Abstract

Isolated choroidal melanocytosis is a rare condition that appears to be a limited form of ocular melanocytosis. Ocular melanocytosis has been known to be associated with an increased risk of uveal melanoma, and more recently, a similar association has been suggested for isolated choroidal melanocytosis. We describe 3 cases of patients who developed unilateral, multifocal uveal melanoma in the setting of underlying isolated choroidal melanocytosis. All patients developed either two distinct tumors at presentation or a new discrete choroidal melanoma arising from the choroidal melanocytosis over 1 year following treatment of the original tumor by plaque brachytherapy. These cases provide additional evidence of the association between isolated choroidal melanocytosis and uveal melanoma and suggest increased risk of multifocal melanoma in patients with this condition.

Keywords: Isolated choroidal melanocytosis, Multifocal choroidal melanoma, Choroidal melanoma, Posterior uveal melanoma

Introduction

Ocular melanocytosis is a rare but well-established congenital condition in which an excess of melanocytes in the sclera and uvea leads to increased pigmentation [1]. The term oculodermal melanocytosis, often labeled the Nevus of Ota, is used when the periocular skin is involved. Other potentially involved locations include the orbit, meninges, palate, and tympanic membrane [1]. This condition portends a 10% risk of glaucoma and a 1/400 risk of uveal melanoma in white patients [2]. One published retrospective study found the metastasis-related mortality rate of patients with primary uveal melanoma associated with ocular melanocytosis to be substantially higher than that of patients with similar tumors not associated with this condition [3]. A few case series have described 2 independent melanomas associated with ocular melanocytosis [4, 5, 6, 7, 8], and 1 case of 3 independent melanomas in the context of oculodermal melanocytosis has been reported [9]. As a result, patients with ocular melanocytosis are routinely screened for the development of uveal melanoma. Isolated choroidal melanocytosis is on the spectrum of ocular melanocytosis, but the associated risk of uveal melanoma development is not known [10, 11]. Herein, we describe 3 cases of multifocal choroidal melanomas that developed in the setting of underlying isolated choroidal melanocytosis. In 1 case, the patient presented with two distinct lesions at baseline evaluation, and in the remaining 2 cases, a second independent lesion developed after successful iodine-125 (I-125) plaque brachytherapy of the initial lesion. Written informed consents were obtained from the patients for publication of this case series and any accompanying images.

Case Reports

Case 1

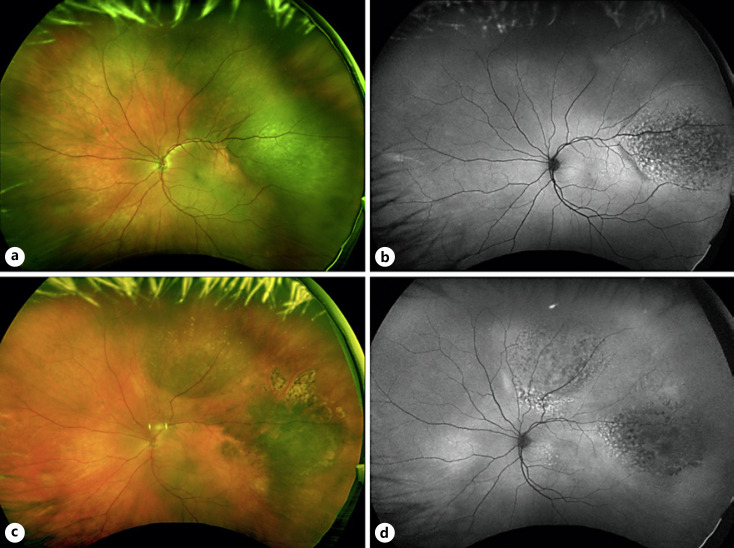

A 67-year-old white man was referred for evaluation of a choroidal mass in the left eye (OS). The patient was asymptomatic, and his last dilated examination was 6 years prior. On presentation, visual acuity was 20/30 in the right eye (OD) and 20/25 OS. The anterior segment examination was unremarkable, and fundus examination OD was normal. Fundus examination OS demonstrated a melanotic, nodular, elevated choroidal tumor measuring 13 mm × 11 mm in basal dimensions in the temporal periphery and a broad area of flat isolated choroidal melanocytosis (shown in Fig. 1a). A-scan and B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated a nodular choroidal tumor with low internal reflectivity and a maximum thickness of 4.2 mm. The tumor was diagnosed as a choroidal melanoma, and the patient subsequently underwent fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) and I-125 plaque brachytherapy. Cytopathology showed a spindle B melanoma, and gene expression profile (GEP) testing demonstrated a class 2 tumor. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) was positive.

Fig. 1.

a Widefield fundus photograph of the left eye demonstrating a darkly pigmented, nodular, elevated choroidal tumor in the temporal periphery with an underlying area of isolated flat hypermelanotic choroid consistent with choroidal melanocytosis. b Fundus autofluorescence shows diffuse overlying lipofuscin pigment. c Widefield fundus photograph of the left eye 22 months following plaque brachytherapy showing regression of the temporal lesion with a new elevated, pigmented choroidal tumor in the superior periphery arising from the choroidal melanocytosis. d Fundus autofluorescence shows prominent lipofuscin pigment along the posterior margin of the superior lesion.

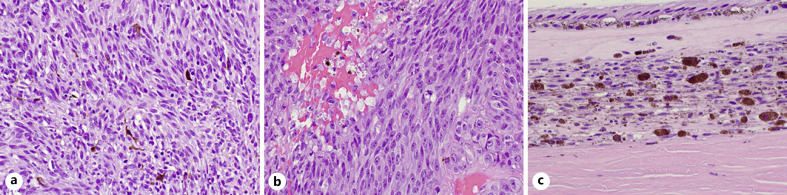

Twenty-two months following initial treatment, a new elevated, pigmented choroidal tumor in the superior periphery measuring 16 mm × 13 mm in basal dimensions was noted on clinical examination arising from the area of choroidal melanocytosis (shown in Fig. 1c). A-scan and B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated a multilobular choroidal tumor with low internal reflectivity and a maximum thickness of 3.4 mm. At this time, the original choroidal melanoma demonstrated sustained clinical regression and a thickness of 1.4 mm. The patient ultimately underwent enucleation OS, and pathology revealed two separate foci of melanoma with melanocytosis between them. The superior lesion was mixed spindle-epithelioid cell type, and GEP demonstrated a class 1A, PRAME-positive tumor (shown in Fig. 2). Next-generation sequencing demonstrated the same GNA11 mutation (p.Q209L) in the area of choroidal melanocytotis and each of the melanomas. There was no evidence of orbital recurrence or systemic metastasis 9 months after the enucleation.

Fig. 2.

a Histopathologic examination of the previously treated temporal melanoma demonstrating spindle-cell morphology (H&E, OM ×400). b Newly occurring superior melanoma demonstrating mixed (spindle and epithelioid)-cell morphology (H&E, OM. ×400). c The choroid separating the 2 foci of melanoma reveals increased benign dendritic melanocytes with plump densely pigmented polyhedral melanocytes and pigment-laden macrophages, typical for choroidal melanocytosis (H&E, OM. ×400). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; OM, original magnification.

Case 2

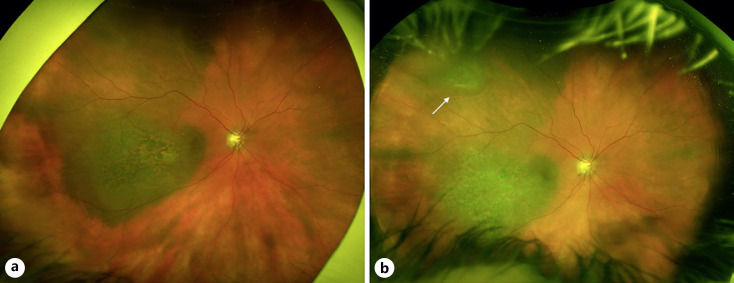

An 86-year-old white woman with a history of primary open-angle glaucoma in both eyes (OU) was referred for evaluation of a choroidal mass OD. On presentation, visual acuity was 20/40 OD and 20/30 OS. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable OU, and fundus examination OS was normal. Fundus examination OD demonstrated a darkly pigmented, nodular choroidal tumor in the temporal macula with foveal involvement. There was prominent overlying lipofuscin and surrounding subretinal fluid. The lesion measured 13 mm × 10 mm in basal dimensions, and there was a large associated area of choroidal melanocytosis superotemporally (shown in Fig. 3a). B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated a broad-based choroidal tumor with a maximal thickness of 2.0 mm. The patient was diagnosed with choroidal melanoma and underwent FNAB and I-125 plaque brachytherapy. Cytopathology was insufficient for pathologic confirmation, but GEP testing demonstrated a class 2, PRAME-positive tumor.

Fig. 3.

a Widefield fundus photograph of the right eye demonstrating a darkly pigmented choroidal tumor with prominent overlying lipofuscin and a large associated area of choroidal melanocytosis superotemporally. b Widefield fundus photograph 14 months following plaque brachytherapy showing regression of the macular lesion with a new elevated, pigmented melanoma in the superotemporal periphery arising from the choroidal melanocytosis (white arrow).

Fourteen months following initial brachytherapy, a new superotemporal choroidal tumor measuring 8 mm × 7 mm in basal dimensions within the area of isolated choroidal melanocytosis was noted on examination (shown in Fig. 3b). B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated a dome-shaped choroidal tumor with a maximum thickness of 2.0 mm. At this time, clinical examination and B-scan ultrasonography of the original choroidal tumor demonstrated a regressed temporal melanoma measuring <1 mm in thickness. The new superotemporal lesion was treated with I-125 plaque brachytherapy. On most recent follow-up, 14 months after last treatment, visual acuity was 20/30, and both treated choroidal melanomas showed evidence of appropriate regression without signs of radiation retinopathy. This case was reported prior to development of the second melanoma [11].

Case 3

A 60-year-old white woman was referred for the evaluation of a choroidal mass OD after experiencing flashes for the past month. Visual acuity was 20/30 OD and 20/20 OS. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable OU, and fundus examination OS was normal, with the exception of a small patch of myelinated retinal nerve fiber layer. Fundus examination OD showed a large area of patchy choroidal melanocytosis superiorly. Two distinct amelanotic nodules arose from the melanocytosis, with the larger one measuring 10 mm × 7 mm and the smaller one measuring 4 mm × 4 mm in basal dimensions. B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated 2 separate lesions measuring 3.4 mm and 1.6 mm in thickness, respectively, with normal choroidal thickness between them. The patient was diagnosed with multifocal choroidal melanoma in the context of underlying isolated choroidal melanocytosis and underwent I-125 plaque brachytherapy. As this patient was treated in 1998, before FNAB for cytopathologic confirmation was routinely performed in our practice and before GEP was available, cytopathology and genetic analysis were not documented for this case. On most recent follow-up, 15 years after plaque brachytherapy, both lesions demonstrated sustained regression with no evidence of local recurrence.

Discussion

Bilateral uveal melanoma has an estimated lifetime prevalence of 1 in 50 million [12], and unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma may be even more rare [13]. Most previously reported cases have occurred in the setting of ocular melanocytosis or BRCA1-associated protein 1 gene (BAP1) familial cancer syndrome. To our knowledge, none has been reported in the setting of isolated choroidal melanocytosis. In a recently reported series, 3 patients with isolated choroidal melanocytosis developed melanoma in the area of underlying melanocytosis, suggesting that similar to ocular melanocytosis, choroidal melanocytosis alone can predispose patients to melanoma [11].

Uveal melanoma development requires mutations at two distinct “nodes,” the first of which is characterized by mutually exclusive gain-of-function point mutations in members of the Gq signaling pathway (GNAQ, GNA11, CYSLTR2, and PLCB4) [14]. The second node consists of mutations in the tumor suppressor BAP1, splicing factors (most commonly SF3B1), or the translational initiation factor EIF1AX [14]. The initial mutation in the Gq pathway is noted in both nevi and melanomas and is thought to be a necessary precursor for the second mutation to occur, allowing uveal melanoma development. Durante et al. [14] demonstrated that the Gq pathway mutation can be found in the uveal melanocytes of affected portions of the uvea in ocular melanocytosis, explaining the increased risk of uveal melanoma development. In this report, an enucleated globe of a patient with a choroidal melanoma and ocular melanocytosis was assessed, and mutations in the Gq signaling pathway were noted in less than one quarter of the cells comprising melanocytosis but in 100% of the tumor cells [14]. A BAP1 mutation was detected in the tumor cells but not in the melanocytosis or the blood. This finding suggests that similar to a nevus, choroidal melanocytosis has undergone the Gq pathway mutation, creating the opportunity for second mutation development. Horgan et al. [15] assessed the cytogenetics of a ciliochoroidal melanoma in an eye with ocular melanocytosis and found regions of loss or amplification in chromosomes 3p, 3q, 1p, 8p, and 8q in melanoma cells, whereas no chromosomal abnormalities were noted within the region of melanocytosis. In the current series, next-generation sequencing was performed for case 1 and demonstrated the same mutation in the GNA11 gene common to the melanomas and the choroidal melanocytosis. This suggests that both distinct melanomas arose from the area of isolated choroidal melanocytosis and that this represents a predisposing condition for the development of uveal melanoma.

Furthermore, histopathologic assessment of the enucleated specimen in case 1 revealed increased benign dendritic melanocytes and plump densely pigmented polyhedral melanocytes, typical of uveal melanocytosis, located between the superior mixed-cell melanoma and temporal spindle-cell melanoma that had focal fibrosis and increased melanophages secondary to previous radiation treatment. The cellular morphology suggests that isolated choroidal melanocytosis appears to be a limited subtype of ocular melanocytosis. Assuming the increased risk of uveal melanoma results from the excess melanocytes that have a mutation in the Gq signaling pathway, the percentage of melanocytosis may correlate with the risk of melanoma development. Presumably, patients with isolated choroidal melanocytosis would have less risk than a patient with diffuse ocular melanocytosis but more risk than the general population. As such, patients with isolated choroidal melanocytosis should undergo regular follow-up.

It has been suggested that unilateral multifocal choroidal melanoma can represent choroidal metastases from the initial uveal melanoma [16]. Durante et al. [16] reported 4 cases of unilateral multifocal choroidal melanomas, all with class 2 GEP and identical driver mutations, in the absence of ocular melanocytosis and germline BAP1 mutations. In the current series, our patients did not undergo germline BAP1 testing as they did not have any significant personal or family history of cancer. Mutational analysis through targeted DNA was available only for case 1 in our series and, while mutations in the EIF1AX, SF3B1, and BAP1 genes could not be detected; the first tumor demonstrated GEP class 2, and the second tumor demonstrated GEP class 1A. Furthermore, the presence of isolated choroidal melanocytosis represents a predisposing factor that sufficiently justifies the occurrence of multiple separate tumors in the same eye. Isolated choroidal melanocytosis appears to be a limited form of ocular melanocytosis, increasing the risk of uveal melanoma, as well as the risk of multifocal melanoma, and warrants periodic ophthalmic evaluation.

Statement of Ethics

The study complied with the guidelines for human studies and animal welfare regulations. The subjects gave written informed consent for publication of these cases and any accompanying images. Given the retrospective and noninterventional nature of this case series, this study has been granted an exemption from requiring approval by the institute's committee on human research.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

There were no funding sources for this study.

Author Contributions

All the authors were responsible for the conception and design of the work. M.D.N., J.J.E., and B.K.W. were responsible for drafting the work, and all the authors were responsible for critical revision. The final version to be published was approved by all the authors, who agree to be responsible for all aspects of the work.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Teekhasaenee C, Ritch R, Rutnin U, Leelawongs N. Ocular findings in oculodermal melanocytosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108((8)):1114–20. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070100070037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh AD, De Potter P, Fijal BA, Shields CL, Shields JA, Elston RC. Lifetime prevalence of uveal melanoma in white patients with oculo(dermal) melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105((1)):195–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)92205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Livesey M, Walker B, Garoon R, Bucci M, et al. Association of ocular and oculodermal melanocytosis with the rate of uveal melanoma metastasis: analysis of 7872 consecutive eyes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131((8)):993–1003. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pomeranz GA, Bunt AH, Kalina RE. Multifocal choroidal melanoma in ocular melanocytosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99((5)):857–63. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010857014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honavar SG, Shields CL, Singh AD, Demirci H, Rutledge BK, Shields JA, et al. Two discrete choroidal melanomas in an eye with ocular melanocytosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47((1)):36–41. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seregard S, Ladenvall G, Kock E. Multiple melanocytic tumours in a case of ocular melanocytosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 1993;71((4)):562–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1993.tb04638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shields CL, Eagle RC, Ip MS, Marr BP, Shields JA. Two discrete uveal melanomas in a child with ocular melanocytosis. Retina. 2006;26((6)):684–7. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000236485.24808.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kheir WJ, Kim JS, Materin MA. Multiple uveal melanoma. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2020;6((5)):368–75. doi: 10.1159/000508393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fallon SJ, Shields CN, Di Nicola M. Trifocal choroidal melanoma in an eye with oculodermal melanocytosis: a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67((12)):2092–4. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_493_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augsburger JJ, Trichopoulos N, Corrêa ZM, Hershberger V. Isolated choroidal melanocytosis: a distinct clinical entity? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244((11)):1522–7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Augsburger JJ, Brooks CC, Correa ZM. Isolated choroidal melanocytosis: clinical update on 37 cases. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258((12)):2819–29. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04919-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shammas HF, Watzke RC. Bilateral choroidal melanomas. Case report and incidence. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95((4)):617–23. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450040083012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Völcker HE, Naumann GO. Multicentric primary malignant melanomas of the choroid: two separate malignant melanomas of the choroid and two uveal naevi in one eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;62((6)):408–13. doi: 10.1136/bjo.62.6.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durante MA, Field MG, Sanchez MI, Covington KR, Decatur CL, Dubovy SR, et al. Genomic evolution of uveal melanoma arising in ocular melanocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5((4)):a004051. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a004051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horgan N, Shields CL, Swanson L, Teixeira LF, Eagle RC, Jr, Ganguly A, et al. Altered chromosome expression of uveal melanoma in the setting of melanocytosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87((5)):578–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durante MA, Walter SD, Paez-Escamilla M, Tokarev J, Decatur CL, Dubovy SR, et al. Intraocular metastasis in unilateral multifocal uveal melanoma without melanocytosis or germline BAP1 mutations. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137((12)):1434–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.