene transcription during development.8 PRC2 is a methyltransferase with activity toward lysine 27 on histone H3. The SET-domain-containing component (EZH1 or EZH2) is closely associated with several other subunits. The core complex necessary for catalytic function consists of EZH1/2, the Zinc-finger protein SUZ12, and the WD40 protein EED.9

PRC2 can have both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive properties as a consequence of its molecular function in promoting a transcriptional repression state of numerous target genes.10 The cell-cycle-coupled expression of PRC2 components, and the presence of PRC2 overexpression in the stem-cell compartment suggest that increased PRC2 expression in cancer cells may stem from the increased proliferative capacity and/or dedifferentiated phenotype of cancer cells.9 Increased PRC2 activity may act as a driver in some cancers, evidenced by the occurrence of hyperactivating mutations as an early event through studies of clonality.11 Meta-analyses of numerous studies have revealed an association between PRC2 overexpression and poor prognosis across 18 different types of cancer.12 Recent in vitro and early clinical studies implicate key PRC2 components such as enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) in immune resistance13,14 through various mechanisms, including repression of T helper 1 (TH1)-type chemokines,15 downregulation of interferon-gamma signaling,14,16 downregulation of PD-L1 expression,17 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I and -II expression.18,19 However, there is a paucity of evidence with respect to the clinical significance of these observations in patients treated with ICIs. This study aimed to assess the prognostic relevance of PRC2 mutations in patients with advanced cancer of various primaries after treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 or/and anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) ICIs.

Materials and methods

This study used a publicly available database, cBioportal for Cancer Genomics (www.cbioportal.org),20 with targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) data from a cohort of 1662 patients who were treated with at least one dose of ICI, representing a variety of cancer types.21 The NGS assay used was MSK-IMPACT (Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets), and this identifies somatic exonic mutations in a pre-defined subset of 468 cancer-related genes using both tumor-derived and matched germline normal DNA.22 NGS data from corresponding tumor samples of these patients were queried for mutations and fusions in PRC2-related genes. cBioPortal supports the annotation of variants from several different databases. These databases provide information about the recurrence of, or prior knowledge about, specific amino acid changes. For each variant, the number of occurrences of mutations at the same amino acid position present in the COSMIC database are reported. Furthermore, variants are annotated as ‘hotspots’ if the amino acid positions are found to be recurrent linear hotspots, as defined by the Cancer Hotspots method (cancerhotspots.org), or three-dimensional hotspots, as defined by 3D Hotspots (3dhotspots.org). Prior knowledge about variants, including clinical actionability information, is provided from three different sources: OncoKB (www.oncokb.org), CIViC (civicdb.org) and My Cancer Genome (mycancergenome.org). Copy number data sets within the portal are generated by the GISTIC or RAE algorithms. Both algorithms attempt to identify significantly altered regions of amplification or deletion across sets of patients. Both algorithms also generate putative gene/patient copy number specific calls, which are then input into the portal.

The BIOKARTA_PRC2_PATHWAY gene set from the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis molecular signatures database (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp)23 was used as a reference to include the most important PRC2-related genes in the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) pathway genes

| BIOCARTA_PRC2_PATHWAY | Gene family |

|---|---|

| BMI1 | Transcription factor |

| CBX4 | Transcription factor |

| COMMD3-BMI1 | Read-through transcription |

| EEDa | Transcription factor |

| EZH1a | Transcription factor |

| EZH2a | Transcription factor |

| HDAC1 | Transcription factor |

| HDAC2 | Transcription factor |

| PHC1 | Transcription factor |

| RBBP4 | Histone binding |

| RBBP7 | Histone binding |

| RING1 | Transcription factor |

| SUZ12a | Oncogene, translocated cancer gene |

| YY1 | Transcription factor |

‘Core’ PRC2 genes.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to assess the association between altered and unaltered PRC2 pathway genes with overall survival (OS). OS was measured from the date of first ICI treatment to time of death or last follow-up.

Molecular data from two separate patient cohorts, consisting of patients with various primaries,24,25 were analysed in a combined metadataset as a means to validate findings from the discovery dataset21 with respect to the prognostic and predictive role of PRC2 pathway genes. All results were reported at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

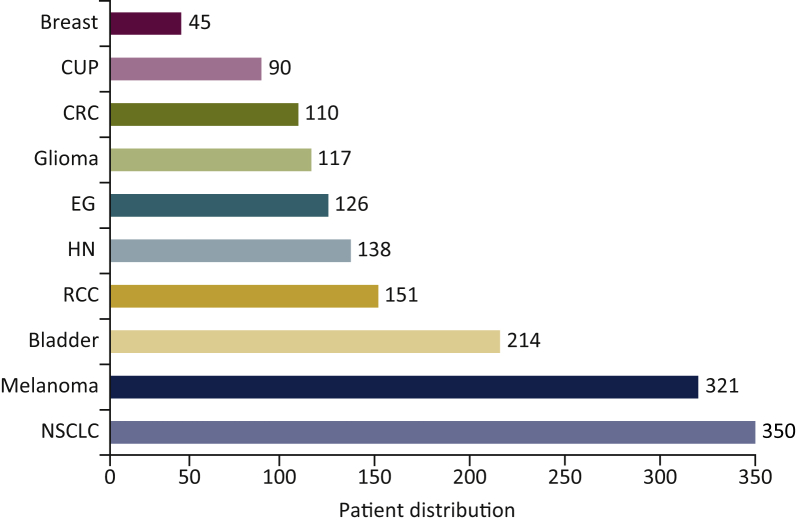

In total, 1662 patients with advanced-stage cancers were examined. The majority of patients had metastatic disease (n=1446, 94%), while the rest had either locally advanced, unresectable disease (n=989, 59%) or locally recurrent disease (n=10, 0.6%), as described previously.21 Primaries included non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, n=350), melanoma (n=321), bladder cancer (n=214), renal cell carcinoma (n=151), 138 head and neck cancer (n=138), esophagogastric cancer (n=126), glioma (n=117), colorectal cancer (n=110), cancer of unknown primary (n=90) and breast cancer (n=45) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient distribution by cancer type (discovery cohort).

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; CUP, cancer of unknown primary; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; EG, esophagogastric cancer; HN, head and neck cancer; CRC, colorectal cancer.

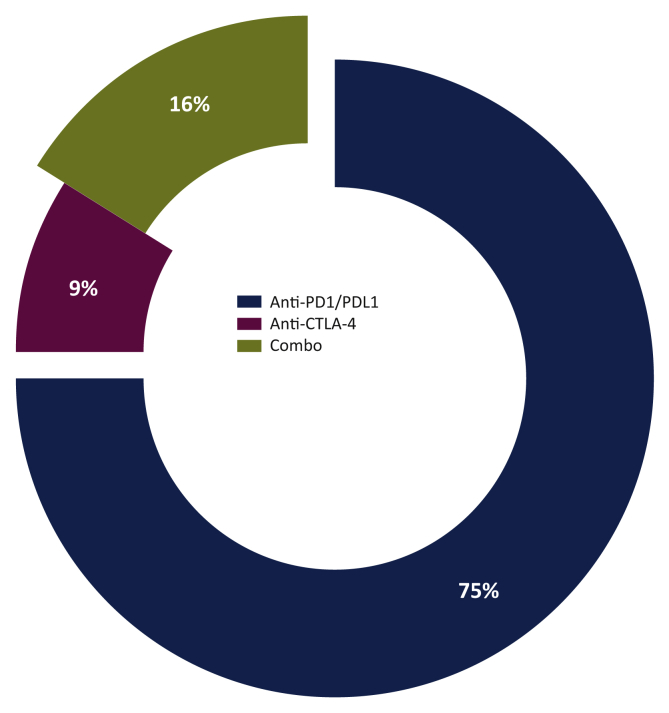

The majority of patients received a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor: nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, avelumab or durvalumab (n=1256). One hundred and forty-six patients were treated with anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab or tremelimumab), and the rest were treated with combinations (n=260) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient distribution by treatment (discovery cohort).

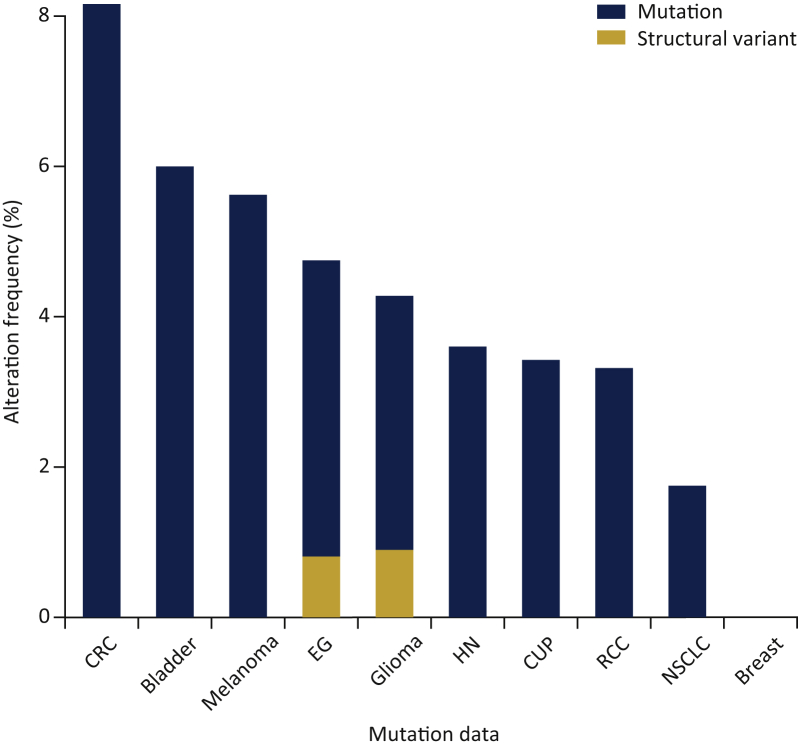

Upon query of the cohort's genomic data for molecular alterations within the BIOKARTA_PRC2_PATHWAY gene set, tumors from 70 patients (4%) were found to harbor truncating or missense mutations in EZH2 (2.4%), EZH1 (1.2%), SUZ12 (0.9%) or EED (0.7%) genes (Table 2 and Table S1, see online supplementary material). The presence of these alterations was most common in colorectal cancer (8.2%), followed by bladder cancer (6.2%), melanoma (5.6%), esophagogastric cancer (4.8%), glioma (4.3%), head and neck cancer (3.6%), cancer of unknown primary (3.4%), renal cell carcinoma (3.3%) and NSCLC (1.7%) (Figure 3). No significant co-occurrence or mutual exclusivity of mutations or fusions was detected among PRC2-related genes.

Table 2.

Mutations per Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) gene in tumor samples of patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (discovery cohort)

| PRC2 gene | Missense | Truncating | Inframe | Splice | Structural variant/fusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2 (2.4%) | 29 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| EZH1 (1.2%) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SUZ12 (0.9%) | 14 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EED (0.7%) | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Figure 3.

Frequency of alterations in Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes by cancer type (discovery cohort).

CRC, colorectal cancer; EG, esophagogastric cancer; HN, head and neck cancer; CUP, cancer of unknown primary; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

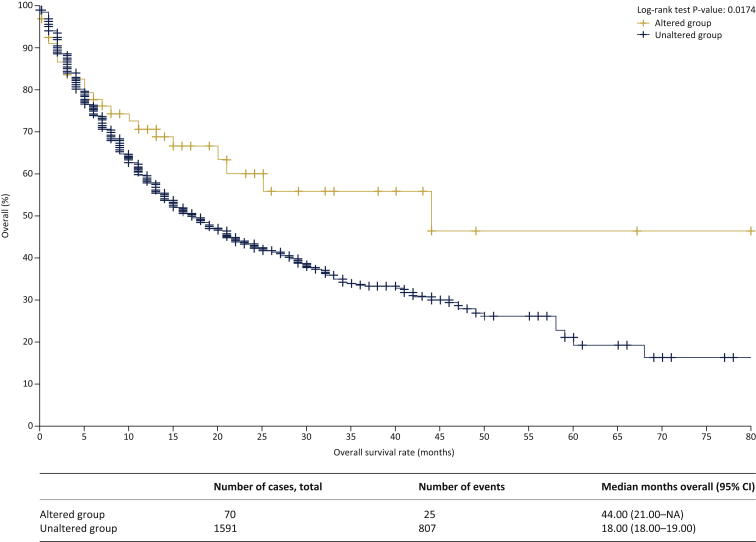

The median follow-up was 19 months (range 0-80 months), with 830 (50%) patients alive and censored at last follow-up, as described previously.21 Patients carrying somatic alterations in PRC2-related genes had a significantly longer median OS (44 months) compared with those without somatic alterations in PRC2-related genes (18 months, log-rank P=0.0174) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of patients with and without alterations in Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes (discovery cohort).

NA, not available; CI, confidence interval.

To validate these findings, a query for alterations in these PRC2-related genes was performed in a validation metadataset derived from tumors of patients with melanoma (n=215), NSCLC (n=57), bladder cancer (n=27), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (n=12), anal cancer (n=1) and sarcoma (n=1) treated with anti-PD-1 (n=74), anti-PD-L1 (n=20), anti-CTLA-4 (n=209), or a combination of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/L1 therapies (n=10).24,25 Queried genes were altered in 41 (13%) patients/samples (Figure S1, see online supplementary material). The presence of alterations in the same four PRC2-related genes (EZH2 8%, EZH1 2.2%, SUZ12 2.2%, EED 2.2%) was associated with longer median OS (48 months) compared with those without alterations (22 months, log-rank P=0.102) (Figure S2, see online supplementary material). There was also a trend towards longer progression-free survival of 22 versus 16 months, respectively (log-rank P=0.555) (Figure S3, see online supplementary material).

Discussion

PRC2 is a histone methyltransferase family that plays a major role in chromatin silencing.7 Increased PRC2 activity may act as a driver in some cancers, evidenced by the occurrence of hyperactivating mutations as an early event through studies of clonality.11 Meta-analyses of numerous studies have revealed an association between PRC2 overexpression and poor prognosis across 18 different types of cancer.12 The focus of this study was to examine the clinical value of molecular alterations in the PRC2 chromatin silencing machinery in patients with advanced cancer treated with ICIs. Mutations in key PRC2-related genes including EZH1, EZH2, EED and SUZ12 were associated with favorable outcomes in both the discovery and validation cohorts used. It is plausible that attenuation of histone methylation induced by these transcriptional repressors may have a positive effect on the outcomes of these patients treated with ICIs.

An association between epigenetic features and response to PD-1 inhibitors was reported previously in stage IV NSCLC patients, whereby the microarray DNA methylation signature EPIMMUNE was positively correlated with improved progression-free survival and OS.26

While prospective confirmation of the results of these studies is warranted, it is conceivable that epigenetic regulators could serve as surrogate markers to guide ICI treatment decisions. Although the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood, a previously described role of DNA methylation in silencing of PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2 and CTLA-4 gene expression could explain the inhibition or attenuation of immunotherapy efficacy in such patients.27,28

Taken together, the results of this study and the positive effect of demethylation on transcriptional activity for some immune-related genes, including PD-L1 and genes of the interferon signaling cascade, pose important therapeutic implications for use of epigenetic modulation as a tool to sensitize patients to anti-PD-L1 ICIs.29 For example, the demethylating drug azacytidine combined with an anti-CTLA-4 ICI led to greater tumor regression compared with each drug alone by upregulating MHC-I components.30 Increased lymphocyte infiltration and TH1-type chemokine and cytokine production were also observed after concurrent demethylation and anti-PD-L1 and CTLA-4 therapy in an ovarian cancer mouse model.31

This study was limited by heterogeneity of the discovery and validation patient cohorts with regard to different primaries, number of prior therapies, and timing of NGS testing relative to ICI initiation.21 Additionally, as this was a hypothesis-generating analysis of previously reported genomic data21,24,25 through the lens of epigenetic regulation, it underscores the effects of other genomic or/and epigenomic alterations on OS, focusing on mutations and fusions of PRC2-related genes. Additionally, the complex and very context-dependent effects of PRC2 mutations on diverse sets of cancers, as well as on the immune system- PRC2 loss can either be tumor suppressive or tumor promoting, depending on cancer (sub) type and other co-occurring driver mutations- is also underestimated. Taken together with the rare occurrence of PRC2 mutations in most cancers, the potential utility of PRC2 mutations as a potential biomarker for the effects of immune checkpoint inhibition warrants confirmation in large prospective analyses.

Future studies that integrate other genomic or/and histopathologic biomarkers may allow for the development of an optimized predictive test to inform clinical decisions on the use of ICIs.32 If confirmed and prospectively validated, knowledge of the mutation status of PRC2-related genes could help to better identify patients who could benefit from ICIs. Taking this a step further, modulating the expression of PRC2 genes (e.g. EZH2) using small molecule inhibitors, such as CPI-1205, could improve antitumor responses elicited by anti-PD-1 or/and anti-CTLA-4 therapy.33 Demethylating agents and histone deacetylases are currently being tested in combination with ICIs in numerous clinical trials and types of malignancies. Correlative studies on genomic and epigenomic surrogates of response and resistance, wherever available, will be of key importance to better target specific subpopulations.

Acknowledgments

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

The author has declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iotech.2021.100035.

Supplementary data

Mutation frequency of Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes in validation metadataset.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival plot of patients with and without alterations in Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes (validation metadataset).

NA, not available; CI, confidence interval.

Kaplan–Meier progression-free survival plot of patients with and without alterations in Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes (validation metadataset).

NA, not available; CI, confidence interval.

References

- 1.Gong J., Chehrazi-Raffle A., Reddi S., et al. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:8. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0316-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doroshow D.B., Bhalla S., Beasley M.B., et al. PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:345–362. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vlachostergios P.J., Faltas B.M. The molecular limitations of biomarker research in bladder cancer. World J Urol. 2019;37:837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao Q., Nobre A., Piñeiro P., et al. Genetic and Epigenetic Biomarkers of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Response. J Clin Med. 2020;9:286. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibney G.T., Weiner L.M., Atkins M.B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e542–e551. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gate R.E., Cheng C.S., Aiden A.P., et al. Genetic determinants of co-accessible chromatin regions in activated T cells across humans. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1140–1150. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0156-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margueron R., Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011;469:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piunti A., Shilatifard A. The roles of Polycomb repressive complexes in mammalian development and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:326–345. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laugesen A., Højfeldt J.W., Helin K. Role of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) in transcriptional regulation and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a026575. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comet I., Riising E.M., Leblanc B., Helin K. Maintaining cell identity: PRC2-mediated regulation of transcription and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:803–810. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bödör C., Grossmann V., Popov N., et al. EZH2 mutations are frequent and represent an early event in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122:3165–3168. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang T., Wang Y., Zhou F., Gao G., Ren S., Zhou C. Prognostic value of high EZH2 expression in patients with different types of cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:4584–4597. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang D., Quiros J., Mahuron K., et al. Targeting EZH2 reprograms intratumoral regulatory T cells to enhance cancer immunity. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3262–3274. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zingg D., Arenas-Ramirez N., Sahin D., et al. The histone methyltransferase Ezh2 controls mechanisms of adaptive resistance to tumor immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 2017;20:854–867. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng D., Kryczek I., Nagarsheth N., et al. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature. 2015;527:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature15520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiffen J., Gallagher S.J., Filipp F., et al. EZH2 cooperates with DNA methylation to downregulate key tumor suppressors and IFN gene signatures in melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:2442–2454.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao G., Jin L.L., Liu C.Q., et al. EZH2 negatively regulates PD-L1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:300. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0784-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ennishi D., Takata K., Béguelin W., et al. Molecular and genetic characterization of MHC deficiency identifies EZH2 as therapeutic target for enhancing immune recognition. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:546–563. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burr M.L., Sparbier C.E., Chan K.L., et al. An evolutionarily conserved function of Polycomb silences the MHC class I antigen presentation pathway and enables immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;36:385–401.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.www.cbioportal.org Available at.

- 21.Samstein R.M., Lee C.H., Shoushtari A.N., et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng D.T., Mitchell T.N., Zehir A., et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for solid tumor molecular oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp Available at.

- 24.Snyder A., Makarov V., Merghoub T., et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao D., Margolis C.A., Vokes N.I., et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade in microsatellite-stable solid tumors. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1271–1281. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duruisseaux M., Martínez-Cardús A., Calleja-Cervantes M.E., et al. Epigenetic prediction of response to anti-PD-1 treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:771–781. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bally A.P., Austin J.W., Boss J.M. Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of PD-1 Expression. J Immunol. 2016;196:2431–2437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H., Bueso-Ramos C., DiNardo C., et al. Expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, PD-1 and CTLA4 in myelodysplastic syndromes is enhanced by treatment with hypomethylating agents. Leukemia. 2014;28:1280–1288. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wrangle J., Wang W., Koch A., et al. Alterations of immune response of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Azacytidine. Oncotarget. 2013;4:2067–2079. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Covre A., Coral S., Nicolay H., et al. Antitumor activity of epigenetic immunomodulation combined with CTLA-4 blockade in syngeneic mouse models. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1019978. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1019978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L., Amoozgar Z., Huang J., et al. Decitabine enhances lymphocyte migration and function and synergizes with CTLA-4 blockade in a murine ovarian cancer model. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1030–1041. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones P.A., Ohtani H., Chakravarthy A., De Carvalho D.D. Epigenetic therapy in immune-oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:151–161. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goswami S., Apostolou I., Zhang J., et al. Modulation of EZH2 expression in T cells improves efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3813–3818. doi: 10.1172/JCI99760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mutation frequency of Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes in validation metadataset.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival plot of patients with and without alterations in Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes (validation metadataset).

NA, not available; CI, confidence interval.

Kaplan–Meier progression-free survival plot of patients with and without alterations in Polycomb repressive complex 2 genes (validation metadataset).

NA, not available; CI, confidence interval.