Abstract

The deceptively simple concepts of mass determination and fragment analysis are the basis for the application of mass spectrometry (MS) to a boundless range of analytes, including fundamental components and polymeric forms of nucleic acids (NAs). This platform affords the intrinsic ability to observe first-hand the effects of NA-active drugs on the chemical structure, composition, and conformation of their targets, which might affect their ability to interact with cognate NAs, proteins, and other biomolecules present in a natural environment. The possibility of interfacing with high-performance separation techniques represents a multiplying factor that extends these capabilities to cover complex sample mixtures obtained from organisms that were exposed to NA-active drugs. This report provides a brief overview of these capabilities in the context of the analysis of the products of NA-drug activity and NA therapeutics. The selected examples offer proof-of-principle of the applicability of this platform to all phases of the journey undertaken by any successful NA drug from laboratory to bedside, and provide the rationale for its rapid expansion outside traditional laboratory settings in support to ever growing manufacturing operations.

Keywords: Drug discovery, drug development, ADME, native MS, ligand binding, nucleic acids analysis

The essential functions performed by nucleic acids (NA) in living organisms provide the rationale for their vast potential as both drug targets and therapeutic agents. Since the first data on the possible therapeutic properties of nitrogen mustards were declassified after World War II [1,2], the biomedical community has been engaged in the endless pursuit of ever more effective small-molecule drugs capable of inhibiting such functions by either inducing chemical modification [3,4] or establishing specific binding interactions with desired NA targets [5–7]. In the late Seventies, the observation that synthetic oligonucleotides (ON) were capable of affecting gene expression in cells [8,9] opened the door for the utilization of these biopolymers as drugs in their own right, capitalizing on the specificity of target recognition afforded by the base complementarity rules [10,11]. More recently, the remarkable success of mRNA-based vaccines in controlling the pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has introduced the general public to the virtues of these biomolecules as vehicles for establishing the expression of key proteins capable of inducing an immune response, or mitigating possible deficiencies of endogenous production [12,13]. The growing significance of these types of therapeutics to public health has greatly increased the emphasis on the analytical tools necessary to cover the long and perilous journey from discovery to actual patient administration. Mass spectrometry (MS) has been rapidly advancing to the forefront of the techniques of choice for NA analysis, mirroring the trajectory of its application to other classes of pharmaceuticals. At the basis of this sustained expansion are the proverbial sensitivity, selectivity, and speed afforded by this analytical platform, to which one should add versatility. This review covers the multifaceted applications of this technique to all aspects of discovery and development of NA-related therapeutics, and offers a critical commentary on benefits and limitations, as well as possible glimpses of what the future might hold. Historic references were included to provide the perspective necessary to appreciate the progress made by the field since its origins. In some cases, the introduction of more effective approaches associated with the relentless evolution of MS instrumentation has resulted in a dearth of newer references for some concepts/techniques. In others, the absence of more recent references constitutes a testament to the broad adoption of such concepts/techniques, which have become common practice in NA research. This review is also meant to provide neophytes with an entry point and possible roadmap to explore an unfamiliar field. For this reason, references to original publications are complemented by those to fundamental reviews, books, and other material, which we hope will encourage and facilitate further readings.

A. Molecular mass determination of chemically modified NAs

Accurate mass determinations can provide valuable information on the identity of NA analytes, their integrity, and the possible presence of chemical modifications. Over the years, this type of analysis has supported the characterization of reaction products generated by the attack of potential drugs onto NA targets, the assessment of reactivity and specificity of such attack, and the elucidation of possible mechanisms of action. These types of studies are typically accomplished by examining fundamental NA components, such as nucleobases, nucleosides, and nucleotides, or larger analytes consisting of ribo- and deoxyribo-ONs of different sizes [14–16]. Determinations are preferentially carried out in negative ion mode to capitalize on the deprotonation of the highly acidic phosphate groups, although positive ions can be also detected by virtue of possible “wrong-way-round” ionization effects [17]. Electrospray ionization (ESI) [18,19] and matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) [20,21] have established themselves as the preferred techniques for these analytes. Before their broad diffusion, however, fast atom bombardment (FAB) [22] and other legacy ionization techniques established solid foundations for the characterization and quantification of xenobiotic modifications of mono-nucleosides/nucleotides and relatively small ON products. In this direction, reference [23] provides a retrospective view of what represented the state of the art before ESI and MALDI became predominant.

Traditional approaches for adduct analysis rely on the hydrolysis of the initial samples, which may range from model ONs to DNA extracts treated in vitro with the compound of interest, to actual biological material obtained from animal models or patients who were exposed to the xenobiotic. The typically low incidence of adduct formation in living organisms implies that the modified components must be detected in the presence of an overwhelming background containing their corresponding unmodified versions, as well as complex biological matrices. The complexity of these samples and the sensitivity demands have promoted approaches combining enrichment procedures with high-resolution separation techniques, such as gas chromatography (GC)[24], liquid chromatography (LC)[25], and capillary electrophoresis (CE)[26], which have become the workhorses of the rapidly expanding field of DNA adductomics [27,28]. The GC-MS analysis of DNA modifications produced by genotoxic compounds can be successfully accomplished by using electron capture (EC) ionization as the interface of choice [29,30]. It has been shown that this approach is capable of achieving sensitivity levels of approximately 1 adduct per 108 nucleotides with practical sample consumption ranging from 1 to 100 μg of DNA [30]. Comparable capabilities have been demonstrated also by LC-MS approaches that utilize the ESI interface and capitalize on the excellent specificity afforded by linked scans in MS/MS mode (comprehensively reviewed in ref. [31]). The fact that these approaches are readily applicable to the analysis of modified nucleosides excreted in urine [32–34] suggests that they could play a prominent role in the investigation of the metabolism of alkylating drugs, as well as that of NA therapeutics that incorporate unconventional building blocks to facilitate delivery or enhance their pharmacokinetics profiles (vide infra).

Molecular mass determination of intact oligonucleotides has traditionally benefited the drug discovery/development by enabling the elucidation of adducts produced by alkylating or metal-based therapeutics with anticancer activity. For example, the process of tamoxifen (Scheme 1) activation in mammalian hepatocytes was investigated by using 32P-postlabelling and LC-MS to monitor its oxidation to α-hydroxytamoxifen and the formation of DNA adducts [35]. The putative mechanism of action of fotemustine (Scheme 1), a new member of the 2-chloroethyl-1-nitrosourea family, was probed by flow injection ESI-MS, which revealed the formation of at least two intermediates responsible for the cytotoxic activity of this potential anticancer agent [36]. The same approach was employed to demonstrate the ability of the antitumor antibiotic hedamycin (Scheme 1) to form covalent adducts with relatively short DNA duplexes (Figure 1) [37] and to investigate the reactivity of the topoisomerase II inhibitor clerocidin (Scheme 1) [38,39]. These studies revealed that clerocidin was capable of reacting not only with intended DNA substrates, but also with off-target nucleophilic species (i.e. buffer components) present in the environment, which were shown to adversely affect drug activity [40]. In similar fashion, MALDI was utilized to characterize the products and reaction intermediates generated by treating single- and double-stranded DNA models with the antitumor drug cisplatin (Scheme 1) [41], and those obtained by reacting different polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)-diol-epoxides with calf thymus DNA [42]. On one hand, this type of information has been traditionally used to elucidate the putative mechanism of action, to identify reactivity determinants, and to drive the refinement of initial lead compounds. On the other, it has also helped trace the possible metabolic fate of the corresponding NA conjugates, thus providing essential knowledge necessary to fulfill regulatory requirements.

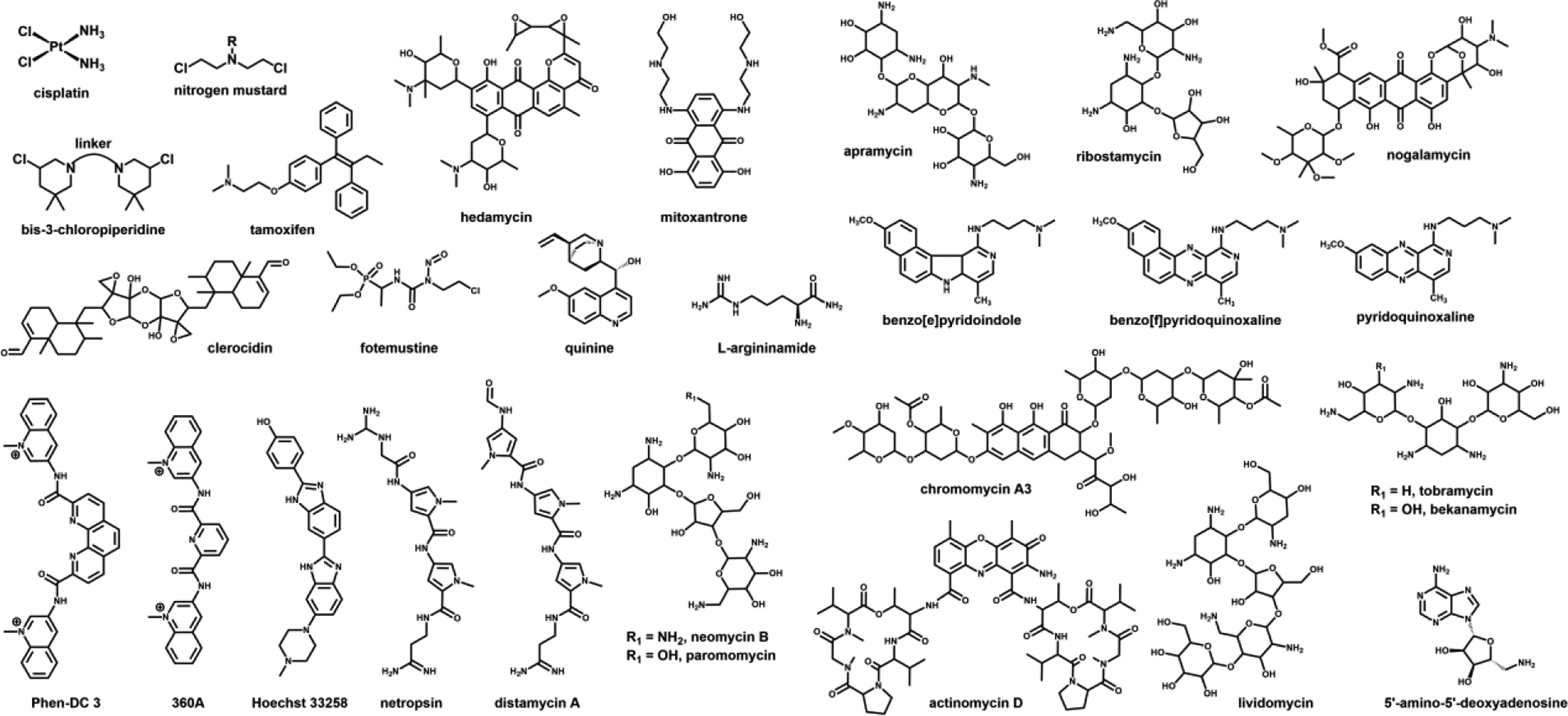

Scheme 1.

Structures of NA-active drugs/ligands utilized in the examples discussed in the text.

Figure 1.

ESI-MS spectra obtained from a mixture of hedamycin (Scheme 1) and d(CACGTG) (a) following HPLC purification and (b) after further addition of d(CACGTG). The former displays only a single-stranded hedamycin-d(CACGTG) adduct, whereas the latter reveals the formation of hedamycin-d(CACGTG)2 with a duplex structure. Reproduced with permission from ref. 37.

B. Sequence determination of drug-NA adducts and ON therapeutics

A very valuable quality of the MS platform is the ability to support a variety of approaches for determining the sequence of NA analytes, which is required to complete the full characterization of drug-NA adducts and ON therapeutics. Two distinct categories can be readily distinguished, which involve either the mass analysis of sequence-specific products generated in solution by ad hoc chemical or enzymatic reactions (a helpful primer is provided by ref. [43]), or tandem MS determinations relying on the direct gas-phase cleavage of the phosphodiester linkages of the biopolymer’s backbone (covered in excellent detail in ref.s [16,44]). These types of approaches have found extensive use not only in the identification of the sequence position of modifications introduced by genotoxic agents and NA-active drugs, but also in the characterization of natural modifications introduced by specialized enzymes present in the cell [45]. In this direction, it should be noted that the investigation of RNA post-transcriptional modifications (rPTMs) has historically represented a powerful driving force in the development of both analytical [46–48] and software [49–55] tools for MS-based NA analysis. Indeed, the possibility of applying such tools to both RNA and DNA samples, as well as to natural and xenobiotic-induced modifications, was realized early on [23] and provided motivation for the extensive cross-pollination that has remained a constant in the field.

Solution-phase approaches involve generating series of ON products (i.e., ladders) by controlled hydrolysis of the target strand, or halted enzymatic synthesis of complementary copies [43]. Subsequent mass analysis can then reveal the identity and sequence position of each nucleotide from the difference in mass between consecutive members of the ladder. The presence of modified nucleotides, however, can significantly affect the preparation of informative ladders and subsequent data interpretation. For example, the formation of hydrolytic ladders relies on the activity of specific 5’- and 3’-exonucleases that proceed stepwise from one end of the strand to the other. The ability of bulky modifiers to halt the progress of these exonucleases may result in incomplete ladders that effectively preclude the possibility of acquiring information on the downstream sequence. This effect might not necessarily lead to a negative outcome, if the goal of the experiment is to identify the location of the modification within a known sequence [56,57]. In chain-termination approaches, the activity of DNA polymerase is purposely halted by the incorporation of appropriate dideoxynucleotides present in the reaction mixture, which results in the formation of stunted complementary products [58–61]. The partial copies do not bear any trace of the actual modification present in the genuine template and, thus, do not afford per se any useful information. However, the position of a non-canonical nucleotide can be still inferred in indirect fashion if the modifier is capable of altering the base-pairing rules or causing elongation inhibition. The first scenario will lead to the mispairing of an incorrect dideoxynucleotide, which will be revealed by comparing the observed sequence with that obtained in parallel from an unmodified template strand. The second scenario will result in the unintended incorporation of a regular deoxynucleotide at the end of the terminated product, in place of the dideoxynucleotide expected from a normal termination event.

Gas-phase approaches involve the activation of a selected precursor ion in a tandem MS experiment, which results in the systematic cleavage of the biopolymer’s phosphodiester bonds with formation of characteristic fragment series (Scheme 2) [62,63]. Typical collision-induced dissociation (CID) conditions lead to preponderant formation of a-B and w fragments from deoxyribo-ON precursors, and c and y fragments from ribo-ONs. In analogy with solution phase strategies, the sequence position of each biopolymer unit is inferred from the difference in mass between consecutive signals in a given series. Therefore, modified nucleotides can be readily identified from distinctive mass shifts over the corresponding unmodified versions. In some cases, however, the nature of the modification may unduly favor a certain fragmentation pathway over the others, which may hinder the acquisition of sufficient information to cover the entire sequence. This is the case of nucleobase losses that tend to become the most prominent processes observed upon base modification [64–66]. In particular, the covalent attack to the N7 nucleophilic position of purines is known to weaken the corresponding N-glycosidic bond, which promotes depurination and strand cleavage at the ensuing abasic site. This effect has been observed for a wide range of electrophilic agents including metal-based therapeutics [67–71] and alkylating drugs, such as oxirans [37,72], nitrogen mustards [73,74], bis-3-chloropiperidines [75–77], and many others (Scheme 1). This observation has spurred the systematic exploration of alternative activation techniques to identify possible solutions for minimizing base losses in favor of backbone fragmentation (reviewed in depth in ref. [78]). These studies demonstrated that submitting DNA/cisplatin adducts to infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) or ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) provided the most extensive possible sequence coverage, which afforded the best chances of pinpointing the adduct position [79,80].

Scheme 2.

Characteristic fragment series generated by gas-phase activation of NA precursor ions. Typical a-B fragments are generated by the concomitant loss of nucleobase and cleavage of the 3’ C-O bond. B corresponds to any nucleobase. R corresponds to H in deoxyribo-ONs; OH in ribo-ONs; and CH3O in 2’O-methyl-ribo-ONs. X corresponds to OH in deoxyribo- and ribo-ONs; SH in phosphorothioate-ONs; and CH3 in methylphosphonate-ONs.

The gas-phase behaviors of products generated by metal-based and bi-functional alkylating drugs can be profoundly affected by the possible formation of intra- and inter-molecular cross-links. For example, base loss remained the dominant process exhibited by 1,2-cisplatin adducts bridging adjacent Gs on the same strand, which still allowed the detection of sufficient w ions to identify the platination sites [66]. However, the detection of these diagnostic fragments was considerably reduced in the case of inter-strand cross-links in duplex constructs, or more complex higher-order structures [81]. As shown in Figure 2, the tandem mass spectra obtained by collisional activation of cisplatin adducts with homo- and hetero-bimolecular G-quadruplexes are dominated by the products of strand dissociation, rather than sequence-specific fragments. The study identified the nature of the bridged nucleotides and their structural context as the factors determining the observed outcomes. Indeed, the fact that the homo-bimolecular structure placed two A nucleotides in contiguous loop regions promoted the formation of a cross-linked conjugate that dissociated in symmetrical fashion to produce platinated and un-platinated strands with equal abundances (Figure 2a). In contrast, the hetero-bimolecular structure promoted the bridging of G and A sites on cognate strands, which dissociated in asymmetrical fashion by virtue of the greater affinity of Pt for the N7 of the former than that of the latter (Figure 2b). Along these lines, the gas-phase behavior of species obtained by treating NA substrates with bis-3-choloropiperidine analogues provided valuable information on the putative mechanism of action of this novel class of topoisomerase II inhibitors [75–77]. In concert with denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and MS-based solution melting experiments, tandem MS confirmed the formation of incomplete (a.k.a. “dangling”) mono-functional adducts and enabled the unambiguous discrimination of intra- versus inter-molecular conjugates that shared the same elemental composition and therefore mass [82]. The results helped explain the different outcomes observed with DNA and RNA substrates, which consisted predominantly of strand cleavage versus inter-strand conjugation, respectively. This mechanistic information provided the insights necessary to formulate possible solutions for enhancing the target specificity of these novel therapeutics. Similar concerted approaches have demonstrated their value in the investigation of the cross-linking properties of a variety of alkylating agents not only with NA-NA substrates but also with protein-NA targets of potential biomedical interest [83].

Figure 2.

Product ion spectra obtained from the (a) [QB2 + 3NH4+ + cisPt2+−11H+]6- and (b) [QB23 + 3NH4+ + cisPt2+−11H+]6- precursor ions at m/z 1406.923 and 1409.872, respectively. These species were generated by treating homo-bimolecular d(GGGGTCATTGGGG)]2 (QB2) and hetero-bimolecular d(GGGGTCATTGGGG)]·[d(GGGGTCGTTGGGG)] (QB23) quadruplexes with cisplatin (insets). Reproduced with permission from ref. 81.

An area that has recently experienced great expansion is the application of tandem MS to the sequence determination of synthetic ON analogues utilized to create putative NA therapeutics, which tend to elude the leading next generation sequencing (NGS) techniques [84–86]. Indeed, different types of analogues have been developed over the years to facilitate their delivery, extend the half-life in the patient’s organism, increase the affinity and selectivity of binding interactions, and minimize possible off-target effects (Scheme 3) [87–89]. Among them, the more prominent are characterized by the presence of methoxy or fluorine substituents at the 2’ position of the pentose moiety [90]; the substitution of backbone phosphates with methylphosphonate, phosphorothioate, or phosphoroamidate groups [91]; the introduction of an additional 2’-C, 4’-C-oxymethylene link to create locked nucleic acids (LNAs) [92]; and the complete replacement of the familiar phospho-pentose backbone with repeating units of N-(2-aminoethyl)-glycine linked by carbamidic bonds (peptide nucleic acids, PNAs) [93]. Each of these variations can have distinctive effects on the respective fragmentation patterns that may differ significantly from those of the canonical biopolymers [44]. For example, masking the 2’ position with fluorine or methoxy groups stabilizes the adjacent N-glycosidic bond, but also eliminates the exchangeable 2’-proton that drives the fragmentation of unmodified ribo-ONs [94–96]. Therefore, the observation of the same c and y series (Scheme 2) that are normally exhibited by this type of biopolymer implied significant alterations of the underlying cleavage mechanism [69]. Substituting regular phosphates with methylphosphonates induced more significant variations that were ascribed to the shift of typical charged sites from backbone to nucleobase locations. As a consequence, fully modified deoxyribo-ONs exhibited the lack of expected a-B fragments in favor of a/w and d/z ion series [97]. Phosphorothioate analogues behaved more closely to canonical deoxy-ONs, while displaying an increased incidence of b/x and c/y fragments, thus suggesting that the cleavage of this type of linkage possessed a somewhat lower activation barrier [98]. Further studies revealed that the P–O bond at the 5’ side of the sulfur enjoyed greater stability than normal under CID and IRMPD activation, which offered the opportunity to selectively locate phosphorothioate sites by using UVPD and a series of hybrid activation techniques [99,100]. The restrained conformation of LNAs, which is determinant to their greater binding affinity towards complementary sequences, did not appear to favor any particular fragmentation pathway [101]. Mixed DNA/LNA sequences, however, revealed that the phosphate bonds with the locked units were somewhat more stable than those with regular deoxynucleotide counterparts, which resulted in the preferential cleavage of the 3’- C–O bond of the latter. Collisional activation of PNA samples displayed behaviors resembling those of both peptide and ON species, including the cleavage of the carbamidic bond and loss of water characteristic of the former, and the loss of nucleobase typical of the latter [102,103].

Scheme 3.

Structures of common NA analogues employed to create NA therapeutics. LNA indicates locked nucleic acids. Panel B) shows the structure of typical peptide nucleic acids (PNAs).

Regardless the selected activation mode, tandem MS can typically afford full-sequence coverage for strands of up to ~25 nucleotides in routine analysis. Although direct gas-phase sequencing (defined as top-down) has been shown capable of providing extensive information on unmodified [104–106] and modified [107–109] strands reaching up to ~100 nucleotides, the possibility of achieving adequate coverage for progressively larger analytes is limited by the ability of such ions to dissipate the imparted energy through an increasing number of vibrational modes. For this reason, a series of bottom-up strategies have been developed, which involve partial digestion of the initial analyte into smaller hydrolytic products that can be comfortably mapped and sequenced by hyphenated MS techniques (vide infra) [16]. Over the years, the broad adoption of top-down and bottom-up strategies has been promoted by the introduction of a variety of software aids for the interpretation of data obtained from either DNA [110–112] or RNA samples [49–55].

C. High performance separations for the characterization of complex NA samples

The implementation of front-end separations can significantly increase the reach of MS-based approaches for NA analysis, along the same lines traced by the analysis of peptides and proteins. With ad hoc adjustments dictated by the different physicochemical properties of these biopolymers, similar hyphenated techniques are regularly employed to support the characterization of samples representing possible targets of NA-active drugs, products of drug activity, actual NA therapeutics, and more. Indeed, LC-MS and LC-MS/MS approaches have now become essential to the assessment of both the identity and purity of anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and similar ON products of less than ~100 nt, which can be readily obtained by solid-phase synthesis. Their broad application to larger RNA products (i.e., greater than ~100 nt) obtained by in vitro transcription, such as putative mRNA therapeutics, is just around the corner. In addition to putative synthesis biproducts, the utilization of an ever‐increasing number of modified nucleotides to increase product stability and bioavailability is another source of heterogeneity that contributes to the complexity of typical product mixtures [113]. The challenges posed by these types of samples represent a powerful driving force behind the introduction of a variety of approaches based on LC-MS and LC-MS/MS analysis (recently reviewed in ref. [114]).

The majority of the established chromatographic approaches for ON analytes, such as size-exclusion [115,116], anion-exchange [117,118], mixed-mode [119], and affinity chromatography [120], involve mobile phases containing elevated concentrations of non-volatile salts and additives, which require the implementation of extensive desalting procedures immediately prior to any offline MS analysis. Over the years, however, the introduction of volatile solvent systems has enabled the direct online interfacing of the MS platform with ion-pair reversed-phase (IP-RP) chromatography [121–125]. This type of separation employs alkyl-amine/ammonium derivatives and similar amphiphilic compounds as ion-pairing agents capable of masking the negative charges on the backbone phosphates and increasing the overall hydrophobic character of the analytes [126]. The interactions between ion-paired species and hydrophobic stationary phase (typically C18) are modulated by changing the organic character of the mobile phase. Common MS-compatible systems include different concentrations of tri-ethylammonium (TEA) and hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), which have been shown to improve both chromatographic separation and detection sensitivity [127]. Additionally, separations based on hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) [128] have gradually emerged as valid alternatives to IP-RP chromatography by virtue of relatively volatile mobile phases that greatly facilitate direct interfacing with MS analysis [129,130]. In this type of system, the polar stationary phase is covered by a water layer that enables the partitioning of polar analytes with a highly organic mobile phase (i.e., typically based on acetonitrile or 2-propanol). HILIC has been recently combined with either IP-RP or anion exchange chromatography (AEX) to perform the identification of oligonucleotide impurities as low as 0.3% [131]. Excellent primers for learning more about these types of applications are provided in ref. [132] and [133].

The rapid emergence of therapeutic strategies based on mRNA [13], which has been further accelerated by the success of mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 [134,135], has keenly exposed the need for analytical approaches capable of handling progressively larger NA samples. The potential of LC-MS for the characterization of these types of therapeutics can be exemplified by a report describing the investigation of the factors that affected the enhancing activity of the 3’-poly(A) tail on mRNA stability and translation [136]. Poly(A) tails of different lengths were encoded in a series of template plasmids to mimic the possible sizes observed in natural mRNAs. Upon in vitro transcription, the poly(A) sections were released from the recombinant products by treatment with RNase T1, which specifically cleaves G nucleotides, and then isolated by using magnetic beads coated with poly-dT ONs. The LC-MS analysis of the affinity-captured products displayed a much broader size distribution than expected from the templates, which provided proof of the extensive slippage experienced by T7 RNA polymerase during poly(A) transcription. In another mRNA application, LC-MS was employed to verify the base composition of products obtained by in vitro transcription in the presence of selected adenosine triphosphate (ATP) analogs [137]. The approach involved exhaustive exonuclease digestion of the initial strands into their respective mono-nucleotide components. The study aimed at assessing the ability of different RNA polymerases to incorporate α-phosphate analogs that contained either O-to-S or O-to-BH3 substitutions, and demonstrated that their presence in the poly(A) tail led to significant protection against 3’adenylase degradation. Approaches combining exonuclease digestion with LC-MS analysis have long represented an important staple in the characterization and quantification of natural RNA modifications, which has been the object of dedicated reviews [138–140].

The fact that NA therapeutics are heavily modified to increase their half-life in vivo could afford a wide range of opportunities for the application of sequencing approaches based on LC-MS/MS. Their merits over established sequencing technologies used in genomics applications, which most frequently rely on the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA), have been clearly demonstrated in the context of the characterization of both natural [141,142] and drug-induced modifications [143–145]. The development of ancillary approaches, such as data dependent acquisition (DDA) and similar techniques, will be expected to further promote large scale sequencing applications. Once again, a study aimed at the LC-MS/MS characterization of natural samples could serve to exemplify the potential of these techniques in the analysis of synthetic therapeutics. This study demonstrated that the creation of an appropriate list of precursor ions to be omitted from activation (i.e., exclusion list) could greatly decrease the number of tandem MS experiments necessary to elucidate the distribution of rPTMs in transfer RNAs (tRNAs) of different microorganisms [146]. The fact that the identity of tRNA is defined by a combination of sequence information and presence of specific rPTMs offers the opportunity to predict the masses of unique digestion products with recognizable mass variations between modified and canonical versions. For this reason, it was possible to generate a list of unmodified digestion products that did not need to be sequences, thus focusing tandem analysis only on the informative modified products. The outcome demonstrated a 20% increase in the number of modified digestion products observed by LC-MS/MS analysis. This type of strategy could represent proof-of-principle for possible studies aimed at determining the sequence location of drug-induced modifications at whole transcriptome/genome levels.

Moving forward, the rapid expansion of NA therapeutics will be expected to promote also the increasing application of LC-MS and LC-MS/MS to support the elucidation of their absorption, digestion, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) characteristics. Over the years, numerous reports have demonstrated the merits of these techniques in the analysis of ON metabolites produced in vitro, or extracted from different tissues and biological fluids [147–152]. In most cases, the front-end separation step is sufficient to mitigate the deleterious effects of non-volatile metals (i.e. Na+, K+, Mg2+, etc.) present with high concentrations in biological samples, as demonstrated by the RP LC-MS characterization of phosphorothioate metabolites obtained from rat plasma, kidney, and liver extracts [147]. The study showed that the metabolites found in plasma were exclusively produced by 3’-exonucleases activity, whereas those in kidney and liver had been subjected to both 3’ and 5’degradation. In this case, the utilization of a mobile phase containing 20 mM tripropylamine and 60% 2-propanol served to minimize the incidence of metal adducts and enabled successful determinations in spite of the elevated loads of non-volatile cations in the initial samples. Alternatively, the utilization of an initial solid-phase extraction (SPE) step, which may be based on either RP [148] or weak ion exchange systems [151], can be very beneficial to achieve desalting and matrix removal. An example is provided by the investigation of the metabolism of the antisense phosphorothioate ON G3139, which involved an initial RP SPE step followed by ion pairing RP LC-MS [148]. The representative data in Figure 3 were obtained from the plasma of a human subject treated with G3139, which revealed the identity of three characteristic metabolites produced by 3’ degradation. The method was validated as a quantitative assay with a limit of quantification (LOQ) of 17.6 nM in both human and rat plasma.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative total ion chromatogram (TIC) obtained from the plasma extract of a patient treated with G3139 (5’-TCT CCC AGC GTG CGC CAT- 3’, see text). (B – D) Mass spectra of the fractions eluting with retention times of 13.90, 12.04, and 10.7 min corresponding respectively to the N-1, N-2, and N-3 metabolites generated by stepwise cleavage of the 3’ terminal nucleotides. Reproduced with permission from ref. 148.

D. Native MS analysis of drug-NA interactions

The ability to perform ESI-MS analysis under non-denaturing conditions (i.e., native MS [153–155]) offers the opportunity to investigate the binding interactions established by both NA-active drugs and NA therapeutics. Unlike most of the anticancer therapeutics discussed above, which induce permanent chemical modification of NA targets, a variety of small-molecule ligands exert their inhibitory activities by establishing specific reversible interactions (i.e., non-covalent) with the structures of interest [156–158]. Over the years, this pharmacological approach has been validated by the approval for therapy of a handful of small-molecule drugs, such as linezolid antibiotics [159–161], Ribocil [162], Branaplam (NVS-SM1) [163], SMN-C5 [164], DMA-135 [165], and benzimidazole inhibitors [166]. Classic strategies employed to discover these types of drugs involve the initial identification of putative pharmacophoric structures with promising affinity/selectivity for the target of interest, which represent the basis for building more effective binders through structure-based optimization. Various approaches have been devised for the exploration of the broadest possible chemical space, which involve the high-throughput screening of large libraries of compounds for their ability to quench or enhance the fluorescence of appropriate dyes [167–169]. While traditional spectroscopic techniques can effectively reveal the establishment of binding interactions, they usually provide no indications on the composition and stoichiometry of the ensuing complexes. In contrast, this information can be readily obtained by direct MS analysis under non-denaturing conditions, as demonstrated over the years for a variety of ligands capable of binding to single stranded [170], duplex [171–177], triplex [178], stemloop [179–181], G-quadruplex [182–189], aptamer [190–192], and i-motif structures [193]. The vast majority of these studies were made possible by the favorable energetics of the ESI process, but early reports demonstrated that also MALDI is capable of preserving the association of relatively stable double-stranded NAs [194–197] and their non-covalent complexes with proteins and peptides [198–200]. At this time, we could not find any report describing the application of this ionization technique to NA complexes with drugs or drug-like compounds. However, the judicious selection of neutral versus acidic matrixes, the absence of denaturing co-solvents/additives, and the utilization of threshold-level laser energy would be expected to facilitate these types of analyses [201].

The potential of native MS in the characterization of NA complexes was realized early on, when a combination of mild source temperature and moderate desolvation energy was demonstrated to facilitate the detection of intact duplex constructs [202,203]. These reports were readily followed by the observation of stable assemblies of duplex ONs with the antibiotics dystamicin A and actinomycin D (Scheme 1), which enabled the unambiguous determination of binding stoichiometries from characteristic mass deviations between bound and unbound species in the samples [170,171]. The early studies demonstrated the importance of maintaining proper pH and ionic strength to preserve the specific binding equilibria in solution. To this end, the utilization of traditional buffers is discouraged by the propensity of salts based on alkaline and alkaline-earth cations to produce unwanted adducts, loss of resolution, and signal suppression [16, 204 and references therein]. For this reason, different concentrations of MS-friendly ammonium acetate or bicarbonate are typically employed to keep the pH near neutral. Although less than ideal, the same salts can also serve to control the solution’s ionic strength, which is an essential determinant of binding affinity. Over the years, alternative strategies have been proposed to enable the analysis of samples containing sufficient amounts of Mg2+ to preserve its stabilizing activities on both NA structure and binding interactions [205]. One of them involved a dual-spray setup in which one of the emitters contained a chelator, which was allowed to react in the gas-phase with NA ions to strip away unwanted adducts [206]. The other involved utilizing sub-micrometric emitter tips that mitigate the incidence of adduction by controlling the size of the sprayed droplets [207]. In both cases, it was possible to finely tune the experimental conditions in such a way as to eliminate non-specific diffuse adducts from a complex of chromomycin A3 (Scheme 1) with a cognate duplex, while preserving the specific coordination of a Mg2+ equivalent necessary to stabilize the specific binding interaction (Figure 4). In similar fashion, these strategies could be readily employed to test new concepts of drug design involving specific metal-ligand interactions [208].

Figure 4.

Nanospray MS spectra of a sample containing 5 μM double-stranded DNA substrate (ds), 20 μM chromomycin A3 (CM, Scheme 1), and 0.5 mM magnesium acetate in 150 mM ammonium acetate at pH 7.0. The spectrum in panel (a) and (b) were respectively acquired by using either micrometer- or submicrometer-size emitters. The insets enlarge the m/z regions containing signals that correspond to both unbound ds substrate (labeled in blue) and full-fledged ds·(2CM·Mg) assembly (labeled in red) to highlight matching adduction patterns. The dashed box indicates the position that would be occupied by a hypothetical assembly lacking the necessary coordinated Mg2+. Reproduced with permission from ref. 207.

The stability of ligand-NA complexes can be assessed by inducing their gas-phase dissociation under controlled activation conditions (vide infra), or by determining the proportion of unbound versus bound species at equilibrium in solution. The success of these experiments hinges on ensuring that environmental and instrumental conditions do not introduce unwanted equilibrium perturbations, which is typically achieved by monitoring the effects of varying conditions on the association state of the system of interest, or testing the selected conditions on systems of known binding affinity. When this criterion is met, native MS can provide an unbiased assessment of the abundances of the various species at equilibrium, which can be in turn employed to calculate an actual dissociation constant (Kd) [209,210,180,211]. For example, the binding affinities of complexes formed by the interaction of a construct mimicking the 16S rRNA A-site with the aminoglycoside antibiotics paromomycin and tobramycin (Scheme 1) were successfully determined by following a classic titration approach [209]. The determination involved adding increasing amounts of each ligand to a constant concentration of RNA, which was set below the expected value of Kd. The concentrations of unbound/bound species present at equilibrium were determined by direct correlation with the signal intensities recorded by ESI-MS analysis. The actual values of Kd obtained by submitting these concentrations to Scatchard analysis agreed with literature values within a factor of three. This treatment benefitted from a direct knowledge of stoichiometry and binding mode afforded by the MS data, which must be instead inferred from model fitting operations when the determinations are carried out by using traditional techniques, such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [212] and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) [213]. An analogous titration scheme was implemented to determine the affinities of the complexes established by a series of stemloop domains of the HIV-1 packaging signal (ψ-RNA) with aminoglycoside antibiotics, as well as known minor groove binders, intercalating ligands, and the antineoplastic mitoxantrone (Scheme 1) [180]. In this case, however, the concentrations of species at equilibrium were calculated from the initial (total) concentration of RNA provided by UV absorbance analysis and the proportions of unbound/bound components (i.e., molar fractions) obtained from the respective signal intensities. The same quantitative treatment was applied also to the results of titration experiments carried out on the complexes of the ψ-RNA stemloops with the viral nucleocapsid (NC) protein, a nucleic acid chaperone essential to the virus lifecycle [180]. The experiments revealed the ability of aminoglycosides to induce the dose-dependent dissociation of the preformed NC-stemloop assemblies. For these ligands it was therefore possible to obtain the concentration inducing 50% inhibition (i.e., IC50) of the initial complexes in vitro.

In medicinal chemistry, the availability of accurate Kd/IC50 information can be determinant in structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies aimed at improving the performance of a promising hit. In many cases, however, ranking the properties of a developmental binder versus those of a model compound can be at least as valuable as obtaining actual Kd/IC50 values. Unlike bulk spectroscopic techniques that report only the cumulative results transpiring from all possible events taking place in solution, the MS platform affords the ability to resolve virtually all individual species in the sample, which in turn translates in the possibility to monitor multiple simultaneous equilibria. This favorable feature offers the opportunity of setting up binding competition experiments in which multiple ligands vie for the same substrate, and the signal intensity of the most abundant complex unambiguously identifies the best performer in the pool [214,215]. An illustration of this concept is provided by competition experiments involving the ψ-RNA stemloops and equimolar mixtures of vancomycin, mitoxantrone and neomycin B (Scheme 1) [180]. Titrating increasing amounts of the ligand mixture into samples containing a constant substrate concentration immediately identified neomycin B as the best binder in the group. Furthermore, the ESI-MS data revealed that two equivalents of mitroxantrone bound to the selected substrate versus only one of neomycin B at increasing concentrations, thus providing valuable insights into the putative binding modes adopted by these ligands. In contrast, no binding was observed for vancomycin even at the highest concentration tested in the study, consistent with the fact that its antibiotic activity is due to excellent ionophoric properties rather than specific RNA-binding capabilities. This molecule was purposely included in the study as a negative control meant to demonstrate that the selected experimental conditions were not conducive to non-specific aggregation and other possible artifacts that might afflict native MS analysis. The terms of the competition can be also reversed by testing one ligand against multiple putative substrates. This concept could be illustrated by a study in which a series of ligands with well-known binding modes were employed to investigate the distinctive structural features of the HIV-1 polypurine tract (PPT), a unique RNA:DNA hybrid that plays an essential role in the reverse transcription of viral RNA during the HIV-1 lifecycle [172]. In this case, constructs mimicking the wildtype RNA:DNA PPT were competed against DNA:RNA, RNA:RNA and DNA:DNA analogues. Neomycin B provided the most informative data by revealing that two separate regions of the wildtype construct exhibited significant deviations from the regular double-helical conformation. A follow up nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) study indicated that such regions contained unusual off-register base pairs, which could represent the initial binding sites for the viral reverse transcriptase [173].

Competition schemes have been implemented to screen libraries of both synthetic and natural origin. Salient regions of the 16S and 18S subunits of rRNA were the targets of screens involving series of aminoglycosides [179,216], as well as natural products present in microorganism extracts [217]. In these studies, a multitargeted approach was implemented in which one of the RNA constructs incorporated an uncharged polyethylene glycol modifier (i.e., hydrophilic tag) capable of shifting the signals of the respective complexes to a less crowded region of the spectrum. As shown in Figure 5 inset, the expedient facilitated the evaluation of the binding interactions established simultaneously by the six members of the aminoglycoside library [179]. The competition between 16S and 18S constructs served to gauge the selectivity of these ligands towards bacterial versus mammalian rRNA, respectively, which helped predict potential toxicity toward human patients. A follow up study explored the possibility that extracts of Streptomyces rimosus sp. paromomycinus might contain ligands with potential antibiotic activity against the prokaryotic 16S A-site [217]. In this case, the substrates consisted of RNA constructs mimicking the wildtype A-site of E. coli and a mutant lacking a characteristic bulge essential to aminoglycoside binding. The Streptomyces extract was initially fractionated by RP HPLC and the fractions collected in a 96-well microtiter plate. Direct infusion ESI-MS analysis was carried out after addition of the RNA substrates and a brief incubation interval to establish binding. The determinations identified a new molecule capable of binding specifically to the wildtype structure, but not to the negative-control mutant [217]. This outcome clearly substantiated the merits of combining front-end separation with high-resolution mass analysis for the screening of complex natural libraries.

Figure 5.

Mass spectrum obtained from a sample that contained constructs mimicking the A sites of 16S and 18S ribosomal RNA added with a library of six aminoglycosides: apramycin (AP), ribostamycin (RM), tobramycin (TB), bekanamycin (BK), paromomycin (PM), and lividomycin (LV) (Scheme 1). The signals free 16S and 18S constructs are labeled with their respective charge states, whereas the complexes are labeled with the respective ligand. Possible potassium adduct and instrument noise are marked with +K+ and *, respectively. Reproduced with permission from ref. 179.

E. Top-down MS analysis of drug-NA complexes

A different approach for investigating the properties of bound complexes involves activating their dissociation directly in the gas phase. A variety of strategies have been devised, which involve imparting energy to the system either in the source region during the desolvation process, or in the mass analyzer upon isolation of the selected precursor ion. The former is typically accomplished by increasing the source temperature or the desolvation energy, which is determined by the voltage applied to the sampling cone, capillary exit, nozzle-skimmer gap, or similar, depending on instrument design [218–220]. Dubbed “thermal denaturation in the gas-phase,” the process was employed to evaluate the stability of the interactions of a model ON duplex with two minor groove-binding drugs [221]. In this study, the relative intensities of unbound duplex and those of its complexes with Hoechst 33258 and netropsin (Scheme 1) were plotted as a function of cone voltage. Not only did the curves resemble very closely those traditionally obtained by using UV-spectrophotometry to follow the denaturation process (i.e., UV melting), but they also indicated that both ligands had noticeable stabilizing effects on strand association, with netropsin affording the greater stabilization. This outcome confirmed the ability of drug-NA complexes to withstand the transfer from solution to gas phase, and suggested that the detected ions retained the characteristic structural features necessary to sustain ligand binding.

The need to unambiguously discriminate actual dissociation products from free components pre-existing in solution represents a major challenge for in-source activation approaches, which might hamper unambiguous data interpretation. The implementation of classic tandem MS approaches, which involve the effective isolation of a precursor ion of interest from all the others emerging from the source, can readily overcome this challenge, while providing also the opportunity to explore different activation techniques. For example, tandem MS was successfully employed to investigate the gas-phase behavior of complexes comprising a model ON duplex and classic NA ligands, such as intercalators and groove-binders [222]. The experiments conducted in negative ion mode revealed that collisional activation could produce distinctive outcomes in which the ligand dissociated from the precursor in either neutral or anionic form, or remained attached to one of the strands upon duplex dissociation. These observations were ascribed to the interplay between the ligand’s gas-phase basicity and the coulombic repulsion (influenced by overall charge state) within the precursor ion, which determined the ability to promote charge separation processes. In contrast, the dissociation of protonated ligand was the only process observed in positive ion mode, thus pointing towards the ligand’s proton affinity as the determining factor. In similar fashion, gas-phase dissociation was employed to investigate the interactions between benzopyridoindole and benzopyridoquinoxaline drugs (Scheme 1) with both duplex and triplex DNA constructs [178]. Determining the collision energy necessary to dissociate 50% of the complex (i.e., CE50) provided an effective method for ranking the strength of the interactions established by the various ligands. The study noted the absence of any preferential binding towards AT or GC pairs and identified a common heteroaromatic core as a possible driver of selectivity towards triple-helical structures.

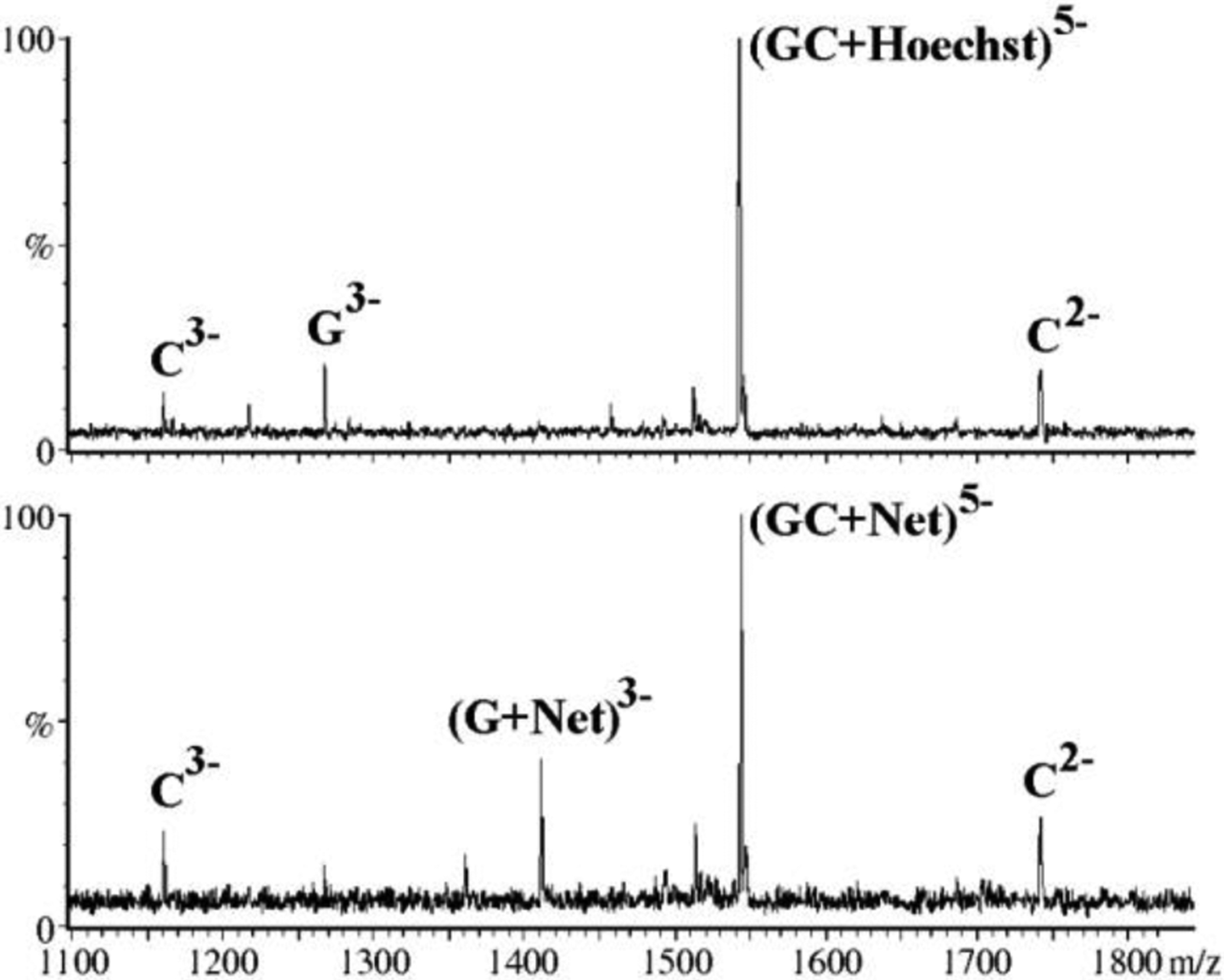

In most instances, the dissociation patterns produced by these experiments can be interpreted on the basis of salient structural features of the assembly of interest, as illustrated by an investigation of the complexes of Hoescht 33258 and netropsin (Net, Scheme 1) with a model duplex [223]. Confirming the outcomes afforded by in-source activation discussed above, collisional activation experiments highlighted the significant stabilizing effects of drug binding on strand association. However, when the applied collision energy was sufficient to overcome such stabilization, the [duplex + Hoechst 33258]5- precursor exhibited strand separation with full ligand release, whereas its [duplex + Net]5- counterpart showed the ligand clinging to one of the dissociated strands (Figure 6). In this case, the diverging behaviors were ascribed to the different hydrogen-bonding patterns inferred from the crystal structures of similar assemblies containing these drugs. Indeed, the structures revealed that Hoechst 33258 engaged in one fewer hydrogen bond with the cognate duplex than netropsin did. Furthermore, the former displayed an even distribution of hydrogen bonds with either strand, whereas the latter manifested a pronounced preference for one of them. On one hand, these observations once again supported the notion that the transfer from solution to gas phase did not significantly disrupt the structures involved in the specific binding interactions. On the other, they opened the door for the utilization of tandem MS to acquire valuable information on the structural determinants of binding.

Figure 6.

CID spectra obtained from the [duplex + Hoechst 33258]5- (top) and [duplex + netropsin]5- (bottom) precursor ions at a laboratory frame energy of 30 eV. Reproduced with permission from ref. 223.

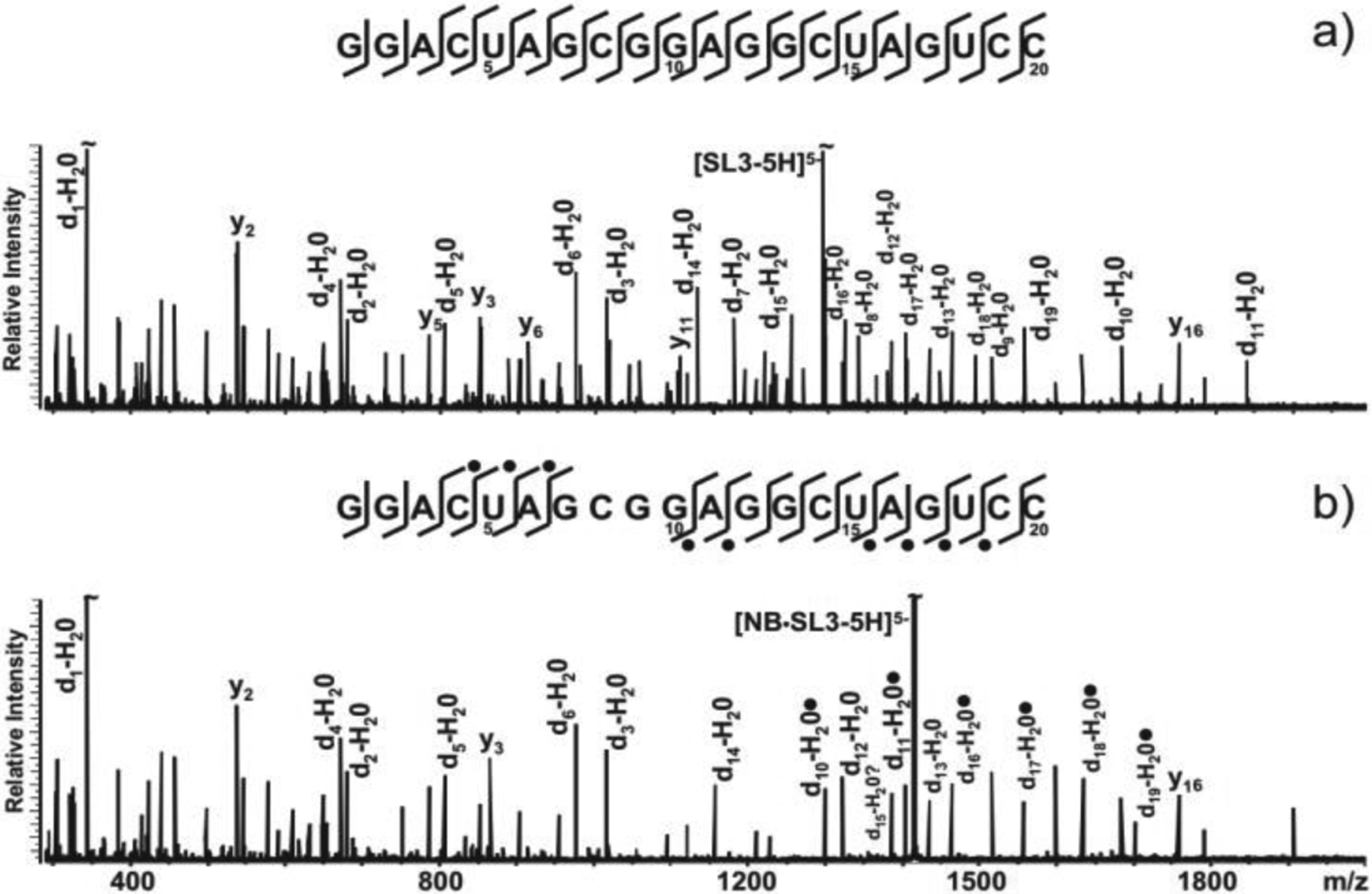

This possibility was substantiated by the observation that ligand interactions were capable of inhibiting typical backbone cleavage processes observed upon activation of NA precursor ions, thus offering the ability to map actual binding sites [172,173,179,216]. An example can be provided by the investigation of the binding modes of aminoglycoside antibiotics with the ψ-RNA stemloops of the HIV-1 genome [224]. Submitted to collisional activation, unbound constructs exhibited nearly complete ion series that covered the entire sequence, as exemplified by the SL3 sample in Figure 7a. In contrast, the corresponding complex with neomycin B (Scheme 1) produced incomplete ion series with a noticeable gap in the sequence coverage (Figure 7b). Furthermore, ligand equivalents were found attached to fragments following the gap in the series (solid dots in Figure 7b), whereas they were absent from those preceding the gap. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and computational docking experiments revealed the presence of a large negatively-charged patch on the stemloop structure, which represented an ideal binding site for the positively-charged neomycin B. The docked models showed that the patch was lined by the nucleotides corresponding to the gap in the sequence coverage identified by collisional activation. The observed protection effects, comparable to those that make solution footprinting possible, were ascribed to the cumulative action of the network of weak interactions (i.e., electrostatic, Van der Waals, and hydrogen bonds) between ligand and substrate, which masked the underlying backbone cleavages by preventing the detection of ensuing fragments as separate individual products. Similar protection effects have been observed also in protein-NA complexes [225,226] and NA higher-order structures [227,228] in what could be defined as “gas-phase footprinting” experiments.

Figure 7.

CID spectra and fragmentation patterns obtained from a) unbound SL3 and b) NB·SL3 assembly. A solid dot indicates the presence of neomycin B (NB, Scheme 1) on fragment ions. Complete d-H2O (a.k.a. c) and y series ions were observed for unbound RNA but not for its NB complex (only the more abundant ions were labeled for clarity). The G7:G10 gap in the sequence coverage was ascribed to the protection effects exerted by the ligand onto the upper stem and loop region of the stemloop structure. Reproduced with permission from ref. 224.

In addition to CID, alternative activation techniques have been evaluated for their ability to induce backbone fragmentation while preserving existing non-covalent interactions. Submitted to IRMPD, models consisting of duplex ONs and classic NA-active drugs produced dissociation patterns that matched very closely those observed upon collisional activation [229]. In both cases, complexes comprising minor groove binders and AT-rich duplexes displayed predominant strand separation, whereas those including intercalating drugs and GC-rich constructs followed ligand ejection pathways, consistent with the preference of intercalators for contiguous GC pairs and the known stabilizing effects of intercalation on helical structures. However, IRMPD featured a significant reduction of typical base losses in favor of broader distributions of sequence-informative ions (Figure 8), which enabled greater sequence coverage. The desirable outcome was attributed to the ability of controlling the conditions of IRMPD activation more finely than possible in CID experiments, in such a way as to allow for the products of an initial cleavage process to undergo further fragmentation upon absorption of additional photons. A different study examined the patterns observed when submitting G-quadruplex complexes to electron photodetachment dissociation (EPD) [189]. The approach required the utilization of supercharging agents to increase the charge state of the precursor ions, which was necessary to promote the formation of the radicals responsible for bond cleavage. The activation process proved to be sufficiently gentle to preserve weak interactions with specific G-quadruplex ligands, such as 360A and PhenDC3 (Scheme 1), as well as those with the K+ equivalents that constitute integral components of the G-quadruplex structure. Also in this case, ligand binding exerted sufficient protection on the underlying nucleotides to produce the characteristic gaps of sequence coverage corresponding to the specific binding sites. Based on these results, it is not difficult to predict that the possibility of obtaining direct information on the determinants of target recognition will continue to be a powerful drive for the further development of these types of approaches.

Figure 8.

Evaluation of the outcomes observed when submitting the [M − 6H]6- ion of the complex of nogalamycin (Scheme 1) with a model duplex deoxy-ON to either (A) collisionally activated dissociation (CAD) or (B) infrared multi-photon dissociation (IRMPD). The energy imparted to the precursor ion was modulated by varying either the collision voltage (in CAD) or the duration of the laser pulse (in IRMPD). As shown in the legend, fragment types were grouped as single-stranded products, single-stranded with bound drug, deprotonated drug, drug-free duplex, and sequence ions. Reproduced with permission from ref. 229.

F. Investigating the possible effects of drugs on NA structure and dynamics

Detailed information on the structural effects of modifiers on target substrates, regardless of their covalent or non-covalent nature, can significantly accelerate the progress of SAR studies. Established high-resolution techniques, such as X-ray diffraction, NMR spectroscopy, and now cryo-electron microscopy, represent proven choices for the structural determination of chemically modified NAs. In spite of the remarkable advances experienced by such techniques over the years, their implementation remains as sample-demanding, labor-intensive, and resource-consuming as ever. These considerations have fueled continued interest in complementary low-resolution techniques, which might be capable of providing the preliminary information necessary to narrow the scope of high-resolution analysis only to the most compelling samples. The MS platform has been the focus of much of this interest due to the modest sample demands, the ability to deal with sample heterogeneity, and most of all its excellent versatility. Different MS-based strategies have been explored over the years, which are capable of providing information on the structure and dynamics of NA samples, including hydrogen-deuterium exchange [230–233], chemical/biochemical probing [73,83,234–236], and direct top-down analysis [227,228]. The most promising approach, however, is arguably represented by ion mobility (IM) mass spectrometry, which is capable of providing direct information on structure and dynamics by virtue of the close relationship between an ion’s 3D structure and its collisional cross section (CCS) [237–239]. In this family of techniques, the interactions between ions of interest and background gas affect their motion in either constant or oscillating electric fields, which determine their travel time through the analyzer, or the actual voltage necessary to see them through. In either case, the actual experimental data is translated into CCS values that are indicative of the charge and overall shape exhibited by the ions during the experiment. Such values are then compared with those predicted by different computational approaches, or those observed upon varying determinant factors, such as sample pH, ionic strength, source temperature, desolvation energy, collision energy, and others, which may be capable of altering the analyte structure. Prominent among such factors are chemical modification and ligand binding.

The application of IM techniques to the investigation of drug-NA complexes is still in its infancy, but few available reports have already established the potential of this approach. For example, the combination of native MS and IM analysis was successfully employed to investigate the effects of binding on the conformation of selected ON aptamers, including an adenosine-binding aptamer (ABA), a L-argininamide-binding aptamer (LABA), and a cocaine-binding aptamer (CBA) [191]. Upon incubation with the respective ligand, the charge state distribution afforded by the constructs displayed characteristic shifts toward lower charging, which suggested the adoption of more compact conformations stabilized by the specific binding interactions. In the case of ABA, however, the IM data obtained from the lower charge states of the unbound form revealed the presence of two distinctive conformational states in the absence of ligand (Figure 9 a–c). Upon addition of 5’-amino-3’-deoxyadenosine (Scheme 1), one of them experienced noticeable abundance increases without significant variations of IM behavior, which were consistent with the presence of a preformed binding-competent conformation in solution. The fact that the ligand promoted substrate selection rather than folding processes supported the rigid-binding model suggested by prior spectroscopy studies. In similar fashion, the concerted application of native MS and IM analysis provided detailed information on the binding properties of the cocaine- and quinine-binding aptamers [192]. In this case, the IM data indicated that the latter underwent a small ligand-induced conformational change, which exhibited an inverse correlation with binding affinity. In drug discovery, elucidating the conformational effects of ligand-substrate recognition could provide very valuable insights to drive the design of better ligands and more potent inhibitors.

Figure 9.

Arrival time distributions (ATD) obtained from selected ions of free/bound aptamers with their respective ligands: ABA (a-c), LABA (d-f), and CBA (g-i). ATDs of unbound aptamer ions are shown as blue shaded curves, whereas those of their complexes with one, two, and (where applicable) three equivalents are shown as colored curves (see legend above the panels). The ion charge states are indicated in the top-right corner of each plot. Reproduced with permission from ref. 191.

G. Conclusions

The capabilities showcased in this brief overview rationalize the ubiquitous contributions of the MS platform to all phases of the journey undertaken by any successful NA drug from laboratory to bedside, progressing from initial discovery to the development of putative leads, from the gathering of necessary regulatory data to actual manufacturing operations. The selected examples have shown that, with proper experimental design, this platform can readily provide the identity of NA analytes and reveal the presence of both covalent and non-covalent modifications. This information can in turn afford extensive insights into the mechanisms of action of modifiers, which are essential to understand the determinants of their inhibitory activity, as well as the causes of possible toxicity. The reach of the platform is not limited to model systems contained in a mere test tube, but extends to complex biological samples that carry the marks of the activity of putative therapeutics on whole living organisms, thus enabling the elucidation of their entire metabolic fates. The capacity to acquire valid quantitative data translates into the ability to support the pharmacokinetics studies necessary to drive development and obtain essential information for securing regulatory approval. Further proof of the utmost versatility exhibited by MS in NA analysis is provided by its extensive foothold in other areas of public health involving these biopolymers, such as the ever expanding fields of genetic screening [240–242] and disease diagnostics [243–245]. Finally, the incessant growth of applications outside the traditional laboratory settings, such as those in support of the manufacturing of NA therapeutics, represents the ultimate affirmation of the capabilities and robustness of this analytical platform.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this review was provided to D.F. by NIH-NIAID [R21 AI133617], NIH-NIGMS [R01 GM123050 and R01 GM121844], and NIH- NIDA [R01 DA04611].

List of acronyms:

- ABA

adenosine-binding aptamer

- ADME

adsorption, digestion, metabolism, and excretion

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CAD

collisionally activated dissociation

- CBA

cocaine-binding aptamer

- CE

capillary electrophoresis

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- DDA

data dependent acquisition

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EC

electron capture

- EPD

electron photodetachment dissociation

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FAB

fast atom bombardment

- FRET

Förster (or Fluorescence) resonance energy transfer

- FTICR

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

- GC

gas chromatography

- HFIP

1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- IM

ion mobility

- IP

ion-pair

- IRMPD

infrared multiphoton dissociation

- ITC

isothermal calorimetry

- Kd

dissociation constant

- LABA

L-argininamide-binding aptamer

- LC

liquid chromatography

- LNA

locked nucleic acid

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- MD

molecular dynamics

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NA

nucleic acid

- NC

nucleocapsid

- NGS

next generation sequencing

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- ON

oligonucleotide

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PAH

polyaromatic hydrocarbons

- PNA

peptide nucleic acid

- PPT

polypurine tract

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- RP

reversed-phase

- rPTM

RNA post-transcriptional modification

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- SAR

structure activity relationship

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SMM

small molecule microarray

- SORI

sustained off-resonance irradiation

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- TAR

transactivation response

- TEA

triethylammonium

- tRNA

transfer RNA

- UVPD

ultraviolet photodissociation

- ψ-RNA

HIV-1 packaging signal

Author Biographies:

Thomas Kenderdine received his B.S. degree in Chemistry with minor in Mathematics from James Madison University (Harrisonburg, VA) in 2008 and subsequently held a six-year career as an industry analytical chemist using mass spectrometry. He is currently a PhD candidate under the mentorship of Prof. Daniele Fabris at the University of Connecticut. His research focuses on the development of new technologies for high-throughput identification and characterization of putative RNA therapeutics using high-resolution and ion mobility mass spectrometry.

Dr. D. Fabris is the Harold S. Schwenk Sr. Distinguished Chair in Chemistry and a Professor in the Department of Chemistry of the University of Connecticut. In the late Eighties, as an eager young student at the University of Padova (Italy), he was introduced to mass spectrometry (MS) by Dr. P. Traldi at the National Research Council in Padova, while working on a thesis project aimed at the characterization of the degradation products of preservatives used in cosmetics. In 1992, a move to the University of Maryland Baltimore County (Baltimore, MD) to work as a post-doctoral fellow with Dr. C. Fenselau marked a conspicuous change of direction towards the development of MS approaches for the characterization of proteins and their complexes with ligands and metals. In 1999, as a new faculty at University of Maryland Baltimore County, he started to establish an independent program aimed at the development of enabling MS technologies for the investigation of the structure-function relationships in viral RNA systems. In 2010, he moved to the University at Albany (SUNY) to become one of the founding members of The RNA Institute. At University of Connecticut since 2020, his laboratory specializes in the development of MS-based technologies for epitranscriptomics analysis and the investigation of the effects of RNA modifications of both endogenous and exogenous origin on the structure/dynamics of viral RNA.

References

- 1.Gilman A & Philips FS: The Biological Actions and Therapeutic Applications of the B-Chloroethyl Amines and Sulfides. Science 103, 409–436 (1946). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilman A: The initial clinical trial of nitrogen mustard. The American Journal of Surgery 105, 574–578 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oronsky BT, Reid T, Knox SJ & Scicinski JJ: The Scarlet Letter of Alkylation: A Mini Review of Selective Alkylating Agents. Translational Oncology 5, 226–229 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.More GS, Thomas AB, Chitlange SS, Nanda RK & Gajbhiye RL: Nitrogen Mustards as Alkylating Agents: A Review on Chemistry, Mechanism of Action and Current USFDA Status of Drugs. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry- Anti-Cancer Agents) 19, 1080–1102 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Childs-Disney JL & Disney MD: Approaches to Validate and Manipulate RNA Targets with Small Molecules in Cells. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 56, 123–140 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermann T: Small molecules targeting viral RNA: Small molecules targeting viral RNA. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 7, 726–743 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warner KD, Hajdin CE & Weeks KM: Principles for targeting RNA with drug-like small molecules. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, 547–558 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamecnik PC & Stephenson ML: Inhibition of Rous sarcoma virus replication and cell transformation by a specific oligodeoxynucleotide. PNAS 75, 280–284 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson ML & Zamecnik PC: Inhibition of Rous sarcoma viral RNA translation by a specific oligodeoxyribonucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 75, 285–288 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dias N & Stein CA: Antisense Oligonucleotides: Basic Concepts and Mechanisms. Mol Cancer Ther 1, 347–355 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma VK & Watts JK: Oligonucleotide therapeutics: chemistry, delivery and clinical progress. Future Med Chem 7, 2221–2242 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanton MG & Murphy-Benenato KEin RNA Therapeutics (Garner AL) 237–253 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).doi: 10.1007/7355_2016_30 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng Y, Li C, Yang T, Hu B, Zhang M, Guo S, Xiao H, Liang X-J & Huang Y: The challenge and prospect of mRNA therapeutics landscape. Biotechnology Advances 40, 107534 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCloskey JA in Mass Spectrometry in the Health and Life Sciences, Burlingame AL, Castagnoli N, eds. 521–546 (Elsevier, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limbach PA, Crain PF & McCloskey JA: Characterization of oligonucleotides and nucleic acids by mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 6, 96–102 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordhoff E, Kirpekar F & Roepstorff P: Mass spectrometry of nucleic acids. Mass Spectrom. Rev 15, 67–138 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou S & Cook KD: Protonation in electrospray mass spectrometry: wrong-way-round or right-way-round? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 11, 961–966 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamashita M & Fenn JB: Electrospray ion source. Another variation on the free-jet theme. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 88, 4451–4459 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilm M & Mann M: Analytical properties of the nanoelectrospray ion source. Anal. Chem 68, 1–8 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Ido H, Yoshida Y & Yoshida T: Detection of high mass molecules by laser desorption time-of-flight mass spectrometry. in Proceedings of the Second Japan-China Joint Symposium on Mass Spectrometry (Matsuda H & Liang X-T) 185–188 (Bando Press, Osaka, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karas M, Bachmann D, Bahr U & Hillenkamp F: Matrix-assisted ultraviolet laser desorption of non-volatile compounds. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Proc 78, 53–68 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barber M, Bordoli RS, Sedgwick RD & Tyler AN: Fast atom bombardment of solids (F.A.B.): a new ion source for mass spectrometry. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 325–327 (1981).doi: 10.1039/C39810000325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCloskey JA & Crain PF: Progress in mass spectrometry of nucleic acid constituents: Analysis of xenobiotic modifications and measurements at high mass. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Proc 118/119, 593–615 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manchester DK, Weston A, Choi JS, Trivers GE, Fennessey PV, Quintana E, Farmer PB, Mann DL & Harris CC: Detection of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-DNA adducts in human placenta. PNAS 85, 9243–9247 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gangl ET, Turesky RJ & Vouros P: Determination of in Vitro- and in Vivo-Formed DNA Adducts of 2-Amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline by Capillary Liquid Chromatography/Microelectrospray Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol 12, 1019–1027 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Apruzzese WA & Vouros P: Analysis of DNA adducts by capillary methods coupled to mass spectrometry: a perspective. Journal of chromatography 794, 97–108 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villalta PW & Balbo S: The Future of DNA Adductomic Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 18, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo J & Turesky RJ: Emerging Technologies in Mass Spectrometry-Based DNA Adductomics. High Throughput 8, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giese RW: Detection of DNA Adducts by Electron Capture Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol 10, 255–270 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farmer PB, Brown K, Tompkins E, Emms VL, Jones DJL, Singh R & Phillips DH: DNA adducts: Mass spectrometry methods and future prospects. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 207, 293–301 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tretyakova N, Goggin M, Sangaraju D & Janis G: Quantitation of DNA adducts by stable isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol 25, 2007–2035 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudley E, Lemiere F, Van Dongen W, Esmans E, El-Sharkawi AM, Games DE, Brenton AG & Newton RP: Urinary modified nucleosides as tumor markers. Nucleosides, nucleotides & nucleic acids 22, 987–9 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuytten R, Lemière F, Van Dongen W, Witters E, Esmans EL, Newton RP & Dudley E: Development of an On-Line SPE-LC–ESI-MS Method for Urinary Nucleosides: Hyphenation of Aprotic Boronic Acid Chromatography with Hydrophilic Interaction LC–ESI-MS. Anal. Chem 80, 1263–1271 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bransfield LA, Rennie A, Visvanathan K, Odwin S-A, Kensler TW, Yager JD, Friesen MD & Groopman JD: Formation of Two Novel Estrogen Guanine Adducts and HPLC/MS Detection of 4-Hydroxyestradiol-N7-Guanine in Human Urine. Chem. Res. Toxicol 21, 1622–1630 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips DH, Carmichael PL, Hewer A, Cole KJ, Hardcastle IR, Poon GK, Keogh A & Strain AJ: Activation of tamoxifen and its metabolite α-hydroxytamoxifen to DNA-binding products: comparisons between human, rat and mouse hepatocytes. Carcinogenesis 17, 89–94 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes MT, Bartley J, Parsons PG, Eaglesham GK & Prakash AS: Mechanism of Action of Fotemustine, a New Chloroethylnitrosourea Anticancer Agent: Evidence for the Formation of Two DNA-Reactive Intermediates Contributing to Cytotoxicity. Biochemistry 36, 10646–10654 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wickham G, Iannitti P, Boschenok J & Sheil MM: The observation of a hedamycin-d(CACGTG)2 covalent adduct by electrospray mass spectrometry. FEBS Lett 360, 231–4 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richter S, Gatto B, Fabris D, Takao K, Kobayashi S & Palumbo M: Clerocidin alkylates DNA through its epoxide function: evidence for a fine tuned mechanism of action. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 5149–56 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richter SN, Menegazzo I, Fabris D & Palumbo M: Concerted bis-alkylating reactivity of clerocidin towards unpaired cytosine residues in DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 32, 5658–5667 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richter S, Fabris D, Binaschi M, Gatto B, Capranico G & Palumbo M: Effects of common buffer systems on drug activity: the case of clerocidin. Chem. Res. Toxicol 17, 492–501 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Troujman H & Chottard J-C: Comparison between HPLC and Capillary Electrophoresis for the Separation and Identification of the Platination Products of Oligonucleotides withcis-[Pt(NH3)2(H2O)2]2+and [Pt(NH3)3(H2O)]2+. Analytical Biochemistry 252, 177–185 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garaguso I, Halter R, Krzeminski J, Amin S & Borlak J: Method for the rapid detection and molecular characterization of DNA alkylating agents by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 82, 8573–8582 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Limbach PA: Indirect mass spectrometric methods for characterizing and sequencing oligonucleotides. Mass Spectrom. Rev 15, 297–336 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]