Abstract

Highlight:

This is the first systematic review to investigate non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder.

Background:

Psychotherapy is the recommended treatment for borderline personality disorder. While systematic reviews have demonstrated the effectiveness of psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder, effect sizes remain small and influenced by bias. Furthermore, the proportion of people who do not respond to treatment is seldom reported or analysed.

Objective:

To obtain an informed estimate of the proportion of people who do not respond to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder.

Methods:

Systematic searches of five databases, PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library, occurred in November 2020. Inclusion criteria: participants diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, treated with psychotherapy and data reporting either (a) the proportion of the sample that experienced ‘reliable change’ or (b) the percentage of sample that no longer met criteria for borderline personality disorder at conclusion of therapy. Exclusion criteria: studies published prior to 1980 or not in English. Of the 19,517 studies identified, 28 met inclusion criteria.

Results:

Twenty-eight studies were included in the review comprising a total of 2436 participants. Average treatment duration was 11 months using well-known evidence-based approaches. Approximately half did not respond to treatment; M = 48.80% (SD = 22.77).

Limitations:

Data regarding within sample variability and non-response are seldom reported. Methods of reporting data on dosage and comorbidities were highly divergent which precluded the ability to conduct predictive analyses. Other limitations include lack of sensitivity analysis, and studies published in English only.

Conclusion:

Results of this review suggest that a large proportion of people are not responding to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder and that factors relating to non-response are both elusive and inconsistently reported. Novel, tailored or enhanced interventions are needed to improve outcomes for individuals not responding to current established treatments.

Keywords: Non-response, poor response, treatment failure, treatment outcomes, psychotherapy outcomes, borderline personality disorder

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a commonly occurring mental health disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Grant et al., 2008; Tyrer et al., 2010; Winsper et al., 2020). BPD can have severe and profound effects for people who live with the disorder and for those who care for them (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Grenyer et al., 2019; Leichsenring et al., 2011). BPD is known to be highly comorbid with mood, anxiety, substance use and other personality disorders; furthermore, it has been associated with high rates of self-harm, suicide and long-term psychosocial dysfunction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Broadbear et al., 2020; Pucker et al., 2019; Soloff and Chiappetta, 2019). Due to the characteristics of the disorder, and degree of comorbidity, BPD can be associated with extensive consumption of mental health resources (Bailey and Grenyer, 2014; Comtois et al., 2003; Hörz et al., 2010; Leichsenring et al., 2011).

In recent decades, multiple BPD-specific psychotherapies have been developed and tested, resulting in a stronger evidence base (Cristea et al., 2017; Storebø et al., 2020). Furthermore, clinical guidelines recommend psychotherapy as the treatment of choice for BPD (Grenyer et al., 2015; National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), 2012). Additionally, evidence-based psychological therapies for BPD have been shown to be less expensive and more effective than treatment as usual (Meuldijk et al., 2017). Accordingly, the prognosis for people living with the disorder has greatly improved (Grenyer, 2013). However, no treatment has yet consistently shown that it can lead to the remission of BPD for most consumers (Leichsenring et al., 2011), and many people with BPD continue to experience problems reaching healthy levels of social and occupational functioning, even after treatment (Zanarini et al., 2010).

The majority of research that evaluates treatment outcomes for BPD reports group statistics in the form of effect sizes. Although this methodology is useful as it enables cross study comparison, it does not allow for the investigation of treatment outcome variability within samples or reveal the proportion of participants who are not responding to treatment. Two reviews report longitudinal rates of remission. Ng et al.’s (2016) narrative synthesis reported that across 11 cohorts, who were followed for periods of 4–27 years, 33–99% of participants reached remission. Álvarez-Tomás et al. (2019) reported that across nine studies, who followed participants for up to 14 years, 50–70% of participants reached remission. Remission from BPD is typically defined as no longer meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria for BPD for 2 years (Zanarini et al., 2012). The results from these reviews indicate that remission from BPD is achievable and common for large proportions of individuals over longer periods of time. Additionally, and of equal importance, these results demonstrate that up to 50% of participants are not reaching remission (Álvarez-Tomás et al., 2019; Ng et al., 2016). However, as these reviews report results from long-term follow-up studies which examine remission across the lifespan, they do not reveal the percentage of people who do not respond to treatment by reducing their BPD symptoms. Compiling the proportion of people who do not reduce symptoms enough to no longer meet criteria or to have reliably changed their BPD symptoms post treatment is how the present research will operationalise non-response to psychotherapy for BPD.

To improve treatment outcomes for people with BPD, we need to thoroughly understand why some treatment consumers still experience significant challenges on their recovery journey. The first step in this task is to determine the proportion of people who do not respond to treatment. This study aims to obtain an informed estimate of the percentage of people who do not respond to psychotherapy for BPD by conducting a systematic review of studies that have reported treatment outcomes for psychotherapies used to treat BPD.

Materials and method

Protocol and registration

The current review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews (Liberati et al., 2009). The protocol was registered by the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42020147289).

Data sources

Literature was searched for relevant articles in November 2020 using the following online databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library. A unique search strategy was used for each database to ensure a comprehensive and inclusive search. The exact strategy for each database can be located in the Supplementary Material. Search terms used for each database included the following: ‘borderline personality disorder’ AND (effect OR effects OR effectiveness OR efficacy OR evidence OR outcome OR outcomes OR result OR results OR therapy OR therapies OR therapeutic OR psychotherapy OR psychotherapies OR psychotherapeutic OR treatment OR treatments OR intervention OR interventions OR comparison OR pilot OR trial OR feasibility OR randomized OR randomised OR longitudinal OR prospective OR ‘follow up’ OR training OR program OR respond OR response OR recover OR recovery OR recovered OR remission OR remitted OR remit OR ‘reliable change’ OR ‘clinically significant change’ OR ‘met criteria’ OR ‘meets criteria’). Search limiters included the year (1980–2020), English, Language, Academic Journals and Peer Reviewed.

Study selection

Studies were selected using a two-stage process: title and abstract screening and full-text assessment. Both stages were conducted independently by two authors (J.W. and S.S.; and then J.W. and M.T.). Both stages were undertaken using Covidence, an online systematic review management system (Veritas Health Innovation, 2021). The reference lists of three large reviews were also used as another source of studies (Cristea et al., 2017; Levy et al., 2018; Stoffers-Winterling et al., 2012) to ensure a thorough search of the literature, although none were included as they did not pass full-text screening stage. An additional study was found through correspondence with an author while seeking further data (Gregory et al., 2010), and this study was included as it met the review criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The research question was designed using the Participants, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) Framework (Schardt et al., 2007). Based on this framework, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Primary diagnosis of BPD as per DSM or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic classifications or a BPD-specific structured clinical interview. All ages, genders and comorbidities allowed.

Intervention

Any type of psychotherapy used for the treatment of BPD. Psychotherapy was defined as talk therapy using specific approaches as designed and manualised in the individual published research studies (i.e. dialectical behaviour therapy [DBT], schema-focused therapy [SFT], transference-focused psychotherapy [TFP], mentalisation-based therapy [MBT]) or a generalised approaches (i.e. general psychiatric management [GPM], treatment as usual [TAU], cognitive behaviour therapy [CBT], psychodynamic) provided by a mental health professional. Group or individual format allowed. Adjunct pharmacological therapy allowed. Possible inclusions: pilot studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), efficacy or effectiveness studies, and naturalistic studies.

Comparator group

Any comparator group allowed.

Outcomes

Individual outcomes in the form of either still meeting criteria for BPD or not having reached reliable change indices post treatment. Outcomes from any study design will be allowed, as long as the aim is to test the efficacy or effectiveness of psychotherapy for BPD.

Exclusion criteria

Participants

Any study whose participants do not meet full criteria for BPD. Any studies reporting on samples where less than 100% of participants met full criteria for BPD.

Interventions

Any study whose aim is to explore BPD as opposed to treat the disorder. Any study whose treatment aim is to reduce only certain sub-sets of BPD symptoms, or certain clinical characteristics of BPD, or who are receiving pharmacological treatments alone.

Comparator group

No exclusions.

Outcomes

Any studies who do not report percentages of samples who responded to treatment via reaching reliable change indices or no longer meeting diagnostic criteria. Any study that does not calculate reliable change indices based on BPD symptom-specific measures. Any study which collected outcome data up to 6 months post treatment cessation was included, due to the aim of the study being to focus on change in BPD criteria as a direct response to therapy, as opposed to a natural reduction in symptoms across time.

Further limiters

Studies published before 1980 will be excluded because the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed.; DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980) was the first DSM to include BPD as a diagnostic category. Studies published prior to the adoption of these diagnostic criteria used a definition of BPD that was too heterogeneous and not yet definitive (Gunderson, 2009; Gunderson and Singer, 1975). Any study not published in English.

Data extraction

Two authors (J.W. and S.R.) independently extracted data from the included studies. Data were initially collated into a data extraction spreadsheet, before being compiled into an SPSS document for analyses. Data extracted included country of publication, study characteristics (design, setting), sample characteristics (number of participants, age, gender, tool used for diagnosis, comorbidities, psychotropic medication use), treatment characteristics (type, dose, comparator, duration), and the main outcome; percentage not responded at the end of treatment and the method used to determine non-response.

Data analysis

There are two main ways that studies report the percentage of individuals that respond to treatment:

Reaching symptomatic remission: No longer meeting DSM/ICD criteria of end of treatment.

Demonstrating change in BPD symptomatology: Reaching criteria for reliable or clinically significant change indices.

The second definition of non-response is a common approach for determining change created by Jacobson and Truax (1991). This approach determines whether the change in the score is statistically and/or clinically significant and cannot be attributed to measurement error alone. To reach clinical significance, an individual’s score must be reliably changed and to have moved the participant from the clinical population range to the non-clinical population range.

The mean of the percentage of sample not responded will be reported as the main outcome of the review. This will be calculated by the review team by subtracting the values from 100. The mean of participants not responded will also be reported as weighted by sample size and treatment duration.

Results

Search results

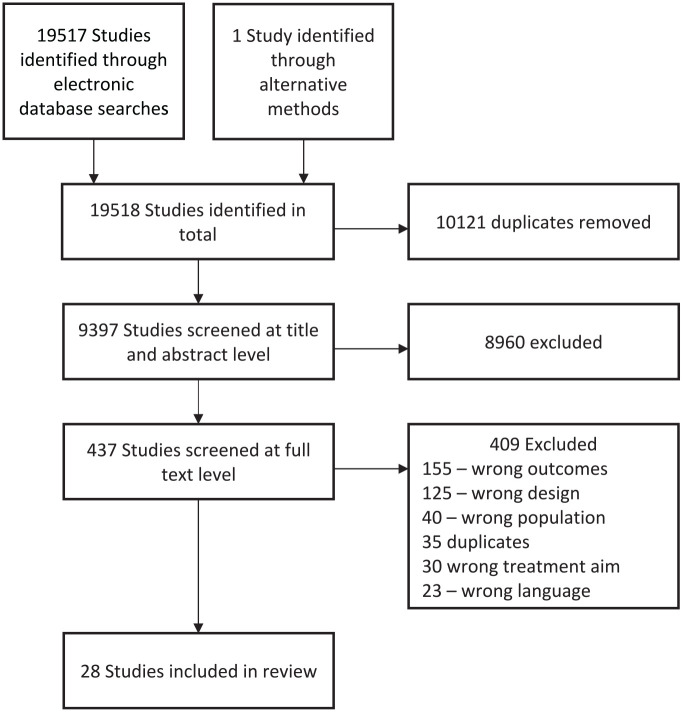

Searching the electronic databases resulted in the identification of 19,517 references. The PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1) shows the number of studies identified, screened and included. To ensure focus was maintained, the task of title and abstract screening was completed in 2-hour blocks.

Figure 1.

PRSIMA flow chart.

Critical appraisal

The quality of included studies was assessed using three Joanna Briggs Critical Appraisal Tools (Briggs, 2020). Each study was independently assessed by two authors (J.W. and S.R.). Each checklist includes up to 13 questions, which evaluate the quality of the study in terms of randomisation, methodology, reliability and appropriateness of statistical analyses. Each question can receive a ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’ answer. The number of ‘yes’ answers for the studies with RCT designs ranged from 8/13 to 11/13, M = 9.78 (SD = 1.30). For the studies with cohort designs, the ‘yes’ answers ranged from 2/8 to 8/8, M = 6.25 (SD = 2.03), and the for the studies with cross-sectional designs the ‘yes’ answers ranged from 7/11 to 9/11, M = 8.00 (SD = 1.00). The quality of the studies varied. However, the aim of this review is to gain an estimate of the proportion of people who are not responding to treatment received in both ‘controlled conditions’ (efficacy studies) and as it would be ‘received in the community’ (effectiveness studies of specialised or generalised treatments, for example, DBT or TAU) for greater generalisability. Therefore, all study designs and all levels of quality were included.

Excluded studies

The literature is abundant with many psychotherapy outcome studies for BPD. However, many of the initially identified studies were excluded at full-text screening stage due to not reporting the main outcome variable sought; individual response to psychotherapy as determined by reaching reliable change criteria (RCI) or no longer meeting diagnostic criteria (Arntz et al., 2015; Barnicot and Crawford, 2019; Bateman and Fonagy, 1999; Black et al., 2013; Bos et al., 2011; Chanen et al., 2009; Clarkin et al., 2007; Davidson et al., 2006; Gunderson et al., 2006; Linehan et al., 2006; McMain et al., 2009). Although these studies provide valuable information, group statistics were employed to report outcome results. Other studies used a design meaning they did not report outcomes specifically pertaining to BPD symptoms within 6 months of treatment cessation (Antonsen et al., 2017; Bateman and Fonagy, 2008; Bohus, 2008; Gregory et al., 2006; Kleindienst et al., 2008; McGlashan, 1986). Fewer were excluded for reporting on a diffuse population; thorough standardised diagnostics were not employed or 100% of the sample did not meet full criteria for BPD (Moran et al., 2018; Morton et al., 2012; Tucker et al., 1987) or were excluded for a diffuse treatment aim; the focus of the outcomes reported was not on BPD criteria (Fertuck et al., 2012; Gratz et al., 2015).

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 1. Of the 28 included studies, 8 were RCTs. The remaining 20 included naturalistic uncontrolled efficacy and effectiveness studies, further analyses of previous RCTs, and pilot studies. The majority of the studies were set in the community (26) and 2 were conducted in inpatients settings. Pertaining to countries, 11 studies took place in America, 4 in the United Kingdom, 3 in The Netherlands, 2 in Germany, 2 in Australia, 1 each for the countries of Italy, Spain, Sweden, Denmark and Norway, while 1 was conducted in both Germany and Austria.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Study number | Author and date | Psychotherapy | Country | Study design | Setting | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bateman and Fonagy (2013) | MBT and SCM | UK | Further analyses of results from an earlier randomised controlled trial | Community | Impact of Clinical Severity on Outcomes of Mentalisation-Based Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder |

| 2 | Bellino et al. (2010) | IPT-BPD + fluoxetine | Italy | Randomised controlled trial | Community | Adaptation of Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Borderline Personality Disorder: A Comparison of Combined Therapy and Single Pharmacotherapy |

| 3 | Blennerhasset et al. (2009) | DBT | UK | Naturalistic uncontrolled efficacy study | Community | Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in an Irish Community Mental Health Setting |

| 4 | Blum et al. (2002) | STEPPS | America | Pilot study | Community | STEPPS: A Cognitive-Behavioral Systems-Based Group Treatment for Outpatients with Borderline Personality Disorder – A Preliminary Report |

| 5 | Brown et al. (2004) | CT | America | Uncontrolled clinical trial | Community | An Open Clinical Trial of Cognitive Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder |

| 6 | Dickhaut and Arntz (2014) | SFT with trained and untrained facilitators | The Netherlands | Efficacy study | Community | Combined Group and Individual Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pilot Study |

| 7 | Dixon-Gordon et al. (2015) | DBT-ER, DBT-IE and a Psychoeducation control group | America | Pilot study | Community | A Preliminary Pilot Study Comparing Dialectical Behavior Therapy Emotion Regulation Skills with Interpersonal Effectiveness Skills and a Control Group Treatment |

| 8 | Doering et al. (2010) | TFP and TAU | Germany and Austria | Randomised controlled trial | Community | Transference-Focused Psychotherapy V. Treatment by Community Psychotherapists for Borderline Personality Disorder: Randomised Controlled Trial |

| 9 | Elices et al. (2016) | DBT-M and DBT-IE | Spain | Randomised controlled trial | Community | Impact of Mindfulness Training on Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Trial |

| 10 | Farrell et al. (2009) | SFT-G + TAU and TAU | America | Randomised controlled trial | Community | A Schema-Focused Approach to Group Psychotherapy for Outpatients with Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial |

| 11 | Giesen-Bloo et al. (2006) | SFT and TFP | The Netherlands | Randomised controlled trial | Community | Outpatient Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder: Randomized Trial Of Schema-Focused Therapy Vs Transference-Focused Psychotherapy |

| 12 | Gratz and Gunderson (2006) | ERG + TAU | America | Efficacy study | Community | Preliminary Data on an Acceptance-Based Emotion Regulation Group Intervention for Deliberate Self-Harm Among Women with Borderline Personality Disorder |

| 13 | Gregory et al. (2010) | DDP and TAU | America | Randomised controlled trial | Community | Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder Comorbid with Alcohol Use Disorders: 30-Month Follow-Up |

| 14 | Gregory and Sachdeva (2016) | DDP, DBT and TAU | America | Comparison of two treatment types | Community | Naturalistic Outcomes of Evidence-Based Therapies for Borderline Personality Disorder at a Medical University Clinic |

| 15 | Hjalmarsson et al. (2008) | DBT | Sweden | Feasibility study | Community | Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder Among Adolescents and Young Adults: Pilot Study, Extending the Research Findings in new Settings and Cultures |

| 16 | Jørgensen et al. (2013) | MBT and SGT | Denmark | Randomised partly controlled outcome study | Community | Outcome of Mentalization-Based and Supportive Psychotherapy in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Trial |

| 17 | Koons et al. (2001) | DBT and TAU | America | Randomised controlled trial | Community | Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Women Veterans with Borderline Personality Disorder |

| 18 | Kröger et al. (2013) | DBT | Germany | Effectiveness study | Inpatient | Effectiveness, Response, and Dropout of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder in an Inpatient Setting |

| 19 | Lopez et al. (2015) | UP | America | Multiple baseline single-case efficacy study | Community | Examining the Efficacy of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders in the Treatment of Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder |

| 20 | Lyng et al. (2020) | DBT | UK | Effectiveness study | Community | Outcomes for 18 to 25 year-olds with Borderline Personality Disorder in a Dedicated Young Adult Only DBT Programme Compared to a General Adult DBT Programme for all Ages 18 |

| 21 | Meares et al. (1999) | Psychodynamic therapy | Australia | Efficacy study | Community | Psychotherapy with Borderline Patients: I. A Comparison Between Treated and Untreated Cohorts |

| 22 | Morey et al. (2010) | MACT | America | Pilot study | Community | A Pilot Study of Manual-Assisted Cognitive Therapy with a Therapeutic Assessment Augmentation for Borderline Personality Disorder |

| 23 | Nadort et al. (2009) | SFT with and without crisis phone support | The Netherlands | Randomised controlled trial | Community | Implementation of Outpatient Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder with Versus without Crisis Support by the Therapist Outside Office Hours: A Randomized Trial |

| 24 | Nysæter et al. (2010) | Long-term non-manualised psychotherapy | Norway | Naturalistic follow up study | Community | A Preliminary Study of The Naturalistic Course of Non-Manualized Psychotherapy for Outpatients with Borderline Personality Disorder: Patient Characteristics, Attrition and Outcome |

| 25 | Rizvi et al. (2017) | DBT | America | Effectiveness study | Community | Can Trainees Effectively Deliver Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder? Outcomes from a Training Clinic |

| 26 | Ryle and Golynkina (2000) | CAT | UK | Naturalistic uncontrolled effectiveness study | Community | Effectiveness of Time-Limited Cognitive Analytic Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder: Factors Associated with Outcome |

| 27 | Salzer et al. (2014) | Psychodynamic therapy | Germany | Efficacy study | Inpatient | Early Intervention for Borderline Personality Disorder: Psychodynamic Therapy in Adolescents |

| 28 | Stevenson and Meares (1992) | Psychodynamic therapy | Australia | Effectiveness study | Community | An Outcome Study of Psychotherapy for Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder |

CAT: cognitive analytic therapy; CT: cognitive therapy; DBT: dialectical behaviour therapy; DBT-ER: emotion regulation module from DBT; DBT-IE: interpersonal effectiveness module from DBT; DBT-M: mindfulness module from DBT; DDP: dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy; ERGI: Emotion Regulation Group Intervention; Fluoxetine: antidepressant; IPT-BPD: interpersonal therapy for borderline personality disorder; MACT: manual assisted cognitive therapy; MBT: mentalisation-based therapy; SCM: structured clinical management; SGT: supportive group therapy; SFT: schema-focused therapy; SFT-G: Schema Focused Therapy Group; STEPPS: systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving; TAU: treatment as usual; TFP: transference-focused psychotherapy; UP: the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders.

Participant characteristics

The characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 2. The total number of participants in the included studies was 2436 (range N = 1423 to N = 6). The study with 1423 participants, which investigated the effectiveness of 3-month inpatient DBT programme (Kröger et al., 2013), had a markedly different sample size compared to the other studies. The mean sample size including the Kröger et al. (2013) study was 56.65 (213.87) with a range of 6–1423. The mean excluding the Kröger et al. (2013) study was 24.12 (15.43) with a range of 6–71. The mean age of the participants was 30.39 years of age (SD = 4.57) with a range of 16.9–40. Only two studies reported the demographics for the entire sample (Dickhaut and Arntz, 2014; Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015). Where this occurred, the entire sample values were reported for each group. One study did not report the mean age of their participants; however, they did report that their inclusion criteria were to be between the ages of 18 and 45 (Doering et al., 2010). One study did not report on gender (Meares et al., 1999), and the remaining studies had predominantly female samples (15 studies 100% female). The mean proportion of females across samples was 88.67% (SD = 11.88) with a range of 59.30–100%. Of the 28 included studies, 17 reported data regarding psychotropic medication use. The majority of these reported the percentage of the sample taking any type of psychotropic medication, while some reported medications by type. Common medications included antidepressants, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics and mood stabilisers.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

| Study number | Treatment type (comparison treatment) | Sample size (N analysed) | Age M (SD) |

Female (%) | Psychotropic medication (%) | Caucasian (%) | Employed (%) | Single (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MBT | 71 | 31.3 (7.6) | 80.3 | 77.50 | 76.10 | 28.20 | 42.30 |

| (SCM) | 63 | 30.9 (7.9) | 79.4 | 68.3 | 68.30 | 30.20 | 49.20 | |

| 2 | IPT-BPD + fluoxetine | 22 | 26.23 (6.4) | 70.37 | 100 | NR | 48.15 | 55.56 |

| 3 | DBT | 8 | 29.4 | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 4 | STEPPS | 52 | 33 (9) | 94.2 | 100.00 | NR | NR | NR |

| 5 | CT | 29 | 29 | 88 | 52.00 | 72.00 | 53.00 | 87.00 |

| 6 | SFT – facilitators untrained in group SFT | 8 | 28.5 (8.7) | 100 | 72.20 | NR | 22.20 | NR |

| (SFT – facilitators trained by specialists in group SFT) | 10 | 28.5 (8.7) | 100 | 72.20 | NR | 22.20 | NR | |

| 7 | DBT-ER | 7 | 34.47 (11.83) | 100 | 73.70 | 63.20 | NR | 73.70 |

| (DBT-IE) | 6 | 34.47 (11.83) | 100 | 73.70 | 63.20 | NR | 73.70 | |

| (Psychoeducation control group) | 6 | 34.47 (11.83) | 100 | 73.70 | 63.20 | NR | 73.70 | |

| 8 | TFP | 43 | NR | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| (TAU) | 29 | NR | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| 9 | DBT-M | 32 | 31.56 (7.25) | 84.4 | 48.33 | NR | NR | 62.50 |

| (DBT-IE) | 32 | 31.72 (6.82) | 87.5 | 30.20 | NR | NR | 50.00 | |

| 10 | SFT-G + TAU | 16 | 35.3 (9.3) | 100 | 100.00 | NR | 69.00 | NR |

| (TAU) | 12 | 35.9 (8.1) | 100 | 100.00 | NR | 50.00 | NR | |

| 11 | SFT | 44 | 31.7 (8.9) | 90.9 | 73.30 | NR | 20.50 | NR |

| (TFP) | 42 | 29.5 (6.5) | 95.2 | 71.40 | NR | 19.00 | NR | |

| 12 | ERGI + TAU | 12 | 33 (12.47) | 100 | NR | 100.00 | NR | 58.30 |

| 13 | DDP | 15 | 28.3 (7.1) | 87 | NR | 86.00 | 33.00 | 87.00 |

| (TAU) | 15 | 29 (8.6) | 73 | NR | 93.00 | 33.00 | 93.00 | |

| 14 | DDP | 27 | 28 (11.7) | 85 | NR | 89.00 | 41.00 | 78.00 |

| (DBT) | 25 | 36.6 (10.2) | 84 | NR | 84.00 | 36.00 | 52.00 | |

| (TAU) | 16 | 29.3 (11.5) | 69 | NR | 94.00 | 25.00 | 75.00 | |

| 15 | DBT | 15 | 20.2 (5.6) | 100 | 71.00 | NR | NR | 89.00 |

| 16 | MBT | 39 | 29.2 (6.1) | 96 | 70.00 | NR | 10.00 | 50.00 |

| (SGT) | 19 | 29 (6.4) | 95 | 68.00 | NR | 5.00 | 38.00 | |

| 17 | DBT | 10 | 35 | 100 | NR | 75.00 | NR | 45.00 |

| (TAU) | 10 | 35 | 100 | NR | 75.00 | NR | 45.00 | |

| 18 | DBT | 1423 | 32 (10.3) | 75.5 | NR | NR | 39.80 | 79.80 |

| 19 | UP | 8 | 40 | 100 | NR | 87.50 | NR | 62.50 |

| 20 | DBT – young people only | 19 | 20.5 (1.91) | 83.3 | 70.80 | NR | 66.70 | NR |

| (DBT – grouped with older adults) | 11 | 21.46 (2.15) | 69.2 | 84.60 | NR | 46.20 | NR | |

| 21 | Psychodynamic therapy | 30 | 29.4 (7.9) | NR | NR | NR | 26.66 | 83.33 |

| 22 | MACT | 7 | 31.1 (8.9) | 81.25 | 56.00 | 87.50 | 25.00 | 62.50 |

| 23 | SFT + crisis phone support | 30 | 31.8 (9.24) | 96.9 | 59.40 | NR | 25.00 | NR |

| (SFT without crisis phone support) | 31 | 32.13 (9.01) | 96.7 | 56.70 | NR | 26.70 | NR | |

| 24 | Long-term non-manualised psychotherapy | 23 | 28.9 (6.1) | 81 | 22.00 | NR | 44.00 | 47.00 |

| 25 | DBT | 34 | 29.52 (9.64) | 80 | NR | 68.00 | 54.00 | 72.00 |

| 26 | CAT | 27 | 34.3 (7.5) | 59.3 | 51.85 | NR | 55.56 | 33.33 |

| 27 | Psychodynamic therapy | 28 | 16.9 (1.1) | 78.6 | 64.30 | NR | NR | NR |

| 28 | Psychodynamic therapy | 30 | 29.4 (7.9) | 63.3 | NR | NR | 26.70 | NR |

| Mean (SD) | 56.65 (213.87) SUM = 2436 |

30.39 (4.57) | 88.67 (11.88) | 69.08 (19.10) | 79.12 (11.87) | 35.06 (15.91) | 63.65 (17.29) |

%: percentage of sample; CAT: cognitive analytic therapy; CT: cognitive therapy; DBT: dialectical behaviour therapy; DBT-ER: emotion regulation module from DBT; DBT-IE: interpersonal effectiveness module from DBT; DBT-M: mindfulness module from DBT; DDP: dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy; ERGI: Emotion Regulation Group Intervention; Fluoxetine: antidepressant; IPT-BPD: interpersonal therapy for borderline personality disorder; MACT: manual assisted cognitive therapy; MBT: mentalisation-based therapy; SCM: structured clinical management; SGT: supportive group therapy; SFT: schema-focused therapy; SFT-G: Schema Focused Therapy Group; STEPPS: systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving; TAU: treatment as usual; TFP: transference-focused psychotherapy; UP: the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders.

Notes regarding data reporting: In the Morey et al. (2010) study, there were two groups; however, the authors reported the demographic data grouped by the entire sample. Therefore, this review will also report their results as one group. The Bellino et al. (2010) study comprised two treatment groups. One was ITP-BPD + fluoxetine (psychological therapy plus antidepressant pharmacotherapy) and the other was fluoxetine (antidepressant pharmacotherapy) only. The data from the group treated with both the psychotherapy and the antidepressant is reported, while the data from the fluoxetine only group was omitted, since this review is concerned only with the effectiveness of psychotherapies. The Gratz and Gunderson (2006) study comprised two groups. One was treated with an Emotion Regulation Group Intervention (ERGI) plus Treatment as Usual (TAU), the other was treated with TAU only. However, the main outcome (percent of sample not responded) was only reported for the treatment group (ERGI + TAU). Therefore, the data from the TAU only group was omitted. The Meares et al. (1999) reported on a control group; however, the data from this group was omitted because they were a waitlist group that did not receive any treatment.

Occasionally, studies reported demographic information for the entire participant group, instead of separately by treatment groups. Where this occurred, the overall sample values were reported for each group. Some studies used intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses. Where this occurred, the ITT sample size was reported as opposed to the sample size of completers only.

Comorbidities and clinical characteristics

Twenty studies identified comorbid diagnoses of their participants, although the method of reporting comorbidities varied significantly between studies. This created challenges regarding presentation of the data; the available information has been tabularised and is available as Supplementary Material.

Eight studies reported comorbidities by the mean of Axis I disorders. The overall mean of Axis I disorders was M = 2.69 (SD = 0.62) with a range of 1.40–3.70. Six studies reported comorbidities by the mean number of additional Axis II disorders. The overall mean of Axis II disorders was M = 2.14 (SD = 1.25) with a range of 0.88–4.90. Seventeen studies reported the number of disorders identified in addition to BPD. The number of disorders listed cannot be considered accurate because not all studies conducted standardised structured diagnostic interviews for all possible diagnoses. Instead, they screened for disorders that were in their exclusion criteria or they identified a select set of typically co-occurring disorders. Alternatively, they identified a large number of other disorders but only reported specific data on the most frequently occurring ones. Therefore, although the Supplementary Material presents findings that the number of comorbid disorders ranged from 1 to 13 with a mean of 4.59 (SD = 2.71), these values must be considered a conservative estimate.

The most commonly reported and frequently co-occurring disorders were any mood disorder, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, self-harming behaviours and personality disorders. Twelve studies identified any mood disorder as a comorbid diagnosis. The percentage of their samples that had a concurrent mood disorder ranged from 25.00% to 95.80% with a mean of 69.93% (SD = 15.05). Eleven studies identified and reported on anxiety disorders. The percentages of their samples that had concurrent anxiety disorders ranged from 19% to 90.60% with a mean of 49.39% (SD = 20.06). Eleven studies identified and reported on eating disorders. The percentages of the samples that had concurrent eating disorders ranged from 6.00% to 56.00% with a mean of 35.00% (SD = 12.52). Fifteen studies identified current or historical substance abuse. Some studies differentiated between alcohol and other substances. Where this distinction was made, the higher percentage was reported. The percentages of their samples with current or historical substance abuse ranged from 12.50% to 77.40% with a mean of 40.20% (SD = 20.17). Seventeen studies identified current or historical self-harming behaviours. The percentages of their samples with current or historical self-harming behaviours ranged from 18.58% to 100.00% with a mean of 73.03% (SD = 23.10). Self-harm was not counted as a comorbid disorder. Seven studies identified current concurrent personality disorders. Some studies identified ‘other personality disorders’, some as clusters and some as specific disorders. Where they were differentiated the mean was taken and reported. The percentages of their samples with concurrent personality disorders ranged from 32.40% to 100.00% with a mean of 56.26% (SD = 22.15).

Although collectively there is evidence of considerable comorbidities in this population, many studies excluded participants on this basis. Twenty studies excluded psychotic type disorders, 9 excluded bipolar disorder, 17 excluded participants who had an active or severe substance use disorder that required specialist care and 5 excluded any type of substance use disorder. One study excluded participants if they had any comorbidities (Bellino et al., 2010).

Treatment characteristics and results

In total, there were 43 distinct participant groups among the 28 included studies. The groups were treated with varying types of psychotherapy. In order of most frequently occurring, 12 groups were treated with DBT or a stand-alone module of DBT, 6 with SFT or a variant of SFT, 5 with TAU, 3 with generalised psychodynamic therapy, 2 with MBT, 2 with TFP, 2 with dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy (DDP), 1 with manual assisted cognitive therapy (MACT), 1 with long-term non-manualised psychotherapy, 1 with cognitive analytic therapy (CAT), 1 with systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (STEPPS), 1 with interpersonal therapy for borderline personality disorder (IPT-BPD) + fluoxetine, 1 with CT, 1 with Emotion Regulation Group Intervention (ERGI) + TAU, 1 with the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders (UP), 1 with structured clinical management (SCM) as a comparison, 1 with supportive group therapy (SGT) as a comparison and 1 with psychoeducational control group as a comparison. Of these 18 different psychotherapies, 10 are specifically designed for the treatment of BPD, the remaining are generalised psychotherapies that can be used or modified for the treatment of BPD. In the present study, TAU and the other comparison groups (SCM, SGT, psychoeducation) were given equal weight as psychotherapies. The results from these groups are considered equally important to report because it can be more common for people with BPD to receive TAU-type psychotherapies than manualised psychotherapies specifically for BPD (Hutsebaut et al., 2020; Iliakis et al., 2019). Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis found that BPD symptoms consistently reduce with TAU treatments and that the benefits of TAU increase as more time is spent in treatment (Finch et al., 2019). Moreover, this review sought a real-world estimate of the percentage of people who are not responding to the psychotherapies available to those living with BPD. Including TAU treatments ensures this review is capturing a sample that is more representative of the population. These results are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Treatment characteristics and results.

| Study number | Treatment type (comparison treatment) | Sample size (N analysed) | Dropout between treatment commencement and cessation (%) | Treatment duration (months) | Sample not responded (%) | Determination of response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MBT | 71 | 27.66 | 18.0 | 22.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| (SCM) | 63 | 25.40 | 18.0 | 56.0 | ||

| 2 | IPT-BPD + fluoxetine | 22 | 18.52 | 8.0 | 45.5 | A 50% reduction on the BPD-SI total score and a score of 1 very much improved or 2 much improved on the CGI |

| 3 | DBT | 8 | 20.00 | 6.0 | 100.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| 4 | STEPPS | 52 | 0.00 | 5.0 | 58.6 | A 25% or greater reduction on the BEST score |

| 5 | CT | 29 | 9.38 | 12.0 | 48.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| 6 | SFT – facilitators untrained in group SFT | 8 | 37.50 | 24 | 81.3 | Achieving a BPDSI-IV score of less than 15 and maintaining this score until the last assessment |

| (SFT – facilitators trained by specialists in group SFT) | 10 | 40.00 | 24 | 33.5 | ||

| 7 | DBT-ER | 7 | 16.66 | 2 | 43.0 | Reaching RCI on the PAI-BOR |

| (DBT-IE) | 6 | 16.66 | 2 | 40.0 | ||

| (Psycho-ed control group) | 6 | 0.00 | 2 | 60.0 | ||

| 8 | TFP | 43 | 38.50 | 12 | 48.8 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| (TAU) | 29 | 67.30 | 12 | 72.6 | ||

| 9 | DBT-M | 32 | 41.00 | 2.5 | 60.0 | Reaching RCI on the BSL-23 |

| (DBT-IE) | 32 | 19.00 | 2.5 | 87.0 | ||

| 10 | SFT-G + TAU | 16 | 0.00 | 8 | 6.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD using the DIB-R |

| (TAU) | 12 | 25.00 | 8 | 75.0 | ||

| 11 | SFT | 44 | 26.67 | 36 | 43.1 | Reaching RCI on the BPDSI-IV |

| (TFP) | 42 | 51.16 | 36 | 57.1 | ||

| 12 | ERGI + TAU | 12 | 8 | 3.5 | 50.0 | Reaching RCI on the BEST. |

| 13 | DDP | 15 | 33.00 | 12 | 10.0 | A 25% reduction in BEST scores |

| (TAU) | 15 | 40.00 | 12 | 62.0 | ||

| 14 | DDP | 27 | 33.33 | 12 | 11.0 | A 25% reduction in BEST scores |

| (DBT) | 25 | 64.00 | 12 | 33.0 | ||

| (TAU) | 16 | 69.00 | 12 | 60.00 | ||

| 15 | DBT | 15 | 18.52 | 12 | 73.0 | Reaching RCI on the borderline subscale of the KABOSS-S |

| 16 | MBT | 39 | 32.76 | 18 | 48.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| (SGT) | 19 | 29.63 | 18 | 59.0 | ||

| 17 | DBT | 10 | 23.08 | 6 | 30.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| (TAU) | 10 | 16.66 | 6 | 50.0 | ||

| 18 | DBT | 1423 | 10.00 | 3 | 55.0 | Reaching RCI on the BSL |

| 19 | UP | 8 | 11.11 | 6 | 37.5 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| 20 | DBT – young people only | 19 | 20.80 | 12 | 31.6 | Reaching RCI on the BSL-23 |

| (DBT – grouped with older adults) | 11 | 15.40 | 12 | 9.1 | ||

| 21 | Psychodynamic therapy | 30 | 22.92 | 12 | 70.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| 22 | MACT | 7 | 56.00 | 1.5 | 29.0 | Reaching RCI on the PAI-BOR |

| 23 | SFT + crisis phone support | 30 | 21.88 | 18 | 48.4 | Reaching RCI on the BPDSI-IV |

| (SFT without crisis phone support) | 31 | 20.00 | 18 | 36.7 | ||

| 24 | Long-term non-manualised psychotherapy | 23 | 28.00 | 18 | 38.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| 25 | DBT | 34 | 32.00 | 6 | 41.0 | Reaching RCI and CSC on the BSL-23 |

| 26 | CAT | 27 | 12.90 | 7 | 48.0 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD using the Personality Assessment Schedule |

| 27 | Psychodynamic therapy | 28 | 25.00 | 7.5 | 67.7 | No longer meeting criteria for BPD |

| 28 | Psychodynamic therapy | 30 | 16.67 | 12 | 70.0 | No longer criteria for BPD |

| Means | 56.65 (213.87) SUM = 2436 |

26.54 (16.67) | 11.50 (8.09) | 48.80 (22.77) | RCI: 19 (53.57%) Criteria: 13 (46.43%) |

%: percentage; BEST: borderline evaluation of severity over time; BPDSI-IV: DSM-IV based structured interview for Borderline Personality Disorder; BPD-SI: Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index; BSL and BSL-23: borderline symptoms list; CAT: cognitive analytic therapy; CGI: clinical global impression; CT: cognitive therapy; DBT: dialectical behaviour therapy; DBT-ER: emotion regulation module from DBT; DBT-IE: interpersonal effectiveness module from DBT; DBT-M: mindfulness module from DBT; DDP: dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy; ERGI: Emotion Regulation Group Intervention; Fluoxetine: antidepressant; IPT-BPD: interpersonal therapy for borderline personality disorder; MACT: manual assisted cognitive therapy; MBT: mentalisation-based therapy; SCM: structured clinical management; SGT: supportive group therapy; SFT: schema-focused therapy; SFT-G: Schema Focused Therapy Group; STEPPS: systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving; TAU: treatment as usual; TFP: transference-focused psychotherapy; UP: the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders.

Drop out

Some studies reported the percentage of drop out from their participant samples. Others reported sample size at various stages of the study (i.e. N recruited, N excluded before commencement, N dropped out between treatment commencement and cessation). Where the percentage had to be calculated by the review team, it was calculated based on the number of participants who dropped out during the treatment stage. Across studies, drop out ranged from 0.0% to 69.00% with a mean of 26.54% (SD = 16.67).

Treatment duration

Some studies reported the treatment duration as a range of months. Where this occurred the middle of the range (Nysæter et al., 2010), or the average length of treatment was reported. Treatment periods ranged from 1.5 to 36 months with a mean of 11.50 months (SD = 8.09).

Determination of response

Thirteen studies (46.43%) operationalised response as no longer meeting criteria for BPD at the end of treatment. Nineteen studies (53.57%) operationalised response as meeting RCI criteria, or a pre-determined reduction in scores, on a BPD-specific measure.

Main outcome results

The proportion of participants who did not respond to treatment ranged from 6% to 100% with a mean of 48.80% (SD = 22.77). Across studies there was a high variance in sample size and treatment duration. Therefore, the mean was also calculated weighted by sample size; M = 52.38% (SD = 12.47) and treatment duration; M = 48.09% (SD = 19.60). Determination of non-response method was compared: meeting criteria (N = 18), M = 52.20% (SD = 21.71), was slightly higher compared to not meeting RCI criteria (N = 25); M = 46.36% (SD = 20.16). However, this difference was not significant; t(41) = 0.908, p = 0.369, 95% CI = [−7.15, 18.84]. The mean percentage of non-response among the groups treated with psychotherapies specifically designed for BPD (N = 31) was slightly lower M = 46.05% (SD = 22.89) compared with the percentage of non-response among the groups treated with generalised psychotherapies (N = 12), M = 55.90% (SD = 11.93). However, this difference was not significant; t(41) = −1.410, p = 0.166, 95% CI = [−23.94, 4.25]. The limited amount of data precludes the ability to conduct sub-group analyses; however, the mean non-response among the samples treated with DBT was M = 47.15% (SD = 29.20), SFT was M = 41.5% (SD = 24.42), TAU was M = 63.92% (SD = 10.14), and the psychodynamic groups combined (generalised, MBT, DDP, TFP) was M = 41.95% (SD = 24.34).

Discussion

This review sought to obtain an informed estimate of the proportion of people who are not responding to psychotherapy for BPD. Twenty-eight studies, comprising 2436 participants, met inclusion criteria and were reviewed. Across studies non-response ranged from 6% to 100% with a mean of 48.80% (SD = 22.77). The mean was also calculated as weighted by sample size and treatment duration due to large variations in these factors; however, the weighted means were not markedly different from the non-weighted mean.

Analyses of secondary data demonstrated no differences in rates of non-response between the two methods of non-response determination (still meeting BPD criteria vs not reaching RCI), or treatment types (specialised vs non-specialised psychotherapies) for BPD. This finding is consistent with previous research that has reported that specialised therapies had no greater effect on remission rates than did treatment as usual (70% vs 52%, p = 0.45) and that clinical trials did not effectuate greater rates of remission compared to naturalistic studies (61% vs 59%, p = 0.85) (Álvarez-Tomás et al., 2019). These results, and the findings from the current review, are consistent with the body of literature which demonstrates that generalist models produce similar results to specialist treatments (Choi-Kain et al., 2017; Gunderson et al., 2018).

This review highlights non-response to psychotherapy for BPD as a pressing problem. Approximately half of treatment consumers are not responding to treatment. Although non-response is already a well-known phenomenon in psychiatry (Lambert, 2011; Wampold and Imel, 2015), there is a notable lack of focused research into non-response in the field of psychotherapy for BPD. Understanding non-response more thoroughly, and the factors that contribute to the problem, may assist clinicians to recognise sooner which clients may need extra or different support to respond to treatment. Presently, there are no clear guidelines on how to make predictions about prognosis; therefore, it remains a challenging for clinicians to plan treatment to prevent non-response (Lambert, 2011, 2013; Spinhoven et al., 2008).

A strength of this review is that it encompasses study designs beyond RCTs. Many of the studies were naturalistic, pilot or efficacy studies taking place in real-world community settings with therapists of differing levels of experience. This allows for greater generalisability and ensures a more accurate estimate under real-world conditions.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations in this review. First, there was a high level of missingness in the secondary data (i.e. comorbidities and dosages) due to inconsistencies of reporting methods. Therefore, not all factors had sufficient data to be reported or analysed. As such, predictive analyses could not be undertaken that explored their influence on non-response. Many studies excluded people with psychotic disorders, severe substance misuse and bipolar from their samples. Although rationales were provided for this practice, it means we remain uninformed about the rates of non-response among people with these commonly co-occurring disorders. A general limitation has been discussed already: that many well-known studies in the field are silent on reporting non-response and thus could not be included in this review. Many studies had samples who were all or predominately female. This creates barriers for the generalisability considering that it is evident that BPD is not a predominantly female disorder (Tomko et al., 2014). A further limitation is the exclusion of papers published in languages other than English. It is acknowledged that important papers that may have included the data sought in this review; however, it was beyond the scope of this review to search beyond the English language. Finally, the number of included studies precluded the ability to conduct any sensitivity analyses which limited the extent to which comparative explorations could be made and may limit the weight that can be given to the results.

It is also acknowledged that non-response as defined in the current review is only one way of assessing the success of treatment outcomes. Improving after psychotherapy is a complex phenomenon that may continue long after treatment ceases and comprises not only of a reduction in symptoms but of increases in occupational functioning, social connectedness and living a fulfilling life. However, these aspects of recovery are more difficult to operationalise and capture from the data available in outcome studies, despite being important benefits from treatment.

Recommendations

The majority of psychotherapy outcome studies routinely collect data on a range of factors such as demographics, comorbidities, psychotropic medication use and treatment factors. However, the data are collected using such divergent methods that create difficulties when attempting to conduct analyses to explore these factors as contributors to non-response. Having more consistent and standardised methods for collecting and reporting data in outcomes studies would be helpful for future research. For instance, when reporting on treatment dosage, displaying range, modes, means and totals of the number of sessions and hours of treatment delivered across each week and the whole treatment period would allow for investigation of dosage as a possible contributor to non-response. Including reporting non-response as defined here should be standard in all outcome studies.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that approximately half the people who receive psychotherapy for BPD do not respond to treatment regardless of treatment type or treatment length. Factors contributing to the problem of non-response remain unclear. Direct quantitative and qualitative research, in addition to more consistent reporting of a wider range of possible contributing factors, may be helpful. It is further recommended that future researchers consult clinicians and consumers to seek their perspectives on why some people are not responding to psychotherapy for BPD.

Research Data

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-anp-10.1177_00048674211046893 for Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review by Jane Woodbridge, Michelle Townsend, Samantha Reis, Saniya Singh and Brin FS Grenyer in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Supplemental material, sj-sav-2-anp-10.1177_00048674211046893 for Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review by Jane Woodbridge, Michelle Townsend, Samantha Reis, Saniya Singh and Brin FS Grenyer in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-anp-10.1177_00048674211046893 for Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review by Jane Woodbridge, Michelle Townsend, Samantha Reis, Saniya Singh and Brin FS Grenyer in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-anp-10.1177_00048674211046893 for Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review by Jane Woodbridge, Michelle Townsend, Samantha Reis, Saniya Singh and Brin FS Grenyer in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The primary source of funding for this review was the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship (J.W.); Project Air Strategy acknowledges the support of the NSW Ministry of Health.

Registration: The protocol was registered by the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42020147289).

ORCID iD: Brin FS Grenyer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1501-4336

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1501-4336

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Álvarez-Tomás I, Ruiz J, Guilera G, et al. (2019) Long-term clinical and functional course of borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. European Psychiatry 56: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (ed.) (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsen BT, Kvarstein EH, Urnes Hummelen ØB, et al. (2017) Favourable outcome of long-term combined psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder: Six-year follow-up of a randomized study. Psychotherapy Research 27: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntz A, Stupar-Rutenfrans S, Bloo J, et al. (2015) Prediction of treatment discontinuation and recovery from borderline personality disorder: Results from an RCT comparing schema therapy and transference focused psychotherapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy 74: 60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RC, Grenyer BFS. (2014) Supporting a person with personality disorder: A study of carer burden and well-being. Journal of Personality Disorders 28: 796–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnicot K, Crawford M. (2019) Dialectical behaviour therapy v. mentalisation-based therapy for borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine 49: 2060–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. (1999) Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry 156: 1563–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. (2008) 8-year follow-up of patients treated for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization-based treatment versus treatment as usual. The American Journal of Psychiatry 165: 631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. (2013) Impact of clinical severity on outcomes of mentalisation-based treatment for borderline personality disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 203: 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellino S, Rinaldi C, Bogetto F. (2010) Adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy to borderline personality disorder: A comparison of combined therapy and single pharmacotherapy. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 55: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Blum N, McCormick B, et al. (2013) Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) Group treatment for offenders with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 201: 124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennerhassett R, Bamford L, Whelan A, et al. (2009) Dialectical behaviour therapy in an Irish community mental health setting. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 26: 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum N, Pfohl B, St John D, et al. (2002) STEPPS: A cognitive-behavioral systems-based group treatment for outpatients with borderline personality disorder – A preliminary report. Comprehensive Psychiatry 43: 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohus M. (2008) Effectiveness of dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder under inpatient conditions: A controlled trial and follow-up data. European Psychiatry 23: S65. [Google Scholar]

- Bos EH, van Wel EB, Appelo MT, et al. (2011) Effectiveness of Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for borderline personality problems in a ‘real-world’ sample: Moderation by diagnosis or severity. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 80: 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs J. (2020) critical-appraisal-tools: Critical appraisal tools | Joanna Briggs Institute [WWW Document]. Available at: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed 28 August 2021).

- Broadbear JH, Dwyer J, Bugeja L, et al. (2020) Coroners’ investigations of suicide in Australia: The hidden toll of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 129: 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Newman CF, Charlesworth SE, et al. (2004) An open clinical trial of cognitive therapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 18: 257–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McCutcheon LK, et al. (2009) Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: Quasi-experimental comparison with treatment as usual. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 43: 397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi-Kain LW, Finch EF, Masland SR, et al. (2017) What works in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports 4: 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, et al. (2007) Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: A multiwave study. The American Journal of Psychiatry 164: 922–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA, Russo J, Snowden M, et al. (2003) Factors associated with high use of public mental health services by persons with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Services 54: 1149–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD, et al. (2017) Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 74: 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K, Norrie J, Tyrer P, et al. (2006) The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: Results from the Borderline Personality Disorder Study of Cognitive Therapy (BOSCOT) Trial. Journal of Personality Disorders 20: 450–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickhaut V, Arntz A. (2014) Combined group and individual schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 45: 242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, Turner BJ. (2015) A preliminary pilot study comparing dialectical behavior therapy emotion regulation skills with interpersonal effectiveness skills and a control group treatment. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology 6: 369–388. [Google Scholar]

- Doering S, Hörz S, Rentrop M, et al. (2010) Transference-focused psychotherapy v. treatment by community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 196: 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elices M, Pascual JC, Portella MJ, et al. (2016) Impact of mindfulness training on borderline personality disorder: A randomized trial. Mindfulness 7: 584–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell JM, Shaw IA, Webber MA. (2009) A schema-focused approach to group psychotherapy for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 40: 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertuck EA, Keilp J, Song I, et al. (2012) Higher executive control and visual memory performance predict treatment completion in borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 81: 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch EF, Iliakis EA, Masland SR, et al. (2019) A meta-analysis of treatment as usual for borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment 10: 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, et al. (2006) Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 63: 649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. (2008) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 69: 533–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Gunderson JG. (2006) Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy 37: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Bardeen JR, Levy R, et al. (2015) Mechanisms of change in an emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 65: 29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RJ, Sachdeva S. (2016) Naturalistic outcomes of evidence-based therapies for borderline personality disorder at a medical university clinic. American Journal of Psychotherapy 70: 167–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RJ, Chlebowski S, Kang D, et al. (2006) Psychodynamic therapy for borderline personality disorder and co-occurring alcohol use disorders: A newly designed ongoing study. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 54: 1331–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RJ, Deranja E, Mogle JA. (2010) Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder comorbid with alcohol use disorders: 30-month follow-up. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 58: 560–566. [Google Scholar]

- Grenyer BFS. (2013) Improved prognosis for borderline personality disorder. Medical Journal of Australia 198: 464–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenyer BFS, Bailey R, Lewis KL, et al. (2019) A randomised controlled trial of group psychoeducation for carers of persons with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 33: 214–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenyer BFS, Jenner B, Jarman H, et al. (2015) Treatment Guidelines for Personality Disorders (Project Air Strategy for Personality Disorders), 2nd Edition. Wollongong, NSW, Australia: Illawarra Health and Medical Research Institute, University of Wollongong. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson J, Masland S, Choi-Kain L. (2018) Good psychiatric management: A review. Current Opinion in Psychology 21: 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG. (2009) Borderline personality disorder: Ontogeny of a diagnosis. The American Journal of Psychiatry 166: 530–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Singer MT. (1975) Defining borderline patients: An overview. The American Journal of Psychiatry 132: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Daversa MT, Grilo CM, et al. (2006) Predictors of 2-year outcome for patients with borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry 163: 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjalmarsson E, Kåver A, Perseius K-I, et al. (2008) Dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder among adolescents and young adults: Pilot study, extending the research findings in new settings and cultures. Journal of Clinical Psychology 12: 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hörz S, Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, et al. (2010) Ten-year use of mental health services by patients with borderline personality disorder and with other axis II disorders. Psychiatric Services 61: 612–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsebaut J, Willemsen E, Bachrach N, et al. (2020) Improving access to and effectiveness of mental health care for personality disorders: The guideline-informed treatment for personality disorders (GIT-PD) initiative in the Netherlands. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation 7: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliakis EA, Sonley AKI, Ilagan GS, et al. (2019) Treatment of borderline personality disorder: Is supply adequate to meet public health needs? Psychiatric Services 70: 772–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen CR, Freund C, Bøye R, et al. (2013) Outcome of mentalization-based and supportive psychotherapy in patients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized trial – Outcome of psychotherapy in BPD patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 127: 305–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. (1991) Clinical significance: A statistical approach to Denning meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59: 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, Schmahl C, et al. (2008) Do improvements after inpatient dialectial behavioral therapy persist in the long term?: A naturalistic follow-up in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196: 847–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koons CR, Robins CJ, Lindsey Tweed J, et al. (2001) Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Therapy 32: 371–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kröger C, Harbeck S, Armbrust M, et al. (2013) Effectiveness, response, and dropout of dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder in an inpatient setting. Behaviour Research and Therapy 51: 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ. (2011) What have we learned about treatment failure in empirically supported treatments? Some suggestions for practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 18: 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ. (2013) Outcome in psychotherapy: The past and important advances. Psychotherapy 50: 42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, et al. (2011) Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet 377: 74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy KN, McMain S, Bateman A, et al. (2018) Treatment of borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 41: 711–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 62: e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. (2006) Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 63: 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez ME, Stoddard JA, Noorollah A, et al. (2015) Examining the efficacy of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in the treatment of individuals with borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 22: 522–533. [Google Scholar]

- Lyng J, Swales MA, Hastings RP, et al. (2020) Outcomes for 18 to 25-year-olds with borderline personality disorder in a dedicated young adult only DBT programme compared to a general adult DBT programme for all ages 18+. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 14: 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH. (1986) The Chestnut Lodge follow-up study: III long-term outcome of borderline personalities. Archives of General Psychiatry 43: 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, et al. (2009) A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry 166: 1365–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meares R, Stevenson J, Comerford A. (1999) Psychotherapy with borderline patients: I – A comparison between treated and untreated cohorts. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 33: 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuldijk D, McCarthy A, Bourke ME, et al. (2017) The value of psychological treatment for borderline personality disorder: Systematic review and cost offset analysis of economic evaluations. PLoS ONE 12: e0171592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran LR, Kaplan C, Aguirre B, et al. (2018) Treatment effects following residential dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health 3: 117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Lowmaster SE, Hopwood CJ. (2010) A pilot study of manual-assisted cognitive therapy with a therapeutic assessment augmentation for borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research 178: 531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton J, Snowdon S, Gopold M, et al. (2012) Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Group treatment for symptoms of borderline personality disorder: A public sector pilot study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 19: 527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Nadort M, Arntz A, Smit JH, et al. (2009) Implementation of outpatient schema therapy for borderline personality disorder with versus without crisis support by the therapist outside office hours: A randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy 47: 961–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2012) Clinical practice guideline: Borderline personality disorder (WWW document). NHMRC. Available at: www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/clinical-practice-guideline-borderline-personality-disorder (accessed 28 August 2021).

- Ng FYY, Bourke ME, Grenyer BFS. (2016) Recovery from borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of the perspectives of consumers, clinicians, family and carers. PLoS ONE 11: e0160515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nysæter TE, Nordahl HM, Havik OE. (2010) A preliminary study of the naturalistic course of non-manualized psychotherapy for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: Patient characteristics, attrition and outcome. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 64: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucker HE, Temes CM, Zanarini MC. (2019) Description and prediction of social isolation in borderline patients over 20 years of prospective follow-up. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment 10: 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Hughes CD, Hittman AD, et al. (2017) Can trainees effectively deliver dialectical behavior therapy for individuals with borderline personality disorder? Outcomes from a training clinic. Journal of Clinical Psychology 73: 1599–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryle A, Golynkina K. (2000) Effectiveness of time-limited cognitive analytic therapy of borderline personality disorder: Factors associated with outcome. Psychology and Psychotherapy 73: 197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer S, Cropp C, Streeck-Fischer A. (2014) Early intervention for borderline personality disorder: Psychodynamic therapy in adolescents. Zeitschrift fur Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie 60: 368–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. (2007) Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 7: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Chiappetta L. (2019) 10-year outcome of suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 33: 82–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, et al. (2008) Can assessors and therapists predict the outcome of long-term psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder? Journal of Clinical Psychology 64: 667–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson J, Meares R. (1992) An outcome study of psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry 149: 358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffers-Winterling JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. (2012) Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012: CD005652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storebø OJ, Stoffers-Winterling JM, Völlm BA, et al. (2020) Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020: CD012955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, et al. (2014) Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: Comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. Journal of Personality Disorders 28: 734–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker L, Bauer SF, Wagner S, et al. (1987) Long-term hospital treatment of borderline patients: A descriptive outcome study. The American Journal of Psychiatry 144: 1443–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P, Mulder R, Crawford M, et al. (2010) Personality disorder: A new global perspective. World Psychiatry 9: 56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation (2021) Covidence Systematic Review Software. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Imel ZE. (2015) The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work, 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Winsper C, Bilgin A, Thompson A, et al. (2020) The prevalence of personality disorders in the community: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 216: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. (2010) The 10-year course of psychosocial functioning among patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects: Psychosocial functioning of patients with BPD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 122: 103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. (2012) Attainment and stability of sustained symptomatic remission and recovery among patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects: A 16-year prospective follow-up study. The American Journal of Psychiatry 169: 476–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-anp-10.1177_00048674211046893 for Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review by Jane Woodbridge, Michelle Townsend, Samantha Reis, Saniya Singh and Brin FS Grenyer in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Supplemental material, sj-sav-2-anp-10.1177_00048674211046893 for Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review by Jane Woodbridge, Michelle Townsend, Samantha Reis, Saniya Singh and Brin FS Grenyer in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry