Summary

The post-menopausal state in women is associated with increased cancer incidence, the reasons for which remain obscure. Curiously, increased circulating levels of beta-hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) (a hormonal subunit linked with tumors of several lineages) are also often observed post-menopause. This study describes a previously unidentified interplay between beta-hCG and progesterone in tumorigenesis. Progesterone mediated apoptosis in beta-hCG responsive tumor cells via non-nuclear receptors. The transgenic expression of beta-hCG, particularly in the absence of the ovaries (a mimic of the post-menopausal state) constituted a potent pro-tumorigenic signal. Significantly, the administration of progesterone had significant anti-tumor effects. RNA-seq profiling identified molecular signatures associated with these processes. TCGA analysis revealed correlates between the expression of several newly identified genes and poor prognosis in post-menopausal patients of lung adenocarcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, and glioblastoma. Specifically in these women, the detection of intra-tumoral/extra-tumoral beta-hCG may serve as a useful prognostic indicator, and treatment with progesterone on its detection may prove beneficial.

Subject areas: Cancer, Cell biology, Physiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Beta-hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) is linked with poor survival in menopausal women bearing aggressive tumors

-

•

Beta-hCG’s tumorigenic effects are amplified in the absence of the ovaries

-

•

Progesterone dampens beta-hCG-driven tumorigenesis via non-nuclear receptors

-

•

Many post-menopausal tumors preferentially express non-nuclear progesterone receptors

Cancer; Cell biology; Physiology

Introduction

During menopause, the ovaries lose the ability to respond to pituitary hormones, resulting in a cessation in the production of ovarian steroids. The post-menopausal state can be accompanied by several clinical symptoms (Dalal and Agarwal, 2015). In particular, post-menopausal women display a higher risk of cancers of different lineages, such as the colon and lung (Franceschi et al., 2000; Min et al., 2017). The risk of glioma and breast carcinoma is also enhanced, being also influenced by age at menarche and menopause (Huang et al., 2004; Surakasula et al., 2014). The number of deaths owing to cancer in post-menopausal women is expected to increase by 70% in the next 20 years, and enhancing understanding of post-menopausal biology as it relates to the clinical management of cancer is, therefore, of some importance.

Interestingly post-menopausal women frequently display elevated levels of either the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (El Hage and Hatipoglu, 2021; Snyder et al., 2005) or its beta subunit (beta-hCG) (Bashir et al., 2006; Daiter et al., 1994), believed to be of pituitary origin (Bashir et al., 2006; Daiter et al., 1994; El Hage and Hatipoglu, 2021). The presence of beta-hCG could be indicative of ectopic implantation (Surampudi and Gundabattula, 2016), the presence of germ cell or gestational tumors (Dieckmann et al., 2019; Jagtap et al., 2017), or certain non-trophoblastic neoplasias (Iles et al., 1990). Although placental hCG has well-established physiological roles in pregnancy, the hormone (or more commonly beta-hCG) is also ectopically produced by tumors and may possess pro-tumorigenic attributes (Iles et al., 1990; Nakanuma et al., 1986; Wong et al., 2015; Yamaguchi et al., 1989). For example, hCG or its beta subunit can positively influence neoplastic transformation by aiding processes such as invasion (Cole, 2012; Li et al., 2018; Khare et al., 2016) metastasis (Wu et al., 2019), and chemoresistance (Sahoo et al., 2015). Of note, the presence of beta-hCG in patients with cancer has been associated with tumor aggressiveness (Guo et al., 2011; Hameed et al., 1999) and with poor prognosis (Li et al., 2018; Venyo et al., 2010).

The correlation between the presence of beta-hCG, the post-menopausal state, and the risk of oncogenesis remains enigmatic, and whether ovarian steroids can mediate a protective role is worthy of investigation. This work attempted to shed some light on this matter. In vitro studies demonstrated the apoptosis-inducing effects of ovarian steroids on beta-hCG responsive tumor cells; a subsequent focus on progesterone led to the delineation of the mechanisms of cytotoxic action mediated by the steroid. Two observations were of significance; firstly, the cytotoxic effects of progesterone were mediated via non-nuclear receptors, and secondly, neither hCG nor beta-hCG could inhibit the cytotoxic effects of progesterone on tumor cells, unlike their protective effects against a conventional chemotherapeutic drug.

Beta-hCG transgenic mice provided an ideal model for the critical evaluation of the anti-tumor effects of progesterone in vivo; ovariectomy in such mice could serve as a mimic of the post-menopausal state, where implanted tumors would be exposed to beta-hCG in the absence of ovarian steroids. The fact that tumor cells grew more aggressively in ovariectomized animals was instructive. Furthermore, the administration of progesterone to ovariectomized, tumor cell-implanted beta-hCG transgenic mice effectively reversed the exaggerated tumor growth induced on ovariectomy. Essentially, progesterone appeared to compensate for the lack of the ovaries.

Transcriptome profiling of tumors isolated from transgenic mice, ovariectomized transgenic mice, as well as from ovariectomized transgenic mice treated with progesterone, added another dimension to this study. The identity of several well-known pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic genes that were modulated both as a consequence of ovariectomy, as well as by the action of progesterone in a beta-hCG-containing milieu, was revealed. Additionally, reference to TCGA databases provided critical clinical relevance in the context of some aggressive human cancers, particularly relevant to post-menopausal status; the expression of intra-tumoral beta-hCG, as well as of several progesterone-influenced, tumor-associated genes correlated with poorer prognosis specifically in post-menopausal women, as compared to the pre-menopausal cohort.

These findings are novel and of potential clinical significance. Murine tumor-associated gene signatures, combined with queries on aggressive human tumors reveal, for the first time, that beta-hCG acts as an additionally potent pro-tumorigenic signal when the ovaries are quiescent. Collectively, they suggest that, in post-menopausal women, the combination of low progesterone and an increase in beta-hCG can enhance cancer progression. Interestingly, analysis of TCGA databases revealed that tumors in post-menopausal women also predominantly express non-nuclear progesterone receptors. The data reported here strengthens the case for progesterone-based therapeutics in beta-hCG-expressing post-menopausal women with cancer.

Results

Ovarian steroid hormones exhibit growth inhibitory effects on LLC1 tumor cells

The effects of ovarian steroids on LLC1 tumor cells (in terms of cell viability, proliferation, and the induction of apoptosis) were first assessed in vitro. Controls included incubating cells with either vehicle or cholesterol; viability analysis did not include cholesterol as a control, given it’s known interference with the MTT assay (Ahmad et al., 2006). Both progesterone and estradiol induced a dose-dependent decrease in LLC1 tumor cell viability (Figure 1A) as well as in proliferative responses (Figure 1B), compared with relevant controls. A dose-dependent increase in the binding of Annexin-V to LLC1 tumor cells (indicative of apoptosis) was also observed (Figure 1C). Of note was the fact that progesterone, particularly at higher concentrations, was more effective than estradiol in its effects, both at reducing cell viability and inducing apoptosis. The ability of the two steroids to induce apoptosis was further confirmed by fluorescence microscopy; incubation of LLC1 tumor cells with the respective steroids led to enhanced binding of Annexin-V-FITC and propidium iodide, compared with relevant controls (Figure 1D). Co-incubation of LLC1 tumor cells with sub-optimal doses of both steroids had additive effects on the induction of apoptosis (Figure 1E). Studies on A549 cells (a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line) provided further validation of their cytotoxic effects; similar detrimental effects on cell viability (Figure S1A) and proliferation (Figure S1B) were observed.

Figure 1.

Ovarian steroid hormones exhibit growth inhibitory effects on LLC1 tumor cells

(A) LLC1 tumor cells were incubated with varying concentrations (0.1-100 μM) of progesterone (Prog) or estradiol (Est) for 48 h. Veh: Vehicle (ethanol). Cell viability was assessed by MTT. Data are plotted as percentage viability over untreated cells. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). Each value was compared to highest concentration of Veh. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

(B) Experimental setup identical to Figure 1A. Proliferation was assessed by measuring the incorporation of 3H-thymidine. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). Each value was compared with corresponding values of the negative control cholesterol (Choles). ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test. UT: Untreated cells.

(C) Experimental setup identical to Figure 1A. Annexin-V expression was assessed by flow cytometry. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). Each value was compared with corresponding values of the negative control (Choles). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

(D) Fluorescence images of LLC1 tumor cells incubated with respective steroids, with cholesterol (Choles) (50 μM), or with the vehicle (Veh) for 24 h and then stained with Annexin-V-FITC and propidium iodide.

(E) LLC1 tumor cells were individually incubated with Prog, Est, or Choles (30 μM), or with the indicated combinations, for 48 h. Annexin-V expression was assessed by flow cytometry. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by the unpaired t-test.

Progesterone mediates its effects via non-nuclear receptors on LLC1 tumor cells

Further studies focused on the effects of progesterone because of its greater relevance to subsequent in vivo experimentation. At the outset, attempts were made to delineate the receptors responsible for progesterone action on LLC1 tumor cells. Steroids generally act through classical/nuclear receptors (Jacobsen and Horwitz, 2012; Lösel and Wehling, 2003). Unlike in the ovaries, LLC1 tumor cells, however, were found to not express mRNA for the nuclear progesterone receptors Pgr-A or Pgr-B (Figure 2A, Data S1). As steroid-induced expression of nuclear receptors has been described (Diep et al., 2016), levels of nuclear receptor mRNA were also assessed 24 h post-treatment with progesterone; specific increase over vehicle treatment was not observed (Figure S2, Data S1). Nevertheless, whether even vehicle-induced increase in nuclear receptors occurring over the course of the experiment could play a role in progesterone-mediated effects was assessed. Mifepristone (a nuclear progesterone receptor antagonist) was unable to reverse the effects of progesterone on LLC1 tumor cell viability (Figure 2B) or proliferation (Figure 2C). Taken together, the data strongly suggest that progesterone-mediated cytocidal effects on LLC1 tumor cells are not a consequence of events dependent on the presence of classical/nuclear progesterone receptors.

Figure 2.

Progesterone mediates its effects via non-nuclear receptors on LLC1 tumor cells

(A) Expression of the mRNA for nuclear progesterone receptor (Pgr) in LLC1 tumor cells. 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA, and PCR was carried out. mRNA from BALB/c ovaries was employed as a positive control (PC). The primer employed (sequence provided in Table S2) amplifies both isoforms (A and B) of Pgr. The vertical gap between the bands denotes missing wells in the gel (Data S1). Gapdh controls are shown.

(B) LLC1 tumor cells were incubated with mifepristone (500 nM) for 12 h followed by incubation with Prog (50 μM) for 48 h. Vehicle (Veh) for mifepristone: DMSO; Veh for mifepristone + Prog: DMSO + ethanol. Cell viability was assessed by MTT. Data are plotted as percentage viability over untreated cells. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test. ns: non-significant.

(C) Experimental set-up similar to Figure 2B. Proliferation was assessed by measuring the incorporation of 3H-thymidine. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by the unpaired t-test.

(D) Expression of mRNA for non-nuclear progesterone receptors in LLC1 tumor cells. mRNA from BALB/c ovaries was employed as a positive control (PC). 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA, and PCR was carried out. The vertical gap between the bands denotes missing wells in the gels (Data S1). Gapdh controls are shown.

(E) LLC1 tumor cells were incubated with phosphodiesterase inhibitors IBMX and Ro-20-1724 for 30 min before incubation with forskolin (100 μM/10 min) or Prog (100 μM/30 min). Vehicle (Veh) for forskolin: DMSO. A luminescence-based assay for cAMP was then performed. Each luminescence (RLU) value was normalized to blank. Concentrations were calculated using four-parameter logistic curve regression model. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 2). Value compared to respective vehicles. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

Several non-nuclear receptors for progesterone have been described (Garg et al., 2017). Interestingly, just like the ovaries, LLC1 tumor cells expressed mRNA for several such receptors (Figure 2D, Data S1). To assess whether progesterone non-nuclear receptors on LLC1 tumor cells had functional roles, two hallmarks associated with non-classical signaling were evaluated—the activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (described below), and an influence on cAMP levels. Consistent with previous reports (Garg et al., 2017), the data indicated that progesterone, unlike forskolin, did not induce increases in intracellular cAMP levels in LLC1 tumor cells (Figure 2E). Assays at varying doses (50 μM, 70 μM) and time points (5 min, 15 min) yielded similar data (not shown). Overall, these experiments led to the conclusion that non-nuclear receptors, and not the nuclear isoforms, are associated with the effects of progesterone on LLC1 tumor cells.

Progesterone-induced cell death is at least partly mediated by the activation of p38

Whether MAP kinase pathways were activated in response to signaling via non-nuclear receptors, and whether such events were associated with progesterone-induced loss of LLC1 tumor cell viability, were then evaluated. Post progesterone incubation, cell lysates were probed with antibodies to phosphorylated and total JNK, ERK, and p38. Interestingly, while the ethanol-containing vehicle induced background phosphorylation of ERK and p38 (albeit with differing kinetics) as also reported in other systems (Ku et al., 2007), progesterone effectively dampened these effects at most timepoints. Furthermore, analysis of data at 20 min revealed evidence of specific progesterone-induced phosphorylation of JNK and p38. In contrast, progesterone treatment appeared to down-modulate phospho-ERK levels at 20 min (Figure 3A, Data S2, Figure 3B). In order to assign functional relevance to these observations, specific inhibitors for JNK, ERK, and p38 were employed; while phosphorylation of JNK and p38 was once again observed on progesterone treatment, pre-incubation with the inhibitors resulted in significant inhibitory effects on the phosphorylation of the MAP kinases, as expected (Figures 3C–3E, Data S2). The viability of cells individually pre-incubated with each inhibitor and subsequently with progesterone was then evaluated by assessing ATP release. Although the inhibition of ERK and JNK phosphorylation significantly enhanced the loss of viability induced by progesterone (owing to reasons not yet clear), inhibition of p38 phosphorylation significantly ameliorated progesterone-induced cell death (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Progesterone-induced cell death is at least partly mediated by the activation of p38

(A) LLC1 tumor cells were incubated with Prog (50 μM) or the vehicle (Veh) for the indicated timepoints. Lysates were then assessed for evidence of MAPK activation by Western blot. The vertical gaps between the data for Veh and Prog for each antibody indicate separate blots; blots were exposed to the same X-ray film to ensure equal exposure to chemiluminescent signals (Data S2). Reactivity of antibodies recognizing phosphorylated (P) and total (T) MAPKs are shown. Gapdh controls are also shown. Data for P-JNK, JNK, Gapdh (Veh and Prog), P-p38 (Prog), and p38 (Prog) are mirror images of the original (Data S2). Densitometry was performed on raw data.

(B) Densitometry analysis of data in Figure 3A. Each phospho (P) band at 20 min was normalized to its corresponding band indicating total (T) reactivity. Fold change in phosphorylation (Prog vs Veh) at 20 min is represented. Values represent arithmetic mean fold change ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

(C) LLC1 tumor cells were incubated with inhibitors (i) for ERK (PD98059), JNK (JNK II inhibitor), or p38 (SB203580) (20 μM) for 1 h followed by treatment with Prog (50 μM) for 20 min. Veh for i + Prog: DMSO + ethanol. Lysates were then assessed for evidence of MAPK activation by Western blot. Reactivity of antibodies recognizing phosphorylated (P) and total (T) MAPKs are shown. Gapdh was employed as control; one representative experiment is shown. The Veh (Prog) and Prog lanes for Gapdh have been used across this representation, as they comprise samples from the same experiment.

(D) Densitometry analysis of data in Figure 3C. Each phospho (P) band was normalized to its corresponding band indicating total (T) reactivity. Fold change in phosphorylation (Prog vs Veh) at 20 min is represented. Values represent arithmetic mean fold change ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

(E) Densitometry analysis of data in Figure 3C. Each phospho (P) band was normalized to its corresponding band indicating total (T) reactivity. Fold change in phosphorylation (i + Prog vs Prog) at 20 min is represented. Values represent arithmetic mean fold change ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

(F) LLC1 tumor cells were pre-incubated with indicated inhibitors (i, 20 μM) for 1 h followed by treatment with Prog (15 μM) for 24 h. Intracellular ATP was measured to assess cell viability. Data are plotted as percentage viability over untreated cells. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

The activation of MAP kinases confirms the involvement of non-classical signaling via non-nuclear receptors in the growth inhibitory effects of progesterone on LLC1 tumor cells. More specifically, while experimental limitations prevented more effective inhibition of MAP kinase phosphorylation, the data make evident the involvement of the p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway in the mediation of progesterone-induced cell death.

Characterization of progesterone-induced apoptosis in LLC1 tumor cells

To gain further insight into the nature of progesterone-induced cell death in LLC1 tumor cells, the status of prominent apoptotic mediators was evaluated. Progesterone exposure resulted in an increase in the mRNA levels of Fas, Fas ligand (FasL) as well as BCL-2 antagonist/killer (BAK1); mRNA levels for the BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX), however, remained unchanged (Figures 4A and 4B, Data S1). Evidence of the cleavage of caspase 8 and caspase 9 (both “initiator” caspases) was also obtained on progesterone exposure. Although procaspase 3 (an “executioner” caspase) was also cleaved on progesterone treatment, caspase 7 (another “executioner” caspase) was not (Figure 4C, Data S2). Interestingly, while progesterone induced the up-modulation of apoptosis-related molecules as well as activated the caspase cascade, the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk could only partially rescue LLC1 tumor cells from progesterone-induced loss of cell viability (Figure 4D), evidence that alternative mechanisms of cell death could also play a prominent role.

Figure 4.

Characterization of progesterone-induced apoptosis in LLC1 tumor cells

(A) LLC1 tumor cells were incubated with vehicle (Veh) or Prog (50 μM) for 24 h. 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA, and PCR for the indicated genes was carried out. Gapdh controls for the same experiment are shown. Each image is a mirror image of the original lanes in the gel (Data S1).

(B) Densitometry analysis of data in Figure 4A. Band intensities were normalized to respective Gapdh controls. Fold change in expression in Prog vs Veh treatment is shown. Values represent arithmetic mean fold change ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by the unpaired t-test.

(C) LLC1 tumor cells were incubated with Veh or Prog (50 μM) for 24 h. Lysates were then assessed for evidence of caspase activity by Western blot, employing antibodies to indicated caspases (pro and cleaved-Cl). The vertical gap between the blots for caspases 3 and 9 implies missing bands within a blot (for caspase 3) or separate blots (for caspase 9) and the horizontal gap for a given caspase denotes splitting of the same blot to efficiently capture pro- and cleaved fragments separately. Blots were exposed to the same X-ray film to ensure equal exposure to chemiluminescent signals (Data S2). Caspase 8 (pro and cleaved) are mirror images of the raw data. Gapdh controls (mirror image of original data) for one representative experiment are shown.

(D) LLC1 tumor cells were co-incubated with a pan-caspase inhibitor (zVAD, 75 or 100 μM) and Prog (10 μM) for 24 h. Veh for zVAD: DMSO; Veh for zVAD + Prog: DMSO + ethanol. Intracellular ATP was measured to assess cell viability. Data are plotted as percentage viability over untreated cells. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test.

(E) LLC1 tumor cells were co-incubated with hCG (1 μg/mL, 0.026 μM; 13,000 IU/mg) and Prog (50 μM), or with beta-hCG (0.026 μM) and Prog for 24 h. Veh for hCG/beta-hCG: PBS; Veh for Prog + hCG/beta-hCG: ethanol + PBS. Cell viability was assessed by MTT. Data are plotted as percentage viability over untreated cells. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the unpaired t-test. ns: non-significant.

(F) Experimental setup identical to Figure 4E. Lysates were probed with an anti-caspase 3 antibody by Western blot. The vertical gap in between columns representing pro- and cleaved-caspase 3 denotes splitting of the same blot to efficiently capture pro- and cleaved fragments separately. Blots were exposed to the same X-ray film to ensure equal exposure to chemiluminescent signals (Data S2). Gapdh controls for a representative experiment are shown. 24 h data are represented.

Previous work had established that both hCG (Sahoo et al., 2015) and beta-hCG (unpublished data) protect tumor cells from chemotherapeutic agents such as tamoxifen which induces caspase-mediated death (Mandlekar et al., 2000), a property that aligns with the fact that patients with cancer with high serum beta-hCG levels often respond poorly to chemotherapy (Szturmowicz et al., 1995), and its presence is negatively associated with patient prognosis (Li et al., 2018). In the present study, while hCG and beta-hCG ameliorated the tamoxifen-induced loss in LLC1 tumor cell viability as expected (Figure S3), neither hCG nor beta-hCG reduced progesterone-induced loss of LLC1 tumor cell viability (Figures 4E and S3). In line with these observations, progesterone-induced cleavage of caspase 3 was also not prevented by either hCG or beta-hCG (Figure 4F, Data S2). Although a detailed characterization of the pathways of cell death mediated by progesterone in tumor cells is ongoing, these results suggest that, in contrast to when a chemotherapeutic drug such as tamoxifen is employed, hCG or beta-hCG are unable to mediate cytoprotective effects against the action of progesterone in LLC1 tumor cells.

Progesterone supplementation dampens the enhanced beta-hCG-mediated tumor growth observed in the absence of ovaries in beta-hCG transgenic mice

To assess the in vivo responsiveness of LLC1 tumor cells (originally derived from C57BL/6 mice) to progesterone in a milieu containing beta-hCG, transgenic mice of the appropriate genotype were first generated. Wild-type C57BL/6 female mice were outcrossed with heterozygous beta-hCG transgenic (FVBbeta-hCG/-) male mice. In female F1 mice, genomic DNA PCR was carried out on tail clips to detect the beta-hCG transgene (Figure S4A, Data S1), and radioimmunoassay was carried out to detect beta-hCG in serum (Figure S4B). Assessment of body weight (Figure S4C) and serum prolactin (Figure S4D) further distinguished beta-hCG transgenic female mice from non-transgenic littermates, and histological analysis revealed the presence of pituitary adenocarcinomas in transgenic mice (Figure S4E). Ovaries derived from beta-hCG transgenic mice were characterized by hyper-luteinization, whereas ovaries from non-transgenic littermates exhibited normal histology and the presence of follicles at different stages of development (Figure S4F).

At 5-6 months, some transgenic female mice were ovariectomized; a decrease in serum prolactin levels (Figure S5) confirmed the efficacy of the procedure. 40,000 LLC1 tumor cells were subcutaneously implanted in non-transgenic mice, transgenic mice, and in ovariectomized transgenic mice; tumor volumes were periodically measured. In keeping with a previous study (Singh et al., 2018), two key observations were made. Firstly, LLC1 tumor incidence (Figure S6A), as well as tumor volumes (Figure S6B), were enhanced in beta-hCG transgenic mice compared to non-transgenic littermates. Secondly, ovariectomy led to further enhancement in the growth of LLC1 tumors in beta-hCG transgenic mice, compared with intact beta-hCG transgenic mice (Figure S7).

The effects of progesterone (as well as vehicle) supplementation on the growth of LLC1 tumors in ovariectomized beta-hCG transgenic mice were then assessed. Progesterone efficiently compensated for the absence of ovaries, suppressing the effect of ovariectomy on the growth of LLC1 tumors in transgenic mice (Figures 5A and 5B). A significant difference in tumor volumes was not observed in ovariectomized transgenic vehicle-treated mice vs ovariectomized transgenic untreated mice (Figure S8), validating the data described above. At 30 days post-implantation, mice were euthanized and tumors harvested. Excised tumors were subjected to RNA-sequencing and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by performing DESeq analysis; the two primary comparisons made were between tumors isolated from (1) transgenic (TG) mice vs ovariectomized-TG-vehicle treated (OVX-TG-Veh) mice, and from (2) OVX-TG-Veh mice vs ovariectomized-TG-progesterone treated (OVX-TG-Prog) mice. Gene expressions with a Log2-fold change (>1 or <1) were attributed as upregulated/downregulated, respectively. From this gene set, differentially expressed genes with an adjusted P-value of ≤0.4 and gene expression value of ≥30 were selected (Figure S9). Genes whose expression levels were enhanced on ovariectomy (in the OVX-TG-Veh gene set) were overlapped with genes whose expression levels declined on progesterone treatment (in the OVX-TG-Prog gene set), and vice versa. This approach helped in the identification of putative progesterone-influenced genes that possibly hindered the process of LLC1 tumorigenesis. A total of 45 genes - 26 heightened on ovariectomy and decreased upon progesterone administration, and 19 decreased on ovariectomy and enhanced on progesterone administration (Figure 5C) - were further screened for potential functional significance (using the DAVID database as well as current literature) and genes identified as having an association with tumorigenesis (with described pro- or anti-tumorigenic functions) were selected for validation. Figure 5D depicts a heatmap of the selected candidate progesterone-influenced genes, and the mouse figurines at the bottom of the map are indicative of respective tumor volumes in the three experimental conditions compared in the study. Ovariectomy led to an increase in the levels of several pro-tumorigenic genes in LLC1 tumors, the expression of which was down-modulated on progesterone treatment. Similarly, many anti-tumorigenic genes were down-modulated in LLC1 tumors in the absence of the ovaries and up-modulated on the administration of progesterone. In other words, on the administration of progesterone to ovariectomized transgenic mice, mRNA levels of genes associated with tumorigenesis in LLC1 tumors tended to revert to levels observed in LLC1 tumors isolated from intact transgenic mice, mirroring the effect of progesterone administration on LLC1 tumor volumes. Such analysis, therefore, revealed molecular signatures associated with enhanced beta-hCG-mediated tumorigenesis when the ovaries are absent. The relative expression levels of several RNA-seq-identified genes were validated by qPCR (Figures 5E and 5F).

Figure 5.

Progesterone supplementation dampens the enhanced beta-hCG-mediated tumor growth observed in the absence of ovaries in beta-hCG transgenic mice

(A) Tumor volumes in transgenic (TG) mice, in ovariectomized transgenic vehicle-treated (OVX-TG-Veh) mice, and in ovariectomized transgenic progesterone treated (OVX-TG-Prog) mice post-implantation of LLC1 tumor cells. Values represent arithmetic mean ± SD (n = 7). ∗∗p < 0.01, OVX-TG-Prog vs OVX-TG-Veh by two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni Multiple Comparison Test.

(B) Representative pictures of tumors in mice from the three groups on Day 30.

(C) Venn diagrams indicating differentially expressed genes in tumors excised from the different groups of mice. Tumors were harvested at thirty days post-LLC1 tumor cell implantation, RNA-sequencing was carried out and differentially expressed genes were identified. For OVX-TG-Veh, “LOW” (green Venn diagram) and “HIGH” (blue Venn diagram) refer to the number of genes in tumors from OVX-TG-Veh mice whose levels were either decreased or enhanced, respectively, in comparison with the genes in tumors from TG mice. For OVX-TG-Prog, “LOW” (yellow Venn diagram) and “HIGH” (pink Venn diagram) refer to the number of genes in tumors from OVX-TG-Prog mice whose levels were either decreased or enhanced, respectively, in comparison with the genes in tumors from OVX-TG-Veh mice (Also refer to Figure S9). The “∗” indicates genes potentially influenced by Prog, where ovariectomy-induced changes are reversed on Prog administration. Two tumors from two different mice belonging to the same group were included for RNA-seq analysis.

(D) Heatmap depicting “pro-tumorigenic genes” (up-modulated on ovariectomy and down-modulated on progesterone administration) and “anti-tumorigenic genes” (down-modulated on ovariectomy and up-modulated on progesterone administration). Mouse figurines at the bottom of the figure represent LLC1 tumor volumes in the three groups of mice.

(E) qPCR validation of modulation (OVX-TG-Veh vs TG) in mRNA levels of genes represented in the heat map (Figure 5D). Ct values of each gene were normalized to actin and the ΔΔCt method was applied for the quantification of relative mRNA levels. Values represent arithmetic mean fold change ± SD (n = 3). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; OVX-TG-Veh vs TG by the unpaired t-test.

(F) qPCR validation of modulation (OVX-TG-Prog vs OVX-TG-Veh) in mRNA levels of genes represented in the heat map (Figure 5D). Ct values of each gene were normalized to actin and ΔΔCt method was applied for the quantification of relative mRNA levels. Values represent arithmetic mean fold change ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; OVX-TG-Prog vs OVX-TG-Veh by the unpaired t-test.

(G) Immunohistochemical analysis depicting reactivity of antibodies against the indicated molecules in tumor sections derived from TG mice, OVX-TG-Veh mice, or OVX-TG-Prog mice. Scale: 40 μm.

Immunohistochemical analysis was carried out on sections derived from excised tumors to visualize protein products encoded by some of the identified genes. On tumor sections, in several instances, ovariectomy enhanced the expression of proteins classified as “pro-tumorigenic,” and administration of progesterone to ovariectomized transgenic mice reduced the expression to that observed in tumor sections from intact transgenic mice, providing further validation of the steroid’s anti-tumor effects. Curiously, levels of Cxcl9 (an “anti-tumorigenic” protein) on tumor sections across the three groups were not in consonance with its mRNA levels as determined both by RNA-seq and qPCR, the reasons for which remain at present unclear. While histological sections depicting these results are shown in Figure 5G, data are summarized in Table S1.

As with LLC1 tumor cells in culture, LLC1 tumors isolated from TG, OVX-TG-Veh or OVX-TG-Prog mice did not express nuclear progesterone receptors, but did express several non-nuclear progesterone receptors, as revealed by both RNA-seq analysis (Figure S10A) as well as semi-quantitative PCR (Figure S10B, Data S1); mRNA levels did not vary substantially or consistently across the three groups. These results represent strong evidence that non-nuclear progesterone receptors mediate the steroid’s anti-tumor effects in vivo as well.

It was also of interest to determine if LLC1 tumor cells expressed the conventional LH/CG receptor (the cognate receptor for hCG). Evidence for such expression could not be obtained, either for LLC1 tumor cells grown in culture (Figure S11A, Data S1), or for tumors excised from the three different groups of mice by RNA-seq analysis (Figure S11B) or by semi-quantitative PCR (Figure S11C, Data S1). It can be surmised that the actions of beta-hCG in this system are mediated by a moiety other than the conventional LH/CG receptor, the identity of which presently remains unknown.

Progesterone-influenced molecular profile identified by RNA-seq in murine tumors displays clinical relevance

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was probed with the tumor-associated progesterone-influenced genes identified in this study, with the ultimate aim of delineating the possible relevance of the findings to cancers in post-menopausal women. As previously indicated, this sub-group of women displays a higher risk of cancers of different lineages, such as lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD), and glioblastoma GBM (Franceschi et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2004; Min et al., 2017). Hence, TCGA databases for LUAD, COAD, and GBM were employed in this study.

Initial analysis, which included subjects from both sexes and all age groups, mapped the human counterparts of genes identified in this study as being potentially influenced by progesterone in beta-hCG transgenic mice. Interestingly, in several instances, the expression patterns of these murine genes overlapped with the expression patterns of their corresponding human orthologs in the TCGA database.

The “anti-tumorigenic genes” TIMP3, TP53INP1, and SFRP2, which were all up-modulated on progesterone treatment in mice, were also expressed at higher levels in healthy human tissues compared to levels in the three tumor lineages, in a variable manner. Alternatively, “pro-tumorigenic genes” such as LGALS7, MMP10, TNFRSF9, MMP3, MMP12, MMP1, SPP1, and ERO1A (also known as ero1l in mice), down-modulated on progesterone treatment in transgenic mice, were expressed at higher levels across the three tumor lineages than in healthy tissue, in a variable manner (Figures 6A and S12A, and S12B).

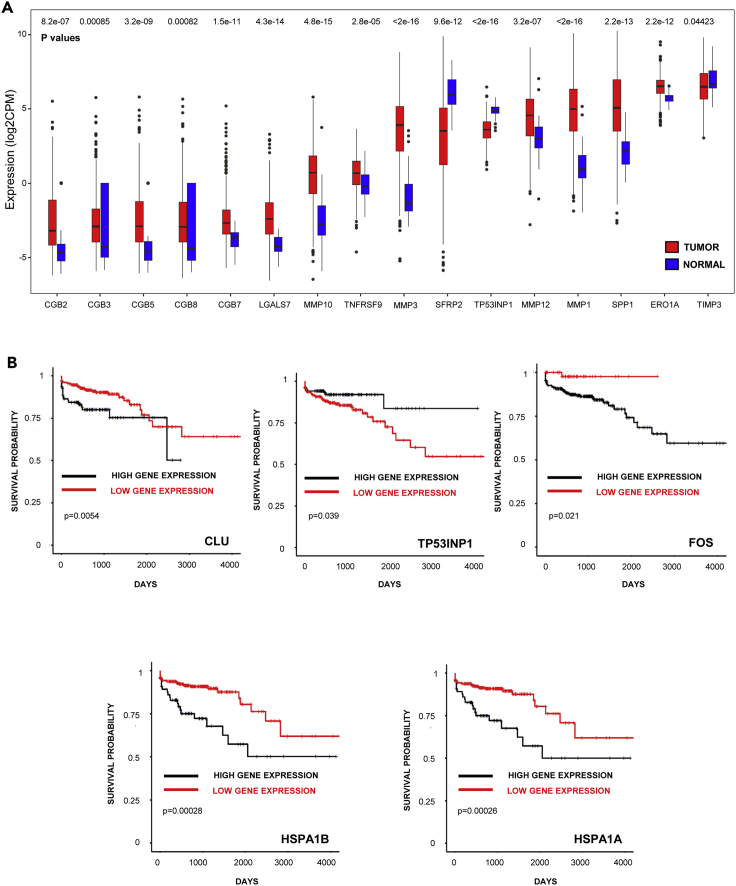

Figure 6.

Progesterone-influenced molecular profile identified by RNA-seq in murine tumors displays clinical relevance

(A) Expression of the indicated genes in COAD (n = 480) and normal tissue (n = 41). The Wilcoxon test was employed to determine significance, depicted above respective bars.

(B) Survival analysis of patients with COAD with either high expression or low expression of CLU (n, high/low = 393/62), TP53INP1 (n, high/low = 150/305), FOS (n, high/low = 393/62), HSPA1B (n, high/low = 380/75) or HSPA1A (n, high/low = 382/73). The Log-rank test was employed to determine significance, depicted in each panel.

Of immediate relevance to this study, several known non-allelic genes encoding beta-hCG (CGB2, CGB3, CGB5, CGB8, and CGB7) were found to be variably up-modulated in COAD and LUAD (Figures 6A and S12B); the GBM dataset also displayed expression of beta-hCG, albeit at much lower levels (data not shown). TCGA analysis also indicated that patients with LUAD with tumors expressing higher amounts of beta-hCG genes (CGB8 and CGB3) have poorer survival compared to patients with tumors that displayed lower levels of this hormone (data not shown), in line with multiple reports linking tumor-associated beta-hCG with poor patient prognosis.

Interestingly, the expression status of several genes identified in this study demonstrated associations with patient survival, variably across COAD and GBM. For example, high expression levels of CLUSTERIN, FOS, HSPA1B, HSPA1A, TNFRSF9, FOSB (“pro-tumorigenic genes” as per the murine model) correlated with poorer survival, whereas high levels of TP53INP1 and CXCL9 (“anti-tumorigenic genes” as per the murine model) correlated with enhanced survival (Figures 6B and S13).

Progesterone-influenced molecular profile identified by RNA-seq in murine tumors underscores the onco-protective nature of the pre-menopausal reproductive stratum in women

The TCGA database was also probed with human orthologs of genes shortlisted in the transgenic model with the menopausal status of women being the qualifier, the logic being that ovariectomy in mice induces a state analogous to the post-menopausal stratum in women. Interestingly, high expression of the “pro-tumorigenic gene” (as defined by the transgenic model and enhanced on ovariectomy) MMP10 in COAD tumors was associated with poorer survival in post-menopausal women compared with pre-menopausal women; while poorer survival was also observed for post-menopausal women harboring GBM tumors expressing high levels of MMP3, an adequate population of pre-menopausal women expressing high levels of MMP3 in GBM tumors was unavailable for comparison in the database (Figures 7A and 7B, left and center panels). Collectively, the data suggested that the impact of these progesterone-influenced genes identified to be “pro-tumorigenic” in ovariectomized transgenic mice on prognosis is dependent on the presence of a functioning ovary in women.

Figure 7.

Progesterone-influenced molecular profile identified by RNA-seq in murine tumors underscore the onco-protective nature of the pre-menopausal reproductive stratum in women

(A) Survival analysis of post-menopausal women (POST) with either high expression and low expression of MMP10 (in COAD; n, high/low = 96/67), MMP3 (in GBM; n, high/low = 4/39) or CGB3 (in LUAD; n, high/low = 103/129). The Log -rank test was employed to determine significance, depicted in each panel.

(B) Survival analysis of pre-menopausal women (PRE) with either high expression or low expression of MMP10 (in COAD; n, high/low = 24/28), MMP3 (in GBM; n, high/low = 0/16) or CGB3 (in LUAD; n, high/low = 19/34). The Log -rank test was employed to determine significance, depicted in each panel.

(C) Survival analysis of post-menopausal (POST) and pre-menopausal (PRE) women with high expression of LGALS7 (in COAD; n, post-menopause/pre-menopause = 62/21), MMP1 (in GBM; n, post-menopause/pre-menopause = 18/4), SPP1 (in GBM; n, post-menopause/pre-menopause = 37/10) or CXCL9 (in GBM; n, post-menopause/pre-menopause = 36/13). The Log-rank test was employed to determine significance, depicted in each panel.

Whether expression levels of the identified progesterone-influenced genes differentially correlated with patient prognosis in pre-menopausal vs post-menopausal women was also assessed by an alternate analysis. High expression of the “pro-tumorigenic gene” (as defined by the transgenic model and enhanced on ovariectomy) LGALS7 (in COAD) was associated with poor survival specifically in the post-menopausal stratum. Furthermore, high expression of MMP1 (in GBM) and SPP1 (in GBM), other “pro-tumorigenic genes,” was also associated with poorer survival only in post-menopausal women (Figure 7C). Interestingly, low expression of “pro-tumorigenic genes” such as TNFRSF9, MMP3, and LGALS7 in GBM tumors was also specifically associated with poorer prognosis in post-menopausal women (Figures S14A–S14C). Also, high expression of the “anti-tumorigenic genes” (as defined by the transgenic model and enhanced on progesterone supplementation) such as CXCL9 (in GBM tumors) displayed correlation with enhanced survival in pre-menopausal women (Figure 7C).

To summarize, human orthologs of some of the genes identified as “pro-tumorigenic” based on studies in transgenic mice (that is, genes up-modulated in tumors in the absence of ovaries, and down-modulated in tumors on the administration of progesterone) were preferentially associated with poor prognosis in post-menopausal women, and evidence for the protective effects of “anti-tumorigenic genes” in pre-menopausal group was also obtained. Collectively, these studies outline the onco-protective influence of reproductive hormones in general, and of progesterone in particular.

TCGA analysis also revealed several interesting correlates of intra-tumoral beta-hCG with patient prognosis. High expression of CGB3 in LUAD tumors was associated with poorer survival in post-menopausal women (Figures 7A and 7B, right panels), as was a low expression of CGB1 in GBM tumors (Figure S14D).

Discussion

Intra-tumoral hCG/beta-hCG, generally associated with advanced-stage, poorly differentiated cancers, display pro-tumorigenic properties, such as aiding tumor cell invasion (Li et al., 2018) and metastasis (Wu et al., 2019), and are also linked with poor patient prognosis (Crawford et al., 1998; Douglas et al., 2014; Iles et al., 1996; Li et al., 2018; Szturmowicz et al., 1995; Sheaff et al., 1996; Venyo et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 1989).

Two additional facts are of direct relevance to this study and its derivative implications: Firstly, several cancers, including glioblastoma, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer, occur at an increased frequency in the post-menopausal stratum (Franceschi et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2004; Min et al., 2017), a fact that naturally draws attention to the potentially protective influence of female reproductive hormones. In patients with colorectal cancer, better survival in young women (as compared to men of the same age, or older women) has been attributed to estradiol (Abancens et al., 2020). The use of natural progesterone in post-menopausal women is linked with a lower risk of breast cancer (Lieberman and Curtis, 2017), and hormonal therapy has been reported to lower the risk of colorectal cancer (Botteri et al., 2017) and associated mortality (Jang et al., 2019). Secondly, post-menopausal women, even in the absence of tumors, can display high levels of hCG (Snyder et al., 2005) or beta-hCG (Bashir et al., 2006; Daiter et al., 1994). Whether there might exist a cause-effect relationship between these two observations is currently unknown; in other words, the potential role beta-hCG (both intra-tumoral and extra-tumoral) might play in the pathophysiology of cancers in post-menopausal scenarios remains unexplored. The current study was based on testing the hypothesis that ovarian hormones can exert an ameliorating influence on the growth of beta-hCG responsive tumor cells in vitro as well as in vivo.

In this work, both progesterone and estrogen were shown to negatively impact the growth and survival of LLC1 tumor cells. These cells are derived from granular pneumocytes, equivalent to human alveolar cell carcinoma (Garcia-Sanz et al., 1989). The steroids were shown to have inhibitory effects on the growth of A549 cells (a human alveolar carcinoma cell line) as well. The inhibitory effects of progesterone, in terms of the migration and invasion of A549 cells, have also been described in other studies (Xie et al., 2013). Such lineage-associated, cross-species complementary data increase the relevance of current observations. The anti-tumorigenic effects of ovarian steroids on cancers of different lineages have been previously described as well (Lee et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2017). Although a combination of estradiol and progesterone has been reported to increase the proliferation of breast cancer cells (Tian et al., 2018) and confer chemoresistance to lung cancer cells (Grott et al., 2013), the present study suggested additional inhibitory effects on the viability of LLC1 tumor cells on the combination of the two steroids. In line with this observation, combinational hormone replacement therapy with progestogen and estrogen has been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of endometrial cancer (Mayor, 2015). Clearly, the effects of steroid combination therapy appear to be context-dependent, and further investigations are required to unequivocally delineate the conditions under which such therapy would be beneficial.

Going forward, two factors prompted a focus on progesterone, rather than on estradiol, in this study. Firstly, in vitro data indicated that progesterone was more potent than estradiol in causing the apoptosis of LLC1 tumor cells, particularly at high doses. Secondly, work by other investigators revealed a significant increase in serum progesterone (and not estradiol) levels with age in beta-hCG transgenic mice (Rulli et al., 2002), an animal model subsequently employed in this work. It was, therefore, reasoned that studying the biology of progesterone in the context of beta-hCG-mediated tumorigenesis would be appropriate and logical.

Progesterone, while being central to reproductive function, also plays regulatory roles in other tissues, including the brain (Brinton et al., 2008), the breast (Druckmann, 2003), and the bone (Seifert-Klauss and Prior, 2010). Its action primarily involves nuclear progesterone receptor (nPR)-associated classical signaling events. These receptors are known to function as ligand-dependent transcription factors. Two well-characterized isoforms of nPRs exist; PR-A and PR-B (Garg et al., 2017). Interestingly, although progesterone mediated significant effects on LLC1 tumor cells in the current study, the cells did not express nuclear progesterone receptors, and neither were such receptors enhanced on progesterone incubation over levels induced by ethanol, a previously described property of the vehicle (Etique et al., 2007). Experiments employing the nPR antagonist mifepristone further confirmed that the observed effects of progesterone on LLC1 tumor cells were not mediated by nuclear receptors, but possibly via other cognate progesterone receptors.

Recent studies have revealed the identity of several non-nuclear receptors associated with progesterone action in the context of both physiological (Gellersen et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2013) and pathological (Pedroza et al., 2020) conditions. Such receptors include several subtypes of membrane-bound progesterone receptors/progestin and adipoQ receptors (paqrs), PGRMC1/2, and GABA-A receptors (Garg et al., 2017). In the present study, transcripts for several Paqr and Pgrmc receptors were detected in LLC1 tumor cells, and on-going investigations aim at delineating the particular receptor(s) responsible for progesterone action. The progesterone non-nuclear receptor complex is known to act via non-classical mechanisms, including the inhibition of adenyl cyclase and cAMP, as well as the activation of MAPKs (Garg et al., 2017). Current observations were consistent with previous studies, in that progesterone did not induce an increase in cAMP levels, while it did activate JNK and p38. A lack of progesterone-induced activation of cAMP, as well as the activation of JNK and p38 by the steroid, has also been observed in human ovarian cancer cells, effects also attributed to non-nuclear receptors (Charles et al., 2010).

MAPKs have well-established roles in modulating apoptosis (Yue and López, 2020). The pro-apoptotic functions of p38 have been documented (Dolado et al., 2007), including the activation of caspase 3 (Pearl-Yafe et al., 2004). Progesterone induces apoptosis in HUVECs via p38 (Powazniak et al., 2009), and p38 activation via progesterone-mPR complex has also been proposed to induce apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells (Valadez-Cosmes et al., 2016). Supportive of these reports, the present study demonstrates that inhibiting progesterone-induced activation of p38 can lead to the partial rescue of LLC1 tumor cells from death. It can be surmised that progesterone induces apoptosis in LLC1 tumor cells at least partially via the activation of the p38 pathway subsequent to triggering of the progesterone-mPR complex.

Observations in beta-hCG transgenic mice provided critical insights into the cytopathic effects of progesterone in a beta-hCG-containing milieu. RNA-seq analysis on excised tumors helped reveal the nature of genes that are modulated both by ovariectomy and by progesterone supplementation in beta-hCG transgenic mice. Differential gene expression analysis revealed that the mRNA levels of “anti-tumorigenic genes” such as Timp3, Sulf1, Trp53inp1, Sfrp2, and Ptpn13 (all with well-described pro-apoptotic functions) were diminished on ovariectomy and enhanced on progesterone administration. Though progesterone also induced the activation of both initiator and executioner caspases in LLC1 tumor cells in vitro, data suggest that progesterone-induced cell death may predominantly involve caspase-independent mechanisms, as a pan-caspase inhibitor was only partially effective in rescuing cells from death. Interestingly, TP53INP1 (the human ortholog of mouse Trp53inp1) is also known to induce autophagy-dependent cell death (Shahbazi et al., 2013). Autophagy, originally described as a cell rescue program, can also initiate cell death (Gozuacik and Kimchi, 2004), either acting independently or in conjunction with apoptosis and other regulatory cell death mechanisms (Gozuacik and Kimchi, 2004; Noguchi et al., 2020). Pharmacological interventions that aid apoptosis (Pfeffer and Singh, 2018) or associated regulatory cell death mechanisms such as the pro-death function of autophagy (Linder and Kögel, 2019) in tumors have been considered promising strategies to target cancer cells. Whether autophagy is, indeed, involved in the induction of LLC1 tumor cell death by progesterone is currently unknown but is worth exploring.

As with any work, it is important to put the observations into perspective from a human context. According to the GLOBOCAN Cancer Tomorrow Prediction Tool, the numbers of new cancer cases and deaths in women in the 55-85+ age group are estimated to increase by 58% and 70%, respectively, in the next twenty years. In order to aid in the efficient clinical management of these patients, a better understanding of the post-menopausal state, therefore, remains an exigency. This study provides some clues in this regard.

Intra-tumoral beta-hCG has traditionally been considered an indicator of poor patient prognosis. Interestingly, TCGA analysis revealed that beta-hCG expression (CGB3 in patients with LUAD and the CGB1 in patients with GBM) displayed an association with poorer survival in post-menopausal women, indicating that its presence could have a special pathological significance in this cohort.

Several beta-hCG-driven, progesterone-influenced genes identified in this work are known to play critical roles in the progression of human cancer. Genes such as SPP1, MMP3, MMP1, MMP12, LGALS7, ERO1A, TNFRSF9 identified as “pro-tumorigenic” in the murine model, are expressed at higher levels in human tumors; these genes are known to influence the processes of proliferation, migration, invasion and/or chemoresistance in tumor cells.

Perhaps more significantly, a gene signature identified in this study demonstrated prognostic relevance in cancers particularly associated with the post-menopausal state. In several instances, TCGA analysis revealed an association between the expression of progesterone-influenced “pro-tumorigenic genes” and poor prognosis, specifically in patients with post-menopausal cancer; examples include MMP10, LGALS7 in COAD, and MMP1, SPP1, TNFRSF9, MMP3 and LGALS7 in GBM.

The expression of non-nuclear progesterone receptors seems fairly ubiquitous in tumor cells (Charles et al., 2010; Garg et al., 2017; Pedroza et al., 2020). As with LLC1 tumor cells in culture, tumors from beta-hCG transgenic mice too exclusively expressed non-nuclear progesterone receptors. Furthermore, TCGA analysis revealed that GBM, LUAD, and COAD human tumors also exclusively express non-nuclear receptors for progesterone; while LUAD tumors derived from post-menopausal women express only PAQR6, GBM tumors express higher levels of PGRMC1 and PAQR 6,8, with low expression of PAQR9. COAD tumors from these women display high levels of PGRMC1,2 and PAQR 3,4,5,7,8, while nuclear progesterone receptor expression is insignificant (Figure S15). Whether the presence of such receptors presents a therapeutic opportunity remains an open question.

Overall, this study identifies, for the first time, the inter-relationship between progesterone and beta-hCG in regulating the process of neoplastic transformation. It associates a previously unidentified negative attribute to beta-hCG specifically in the post-menopausal state, while also demonstrating the tumor-suppressing effects of progesterone both in vitro and in vivo. Significantly, levels of several newly identified, beta-hCG driven, progesterone-influenced genes, exhibited correlates with prognosis, specifically in post-menopausal women harboring aggressive cancers. Correlation of intra-tumoral beta-hCG with poorer survival in post-menopausal women, along with data presented in this article, make the case for the evaluation of both extra-tumoral and intra-tumoral beta-hCG as prognostic indicators in tumor-bearing, post-menopausal women.

Beta-hCG did not ameliorate the cytotoxic effects of progesterone on tumor cells, unlike its protective effects against conventional chemotherapeutic drugs, as this study and previous work (Kuroda et al., 1998; Sahoo et al., 2015; You et al., 2010) have shown. The inability of beta-hCG to dampen the cytocidal effects of progesterone could be a useful therapeutic attribute, particularly if the steroid were employed in conjunction with anti-hCG vaccination which has demonstrated, albeit partial, anti-tumor efficacy in several murine systems (Acevedo et al., 1987; Bose et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2010; Khare et al., 2016; Sachdeva et al., 2012; Sahoo et al., 2015) and in humans (Moulton et al., 2002).

The extent of overlap between genes identified in the murine model and their human orthologs as regards potential roles in the ovary deficient/inactive state encourages the use of the model in future investigations seeking to delineate the interplay between chorionic gonadotropin and steroid hormones in the process of tumorigenesis in lineages of particular relevance to the post-menopausal state.

Limitations of the study

The nuclear progesterone receptor was not involved in mediating the steroid’s cytotoxic effects on tumor cells. Although several non-nuclear receptors were present, the precise identity of the receptor(s) which trigger an apoptotic response still awaits elucidation. This is an issue of some importance, as TCGA analysis in this study revealed the predominant presence of several non-nuclear progesterone receptors in tumors derived from post-menopausal women.

While this study suggests the administration of progesterone as a therapeutic in tumor-bearing post-menopausal women (based on the fact that progesterone was demonstrated to “compensate” for the lack of the ovaries in the transgenic murine model in several respects), whether the combined used of estradiol and progesterone (as a more appropriate replacement for the lack of the ovaries) will increase the observed anti-tumor effects is currently unknown, but is worthy of investigation.

Though the current study employed a human hormonal subunit and a steroid common to mice and humans, the use of beta-hCG-associated cancer lineages of human origin and relevant to the post-menopausal age group (in nude mice, or in humanized beta-hCG transgenic mice, for example) could lead to insights of additional clinical relevance.

Additional focus on the genes identified in this study is warranted and could shed further light on mechanisms associated with the regulation of tumors growing under the influence of beta-hCG and progesterone.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOUCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Caspase-8 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4790; RRID: AB_10545768 |

| Cleaved Caspase-8 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8592; RRID: AB_10891784 |

| Caspase-9 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9508; RRID: AB_2068620 |

| Caspase-3 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9662; RRID: AB_331439 |

| Caspase-7 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9492; RRID: AB_2228313 |

| Phospho-p38 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9211; RRID: AB_331641 |

| p38 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9212; RRID: AB_330713 |

| Phospho-JNK | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9255; RRID: AB_2307321 |

| JNK | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9252; RRID: AB_2250373 |

| Phospho-ERK1/2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4370; RRID: AB_2315112 |

| ERK1/2 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4695; RRID: AB_390779 |

| MMP12 | Invitrogen | Cat# PA5-86640; RRID: AB_2803407 |

| FOS | Invitrogen | Cat# MA5-36080; RRID: AB_2866692 |

| ADM | Invitrogen | Cat# PA5-36524; RRID: AB_2553571 |

| HSPA1A | Invitrogen | Cat# PA5-34772; RRID: AB_2552124 |

| CXCL9 | Invitrogen | Cat# PA5-81371; RRID: AB_2788585 |

| MMP3 | Invitrogen | Cat# PA527936; RRID: AB_2545412 |

| Peroxidase conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgG+IgM (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 115-035-068; RRID: AB_2338505 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG, human ads-HRP | Southern Biotech | Cat# 1030-05; RRID: AB_2619742 |

| Peroxidase AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 111-035-144; RRID: AB_2307391 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L-HRP | Abcam | Cat# ab6721; RRID: AB_955447 |

| GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2118; RRID: AB_561053 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Tumors isolated from beta-hCG transgenic mice | C57BL/6-/- × FVBbeta-hCG/- | N/A |

| Tumors isolated from beta-hCG transgenic mice-progesterone treated | C57BL/6 -/-× FVB beta-hCG/- | N/A |

| Tumors isolated from beta-hCG transgenic mice-vehicle treated | C57BL/6 -/-× FVB beta-hCG/- | N/A |

| Pituitaries | Murine | N/A |

| Ovaries | Murine | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| MTT | Invitrogen | Cat# M6494 |

| 3H-Thymidine | American Radiolabeled Chemicals | Cat# ART0178B |

| Annexin-V-PE | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556421 |

| DMEM High Glucose | Gibco | Cat# 12100046 |

| Antibiotic-antimycotic (100X) | Gibco | Cat# 15240062 |

| DMSO (For cell culture) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D2438 |

| Fetal bovine serum, qualified, Brazil | Gibco | Cat# 10270106 |

| Fetal bovine serum, EU Approved, charcoal treated | Himedia | Cat# RM10416 |

| StemPro™ Accutase™ cell dissociation reagent | Gibco | Cat# A1110501 |

| Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%), phenol red | Gibco | Cat# 25200056 |

| Mifepristone | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M8046 |

| Progesterone | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P8783 |

| Beta-Estradiol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# E2758 |

| Cholesterol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C3045 |

| Ethanol | Merck | Cat# 64-17-5 |

| hCG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C0434 |

| Native human beta-hCG | Abcam | Cat# ab126653 |

| Z-VAD-FMK | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 627610 |

| Tamoxifen | Enzo | Cat# ALX-550-095-G001 |

| Inhibitor JNK II | Calbiochem | Cat# 420119 |

| Inhibitor ERK_PD98059 | Calbiochem | Cat# 513000 |

| Inhibitor p38_SB203580 | Calbiochem | Cat# 559389 |

| RT-PCR FG-POWER SYBR GREEN PCR MASTER MIX | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 4367659 |

| 3B DNA Polymerase (5U/ul) with 10X reaction buffer (with 20 mM MgCl2) | 3bblackbio (Biotools) | Cat# 3B010 |

| DMSO (for analytical assays) | Amresco | Cat# 0231 |

| Propidium iodide | Invitrogen | Cat# P3566 |

| Annexin-V-FITC | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556419 |

| DMSO (Molecular biology grade) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D9170 |

| TRIzol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15596018 |

| Chloroform | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C2432 |

| 2-Propanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# I9516 |

| Nuclease-free water | Promega | Cat# P1197 |

| 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) | Calbiochem | Cat# 410957 |

| Ro-20-1724 | Calbiochem | Cat# 557502 |

| Annexin-V binding buffer | BD Biosciences | Cat# 51-66121E |

| DPX | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 06522 |

| Protease inhibitor | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32955 |

| Phosphatase inhibitor | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32957 |

| Nitrocellulose membrane | Bio-rad | Cat# 1620112 |

| Difco skimmed milk | BD Biosciences | Cat# 232100 |

| BSA | Merck | Cat# A7906 |

| ECL | Bio-rad | Cat# 1705061 |

| X-ray film | Carestream | Cat# 6568307 |

| Proteinase K | Qiagen | Cat# 1017738 |

| Iodogen | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 28600 |

| 3 color pre-stained protein ladder | Puregene (representative image in the raw data) | Cat# PG-PMT2922 |

| 100bp DNA ladder RTU | Gene Direx | Cat# DM001-R500 |

| RNAlater | Qiagen | Cat# 1018087 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| cAMP glo assay | Promega | Cat# V1501 |

| CellTiter Glo® luminescent cell viability assay (ATP assay) | Promega | Cat# G9242 |

| Mouse prolactin ELISA kit | R and D systems | Cat# DY1445 |

| Verso cDNA synthesis kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# AB1453A |

| Micro BCA protein assay kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 23235 |

| EnVision Flex+, mouse, high pH | Dako | Cat# K8002 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw and processed data for RNA-seq | This paper | GEO: GSE186999 |

| Raw data for agarose gels and Western blots | This paper | Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/46dvzxsbzs.1 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| LLC1 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1642 |

| A549 | ATCC | Cat# CCL-185 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| F1 non-transgenic and beta-hCG transgenic mice | C57BL/6-/-× FVBbeta-hCG/- | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Listed in Table S2 | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

| SigmaPlot 12.5 | SigmaPlot | SigmaPlot |

| Graph Pad Prism Version 8 | Graphpad-prism | Prism - GraphPad |

| ImageJ | ImageJ | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html |

| DAVID | DAVID | https://david.ncifcrf.gov/ |

| Flow Jo Version 10.8.1 | BD | FlowJo | FlowJo, LLC |

| "Quest Graph™ Four parameter logistic (4PL) curve calculator." AAT Bioquest, Inc, 13 Nov. 2021 | AAT Bioquest | https://www.aatbio.com/tools/four-parameter-logistic-4pl-curve-regression-online-calculator. |

| TCGA | N/A | Relevant links mentioned in STAR Methods |

| Primer-Blast | NCBI | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/ |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool | IDT | https://www.idtdna.com/pages/tools/oligoanalyzer |

| Jvenn | N/A | http://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/example.html |

| FastQC | Babraham Bioinformatics | http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ |

| Trimgalore | N/A | https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore |

| BioRender | BioRender.com | BioRender |

| Other | ||

| Thermo Scientific™ Nunc™ F96 microWell™ white polystyrene plate | Thermo Scientific | Cat# 136101 |

| Other common chemicals | Sigma/Merck | N/A |

| Cautery system | Gemini | Cat# GEM-5917 |

| Autoclip 9mm applier | Stoelting | Cat# 59043 |

| Autoclip remover | Stoelting | Cat# 59046 |

| Autoclips | Stoelting | Cat# 59047 |

| Mouse food pellets | Altromin International | Cat# 1314 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Rahul Pal (rahul@nii.ac.in).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new, unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell lines

LL/2 (LLC1) Lewis lung carcinoma cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-1642). They were originally isolated from a C57BL mouse bearing a spontaneous epidermoid carcinoma of the lung. These cells are derived from granular pneumocytes, equivalent to human alveolar cell carcinoma, and are highly tumorigenic. A549 human alveolar carcinoma cells were obtained from ATCC (CCL-185). They were originally isolated from the lung tissue of a 58-year-old Caucasian male with lung cancer.

Tumor cells were used within six months of purchase and resuscitation. Cells were maintained at 37o C in a 5% CO2 incubator in DMEM, high glucose (Gibco) supplemented with 3.7g/l sodium bicarbonate, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco), and 10% FBS (heat-inactivated); cultures were regularly checked for mycoplasma contamination. Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) was employed to dislodge cells for subculture. Prior to steroid treatment, cultures were maintained for an additional 24 h in the medium containing charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS, Himedia). Henceforth, this particular media formulation is referred to as serum-reduced media.

Mice

All animal studies were performed in compliance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. In addition, this study was carried out as per ARRIVE guidelines and in accordance with the recommendations of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India. Briefly, animals were housed in independently ventilated cages on a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle. Temperature was maintained at 21±2oC and humidity at 45-60%. Animals had access to food pellets (Altromin International) and water ad libitum. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Immunology (IAEC#528/19).

Eight-week old C57BL/6 female mice (procured from The Jackson Laboratory, USA) were outbred with eight-week old FVB male beta-hCG heterozygous transgenic mice, the latter a kind gift from Dr. Ilpo Huhtaniemi, Imperial College, UK; the transgenic mice express the beta-hCG transgene under the ubiquitin promoter. F1 female pups were weaned at 21 days and screened by genomic PCR for detection of the beta-hCG transgene and by radioimmunoassay for estimation of serum beta-hCG levels, as described below.

Method details

Cell viability

MTT

8 × 103 LLC1 tumor cells (12 × 103 for A549) were seeded onto 96 well plates for 6 h and after completion of respective treatments, the spent media was carefully removed from each well. 50 μl of 0.5 mg/ml MTT (Invitrogen) was added to cells for 1 h followed by 3 h incubation at 37°C with 100 μl DMSO (Amresco). The absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using Gen5 BioTek spectrometer. Reading of “blank” wells were subtracted from all values and percentage viability in comparison with relevant controls was calculated.

ATP measurement

16 × 103 LLC1 tumor cells were cultured in 24 well-plates for 8 h. Post completion of desired treatments, CellTiter-Glo® 2.0 Cell Viability Assay (PROMEGA) was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol with slight optimizations. Briefly, the plate and the commercial reagent to be added was equilibrated at 22°C for 15 min. The spent media was removed and the cells were washed with PBS. The pre-equilibrated reagent (provided with the kit) was reconstituted in serum-free DMEM in the ratio 1:1; this solution was added to each well, followed by an incubation for 2 min on a plate shaker. The plate was incubated at 22°C for an additional 10 min. The constituents of each well were collected and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at 4°C. The upper fraction was transferred into Thermo Scientific™ Nunc™ F96 MicroWell™ white polystyrene plates. Luminescence (indicative of cell viability) was measured using a Synergy H1 multimode plate reader. Percentage viability in comparison with relevant controls was calculated.

Cell proliferation

15 × 103 LLC1 tumor cells (20 × 103 for A549) were cultured in 96-well plates for 6 h. 18 h before completion of respective treatments, 0.5 μCi / 50 μl 3H-Thymidine (American Radiolabeled Chemicals) was added into each well. Cell-associated radioactivity was assessed on a beta-counter (Perkin Elmer).

Apoptosis

Flow cytometry

LLC1 tumor cells, cultured in 96-well plates, were treated with 100 μl accutase (Gibco) for 6 min to allow for gentle detachment of cells. 150 μl of serum-free DMEM was then added to each well. The constituents of each well were collected and centrifuged at 100 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The pellet was washed twice with cold PBS and reconstituted in 100 μl Annexin-V binding buffer (BD Biosciences). The constituents were transferred to FACS tubes and 5 μl PE-conjugated Annexin-V (BD Biosciences) was added to the samples. The tubes were subjected to gentle pulse vortexing to attain a single-cell suspension. The tubes were incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. The samples were reconstituted in 500 μl Annexin-V binding buffer and incubated for an additional 15 min. Samples were then analyzed by flow cytometry, after appropriate gating to avoid debris. FlowJo software was used for data analysis and the percentage of Annexin-V positive cells calculated.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

To enhance attachment of LLC1 tumor cells, coverslips were immersed in 1M HCl for 8 h, washed with water, immersed in 70% ethanol and then exposed to UV light for 20 min. Coverslips were placed in 24-well plates. 20 × 103 LLC1 tumor cells were then seeded, and cultured for 8 h. After completion of respective treatments, cells were washed with cold PBS. 200 μl Annexin-V binding buffer containing 7 μl FITC-conjugated Annexin-V (BD Biosciences) and 4 μl propidium iodide (100 μg/ml) (Invitrogen) were added to the wells. An incubation was carried out for 15 min followed by washes with cold Annexin-V binding buffer. DPX (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the mountant, and images were captured on a Carl Zeiss AxioImager Z1 microscope.

RNA extraction, semi-quantitative PCR and qPCR

Cells and tissues were lysed using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific); to attain complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes, the samples were allowed to stand for 5 min at room-temperature. 300 μl chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich) per ml TRIzol was added to the tubes. Samples were vigorously shaken and allowed to stand for 20 min at room temperature. The tubes were then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the upper aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube. 500 μl of 2-propanol (Sigma-Aldrich) per ml of TRIzol was added to the samples and the contents were gently mixed and allowed to stand for 15 min at room temperature. The tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed with 75% pre-chilled ethanol and dried at 60°C in a dry bath for 10 min. The ethanol-free pellet was dissolved in nuclease-free water (Promega). To assure complete dissolution of RNA, the tubes were placed in a dry bath at 65°C for 5 min. The RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically. cDNA was generated using the Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PRIMER-BLAST was employed for primer design and primers were assessed for quality using the OligoAnalyzerTM tool. Semi-quantitative PCR and qPCR were performed by using primers listed in Table S2. The enzyme 3B DNA Polymerase (Biotools) and FG-POWER SYBR GREEN PCR MASTER MIX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for semi-quantitative PCR and qPCR respectively. The ΔΔCt method was applied for quantification of relative mRNA levels.

cAMP assay

The cAMP glo assay kit (Promega) was employed; the manufacturer’s instructions were followed, with some modifications. Briefly, 16 × 103 LLC1 tumor cells were seeded onto 24-well plates for 8 h and were cultured for an additional 24 h in serum-reduced media. Cells were then incubated with serum-free media containing 500 μM IBMX (Calbiochem) and 100 μM Ro-20-1724 (Calbiochem) for 30 min to inhibit cellular phosphodiesterase. Test moieties were added in serum-free media; after completion of treatment, spent medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS. 150 μl of induction buffer (containing similar concentrations of IBMX and RO prepared in PBS) and 150 μl of lysis buffer was added to cells. To ensure complete lysis of cells, the plates were placed on a plate shaker for 20 min at room temperature. The constituents of each well were collected separately in tubes and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at 4°C. 40 μl of each supernatant was transferred into Thermo Scientific™ Nunc™ F96 MicroWell™ white polystyrene plate. Luminescence was measured using a Synergy H1 multimode plate reader. The concentration of cAMP was calculated using "Quest Graph™ Four Parameter Logistic (4PL) Curve Calculator.

Western blot

5 x 104 LLC1 tumor cells were seeded onto 6-well plates for 8 h, followed by an additional culture for 24 h in serum-reduced media. After completion of the respective treatments with test moieties, cells were lysed using 600 μl RIPA buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris Cl, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For MAPK detection, phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were additionally employed. To obtain efficient lysis, samples were incubated on ice for 20 min with occasional vortexing and were then sonicated at 4°C using Bioruptor Plus (Diagenode). Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and the total protein was estimated using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 35 μg (for MAPKs detection) and 40 μg (for caspase detection) of protein was loaded onto gels and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Biorad). The blots were “blocked” at room temperature for 3 h with 5% skimmed milk (BD Biosciences) in TBS (for caspase detection) and 5% BSA (Merck) in TBS (for MAPKs detection) followed by a 18 h incubation at 4°C with primary antibodies reconstituted in 5% skimmed milk in 0.1% TBST (for caspase detection) and 5% BSA in 0.1% TBST (for MAPKs detection). The blots were incubated for 1 h with HRP-labelled secondary antibodies at room temperature. Reactive moieties were visualized on X-ray film (Carestream) by enhanced chemiluminescence ECL (Biorad). Band intensities were calculated using ImageJ.

Genomic DNA isolation and PCR

Murine genomic DNA was isolated by the salting-out method. Briefly, tail clips of mice were collected and incubated in 300 μl digestion buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl; pH 7.5, 400 mM NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 0.6% SDS) containing 25 μl proteinase K (Qiagen) at 55°C in a dry bath for 8 h. 100 μl of 5.1 M NaCl was added and contents were mixed by inverting the tubes till the solution appeared milky. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 6 min and supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. To the clear supernatant, double volume of chilled 95% ethanol (Merck) was added and the contents were mixed gently. The samples were further incubated for 30 min at -20°C followed by centrifugation at 4°C for 20 min at 12,800 g. The pellet was washed thrice with 70% ethanol. Excess ethanol was evaporated by heating samples at 65°C for 10 min. The DNA was reconstituted in nuclease-free water and the samples were placed at 65°C for an additional 15 min to ensure complete dissolution of DNA. The quality of DNA was assessed spectrophotometrically. For detection of the beta-hCG transgene, PCR was carried out using 150 ng of DNA; primers are listed in Table S2. 3B DNA polymerase was employed, and 2% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the PCR master mix, owing to the primer’s high GC content.

Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

A Sephadex G-75 column (0.9 × 12 cm) was equilibrated with RIA buffer (0.125% NaH2PO4.H20, 0.6% Na2HPO4, 0.88% NaCl, 0.1 % NaN3, and 0.1% BSA; pH 7.4). Purified hCG (10,000 IU/mg) was labelled with Na125I by the Iodogen method. Briefly, 25 μl of 0.5 M PBS, hCG (5 μg/10 μl) and 1 mCi Na125I (Perkin Elmer) were added to a glass tube into which 5 μg iodogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific) had been previously adsorbed. After 10 min, the reaction mixture, along with 10 μl of 2% KI (Sigma-Aldrich), was transferred onto the G-75 column to separate iodinated hormone from free radioiodine. 0.5 ml fractions were collected and radioactivity was assessed on a gamma counter (Perkin Elmer). The first peak comprised radioactive iodinated hCG (125I-hCG) and the second peak of free 125I.

RIA was performed to quantify beta-hCG in sera derived from transgenic and non-transgenic mice. A murine monoclonal antibody (designated PIPP) was employed for this purpose. Diluted sera were incubated with an optimum concentration of PIPP, 100 μl of 20% normal horse serum and 125I-hCG (10,000 cpm, 40 μCi/μg) at 4°C for 16 h. 500 μl of 25% polyethylene glycol (Mw 8000; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to all tubes and a centrifugation was carried out at 600 g at 6°C for 20 min to precipitate immune complexes. Supernatants were decanted and radioactivity in the pellet was assessed on a gamma counter (Perkin Elmer). Pure hCG (1.25-40 ng/ml) was employed as a standard and serum beta-hCG was quantified by comparisons with the standard curve obtained upon linear regression.

Ovariectomy