Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to describe 2 patients with intraocular lens (IOL) and lens capsule spread of iridociliary melanoma.

Methods

Two pseudophakic patients with iridociliary body melanoma that spread onto the surface of their IOL and remaining lens capsule were included. Their eyes were enucleated and the histopathologic features were evaluated.

Results

Case 1 was an 82-year-old woman with diffuse primary iridociliary melanoma affecting the iris, lens capsule, IOL surface, and ciliary body. Case 2 was a 68-year-old female who developed melanoma recurrence in the anterior segment after plaque brachytherapy for iridociliary melanoma. The melanoma in both cases grew as a pigmented membrane onto the surface of the IOL.

Conclusions

IOL and lens capsule spread of iridociliary melanoma can occur primarily or develop secondarily after plaque brachytherapy of a pseudophakic eye. Since the extent of the melanoma may be uncertain and there is a high likelihood of glaucoma, enucleation is a reasonable option.

Keywords: Intraocular lens, Iridociliary melanoma, Lens capsule, Plaque brachytherapy, Uveal melanoma

Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular malignant tumor in adults. The tumor originates from the choroid, ciliary body, or iris, and comprises 5% of all melanoma diagnoses in the USA [1]. Melanomas involving the iris and ciliary body account for 10–19% of UM, while the large majority are choroidal melanomas [2, 3]. Among the types of UM, tumors localized in the iris are associated with the lowest risk for metastasis and death, while those that originate from the ciliary body and choroid have a poorer prognosis [2]. Iris melanomas may secondarily extend into the ciliary body.

Pigment deposits on the intraocular lens (IOL) and lens capsule are not unusual findings in pseudophakic eyes. However, there are a few cases reported in literature wherein pigmentation on the IOL or lens capsule was found to be metastatic cutaneous melanoma [4, 5, 6]. This series highlights 2 cases of iridociliary melanoma that extended onto an IOL and lens capsule.

Case Series

Case 1

In 2001, an 82-year-old Caucasian woman presented with decreased vision in her right eye that began several weeks prior to evaluation. She had previous cataract surgery with IOLs in both eyes. Her past medical history was pertinent for a melanoma that was removed from her left cheek 18 months earlier. Review of systems was unremarkable and systemic physical examination did not reveal any findings suggestive of metastasis. Ocular examination showed a visual acuity of counting fingers at 1 foot in her right eye and 20/40 in her left eye. Intraocular pressures (IOPs) were 31 mm Hg and 18 mm Hg in the right and left eyes, respectively. Slit-lamp examination of her right eye revealed a relatively flat, pigmented iris lesion extending from 3-o'clock to 4-o'clock from the pupillary border to the angle (Fig. 1a). A sheet of pigmented cells was seen on the anterior surface of the IOL (Fig. 1b), and the remaining anterior lens capsule. Fundus examination of both eyes showed normal findings, although view in the right eye was limited due to pigment on the IOL. No abnormal findings were seen in the left eye. Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) showed an iris mass in the right eye measuring 0.8 mm in thickness and 5.2 mm by 1.9 mm in basal diameter. A portion of the tumor in the ciliary body measured 0.6 mm thick. The patient was diagnosed with an iridociliary melanoma with spread along with the IOL and lens capsule. Treatment options were discussed, and a decision to enucleate was made. Histopathologic examination showed diffuse spread of the iris melanoma in the right eye (Fig. 2a-d). Tumor cells were seen extending along the posterior surface of the iris leaflet, crossing the peripheral anterior lens capsule and IOL optic, and invading the pupillary margin of the opposite iris leaflet. A portion of the trabecular meshwork was also invaded by tumor. The patient was referred to an oncologist for systemic surveillance but was subsequently lost to follow-up.

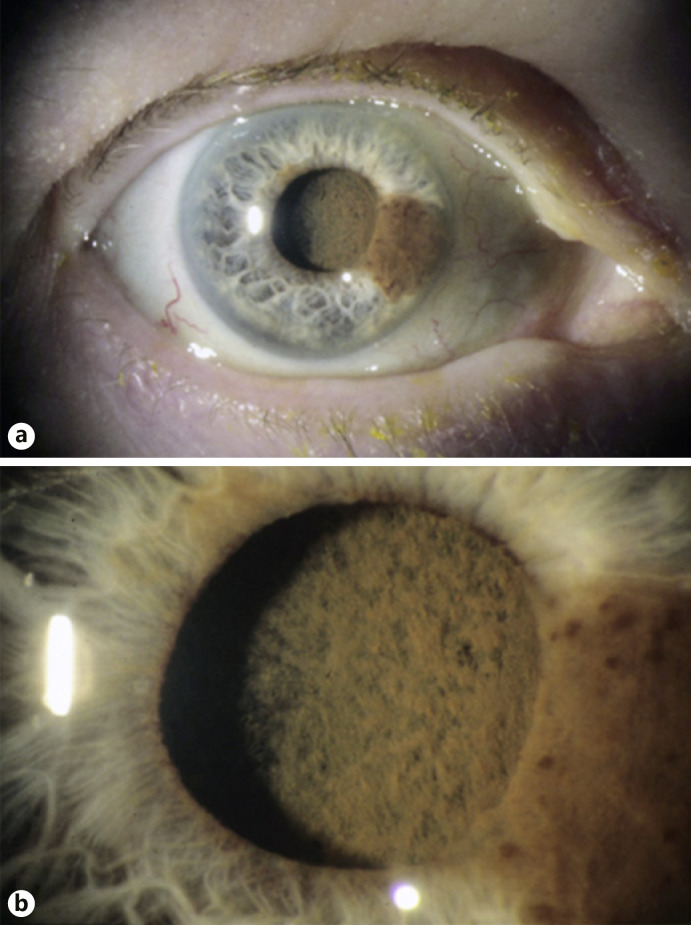

Fig. 1.

a Slit-lamp photograph of Case 1 showing an iridociliary melanoma. b Higher magnification shows dense pigmentation on the surface of the IOL.

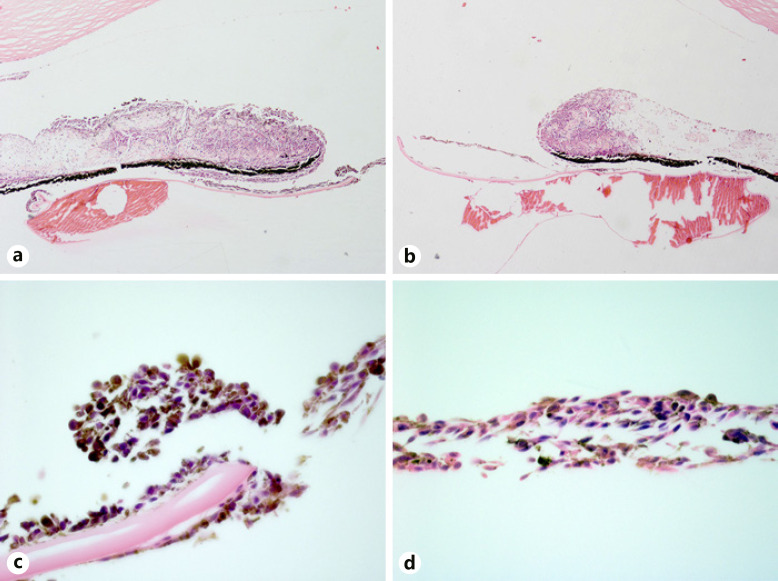

Fig. 2.

a, b Melanoma cells surround the iris leaflets. Higher magnification (×100) shows loosely coherent tumor cells on the anterior and posterior surfaces of the anterior lens capsule (c) and on the surface of the IOL (d) (hematoxylin and eosin, ×5 (a, b), ×100 (c, d)).

Case 2

A 68-year-old Caucasian woman was evaluated for left eye redness. The patient had prior cataract surgery with IOLs in both eyes. The vision in each eye was 20/20. Her IOPs were 18 mm Hg in the right eye and 40 mm Hg in the left eye. A vascularized pigmented iris lesion was present at 12-o'clock in the left eye (Fig. 3a). Gonioscopy showed increased pigmentation of the trabecular meshwork. Fundus exam was normal. No abnormal findings were seen in the right eye. On UBM, a solid iridociliary lesion in the left eye was measured to be 2.3 mm in thickness and 9.8 mm by 4.8 mm in basal diameter. The patient was diagnosed with iridociliary melanoma of the left eye and was treated with iodine-125 plaque brachytherapy (85 Gy to the apex) and topical ocular hypotensive medications. The tumor at 12-o'clock regressed and IOP fell within normal limits with topical monotherapy. On the 18th month of follow-up, the visual acuity of her left eye declined to 20/40 and IOP elevated to 32 mm Hg. Slit-lamp examination showed a regressed tumor at 12-o'clock (Fig. 3b), dense network-like pigmentation on the anterior surface of the IOL (Fig. 3c), and diffuse pigmentation of the inferior angle (Fig. 3d) which was confirmed by gonioscopy. UBM demonstrated the regressed tumor at 12-o'clock (Fig. 3e) and tumor seeding in the inferior angle (Fig. 3f). The patient was diagnosed with melanoma recurrence. After a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of treatments, the patient decided to undergo enucleation. Histopathologic examination confirmed the presence of a treated iris melanoma with no mitotic figures at 12-o'clock (Fig. 4a). Tumor cells were seen in the inferior iridocorneal angle, invading the adjacent trabecular meshwork (Fig. 4b). Lens remnants were present with tumor cells on the surface of the anterior capsule (Fig. 4c-d). The patient has not developed metastasis after 2 years from the initial diagnosis of iridociliary melanoma.

Fig. 3.

a Initial slit-lamp photograph of Case 2 shows a tumor at 12-o'clock (white arrow). b Post-plaque brachytherapy, the tumor regressed (white arrow). c A magnified view of the IOL shows a network-like configuration of pigmented cells on its anterior surface. d Illumination of the inferior angle shows a diffuse pigmented mass (black arrow). e Longitudinal UBM scan at 12-o'clock shows a regressed tumor. f Longitudinal UBM scan at 6-o'clock shows a mass in the inferior angle.

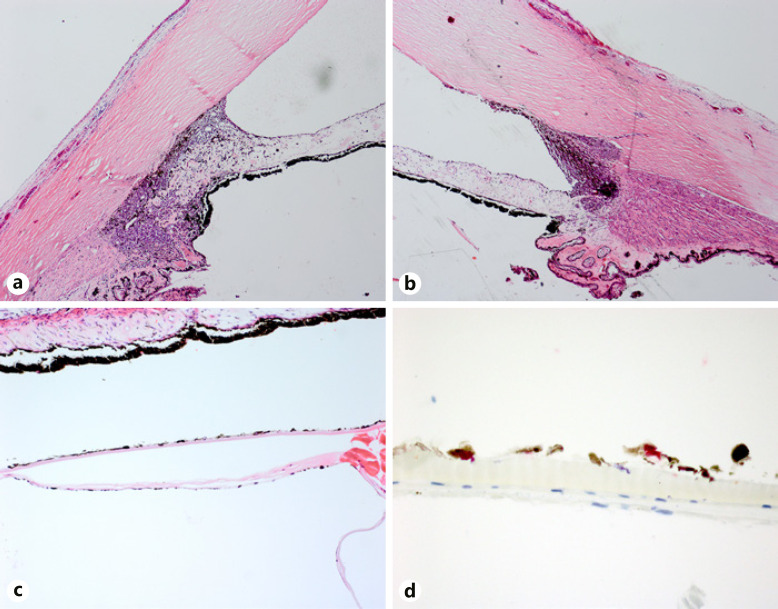

Fig. 4.

a Regressed melanoma involving the iris and ciliary body at 12-o'clock. b The inferior angle shows tumor cells on the inferior iridocorneal angle and invasion of the trabecular meshwork. c Melanoma cells are seen on the surface of the lens capsule. d Higher magnification shows the densely pigmented melanoma cells that stained positive for SOX-10 (hematoxylin and eosin, ×10 (a, b), ×25 (c); bleached and stained with SOX-10 with red chromogen, ×100 (d)).

Discussion

Features of iris melanoma that suggest aggressive behavior include large size, documented growth, prominent vascularity, ring melanoma pattern, presence of satellite lesions, and elevated IOP [7]. Iris melanomas grow along the iris surface, eventually invading the anterior chamber angle and anterior ciliary body [7], which appeared to be the case in both of our patients. Primary ciliary body tumors may present late, owing to the hidden location and distance from the visual axis. Ciliary body involvement has been associated with higher mortality, attributed to the larger size on detection and more malignant histopathologic features [8]. Increased pigmentation of the iris surface, anterior chamber angle, lens capsule, and vitreous may be observed in iris, iridociliary, or ciliary body melanoma due to deposition of pigment-laden macrophages and melanoma cells. These findings were seen in our 2 cases.

Pigment deposition on an IOL is usually an inconsequential finding in pseudophakic eyes; however, careful attention must be given in eyes diagnosed with or suspected to have UM. Increased pigmentation, especially when accompanied by network-like pigmentation on the IOL and capsular surface, may herald tumor progression or recurrence of the melanoma. This type of pigmentation is likely composed of a membrane of melanoma cells, as seen in our patients. A case of ciliary body melanoma that masqueraded as pigment dispersion glaucoma has been described in a previous report [9]. This patient also presented with fine pigmentation on the anterior lens capsule and iris, along with marked pigmentation of the trabecular meshwork. Histopathology confirmed tumor seeding in the anterior segment [9]. Increased pigmentation of the anterior segment structures including the lens capsule in a phakic eye was also observed in a 63-year-old man with metastatic cutaneous malignant melanoma [4]. In another case report, metastatic cutaneous melanoma initially presented as pigmented posterior capsule opacification in a 71-year-old woman [5]. The authors hypothesized that anterior chamber spread resulted from infiltration of the ciliary body and iris root [4, 5]. In primary iridociliary melanoma, the tumor arises from the stroma and may extend along with the lens capsule. In metastatic melanoma, melanoma cells gain access to the iris and ciliary body through its vasculature. These tumor cells may subsequently invade surrounding tissues and extend onto the lens capsule. While primary intraocular melanoma grows over an extended timeframe, metastatic melanoma arises and progresses fairly quickly.

Both patients in our report presented with elevated IOP in the affected eye. High IOP in UM develops from both angle closure and open-angle mechanisms [10]. Posterior synechiae, peripheral anterior synechiae, neovascularization, and diffuse iris melanoma result in angle closure [10]. Tumor cells and pigment-laden macrophages may obstruct the trabecular meshwork, leading to secondary open-angle glaucoma [10], which was the mechanism in our cases. IOP elevation is identified as an aggressive feature of iris melanoma [7], but it is also a known complication after plaque brachytherapy [11]. For our second case, the presence of suspicious membrane-like pigmentation on the surface of the IOL and increased pigmentation of the inferior angle supported the diagnosis of recurrent melanoma.

The presence of tumor seeds on the IOL and lens capsule should be considered when planning treatment. Plaque brachytherapy targeted to the apex of the tumor in the iris or ciliary body may not treat tumor cells posterior to the area of coverage, and a deeper target or total anterior segment irradiation may be needed. Histopathologic findings in our cases demonstrate that the tumor cells were present on the surfaces of the capsule and IOL, as well as on the posterior surfaces of the iris leaflets (Case 1) and in the ciliary body for 360° (Case 2). Since the extent of the tumor may be difficult to ascertain in these cases, enucleation is a reasonable option for similar cases.

Conclusions

This case series highlights the clinical and histopathologic features of iridociliary melanoma with extension onto the IOL surface and lens capsule in pseudophakic eyes. Pigmentation on an IOL surface and remaining lens capsule should be monitored in patients who have undergone globe-sparing treatment for iris or ciliary body melanoma. Suspected tumor seeding on the IOL, lens capsule, and the anterior chamber should be documented and considered during treatment planning.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and the need for approval was waived by the Emory University Institutional Review Board, STUDY00004321. This waiver included the waiver of the need of written informed consent from the patient to publish the case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Hans E. Grossniklaus is the Editor-in-Chief of Ocular Oncology and Pathology. Dr. Thomas Aaberg is the Chief Medical Officer of Neurotech Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Jill R. Wells and Dr. Thomas Aaberg are consultants of Castle Biosciences, Inc. Dr. Corrina P. Azarcon has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Eye Institute, NIH NEI P30 06360.

Author Contributions

Dr. Corrina P. Azarcon: concept, data collection, data analysis, original draft of the manuscript, and final draft of the manuscript. Dr. Jill R. Wells: revision of the manuscript, supervision. Dr. Thomas Aaberg: data collection, revision of the manuscript, and supervision. Dr. Hans E. Grossniklaus: concept, data collection, data analysis, revision of the manuscript, and supervision.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Chattopadhyay C, Kim DW, Gombos DS, Oba J, Qin Y, Williams MD, et al. Uveal melanoma: from diagnosis to treatment and the science in between − uveal melanoma review. Cancer. 2016 Aug;122((15)):2299–312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Furuta M, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Clinical spectrum and prognosis of uveal melanoma based on age at presentation in 8,033 cases. Retina. 2012 Jul;32((7)):1363–72. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31824d09a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh AD, Turell ME, Topham AK. Uveal melanoma: trends in incidence, treatment, and survival. Ophthalmology. 2011 Sep;118((9)):1881–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman CB, Guber D, Brown CH, Curtin VT. Cutaneous malignant melanoma with diffuse intraocular metastases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Sep;112((9)):1213. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090210097022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon JD, Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC. Posterior capsule opacity as initial manifestation of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011 Jan;249((1)):127–31. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1443-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis JH, Berry D, Abramson DH, Barker CA, Bergstrom C, Demirci H, et al. Intravitreous cutaneous metastatic melanoma in the era of checkpoint inhibition. Ophthalmology. 2020 Feb;127((2)):240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway RM, Chua WC, Qureshi C, Billson FA. Primary iris melanoma: diagnostic features and outcome of conservative surgical treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001 Jul;85((7)):848–54. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean IW, Ainbinder DJ, Gamel JW, McCurdy JB. Choroidal-ciliary body melanoma. A multivariate survival analysis of tumor location. Ophthalmology. 1995 Jul;102((7)):1060–4. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson DL, Altaweel MM, Neekhra A, Chandra SR, Albert DM. Uveal melanoma masquerading as pigment dispersion glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Jun;126((6)):868. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.6.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanoff M. Mechanisms of glaucoma in eyes with uveal malignant melanomas. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1972;12((1)):51–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karimi S, Arabi A, Shahraki T. Plaque brachytherapy in iris and iridociliary melanoma: a systematic review of efficacy and complications. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2021;13((1)):46–50. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2021.103586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.