Abstract

Nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma is a rare disease, with limited cases reported in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, there is no research detailing the treatment of nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma. In this present paper, we report an unusual case of a 70-year-old female patient with nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma. The patient was treated with radiotherapy alone. The detailed radiation therapy of the treatment was demonstrated. The patient is free of locally recurrent or distant disease at two years. Radiotherapy alone can be a helpful treatment for MALT lymphoma confined to the nasopharyngeal cavity.

Keywords: MALT lymphoma, Nasopharynx, Radiotherapy

Introduction

Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) lymphoma originated from the marginal zone of extranodal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. It mainly occurs in the gastrointestinal tract mucosa, as well as in other parts of the body such as the orbit, thyroid, and testis [1]. MALT lymphomas in the nasopharynx are extremely rare and generally misdiagnosed as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the adenoid due to a lack of specific symptoms and clinical signs [2]. The management of nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma remains unclear, and surgery or radiotherapy might be an alternative to other sites of MALT Lymphomas [3,4]. We have successfully treated one case of nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma, suggesting that radiotherapy alone might be an optimal treatment for the patient in stage IEA of the Ann-Arbor classification. Besides, the chart of the case was retrospectively collected, including clinical manifestations, imaging findings, pathological features, treatment details, radiotherapy information, and follow-up data. Hopefully, the treatment experience we shared could provide helpful evidence for others.

Case report

A 70-year-old female patient mainly presented with a 3-month history of left nasal congestion. The patient has not reported hearing loss in the left ear, diplopia, strabismus, vision loss, and cheek pain. Moreover, no fever had been observed from the initial occurrence of nasal obstruction. She initially went to see doctors in the otolaryngology department, and it was misdiagnosed as rhinitis. She accepted the associated treatment for rhinitis. However, there was no improvement in symptoms. Then, head-and-neck computerized tomography (CT) scan was performed for further evaluation. CT images exhibited a mess in the nasopharynx. The biopsy histologically verified that it was MALT lymphoma.

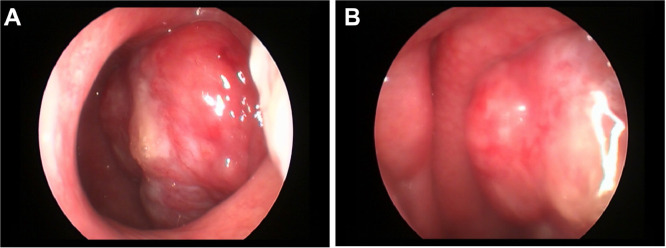

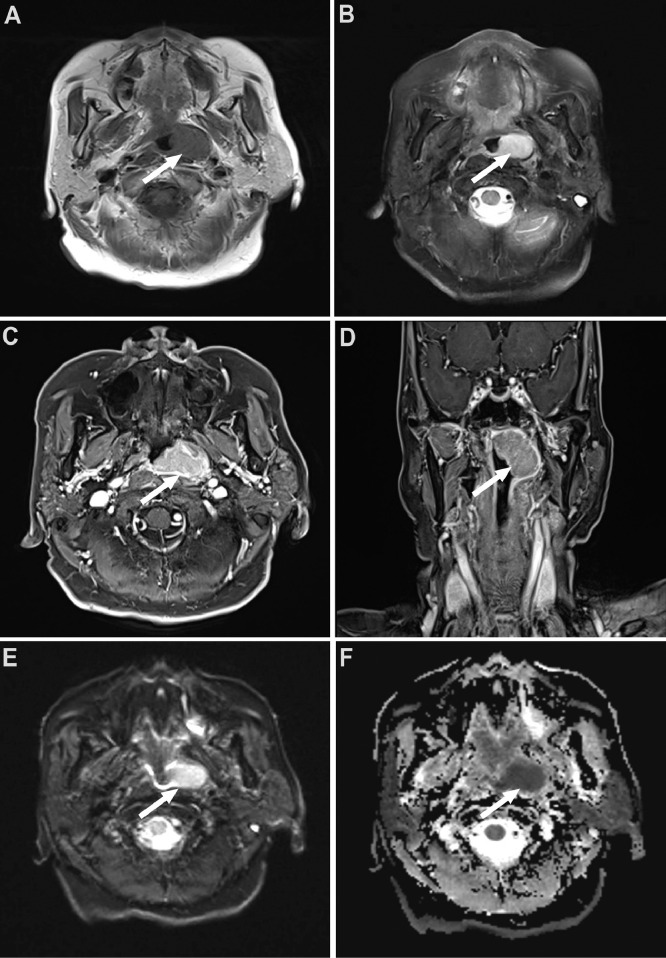

Karnofsky's performance status score of the patient was 100. Distant metastasis was excluded through the chest CT and abdominal CT. There was no bone marrow involvement. A neoplasm on top of the left nasopharynx was revealed by nasopharynxgolaryngoscopic examination. It is red and rough on the surface (Fig. 1). A CT scan of the paranasal sinuses presented a mass in the nasopharynx. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the nasopharynx displayed a diffuse mass in the left nasopharynx. The mass in T1-weighted images indicated iso-intensity while T2-weighted images suggested slight high-intensity, which was significant after enhancement (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Nasopharyngolaryngoscopic examination of NP MALT. It revealed a red mess with a harsh surface in the left pharyngeal recess.

Fig. 2.

MR images of NP MALT. (A) T1 axial; (B) T2 axial; (C)T1 axial enhanced; (D) T1 coronal enhanced; (D) and (E).

Routine laboratory tests demonstrated that lactate dehydrogenase level was 324U/l. Biopsy revealed chronic inflammation of the nasopharyngeal mucosa proliferation of lymphoid tissues infiltrated with the small cells, which were primarily marginal zone cells. It was diagnosed with MALT lymphoma, referring to immunohistochemistry. It stained as positive for CD20, CD21, CD3(part+), CD30(+), CD43(part+), CD79a (partial), and BCL-2(partial), and negative for CD5, CD10, CD23, CD56, Bcl-6(-), CyclinD1(-), and EBER. The Ki67 index score was 30%. Jaso and Chen's study of 15 patients’ review with MALT lymphoma found that MALT lymphoma is a B-cell neoplasm that is typically CD5 negative [5].

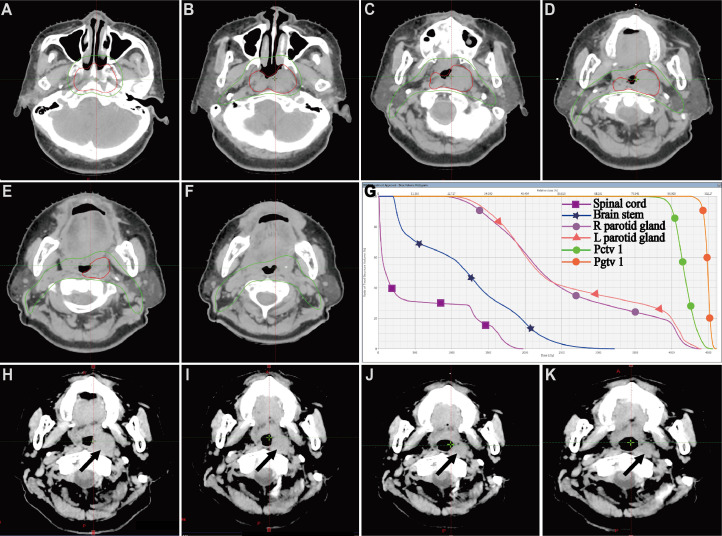

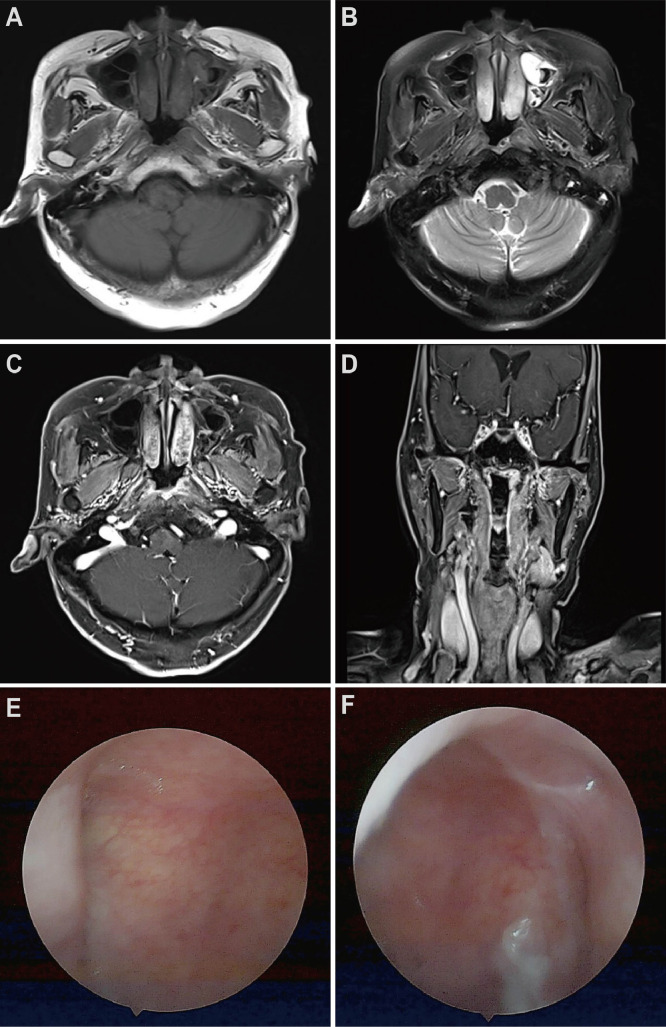

According to the clinical examination and image findings, the lesion was staged into IEA following the Ann-Arbor staging system. The patient was planned to receive radiation therapy. A head-and-neck mask was made under the CT simulation. The scanning range was from the top of the skull to the subclavian, and the slice thickness of scanning is 2.5 mm in every slice of the head and neck. Two experienced doctors cooperated to delineate the target on the patient's CT-MRI fusion images. By imaging and physical examination, the gross tumor volume (GTVp) was defined as the gross extent of the tumor. According to the primary tumor, the clinical target volume (CTV) covered the parts of the whole nasopharyngeal cavity. Preparation for intensive modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) plans to design; GTVp was executed with a schedule of 2.0 Gy per fraction, 20 fractions, a totally 40 Gy; CTV was delivered with a schedule of 1.8 Gy per fraction, a total of 20 fractions. After the dosimeter and physicist verified the plan, the patient received the radiotherapy. The patient plan was designed through the Varian treatment planning system. The treatment target dose met 95% of the volume to reach the prescribed dose. The maximum dose to the brainstem (3 mm outer) was 39.4 Gy. The average dose of parotid glands on both sides was lower than 20 Gy. After 10 Gy of external beam irradiation, an examination and CT scan of the nasopharynx were performed on the patient. It suggested that the mass in the nasopharynx partially shrunk. During 20 Gy and 30 Gy of external beam irradiation, the patient was also examined by a CT scan and physical examination. The patient had no discomfort with the treatment and presented significantly decreased nasopharyngeal mass. The evaluation still suggested a small residual lesion in the nasopharynx. Thus, we decided to add the total dose to 40 Gy. After 40 Gy of routine external beam irradiation, the patient was examined by a CT scan. The patient's pharynx was significantly hyperemia. CT images exhibited that the tumor was retreating significantly (Fig. 3). The tumor in the left nasopharyngeal wall disappeared in both MR images and the nasopharyngolaryngoscopic examination 6 months after the completion of treatment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

CT images of NP MALT. (A), (B), (C), (D), (E), (F) showed the typical images of contouring of gross tumor volume and targeted clinical volume. (G) presented the dose-volume histogram of the tumor and several vital organs at risk. (H), (I), (J), (K), presented the tumor accepting 10 Gy, 15 Gy, 20 Gy, and 25 Gy radiation.

Fig. 4.

(A) T1 axial; (B) T2 axial; (C) T1 axial enhanced; (D) T1 coronal enhanced on MR images of NP MALT after the 12 months of radiotherapy. (D) and (E) are the nasopharyngolaryngoscopic examinations.

Discussion

MALT lymphoma, a disease with distinct pathogenesis triggered by chronic inflammatory processes [6], is a unique type of low-grade B-cell lymphoma, generally with no specific clinical symptoms, arising from lymphoid populations that are induced by chronic inflammation in extranodal sites [7]. According to Huseh and Chien's literature, MALT lymphoma accounts for 8.6% of the total incidence of nasopharyngeal lymphoma [3]. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue accounts for 7%-8% of newly diagnosed lymphomas [8]. It can occur in any extranodal location but mainly in the stomach, skin, lungs, eyes, and salivary glands [9,10]. Many patients were delayed in diagnosis for several years because MALT lymphoma is defined as an indolent tumor and progresses slowly [11,12]. Since the incidence of MALT lymphoma in the nasopharynx is extremely low, few treatment options are available for clinical practice [13,14]. Therefore, we hope to present a case of nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma, which was successfully treated in our institution.

PET/CT is a noninvasive and practical examination for MALT lymphomas. However, some investigators suspected its effect on staging and evaluation for MALT lymphoma and its prediction ability for the treatment response [15,16]. Accordingly, the patient was not suggested to perform PET/CT scan in this case at an early stage. In MALT lymphoma, the bone marrow invasion was less than two percent in such an early stage lesion, and bone marrow biopsy was not executed [17,18]. The chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT scans were conducted to exclude distant metastatic lesions.

The treatment of MALT lymphoma includes surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, antibiotics, immune drugs, and combined therapy [19,20]. Based on the results published to date, immunomodulatory treatment is a logical and promising treatment strategy for extranodal lymphoma of MALT type, but more prospective data are needed to clearly position these agents in the treatment algorithm [21], [22], [23], [24]. The literature from CA Cancer J Clin showed that therapeutic management of MALT lymphomas is extremely heterogeneous, and universally accepted therapeutic guidelines do not exist [8].

According to Tsang Richard's article, because there is a tendency for the disease to remain localized for a long time, local treatment, such as radiotherapy (RT), has been widely used as an optimal choice for early-stage lesions over the past few decades [25]. Moreover, radiotherapy doses vary according to the different lesion sites, generally 25-36 Gy and 30-35 Gy for ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma and MALT lymphoma of other organs, respectively [26], [27], [28]. MALT lymphomas are sensitive to external beam radiotherapy. Local control is very successful [1,29]. Surgery is strongly associated with the range of focal lesions. Due to the high local recurrence, surgery is not the first choice for nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma. According to reports in the literature, related cases were treated with combined chemotherapy (CHOP regimen) and combined radiotherapy after resection. Other researchers revealed that chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy was a preferred treatment option for nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma [3,30]. Although chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy has a more significant survival benefit for patients in the advanced stage, chemotherapy alone is not sufficient to control the disease in the early stage compared with radiotherapy.

Owing to the early stage disease and patient's age, definitive radiotherapy was delivered in this case. Radiation dose is a concerning problem. Tsang et al. reported that the median RT dose was 30 Gy (range, 17.5-35 Gy), and the most frequent doses were 25 Gy, 30 Gy, and 35 Gy for IEA and ⅡEA MALT [25,31]. We planned the dose of 36-40 Gy and monitored the tumor response during radiotherapy every week. If the tumor was susceptible to radiation, the dose was deescalated to less than 36 Gy, and the dose was decided to 40 Gy according to the tumor decrease.

Since there is no basis for reference, we innovatively attempted to conduct intensive CT evaluations of patients. CT evaluations were performed on the patient weekly. The tumor shrinkage was observed according to the gradual increase in the radiation dose. The comparison of CT images revealed that the tumor had retreated well. After the radiotherapy, the tumor had shrunk completely.

Conclusion

Nasopharyngeal MALT lymphoma is frequently misdiagnosed as nasopharyngeal carcinoma. It is a rare head and neck tumor and needs to be diagnosed with multiple factors through pathology. Radiotherapy alone can be a helpful treatment for MALT lymphoma confined to the nasopharyngeal cavity.

Patient consent

Informed consent for patient information to be published in this article was obtained.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment: No funding supports the publication of this case report.

References

- 1.El-Banhawy O A, El-Desoky I. Low-grade primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the nasopharynx: clinicopathological study. Am J Rhinol. 2005;19(4):411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Hawary A K. Histopathological assessment and immunohistochemical study of nasopharyngeal low grade MALT lymphoma. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2006;18(2):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsueh C, Yang C, Gau J, Kuan E C, Ho C, Chiou T, et al. Nasopharyngeal lymphoma: a 22-year review of 35 cases. J Clin Med. 2019;8(10):1604. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundaram K, Singh B, Har-El G. Nasopharyngeal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20(1):56–58. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(99)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaso J, Chen L, Li S, Lin P, Chen W, Miranda R N, et al. CD5-positive mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Human Pathol. 2012;43(9):1436–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiesewetter B, Raderer M. How can we assess and measure prognosis for MALT lymphoma? A review of current findings and strategies. Expert Rev Hematol. 2021;14(4):391–399. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2021.1909468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thieblemont C, Zucca E. Clinical aspects and therapy of gastrointestinal MALT lymphoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2017;30(1):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raderer M, Kiesewetter B, Ferreri AJ. Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):153–171. doi: 10.3322/caac.21330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soweid A M, Zachary PJ. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the oesophagus. Lancet. 1996;348(9022):268. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)65577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayerdorffer E, Neubauer A, Rudolph B, Thiede C, Lehn N, Eidt S, et al. Regression of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Lancet. 1995;345(8965):1591–1594. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Zhou F. Successful conservative treatment of primary endometrial marginal zone lymphoma (MALT type): a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:16.e15331. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zapparoli M, Trolese A R, Remo A, Sina S, Bonetti A, Micheletto C. Subglotic malt-lymphoma of the larynx: an unusual presentation of chronic cough. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27(3):461–465. doi: 10.1177/039463201402700319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson S D, Musleh W, Gurbuxani S, Shafizadeh S F, Lesniak MS. Intracranial mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17(5):666–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zinzani P L, Magagnoli M, Galieni P, Martelli M, Poletti V, Zaja F, et al. Nongastrointestinal low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: analysis of 75 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albano D, Durmo R, Treglia G, Giubbini R, Bertagna F. (18)F-FDG PET/CT or PET role in MALT lymphoma: an open issue not yet solved-a critical review. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(3):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albano D, Bosio G, Camoni L, Farina M, Re A, Tucci A, et al. Prognostic role of baseline (18) F-FDG PET/CT parameters in MALT lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(1):39–46. doi: 10.1002/hon.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J Y, Kim S G, Kim J S, Jung HC. Bone marrow involvement is rare in superficial gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48(1):81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi S I, Kook M C, Hwang S, Kim Y I, Lee J Y, Kim C G, et al. Prevalence and implications of bone marrow involvement in patients with gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Gut Liver. 2018;12(3):278–287. doi: 10.5009/gnl17217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Defrancesco I, Arcaini L. Overview on the management of non-gastric MALT lymphomas. Best practice & research. Clin Haematol. 2018;31(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao Z, Ha C S, McLaughlin P, Manning J T, Hess M, Cabanillas F, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with initial supradiaphragmatic presentation: natural history and patterns of disease progression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(2):399–403. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00628-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiesewetter B, Raderer M. Immunomodulatory treatment for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT lymphoma) Hematol Oncol. 2020;38(4):417–424. doi: 10.1002/hon.2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jhavar S, Agarwal J P, Naresh K N, Shrivastava S K, Borges A M, Dinshaw KA. Primary extranodal mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the prostate. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2001;41(3-4):445–449. doi: 10.3109/10428190109058003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahlawat S, Kanber Y, Charabaty-Pishvaian A, Ozdemirli M, Cohen P, Benjamin S, et al. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma occurring in the rectum: a case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 2006;99(12):1378–1384. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000215855.98512.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Angelis F, Annechini G, Agostinelli C, D Elia G M, Panfilio S, Pulsoni A. Primary uterine localization of malt lymphoma: a case report and literature review. Leukemia research. 2011;35(11):e185–e187. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsang R W, Gospodarowicz M K, Pintilie M, Bezjak A, Wells W, Hodgson D C, et al. Stage I and II malt lymphoma: results of treatment with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys. 2001;50(5):1258–1264. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01549-8. doi:https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lalya I, Mansouri H. Images in clinical medicine. Bilateral lower palpebral MALT lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):363. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1400091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ioakeim-Ioannidou M, MacDonald SM. Evolution of care of orbital tumors with radiation therapy. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2020;81(4):480–496. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haque S, Noble J, Wotherspoon A, Woodhouse C, Cunningham D. MALT Lymphoma of the Foreskin. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2004;45(8):1699–1701. doi: 10.1080/10428190410001683813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thieblemont C, Berger F, Dumontet C, Moullet I, Bouafia F, Felman P, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma is a disseminated disease in one third of 158 patients analyzed. Blood. 2000;95(3):802–806. doi: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Violeta Filip P, Cuciureanu D, Sorina Diaconu L, Maria Vladareanu A, Silvia Pop C, Davila C. University Of Medicine and Pharmacy B, et al. MALT lymphoma: epidemiology, clinical diagnosis and treatment. J Med Life. 2018;11(3):187–193. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayakawa T, Nonaka T, Mizoguchi N, Hagiwara Y, Shibata S, Sakai R, et al. Radiotherapy for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the rectum: a case report. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10(5):431–436. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]