Abstract

Aim:

To evaluate the client satisfaction with a phone-based antenatal care consultation and identify the associated factors during the COVID-19 pandemic at King Abdul-Aziz Medical City, Primary Health Care Center Specialized Polyclinic during 2020.

Method:

The study was a cross-sectional, retrospective study conducted with pregnant women attending the maternity clinic at the Specialized Polyclinic, Primary Health Care Center at King Abdul-Aziz Medical City, Jeddah. A self-administered questionnaire was sent via a text message (short message service) to collect the data after signed written consent.

Result:

Of 279 pregnant women, 262 (93.9%) attended phone clinic appointments one to five times. The total satisfaction level score was 73.4 ± 6.5, indicating a high level of satisfaction with the phone clinics, and 252 (90.3%) reported a high level of satisfaction. There was a significant difference in the total score regarding education, occupation, husband’s occupation, smoking, gravidity, parity, menstruation, gestational age, pregnancy complication, number of phone clinics during pregnancy, number of attending clinics during pregnancy, visiting another health facility, and reason of visiting phone clinic (p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, p = 0.015, p = 0.033, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, p = 0.027, p = 0.001, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.002).

Conclusion:

The study indicated a high level of satisfaction with the antenatal telephone clinics during the pandemic, which supports the trend of transition in the direction of the digitalization of antenatal care.

Keywords: antenatal care, COVID-19 pandemic, family medicine, patient satisfaction, telehealth, virtual

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) can be defined as “the care provided by skilled healthcare professionals to pregnant women to ensure the best health conditions for both mother and baby during pregnancy.”1,2 During these visits, various health services are done, including health promotion, screening, diagnosis, and disease prevention.1,2 With each visit, the patient’s medical history, physical examination, ordering required investigations, appropriate supplements, and medication should be assessed.

In a low-risk pregnancy, primary health care is considered the first point of care that the client needs. At the King Abdul-Aziz Medical City, Primary Health Care Center (KAMC-PHC), ANC follows a shared care protocol with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology for low-risk pregnancy. The protocol adheres to the recommendation by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), which consists of 12–14 visits. The clients are seen in-person monthly from weeks 8 to 28, then biweekly from weeks 28 to 36, and referred to the obstetrician at 36 weeks to be seen weekly until delivery.3,4

In the recent pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), health care systems were disrupted globally.5 –7 In Saudi Arabia, there was a complete lockdown for infection control purposes and overloading concerns. Caring for clients was challenging, especially for a vulnerable group such as pregnant women. Telemedicine and virtual clinics were crucial elements to maintaining continuity of care throughout this crisis.8 –10

Telemedicine refers to the care delivered to the patient through a phone-based consultation without direct physical contact with the health care system. Telehealth and telemedicine are used interchangeably; they cover a wide range of digital care services, including video consultations, mobile phone consultations, and phone-based consultations. The last include the delivery of health services through phone calls.11,12 However, in the United States, it has been used for many years to provide obstetric care, especially in rural areas. 3 In Saudi Arabia, a university hospital has been using the WhatsApp application for the past few months to facilitate communication and address non-urgent situations. 13

The most appropriate intervention to deliver health care services in Saudi Arabia during the pandemic was social distancing. The care was shifted totally from a physical to a phone base consultation. This shift in care occurred in most countries, such as Australia and Scotland. 14 To support this, the Pregnancy and COVID-19: Saudi Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SSMFM) guideline encouraged reducing the number of physical antenatal visits in low-risk populations to minimize exposure. At KAMC-PHC, ANC was delivered through a phone-based consultation by qualified family medicine physicians focused on promoting access and providing optimum care to pregnant women. All the pregnant women were booked through patient registration and given appointments according to risk factors. A special electronic form was completed. During these consultations, the clients were contacted through the registered phone number and asked about their complaints, fetal movement, vaginal bleeding, and other red flags. Investigations and obstetric ultrasound results were discussed as well. Prenatal supplements and medication were prescribed if necessary.

Client satisfaction is a significant indicator of the quality of care delivered during this pandemic. Evaluating of client satisfaction clinically matters for both health care providers and the health organization to ensure the effectiveness of the care and for the patients. As highlighted in the literature, satisfied clients are more likely to have a favorable outcome, adhere to the treatment plan, be involved with their care, and build trust with the health care system. 15 To our best knowledge, there are no local studies in Saudi Arabia addressing client satisfaction and the emergence of phone-based consultation in the antenatal clinic.

The study aimed to evaluate client satisfaction with antenatal phone-based consultation and detect the associated factors during the COVID-19 pandemic at KAMC-PHC Specialized Polyclinic from April to August 2020.

Materials and methods

The study was a cross-sectional, retrospective study conducted with the pregnant women attending the maternity clinic at the specialized polyclinic. The total number of pregnant women attending ANC from April to August 2020 was 1000. The required sample size was 278 using the Raosoft software at a 95% confidence interval (CI) level with a 50% response distribution and a margin of error of ±5%. 16

The Ethical Committee approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) was obtained with reference number (RJ20/148/J), individual written consent was obtained, and the data were kept confidential.

The list of clients booked in the maternity clinic was used for randomization. Manual systematic randomization was used to reduce bias; number 3 was the starting point, and then every second patient was included. A self-administered questionnaire using Google Forms was sent via a text message (SMS) to the sample. On the first page of the form, there is the consent form which is mandatory to complete before they can proceed to the next section. They could open the link, answer the questions, and submit the final response. Only low-risk pregnant women were included in this study who attended at least one phone-based consultation visit. High-risk pregnancies and those who did not attend any phone-based consultation were excluded.

The questionnaire was adapted from the literature.3,17 It was in English and Arabic and consisted of three parts:

Demographic data (independent variables): age, education level, marital status, occupation, monthly income, number of children, smoking, and exercise.

Obstetric information (independent variables): gestational age (GA), gravidity, parity, abortion, and chronic illness.

Satisfaction domains (dependent variables): scheduling, technology, equipment/technical issues, clinical assessment and provider, personal, general, and overall.

A pilot study was conducted with 20 pregnant women to test the questionnaire’s feasibility and applicability. The participants in the pilot study were not included in the actual research.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered and analyzed with IBM SPSS statistical software package version 21. For the qualitative variables, frequency and percentage were used for the description, and a mean value with standard deviation for the descriptive of quantitative variables and the level of satisfaction score. An independent t-test and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test were used to compare continuous variables. Statistical significance was considered at p-value < 0.05 and a confidence interval of 95% CI.

Results

Of the sample of 279, 142 (50.9%) were from 20 to 30 years, 261 (93.5%) were housewives, 192 (68.8%) were indirect smokers, and 256 (91.8%) had a monthly income from 5000 to 15,000 Saudi Riyal (Table 1). Almost a third of the cases (31.5%, n = 88) had their first pregnancy, and 99 (35.5%) reported two to three previous pregnancies, 113 (40.6%) reported one to two previous delivery, 205 (73.5%) reported no abortion, 173 (62.0%) were in the second semester, and 88 (31.5%) were in the third semester, and 178 (63.8%) had one to five children. Only 17 (6.1%) had a chronic illness, and 9 (3.2%) had complications during pregnancy. The majority (93.9%, n = 262) attended the phone clinic appointments between one and five times, 246 (88.2%) had physical visits between one and five times, and 180 (64.5%) visited another health facility between one and five times. The main reason (88.9%, n = 266) for having a phone clinic was “Mandatory from the health facility” (Table 2).

Table 1.

The study client’s demographic data.

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20–30 | 142 | 50.9 |

| Less than 20 | 16 | 5.7 | |

| More than 30 | 121 | 43.4 | |

| Education | Elementary, intermediate, high school | 217 | 77.8 |

| University, postgraduate | 58 | 20.8 | |

| Illiterate | 4 | 1.4 | |

| Occupation | Student | 5 | 1.8 |

| Housewife | 261 | 93.5 | |

| Employee | 13 | 4.7 | |

| Husband’s occupation | Student | 3 | 1.1 |

| Military | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Retired | 14 | 5.0 | |

| Employee | 261 | 93.5 | |

| Smoking | No | 85 | 30.5 |

| Ex-smoker | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Indirect smoker (in contact with smokers) | 192 | 68.8 | |

| Yes | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Monthly income (Saudi Riyal) | 5000–15,000 | 22 | 7.9 |

| Less than 5000 | 256 | 91.8 | |

| More than 15,000 | 1 | 0.4 | |

Table 2.

The study client’s medical history.

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | 2–3 | 99 | 35.5 |

| 4–5 | 54 | 19.4 | |

| More than 5 | 38 | 13.6 | |

| First time pregnant | 88 | 31.5 | |

| Abortion | 1–2 | 63 | 22.6 |

| 3–5 | 9 | 3.2 | |

| More than 5 | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Non | 205 | 73.5 | |

| Menstruation | No | 10 | 3.6 |

| Yes | 269 | 96.4 | |

| Kids number | More than 5 | 15 | 5.4 |

| Non | 86 | 30.8 | |

| 1–5 | 178 | 63.8 | |

| Pregnancy complication | Pregnancy poisoning | 1 | 0.4 |

| GDM | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Nothing | 270 | 96.8 | |

| Number of phone clinics during pregnancy | More than 5 | 7 | 2.5 |

| Non | 10 | 3.6 | |

| 1–5 | 262 | 93.9 | |

| Number of attending clinics during pregnancy | More than 5 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Non | 31 | 11.1 | |

| 1–5 | 246 | 88.2 | |

| Parity | 1–2 | 113 | 40.6 |

| 3–5 | 67 | 24.0 | |

| More than 5 | 11 | 3.9 | |

| Non | 88 | 31.5 | |

| GA (weeks) | From the first month to the third month (1–12 weeks) | 13 | 4.7 |

| From the fourth month to the sixth month (13–28 weeks) | 173 | 62.0 | |

| From the seventh month to the ninth month (29–40 weeks) | 88 | 31.5 | |

| After delivery | 5 | 1.8 | |

| Chronic illness (1) | Yes | 17 | 6.1 |

| No | 262 | 93.9 | |

| Chronic illness (2) a | HTN | 6 | 31.6 |

| DM | 3 | 15.7 | |

| Lupus | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Asthma | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 6 | 31.6 | |

| HBV | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Visiting another health facility | Non | 99 | 35.5 |

| 1–5 | 180 | 64.5 | |

| Reason for visiting phone clinic a | Pandemic lockout and curfew | 4 | 1.3 |

| Fear of transmitting infection | 27 | 9.1 | |

| Lack of transportation | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Mandatory from the health facility | 266 | 88.9 | |

GA: gestational age; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; HBV: hepatitis B virus.

Multiple responses.

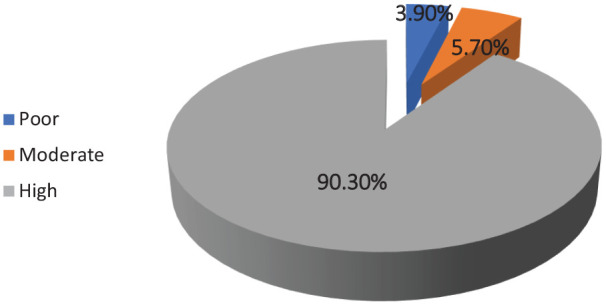

The main items to measure satisfaction were as follows: 276 (98.9%) “The quality of the call is good, and the voice was clear,” followed by 274 (98.2%) “Keeping privacy during the clinic call” and “Doctor’s behavior” equally, then 273 (97.8%) “Your doctor’s knowledge of your health,” 269 (96.4%) “Doctor’s interest in your questions and fears,” “Meet all your needs during the phone clinic,” and “Satisfaction with the telephone clinic during pregnancy follow-up” equally. Most of the participants, 266 (95.3%), reported “continue the pregnancy at this facility,” and 203 (72.7%) reported, “Recommend a telephone clinic to others during pregnancy follow-up.” (Table 3). The total level of satisfaction score was 73.4 ± 6.5, indicating a high level of satisfaction with the phone clinic, and 252 (90.3%) reported a high level of satisfaction (Figure 1 and Table 4).

Table 3.

The study client’s level of satisfaction with telehealth antenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy to have an appointment | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 51 | 18.2 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 228 | 81.7 | |

| Number of physician visits during pregnancy | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 15 | 5.4 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 264 | 94.6 | |

| Starting at the exact time of the appointment | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 20 | 7.2 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 259 | 92.8 | |

| Satisfied with the time of the next appointment | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 17 | 6.1 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 262 | 93.9 | |

| Doctor’s knowledge of your health | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 6 | 2.2 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 273 | 97.8 | |

| Consultation time | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 13 | 4.6 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 266 | 95.4 | |

| Doctor’s interest in questions and fears | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 4 | 1.5 |

| Neutral | 6 | 2.2 | |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 269 | 96.3 | |

| General evaluation of the providing services | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 4 | 1.5 |

| Neutral | 7 | 2.5 | |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 263 | 96.0 | |

| Easy to call the clinic’s phone | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 16 | 5.8 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 263 | 94.2 | |

| The quality of the call was good, and the voice was clear | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 3 | 1.1 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 276 | 98.9 | |

| The doctor’s role is clear | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 52 | 18.6 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 227 | 81.4 | |

| Doctor’s behavior | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 5 | 1.8 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 274 | 98.2 | |

| Meet all your needs during the phone clinic | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 10 | 3.6 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 269 | 96.4 | |

| Responding to concerns during the phone clinic | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 11 | 3.9 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 268 | 96.1 | |

| Keeping privacy during the clinic call | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 5 | 1.8 |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 274 | 98.2 | |

| Satisfaction with the telephone clinic during pregnancy follow-up | Strongly dissatisfied and dissatisfied | 5 | 1.8 |

| Neutral | 5 | 1.8 | |

| Strongly satisfied and satisfied | 271 | 96.4 | |

| How likely is it that you will continue your pregnancy at this facility? | Too low and low | 4 | 1.5 |

| Neutral | 9 | 3.2 | |

| Too much and much | 266 | 95.3 | |

| How likely are you to recommend a telephone clinic to others during pregnancy follow-up | Too low and low | 5 | 1.8 |

| Neutral | 71 | 25.4 | |

| Too much and much | 203 | 72.7 | |

Figure 1.

Satisfaction level category.

Table 4.

The study client’s satisfactory level with telehealth antenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic score.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Range (minimum to maximum) |

|---|---|---|

| Total score | 73.4 ± 6.5 | (34–95) |

| Variable | N | % |

| Satisfaction level category | ||

| Poor | 11 | 3.9 |

| Moderate | 16 | 5.7 |

| High | 252 | 90.3 |

SD: standard deviation.

The result showed a significant difference between the total score for education, occupation, husband’s occupation, and smoking. The group with a lower education, were housewives, and those whose husbands were retired had a significantly higher score than others (p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, and p < 0.0001). However, there was no significant difference in the age and monthly income score (Table 5). There was a significant difference between the total score and gravidity, parity, menstruation, GA, pregnancy complication, number of phone clinics during pregnancy, number of attending clinics during pregnancy, visiting another health facility, and reason for visiting phone clinic. The groups who have been pregnant more than five times (95% CI = −5.056 to −1.521, p < 0.0001), delivered more than five times (95% CI = −5.056 to −1.521, p < 0.0001), menstruated (95% CI = −5.056 to −1.521, p < 0.0001), in the second semester (95% CI = −5.056 to −1.521, p < 0.0001), who had pregnancy complications (95% CI = −5.056 to −1.521, p < 0.0001), who had more than five phone clinic visits (95% CI = −5.056 to −1.521, p < 0.0001), who visited the clinic more than five times, who had visited another health facility, and who were fearful of transmitting infection had a significantly higher score than others (p = 0.015, p = 0.033, p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, p = 0.027, p = 0.001, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.002). There was no significant difference in the total score regarding abortion, chronic illness, and the number of children (Table 6).

Table 5.

The relation between the study client’s satisfaction level with telehealth antenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic and demographic data.

| Variable | Mean | SD | p-value | 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Age (years) | 20–30 | 73.0845 | 6.26992 | 0.108 | 72.0443 | 74.1247 |

| Less than 20 | 70.8125 | 13.77543 | 63.4721 | 78.1529 | ||

| More than 30 | 74.1405 | 5.13210 | 73.2168 | 75.0642 | ||

| Education | Elementary, intermediate, high school | 74.1705 | 3.50574 | 0.0001** | 73.7014 | 74.6396 |

| University, postgraduate | 71.3276 | 9.68701 | 68.7805 | 73.8747 | ||

| Illiterate | 62.5000 | 30.98925 | 13.1892 | 111.8108 | ||

| Occupation | Student | 52.4000 | 23.64952 | 0.0001** | 23.0352 | 81.7648 |

| Housewife | 73.9387 | 4.77615 | 73.3566 | 74.5208 | ||

| Employee | 70.9231 | 10.03711 | 64.8577 | 76.9884 | ||

| Husband’s occupation | Student | 51.6667 | 27.13546 | 0.0001** | −15.7416 | 119.0749 |

| Military | 65.0000 | |||||

| Retired | 75.4286 | 5.90585 | 72.0186 | 78.8385 | ||

| Employee | 73.5862 | 5.63550 | 72.8993 | 74.2731 | ||

| Smoking | No | 71.6235 | 10.80672 | 0.0001** | 69.2926 | 73.9545 |

| Ex-smoker | 95.0000 | |||||

| Indirect smoker (in contact with smokers) | 74.0938 | 2.40017 | 73.7521 | 74.4354 | ||

| Yes | 73.0000 | |||||

| Monthly income (Saudi Riyal) | 5000–15,000 | 73.6364 | 11.49553 | 0.910 | 68.5395 | 78.7332 |

| Less than 5000 | 73.3828 | 5.92584 | 72.6534 | 74.1122 | ||

| More than 15,000 | 76.0000 | |||||

SD: standard deviation.

Table 6.

The relation between the study client’s satisfaction level with telehealth antenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic and medical history.

| Variable | Mean | SD | p-value | 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||

| Gravidity | 2–3 | 73.0306 | 5.91774 | 0.015* | 71.8442 | 74.2170 |

| 4–5 | 74.3519 | 1.75001 | 73.8742 | 74.8295 | ||

| More than 5 | 75.7895 | 6.29095 | 73.7217 | 77.8573 | ||

| First time pregnant | 72.1250 | 8.44157 | 70.3364 | 73.9136 | ||

| Parity | 1–2 | 73.2679 | 5.92594 | 0.033* | 72.1583 | 74.3774 |

| 3–5 | 73.8806 | 5.02877 | 72.6540 | 75.1072 | ||

| More than 5 | 78.2727 | 8.39155 | 72.6352 | 83.9103 | ||

| Non | 72.5227 | 7.60214 | 70.9120 | 74.1335 | ||

| Abortion | 1–2 | 74.0161 | 5.64958 | 0.421 | 72.5814 | 75.4509 |

| 3–5 | 74.7778 | 7.67753 | 68.8763 | 80.6792 | ||

| More than 5 | 76.0000 | 0.00000 | 76.0000 | 76.0000 | ||

| Non | 73.0976 | 6.69872 | 72.1751 | 74.0200 | ||

| Menstruation | No | 60.1429 | 19.80260 | 0.0001** | 41.8285 | 78.4572 |

| Yes | 74.0000 | 4.39131 | 73.4729 | 74.5271 | ||

| GA (weeks) | From the first month to the third month (1–12 weeks) | 69.0000 | 14.95549 | 0.0001** | 59.9625 | 78.0375 |

| From the fourth month to the sixth month (13–28 weeks) | 73.7283 | 4.64197 | 73.0317 | 74.4249 | ||

| From the seventh month to the ninth month (29–40 weeks) | 74.8295 | 3.81835 | 74.0205 | 75.6386 | ||

| After delivery | 49.0000 | 12.76715 | 33.1475 | 64.8525 | ||

| Kids number | More than 5 | 76.8000 | 7.53279 | 0.066 | 72.6285 | 80.9715 |

| Non | 72.6163 | 7.76443 | 70.9516 | 74.2810 | ||

| 1–5 | 73.5112 | 5.62002 | 72.6799 | 74.3425 | ||

| Chronic illness (1) | No | 73.5992 | 5.79831 | 0.059 | 72.8939 | 74.3046 |

| Yes | 70.5294 | 13.25763 | 63.7130 | 77.3459 | ||

| Pregnancy complication | No | 73.2556 | 6.45585 | 0.027* | 72.4820 | 74.0291 |

| Yes | 78.1111 | 6.33333 | 73.2429 | 82.9793 | ||

| Number of phone clinics during pregnancy | More than 5 | 80.5714 | 15.24092 | 0.001* | 66.4759 | 94.6669 |

| Non | 68.4000 | 17.25753 | 56.0547 | 80.7453 | ||

| 1–5 | 73.4122 | 5.19854 | 72.7798 | 74.0446 | ||

| Number of attended clinics during pregnancy | More than 5 | 84.0000 | 15.55635 | 0.0001** | −55.7683 | 223.7683 |

| Non | 69.8065 | 11.43800 | 65.6110 | 74.0019 | ||

| 1–5 | 73.7805 | 5.31081 | 73.1135 | 74.4474 | ||

| Visiting another health facility | Non | 72.1616 | 8.35526 | 0.017* | 70.4952 | 73.8280 |

| 1–5 | 74.1000 | 5.10022 | 73.3499 | 74.8501 | ||

| Reason for visiting phone clinic | Pandemic lockout and curfew | 60.5000 | 6.36396 | 0.002* | 3.3221 | 117.6779 |

| Fear of transmitting infection | 75.3000 | 1.33749 | 74.3432 | 76.2568 | ||

| Lack of transportation | 73.3125 | 1.53704 | 72.4935 | 74.1315 | ||

| Mandatory from the health facility | 73.3522 | 6.62109 | 72.5224 | 74.1820 | ||

SD: standard deviation.

: significant assosiation.

Regarding the study client’s satisfaction level, the multilinear regression model (enter) was statistically significant in prediction. The significant independent predictors for higher level of client’s satisfaction include educational level (95% CI = −5.056 to −1.521, p < 0.0001), having menstruation (95% CI = −11.864 to 20.007, p < 0.0001), the semester (95% CI = −2.744 to −0.452, p = 0.006), previous illness (95% CI = −2.665 to 10.117, p = 0.001), and phone clinic visit (95% CI = −5.746 to −0.095, p < 0.0001), where F = 8.445, p < 0.0001, R 2 = 0.225, and adjusted R 2 = 0.174 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Multilinear regression for potentially predictive factors of the study client’s satisfaction level with telehealth antenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| The study client’s satisfaction level | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | p-value | 95% CI for odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | Lower | Upper | ||

| (Constant) | 67.054 | 0.000 | 52.446 | 81.661 | |

| Age | 0.109 | 0.016 | 0.774 | −0.638 | 0.856 |

| Education | −3.288 | −0.232 | 0.000 | −5.056 | −1.521 |

| Occupation | −3.027 | −0.118 | 0.129 | −6.940 | 0.887 |

| Husband occupation | −2.057 | −0.124 | 0.090 | −4.435 | 0.321 |

| Smoking | 0.342 | 0.049 | 0.387 | −0.435 | 1.119 |

| Monthly income | −2.344 | −0.100 | 0.173 | −5.722 | 1.034 |

| Gravidity | −0.361 | −0.096 | 0.437 | −1.274 | 0.552 |

| Parity | −0.189 | −0.051 | 0.726 | −1.252 | 0.873 |

| Abortion | −0.100 | −0.026 | 0.651 | −0.532 | 0.333 |

| Menstruation | 15.936 | 0.631 | 0.000 | 11.864 | 20.007 |

| Semester | −1.598 | −0.144 | 0.006 | −2.744 | −0.452 |

| Children number | −1.301 | −0.119 | 0.148 | −3.066 | 0.464 |

| Chronic illness | −1.937 | −0.071 | 0.195 | −4.871 | 0.997 |

| Previous illness | 6.391 | 0.174 | 0.001 | 2.665 | 10.117 |

| Phone clinic visit | −3.772 | −0.209 | 0.000 | −5.746 | −1.797 |

| Physical clinic visit | 0.564 | 0.031 | 0.588 | −1.483 | 2.612 |

| Another health facility visit | 1.059 | 0.078 | 0.164 | −0.436 | 2.553 |

| Visit reason | −0.758 | −0.081 | 0.117 | −1.708 | 0.191 |

| R2 = 0.225 | Adjusted R2 = 0.174 | ||||

CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

Phone-based consultation has been used for decades to deliver medical care. Formerly, it has been used to reach rural areas and provide medical care to patients remotely with satisfactory results. Telemedicine technology is becoming more accessible, affordable, and routinely used by clinicians and patients. The COVID-19 pandemic has been an essential examination of the robustness of virtual care models applied in primary care.18 –21

This study showed that most pregnant women had a high level of satisfaction with the phone clinics, as 252 (90.3%) reported a high level of satisfaction. Several studies reported a high level of satisfaction with phone clinics by pregnant women. In the United Kingdom, the study by Quinn et al. 21 reported that 86% rated their experience as good or very good. Liu et al. 19 reported that women stated being very or extremely satisfied (27.9%) or moderately satisfied (43.5%) with their virtual prenatal experiences. Peahl et al. 18 reported that 77.5% of women were satisfied with doing virtual visits. Pflugeisen and Mou 3 also reported high satisfaction with virtual care. Historically, women’s acceptance of virtual care has been limited due to concerns about lack of perceived support and the long gaps between in-person visits. However, a shift in practice with the pandemic has allowed increased capture of a wider proportion of women’s preferences.21–25 Holcomb et al. 26 reported high client satisfaction with audio-only virtual ANC during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating that 99% of women felt their needs were met with virtual care and compliance with virtual clinics. In an integrative review, the authors reported that patient satisfaction and confidence in the care provided were consistently rated high, as identified through interviews and surveys covering several domains, including the ease of scheduling, interactions with health care providers, technology, and personal benefits.26 –33 Patients indicated the time and cost reductions associated with not requiring to take time off work, organize childcare, or get transportation, consistent in rural and urban settings.26 –33 This result showed that the high satisfaction levels of pregnant women regarding phone clinics are common and have been reported by several studies. 27

The response to the phone-based consultation was higher in the group in their second or third trimester or having more than one child. This is similar to other studies, and it could be related to previous pregnancy experience and other reassuring signs, such as fetal movement or a similar experience with pregnancy symptoms in the first trimester, which increased the satisfaction rate. 34 The study findings indicated that phone-based antenatal clinics were acceptable to all the patients surveyed, with significant differences regarding sociodemographic and obstetric data. In addition, the women would recommend such visits to others, which may be related to safety and decrease the time needed for physical visits and the need for transportation. Several studies reported a similar result where safety and saving time, and availability of transportation were the main reason for the perceived high level of satisfaction. 18 Holcomb et al. 26 reported that the 88% compliance with virtual clinics was significantly higher than with in-person appointments (82%; p < 0.001). A cross-sectional study by Futterman et al. 35 compared virtual with in-person appointments and found a high level of satisfaction with both, although in-person satisfaction was significantly higher. The sample agreed that they would continue to follow up the same way, and they would recommend this service to other pregnant women, similar to a Pakistani study. 36

Aziz et al. stated the importance of joining face-to-face and telemedicine approaches for high-risk pregnancies during the pandemic. We must ensure the adoption of telemedicine strategies that do not compromise feto-maternal outcomes. 37 A randomized controlled trial by Butler Tobah et al. 33 compared alternative virtual prenatal care with usual face-to-face care and reported that women had higher levels of satisfaction and less stress with the virtual care arm, with no difference in feto-maternal outcomes or perceived quality of care.

Overall, the high level of satisfaction with the phone-based ANC reported in the study demonstrated the importance of redesigning the delivery of health care and accommodating technology-based care in emergencies and as part of regular care. It requires more time in management, training, and adoption of such services in the future.

Limitations of the study

The main limitation of this study is the absence of comparison to other modalities of health care services, fetal and maternal outcomes, and the medicolegal aspects of such a service. This can limit the generalization of the results of this study. Another limitation is the mandatory use of this service during the epidemic, as there was no other option to receive the care, which could increase the satisfaction compared with no care at all.

Implications for practice and research

This study indicated that women with a low risk were satisfied in all aspects of a phone-based consultation; it is a good opportunity for policymakers and health care organizations to review the current recommendations, cost-effectiveness, medicolegal aspects, and protocols in managing such cases.

This study also calls for more detailed studies in a broader population, including a qualitative approach to highlight what could be added to the current telehealth care services from the patient’s point of view. This study was done early during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies would be needed to explore the absolute need for technology-based services to deliver other health care services in emergencies and as part of routine health care.

Conclusion

The study indicates that the most pregnant women were satisfied with receiving care via a phone-based antenatal service during the COVID-19 pandemic. It also supports potential changes to models of care that incorporate the use of telehealth. Despite sociodemographic differences, women have widely accepted virtual antenatal clinics, supporting the feasibility of virtual clinics moving forward. The study supports the combination of virtual antenatal clinics besides face-to-face delivery of care as and where convenient to ensure delivery of patient-centered care; additional exploring studies to discover suitable telemedicine strategies that aim to personalize care for pregnant women are required. For future ANC delivery, it is suggested to integrate both technology-based health care with physical attendance to ensure high-quality, evidence-based health care, and the cost-effectiveness and medicolegal aspects of the services should be measured.

Footnotes

Author contribution(s): Razaz Wali: Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Amani Alhakami: Data curation; Methodology; Writing—original draft.

Nada Alsafari: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft.

Availability of data and materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and consent to participate: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center with a reference number RJ20/148/J. Ethical principles were maintained throughout the research process. All participants signed an electronic informed consent, and confidentiality and anonymity were assured as no personal identifiers were used. All data were stored on workplace computers with access to study personnel only.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research is self-funded.

Informed consent: Written informed consent for publication was obtained.

ORCID iD: Razaz Wali  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3942-4815

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3942-4815

References

- 1. WHO. Guidelines on antenatal care (overview), 2016, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912

- 2. WHO. Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK409110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pflugeisen BM, Mou J. Patient satisfaction with virtual obstetric care. Matern Child Health J 2017; 21(7): 1544–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Academy of Pediatrics American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists. Guidelines for perinatal care. 7th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jnr BA. Use of telemedicine and virtual care for remote treatment in response to COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Syst 2020; 44: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kadir MA. Role of telemedicine in healthcare during COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Telehealth Med Today 2020; 2020: 219012713. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prasad A, Brewster R, Newman JG, et al. Optimizing your telemedicine visit during the COVID-19 pandemic: Practice guidelines for patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2020; 42(6): 1317–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Golinelli D, Boetto E, Carullo G, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic is favoring the adoption of digital technologies in health care a rapid literature review. Medrxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neubeck L, Hansen T, Jaarsma T, et al. Delivering healthcare remotely to cardiovascular patients during COVID-19: a rapid review of the evidence. Europ J Cardiovas Nurs 2020; 19: 486–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elson EC, Oermann C, Duehlmeyer S, et al. Use of telemedicine to provide clinical pharmacy services during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2020; 5: zxaa112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Field MJ; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Evaluating Clinical Applications of Telemedicine. Telemedicine: a guide to assessing telecommunications in health care, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20845554/ [PubMed]

- 12. Telehealth: The delivery of health care health education health information services via remote technologies . Waltham, MA: NEJM Catalyst, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pregnancy and COVID-19: SAUDI society of maternal-fetal medicine (SSMFM) Guidelines, https://smj.org.sa/content/41/8/779#sec-6

- 14. Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet 2020; 395(10231): 1180–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner 2010; 10(1): 38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raosoft. Sample size calculator, http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html

- 17. Fatehi F, Martin-Khan M, Smith AC, et al. Patient satisfaction with video teleconsultation in a virtual diabetes outreach clinic. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015; 17(1): 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peahl AF, Powell A, Berlin H, et al. Patient and provider perspectives of a new prenatal care model introduced in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021; 224(4): 384.e1–384.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu CH, Goyal D, Mittal L, et al. Patient satisfaction with virtual-based prenatal care: implications after the COVID-19 pandemic. Matern Child Health J 2021; 25(11): 1735–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kern-Goldberger Adina R, Srinivas SK. Obstetrical telehealth and virtual care practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2022; 65: 148–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quinn LM, Olajide O, Green M, et al. Patient and professional experiences with virtual antenatal clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic in a UK tertiary obstetric hospital: questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e25549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. mHealth. New Horizons for Health Through Mobile Technologies. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wallwiener S, Müller M, Doster A, et al. Pregnancy eHealth and mHealth: user proportions and characteristics of pregnant women using Web-based information sources-a cross-sectional study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016; 294(5): 937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Novick G. Women’s experience of prenatal care: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health 2009; 54(3): 226–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sikorski J, Wilson J, Clement S, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing two schedules of antenatal visits: the antenatal care project. BMJ 1996; 312(7030): 546–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holcomb D, Faucher MA, Bouzid J, et al. Patient perspectives on audio-only virtual prenatal visits amidst the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. Obstet Gynecol 2020; 136(2): 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu KK, Lopez C, Nichols M. Virtual visits in prenatal care: an integrative review. J Midwifery Womens Health 2021; 67: 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jeganathan S, Prasannan L, Blitz M, et al. Adherence and acceptability of telehealth appointments for high-risk obstetrical patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020; 2(4): 100233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shields AD, Wagner RK, Knutzen D, et al. Maintaining access to maternal-fetal medicine care by telemedicine during a global pandemic. J Telemed Telecare 2020; 26: 1357633X20957468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leighton C, Conroy M, Bilderback A, et al. Implementation and impact of maternal-fetal medicine telemedicine program. Am J Perinatol 2019; 36(7): 751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wyatt SN, Rhoads SJ, Green AL, et al. Maternal response to high-risk obstetric telemedicine consults when perinatal prognosis is poor. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013; 53(5): 494–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harrison TN, Sacks DA, Parry C, et al. Acceptability of virtual prenatal visits for women with gestational diabetes. Women Health Issue 2017; 27(3): 351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Butler Tobah Y, LeBlanc A, Branda ME, et al. Randomized comparison of a reduced-visit prenatal care model enhanced with remote monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 221(6): 638.e1–638.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen M, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Characteristics of online medical care consultation for pregnant women during the COVID-19 outbreak: cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020; 10(11): e043461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Futterman I, Rosenfeld E, Toaff M, et al. Addressing disparities in prenatal care via telehealth during COVID-19: prenatal satisfaction survey in East Harlem. Am J Perinatol 2021; 38(1): 88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sulaman H, Akhtar T, Naeem H, et al. Beyond COVID-19: prospect of telemedicine for obstetrics patients in Pakistan. Int J Med Inform 2021; 158: 104653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aziz A, Zork N, Aubey JJ, et al. Telehealth for high-risk pregnancies in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Perinatol 2020; 37(8): 800–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]