Abstract

Background

This post hoc subgroup analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of eptinezumab for migraine prevention in patients with migraine and self-reported aura.

Methods

PROMISE-1 (NCT02559895; episodic migraine) and PROMISE-2 (NCT02974153; chronic migraine) were randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that evaluated eptinezumab for migraine prevention. In both studies, the primary outcome was the mean change from baseline in monthly migraine days over Weeks 1–12. Patients in this analysis included those who self-reported migraine with aura at screening.

Results

Of patients with episodic migraine, ∼75% reported a history of aura at screening; of patients with chronic migraine, ∼35% reported a history of aura. Changes in monthly migraine days over Weeks 1–12 were –4.0 (100 mg) and –4.2 (300 mg) with eptinezumab versus –3.1 with placebo in patients with episodic migraine with aura, and were –7.1 (100 mg) and –7.6 (300 mg) with eptinezumab versus –6.0 with placebo in patients with chronic migraine with aura. Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported by 56.0% (100 mg), 57.4% (300 mg), and 55.4% (placebo) of patients.

Conclusions

The preventive migraine efficacy of eptinezumab in patients in the PROMISE studies who self-reported aura was comparable to the overall study populations, demonstrating a similarly favorable safety and tolerability profile.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02559895 and NCT02974153

Keywords: Eptinezumab, migraine with aura, migraine prevention, efficacy

Introduction

Migraine with aura is a distinct diagnosis characterized by the presence of one or more fully reversible focal neurologic symptoms (Table 1), which are usually followed by headache and associated migraine symptoms (1,2). Most patients with migraine with aura report visual disturbances, such as visual scintillations and scotoma, that spread gradually over ≥5 minutes, last 5‒60 minutes, and precede headache onset within 60 minutes. Migraine with aura reportedly comprises approximately one-third of all migraine diagnoses (3) and has been associated with increased risk of cerebro- and cardiovascular disease (4,5).

Table 1.

Migraine with aura diagnostic criteria (2).

| A. | At least two attacks fulfilling criteria B and C |

| B. | One or more of the following fully reversible aura symptoms: |

| 1 visual | |

| 2 sensory | |

| 3 speech and/or language | |

| 4 motor | |

| 5 brainstem | |

| 6 retinal | |

| C. | At least three of the following six characteristics: |

| 1 at least one aura symptom spreads gradually over ≥5 minutes | |

| 2 two or more aura symptoms occur in succession | |

| 3 each individual aura symptom lasts 5–60 minutesa | |

| 4 at least one aura symptom is unilateralb | |

| 5 at least one aura symptom is positivec | |

| 6 the aura is accompanied, or followed within 60 minutes, by headache | |

| D. | Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

Reproduced with permission of International Headache Society (2).aWhen, for example, three symptoms occur during an aura, the acceptable maximal duration is 3 × 60 minutes. Motor symptoms may last up to 72 hours.

bAphasia is always regarded as a unilateral symptom; dysarthria may or may not be.

cScintillations and pins and needles are positive symptoms of aura.

ICHD-3, The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition.

Eptinezumab is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody specific for calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and is indicated for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults (6). In the pivotal PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 trials, eptinezumab 100 mg and 300 mg, the approved dose levels, met the primary efficacy endpoint; that is, they statistically significantly reduced mean monthly migraine days (MMDs) over Weeks 1–12 in patients with migraine, with sustained efficacy occurring as early as Day 1 after infusion (7–9). Given the high prevalence of migraine with aura, the associated medical risks, and the scarcity of published data specific to this population, we conducted a post hoc subgroup analysis of pooled data from the PROMISE trials to assess the efficacy and safety of eptinezumab for the preventive treatment of migraine in patients who self-reported a history of aura, potentially in addition to their migraines without aura.

Methods

The full methodologies of PROMISE-1 (NCT02559895) and PROMISE-2 (NCT02974153) have been published (8–11); key elements are reviewed here. Both studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all applicable local regulatory requirements. Independent ethics committee or institutional review board approval was obtained for each study site, with all patients providing written informed consent prior to study participation.

Both studies were phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials that evaluated the preventive efficacy, tolerability, and safety of eptinezumab in adults with migraine (8,9). PROMISE-1 enrolled patients with episodic migraine (EM) and PROMISE-2 enrolled patients with chronic migraine (CM). Migraine was defined using the International Classification for Headache Disorders (ICHD) definitions for migraine broadly (12,13). Patients separately reported any experience of aura with their migraine, being asked if they experience aura at the screening visit (and if it was ever experienced without headache pain). To improve the accuracy of self-reporting, investigators confirmed each patient’s understanding of aura during the screening visit and provided additional description and/or explanation, if needed. Educational materials pertaining to aura were also provided as part of electronic Diary (eDiary) training. The guide for investigators when discussing aura with patients included the following points of education, which were in alignment with ICHD criteria (Table 1): (a) Aura may affect vision, senses, speech or language, movement, and balance; (b) Sometimes an aura symptom may be followed by a second or third symptom of aura; (c) The symptoms may sometimes begin on one side of the head or body; (d) Each aura symptom may last anywhere from 5 minutes to an hour or more; (e) When the aura is related to a migraine, the migraine headache usually occurs within an hour of the aura. Visual aura was described as when vision is disturbed by bright, shimmering jagged or zigzag lines that spread, altering more and more in the field of vision. Additional symptoms of migraine with aura that were described included the sensation of pins and needles spreading slowly from one spot on one side of the body, face and/or tongue, which may be followed by numbness, as well as numbness without the pins and needles sensation and sensitivity, and trouble speaking or muscle weakness, clumsiness, or difficulty walking. Patients were told that these symptoms tend to happen about an hour before the start of a migraine but can vary.

Patients were randomized to receive eptinezumab 30 mg (PROMISE-1 only), 100 mg, 300 mg, or placebo administered intravenously every 12 weeks. Patients in PROMISE-1 received up to four treatments (48 weeks). Patients in PROMISE-2 received up to two treatments (24 weeks).

This post hoc analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of eptinezumab for the preventive treatment of migraine in the subgroup of patients who self-reported a history of aura at screening in either study. It included only those patients who received approved eptinezumab dose levels (i.e. 100 mg or 300 mg) (6) or placebo. Outcome measures included changes in migraine frequency (i.e. MMDs), migraine responder rates (≥50% and ≥75%) over Weeks 1–12 and 13–24, percent of migraine attacks with aura, acute medication days, and treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). Patients from PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 were pooled for all analyses except for the change from baseline in MMDs due to the differences in patient populations at baseline.

Monthly migraine days were derived from eDiary data and were based on 4-week intervals. A 50% responder was a patient who achieved a ≥50% reduction in MMDs, and a 75% responder was a patient who achieved a ≥75% reduction in MMDs. These reductions were evaluated by comparing the baseline frequency of migraine days to the migraine frequency in 4-week intervals. Results from the 4-week intervals were combined to produce 12- and 24-week responder endpoints.

In the daily eDiaries, patients indicated whether they experienced aura symptoms as discussed with the investigator during screening with their headache/migraine, which was used to determine the percentage of migraine attacks with aura. Available data from the 4-week intervals was combined to produce an average over 12 weeks. Patients with no migraine during a study were counted as a percentage of zero, and there was no missing data imputation for missing eDiary assessments.

Acute headache medication days were defined as the number of days within 4-week intervals where patients with migraine and a self-reported history of aura used acute headache medication (e.g. combination analgesics, ergotamine, opioids, simple analgesics, and triptans). Days of acute headache medication use were calculated as “any use” and “total use”. For “any use”, a day was counted if the patient took any acute medication. For “total use”, if multiple drug classes were taken on a single day, each drug class counted toward an acute medication day (e.g. if a patient used two drug classes in a single day, it counted as 2 days of medication use). Acute headache medication days of use were summarized in 4-, 12-, and 24-week intervals. The 12- and 24-week results were calculated as the average of the individual 4-week results that made up the wider intervals (e.g. Weeks 1–12 was calculated as the average of the Weeks 1–4, 5–8, and 9–12 results). The change from baseline for these measures was the difference between the baseline and the postbaseline interval.

For the efficacy analyses, patient results were summarized within the treatment group to which they were randomly assigned. For the safety analyses, patients were analyzed according to the randomized treatment they received.

Results

A total of 1741 patients received eptinezumab 100 mg, 300 mg, or placebo in PROMISE-1 or PROMISE-2. During the initial patient screening, 877 of these patients (50.4%) reported a history of experiencing aura, including 583/1153 (50.6%) patients who received eptinezumab (100 mg, n = 282; 300 mg, n = 301) and 294/588 (49.2%) patients who received placebo. Of patients with EM in PROMISE-1, ∼75% reported a history of experiencing aura at screening (100 mg, 167/221, 75.6%; 300 mg, 173/222, 77.9%; placebo, 167/222, 75.2%), and of patients with CM in PROMISE-2, ∼35% reported a history of experiencing aura at screening (100 mg, 115/356, 32.3%; 300 mg, 128/350, 36.6%; placebo, 127/366, 34.7%).

Demographics and baseline characteristics of this subpopulation with aura (PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 pooled) are summarized in Table 2. Treatment groups (eptinezumab 100 mg, eptinezumab 300 mg, and placebo) were well matched with regard to baseline characteristics. The mean age of all patients in this pooled analysis was 40.0 years, with the majority being female (761/877 [86.8%]) and white (751/877 [85.6%]). There were more patients with EM (507/877 [57.8%]) than with CM (370/877 [42.2%]) in this subgroup.

Table 2.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients with migraine and self-reported history of aura (PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 pooled efficacy population).

| Eptinezumab 100 mg (N = 282) | Eptinezumab 300 mg (N = 301) | Placebo (N = 294) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 40.1 (10.91) | 40.4 (11.08) | 39.5 (10.99) |

| Sex: Female, n (%) | 237 (84.0) | 269 (89.4) | 255 (86.7) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 250 (88.7) | 261 (86.7) | 240 (81.6) |

| Black or African American | 22 (7.8) | 30 (10.0) | 43 (14.6) |

| Other | 10 (3.5) | 10 (3.3) | 11 (3.7) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 28.7 (6.87) | 27.9 (6.06) | 28.8 (6.64) |

| Episodic or chronic migraine, n (%) | |||

| Episodic | 167 (59.2) | 173 (57.5) | 167 (56.8) |

| Chronic | 115 (40.8) | 128 (42.5) | 127 (43.2) |

| Mean age at diagnosis, years (SD) | 22.4 (10.99) | 21.7 (9.70) | 22.4 (10.30) |

| Mean duration of migraine diagnosis, years (SD) | 17.6 (11.24) | 18.8 (11.77) | 17.1 (11.24) |

| Mean duration of chronic migraine, years (SD) | 14.0 (11.08) | 15.5 (12.40) | 14.4 (11.95) |

| Mean baseline migraine days (SD) | 11.8 (4.98) | 11.9 (5.33) | 12.0 (5.40) |

| Mean baseline headache days (SD) | 14.4 (5.85) | 14.6 (5.97) | 14.7 (6.13) |

| Medication-overuse headache diagnosis, n (%) | 45 (16.0) | 50 (16.6) | 44 (15.0) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension-related | 16 (5.7) | 10 (3.3) | 10 (3.4) |

| Hyperlipidemia-related | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Diabetes-related | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Prior history of ischemic CV events/procedures | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 110 (39.0) | 94 (31.2) | 111 (37.8) |

| Male and ≥45 years | 18 (6.4) | 7 (2.3) | 11 (3.7) |

| Female and ≥55 years | 27 (9.6) | 32 (10.6) | 21 (7.1) |

| Race: Black or African American | 22 (7.8) | 30 (10.0) | 43 (14.6) |

| ≥1 CV risk factor | 157 (55.7) | 138 (45.8) | 152 (51.7) |

| ≥2 CV risk factors | 33 (11.7) | 34 (11.3) | 40 (13.6) |

BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; SD, standard deviation.

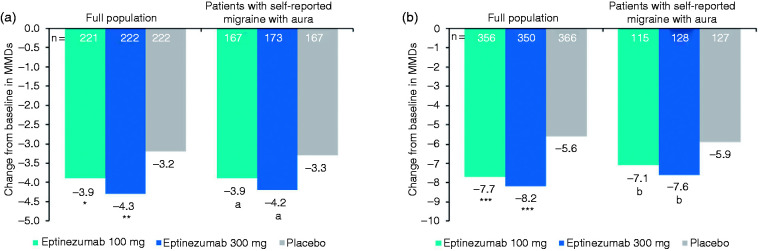

In each study, improvements in migraine frequency (i.e. MMDs) in patients reporting a history of aura were comparable to improvements in the total population (Figure 1). Patients with EM who received eptinezumab experienced approximately 4 fewer MMDs over Weeks 1–12 versus baseline regardless of self-reported history of aura, and patients with CM (with or without self-reported history of aura) who received eptinezumab experienced 7 to 8 fewer MMDs versus baseline over this time period. In each study, improvements in MMDs observed in the placebo group were similar in the subgroup of patients with self-reported history of aura (‒3.3 [EM] and ‒5.9 [CM] MMDs) and in the total population (‒3.2 [EM] and ‒5.6 [CM] MMDs).

Figure 1.

Mean change from baseline in MMDs over Weeks 1‒12 in the full study population and subgroup of patients with self-reported history of aura in (a) PROMISE-1 and (b) PROMISE-2.Differences between treatment groups were analyzed using an analysis of covariance model with change from baseline as the response variable and treatment and baseline migraine days as independent variables. MMD, monthly migraine days.*P = 0.0182; **P = 0.0001; ***P < 0.0001 vs. placebo (prespecified statistical testing).aTreatment difference vs. placebo (95% confidence interval) in change from baseline: 100 mg, −0.5 (−1.2, 0.2); 300 mg, −0.9(−1.5, −0.2).bTreatment difference vs. placebo (95% confidence interval) in change from baseline: 100 mg, −1.3 (−2.7, 0.2); 300 mg,−1.7 (−3.1, −0.3).

In the pooled group of patients reporting a history of aura, 51.4% and 56.1% of patients who received eptinezumab 100 mg or 300 mg, respectively, were ≥50% migraine responders (vs. 39% of patients who received placebo) and 22.3% and 27.2% of patients, respectively, were ≥75% migraine responders (vs. 18% of patients who received placebo) over Weeks 1–12 (Figure 2). Similarly, 54.6% (100 mg) and 59.4% (300 mg) of the total pooled PROMISE-1 or PROMISE-2 population who received eptinezumab were ≥50% migraine responders (vs. 38.6% of patients who received placebo), and 25.0% (100 mg) and 31.8% (300 mg) were ≥75% migraine responders (vs. 15.5% of patients who received placebo) over this same time period.

Figure 2.

Migraine responder rates over Weeks 1–12 in patients with migraine and self-reported history of aura (PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 pooled efficacy population).Δ? placebo, difference from placebo (95% confidence interval). MRR, migraine responder rate.

At baseline, the percentage of migraine attacks with aura was 33.6% with eptinezumab 100 mg, 36.0% with eptinezumab 300 mg, and 33.8% with placebo. The change from baseline over Weeks 1–12 in percentage of migraine attacks with aura was numerically greater with eptinezumab than placebo, decreasing to 28.7% (100 mg, mean change: −5.0 percentage points), 31.4% (300 mg, mean change: −4.7 percentage points), and 30.6% (placebo, mean change: −3.1 percentage points).

Reductions in acute headache medication use from baseline over Weeks 1–12 were larger with eptinezumab than with placebo for any medication use (Figure 3; a single day was only counted once regardless of the use of multiple drug classes) and for total medication use (Supplementary Figure 1; if multiple drug classes were used on a single day, the use was counted more than once). Patients who received eptinezumab experienced approximately 4 fewer medication days (100 mg and 300 mg, ‒3.9 days) each month over Weeks 1–12 versus 3 fewer monthly medication days (‒2.9 days) in the placebo group. Over Weeks 1‒12, the mean monthly acute medication use was 5.4 days, 6.4 days, and 7.2 days for eptinezumab 100 mg, 300 mg, and placebo, respectively.

Figure 3.

Mean “any” acute headache medication days per month in patients with migraine and self-reported history of auraa (PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 pooled efficacy population).Acute headache medications (AHM) included combination analgesics, ergotamine, opioids, simple analgesics, and triptans.aIf multiple drug classes were taken on a single day, the day was counted once.

Treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar across treatment groups in patients with self-reported aura (100 mg, 56.0%; 300 mg, 57.4%; placebo, 55.4%; Table 3). The most common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis (65/881, 7.4%) and upper respiratory tract infection (65/881, 7.4%). Cardiac disorders occurred infrequently (100 mg, 3/284, 1.1%; 300 mg, 3/303, 1.0%; placebo, 2/294, 0.7%), as did vascular disorders (100 mg, 5/284, 1.8%; 300 mg, 4/303, 1.3%; placebo, 2/294, 0.7%). Increased blood pressure occurred in <2% of patients in any treatment group (100 mg, 5/284, 1.8%; 300 mg, 3/303, 1.0%; placebo, 2/294, 0.7%).

Table 3.

Summary of TEAEs in patients with migraine and self-reported history of aura (PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 pooled safety populations).

| Eptinezumab 100 mg (N = 284) | Eptinezumab 300 mg (N = 303) | Placebo (N = 294) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with any TEAE, n (%)/Total number of events | 159 (56.0)/429 | 174 (57.4)/435 | 163 (55.4)/413 |

| Most common TEAEs (≥2% of patients total), n (%) | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 25 (8.8) | 23 (7.6) | 17 (5.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 19 (6.7) | 29 (9.6) | 17 (5.8) |

| Sinusitis | 9 (3.2) | 13 (4.3) | 15 (5.1) |

| Nausea | 6 (2.1) | 7 (2.3) | 10 (3.4) |

| Bronchitis | 5 (1.8) | 8 (2.6) | 9 (3.1) |

| Dizziness | 8 (2.8) | 5 (1.7) | 9 (3.1) |

| Back pain | 10 (3.5) | 5 (1.7) | 7 (2.4) |

| Fatigue | 8 (2.8) | 10 (3.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Influenza | 3 (1.1) | 10 (3.3) | 7 (2.4) |

| Migraine | 3 (1.1) | 7 (2.3) | 9 (3.1) |

| Arthralgia | 4 (1.4) | 7 (2.3) | 8 (2.7) |

| Patients with any TEAE leading to treatment discontinuation, n (%) | 7 (2.5) | 3 (1.0) | 5 (1.7) |

| Patients with any TEAE related to study drug, n (%) | 37 (13.0) | 49 (16.2) | 27 (9.2) |

| Patients with any TEAE by maximum severity, n (%) | |||

| Mild | 64 (22.5) | 71 (23.4) | 60 (20.4) |

| Moderate | 87 (30.6) | 93 (30.7) | 91 (31.0) |

| Severe | 8 (2.8) | 10 (3.3) | 11 (3.7) |

| Life-threatening | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Patients with serious TEAEs (≥2 patients), n (%) | 6 (2.1) | 5 (1.7) | 7 (2.4) |

| Syncope | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (0.7) |

| Migraine | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Suicide attempt | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Most TEAEs in patients with migraine and self-reported aura were mild or moderate in severity. TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 15 patients (100 mg, n = 7, 2.5%; 300 mg, n = 3, 1.0%; placebo, n = 5, 1.7%; Table 3). Serious TEAEs occurred in 18 patients (100 mg, n = 6, 2.1%; 300 mg, n = 5, 1.7%; placebo, n = 7, 2.4%). Compared to the established safety and tolerability profile of eptinezumab (8,9,14), no new safety signals were identified specifically in this subgroup of patients self-reporting a history of aura.

Discussion

In this subgroup analysis of patients with migraine and a self-reported history of aura, efficacy results were consistent with the full population results of PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2, with patients experiencing reductions in migraine frequency (4 [EM] to 8 [CM] fewer MMDs vs. baseline), proportion of migraine attacks with aura (decrease from baseline of ∼5 percentage points), and acute medication use (4 fewer acute medications days per month). Also, the tolerability profile of eptinezumab in patients with migraine and self-reported history of aura was consistent with what was previously reported in the full EM and CM populations. These findings suggest that eptinezumab may be clinically useful in the migraine with aura subpopulation.

Eptinezumab decreased the percentage of migraine attacks with aura relative to baseline (percentage-point decreases of 5.0 and 4.7) and to a larger extent than placebo (percentage-point decreases of 3.1), suggesting a small treatment effect on aura frequency beyond reducing migraine frequency. The effects of eptinezumab on the severity of aura and specific aura presentation were not specifically evaluated in the PROMISE studies, and only limited data with respect to effects on aura have been reported for the entire CGRP monoclonal antibody drug class. A single report of a post hoc analysis of data from three phase 3 clinical studies indicated that galcanezumab reduced both the frequency of prodromal symptoms relative to placebo (in patients with EM and with CM) and the number of migraine headache days with aura (significant in patients with EM only) but did not specifically evaluate the impact of treatment on aura or headache frequency in patients with a diagnosis or history of aura at baseline (15). Thus, there remains a need for additional prospective evaluations of the effects of these agents specifically in patients with aura.

Eptinezumab was well tolerated in the subgroup of patients with a self-reported history of aura. As in the full PROMISE populations, the most frequently reported TEAEs were upper respiratory tract infection and nasopharyngitis, with limited reports of increased blood pressure. There was no evidence of increased risk for cardiovascular adverse events, a potential concern for patients with aura. The low risk for cardiovascular adverse events reported here is consistent with that reported in a pooled analysis of data from five large-scale eptinezumab clinical trials, during which reports of cardiovascular adverse events among more than 2800 patients (who received doses of eptinezumab ranging from 30 mg to 1000 mg) were infrequent (14). Whereas approximately one-half of all patients in the subgroup of patients with a self-reported history of aura in the PROMISE studies had one or more cardiovascular risk factors at baseline (however, not all risk factors were measured, including history of tobacco use and family history), patients with significant cardiovascular disease were excluded from participation in these or any of the other large-scale eptinezumab trials. Thus, cardiovascular safety in patients with migraine with aura and significant cardiovascular comorbidities remains to be established.

The results of this post hoc analysis are limited by the method by which patients with aura were identified. The PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 studies included patients that fulfilled criteria for migraine with or without aura and were not designed to assess the efficacy and safety in patients diagnosed with migraine with aura specifically. Therefore, the ICHD definition of migraine with aura was not used for formal diagnosis; rather, the study relied on patient acknowledgement of aura as to whether their symptoms fulfilled aura (i.e. patients with aura for the purpose of these analyses were those who self-reported a history of aura at screening). Although patient training on aura was based on ICHD criteria, the method to capture aura did not allow for analysis of patients with a formal, ICHD-based diagnosis of migraine with aura. Whereas the 50% prevalence of aura self-reported herein (and the 76.2% prevalence of aura self-reported in PROMISE-1 [EM patients]) is higher than the 30% aura prevalence generally cited for migraine, it is well within the range of patients with migraine reporting premonitory symptoms in the clinical setting (38%‒87%) (16–22) and is consistent with recent studies on erenumab and galcanezumab (23,24). It is notable that high rates of premonitory symptoms have been described in patients with a diagnosis of migraine with aura as well as in those with a diagnosis of migraine without aura (16,18). Thus, the presence of premonitory symptoms in patients without a specific migraine with aura diagnosis is not unusual, and questioning and discussion regarding these symptoms should be a part of the clinical evaluation for all migraine patients. The high rate of aura in PROMISE-1 may be due to selection bias reflective of the misunderstanding that sometimes occurs with aura (i.e. the difference between having visual symptoms and being diagnosed with migraine with aura) that may have caused the sites to over-classify patients into this aura group. Additionally, changes in aura beyond incidence/frequency were not collected or monitored throughout the study to determine if eptinezumab affects aura severity or type. Lastly, this was a post hoc analysis; as such, the limitations are widely recognized. Additional prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusion

In this post hoc subgroup analysis, eptinezumab demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in patients with migraine and self-reported history of aura, consistent with full study population results. Although further research is warranted, these findings suggest that eptinezumab treatment may be clinically useful in this subpopulation of patients with migraine.

Article Highlights

In patients with episodic or chronic migraine and self-reported history of migraine with aura, eptinezumab demonstrated efficacy and tolerability consistent with the full study populations.

There was no evidence of increased risk for cardiovascular adverse events, a potential concern for patients with aura.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_03331024221077646 for Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with migraine and self-reported aura: Post hoc analysis of PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 by Messoud Ashina, Peter McAllister, Roger Cady, Joe Hirman and Anders Ettrup in Cephalalgia

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Tom, PharmD, and Nicole Coolbaugh, CMPP, of The Medicine Group (New Hope, PA, USA), for providing medical writing support, which was funded by H. Lundbeck A/S in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Footnotes

Author contributions: MA, PM, RC, and AE contributed to the conception and design of the study or data acquisition. JH performed the statistical analyses, and all authors contributed to interpretation of the data. All authors reviewed and provided critical revision of all manuscript drafts for important intellectual content, as well as read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Data availability: In accordance with EFPIA’s and PhRMA’s “Principles for Responsible Clinical Trial Data Sharing” guidelines, Lundbeck is committed to responsible sharing of clinical trial data in a manner that is consistent with safeguarding the privacy of patients, respecting the integrity of national regulatory systems, and protecting the intellectual property of the sponsor. The protection of intellectual property ensures continued research and innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. Deidentified data are available to those whose request has been reviewed and approved through an application submitted to https://www.lundbeck.com/global/our-science/clinical-data-sharing.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MA is a consultant, speaker, or scientific advisor for AbbVie/Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Teva; primary investigator for AbbVie/Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Lundbeck ongoing trials. MA has no ownership interest and does not own stocks of any pharmaceutical company. MA serves as associate editor of Cephalalgia, associate editor of the Journal of Headache and Pain, and associate editor of Brain.

PM reports receiving personal fees and research support from AbbVie, Amgen/Novartis, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, and Teva.

RC was an employee at Lundbeck or one of its subsidiary companies at the time of the study and manuscript development.

JH is an employee of Pacific Northwest Statistical Consulting, Inc., a contracted service provider of biostatistical resources for H. Lundbeck A/S.

AE is an employee of H. Lundbeck A/S.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The clinical trial was funded by Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA. The publication was supported by H. Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Ashina M. Migraine. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1866–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lipton RB, Scher AI, Kolodner K, et al. Migraine in the United States: epidemiology and patterns of health care use. Neurology 2002; 58: 885–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurth T, Rist PM, Ridker PM, et al. Association of migraine with aura and other risk factors with incident cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 2020; 323: 2281–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahmoud AN, Mentias A, Elgendy AY, et al. Migraine and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: a meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies including 1 152 407 subjects. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e020498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.VYEPTI [package insert]. Bothell, WA: Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals, Inc., 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodick DW, Gottschalk C, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab demonstrated efficacy in sustained prevention of episodic and chronic migraine beginning on Day 1 after dosing. Headache 2020; 60: 2220–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashina M, Saper J, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia 2020; 40: 241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Smith J, et al. Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine. PROMISE-2. Neurology 2020; 94: e1365–e1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TR, Janelidze M, Chakhava G, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: sustained effect through 1 year of treatment in the PROMISE-1 study. Clin Ther 2020; 42: 2254–2265.e2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silberstein S, Diamond M, Hindiyeh NA, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of chronic migraine: efficacy and safety through 24 weeks of treatment in the phase 3 PROMISE-2 (Prevention of migraine via intravenous ALD403 safety and efficacy–2) study. J Headache Pain 2020; 21: 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 Suppl 1: 9–160. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 629-808. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Smith TR, Spierings ELH, Cady R, et al. Safety and tolerability of eptinezumab in patients with migraine: a pooled analysis of 5 clinical trials. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ament M, Day K, Stauffer VL, et al. Effect of galcanezumab on severity and symptoms of migraine in phase 3 trials in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoonman GG, Evers DJ, Terwindt GM, et al. The prevalence of premonitory symptoms in migraine: a questionnaire study in 461 patients. Cephalalgia 2006; 26: 1209–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quintela E, Castillo J, Muñoz P, et al. Premonitory and resolution symptoms in migraine: a prospective study in 100 unselected patients. Cephalalgia 2006; 26: 1051–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurell K, Artto V, Bendtsen L, et al. Premonitory symptoms in migraine: A cross-sectional study in 2714 persons. Cephalalgia 2016; 36: 951–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen BK, Olesen J. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura: an epidemiological study. Cephalalgia 1992; 12: 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amery WK, Waelkens J, Vandenbergh V. Migraine warnings. Headache 1986; 26: 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelman L. The premonitory symptoms (prodrome): a tertiary care study of 893 migraineurs. Headache 2004; 44: 865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santoro G, Bernasconi F, Sessa F, et al. Premonitory symptoms in migraine without aura: a clinical investigation. Funct Neurol 1990; 5: 339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAllister P, Gomez JP, McGill L, et al . Efficacy of erenumab for the treatment of patients with episodic migraine with aura (P4.094). Neurology 2018; 90: P4.094. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulleners WM, Kim BK, Láinez MJA, et al. Safety and efficacy of galcanezumab in patients for whom previous migraine preventive medication from two to four categories had failed (CONQUER): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Neurol 2020; 19: 814–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_03331024221077646 for Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with migraine and self-reported aura: Post hoc analysis of PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2 by Messoud Ashina, Peter McAllister, Roger Cady, Joe Hirman and Anders Ettrup in Cephalalgia