Abstract

Hemostasis is a crucial step in cardiac surgery which determines postoperative outcomes. Tissue sealants and glues are necessary to achieve hemostasis in situations where conventional methods are unsuccessful. BioGlue, a commonly used topical hemostatic agent, has been reported to cause systemic embolic complications. We report a case of cerebral embolic shower following the use of BioGlue for posterior aortic suture line bleeding in a 49-year-old lady who underwent triple valve surgery. This report brings to light a rare but devastating complication of BioGlue usage in the present era of complex aortic surgeries. We also postulate a mechanism for BioGlue embolization.

Keywords: Tissue sealants, Glues, BioGlue embolism, Stroke

Introduction

BioGlue (CryoLife, Inc., Kennesaw, GA), composed of 45% purified bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10% glutaraldehyde, is a commonly used and proven surgical hemostat [1, 2]. We report a case of cerebral embolic shower after using BioGlue to manage a posterior aortic suture line bleed during triple valve surgery.

Case report

A 49-year-old lady, with rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus, was diagnosed with rheumatic heart disease, severe mitral regurgitation, moderate aortic regurgitation, moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40%. She was in atrial fibrillation with no intracardiac thrombus. She underwent aortic valve replacement with a 21-mm St. Jude Medical® mechanical valve (St. Jude Medical Inc., Minneapolis, MN), mitral valve repair with a 34-mm Carpentier-Edwards Physio II (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) annuloplasty ring, and tricuspid valve repair with a 32-mm MC3 (Edwards Lifesciences, LLC, Irvine, CA, USA) annuloplasty ring. On table evaluation revealed thickened, non-calcific aortic and mitral valve leaflets with fused commissures suggestive of rheumatic etiology. Following aortic cross-clamp release, there was bleeding from the aortic suture line posteriorly which could not be controlled with pledgetted polypropylene sutures from outside. The posterior tear was probably due to extension of the aortotomy incision while placing the mechanical aortic valve. The aorta was re-clamped, aortotomy was opened, and the posterior tear was repaired from the inside of the aorta with continuous running 5-0 polypropylene sutures. The aortotomy was closed and the cross-clamp was released. There was minimal persistent bleeding from the posterior aorta. BioGlue was applied as a film over the posterior aortic suture line and the transverse sinus was packed with oxidized cellulose polymer. Bleeding was controlled successfully and the patient was weaned off cardiopulmonary bypass. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was satisfactory. The patient was unresponsive for 48 h. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angiography (MRA) of the brain revealed multiple punctate scattered foci of acute infarcts in the bilateral frontal lobe, parietal lobe, centrum semiovale, right occipital lobe, frontal periventricular region, bilateral caudate nuclei, left lentiform nucleus, left thalamus, and splenium of the corpus callosum suggestive of an embolic shower (Fig. 1). Considering the infarct extent and her immediate postoperative status, she was not a candidate for neuro-intervention. A computed tomography (CT) of the brain repeated 72 h later revealed no interval increase in the infarct extent. She remained comatose and was tracheostomized on the seventh postoperative day. She regained consciousness on the fifteenth postoperative day. Repeat MRI done a month later revealed no interval change. With intense neuro-rehabilitation and physiotherapy over the following 6 weeks, she progressed remarkably and was weaned off the ventilator, and the tracheostomy was decannulated on the 59th postoperative day. She was discharged with no residual neurological deficits on the 61st postoperative day. She remained neurologically normal at her 6-month follow-up.

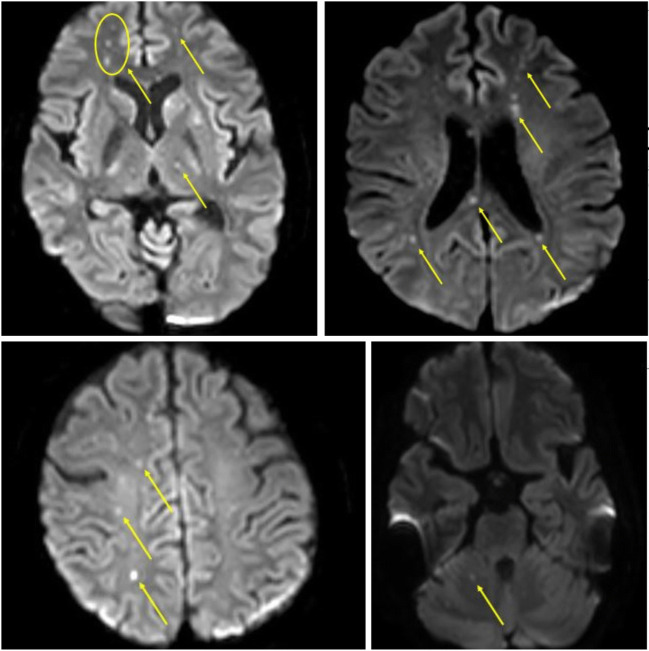

Fig. 1.

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) of the brain showing extensive multifocal cerebral and cerebellar infarcts (yellow arrows)

Discussion

Hemostasis after cardiac surgery can be challenging. Topical hemostatic agents are frequently used as adjuncts to control bleeding [3]. Glutaraldehyde present in BioGlue covalently bonds the BSA molecules to each other and the tissue proteins at the repair site, creating a mechanical seal independent of the coagulation cascade. Embolic complications to coronaries and pulmonary arteries caused by BioGlue are known [4, 5]. Cerebral embolization of gelatin-resorcinol-formaldehyde (GRF) glue was reported in 1995 as a postmortem finding following surgery for aortic dissection with possible mechanisms being direct spillage into the true lumen, escape through dissection re-entry sites into the true lumen, or leakage through anastomotic needle holes [6]. Intracardiac and intravascular sources of cerebral embolism were ruled out preoperatively in our patient by multi-modality imaging. Preoperative TEE and intraoperative evaluation showed no intracardiac thrombi. CT aortogram showed a clean aorta with no calcification (Fig. 2). MRA demonstrated a normal carotid arterial system (Fig. 3). Aortic cross-clamp was released after standard de-airing maneuvers under TEE guidance to obviate air embolism. There were no episodes of hypotension during the intraoperative or postoperative period. Postoperative MRA showed no intravascular air pockets and persistence of blooming artifact in the immediate and follow-up MRA makes air embolism unlikely. The diagnostic value of MRA diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in detecting air embolism is reported in several case studies [7, 8]. So, the potential cause of embolic shower in our patient is likely to be BioGlue, which has been proven to migrate from outside the aorta into the lumen through the suture needle holes, more commonly in native aorta (as in our case) than in synthetic grafts [9]. We postulate a mechanism for BioGlue embolization leading to cerebral embolic shower. The Venturi effect created by the high-velocity laminar blood flow in the ascending aorta would create a negative pressure adjacent to the rent in the ascending aorta which would cause the BioGlue to be sucked along the suture lines intraluminally and embolize in fragments as they come in contact with the bloodstream. The embolic shower, though multicentric, did not affect a substantial portion of any particular functional area of the brain. The function of the small infarcted areas was probably taken over by the surrounding neural tissue by virtue of neuroplasticity which aided her full functional recovery.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of computed tomography of the aorta and the arch vessels showing no wall calcification or atheromatous plaques. The left vertebral artery is seen arising as a direct branch of the arch (yellow arrow)

Fig. 3.

Preoperative magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the neck vessels demonstrating a normal flow with no luminal stenosis

Conclusion

It is prudent to exercise certain precautions—BioGlue should always be applied on the outer surface of the aorta after repairing the tear when the aorta is cross-clamped, use of a wet gauze in the aortic lumen to receive the dissipated BioGlue particles, and giving a thorough wash before releasing the cross-clamp. It is not advisable to use BioGlue when there is active bleeding. BioGlue is an important tool in the armamentarium of cardiovascular surgeons. However, it is important to take necessary precautions to avoid disastrous complications.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Venkatesa Kumar Anakaputhur Rajan and Srikanth Kasturi. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Statement of human and animal rights

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee (Narayana Health Academic Ethics Committee - letter no. NHH/AEC-CL-2021-686 dated 14.05.2021). The procedures used in the study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Waiver of informed consent was approved by the institutional ethics committee (NHAEC).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coselli JS, Bavaria JE, Fehrenbacher J, Stowe CL, Macheers SK, Gundry SR. Prospective randomized study of a protein-based tissue adhesive used as a hemostatic and structural adjunct in cardiac and vascular anastomotic repair procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:243–252. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao H-H, Torchiana DF. BioGlue: albumin/glutaraldehyde sealant in cardiac surgery. J Card Surg. 2003;18:500–503. doi: 10.1046/j.0886-0440.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnard J, Millner R. A review of topical hemostatic agents for use in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsutera R, Kume K, Yamato M, et al. BioGlue® coronary embolism during open heart surgery. J Cardiol Cases. 2014;10:78–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubio Alvarez J, Sierra Quiroga J, Martinez de Alegria A, Delgado Dominguez C. Pulmonary embolism due to biological glue after repair of type A aortic dissection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:650–651. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.261933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrel T, Maurer M, Tkebuchava T, Niederhäuser U, Schneider J, Turina MI. Embolization of biologic glue during repair of aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1118–1120. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)97585-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaichi Y, Kakeda S, Korogi Y, et al. Changes over time in intracranial air in patients with cerebral air embolism: radiological study in two cases. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:491017. doi: 10.1155/2015/491017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang SR, Choi SS, Jeon SJ. Cerebral air embolism: a case report with an emphasis of its pathophysiology and MRI findings. Investig Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;23:70–74. doi: 10.13104/imri.2019.23.1.70. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeMaire SA, Carter SA, Won T, Wang X, Conklin LD, Coselli JS. The threat of adhesive embolization: BioGlue leaks through needle holes in aortic tissue and prosthetic grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]