Abstract

Maternal undernutrition remains a major public health concern in Rwanda despite significant gains and progress. An integration of nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions was implemented in five districts of Rwanda to improve maternal and child nutrition. The package included nutrition education and counselling, promotion of agricultural productivity, promotion of financial literacy/economic resilience and provision of Water, Hygiene and Sanitation services. However, there is limited evidence about the effect of such interventions in reducing maternal undernutrition. A postintervention quasi‐experimental study was conducted among pregnant women to determine the effect of the integrated intervention on their nutritional status. It was carried out in two intervention districts, namely Kicukiro and Kayonza, and two control districts, namely Gasabo and Gisagara between November 2020 and June 2021. Five hundred and fifty‐two women were recruited for the intervention arm, while 545 were recruited for the control arm. Maternal undernutrition was defined as either having low mid‐upper arm circumference (<23 cm) during delivery or low body mass index (<18.5 kg/m2) in the first trimester or both. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to assess the effect of the integrated interventions. The prevalence of maternal undernutrition was significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the control group (4.7% vs. 18.2%; p < 0.001). After controlling the potential confounders, the risk of maternal undernutrition was 77.0% lower in the intervention group than in the control group [adjusted odds ratio= 0.23; 95% confidence interval = 0.15–0.36; p < 0.001]. Further studies are therefore recommended to establish causation and inform the potential scale‐up of these interventions nationally in Rwanda.

Keywords: integrated intervention package, maternal undernutrition, nutrition‐sensitive, nutrition‐specific, pregnant women, quasi‐experimental

A postintervention quasi‐experimental study was conducted among pregnant women to determine the effect of the integrated intervention on their nutritional status. The results indicated that the integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive intervention package was significantly associated with low maternal undernutrition.

Key messages

Empirical evidence on the effect of integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions on maternal undernutrition is limited as existing studies are mainly directed at the effectiveness of nutritional interventions on improving child nutritional status.

The results indicated that the integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive intervention package was significantly associated with low maternal undernutrition.

This study adds more evidence to the 2008, 2013 and 2021 Lancet Series regarding the proposed effectiveness of integrated nutrition‐sensitive and nutrition‐specific interventions.

Further research should focus on follow‐up randomized controlled trials and the cost‐effectiveness of these integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions.

1. INTRODUCTION

Maternal undernutrition among pregnant women remains a public health concern globally (Black et al., 2013; Salunkhe, 2018) and locally (Williams et al., 2019) due to its unwanted consequences for both women and their babies (Black et al., 2013). The magnitude and burden of maternal undernutrition are unacceptably high in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC) in spite of extensive global economic growth in recent decades (Nana & Zema, 2018; Tang et al., 2016). It is reported that in many sub‐Saharan African and South Asian countries, more than 20% of pregnant women are malnourished (Ravaoarisoa et al., 2018). In Rwanda, undernutrition among pregnant women measured by mid‐upper arm circumference (MUAC) less than 23 cm is 19.8% (Nsereko et al., 2020) and anaemia is estimated at about 24.5% (RDHS, 2020). It is a principal underlying cause of 3.5 million maternal mortalities in LMICs (Black et al., 2013; Loudyi et al., 2016) and various adverse pregnancy outcomes (Acharya et al., 2017; Hasan et al., 2017; Mosha et al., 2018; Victora et al., 2016).

The factors and pathways leading to maternal malnutrition are diverse, complex, and most often interconnected (Dattijo et al., 2016; Gebre & Mulugeta, 2015; Ismail et al., 2017; Obai et al., 2016; Stevens et al., 2012). They are mainly classified as immediate determinants (inadequate food/nutrient and disease), underlying determinants (household food insecurity, unsafe environments and inadequate access/availability to health services) and basic determinants (rooted in poverty and involve interactions between social, demographic and societal conditions) (Black et al., 2013; UNICEF, 1990).

Given the high burden, negative effects and well‐established determinants of maternal undernutrition, there is an urgent need for interventions to reduce it. The Lancet Maternal and Child Nutrition series in 2013 and 2021 identified cost‐effective interventions, including nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions to improve maternal and child nutrition (Bhutta et al., 2013; Keats et al., 2021; Ruel et al., 2013). The Lancet Nutrition Series also reported that nutrition‐specific interventions alone would only reduce malnutrition by 20% if implemented on a large scale (Bhutta et al., 2013), whereas the remaining 80% would be addressed through nutrition‐sensitive interventions. Evidently, a number of studies and reviews on the effect of such interventions to address maternal undernutrition have mostly considered single interventions and showed mixed results, whereby the evidence for such interventions was found to range from modest to highly effective (Carletto et al., 2015; Dangour et al., 2013; Demilew et al., 2020; Gilligan et al., 2014; Gilmore & McAuliffe, 2013; Girard & Olude, 2012; Hambidge & Krebs, 2018; Headey, 2012; Masset et al., 2012; Nielsen et al., 2006; Reinhardt & Fanzo, 2014; World Health Organization [WHO] Reproductive Health Library, 2016)

It has been proposed that integrated or combined nutrition interventions may produce a greater effect in reducing malnutrition (Ruel et al., 2018). For instance, a single sector agriculture programme would sensibly change diets; however, it may not have a significant effect on malnutrition unless mainstreaming it alongside an intervention targeting to affect the other underlying determinants (Bonde, 2016). There is some evidence that economic strengthening is more effective when complemented with other nutrition‐sensitive interventions (Fenn & Yakowenko, 2015). Moreover, the effect of nutrition education and counselling would be greater if delivered with other nutrition‐sensitive interventions, such as nutrition safety nets or promoting economic growth (Girard & Olude, 2012). Most studies have recommended that high quality and further research be conducted on the effect of these combined nutrition interventions (da Silva Lopes et al., 2017; Soltani et al., 2015; Zerfu et al., 2016).

In line with the Lancet series, the Government of Rwanda and its development partners are focusing on the delivery of key evidence‐based interventions to reduce maternal and child malnutrition. For example, the United States Agency for International Development in Rwanda (USAID/Rwanda) implemented evidence‐based nutrition interventions through a programme called Gikuriro (good growth as opposed to stunting) from 2016 to 2020 in five targeted districts. The targeted districts are Kayonza and Ngoma from Eastern Province, Nyabihu from Western Province and Kicukiro and Nyarugenge from Kigali City. These districts were implementing an Integrated Nutrition and Water, Hygiene and Sanitation (WASH) Activities programme. Catholic Relief Service (CRS) and its implementing partners implemented the Gikuriro programme in these five districts in close collaboration with the government structures in these districts. The package of interventions in the programme includes nutrition education and counselling, as a nutrition‐specific intervention as well as to promote increased agricultural productivity, promoting financial literacy/economic resilience and improved WASH services as key nutrition‐sensitive interventions.

Although there is increasing interest in nutrition, little or no attention has been given to generating evidence as to whether combining nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions can lead to greater improvements in maternal malnutrition (Khalid et al., 2019). Even though Gikuriro's evaluations presented some trends to this effect, there are limited scientific comparative studies investigating the effect of integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive intervention packages on maternal undernutrition. The current study aimed at assessing the effect of integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive on maternal nutritional status.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design, setting and participants

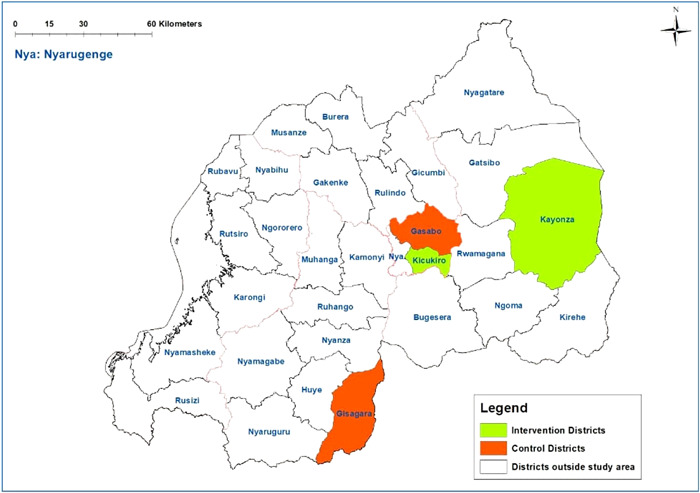

We conducted a postprogramme quasi‐experimental study from November 2020 to June 2021. This design was used to compare maternal undernutrition between the intervention and control groups. The intervention group was drawn from Kayonza District (a rural area) and Kicukiro District (an urban area), two out of the five districts where nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions were implemented under the Gikuriro programme. They were selected based on their high proportion of food insecurity as reported by the Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis (World Food Programme, 2018) and settlement pattern (rural vs. urban). In selecting the control districts, three criteria were used. These include food insecurity (World Food Programme, 2018), no existing nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive intervention package and setting whether rural or urban. After considering all the criteria, Gisagara District (a rural area) and Gasabo District (an urban area) were selected. The selected districts are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area

Participants in this study were pregnant women coming for delivery, and who reside in the selected districts of Rwanda. They were recruited consecutively using the following criteria: (1) being a permanent resident in the study area and aged between 15 and 49 years, (2) having been enroled in the selected nutrition intervention package for at least 1 year before pregnancy (for the intervention group), (3) belonging to wealth categories 1 and 2 and (4) those without any known medical, surgical or obstetric conditions. All public health facilities in the selected districts were included and the distribution of participants was based proportionally on population size in each selected health facility in the respective district.

The sample size was calculated using a two proportion sample size formula (Casagrande et al., 1978), which is:

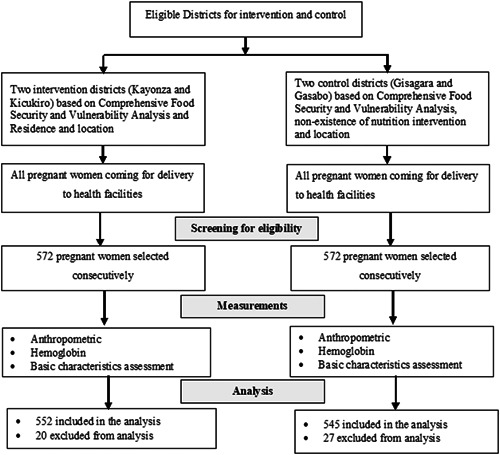

where Ζ 1 − α/2 (95% confidence) = 1.96; Ζ 1 − β (90% power) = 1.64; P 1 = proportion of undernutrition among pregnant women in Rwanda to be 19.8% (Nsereko et al., 2020) in the nonintervention group; P 2 = proportion of undernutrition in the intervention group to be 9.8% (assuming that the intervention would lead to a 10% decrease); design effect = 1.2; effect size = 10; and P = average for the two proportions. After considering all the assumptions, the sample size was 520 for one group. Allowing for nonresponse rate = 10%, the sample size was adjusted upwards to 572. Therefore, the sample size in each group was 572 giving a total sample of 1144 (572 intervention group and 572 control group). A flow chart of participants' recruitment for the intervention and control arms is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Recruitment flow chart

2.2. Description of the intervention

The integrated nutrition intervention package refers to one component of nutrition‐specific intervention, which is nutrition education and counselling and three nutrition‐sensitive components, which are promotion of agricultural productivity, promotion of financial literacy and economic resilience and improved access to WASH services. The interventions took place between September 2016 and July 2020. The intervention was funded by USAID and implemented by CRS in partnership with the Government of Rwanda, Netherlands Development Organization and other Rwandan Civil‐Society Organizations.

A detailed description of these interventions is provided in Additional File 1. The main objective of the intervention was to improve the nutritional status of women of reproductive age and children less than 5 years. Nutrition education and counselling were promoted through a variety of behaviour change activities, including Village Nutrition Schools, community health clubs, growth monitoring and promotion by trained Community Health Workers. Regarding agriculture, the main activities of the intervention were enhancing agricultural productivity through Farmer Field Schools established in each village, promoting Bio Intensive Agriculture Techniques and distribution of seeds and livestock. The programme also enhanced the Saving and Internal Lending Communities Groups approach as a way of promoting financial literacy and economic growth to tackle financial problems that prevent women and children from attaining better nutritional outcomes. In addition, the intervention extended to roll‐out WASH activities through the Community‐Based Environmental Health Promotion Programme approach adopted by the Government of Rwanda and fostering the integration of WASH and nutrition to improve sanitation, latrines and handwashing facilities.

2.3. Data collection and measures

Data collectors were trained on the objectives, the relevance of the study, confidentiality of information, respondent's rights, informed consent, techniques of the face‐to‐face interviews and anthropometric measurements. The interviews were conducted in a private place to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of the participants. Validation and verification of data were done at the end of each day of data collection. Supervisors checked completed questionnaires or checklists daily and signed off each time they supervised the enumerators.

The data were collected using a structured questionnaire adopted from other similar studies (Ghosh et al., 2019). However, it was modified to suit the Rwandan context after pretesting it in a district outside the study area. The main component of the questionnaire included maternal sociodemographic characteristics, socioeconomic characteristics and lifestyle factors, as well as obstetric factors.

Maternal nutritional status was measured using two anthropometric measurements: MUAC just before delivery and body mass index (BMI) in the first trimester. A flexible nonelastic tape was used to measure the MUAC. It was measured midway between the tip of the shoulder and the tip of the elbow of the less functional arm hanging freely by the woman's side. In addition, antenatal care records were reviewed to retrieve weight and height during the first trimester to estimate the BMI. The weight and height had been measured according to Rwandan Ministry of Health guidelines using the devices available in the health facilities. A woman who had low MUAC (<23 cm) during delivery or low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) in the first trimester or both were categorized as having maternal undernutrition.

Moreover, haemoglobin (Hb) concentration to assess for anaemia was measured using a portable HEMOCUE B‐Hb photometer using one drop of capillary blood obtained via a finger prick by trained midwives and according to Rwandan Ministry of Health guidelines. Based on WHO classification (1989), Hb reading of ≥11 g/dl was considered normal and <11 g/dl was anaemic. The severity of anaemia was grouped into three levels: mild (Hb readings 9–10.9 g/dl), moderate (Hb readings 7–8.9 g/dl) and severe anaemia (Hb < 7 g/dl).

2.4. Data analysis

Descriptive analysis, including counts, proportions and averages, was used to assess the distribution of the attributes. To assess the balance of the explanatory variables and nutritional status between the intervention and control groups, the χ 2 test (comparing proportion) and independent t test (comparing means) were performed. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to identify the association between the integrated nutrition intervention and maternal undernutrition. All potential confounders with a p value <0.1 during the comparison between intervention and control groups were considered in a multiple logistic regression using a ‘backward conditional' selection procedure. The potential confounders included were the main source of fuel/energy for lighting, having household items, alcohol consumption, smoking, exposure to secondary smoke and HIV status. Model adequacy was checked using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness‐of‐fit test (p = 0.127), which indicates that the fitted model was adequate. Results were statistically significant at p value <0.05. The data were analysed with help of Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 25.0 IBM New York.

2.5. Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct the study was sought and obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Rwanda College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Authorization to go to the field was also granted by the Ministry of Health, Rwanda. Written informed consent was sought and obtained from each participant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the women

A total of 1097 women coming for delivery were included in the analysis giving a response rate of 96.5% (552 out of 572) for the intervention group and 95.3% (545 out of 572) for the control group. Table 1 compares the basic demographic characteristics of the women in the intervention and control groups. There was no significant difference between the intervention and control groups.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of women

| Variables | Total, % (n) | Intervention, % (n) | Control, % (n) | χ 2value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 15–19 | 6.3 (69) | 6.9 (38) | 5.7 (31) | 4.66 | 0.459 |

| 20–24 | 26.2 (287) | 25.9 (143) | 26.4 (144) | ||

| 25–29 | 27.3 (302) | 28.6 (158) | 26.4 (144) | ||

| 30–34 | 21.3 (234) | 22.1 (122) | 20.6 (112) | ||

| 35–39 | 14.2 (156) | 12.9 (71) | 15.6 (85) | ||

| 40+ | 4.5 (49) | 3.6 (20) | 5.3 (29) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 46.1 (506) | 48.8 (267) | 43.9 (239) | 3.8 | 0.283 |

| Cohabitating | 42.4 (465) | 41.7 (230) | 43.1 (235) | ||

| Single | 10.4 (114) | 8.9 (49) | 11.9 (65) | ||

| Divorced or separated | 1.1 (12) | 1.1 (6) | 1.1 (6) | ||

| Religion | |||||

| Christian | 95.4 (1046) | 94.7 (523) | 96.0 (523) | 1.15 | 0.563 |

| Muslim | 3.7 (41) | 4.3 (24) | 3.1 (17) | ||

| Others | 0.9 (10) | 0.9 (5) | 0.9 (5) | ||

| Level of education | |||||

| None | 11.8 (129) | 11.4 (63) | 12.1 (66) | 4.25 | 0.374 |

| Primary | 62.6 (687) | 62.9 (347) | 62.4 (340) | ||

| Secondary | 22.6 (248) | 23.2 (128) | 22.0 (120) | ||

| Vocational | 1.2 (13) | 1.4 (8) | 0.9 (5) | ||

| Higher education | 1.8 (20) | 1.1 (6) | 2.6 (14) | ||

| Spouse's/partner's completed level of educationa | |||||

| None | 9.5 (92) | 8.9 (44) | 10.1 (48) | 2.5 | 0.777 |

| Primary | 56.1 (545) | 56.1 (279) | 56.1 (266) | ||

| Secondary | 25.1 (245) | 26.0 (129) | 24.5 (116) | ||

| Vocational | 3.7 (36) | 3.2 (16) | 4.2 (20) | ||

| Higher education | 2.8 (27) | 2.6 (13) | 3.0 (14) | ||

| Don't know | 2.7 (26) | 3.2 (16) | 2.1 (10) | ||

| Number of household members [mean, SD] | 4.8 [1.76] | 4.45 [1.83] | 4.52 [1.68] | −0.68 | 0.499b |

Total response was 971.

Independent t test was used to compare the total number of household members.

3.2. Socioeconomic factors of the women

The distribution of the socioeconomic characteristics is summarized in Table 2. When comparing the proportions between the intervention and control groups, there was no significant discrepancy. Although the proportions of those having electricity and household items were higher among the intervention group, they were not statistically significant. Similarly, even though owning livestock was higher among the control group, this difference was not found to be statistically significant either.

Table 2.

Socioeconomic factors of women

| Variables | Total, % (n) | Intervention, % (n) | Control, % (n) | χ 2value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | |||||

| Farming/agriculture | 41.8 (459) | 39.5 (218) | 44.2 (241) | 4.59 | 0.469 |

| Housewife/unemployed | 19.0 (208) | 19.7 (109) | 18.2 (99) | ||

| Salaried employee | 3.4 (37) | 3.6 (20) | 3.1 (17) | ||

| Self‐employed | 10.8 (118) | 12.3 (68) | 9.2 (50) | ||

| Casual wage | 23.4 (257) | 23.2 (128) | 23.7 (129) | ||

| Student | 1.6 (18) | 1.6 (9) | 1.7 (9) | ||

| Spouse's/partner's employment statusa | |||||

| Farming/agriculture | 40.6 (394) | 38.8 (193) | 42.4 (201) | 9.25 | 0.100 |

| Salaried employee | 8.5 (83) | 8.9 (44) | 8.2 (39) | ||

| Self‐employed | 16.8 (163) | 19.7 (98) | 13.7 (65) | ||

| Casual wage | 29.6 (287) | 28.6 (142) | 30.6 (145) | ||

| Unemployed | 3.8 (37) | 3.0 (15) | 4.6 (22) | ||

| Student | 0.7 (7) | 1.0 (5) | 0.4 (2) | ||

| Ownership of a house | |||||

| Self | 46.9 (514) | 45.5 (251) | 48.3 (263) | 4.00 | 0.165 |

| Rental | 49.1 (539) | 49.5 (273) | 48.8 (266) | ||

| Others | 4.0 (44) | 5.1 (28) | 2.9 (16) | ||

| Most common cooking fuel | |||||

| Wood or charcoal | 96.4 (1057) | 95.3 (526) | 97.4 (531) | 3.94 | 0.140 |

| Gas or biogas | 2.4 (26) | 2.9 (16) | 1.8 (10) | ||

| Electricity | 1.3 (14) | 1.8 (10) | 0.7 (4) | ||

| Main source of fuel or energy for lighting | |||||

| Electricity | 65.2 (715) | 68.3 (377) | 62.0 (338) | 7.42 | 0.060 |

| Solar | 9.4 (103) | 9.1 (50) | 9.7 (53) | ||

| Gas | 1.3 (14) | 1.6 (9) | 0.9 (5) | ||

| Others (torch) | 24.2 (265) | 21.0 (116) | 27.3 (149) | ||

| Having household itemsb | |||||

| Yes | 83.3 (914) | 85.3 (471) | 81.3 (443) | 3.22 | 0.073 |

| No | 16.7 (183) | 14.7 (81) | 18.7 (102) | ||

| Owning agricultural land | |||||

| Yes | 41.7 (457) | 43.3 (239) | 40.0 (218) | 1.23 | 0.268 |

| No | 58.3 (640) | 56.7 (313) | 60.0 (327) | ||

Total response = 971.

Household items include radio, TV, telephone—fixed line, mobile phone, car and motorcycle.

3.3. Lifestyle and obstetric factors

The results revealed that 14.7%, 2.6% and 11.7% of the women took alcohol, smoked and were exposed to secondary smoke, respectively. These lifestyle factors were significantly different between the intervention and control groups, where the percentages were more among controls than among the intervention group. Regarding obstetric factors, 94.4% visited antenatal care services; however, there was no statistically significant variation between the two groups. The prevalence of HIV infection was significantly more among the intervention group compared with the control group (5.8% vs. 3.1%; p = 0.032) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Lifestyle and obstetric factors

| Variables | Total, % (on) | Intervention, % (n) | Control, % (n) | χ 2value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking alcohol during pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 14.7 (161) | 12.1 (67) | 17.2 (94) | 5.719 | 0.017 |

| No | 85.3 (936) | 87.9 (485) | 82.8 (451) | ||

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 2.6 (29) | 1.1 (6) | 4.2 (23) | 10.461 | 0.001 |

| No | 97.4 (1068) | 98.9 (546) | 522 (95.8) | ||

| Partner smoking | |||||

| Yes | 11.7 (128) | 7.6 (42) | 15.8 (86) | 17.765 | <0.001 |

| No | 88.3 (969) | 92.4 (510) | 84.2 (459) | ||

| ANC visit | |||||

| Yes | 94.4 (1036) | 94.4 (521) | 94.5 (515) | 0.006 | 0.936 |

| No | 5.6 (61) | 5.6 (31) | 5.5 (30) | ||

| ANC frequency | |||||

| 1 | 20.0 (207) | 22.6 (118) | 17.3 (89) | 4.866 | 0.182 |

| 2 | 16.9 (175) | 15.9 (83) | 17.9 (92) | ||

| 3 | 29.2 (303) | 28.8 (150) | 29.7 (153) | ||

| 4+ | 33.9 (351) | 32.6 (170) | 35.1 (181) | ||

| HIV status | |||||

| Negative | 95.5 (1048) | 94.2 (520) | 96.9 (528) | 4.608 | 0.032 |

| Positive | 4.5 (49) | 5.8 (32) | 3.1 (17) | ||

Note: Bolded p value indicate significant association at p < 0.05.

Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

3.4. Nutritional status of the women

The overall prevalence of anaemia was 17.0% with a significant difference (p < 0.001) observed between the intervention (10.5%) and control groups (23.7%). The mean Hb level was 12.38 for both groups and it was significantly (p < 0.001) more among the intervention group (12.65 g/dl) compared with the control group (12.1 g/dl). The severity of anaemia was assessed, and the proportion of moderate anaemia was high in the control group while mild anaemia was more among the intervention group (p = 0.014).

Similarly, the average MUAC was significantly higher among the intervention group (26.06 cm) compared with 24.87 cm in the control group (p < 0.001). The proportion of MAUC < 23 cm was also significantly higher (p < 0.001) in control group (14.5%) than in intervention group (3.4%). Similarly, the proportion of those with BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 in the first trimester was significantly lower (p = 0.010) among women in the intervention group (1.8%) than among those in the control group (5.5%). The average weight in the first and third trimesters was also significantly higher among the participants in the intervention group (p < 0.001). Although the average weight gain between the first and third trimesters was higher among the intervention group, there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.119) between the two groups.

After considering MUAC and BMI, the overall prevalence of maternal undernutrition was 11.4% and this was significantly more (p < 0.001) among controls (18.2%) compared with the intervention group (4.7%). (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nutritional status of the women

| Variables | Total, % (n) | Intervention, % (n) | Control, % (n) | χ 2values | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaemia status | |||||

| Anaemic (Hb < 11 g/dl) | 17.0 (187) | 10.5 (58) | 23.7 (129) | 33.6 | <0.001 |

| Normal (Hb ≥ 11 g/dl) | 83.0 (910) | 89.5 (494) | 76.3 (416) | ||

| Hb concentration [mean, SD] | 12.38 [1.39] | 12.65 [1.24] | 12.10 [1.48] | 6.71 | <0.001 a |

| Severity of anaemia (n = 187) | |||||

| Mild (Hb = 9–10.9 g/dl) | 90.4 (169) | 98.3 (57) | 86.8 (112) | 6.03 | 0.014 |

| Moderate (Hb = 7–8.9 g/dl) | 9.6 (18) | 1.7 (1) | 13.2 (17) | ||

| Acute wasting status | |||||

| Wasting (MUAC < 23 cm) | 8.9 (98) | 3.4 (19) | 14.5 (79) | 41.18 | <0.001 |

| Normal (MUAC ≥ 23 cm) | 91.1 (999) | 96.6 (533) | 85.5 (466) | ||

| MUAC [mean, SD] | 25.47 [2.52] | 26.06 [2.46] | 24.87 [2.45] | 8.05 | <0.001 a |

| Underweight status in the first trimesterb | |||||

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) | 3.8 (32) | 1.8 (7) | 5.5 (25) | 9.12 | 0.01 |

| Normal (BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m2) | 76.3 (646) | 76.2 (297) | 76.4 (349) | ||

| Overweight/obese (BMI > 25.0 kg/m2) | 20.0 (169) | 22.1 (86) | 18.2 (83) | ||

| BMI [mean, SD] | 23.06 [2.89] | 23.46 [2.97] | 22.73 [2.78] | 3.71 | <0.001 a |

| Estimated average weight gain | |||||

| Estimated average weight in the first trimester [SD]b | 60.09 [8.83] | 61.86 [9.14] | 58.57 [7.67] | 5.64 | <0.001 a |

| Estimated average weight in the third trimester [SD]c | 64.86 [8.78] | 66.74 [9.52] | 63.26 [7.76] | 5.86 | <0.001 a |

| Estimated average weight gain between third and first trimester [SD]d | 4.76 [2.02] | 4.88 [2.17] | 4.66 [1.88] | 1.56 | 0.119a |

| Overall maternal undernutrition | |||||

| Undernourishede | 11.4 (125) | 4.7 (26) | 18.2 (99) | 49.17 | <0.001 |

| Normal | 88.6 (972) | 95.3 (526) | 81.8 (446) | ||

Note: Bolded p value indicate significant association at p < 0.05.

Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; BMI, body mass index; Hb, haemoglobin; MUAC, mid‐upper arm circumference; SD, standard deviation.

Mean was compared using independent t test.

Overall total = 847; intervention = 390; control = 457.

Overall total = 849; intervention = 389; control = 460.

Overall total = 843; intervention = 389; control = 454; the weight gain is an estimate between any time within third trimester and first trimester, which are retrieved from ANC records.

Maternal undernutrition was assessed using low MUAC (<23 cm) during delivery or low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) in first trimester or both.

3.5. Effect of the integrated nutrition intervention on maternal undernutrition

The integrated package of nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions was identified as an independent factor associated with maternal undernutrition as presented in Table 5. Maternal undernutrition was defined as low MUAC (<23 cm) during delivery or low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) in the first trimester or both. After controlling the potential confounders using multivariable logistic regression, maternal undernutrition was 77% times less likely to occur among pregnant women in the intervention group compared with those in the control group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.23; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.15–0.36; p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Effect of the intervention on maternal malnutrition

| Group | Maternal undernutritiona, % (95% CI) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Control | 18.2 (15.02–21.66) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Intervention | 4.7 (3.10–6.83) | 0.22 (0.14–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.15–0.36) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Maternal undernutrition was defined as low MUAC (<23 cm) during delivery or low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) in the first trimester or both.

The odds ratio is adjusted with fuel/energy for lighting, having household items, alcohol consumption, smoking, exposure to secondary smoke and HIV status.

4. DISCUSSION

Despite the primary limitation of this study, which was the lack of baseline data on maternal nutritional status, it however contributes to the scarce literature on the effect of combined nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive intervention programmes in reducing maternal undernutrition. Constructing on Lancet Maternal and Child Nutrition Series proposed in 2013 (Bhutta et al., 2013), community‐based interventions focusing on nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions can prevent maternal undernutrition. Previously all studies conducted were on the individual interventions and these showed varying strength of evidence from weak to moderate. Moreover, only some nutritional programmes have shown their effect on the reduction of undernutrition (Ruel et al., 2013). Combined interventions may have more promising results than single interventions. However, there is a lack of robust evidence for assessing the effect of combined nutrition‐sensitive and nutrition‐specific interventions. This study, to our knowledge, is the first quasi‐experimental comparative study on the effect of combined nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions on maternal nutritional status.

According to this study, it was found that integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions were associated with lower maternal undernutrition during pregnancy. This is parallel with the current literature and evidence that supports the notion that integrated nutrition‐sensitive and nutrition‐specific intervention programmes produce a superior effect on nutritional outcomes compared with either nutrition‐sensitive or nutrition‐specific interventions alone (Abdullahi et al., 2021). It also supports the 2008, 2013 and 2021 Lancet Series regarding the proposed impact of evidence‐based interventions in reducing maternal undernutrition (Bhutta et al., 2008, 2013; Keats et al., 2021).

However, as aforementioned, it is quite difficult to compare and contrast other studies with our findings because of the differences in the components used in the intervention package. This study used combined interventions, whereas most of the past studies conducted used individual interventions, such as only agriculture sensitive intervention or economic promotion or nutrition education or WASH and sometimes these interventions were with or without nutrition education. In addition, these single interventions showed varying evidence from none to moderate or high (Dangour et al., 2013; Demilew et al., 2020; Headey, 2012; Kadiyala et al., 2021; Michaux et al., 2019; Olney et al., 2016; Osei et al., 2017; Ruel et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2021).

One of the main reasons for single interventions producing a weak impact in reducing undernutrition is that the underlying determinants of undernutrition are not adequately addressed. It was indicated that, for example, promoting agricultural productivity/intervention and integrated multiple interventions can address both immediate and underlying determinants of undernutrition (Ruel et al., 2018); these multiple sectors may include nutrition education and counselling, social safety nets and WASH. Another reason could be the short period of implementing intervention programmes, which may fail to address the underlying causes of undernutrition (Ruel et al., 2018).

However, our study addressed these gaps. The nutrition‐specific intervention of nutritional education and counselling led to improved dietary diversity, thus addressing the immediate causes of maternal undernutrition. The nutrition‐sensitive intervention in the package, which included promotion of agricultural productivity, promotion of financial literacy and economic growth and improved access to WASH activities, led to improved food security and better hygiene/sanitation, thus addressing the underlying causes of maternal undernutrition.

Therefore, the possible explanation for the greater reduction of undernutrition among pregnant women in this study could be the combined interventions that worked in synergy. Further, there is evidence that gender‐sensitive interventions have a positive impact on empowering women (Kumar et al., 2018). This empowerment may promote decision making, gender equality, social capital, communication with partners and access to resources, which further improves the nutritional status of women. Another plausible explanation of the observed end‐line differences could be that the women might have been nutritionally different at baseline and those differences could have persisted throughout pregnancy.

Though nutrition‐specific interventions can have a great impact on minimizing undernutrition, alone they may not eradicate malnutrition. However, if it is combined with nutrition‐sensitive interventions, there could be a huge impact on the elimination of undernutrition (Abdullahi et al., 2021). The nutrition‐sensitive interventions, which address the underlying causes of malnutrition are believed to reduce malnutrition by 80%, while the direct malnutrition interventions address only 20% even if scaled up to 90% coverage rates (IFPRI, 2016). Moreover, nutrition‐sensitive interventions hold great promise for improving nutritional outcomes and enhancing the coverage and effectiveness of nutrition‐specific interventions (Ruel et al., 2013). Hence, the combined package with both nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions has more promising results than single interventions.

The strengths of the present study include the use of robust evaluation design (well‐designed post quasi‐experiment), well‐powered sample size and long duration impact of programme evaluation (5 years). However, attention should be given to some limitations. One of the limitations of our study is the use of only end‐line postprogramme evaluation, which limits the appreciation of the trend of nutritional indicators during pregnancy. Another limitation was the lack of randomization to minimize bias. However, including a control group and recruiting those women in the intervention before they became pregnant could have reduced bias. Furthermore, when checked, the basic characteristics of the two groups were similar, hence the possibility that the observed differences in outcomes could be due to the combined intervention.

5. CONCLUSION

Our study showed that the integrated nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions, including nutrition counselling and education, promotion of financial literacy/economic resilience, promotion of agricultural interventions.productivity and improved access to WASH activities can reduce maternal malnutrition, such as anaemia and undernutrition. There is therefore a good case for possible scale‐up of the combined nutrition‐sensitive and nutrition‐specific interventions country‐wide to address undernutrition among pregnant women. Of note, however, is that our study only considered end‐line evaluation of nutritional status and therefore recommends studies that consider both baseline and end‐line assessment and randomization to further inform the scale‐up of the interventions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Michael Habtu: Conceptualized, designed and carried out the research, as well as analysed and wrote the manuscript. Cyprien Munyanshongore, Maryse Umugwaneza, Alemayehu Gebremariam Agena and Monica Monchama: Discussed and provided critical comments on the paper. All authors have read and approved the manuscript for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Rwanda Ministry of Health for allowing us to conduct the study. We also thank all research assistants and respondents for their time and data collection.

Habtu, M. , Agena, A. G. , Umugwaneza, M. , Monchama, M. , & Munyanshongore, C. (2022). Effect of integrated nutrition‐sensitive and nutrition‐specific intervention package on maternal malnutrition among pregnant women in Rwanda. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18, e13367. 10.1111/mcn.13367

[Correction added on 20 may 2022, after first online publication: Corrections added in corresponding address, on page 7 and table 4.]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The study data sets are available from the corresponding author on request.

REFERENCES

- Abdullahi, L. H. , Rithaa, G. K. , Muthomi, B. , Kyallo, F. , Ngina, C. , Hassan, M. A. , & Farah, M. A. (2021). Best practices and opportunities for integrating nutrition specific into nutrition sensitive interventions in fragile contexts: A systematic review. BMC Nutrition, 7(1), 46. 10.1186/s40795-021-00443-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, S. R. , Bhatta, J. , & Timilsina, D. P. (2017). Factors associated with nutritional status of women of reproductive age group in rural, Nepal. Asian Pacific Journal of Health Sciences, 4(4), 19–24. 10.21276/apjhs.2017.4.4.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, Z. A. , Ahmed, T. , Black, R. E. , Cousens, S. , Dewey, K. , Giugliani, E. , Haider, B. A. , Kirkwood, B. , Morris, S. S. , & Sachdev, H. P. S. (2008). What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. The Lancet, 371(9610), 417–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, Z. A. , Das, J. K. , Rizvi, A. , Gaffey, M. F. , Walker, N. , Horton, S. , Webb, P. , Lartey, A. , & Black, R. E. , Lancet Nutrition Interventions Review Group, the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group . (2013). Evidence‐based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: What can be done and at what cost. Lancet (London, England), 382(9890), 452–477. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60996-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R. E. , Victora, C. G. , Walker, S. P. , Bhutta, Z. A. , Christian, P. , de Onis, M. , Ezzati, M. , Grantham‐McGregor, S. , Katz, J. , Martorell, R. , & Uauy, R. , Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group . (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low‐income and middle‐income countries. Lancet (London, England), 382(9890), 427–451. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde, D. (2016). Impact of agronomy and livestock interventions on women's and child dietary diversity in Mali. Field Exchange, 51, 132‐133. [Google Scholar]

- Carletto, G. , Ruel, M. , Winters, P. , & Zezza, A. (2015). Farm‐level pathways to improved nutritional status: Introduction to the special issue. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(8), 945–957. 10.1080/00220388.2015.1018908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, J. T. , Pike, M. C. , & Smith, P. G. (1978). An Improved approximate formula for calculating sample sizes for comparing two binomial distributions. Biometrics, 34(3), 483. 10.2307/2530613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Lopes, K. , Ota, E. , Shakya, P. , Dagvadorj, A. , Balogun, O. O. , Peña‐Rosas, J. P. , De‐Regil, L. M. , & Mori, R. (2017). Effects of nutrition interventions during pregnancy on low birth weight: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Global Health, 2(3), e000389. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangour, A. D. , Watson, L. , Cumming, O. , Boisson, S. , Che, Y. , Velleman, Y. , Cavill, S. , Allen, E. , & Uauy, R. (2013). Interventions to improve water quality and supply, sanitation and hygiene practices, and their effects on the nutritional status of children. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8, CD009382. 10.1002/14651858.CD009382.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dattijo, L. , Daru, P. , & Umar, N. (2016). Anaemia in pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors in Azare, North‐East Nigeria. International Journal of Tropical Disease & Health, 11(1), 1–9. 10.9734/IJTDH/2016/20791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demilew, Y. M. , Alene, G. D. , & Belachew, T. (2020). Effect of guided counseling on nutritional status of pregnant women in West Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: A cluster‐randomized controlled trial. Nutrition Journal, 19(1), 38. 10.1186/s12937-020-00536-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn, B. , & Yakowenko, E. (2015). Literature review on impact of cash transfers on nutritional outcomes. Field Exchange, 49, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Gebre, A. , & Mulugeta, A. (2015). Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in North Western Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2015, 165430. 10.1155/2015/165430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S. , Spielman, K. , Kershaw, M. , Ayele, K. , Kidane, Y. , Zillmer, K. , Wentworth, L. , Pokharel, A. , Griffiths, J. K. , & Belachew, T. (2019). Nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive factors associated with mid‐upper arm circumference as a measure of nutritional status in pregnant Ethiopian women: Implications for programming in the first 1000 days. PLoS One, 14(3), e0214358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, D. , Hidrobo, M. , Hoddinott, J. , Roy, S. , & Schwab, B. (2014). Much ado about modalities: Multicountry experiments on the effects of cash and food transfers on consumption patterns. Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. 10.22004/ag.econ.171159 [DOI]

- Gilmore, B. , & McAuliffe, E. (2013). Effectiveness of community health workers delivering preventive interventions for maternal and child health in low‐and middle‐income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard, A. W. , & Olude, O. (2012). Nutrition education and counselling provided during pregnancy: Effects on maternal, neonatal and child health outcomes. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 26, 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambidge, K. M. , & Krebs, N. F. (2018). Strategies for optimizing maternal nutrition to promote infant development. Reproductive health, 15(1), 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M. , Sutradhar, I. , Shahabuddin, A. S. M. , & Sarker, M. (2017). Double burden of malnutrition among Bangladeshi women: A literature review. Cureus, 9, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headey, D. (2012). Turning economic growth into nutrition‐sensitive growth. In Fan S., & Pandya‐Lorch R. (Eds.), Reshaping agriculture for nutrition and health (Ch. 5, p. 39). IFPRI. [Google Scholar]

- IFPRI . (2016). Global nutrition report 2016: From promise to impact: Ending malnutrition by 2030. 10.2499/9780896295841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, I. M. , Kahkashan, A. , Antony, A. , & Sobhith, V. K. (2017). Role of socio‐demographic and cultural factors on anemia in a tribal population of North Kerala. India. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 3(5), 1183–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Kadiyala, S. , Harris‐Fry, H. , Pradhan, R. , Mohanty, S. , Padhan, S. , Rath, S. , James, P. , Fivian, E. , Koniz‐Booher, P. , & Nair, N. (2021). Effect of nutrition‐sensitive agriculture interventions with participatory videos and women's group meetings on maternal and child nutritional outcomes in rural Odisha, India (UPAVAN trial): A four‐arm, observer‐blind, cluster‐randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(5), e263–e276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, H. , Gill, S. , & Fox, A. M. (2019). Global aid for nutrition‐specific and nutrition‐sensitive interventions and proportion of stunted children across low‐and middle‐income countries: Does aid matter? Health Policy and Planning, 34(Suppl_2), ii18–ii27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keats, E. C. , Das, J. K. , Salam, R. A. , Lassi, Z. S. , Imdad, A. , Black, R. E. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2021). Effective interventions to address maternal and child malnutrition: An update of the evidence. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 5(5), 367–384. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30274-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. , Nguyen, P. H. , Harris, J. , Harvey, D. , Rawat, R. , & Ruel, M. T. (2018). What it takes: Evidence from a nutrition‐and gender‐sensitive agriculture intervention in rural Zambia. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 10(3), 341–372. [Google Scholar]

- Loudyi, F. M. , Kassouati, J. , Kabiri, M. , Chahid, N. , Kharbach, A. , Aguenaou, H. , & Barkat, A. (2016). Vitamin D status in Moroccan pregnant women and newborns: Reports of 102 cases. The Pan African Medical Journal, 24, 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masset, E. , Haddad, L. , Cornelius, A. , & Isaza‐Castro, J. (2012). Effectiveness of agricultural interventions that aim to improve nutritional status of children: Systematic review. BMJ, 344, d8222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosha, D. , Canavan, C. R. , Bellows, A. L. , Blakstad, M. M. , Noor, R. A. , Masanja, H. , Kinabo, J. , & Fawzi, W. (2018). The impact of integrated nutrition‐sensitive interventions on nutrition and health of children and women in rural Tanzania: Study protocol for a cluster‐randomized controlled trial. BMC Nutrition, 4(1), 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaux, K. D. , Hou, K. , Karakochuk, C. D. , Whitfield, K. C. , Ly, S. , Verbowski, V. , Stormer, A. , Porter, K. , Li, K. H. , Houghton, L. A. , Lynd, L. D. , Talukder, A. , McLean, J. , & Green, T. J. (2019). Effect of enhanced homestead food production on anaemia among Cambodian women and children: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(Suppl 3):e12757. 10.1111/mcn.12757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nana, A. , & Zema, T. (2018). Dietary practices and associated factors during pregnancy in northwestern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. N. , Gittelsohn, J. , Anliker, J. , & O'Brien, K. (2006). Interventions to improve diet and weight gain among pregnant adolescents and recommendations for future research. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 106(11), 1825–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsereko, E. , Uwase, A. , Mukabutera, A. , Muvunyi, C. M. , Rulisa, S. , Ntirushwa, D. , Moreland, P. , Corwin, E. J. , Santos, N. , & Nzayirambaho, M. (2020). Maternal genitourinary infections and poor nutritional status increase risk of preterm birth in Gasabo District, Rwanda: A prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obai, G. , Odongo, P. , & Wanyama, R. (2016). Prevalence of anaemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Gulu and Hoima Regional Hospitals in Uganda: A cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney, D. K. , Bliznashka, L. , Pedehombga, A. , Dillon, A. , Ruel, M. T. , & Heckert, J. (2016). A 2‐year integrated agriculture and nutrition program targeted to mothers of young children in Burkina Faso Reduces underweight among mothers and increases their empowerment: A cluster‐randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Nutrition, 146(5), 1109–1117. 10.3945/jn.115.224261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei, A. , Pandey, P. , Nielsen, J. , Pries, A. , Spiro, D. , Davis, D. , Quinn, V. , & Haselow, N. (2017). Combining home garden, poultry, and nutrition education program targeted to families with young children improved anemia among children and anemia and underweight among nonpregnant women in Nepal. Food and nutrition bulletin, 38(1), 49–64. 10.1177/0379572116676427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravaoarisoa, L. , Randriamanantsaina, L. , Rakotonirina, J. , de Dieu Marie Rakotomanga, J. , Donnen, P. , & Dramaix, M. W. (2018). Socioeconomic determinants of malnutrition among mothers in the Amoron'i Mania region of Madagascar: A cross‐sectional study. BMC Nutrition, 4(1), 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RDHS . (2020). National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], and ICF. 2020. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2019‐20 Key Indicators Report. NISR and ICF. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, K. , & Fanzo, J. (2014). Addressing chronic malnutrition through multi‐sectoral, sustainable approaches: A review of the causes and consequences. Frontiers in Nutrition, 1, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel, M. T. , & Alderman, H. , Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group . (2013). Nutrition‐sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? The Lancet, 382(9891), 536–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel, M. T. , Quisumbing, A. R. , & Balagamwala, M. (2018). Nutrition‐sensitive agriculture: What have we learned so far? Global Food Security, 17, 128–153. 10.1016/j.gfs.2018.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salunkhe, A. H. , Pratinidhi, S. , Kakade, S. V. , Salunkhe, J. A. , Mohite, V. R. , & Bhosale, T. (2018). Nutritional status of mother and gestational age. Online Journal of Health and Allied Sciences, 16(4), Article 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, I. K. , Di Prima, S. , Essink, D. , & Broerse, J. E. W. (2021). Nutrition‐sensitive agriculture: A systematic review of impact pathways to nutrition outcomes. Advances in Nutrition, 12(1), 251–275. 10.1093/advances/nmaa103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, H. , Duxbury, A. M. S. , Rundle, R. , & Chan, L.‐N. (2015). A systematic review of the effects of dietary interventions on neonatal outcomes in adolescent pregnancy. Evidence Based Midwifery, 13(1), 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G. A. , Finucane, M. M. , Paciorek, C. J. , Flaxman, S. R. , White, R. A. , Donner, A. J. , & Ezzati, M. , Nutrition Impact Model Study Group . (2012). Trends in mild, moderate, and severe stunting and underweight, and progress towards MDG 1 in 141 developing countries: A systematic analysis of population representative data. The Lancet, 380(9844), 824–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, A. M. , Chung, M. , Dong, K. , Terrin, N. , Edmonds, A. , Assefa, N. , & Maalouf‐Manasseh, Z. (2016). Determining a global mid‐upper arm circumference cutoff to assess malnutrition in pregnant women. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . (1990). Strategy for improved nutrition of children and women in developing countries. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Requejo, J. H. , Barros, A. J. , Berman, P. , Bhutta, Z. , Boerma, T. , Chopra, M. , De Francisco, A. , Daelmans, B. , & Hazel, E. (2016). Countdown to 2015: A decade of tracking progress for maternal, newborn, and child survival. The Lancet, 387(10032), 2049–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Reproductive Health Library . (2016). WHO recommendation on nutrition education on energy and protein intake during pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P. A. , Schnefke, C. H. , Flax, V. L. , Nyirampeta, S. , Stobaugh, H. , Routte, J. , Musanabaganwa, C. , Ndayisaba, G. , Sayinzoga, F. , & Muth, M. K. (2019). Using trials of improved practices to identify practices to address the double burden of malnutrition among Rwandan children. Public Health Nutrition, 22(17), 3175–3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Food Programme . (2018). Comprehensive food security and vulnerability analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Zerfu, T. A. , Umeta, M. , & Baye, K. (2016). Dietary diversity during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of maternal anemia, preterm delivery, and low birth weight in a prospective cohort study in rural Ethiopia. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(6), 1482–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The study data sets are available from the corresponding author on request.