Abstract

Sternal dehiscence and sternal wire fractures are of significant concern for patients post cardiac surgery. Right ventricular laceration resulting from injury secondary to fractured sternal wires is a rare cause of life-threatening postoperative hemorrhage. A 68-year-old male presented for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Postoperatively, he experienced an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) which initially responded to medical treatment. While mobilizing, the patient experienced acute hemodynamic decompensation. Chest X-ray revealed a new left pleural effusion and a bedside echocardiogram revealed significant pericardial effusion. The patient was taken urgently for re-exploration with a diagnosis of cardiac tamponade. All sternal wires were found to be fractured and a right ventricular laceration was identified. The laceration was repaired primarily with sutures and the sternum was closed with reinforced sternal wires. The patient recovered well postoperatively and was discharged without further complication. Postoperative hemorrhage is a known complication of cardiac surgery but is rarely caused by laceration secondary to sternal wire fracture. Alternative sternal closure techniques should be considered in high-risk groups of patients. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for patients with sternal dehiscence. Furthermore, these patients should be monitored closely and definitive management implemented immediately when sternal wire fracture and resulting injury are suspected.

Keywords: Heart surgery, Right ventricle, Laceration, Complication, Sternal wire

Background

Resternotomy for bleeding and cardiac tamponade following coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) remains as high as 2–6% [1, 2]. This remains a significant complication leading to prolonged cardiovascular intensive care unit (ICU) stay. Resternotomy patients have been found to experience mortality rates as high as 22% [3]. The most common causes of bleeding and cardiac tamponade post cardiac surgery include coagulopathy or surgical hemostasis, while report of right ventricular (RV) laceration secondary to sternal wire fracture is exceedingly rare [4].

Case report

A 68-year-old male presented with 6 months of progressive exertional chest pain radiating to the neck. His past medical history included diabetes type II, myocardial infarction 20 years prior, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), gastroesophageal reflux disease, gout, dyslipidemia, and a retinal detachment repair. He was found to have three-vessel coronary artery disease on coronary angiography and subsequently underwent triple CABG using left internal mammary artery and saphenous vein grafts via median sternotomy. The sternum was closed using six No. 6 steel wires tied together in a figure-of-8 fashion, which is the standard closure technique for sternotomy at this center. This technique includes tying pairs of wires together at each end before tying them together at the midline at three points. The chest tubes drained 410 ml in total and were removed. The patient was stable and was transferred from the ICU to the ward.

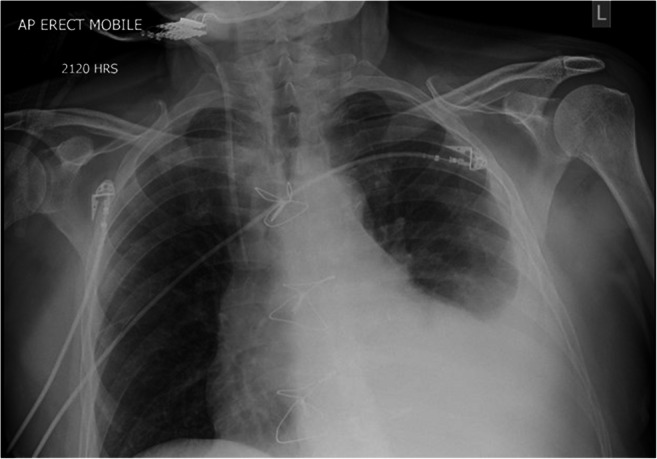

On postoperative day four, the patient was transferred back to the ICU due to increasing respiratory requirements, in what appeared to be a COPD exacerbation. The patient initially improved with medical therapy. On postoperative day six, the patient’s sternum was noted to be unstable on physical examination, with no evidence of sternal wound infection. Chest X-ray revealed a single fractured sternal wire (Fig. 1). The patient was scheduled for repair of his sternal dehiscence the following day. While awaiting reoperation, the patient was ambulating with minimal assistance and developed sudden-onset shortness of breath, became pale with cool extremities, and had bleeding from his sternal incision. Urgent repeat chest X-ray showed a new left pleural effusion (Fig. 2). A bedside echocardiogram was immediately ordered to rapidly assess the new bleeding. The echocardiogram showed a significant pericardial effusion. The patient was resuscitated with fluids, received two units of packed red blood cells (pRBC) for significant blood loss, and was started on norepinephrine for hemodynamic support. He was then taken emergently to the operating room for re-exploration. On re-exploration, there were large mediastinal clots. Contrary to the X-ray findings, all sternal wires were found to be fractured with a laceration injury to the free wall of the RV. The laceration was successfully repaired using a pledgeted 4-0 polypropylene suture. The pericardium was left open and the sternum was closed using the same figure-of-8 method, with 6 sternal wires and was reinforced with 4 parasternal wires. The patient was transfused with a single unit of pRBC intra-operatively and was transferred to the ICU with stable hemodynamics. He was successfully extubated the next day and discharged home 15 days after his initial procedure.

Fig. 1.

Inferior sternal wire fracture seen on chest X-ray following COPD exacerbation

Fig. 2.

Left pleural and pericardial effusions seen on chest X-ray

Discussion

Early postoperative hemorrhage in cardiac surgical patients may result from a number of causes including the effect of hemodilution and hypothermia, inadequate reversal of heparin, thrombocytopenia, impaired platelet function or the use of antiplatelet agents postoperatively, fibrinolysis, and iatrogenic causes such as removal of pacing wires [4, 5]. However, RV laceration from a fractured sternal wire is rare and may occur at any time in the postoperative period, resulting in acute or delayed hemorrhage and potential cardiac tamponade. Cases of sternal wire fracture resulting in life-threatening bleeding are uncommon and require rapid identification with appropriate intervention to address the injury. Therefore, a high index of suspicion must be maintained. Once a sternal wire fracture is suspected, immediate immobilization of the patient is essential to prevent further injury. Rapid imaging with chest X-ray and ultrasound helps make the diagnosis and assess the severity of bleeding. In the case of hemorrhage and hemodynamic decompensation, management of clinical condition may include inotropic support, fluid bolus, and blood transfusion in severe cases to maintain hemodynamic stability until surgical intervention can be taken. Intervention in severe cases often involves removal of fractured wires, repair of any lacerated structures, and closure of the sternum. Inspection of the fractured wire may be informative in identifying possible causes of fracture such as over twisting or wire damage. This case has demonstrated an example of successful early identification and management of bleeding secondary to sternal wire fracture.

There are different methods used for sternotomy closure including a series of wires or a figure-of-eight method. With all types of sternal closure, there is some movement of the sternal halves under physiological loads, but with regimented sternal precautions, complications are minimal. Sternal wires are produced from steel which has a material yield or failure strength, which if surpassed leads to deformities of the material. If sternal wires are to remain the gold standard for sternotomy closure, new techniques and materials for sternal closure must be trialed to ensure tensile strength is not surpassed, especially for patients at higher risk for sternal dehiscence.

Risk factors for sternal dehiscence include COPD, re-operative surgery, renal failure, diabetes, chronic steroid use, morbid obesity, concurrent infection, and immunosuppression. This patient presented with an existing diagnosis of COPD and diabetes which increases risk through additional load on the sternum from chronic cough and poor wound healing secondary to diabetes. These factors bring to question whether an alternative method should have been used as primary closure. Of note, this patient did not have additional risk factors for sternal dehiscence, such as steroid use and had normal weight preoperatively, which reduced the likelihood of the patient requiring an alternative or reinforced sternal closure at primary surgery.

With any sternal closure technique, selection of the appropriate sternal wire size, using the right number of wires for the size of the patient’s sternum, careful approximation of the sternum, and avoiding over-tightening of wires are important factors for a strong sternal closure. Alternative materials also exist for sternal closure. ZipFix (Johnson and Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) is a product consisting of polyetheretherketone band implants placed around the sternum in a similar fashion to interrupted sternal wires that provides dispersed tension across the band and sternum. ZipFix is one potential alternative to traditional sternal wires. A 1-year follow-up of the ZipFix trial demonstrated advantages over traditional sternal wire closure with reduced pain and incidence of sternal dehiscence postoperatively [6]. Recent studies suggest that rigid plate fixation may lead to reduced sternal complications in high-risk patients, improved perioperative survival, decreased length of hospital stay, and improved pain and activity management with improved osteosynthesis [7, 8]. Other innovative techniques of sternal closure have been discussed such as parasternal wire techniques, reinforced wires, crisscrossing wires, sternal plating, and cables with varying degrees of advantage over the traditional interrupted sternal wire technique [7, 9, 10]. Modified or reinforced sternal wire techniques and alternate sternal closure materials should be considered for patients at higher risk of sternal dehiscence based on preoperative risk and institutional experience. Ensuring sternal precautions are followed in the postoperative period will aid in reducing strain on the sternal wires and reduce risk of wire fracture. The establishment of institutional protocols for high-risk patients may aid in ensuring patients at increased risk for sternal wire fracture receive the optimal sternal closure. Finally, a high index of suspicion for sternal wire fracture should be maintained for post-cardiac-surgery patients presenting with sternal instability and acute hemodynamic decompensation.

Conclusions

Although the patient described in this case report was initially stable, the patient experienced acute decompensation once the fractured sternal wire caused a laceration to the right ventricle. Fortunately, the patient was in the ICU for respiratory concerns allowing for immediate investigation, stabilization, and surgical intervention. Alternative techniques and materials have been described for sternal closure in order to address the limitations of current sternal wires and placement techniques. Several studies have found advantages in alternative approaches to sternal closure, and these techniques should be considered for patients at high risk for sternal dehiscence or for those that have experienced sternal wire fracture and undergone revision. Further investigation and innovation are required to identify superior approaches to sternal closure. Furthermore, a high index of suspicion must be maintained for sternal wire fracture and sternal dehiscence. The development of protocols to recognize and manage sternal wire fractures with sternal dehiscence may result in increased rates of early detection and reduced rates of complications for patients.

Authors contribution

DO, AB: conception, design, writing—original, approval of article

RE, CD, IA: conception, design, writing—revisions, approval of article

Funding

No funding support was provided for this case report.

Data availability

All of the relevant data is available within the manuscript and its supplements.

Declarations

Ethics Committee approval

Not applicable for case report.

Informed consent

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the subject of this case report at the time of surgery to publish this case, and the manuscript has been completely anonymized to protect the identity of the patient.

Statement of human and animal rights

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dacey LJ, Munoz JJ, Baribeau YR, et al. Reexploration for hemorrhage following coronary artery bypass grafting: incidence and risk factors. Arch Surg. 1998;133:442–447. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranucci M, Bozzetti G, Ditta A, Cotza M, Carboni G, Ballotta A. Surgical reexploration after cardiac operations: why a worse outcome? Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1557–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unsworth-White MJ, Herriot A, Valencia O, et al. Resternotomy for bleeding after cardiac operation: a marker for increased morbidity and mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:664–667. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)00995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harker LA, Malpass TW, Branson HE, Hessel EA, 2nd, Slichter SJ. Mechanism of abnormal bleeding in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass: acquired transient platelet dysfunction associated with selective alfa-granule release. Blood. 1980;56:824–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagge L, Lilienberg G, Nyström SO, Tyden H. Coagulation, fibrinolysis and bleeding after open-heart surgery. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;20:151–160. doi: 10.3109/14017438609106494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nezafati P, Shomali A, Kahrom M, Tehrani SO, Dianatkhah M, Nezafati MH. ZipFix versus conventional sternal closure: one-year follow-up. Hear Lung Circ. 2019;28:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song DH, Lohman RF, Renucci JD, Jeevanandam V, Raman J. Primary sternal plating in high-risk patients prevents mediastinitis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tam DY, Nedadur R, Yu M, Yanagawa B, Fremes SE, Friedrich JO. Rigid plate fixation versus wire cerclage for sternotomy after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma R, Puri D, Panigrahi BP, Virdi IS. A modified parasternal wire technique for prevention and treatment of sternal dehiscence. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:210–213. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottio T, Rizzoli G, Vida V, Casarotto D, Gerosa G. Double crisscross sternal wiring and chest wound infections: a prospective randomized study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:1352–1356. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00945-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All of the relevant data is available within the manuscript and its supplements.