Abstract

We developed a method to purify appressoria of the bean anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum lindemuthianum for biochemical analysis of the cell surface and to compare appressoria with other fungal structures. We used immunomagnetic separation after incubation of infected bean leaf homogenates with a monoclonal antibody that binds strongly to the appressoria. Preparations with a purity of >90% could be obtained. Examination of the purified appressoria by transmission electron microscopy showed that most had lost their cytoplasm. However, the plasma membrane was retained, suggesting that there is some form of attachment of this membrane to the cell wall. The purified appressoria can be used for studies of their cell surface, and we have shown that there are clear differences in the glycoprotein constituents of cell walls of appressoria compared with mycelium.

For many fungal plant pathogens, the appressorium is developmentally the first and most important infection structure formed in preparation for invasion of the host. Appressoria increase the area of contact and attachment between the fungus and host surface, provide the mechanical force and enzymes required for penetration, and can promote survival in adverse conditions (10). Species of Colletotrichum, the anthracnose fungi, produce melanized appressoria, and several mRNAs and proteins specific to these structures have been identified. For example, the cap20 gene in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides is induced by the surface wax of its host, avocado, and is expressed during appressorium formation (8). In Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, have been analyzed the cell surface of appressoria and other infection structures using lectins and monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (12, 13). A plasma membrane-associated glycoprotein specific to appressoria has also been identified using an MAb (16).

Our objective in this study was to purify C. lindemuthianum appressoria for further biochemical analysis of the cell surface and to compare appressoria with other fungal structures. To date, there have been no reports of the enrichment of appressoria from infected plant tissue, although appressoria produced on artificial substrata by species of Colletotrichum and Uromyces have been isolated by mechanical scraping (8, 9, 19). However, appressoria harvested in this way are contaminated with other fungal cell types, e.g., conidia and germ tubes, and there is evidence that appressoria formed in vitro do not have the same composition as appressoria formed on host surfaces (7).

A variety of methods have been used to isolate the inter- and intracellular infection structures formed by fungal pathogens inside infected plant tissues. These include enzymatic maceration (2) and mechanical disruption followed by either density gradient centrifugation (1, 3, 20) or lectin affinity chromatography (4). Immunomagnetic separation (IMS) has been widely used in animal cell biology and microbiology for the purification of cells, bacteria, and viruses from mixed cell populations (18). Magnetic Dynabeads (Dynal) coated with specific polyclonal antibodies or MAbs, lectins, or other ligands attach to target cells in a heterogenous suspension, and a magnet is used to separate the target cells from the sample. Isolation of the intracellular hyphae of C. lindemuthianum from infected bean tissues was the first reported use of IMS to purify fungal cells (15). IMS using the MAb UB25 yielded a sample which contained 30 to 40% intracellular hyphae, of which 60% were viable. More recently, preparations containing up to 95% intracellular hyphae with yields of 1 × 105 to 3 × 105 cells g (fresh weight) of leaf tissue−1 have been obtained (N. A. Pain, unpublished results). This increase was achieved by washing the hyphae attached to the magnetic beads with buffer and repeating the magnetic separation step (12).

In this paper, we describe the purification of appressoria of C. lindemuthianum from mixtures of infection structures by using IMS with MAb UB31. This antibody was described in a preliminary report, which showed that it bound strongly to appressoria (13). The purified appressoria are not viable and lack cytoplasm but can be used for studies of the cell surface, and we have shown that there are clear differences in the glycoprotein constituents of cell walls of appressoria compared with mycelium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal and plant material.

C. lindemuthianum (Sacc. and Magn.) Briosi and Cav., race γ (ATCC 56987; Long Ashton Research Station [LARS] culture number 129) and race κ (LARS 137), was maintained and conidial suspensions were prepared as described previously (15). Primary leaves were excised from seedlings of Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv. La Victoire, brush inoculated with conidial suspension, and incubated for 72 h at 17°C (15). After homogenization of the infected leaves using a blender, fungal infection structures were isolated from the homogenates using an isopycnic centrifugation (IPC) procedure (15). This IPC preparation contained, on average, 107 appressoria in total, with a purity of approximately 40%. Other components of the preparation were conidia, germ tubes, intracellular hyphae, plant cell wall fragments, starch grains, and chloroplasts.

Preparation of MAb UB31.

MAb UB31 was obtained after immunization of BALB/c mice with C. lindemuthianum infection structures (7). The antibody was selected for further study after screening tissue culture supernatants on IPC preparations of C. lindemuthianum infection structures by indirect immunofluorescence. UB31 labeled appressoria strongly and is an immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) with kappa light chains (13).

Purification of appressoria by IMS.

Appressoria were enriched from IPC preparations by IMS using MAb UB31. All steps of the procedure were performed at 4°C. The IPC preparation was centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 10 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of undiluted UB31 tissue culture supernatants. After incubation on a rotator (60 rpm) for 18 h, the cells were collected and washed four times by centrifugation as above, each time resuspending the pellet in 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove unbound antibody. The final pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of PBS containing M-450 Dynabeads (4.5-μm diameter) coated with rat anti-mouse IgG1 antibody (Dynal Ltd., Wirral, United Kingdom [U.K.]), diluted to give a bead/appressorium ratio of 4:1, and incubated for 1 h on a rotator. A further 5 ml of PBS was then added to dilute the cells and to minimize physical entrapment of contaminating particles in the bead-appressorium complexes before the tube was placed in a Dynal magnetic particle concentrator (MPC) for 5 min. The supernatant was removed with a Pasteur pipette, and the Dynabead fraction was removed from the MPC and then resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. To detach the beads from the appressorial cell surface, the Dynabead fraction was subjected to vigorous pipetting for 2 min and replaced in the MPC for a further 5 min prior to removal of the appressorium-rich supernatant. The numbers of appressoria and other cell types were monitored with a Fuchs-Rosentahl hemocytometer.

Microscopy.

Samples of C. lindemuthianum appressoria purified by IMS were examined by differential interference contrast microscopy. To assess the viability of the appressoria following IPC and IMS, cells were resuspended in an aqueous solution of 5 μM fluorescein diacetate (FDA; Sigma Chemical Co. Ltd., Poole, U.K.) and examined after 5 min by epifluorescence microscopy (15). Appressoria enriched by IMS and detached from the Dynabeads were prepared for transmission electron microscopy by propane jet freezing and freeze-substitution as described by Pain et al. (15), except that samples were embedded in Quetol epoxy resin (TAAB Laboratories Equipment Ltd., Reading, U.K.).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Cell wall-enriched fractions were prepared from purified appressoria and mycelium using the methods described previously for spores of C. lindemuthianum (6). Cell wall proteins were solubilized in reducing sample buffer and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by Western blotting of the proteins to nitrocellulose (6). The blots were incubated with MAb UB22, which recognizes cell surface glycoproteins of C. lindemuthianum, or MAb UBIM22, used as a negative control (14). Blots were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse Igs followed by the appropriate substrate to visualize the labeled proteins (6).

RESULTS

Fungal infection structures, including appressoria, were isolated from 72-h-infected bean leaf material by IPC. An indirect method of positive selection was used for the IMS, in which the appressoria were first coated with primary antibody, MAb UB31, before being incubated with Dynabeads coated with a secondary antibody specific for the primary antibody isotype. We used this approach because antibodies in solution find their target epitopes more readily than if the antibody is bound directly to the surface of a bead (21). IMS with MAb UB31 enriched appressoria from the original IPC preparation, and final yields were 3 × 105 appressoria g of leaf tissue−1, with a purity of 91% ± 1% (mean of four replicate experiments). The degree of contamination with other cell types, particularly chloroplasts, was markedly reduced compared to the original IPC preparation (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Numbers of C. lindemuthianum appressoria, conidia, intracellular hyphae, and chloroplasts obtained from homogenates of infected bean leaves by IPC or IPC followed by IMS using MAb UB31a

| Cell or organelle | IPC prepn

|

IMS prepn

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean purity (%) | Mean no. (105) | Mean yield (104 g−1) | Mean purity (%) | Mean no. (105) | Mean yield (104 g−1) | |

| Appressoria | 37 ± 6 | 160 ± 18 | 104 ± 13 | 91 ± 1 | 47 ± 4 | 30 ± 2 |

| Conidia | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 22 ± 4 | 14 ± 2 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| Intracellular hyphae | 6.6 ± 1.3 | 29 ± 5 | 19 ± 3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.84 ± 0.15 | 0.54 ± 0.09 |

| Chloroplasts | 51 ± 7 | 270 ± 110 | 170 ± 60 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

Results are the means ± standard errors from five replicate experiments. The range in appressorial cell numbers was 1.03 × 107 to 2.06 × 107 for the IPC preparation and 3.15 × 106 to 5.4 × 106 for the IMS preparation.

Several preliminary experiments were conducted to optimize the IMS protocol. The time for which inoculated bean leaves were incubated prior to isolation of infection structures affected the final yield of appressoria. Both the yield and purity of appressoria following IMS were lower with 40-h-infected leaves (yield, 3.9 × 104 g−1; purity, 76% ± 0.7%) compared to 72-h-infected leaves (yield, 3 × 105 g−1; purity, 91% ± 0.9%). An additional cycle of IMS improved the total number of appressoria in the final IMS preparation, but the relative purity of the appressoria did not increase. For example, in one experiment, a single round of IMS yielded 8.6 × 105 appressoria g−1 with a purity of 86%, whereas two rounds of IMS gave 3.3 × 106 appressoria g−1 with a purity of 77%. With appropriate antibodies, negative selection can be used to deplete unwanted cell types from the preparation (5). However, we chose not to use this approach, since in an earlier study negative selection was less efficient for purification of intracellular hyphae than positive selection using MAb UB25 (15).

Dynabeads were attached to the appressorial cell surface, including single appressoria and clusters of cells that had become aggregated during the isolation procedure (Fig. 1). Once attached to the Dynabeads, most appressoria could be removed by either vigorous pipetting or ultrasonication (120-μm amplitude, 23 kHz, and 50 W of power for 20 s). Ultrasonication released nearly all the appressoria from the beads, but many of the cells were disrupted, and the Dynabead fraction contained appressorial fragments associated with the bead surface and in the surrounding medium. In contrast, vigorous pipetting released approximately 85% of the appressoria from the beads, but these cells generally remained intact.

FIG. 1.

Appressoria (asterisks) of C. lindemuthianum purified by IMS and viewed with differential interference contrast microscopy. The Dynabeads (arrowheads) are attached to the surfaces of single appressoria (A) and groups of appressoria that have become aggregated during the isolation procedure (B). Bars, 10 μm.

When appressoria purified by IMS were stained with FDA, the cells did not fluoresce green (results not shown), indicating an absence of cytoplasmic esterase activity (17). This result suggested that the purified appressoria were not viable. However, appressoria in the IPC preparation also failed to stain with FDA, so the loss of cell viability was not caused by the IMS purification. It was possible that the appressorial cytoplasm had escaped through the basal penetration pore and ruptured penetration peg during the initial homogenization of infected tissue. Therefore, appressoria were prepared from bean leaves at 15 h, before the formation of penetration pegs and intracellular hyphae (11). However, the purified appressoria did not stain with either FDA or DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole), which stains nuclei (15), indicating lack of viability and loss of cytoplasm.

The ultrastructure of appressoria enriched by IMS was examined after freeze-substitution. The appressorial cell wall had a moderately electron-opaque inner layer and a highly electron-opaque outer layer surrounded by a loosely organized layer of extracellular matrix (Fig. 2A and B). Cell cytoplasm was well preserved in a few appressoria, but in most cases, appressoria did not contain any cytoplasm. Despite the loss of cytoplasm, appressoria retained an appressorial cone surrounding the penetration pore and a plasma membrane closely appressed to the cell wall. The appressorial plasma membrane was slightly undulating in profile and discontinuous, pulling away from some areas of the cell wall (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs showing appressoria of C. lindemuthianum purified by IMS and prepared by propane jet freezing and freeze-substitution. (A) The appressorium contains no cytoplasm but retains an intact appressorial cone (ac) around the basal penetration pore (asterisk) and remnants of the extracellular matrix (arrowheads). Bar, 1 μm. (B and C) Portions of empty appressoria. Despite the loss of cytoplasm, the plasma membrane (arrowheads) remains closely associated with the cell wall but is undulating in profile. The appressorial wall is composed of a moderately electron-opaque inner layer (iw) and a highly electron-opaque outer layer (ow), surrounded by extracellular matrix (ecm). Bar, 0.2 μm.

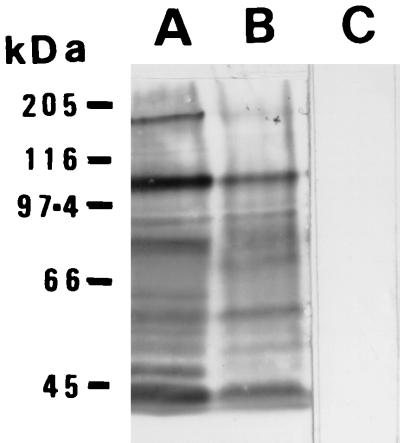

Cell wall glycoproteins from purified appressoria were separated by SDS-PAGE and compared with wall proteins from C. lindemuthianum mycelium using MAb UB22 (14). This antibody recognizes a carbohydrate epitope on surface glycoproteins, and the Western blots show clear differences between the walls of appressoria and mycelium (Fig. 3). In particular, there are glycoproteins with apparent sizes of 200, 75, and 48 kDa that are specific to or present at higher levels in the appressorial samples.

FIG. 3.

Western blots of cell wall glycoproteins from purified appressoria (A) and mycelium (B and C) of C. lindemuthianum probed with MAb UB22 (A and B) or UBIM22 (C).

DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to develop a method for the purification of C. lindemuthianum appressoria that could subsequently be used for analysis of cell surface components. We obtained purified appressoria with sufficient yield to allow biochemical studies to be performed. To our knowledge there are no other published reports demonstrating comparable enrichment of these fungal infection structures. The appressoria purified by the IMS procedure lack cytoplasm and therefore cannot be used for RNA or DNA isolation. However, as demonstrated above, they are clearly valuable for biochemical analysis of the cell wall and plasma membrane and for studies on wall-membrane interactions and potentially can be used to raise further antibodies and for studies using proteomics to compare different fungal infection structures. MAb UB31 specifically labels the appressoria of several other Colletotrichum species tested, including C. destructivum, C. magna, and C. orbiculare (results not shown), and IMS could therefore be used to purify appressoria for comparative studies.

Previously, lectins and MAbs have been used to study and make comparisons between the cell surfaces of C. lindemuthianum infection structures (6, 12, 13). Results have shown that the cell walls and extracellular matrices around germ tubes and appressoria have many similarities, but these differ from those of conidia and intracellular hyphae. In the present study we used MAb UB22 to compare cell surfaces of purified appressoria with mycelium. MAb UB22 recognizes a carbohydrate epitope on surface glycoproteins, and earlier work showed that it also bound several components of the mycelial wall (14). The results described above using Western blotting of purified appressorial samples with UB22 show that the appressorial cell walls are highly differentiated in comparison with mycelium, and we attribute this difference to the specialized functions of appressoria.

In previous studies a plasma membrane glycoprotein specific to C. lindemuthianum appressoria was identified using MAb UB27 (16). Detergent extraction of the appressorial membranes showed that the glycoprotein had the characteristics of an integral membrane protein, but a proportion of the glycoprotein was insoluble, suggesting attachment to the fungal wall (16). The ultrastructural studies on IMS-purified appressoria showed retention of the appressorial plasma membrane within the empty cells, supporting the hypothesis that this membrane is tightly cross-linked to the appressorial cell wall. Clearly, these purified appressoria can be used for further studies on plasma membrane-wall interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IACR-Long Ashton Research Station receives grant-aided support from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council of the United Kingdom. This work was supported by a BBSRC Link award (grant no. P01439) and a BBSRC CASE studentship to K. A. Hutchison and was carried out under authority given by MAFF license PHF 870B/405/33.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cantrill L C, Deverall B J. Isolation of haustoria from wheat leaves infected by the leaf rust fungus. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1993;42:337–343. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark J S C, Spencer-Phillips P T N. Isolation of endophytic mycelia by enzymic maceration of Peronospora-infected leaves. Mycol Res. 1990;94:283–287. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gil F, Gay J L. Ultrastructural and physiological properties of the host interfacial components of haustoria of Erysiphe pisi in vivo and in vitro. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1977;10:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn M, Mendgen K. Isolation by ConA binding of haustoria from different rust fungi and comparison of their surface qualities. Protoplasma. 1992;170:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansel T T, Pound J D, Pilling D, Kitas G D, Salmon M, Gentle T A, Lee S S, Thompson R A. Purification of human blood eosinophils by negative selection using immunomagnetic beads. J Immunol Methods. 1989;122:97–103. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes H B, Carzaniga R, Rawlings S L, Green J R, O'Connell R J. Spore surface glycoproteins of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum are recognized by a monoclonal antibody which inhibits adhesion to polystyrene. Microbiology. 1999;145:1927–1936. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-8-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchison K A, O'Connell R J, Pain N A, Green J R. A bean epicuticular glycoprotein is present in the extracellular matrices around infection structures of the anthracnose fungus, Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. New Phytol. 1996;134:579–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1996.tb04923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang C-S, Flaishman M A, Kolattukudy P E. Cloning of a gene expressed during appressorium formation by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and a marked decrease in virulence by disruption of this gene. Plant Cell. 1995;7:183–193. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamboy J S, Staples R C, Hoch H C. Superoxide dismutase: a differentiation protein expressed in Uromyces germlings during early appressorium development. Exp Mycol. 1995;19:284–296. doi: 10.1006/emyc.1995.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendgen K, Deising H. Tansley review no. 48: infection structures of fungal plant pathogens—a cytological and physiological evaluation. New Phytol. 1993;124:193–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Connell R J, Bailey J A, Richmond D V. Cytology and physiology of infection of Phaseolus vulgaris by Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1985;27:75–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connell R J, Pain N A, Bailey J A, Mendgen K, Green J R. Use of monoclonal antibodies to study differentiation of Colletotrichum infection structures. In: Nicole M, Gianinazzi-Pearson V, editors. Histology, ultrastructure and molecular cytology of plant-microorganism interactions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1996. pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Connell R J, Pain N A, Hutchison K A, Jones G L, Green J R. Ultrastructure and composition of the cell surfaces of infection structures formed by the fungal plant pathogen Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. J Microsc. 1996;181:204–212. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pain N A, O'Connell R J, Bailey J A, Green J R. Monoclonal antibodies which show restricted binding to four Colletotrichum species: C. lindemuthianum, C. malvarum, C. orbiculare and C. trifolii. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1992;40:111–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pain N A, Green J R, Gammie F, O'Connell R J. Immunomagnetic isolation of viable intracellular hyphae of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum (Sacc. & Magn.) Briosi & Cav. from infected bean leaves using a monoclonal antibody. New Phytol. 1994;127:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pain N A, O'Connell R J, Green J R. A plasma membrane-associated protein is a marker for differentiation and polarization of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum appressoria. Protoplasma. 1995;188:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotman B, Papermaster B W. Membrane properties of living mammalian cells as studied by enzymatic hydrolysis of fluorogenic esters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;55:134–141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharpe P T. Methods of cell separation. In: Burdon R H, van Knippenberg P H, editors. Laboratory techniques in biochemistry and molecular biology. Vol. 18. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takano Y, Kubo Y, Kuroda I, Furusawa I. Temporal transcriptional patterns of three melanin biosynthesis genes, PKS1, SCD1, and THR1, in appressorium-differentiating and nondifferentiating conidia of Colletotrichum lagenarium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:9–16. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.351-354.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiburzy R, Martins E M F, Reisener H J. Isolation of haustoria of Puccinia graminis f.sp. tritici from wheat leaves. Exp Mycol. 1992;16:324–328. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugelstad J, Berge A, Ellingsen T, Aune O, Kilaas L, Nilsen T M, Schmid R, Stenstad P, Funderud S, Kvalheim G, Nustads K, Lea T, Vartdal F. Monosized magnetic particles and their use in selective cell separation. Macromol Chem. 1988;17:177–211. [Google Scholar]