Abstract

Purpose

Adolescents might be susceptible to the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown. We assessed changes in mental wellbeing throughout the first year of the pandemic and compared these with prepandemic levels.

Methods

This five-wave prospective study among Dutch adolescents aged 12–17 years used data collected before the pandemic (n = 224) (T0), in May (T1), July (T2), and October 2020 (T3), and in February 2021 (T4). Generalized estimating equations were used to assess the association between stringency of the lockdown with mental wellbeing.

Results

Adolescents had a lower life satisfaction during the first full lockdown (T1) [adjusted β: −0.36, 95% confidence interval (CI): −0.58 to −0.13], during the partial lockdown (T3) (adjusted β: −0.37, 95% CI: −0.63 to −0.12), and during the second full lockdown (T4) (adjusted β: −0.79, 95% CI: −1.07 to −0.52) compared to before the pandemic (T0). Adolescents reported more internalizing symptoms during only the second full lockdown (T4) (adjusted β: 2.58, 95% CI: 0.41–4.75). During the pandemic [at T1 (adjusted β: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.20–0.38), T2 (adjusted β: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.26–0.46), T3 (adjusted β: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.22–0.45), and T4 (adjusted β: 0.20, 95% CI: 0.07–0.34)], adolescents reported a better psychosomatic health, partly attributable to less trouble falling asleep (p < .01).

Discussion

The COVID-19 lockdown measures have had both a negative and positive impact on mental wellbeing of Dutch adolescents. However, mental wellbeing was most impacted during the second full lockdown compared to before the pandemic.

Keywords: Adolescent, COVID-19 pandemic, Mental wellbeing

Implications and Contribution.

The COVID-19 lockdown measures had a negative impact on adolescent life satisfaction, but a positive impact on psychosomatic health. Mental wellbeing was lowest during the second full lockdown compared to before: life satisfaction was at its lowest, more internalizing symptoms were reported, and psychosomatic health increased the least during this period.

All around the world, school closures, quarantining, and social distancing have been key in governmental attempts to reduce the transmission of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome - Corona Virus- 2, hospitalizations, and death in the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2]. As a result of these restriction measures, billions of people worldwide face unprecedented periods of social isolation and stress [2,3]. Adolescents might be particularly susceptible to the social effects of these lockdown measures [3,4]. Adolescence is not only marked as a time period in which numerous mental health disorders emerge for the first time, but also as a formative period for neurocognitive and social developments [[5], [6], [7]]. For instance, young people spend increasingly more time with their peers and are more influenced by peers than by adults in their social decision making, feeling accepted and rejected, and getting approval [4,6,8]. Friendships are therefore instrumental aspects of adolescent mental wellbeing [9]. Social face-to-face contacts in particular are not only actively discouraged by the COVID-19 restriction measures [2], but also limited due to the transition to online education. These aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, among many others, might jeopardize adolescent mental wellbeing.

Longitudinal data are required to better understand the effects of lockdown measures on mental wellbeing, preferably including baseline measures assessed prior to COVID-19 [3,10]. Several longitudinal studies reported on adolescent mental wellbeing in response to COVID-19 lockdown measures and have shown that anxiety and depressive symptoms increased, and life satisfaction deteriorated during the first full lockdown in youth (8–18 years) living in the Netherlands, Australia, and North America [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. A large international collaborative effort using data of 12 longitudinal studies (10 performed in the USA, 1 in the Netherlands, and 1 in Peru) identified an increase in depressive symptoms in adolescents (mean age 15.4 years) [15]. However, it is also known that although life satisfaction of Dutch adolescents (mean age 15.5 years) decreased, their internalizing symptoms did not change, and psychosomatic health even improved during the pandemic, compared to baseline [16]. To date, to our knowledge, no studies have taken multiple repeated assessments of adolescent mental wellbeing during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and concomitantly the stringency of the lockdown, into account.

In this five-wave prospective longitudinal study among Dutch adolescents, we assessed changes in mental wellbeing throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and compared these with prepandemic levels (T0). The stringency of the lockdown was significantly different at the four follow-up assessments (T1–T4), due to diverse implemented restriction measures. Additionally, we explored whether there was a differential change in mental wellbeing between boys and girls, as girls have incidence of mental health problems during adolescence compared to boys [17].

Methods

Study design and study population, baseline (T0)

Data were obtained from an ongoing population-based birth cohort study, named WHISTLER (WHeezing Illness STudy in LEidsche Rijn) [16,18]. Between 2001 and 2012 newborns were recruited from the general population in a fairly affluent and newly built suburb of Utrecht, the Netherlands. The participants have been followed at age of 3, 5, and 8 years. In March 2019, we invited the 12- to 16-year-old WHISTLER participants to complete a questionnaire and undergo a health assessment. One of the primary aims was to assess their mental wellbeing during adolescence. Due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to stop this follow-up round. Up to then 224 adolescents completed the questionnaires (52.7% girls, mean age 14.82 years). This was indicated as T0. These adolescents were invited to complete the follow-up questionnaires (T1–T4) during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the questionnaires were sent in May (T1), July (T2), and October 2020 (T3), and February 2021 (T4). The participants were able to complete the questionnaire within 1 month. The analysis of adolescent mental wellbeing at T0 and T1 has been published elsewhere [16].

Ethical approval for WHISTLER (file number: NL66918.041.18) was obtained from the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht. Participants and their parents or legal guardians provided active written informed consent.

Follow-up: assessments throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (T1–T4)

The Dutch restrictive measures varied considerable in the first year of the pandemic, and our follow-up assessments (T1–T4) captured four different phases of government policy. To more objectively rate the stringency of the restrictions and increase comparability with other countries, we used a national lockdown stringency index based on a composite measure of nine different lockdown measures: the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT). The index has values from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest) [19]. This OxCGRT identified that the stringency of the Dutch lockdown was 78.70 around T1, during the first full lockdown; 39.81 around T2, during the period that this first full lockdown was eased; 62.04 around T3, a less restrictive “partial” lockdown; and 78.70–82.41 around T4, a second full lockdown, respectively [19,20]. This indicates that T4 was the most stringent lockdown.

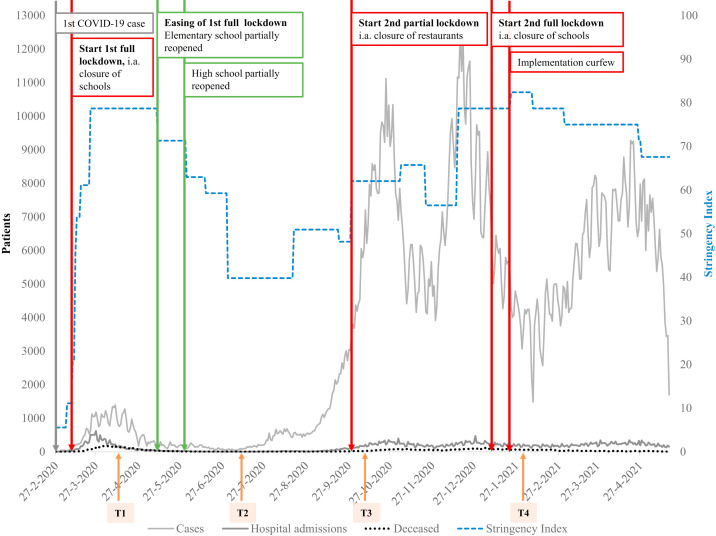

Figure 1 shows the timeline of COVID-19 cases, hospital admissions, deaths, and stringency index in the Netherlands, as well as the timing of sending the questionnaires and timing of introduction and easing of lockdown measures. For a full summary of when and which lockdown measures were introduced and eased, please refer to Appendix A.

Figure 1.

Timeline of COVID-19 cases, hospital admissions, deceased, and stringency index in the Netherlands. Introduction and easing of lockdown measures, and timing of sending the questionnaires. Orange arrows denote sending questionnaires at T1, T2, T3, and T4; brown arrows denote implementing restrictions; and green arrows denote easing of measures. T0 = before the COVID-19 lockdown; T1 = first full lockdown (assessment April 18, 2020); T2 = first full lockdown eased (assessment July 18, 2020); T3 = partial lockdown (assessment October 18, 2020); T4 = second full lockdown (assessment February 2, 2021).

Mental wellbeing assessments

Mental wellbeing was assessed using the following three indicators: life satisfaction, internalizing symptoms, and psychosomatic health using respectively the Cantril ladder [21,22], the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) [23], and the Health Behavior in School-aged Children Symptom Checklist (HBSC-SCL) 2017 [24]. To investigate whether mental wellbeing changed from baseline to follow-up, we assessed the same instruments at each follow-up time period (T1–T4). The specifics of these instruments are described in short below; please refer to Appendix B for full details.

Life satisfaction was assessed with the Cantril ladder, a valid and reliable instrument of life satisfaction in adolescence [21,22,25]. The Cantril ladder includes one question “Looking at the past 3 months, how do you feel about your life?” and possible answers range from 0 to 10 (10 = best possible life) [21,22,25].

Internalizing symptoms, i.e., the severity of self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms, were assessed using the RCADS. The RCADS is based on anxiety disorders and depression from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV [23]. The questionnaire contains 47 items, which are rated by respondents on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “never” to 3 “always.” In our study, the correlation between the subdomains “anxiety” and “major depressive disorder” was r(Pearson) > 0.7 across waves; therefore, we analyzed these subdomains together as internalizing symptoms. Raw scores were converted into gender and age-normed T-scores using the syntax from the RCADS-developer (based on US population) [26] and evaluated as a continuous score.

Psychosomatic health complaints are symptoms that are often related to psychosocial factors, such as stress [27]. Psychosomatic health was measured with HBSC-SCL and expressed in a mean score of 10 symptoms, such as having a headache, being nervous, or feeling dizzy [24]. The higher the mean score, the better psychosomatic health one is experiencing, meaning that one is feeling little stress. The HBSC-SCL has good psychometric properties and has also been validated in Dutch [24,28].

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of the study population. Due to correlations among repeated measures of outcomes in the same individual, regression models using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an identity link function were used to assess the association between time of assessment (stringency of the lockdown) with repeated measures of mental wellbeing (life satisfaction/internalizing symptoms/psychosomatic health; each outcome measure analyzed individually). While using the GEE, we choose for an independent correlation structure which enables the GEE to handle time-dependent variables (such as age) to change over time [29]. Associations with the outcomes were expressed as differences (β’s), with “no lockdown measures” (T0) as the reference category. As a secondary analysis, we tested for interactions between gender and time of assessment to analyze whether boys’ and girls’ mental wellbeing changed differentially over time. Additionally, McNemar’s chi-squared tests were used to analyze whether the frequency of occurrence of psychosomatic symptoms differed between baseline and follow-up assessments.

We used multiple imputation, producing 25 sets of imputed data, with predictive mean matching to impute missing covariates and outcome measures, incorporating data on potential confounders (age and gender) and the outcomes [30]. We imputed the data for all participants who completed baseline (T0). Moreover, as auxiliary variables are considered to improve the quality of imputation and therefore might reduce bias, we included two auxiliary variables: ethnicity and level of education of the adolescent [31,32]. Analysis on multiple imputation increases precision of the estimates and reduces the potential bias introduced by missing data [30]. Therefore, it was chosen as the primary analysis for the GEE. The results from the complete case analysis are shown in Appendix C.

We adjusted the GEE for a priori selected potential confounders based on directed acyclic graphs: gender (male/female) and age. A p-value <.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were done with SPSS 26.0.

Results

Study population

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population at the five assessment waves (T0–T4). Of the 224 participants who completed their questionnaire at baseline, 158 participants (70.5%) completed it at T1, 149 participants (66.5%) at T2, 152 participants (67.9%) at T3, and 128 participants (57.1%) at T4. Data on mental wellbeing were available for at least 2 of the 5 assessments for 186 (83%) participants, and for 4 of the 5 assessments for 132 (59%) participants. Of the 224 adolescents at T0, 95.1% had a Western ethnicity, and 93.3% had a parent with a high (university) or intermediate (vocational) level of education. Girls and adolescents with a higher level of education were more willing to complete the follow-up questionnaires (Table 1). In general, no differences with respect to the outcome measures were observed between the participants who completed the follow-up questionnaire and participants who did not. However, girls were more likely to complete the questionnaires at all follow-up rounds (T1, p = .002; T2, p = .004; T3, p = .012; T4, p = .000) compared to boys. In addition, adolescents with higher levels of education completed follow-up questionnaires more frequently at T2 (p = .017) and T3 (p = .005).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the WHISTLER cohort study samples that completed the questionnaires before and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic

| Demographics | T0 (n = 224) | T1 (n = 158) | T2 (n = 149) | T3 (n = 152) | T4 (n = 128) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yearsa, mean (SD) | 14.82 (1.24) | 15.53a (1.25) | 15.76 (1.28) | 16.01 (1.28) | 16.30 (1.28) |

| Gender (%) | |||||

| Girl | 118 (52.68) | 94 (59.49) | 88 (59.06) | 87 (57.23) | 82 (64.06) |

| Educational level of the adolescentb (%) | |||||

| Primary school | 3 (1.34) | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.24) | 3 (1.97) | 2 (1.56) |

| Low | 52 (23.21) | 34 (21.52) | 27 (18.12) | 32 (21.05) | 24 (18.75) |

| Intermediate | 63 (28.13) | 39 (24.68) | 33 (22.15) | 30 (19.74) | 28 (17.72) |

| High | 101 (45.09) | 79 (50.00) | 75 (50.34) | 75 (49.34) | 64 (50.00) |

| Special education | 8 (3.57) | 4 (2.53) | 4 (2.68) | 3 (1.97) | 3 (2.34) |

| Stringency index of lockdown | NA | 78.70 | 39.81 | 62.04 | 78.80–82.41 |

NA = not applicable; SD = standard deviation; T0 = before the COVID-19 lockdown; T1 = first full lockdown (assessment April 18, 2020); T2 = first full lockdown eased (assessment July 18, 2020); T3 = partial lockdown (assessment October 18, 2020); T4 = second full lockdown (assessment February 2, 2021); WHISTLER = WHeezing Illness STudy in LEidsche Rijn.

Calculated based on completion date of follow-up questionnaire.

Low: pre–vocational secondary education; intermediate: higher general secondary education or intermediate vocational education; high: preuniversity education, higher vocational education and university.

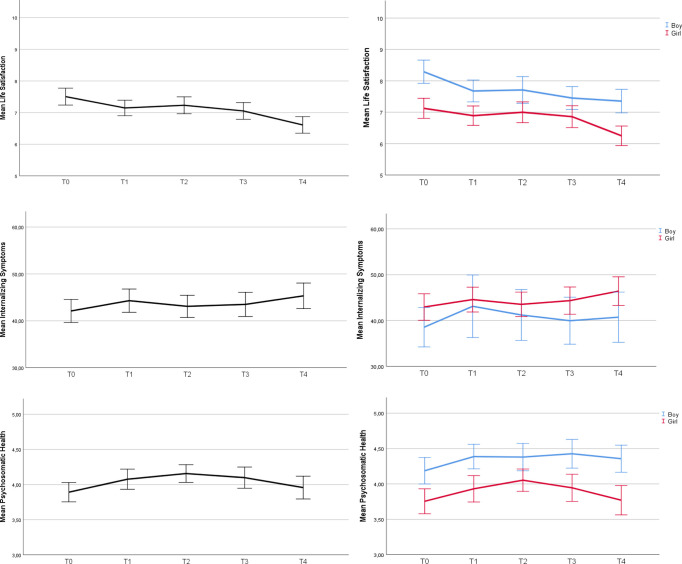

Figure 2 shows both the overall mean of the entire sample, as well as the mean stratified by gender for all three outcome measures per assessment (T0–T4). This illustrates the trend over time The exact values of the outcome measures are described in Appendix D.

Figure 2.

Life satisfaction, internalizing symptoms, and psychosomatic health before and throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic for the entire sample and stratified by gender. T0 = before the COVID-19 lockdown; T1 = first full lockdown (assessment April 18, 2020); T2 = first full lockdown eased (assessment July 18, 2020); T3 = partial lockdown (assessment October 18, 2020); T4 = second full lockdown (assessment February 2, 2021).

Associations between time of assessment (lockdown stringency) and mental wellbeing

We used multiple imputation to impute missing covariate and outcome data. The effect estimates for results based on the multiple imputation dataset were comparable to the complete case analysis. The precision was generally improved as the confidence intervals (CIs) were slightly smaller. We considered the imputed results as the primary results and present the complete case results in Appendix C.

Adolescents had a significantly lower life satisfaction during the first full lockdown (T1) (adjusted β: −0.36, 95% CI: −0.58 to −0.13), during the partial lockdown (T3) (adjusted β: −0.37, 95% CI: −0.63 to −0.12), and during the second full lockdown (T4) (adjusted β: −0.79, 95% CI: −1.07 to −0.52) compared to before the pandemic (Table 2 ). At the time that the first full lockdown was eased (T2), no significant change in life satisfaction was reported (adjusted β: −0.19, 95% CI: −0.42 to 0.05). There were differential changes in life satisfaction over time between boys and girls (p interaction = .015); boys’ life satisfaction decreased at a faster rate over time than girls’ life satisfaction.

Table 2.

Life satisfaction, internalizing symptoms, and psychosomatic health: differences when measured before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (reference), compared to assessments throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic

| Time of assessment | Crude β | (95% CI) | Adj β | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfactiona | ||||

| T0: before COVID-19 pandemic | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| T1: first full lockdown | −0.47 | (−0.68 to −0.26) | −0.36 | (−0.58 to −0.13) |

| T2: first full lockdown eased | −0.33 | (−0.55 to −0.12) | −0.19 | (−0.42 to 0.05) |

| T3: partial lockdown | −0.56 | (−0.78 to −0.34) | −0.37 | (−0.63 to −0.12) |

| T4: second full lockdown | −1.02 | (−1.25 to −0.80) | −0.79 | (−1.07 to −0.52) |

| Internalizing symptomsb | ||||

| T0: before COVID-19 pandemic | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| T1: first full lockdown | 1.18 | (−0.15 to 2.50) | 0.96 | (−0.58 to 2.50) |

| T2: first full lockdown eased | 0.95 | (−0.37 to 2.27) | 0.66 | (−1.00 to 2.31) |

| T3: partial lockdown | 1.27 | (−0.05 to 2.58) | 0.90 | (−0.90 to 2.69) |

| T4: second full lockdown | 3.04 | (1.50–4.58) | 2.58 | (0.41–4.75) |

| Psychosomatic healthc | ||||

| T0: before COVID-19 pandemic | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| T1: first full lockdown | 0.25 | (0.17–0.32) | 0.29 | (0.20–0.38) |

| T2: first full lockdown eased | 0.30 | (0.22–0.39) | 0.36 | (0.26–0.46) |

| T3: partial lockdown | 0.26 | (0.17–0.35) | 0.33 | (0.22–0.45) |

| T4: second full lockdown | 0.12 | (0.01–0.22) | 0.20 | (0.07–0.34) |

The values are based on imputed data.

Adj = adjusted (adjusted for gender and age); CI = confidence interval; T0 = before the COVID-19 lockdown; T1 = first full lockdown (assessment April 18, 2020); T2 = first full lockdown eased (assessment July 18, 2020); T3 = partial lockdown (assessment October 18, 2020); T4 = second full lockdown (assessment February 2, 2021).

A higher score indicates a higher life satisfaction.

A higher score indicates more severe self-reported internalizing symptoms.

A higher score indicates experiencing psychosomatic complaints less frequently.

Adolescents reported significantly more internalizing symptoms during the second full lockdown only (T4; adjusted β: 2.58, 95% CI: 0.41–4.75), compared to internalizing symptoms assessed before the beginning of the pandemic (T0). During the first full lockdown (T1) (adjusted β: 0.96, 95% CI: −0.58 to 2.50), during the easing of the first full lockdown (T2) (adjusted β: 0.66, 95% CI: −1.00 to 2.31), and during the partial lockdown (T3) (adjusted β: 0.90, 95% CI: −0.90 to 2.69) no significant change in internalizing symptoms was reported (Table 2). Secondary analyses did not reveal a differential change in internalizing symptoms at the various assessments between boys and girls (p interaction = .46).

Throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic [at T1 (adjusted β: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.20–0.38), T2 (adjusted β: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.26–0.46), T3 (adjusted β: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.22–0.45), and T4 (adjusted β: 0.20, 95% CI: 0.07–0.34)], adolescents reported a significantly better psychosomatic health than before the start of the pandemic (T0) (Table 2). Secondary analyses did not reveal a differential change in psychosomatic health at the various assessments between boys and girls (p interaction = .29).

Contrary to our expectations, psychosomatic health was better throughout the first year of the pandemic than before. Therefore, in an exploratory a posteriori analysis, we assessed changes in specific psychosomatic symptoms which are presented in Appendix E. We identified that adolescents were able to fall asleep more easily (p < .01) throughout the first year of the pandemic at all follow-up rounds. In addition, adolescents also experienced other specific symptoms less frequently at some follow-up rounds (Appendix E).

Discussion

This is the first study that considered multiple repeated assessments of adolescent mental wellbeing, both prepandemic as well as during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (OxCGRT stringency index: T1: 78.80; T2: 39.81; T3: 62.04; and T4: 78.80–82.41). Our five-wave prospective cohort study among Dutch adolescents yielded an interesting picture of change on mental wellbeing throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Life satisfaction decreased during the first and second full lockdowns as well as the partial lockdown, compared to before the pandemic. Notably, life satisfaction decreased most at the second full lockdown in February 2021. Moreover, boys’ life satisfaction decreased at a faster rate than girls during the pandemic compared to the prepandemic baseline. Adolescents only reported more internalizing symptoms, reflecting anxiety and depression symptoms, during the second full lockdown. Interestingly, throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, adolescents reported significantly better perceived psychosomatic health. Exploratory analyses indicated that this improvement is partly attributable to being able to fall asleep more easily.

Previous longitudinal studies assessing mental wellbeing during and before the pandemic can be used to benchmark our findings, while keeping in mind that these studies did not assess mental wellbeing during the entire first year of the pandemic. Similar to our study, a deterioration in life satisfaction during the pandemic was observed in Australian adolescents (aged 13–19 years; stringency index: 65.74–69.44) and Dutch adolescents (aged 10–20 years; stringency index: 78.80–65.74) [11,12,14,16]. In our study, we observed that life satisfaction seems to be correlated with the stringency level of the lockdown: when the stringency index was high life satisfaction decreased, and vice versa. However, we did not observe this pattern when comparing the absolute values of the stringency index between countries, as Australian adolescents experienced a lower life satisfaction, but Chinese youth did not: the stringency index of the Australian lockdown was substantially lower compared to that of the Chinese lockdown. Therefore, focusing on a change in mental wellbeing over time within a specific context seems to be preferable over comparing adolescent mental wellbeing between countries while using the stringency index. However, future research could focus on disentangling which aspects of the different national lockdowns affect mental wellbeing.

Our sample only reported significantly more internalizing symptoms during the second full lockdown (stringency index: 78.80–82.41). Australian youth (8–18 years old) reported more anxiety and depressive symptoms in the initial phase of the pandemic [12] (stringency index: 65.74–69.44), as did adolescents (aged 14–17) living in the USA (stringency index: 67.13–72.69) [13,33]. Nonetheless, the average scores of the youth living in the USA did not reach the clinical threshold for anxiety disorders and depression [13,26]. Additionally, Barendse et al. [15] showed, especially for bi- or multiracial adolescents, an increase in depressive symptoms in an international sample of adolescents (mean age 15.4 years). Therefore, it remains important to monitor internalizing symptoms and to evaluate potentially vulnerable subgroups, especially when the stringency level of the pandemic increases. Some studies identified vulnerable subgroups: Cohen et al. [34] showed that healthy adolescents experienced more anxiety and depression during the pandemic compared to before, while adolescents with early life stress who were thought of being at particular risk did not. Additionally, Zijlmans et al. [35] showed that youth (aged 8–18 years) with a (chronic) somatic condition experienced a better mental wellbeing compared to their healthy peers. However, youth with pre-existing mental problems had a lower mental wellbeing than youth with a somatic condition or healthy peers [35]. These studies suggested that some youth with adverse life events seemed to be more resilient than healthy adolescents. Therefore, future studies could examine which risk and resilience factors might be of influence on adolescent mental wellbeing changes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interestingly, reported psychosomatic health of adolescents increased during the pandemic. Although statistically significant, it is questionable whether this improvement was also clinically relevant. As psychosomatic health was expressed in a mean score of 10 symptoms, the direct impact on daily life, except for experiencing less stress in general, was difficult to determine. However by assessing changes in specific psychosomatic symptoms, we identified that the improved psychosomatic health was partly attributable to falling asleep more easily during the pandemic compared to before. Other studies reported that youth more often slept 8 hours or longer during the COVID-19-related lockdown compared to their sleep rhythms prior to the pandemic [11,36,37], and that bedtime and wake times shifted to later hours [37]. During puberty, hormonal changes alter the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep, with the result that adolescents tend to stay up and sleep in [38]. The altered sleep rhythm might conflict with early school start times. As a result, chronic sleep loss is a common phenomenon for adolescents [39]. Due to school closures, online education (T1, T3, and T4), and summer holidays (T2), it might be conceivable that our sample of adolescents were able to shift their bedtime and wake times to later hours, resulting in better syncing of their sleep-wake behavior with their circadian rhythm. Multiple studies have shown that delaying school start times led to better alignment of circadian system and therefore resulted in better sleep quantity and quality. As a consequence, mental health issues decreased, and physical health and academic performances improved [40,41]. Therefore, it was previously recommended that national governments may consider possibilities that could enhance the alignment of adolescent sleep-wake behavior with their circadian rhythm, e.g., by delaying school start times [16].

It is well known that adolescent girls have lower mental wellbeing on average than boys [42]. Also in our study, boys scored better than girls on all three indicators of mental wellbeing. However, our results showed that boys’ life satisfaction deteriorated during the pandemic, while Magson et al. [12] reported that a decline in life satisfaction among adolescents (13–16 years) during the pandemic was particularly pronounced among girls. We can only speculate as to why only boys showed a deterioration in life satisfaction. Lockdown measures actively discouraged group gatherings. When focusing on social interactions, boys are more likely to hang out in groups, whereas girls tend to spend more time in friendship dyads [43,44]. Therefore the measures might have affected boys’ life satisfaction more than girls’. Also, girls are more likely than boys to communicate with friends online [45]. Research showed that adolescents had higher anxiety and depression scores during the pandemic compared to before, when they experienced a poorer connection with friends and family [46]. Keeping in touch with friends online during the pandemic may reduce the impact of lockdown measures on girls’ mental wellbeing. Finally, girls might have more communication tools to cope with changes due to the lockdown measures because they are, in general, more likely to ask for help, have more positive connections to their parents, and communicate more than boys [47]. Future research could focus on why gender matters when it comes to changes in life satisfaction during this pandemic.

Our study reported an interesting picture of change on mental wellbeing throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. By (partly) maintaining their mental wellbeing, our participants showed that they functioned resiliently during the pandemic. In the literature, it is described that supportive social environment like parent support makes adolescents more able to respond resiliently to adversity [9,48]. In 2017, the HBSC study, conducted in 45 European countries plus Canada, found that Dutch adolescents were remarkably positive about their relationship with parents [45,49]. Of the Dutch 15-year-olds, 81% and 90% reported that they can easily talk to their father or mother about their worries, respectively. In other countries, the average was much lower: 65% (father) and 80% (mother) [45]. Although these data were collected in 2017, these results give an indication on how adolescents might experience being in lockdown at home with their parents. This gives them a good starting position regarding their mental wellbeing for the crisis. Future research may allow researchers to confirm these protective factors.

Nonetheless, adolescents’ mental wellbeing changed the most during the longer lasting second full lockdown (T4) compared to prepandemic levels: life satisfaction was lowest and more internalizing symptoms were reported. During this lockdown, schools were closed for the second time during the pandemic. A recent systematic review showed that during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health issues among children and adolescents (mainly anxiety and depressive symptoms) and adverse health behaviors (such as decreased physical activity and increased screen time) were associated with school closures and the social lockdown [50]. Nonetheless, it was not possible to disentangle the effects of school closures from broader social lockdown measures [50].

A particular strength of this study is the longitudinal prospective design with five time waves of data collection, including a prepandemic baseline assessment. The follow-up assessments included the initial and also the consecutive COVID-19 phases during the first year of the pandemic taking multiple lockdowns with a different stringency index into account. Multiple indicators of mental wellbeing were assessed, with internationally renowned instruments. Some limitations deserve mention. Despite the longitudinal design, we cannot determine a causal relationship between the stringency of the lockdown and adolescent mental wellbeing. Mental wellbeing was most impacted during the second full lockdown. Moreover, also the stringency index was at its highest at that point of time: 78.70–82.41 [19,20]. However, the duration of the lockdown might be another driver of these negative outcomes, since participants had already been in a lockdown for over 3.5 months. The independent effect of the duration versus the stringency of the lockdown could not be disentangled. Additionally, factors unrelated to the pandemic, such as seasons and school breaks, might also have influenced the associations. For example, certain affective disorders are more present in particular seasons; adolescents especially suffer from seasonal affective disorder in winter, resulting in feeling more irritable, fatigue, and sad [51]. Seasonal affective disorder could also have had an effect on our outcome measures.

Moreover, the participants of the WHISTLER birth cohort were recruited from the general population living in a fairly affluent, and newly built suburb in the Netherlands [18]. As a result, adolescents with parents with a lower educational background and a non-Western migration background were underrepresented. This limits the generalizability of our results to populations with different educational, ethnic, and/or cultural backgrounds.

In cohort studies, loss-to-follow-up is a common phenomenon which can lead to attrition bias. For all three outcome measures, there was no significant difference between responders and nonresponders at baseline. However, girls and adolescents with higher levels of education were more likely to complete the questionnaires at follow-up rounds. Because girls scored lower on all three outcomes compared to boys, a lower mental wellbeing might have been observed than in a representative sample. Therefore, attrition bias might have been introduced by loss of boys completing the questionnaire in the follow-up rounds. Adolescent education level did not affect mental wellbeing, and therefore loss of follow-up of adolescents with lower levels of education did not introduce attrition bias.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most profound events for society and citizens in the last decades. Ongoing longitudinal research will grant researchers to appreciate its lasting impact with regard to mental wellbeing. Moreover, such research may allow researchers to identify why certain subgroups of youth were doing well or were doing poorly before, during, and in the aftermath of the pandemic. Due to co-occurrence of other factors that might have affected adolescent mental wellbeing, the independent effect of the lockdown severity on our outcome measures could not be established. To gain better insight in the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental wellbeing, combining the results of various studies concerning this topic would be promising. Furthermore, our results suggest that further research is warranted on the relationship between sleep and mental wellbeing, and on interventions or policy (e.g., school starting time) changes that enhance better syncing of adolescent sleep-wake behavior with their circadian rhythm.

In conclusion, this prospective, longitudinal study among Dutch adolescents identified that the COVID-19 lockdown measures mainly have had a negative impact on adolescent life satisfaction, but have had a positive impact on psychosomatic health. Additionally, mental wellbeing changed most during the longer lasting second full lockdown when compared to prepandemic levels: life satisfaction was at its lowest, more internalizing symptoms were reported, and psychosomatic health increased the least at this period in time.

Acknowledgments

Contributors’ Statement: van der Laan conceptualized and drafted the initial manuscript, carried out the initial analyses, and revised the manuscript. van der Ent is PI of the WHISTLER study since the start of the study in 2002. He contributed to the design and follow-up of the study and coordinated and supervised data collection and data management. He also reviewed and revised the manuscript. Nijhof conceptualized the initial manuscript. Finkenauer, Lenters, and van Harmelen gave advice and support with the analyses. Finkenauer, Lenters, Nijhof, van Harmelen, and van der Ent conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.06.006.

Funding Sources

All phases of this study were supported by Stichting Tetri. Tetri grant number: 1617121.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Haug N., Geyrhofer L., Londei A., et al. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4:1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19). World health Organization. 2020. www.who.int Available at:

- 3.Wade M., Prime H., Browne D. Why we need longitudinal mental health research with children and youth during (and after) the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113143. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orben A., Tomova L., Blakemore S. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:634–640. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blakemore S.-J., Mills K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakemore S. The art of medicine adolescence and mental health. Lancet. 2019;393:2030–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knoll L.J., Magis-Weinberg L., Speekenbrink M., Blakemore S.J. Social influence on risk Perception during adolescence. Psychol Sci. 2015;26:583–592. doi: 10.1177/0956797615569578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Harmelen A.L., Kievit R.A., Ioannidis K., Al E. Adolescent friendships predict later resilient functioning across psychosocial domains in a healthy community cohort. Psychol Med. 2017;47:2312–2322. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J.J., Bao Y., Huang X., et al. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;4:347–349. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munasinghe S., Sperandei S., et al. The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among Australian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magson N.R., Freeman J.Y.A., Rapee R.M., et al. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50:44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breaux R., Dvorsky M.R., Marsh N.P., et al. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62:1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green K.H., van de Groep S., Sweijen S.W., et al. Mood and emotional reactivity of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Short-term and long-term effects and the impact of social and socioeconomic stressors. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11563. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90851-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barendse M., Flannery J., Cavanagh C., et al. Longitudinal change in adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international collaborative of 12 samples. Preprint. 2021;1:7–8. doi: 10.1111/jora.12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Laan S., Finkenauer C., Lenters V., et al. Gender-specific changes in life satisfaction after the COVID-19-related lockdown in Dutch adolescents: A longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Droogenbroeck F., Spruyt B., Keppens G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:6. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1591-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katier N., Uiterwaal C.S.P.M., De Jong B.M., et al. The Wheezing Illnesses study Leidsche Rijn (WHISTLER): Rationale and design. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:895–903. doi: 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000040530.98310.0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blavatnik School of Government COVID-19: Stringency index. www.bsg.ox.ac.uk. 2020. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/covid-19-government-response-tracker#data Available at:

- 21.Szkultecka-Dębek M., Dzielska A., Drozd M., et al. What does the Cantril Ladder measure in adolescence? Arch Med Sci. 2018;14:182–189. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.60718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantril H. The pattern of human concern. Rutgers university press. 1965. https://ia801900.us.archive.org/27/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.139016/2015.139016.The-Pattern-Of-Human-Concerns.pdf Available at:

- 23.Chorpita B.F., Yim L., Moffitt C., et al. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: A revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:835–855. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravens-Sieberer U., Erhart M., Torsheim T., et al. An international scoring system for self-reported health complaints in adolescents. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:294–299. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin K.A., Currie C. Reliability and validity of an adapted version of the Cantril ladder for use with adolescent samples. Soc Indic Res. 2014;119:1047–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 26.CORC Revised children’s anxiety and depression scale (and subscales) (RCADS) https://www.corc.uk.net/outcome-experience-measures/revised-childrens-anxiety-and-depression-scale-and-subscales/ Available at:

- 27.Greene J.W., Walker L.S. Psychosomatic problems and stress in adolescence. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:1557–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erhart M., Ottova V., Gaspar T., et al. Measuring mental health and well-being of school-children in 15 European countries using the KIDSCREEN-10 Index. Int J Public Health. 2009;54:160–166. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pardo M.C., Alonso R. Working correlation structure selection in GEE analysis. Stat Pap. 2019;60:1447–1467. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moons K.G.M., Donders R.A.R.T., Stijnen T., Harrell F.E. Using the outcome for imputation of missing predictor values was preferred. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1092–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romaniuk H., Patton G., Carlin J. Multiple imputation in a longitudinal cohort study: A case study of sensitivity to imputation methods. AM J Epidemiol. 2014;180:920–932. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White I., Royston P., Wood A. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30:377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers A.A., Ha T., Ockey S. Adolescents’ perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: Results from a U.S.-based mixed-methods study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen Z.P., Cosgrove K.T., DeVille D.C., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health : Preliminary findings from a longitudinal sample of healthy and at-risk adolescents. Front Pediatry. 2021;9:622608. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.622608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zijlmans J., Teela L., van Ewijk H., Klip H. Mental and social health of children and adolescents with pre-existing mental or somatic problems during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:692853. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.692853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orgiles M., Morales A., Delveccio E., et al. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Preprint. 2020 doi: 10.31234/osf.io/5bpfz. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaditis A., Ohler A., Gileles A., et al. Effects of the COVID - 19 lockdown on sleep duration in children and adolescents : A survey across different continents. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56:2265–2273. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagenauer M.H., Perryman J.I., Lee T.M., Carskadon M.A. Adolescent changes in the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:276–284. doi: 10.1159/000216538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eaton D., McKnight-Eily L., Lowry R., et al. Prevalence of insufficient, borderline, and optimal hours of sleep among high school students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunster G.P., de la Iglesia L., Ben-Hamo M., et al. Sleepmore in Seattle: Later school start times are associated with more sleep and better performance in high school students. Sci Adv. 2018;4:0–7. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Au R., Carskadon M., Millman R., et al. School start times for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134:642–649. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thapar A., Collishaw S., Pine D.S., Thapar A.K. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379:1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose A., Rudolph K. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watkins D., Cheng C., Mpofu E., et al. Gender differences in self-construal: How generalizable are western findings? J Soc Psychol. 2003;143:501–519. doi: 10.1080/00224540309598459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO . WHO; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2020. Spotlight and Adolescent health and well-being. Findings from the 2017/2018 health-behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. International report, Volume 1. Key Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Widnall E., Winstone L., Mars B., et al. Young people’s mental health during the covid-19 pandemic: Initial findings from a secondary school survey study in SouthWest England. https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Young-Peoples-Mental- Health-during-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-Report-Final.pdf Available at:

- 47.Sun J., Stewart D. Age and gender effects on resilience in children and adolescents. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2007;9:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ioannidis K., Askelund A.D., Kievit R.A., Van Harmelen A.L. The complex neurobiology of resilient functioning after childhood maltreatment. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-1490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Health Behaviour in School-aged Children. About HBSC. http://www.hbsc.org/about/index.html Available at:

- 50.Viner R., Russell S., Saulle R., et al. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:400–409. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenthal N., Carpenter C., James S., et al. Seasonal affective disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:356–358. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.