Abstract

We developed a chemically defined medium (CDM) containing lactose or glucose as the carbon source that supports growth and exopolysaccharide (EPS) production of two strains of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. The factors found to affect EPS production in this medium were oxygen, pH, temperature, and medium constituents, such as orotic acid and the carbon source. EPS production was greatest during the stationary phase. Composition analysis of EPS isolated at different growth phases and produced under different fermentation conditions (varying carbon source or pH) revealed that the component sugars were the same. The EPS from strain L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus CNRZ 1187 contained galactose and glucose, and that of strain L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus CNRZ 416 contained galactose, glucose, and rhamnose. However, the relative proportions of the individual monosaccharides differed, suggesting that repeating unit structures can vary according to specific medium alterations. Under pH-controlled fermentation conditions, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains produced as much EPS in the CDM as in milk. Furthermore, the relative proportions of individual monosaccharides of EPS produced in pH-controlled CDM or in milk were very similar. The CDM we developed may be a useful model and an alternative to milk in studies of EPS production.

Production of exopolysaccharides (EPS) by lactic acid bacteria in milk is an important factor in assuring the proper consistency and texture of fermented food (14). These heteropolysaccharides are composed of linear and branched repeating units varying in size from tetra- to heptasaccharides. The final EPS of high molecular mass (1 × 106 to 2 × 106 Da) is formed by polymerization of several hundred to a few thousand of these repeating units.

Using milk as a fermentation medium, EPS yields range from 50 to 425 mg/liter (2, 3, 4, 10, 16). Although milk medium is relevant to the food industry, EPS isolation from such a complex medium is tedious and time-consuming. Furthermore, EPS purification is hindered by glycohydrolases present in the crude preparations that are capable of degrading EPS. MRS, the usual medium for laboratory fermentation using Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, contains compounds (e.g., beef extract, peptone, yeast extract) that interfere with the analysis of EPS (12). Semidefined medium developed by Kimmel and Roberts (12) and chemically defined medium (CDM) developed by Grobben et al. (11) circumvent the problem of interference, but the ability of these media to support growth and EPS production of various strains of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus has not been evaluated, and no comparison between EPS produced in milk and in the defined medium is available.

In this work, we developed a CDM for two strains of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus for which EPS production and composition in milk have been previously studied. We examined the influence of medium constituents and fermentation parameters on growth, EPS yield, and sugar composition. Our results show that relative monosaccharide ratios in EPS are affected by pH and carbon sources. As expected, results were strongly strain dependent. In addition, we describe CDM conditions under which the relative monosaccharide composition of EPS is very similar to that of EPS extracted from milk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

EPS-producing L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains CNRZ 1187 and CNRZ 416 were obtained from the freeze-dried culture collection of the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (Jouy-en-Josas, France). CNRZ 1187 is a natural isolate of Greek homemade fermented milk; CNRZ 416 was initially isolated from a commercial starter. These strains were transferred to 10 ml of litmus milk and stored at −20°C.

CDM.

CDM contains (per liter of distilled water) 30 g of lactose or glucose; 4.0 g of sodium acetate; 1.0 g of tri-ammonium citrate; 2.0 g of KH2PO4; 2.0 g of K2HPO4; 0.5 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O; 0.05 g of MnSO4 · 1H2O; 0.02 g of FeSO4 · 7H2O; 0.2 g of CaCl2; 20 mg of adenine; 40 mg of xanthine; 0.4 g of cysteine; 0.3 g of aspartic acid; 0.3 g of glutamic acid; 0.2 g of each the following amino acids: alanine, arginine, glycine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, threonine, tryptophane, tyrosine, and valine; 0.5 g of orotic acid; 0.5 mg of p-aminobenzoic acid; 0.5 mg of folic acid, 2.0 mg of nicotinic acid; 2.0 mg of Ca-pantothenate; 1.0 mg of biotin; 2.0 mg of pyridoxal; 2.0 mg of riboflavin; and 1.0 mg of vitamin B12. The medium was autoclaved at 110°C for 10 min.

Fermentation conditions.

Batch fermentations without pH control were carried out in N2-flushed 100-ml screw-cap flasks with 80 ml of CDM for 96 h of incubation at 42°C. The fermentations controlled at pH 6.0 (the pH was maintained at 6.0 by the addition of 10 N NaOH) were carried out in a 2-liter fermentor (model SET002M; NBS SARL-IncelTech; Toulouse, France) containing 1,500 ml of CDM under slight agitation (150 t/min) for 40 h of incubation at 42°C. Cultures were inoculated with an 8-h preculture in CDM (1:20, vol/vol). For tests with 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 g of glucose or lactose per liter without pH control, samples were taken in the stationary phase after 48 h of incubation at 42°C.

Samples were examined (as relevant) for growth, pH determination, glucose utilization, and EPS isolation. After incubation the cultures were kept on ice, and cell numbers were determined microscopically by counting individual cells after methylene blue staining (15). The resulting values were expressed as direct microscopic counts of cells per milliliter. The pH was measured with a pH meter equipped with an Ingold electrode. Glucose consumption was analyzed with the glucose-oxidase, peroxidase 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) (ABTS) kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France).

For fermentations in milk medium, reconstituted nonfat dry milk (10%, wt/vol) was sterilized at 110°C for 10 min. Eighty-milliliter aliquots contained in 100-ml screw-cap flasks were inoculated with an 8-h preculture in milk (1:100, vol/vol) and incubated over different periods at 42°C.

Protein determination.

Contaminating protein was analyzed by the Pierce test with a bicinchonic acid kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) (data not shown). EPS extracts derived from CDM cultures in which the carbon source and time of harvesting were varied contained between 20 and 57% protein and between 13 and 64% EPS. (In contrast, the EPS yield represents only ∼1% of similar extracts when a milk medium is used [unpublished data].) Presumably, Lactobacillus strains secrete proteins that accumulate in the CDM. However, as protein contamination does not disturb phenol sugar determination and gas-liquid chromatography of alditol acetates, the presence of protein in the initial extract is readily overcome.

EPS isolation and total sugar determination.

EPS was isolated by ethanol precipitation as described (4), but the precipitation method was simplified for the culture in CDM. After removal of cells by centrifugation (16,000 × g for 10 min), the crude EPS was precipitated at 4°C by addition of 2 volumes of ethanol (100%). The resulting precipitate was collected after centrifugation (16,000 × g for 15 min) and redissolved in water. The crude EPS solution was dialyzed at 4°C. The total sugar concentration was determined by the phenol-sulfuric acid method using glucose as a standard (8). Results are expressed as milligrams of glucose per liter.

Monosaccharide composition of isolated EPS.

For quantitative sugar analysis, EPS was hydrolyzed with 4 N trifluoroacetic acid at 110°C for 16 h. When a precipitate (corresponding to protein and salt not completely eliminated by dialysis) appeared upon alkalinization, it was eliminated by centrifugation before derivation of the component sugars to alditol acetates (1). The alditol acetate contents were determined (using inositol as an internal standard) by gas-liquid chromatography on a fused-silica capillary column (30 m by 0.32 mm). The column temperature was 210°C, the injector temperature was 210°C, the detector temperature was 240°C, the split rate was 60 to 80 ml/min, and the carrier gas was hydrogen maintained at a pressure of 0.7 × 105 Pa. Results are expressed as a percentage of the total EPS.

RESULTS

Adaptation of CDM for EPS production by L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains.

L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains show significant variation in their ability to grow in different defined media. For this reason, Morishita et al. (13) previously developed four basal media, each adapted to a different Lactobacillus species (L. plantarum, L. casei, L. helveticus, and L. acidophilus). Starting with basal media adapted for L. helveticus, we modified and further adapted the medium for growth and EPS synthesis of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains CNRZ 1187 and CNRZ 416. Note that, unlike the CDM of Grobben et al. (11), our CDM does not contain oligo-elements, thiamine, lipoic acid, guanine, uracil, or Tween 80; however, it does contain orotic acid, which is naturally present in milk (80 to 100 mg/liter).

The effects of different additives were tested, and results are summarized as follows. Flushing the CDM with nitrogen had a stimulating effect on both EPS production (resulting in a twofold increase) and growth. The addition of calcium chloride increased growth, and addition of orotic acid increased EPS yield almost threefold. Thiamine (2 mg/liter) added to CDM had a negative effect on both growth and EPS yield. Uracil and guanine did not effect growth or EPS production, while the addition of adenine and xanthine stimulated both growth and EPS synthesis. The optimal growth temperature of 42°C was also optimal for EPS yield (results not shown). The CDM was modified to optimize EPS production and is used as described in Materials and Methods in experiments presented below.

Growth characteristics, glucose consumption, and EPS production in CDM without pH control.

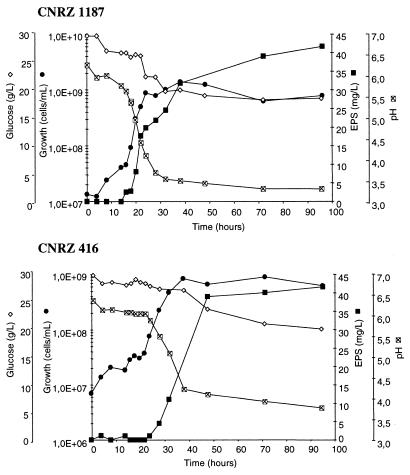

Under the conditions tested (see Materials and Methods), growth of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus CNRZ 1187 attained a maximum population of 109 cells/ml after 24 h, with a 16-h lag phase. L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus CNRZ 416 attained 9.5 × 108 cells/ml after 38 h, with a 20-h lag phase. Cultures of strain CNRZ 1187 were nearly fully acidified at 48 h (pH 3.6) and reached a final pH of 3.5 at 96 h. The pH of the medium with strain CNRZ 416 was higher than that of CNRZ 1187 after 48 h (pH 4.0), and a final pH of 3.7 was reached after 96 h (Fig. 1). Under these fermentation conditions, glucose utilization was slightly higher (11.5 g/liter) by strain CNRZ 1187 than by strain CNRZ 416 (10.0 g/liter) (Fig. 1). During exponential growth, glucose consumption was only 3.5 g/liter for strain CNRZ 1187 and 2.0 g/liter for CNRZ 416 (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Growth, pH, EPS production, and glucose utilization by L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. Strains CNRZ 1187 and CNRZ 416 were grown in non-pH-regulated CDM (30 g of glucose per liter) at 42°C. Each value represents the average of three measurements. The maximal deviation between the three measurements was 5% for growth and for glucose utilization and 10% for EPS production. Symbols: ●, growth; ×, pH; ■, EPS production; ◊, glucose utilization.

TABLE 1.

Glucose consumption and EPS production in L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains under various conditions

| Medium | Strain | Exponential phase

|

Stationary phase

|

Total

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose consumption (g/liter) | EPS production (mg/liter) | Glucose consumption (g/liter) | EPS production (mg/liter) | Glucose consumption (g/liter) | EPS production (mg/liter) | ||

| Milk | CNRZ 1187 | NDa | 40.0 | ND | 70.0 | ND | 110.0 |

| CNRZ 416 | ND | 40.0 | ND | 130.0 | ND | 170.0 | |

| CDM (30 g of glucose per liter) without pH control | CNRZ 1187 | 3.5 | 18.0 | 8.0 | 24.0 | 11.5 | 42.0 |

| CNRZ 416 | 2.0 | 11.0 | 8.0 | 31.0 | 10.0 | 42.0 | |

| CDM (30 g of glucose per liter) with pH control | CNRZ 1187 | 1.0 | 14.0 | 25.0 | 93.5 | 26.0 | 107.5 |

| CNRZ 416 | 3.5 | 50.0 | 19.5 | 124.0 | 23.0 | 174.0 | |

ND, not determined.

The timing of EPS synthesis was examined for the two strains, according to growth phase and medium. EPS production was almost 40 mg/liter after 72 h of fermentation for strain CNRZ 1187, while the same EPS yield was reached after 48 h of fermentation for strain CNRZ 416 (Fig. 1). In CDM, half of the total EPS was produced during the exponential phase for strain CNRZ 1187, compared to only one-third in milk (2). Strain CNRZ 416 produced one-third of the total EPS during the exponential phase, compared to only one-quarter in milk (Table 1). Despite these differences, it appears that for both strains, a majority of EPS is produced during the stationary phase.

Effect of glucose concentration and pH control on EPS synthesis.

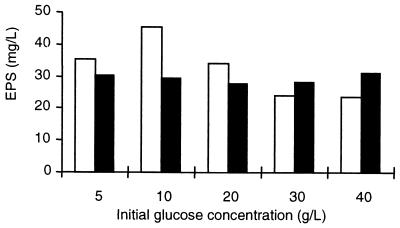

For strain CNRZ 416 without pH-controlled conditions, 10 g of glucose per liter seemed to be the optimal carbon source concentration for the highest EPS yield. The EPS yield of strain CNRZ 1187 appeared not to be affected by the sugar concentration of the medium (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the EPS yield of the two strains was higher with glucose than with lactose in the medium (results not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of initial glucose concentration on EPS produced by L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains grown in non-pH-regulated CDM. Each value represents the average of three measurements. The maximal deviation between the three measurements was 10%. Solid bars, strain CNRZ 1187; open bars, strain CNRZ 416.

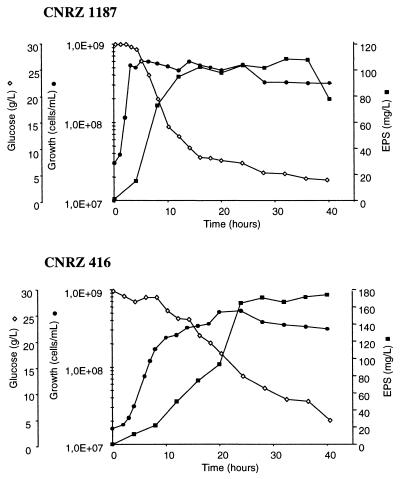

Growth under pH-controlled conditions resulted in a higher yield of EPS than that under non-pH-regulated conditions. Under pH-controlled conditions, the EPS yield of strain CNRZ 1187 was about 110 mg/liter, which is almost three times more than the amount obtained without pH control. For strain CNRZ 416, the EPS yield was 175 mg/liter, which is about four times more than the amount obtained without pH control (Fig. 3). For both strains, the EPS yields in CDM under pH-controlled conditions (pH 6) were about the same as those in milk. Strikingly, most EPS was produced at the end of growth, and 95% (CNRZ 1187) and 85% (CNRZ 416) of the glucose was consumed in the stationary phase (Table 1). This correlation suggests that the glucose consumed at this late phase is used for the production of EPS. Taken together, the above results indicate that a majority of EPS is produced during stationary phase, regardless of the medium.

FIG. 3.

Growth, EPS production, and glucose utilization by L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. Strains CNRZ 1187 and CNRZ 416 were grown in CDM (30 g of glucose per liter) under pH-controlled (pH 6.0) fermentation conditions at 42°C. Each value represents the average of three measurements. The maximal deviation between the three measurements was 5% for growth and for glucose utilization and 10% for EPS production. Symbols: ●, growth; ■, EPS production; ◊, glucose utilization.

Monosaccharide analysis of EPS.

The EPS produced by L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains CNRZ 1187 and CNRZ 416 are heteropolysaccharides composed mainly of galactose and glucose. Rhamnose was only found in the EPS from strain CNRZ 416. Mannose and arabinose were sometimes present, but in much smaller proportions. The presence of these sugars was independent of the medium and carbon source used for growth. The proportions of the different monosaccharides expressed as a percentage of the total were, however, quite different (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Relative monosaccharide composition of EPS produced by L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains under various conditions

| Strain | Medium | Carbon source | Phase | % Composition of EPSa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galactose | Glucose | Rhamnose | Mannose | Arabinose | ||||

| CNRZ 1187 | Milk | Lactose | Exponential | 61.7 | 33.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Stationary | 57.4 | 38.6 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | |||

| CDM without pH control | Lactose | Exponential | 39.7 | 57.9 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.6 | |

| Stationary | 51.6 | 47.3 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.4 | |||

| Glucose | Exponential | 39.7 | 57.9 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.6 | ||

| Stationary | 51.6 | 47.3 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.4 | |||

| CDM with pH control | Glucose | Exponential | 62.9 | 37.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Stationary | 63.0 | 37.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| CNRZ 416 | Milk | Lactose | Exponential | 75.2 | 13.8 | 9.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Stationary | 73.8 | 14.3 | 10.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | |||

| CDM without pH control | Lactose | Exponential | 83.6 | 8.3 | 6.4 | 1.1 | 0.6 | |

| Stationary | 85.3 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Glucose | Exponential | 70.6 | 13.1 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 0.0 | ||

| Stationary | 49.1 | 45.0 | 4.4 | 1.0 | 0.5 | |||

| CDM with pH control | Glucose | Exponential | 72.6 | 13.4 | 8.9 | 5.1 | 0.0 | |

| Stationary | 78.0 | 12.4 | 8.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | |||

Each value represents the average of three measurements. The maximal deviation between the three measurements was 5%.

For example, for strain CNRZ 1187, the proportions of monosaccharides in EPS produced either in milk or in CDM without pH control varied as a function of the growth phase but not of the carbon source. In CDM with the pH controlled at 6.0, the monosaccharide proportions remained constant for EPS produced during the exponential and stationary phases and were very similar to those of EPS produced in milk (Table 2). For strain CNRZ 416, the monosaccharide proportions of EPS produced in CDM or in milk were influenced by the growth phase but also by the carbon source in CDM without pH control when glucose or lactose was used as the carbon source. The monosaccharide proportions of EPS in CDM with the pH controlled at 6.0 gave results similar to those obtained in milk (Table 2). The above results show that conditions can be determined for CDM in which the L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus EPS monosaccharide composition is similar to that in milk medium.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we designed a CDM that allows growth of several L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains and allows high levels of EPS production when the pH is controlled. Previous studies showed that L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strain CNRZ 1187 (2) and CNRZ 416 (4) produce EPS during milk fermentation. The same strains also produce EPS in CDM with glucose or lactose as the carbon source, but in lower amounts if the pH is not controlled. A lower EPS yield in CDM compared to that milk was observed for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strain NCFB 2772 by Grobben et al. (11). We proposed that the higher EPS yields in milk during fermentation are due to small amounts of peptides liberated from milk proteins by the action of bacterial proteases (7). Our results show that when the pH was maintained at 6.0, EPS yields were the same as those obtained in milk for both strains tested. This CDM may prove useful for biochemical analysis or for screening L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains for the capacity to produce EPS. We noted that even after dialysis, the crude EPS preparations isolated from CDM contain protein produced by the bacteria, but in lesser amounts than that isolated from milk. In CDM, this contamination did not interfere with EPS measurements (see Materials and Methods), so the determination of monosaccharide composition was considerably simplified.

Our results are consistent with previous reports (10, 11) showing that L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus needs maximum bacterial growth for optimal EPS yields. EPS production by a strain of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was previously reported as being growth related, but no EPS synthesis was observed after cell growth had ceased (11). In sharp contrast to those previous results, most of the EPS synthesis and glucose utilization of the two strains tested here occurred in the stationary phase regardless of culture medium. For mesophilic lactic acid bacteria, growth at temperatures below 30°C is known to enhance EPS production (5, 6, 17). This is consistent with a proposed mechanism in which slow-growing cells exhibit much slower cell wall synthesis and accordingly have a decreased need for isoprenoid phosphate. As a consequence, more isoprenoid phosphate could be available for EPS synthesis (18). Thus, growth and EPS production may be in competition for lipid carriers. A possible interpretation of our results in thermophilic lactic acid bacteria is that isoprenoid phosphate carriers are primarily needed for cell wall synthesis growth. Upon cessation of growth, there is a greater availability of this intermediate for EPS synthesis. This may explain our finding that EPS production is increased in stationary phase cells.

It has been shown with L. casei (6) and L. rhamnosus (9), both mesophilic acid bacteria, that the presence of excess sugar in the medium (at concentrations between 10 and 20 g/liter) had a stimulating effect on EPS production, although growth was apparently reduced. The L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains in this study did not show this effect. For strain CNRZ 416, the optimal glucose or lactose concentration for both growth and EPS production is 10 g/liter, while strain CNRZ 1187 showed no influence of sugar concentration on EPS yield. Furthermore, the two strains did not show the same behavior with two different carbon sources; for strain CNRZ 416, the proportion of the sugar constituents varied as a function of the carbon source, while for the strain CNRZ 1187, it did not. These differences may highlight variations in EPS regulation and synthesis in different strains.

It is important to know for future studies whether the EPS produced from a particular strain of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in CDM is the same as that produced in milk. For this, different characteristics must be considered, including identification of the component monosaccharides, determination of their relative proportions, and determination of the physicochemical properties of the final EPS. From the present study, it can be concluded that independently of medium, carbon source, and fermentation parameters, the same monosaccharides are present in the different EPS extracted for one strain, i.e., galactose and glucose for strain CNRZ 1187 and galactose, glucose, and rhamnose for strain CNRZ 416. However, the relative proportions of monosaccharides do vary, indicating that the primary structures of EPS repetitive units are different according to the strain. The advantage of pH-controlled conditions is the considerable increase in EPS yield, as well as the monosaccharide proportions that are similar to what is obtained in milk medium. Physicochemical properties of the different EPS are under investigation to determine whether the different EPS produced in CDM can be compared in terms of structure and thickening properties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Alexandra Gruss from the Unité de Recherches Laitières et Génétique Appliquée, INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France, for her help in the reading of the manuscript. We also thank the Unité de Recherches sur la viande, INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France, for lending of the 2-liter fermentor (SET002M; NBS SARL-IncelTech) and Catherine Béal from the Laboratoire de Génie et Microbiologie des Procédés Alimentaires, INRA, Paris-Grignon, France, for her help in pH-controlled experiments.

This research was supported by a scholarship to Sandrine Petry from the Department of Chemistry of the University College Dublin, by Zeneca, and by EU contract FAIR-CT97-3098.

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to Jutta Cerning, who passed away on 3 October 1999.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blakeney A B, Harris P J, Henry R J, Stone B A. A simple and rapid preparation of alditol acetates for monosaccharide analysis. Carbohydr Res. 1983;113:291–299. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouzar F, Cerning J, Desmazeaud M. Exopolysaccharide production in milk by Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus CNRZ 1187 and by two colonial variants. J Dairy Sci. 1996;79:205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouzar F, Cerning J, Desmazeaud M. Exopolysaccharide production and texture-promoting abilities of mixed-strain starter cultures in yogurt production. J Dairy Sci. 1997;80:2310–2317. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerning J, Bouillanne C, Desmazeaud M J, Landon M. Isolation and characterization of exocellular polysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus bulgaricus. Biotechnol Lett. 1986;8:625–628. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerning J, Bouillanne C, Landon M, Desmazeaud M. Isolation and characterization of exopolysaccharides from slime-forming mesophilic lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75:692–699. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerning J, Renard C M G C, Thibault J F, Bouillanne C, Landon M, Desmazeaud M, Topisirovic L. Carbon source requirements for exopolysaccharide production by Lactobacillus casei CG11 and partial structure analysis of the polymer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3914–3919. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.3914-3919.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerning J, Marshall V M E. Exopolysaccharides produced by the dairy lactic acid bacteria. Recent Res Dev Microbiol. 1999;3:195–209. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaplin M F. Monosaccharides. A practical approach. In: Chaplin M F, Kennedy J F, editors. Carbohydrate analysis. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1986. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamar L, Blondeau K, Simonet J-M. Physiological approach to extracellular polysaccharide production by Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain C83. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;83:281–287. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Garibay M, Marshall V M E. Polymer production by Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70:325–328. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grobben G J, Sikkema J, Smith M R, de Bont J A M. Production of extracellular polysaccharides by Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772 grown in a chemically defined medium. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimmel S A, Roberts R F. Development of a growth medium suitable for exopolysaccharide production by Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus RR. Int J Food Microbiol. 1998;40:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morishita T, Deuchi Y, Yajima M, Sakurai T, Yura T. Multiple nutritional requirements of lactobacilli: genetic lesions affecting amino acid biosynthetic pathways. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:64–71. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.1.64-71.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricciardi A, Clement F. Exopolysaccharides from lactic acid bacteria: structure, production and technological application. Ital J Food Sci. 2000;12:23–45. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson D I, Eckberg L, Sherman G. Direct microscopic method for bacteria. In: Math E H, editor. Standard methods for the examination of dairy products. 14th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1978. pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toba T, Uemura H, Itoh T. A new method for the quantitative determination of microbial extracellular polysaccharide production using a disposable ultrafilter membrane unit. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1992;14:30–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.van den Berg D J C, Robijn G W, Janssen A C, Giuseppin M L F, Vreeker R, Kamerling J P, Vliegenthart J F G, Ledeboer A M, Verrips C T. Production of a novel extracellular polysaccharide by Lactobacillus sake 0-1 and characterization of the polysaccharide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2840–2844. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.2840-2844.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitfield C. Bacterial extracellular polysaccharides. Can J Microbiol. 1988;34:415–420. doi: 10.1139/m88-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]