Abstract

A method to obtain real-time measurements of the interactions between nisin and single cells of Listeria monocytogenes on a solid surface was developed. This method was based on fluorescence ratio-imaging microscopy and measurements of changes in the intracellular pH (pHi) of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester-stained cells during exposure to nisin. Immobilized cells were placed in a chamber mounted on a microscope and attached to a high-precision peristaltic pump which allowed rapid changes in the nisin concentration. In the absence of nisin, the pHi of L. monocytogenes was almost constant (approximately pH 8.0) and independent of the external pH in the pH range from 5.0 to 9.0. In the presence of nisin, dissipation of the pH gradient (ΔpH) was observed, and this dissipation was both time and nisin concentration dependent. The dissipation of ΔpH resulted in cell death, as determined by the number of CFU. In the model system which we used the immobilized cells were significantly more resistant to nisin than the planktonic cells. The kinetics of ΔpH dissipation for single cells revealed a variable lag phase depending on the nisin concentration, which was followed by a very rapid decrease in pHi within 1 to 2 min. The differences in nisin sensitivity between single cells in a L. monocytogenes population were insignificant for cells grown to the stationary phase in a liquid laboratory substrate, but differences were observed for cells grown on an agar medium under similar conditions, which resulted in some cells having increased resistance to nisin.

Food preservation techniques which include the application of bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria or purified bacteriocins have been studied extensively in order to increase the control of Listeria monocytogenes in particular in foods such as meat products and cheeses (11, 13, 14, 17, 19). The best-known and best-studied bacteriocin is the nisin produced by Lactococcus lactis (6, 9). Nisin acts on the cytoplasmic membrane of sensitive cells particularly L. monocytogenes, where it forms pores that lead to dissipation of the membrane potential and the pH gradient (ΔpH) and subsequent collapse of the proton motive force (1, 4, 27).

Most food products of interest in biopreservation are often solid or semisolid, and the probability that bacteriocins will reach the target organism depends on the nature of the food matrix. It has been shown that NaCl concentration, pH, lipid content and agar concentration affect the diffusion of different bacteriocins in an agar matrix (2). It has also been demonstrated that bacteria attached to surfaces are more resistant to disinfectants than free-living bacteria are (7, 10). Williams et al. (25, 26) concluded that an increase in the antibiotic resistance of attached Staphylococcus aureus was due to significant physiological adaptation that occurred during the early phases of attached growth.

To what extent the solid food matrix influences the probability that bacteriocins will reach the target cells and to what extent the resistance to bacteriocins is increased in surface-attached bacteria are not known. Furthermore, individual cells of a given microbial population may vary in resistance to bacteriocins. Real-time microscopic studies of the effect of bacteriocins on single cells attached to a solid surface should provide a better understanding of the actual effects of bacteriocins in solid foods. To our knowledge, direct studies of microbial interactions within solid structures have been limited to studies of microbial colonies (21).

Fluorescence ratio-imaging microscopy (FRIM) is a new technique which can be used for time-lapse studies of events, including changes in the intracellular pH (pHi) values of single bacterial cells immobilized on a solid surface, as described by Siegumfeldt et al. (20). Examination of the antimicrobial activities of bacteriocins by monitoring changes in the pHi values of target organisms as a result of damage of the cytoplasmic membrane could provide a new way to understand the interaction between bacteriocins and single bacterial cells in a food environment.

The main objective of the present work was to develop a system based on FRIM and pHi determination for real-time measurements of the interactions between bacteriocins and single bacterial cells on a solid surface. Using L. monocytogenes as the target organism, we used the system to compare the efficacy of nisin against immobilized cells with the efficacy of nisin against planktonic cells. In addition, the relationship between the dissipation of ΔpH in L. monocytogenes and the loss of viability was examined, as was the heterogeneity of nisin sensitivity in cell populations grown in a liquid substrate and on a solid substrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Experiments were carried out by using L. monocytogenes 4140 (isolated from bacon), which was provided by the Danish Meat Research Institute, Roskilde, Denmark. L. monocytogenes 11137 (isolated from cream cheese) and L. monocytogenes 11572 (isolated from cheese) were supplied by the Department of Veterinary Microbiology, The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Copenhagen, Denmark. All strains were maintained at −40°C in 20% (vol/vol) glycerol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The broth cultures were grown for 18 h at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) with the pH adjusted to 6.0 by using 5 M HCl unless indicated otherwise. Agar plate cultures of L. monocytogenes were grown on BHI agar (Difco) for 20 to 22 h at 37°C and were suspended in peptone saline (1 g of peptone per liter, 9 g of NaCl per liter; pH 6.5) to obtain a viable count of approximately 108 CFU/ml before use.

Nisin solutions.

Purified nisin, kindly supplied by Aplin and Barrett Ltd., Danisco-Cultor (Beaminster, England), was solubilized in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 10 mM glucose and was filter sterilized (pore size, 0.22 μm; GP Express membrane filter; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). A nisin stock solution (1 mg/ml, equivalent to 50 kIU/ml) was used unless indicated otherwise. Appropriate nisin solutions were prepared in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 10 mM glucose.

Staining cells for FRIM.

Using the technique described by Siegumfeldt et al. (20), we harvested the cells in BHI or peptone saline by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min and resuspended them in sterile cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 1.5 g of Na2HPO4 (Merck) per liter, 0.22 g of NaH2PO4 (Merck) per liter, and 8.5 g of NaCl (Merck) per liter (pH 7.4). The pH indicator 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (cFSE) (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) was added at a concentration of 10 μM to the cells, and the preparation was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The cell suspension was centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g, resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (Merck) (pH 5.5) containing 10 mM glucose, and energized at 30°C for 30 min. Subsequently, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min, resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 10 mM glucose, and kept on ice until microscopic analysis.

Immobilization of cells and the perfusion system.

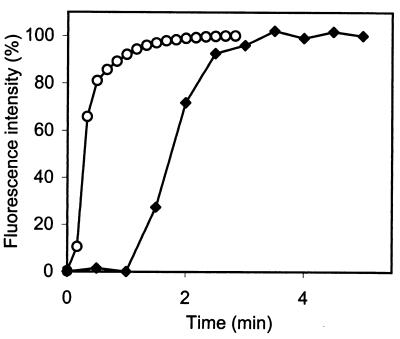

The suspension of stained cells was diluted 100-fold in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 10 mM glucose, and 100 μl was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter (type ME 25/31; Schleicher & Schuell) in order to immobilize the cells as described by Siegumfeldt et al. (20). The filter membrane (diameter, 6 mm), including cells, was mounted in a perfusion chamber (model RC-21A cell culture perfusion chamber; Warner Instrument Corp., Hemden, Conn.). The chamber was filled with 300 μl of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM) containing 10 mM glucose. Three small pieces of large-pore foam rubber (approximately, 5 by 5 by 1 mm) were placed between the pressure cab and the filter to prevent movement of the membrane filter inside the chamber. Nisin solutions were perfused through the inlet of the chamber at a rate of 9 μl/s. The perfusion was initiated at time zero by using the perfusion system described by Guldfeldt and Arneborg (8). Since nisin is not fluorescent, 5 μM fluorescein (Sigma) was used to determine the time required for exchange of solutes in the chamber. When the rate mentioned above was used, the fluorescence intensity, which was recorded in relative arbitrary units in the center of the chamber, increased with time, and after 1.5 min a constant fluorescence intensity was obtained (Fig. 1). When the filter membrane was inserted, a constant fluorescence intensity was reached after 3 min (Fig. 1). To compare the efficacy of nisin against immobilized cells and the efficacy of nisin against planktonic cells, immobilized cells were exposed to nisin solutions by perfusion through the system for a defined period of time. Planktonic cells were exposed to nisin for the same amount of time.

FIG. 1.

Increase in fluorescence intensity (wavelength, 435 nm) from time zero of perfusion through the chamber until a constant fluorescence intensity was reached when we used 5 mM fluorescein in PBS at pH 7.4 and a flow rate of 9 μl/s without the filter membrane (○) and with the filter membrane inserted in the chamber (⧫). Measurements were recorded in the center of the chamber.

Time-lapse studies of pHi values of single cells.

Time-lapse studies of pHi values were performed by ratio imaging by using a fluorescence microscope with a setup as described by Guldfeldt and Arneborg (8). This setup consisted of a monochromator equipped with a 75-W xenon lamp (Monochromator B; TILL Photonics) to excite stained cells at 490 and 435 nm with exposure times of 3 s. The inverted epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 135 TV) was equipped with a Zeiss Fluar ×100 objective (numerical aperture, 1.3), a dichroic mirror (510 nm), and an emission band pass filter (515 to 565 nm). Fluorescence emission was recorded with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (EEV 512×1024, 12-bit frame camera; Princeton Instruments). To minimize photobleaching of the stained cells, a 2.5% neutral-density filter was used (20). Ratio imaging was initiated at time zero of perfusion, and images were recorded at intervals of 1 to 5 min.

Image acquisition and calculation of pHi values.

Images were collected by using the Metafluor 3.0 software program (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, Pa.). Regions along the perimeters of the cells were drawn, and a ratio was determined by dividing the fluorescence intensity at 490 nm by the fluorescence intensity at 435 nm (R490/435) for each pixel of a cell image. In each experiment between 13 and 45 cells were analyzed. A relationship between pHi and R490/435 was established for the range from pH 5.0 to 9.0. Linear interpolation between the calibration points was carried out and used to calculate the pHi of each cell. For presentation ratio images were saved as TIF files, and Adobe Photoshop 5.5 was used for contrast enhancement.

Equilibration of pHi and pHex.

In order to equilibrate the pHi and the external pH (pHex) of cells, ethanol (63%, vol/vol) was added to stained cells to dissipate the ΔpH irreversibly. The mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min and resuspended in buffers having pH values ranging from 5.0 to 9.0. The buffers used were 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (KH2PO4-K2HPO4) for pH 5.0 to 8.0 and 50 mM sodium borate buffer (Na2B4O7 · 10H2O–0.1 M HCl; Merck) for pH 8.5 to 9.0. The ratios were determined as described above. Ratios less than 2.1 were recorded as pH 5.5.

Determination of pHi and the number of viable L. monocytogenes cells following exposure to identical nisin concentrations.

Each membrane filter with immobilized cells was removed from the perfusion chamber aseptically after exposure to nisin. The filters were vortexed thoroughly in 10 ml of sterile peptone saline water (pH 6.5). Our initial studies indicated that this was sufficient to release the cells from the membrane filters (results not shown). For each suspension 1 ml was plated directly onto three BHI agar plates, as were appropriate 10-fold dilutions in peptone saline. CFU were enumerated after incubation for 48 h at 37°C.

RESULTS

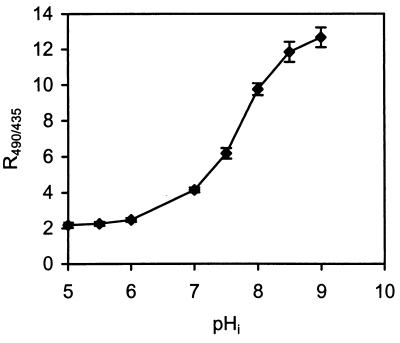

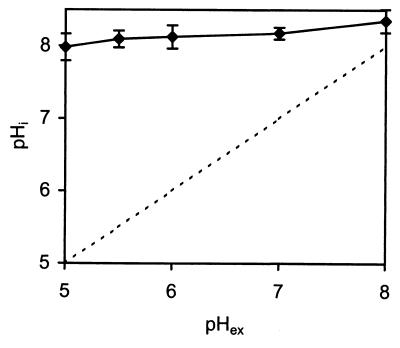

Figure 2 shows the calibration curve (R490/435 versus pHi) for ethanol-treated cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 suspended at various pH values. As Fig. 2 shows, the probe is very pH sensitive at pH 6.0 to 9.0, while values below pH 6.0 can be difficult to distinguish. Using the calibration curve, we measured the pHi values of energized L. monocytogenes 4140 cells at various pHex values ranging from 5.0 to 8.0. We found that the pHi values of L. monocytogenes cells remained almost constant value at pH 8.0 to 8.4 for pHex values ranging from 5.0 to 8.0 (Fig. 3). Since the pHi was almost constant, the ΔpH varied from 3.0 pH units at pHex 5.0 to 0.4 pH unit at pHex 8.0. For subsequent trials a pHex of 5.5 was used, which corresponds to a ΔpH of 2.6 pH units.

FIG. 2.

Relationship between R490/435 of the individual cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 and pHi. The pHi was equilibrated to pHex by incubating preparations with 63% (vol/vol) ethanol. The ratio values are averages based on 40 single cells. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

FIG. 3.

pHi values of energized L. monocytogenes 4140 cells at various pHex values. The buffer used was 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 5.0 to 8.0). The dashed line is the line for the equation pHi = pHex. The pHi values are averages based on 45 single cells. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

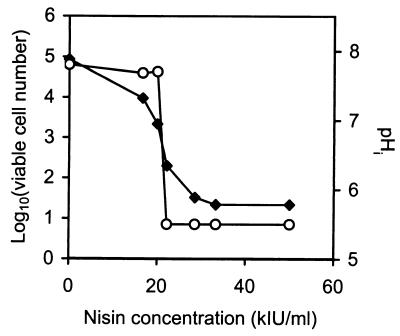

The viable cell count and pHi of L. monocytogenes 4140 were determined following exposure to identical concentrations of nisin for 12 min (Fig. 4). Figure 4 shows that the pHi remained approximately 7.9 when the nisin concentration was less than 20 kIU/ml. At higher nisin concentrations the pHi decreased to the pHex of 5.5. Compared to the pHi results, the number of viable cells started to decrease at a slightly lower nisin concentration, and eventually viability was lost when the ΔpH was dissipated.

FIG. 4.

Viable cell counts (⧫) and pHi values (○) for L. monocytogenes 4140 when it was perfused with different concentrations of nisin for 12 min at pH 5.5. The cell counts were determined based on detachment of the immobilized cells from the filter after whirl mixing in peptone saline water, plating of appropriate dilutions onto BHI agar plates, and subsequent incubation at 37°C. The ratio values are averages based on 13 to 15 single cells. The detection limit was 101 cells/ml.

The effect of nisin on L. monocytogenes 4140 immobilized on a filter membrane was compared to the effect in a liquid system (i.e., planktonic cells) (Table 1). We found that significantly lower nisin concentrations were required in the broth system to obtain membrane damage, as measured by a decrease in pHi. Exposure to nisin concentrations as low as 0.5 IU/ml for 12 min resulted in dissipation of the ΔpH for all L. monocytogenes cells in liquid cultures, whereas a concentration of approximately 50 kIU/ml was required for cells immobilized on the solid filter membrane and with the experimental setup used (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

pHi values of L. monocytogenes cells exposed to various concentrations of nisin in a broth system compared to cells immobilized on a filter membranea

| Nisin concn (IU/ml) | pHi

|

|

|---|---|---|

| In a broth system | On a filter membrane | |

| Control | 7.8 (0.5) | 7.8 (0.1) |

| 5 × 10−4 | 7.9 (0.2) | NTb |

| 5 × 10−3 | 7.9 (0.1) | NT |

| 5 × 10−2 | 6.5 (1.2) | NT |

| 5 × 10−1 | 5.7 (0.4) | NT |

| 5 × 100 | 5.5 (0.1) | NT |

| 5 × 102 | 5.5 (0.1) | NT |

| 5 × 103 | NT | 7.9 (0.1) |

| 5 × 104 | 5.6 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.0) |

The exposure time was 12 min. The values are averages (standard deviations) based on the results obtained for 30 single cells.

NT, not tested.

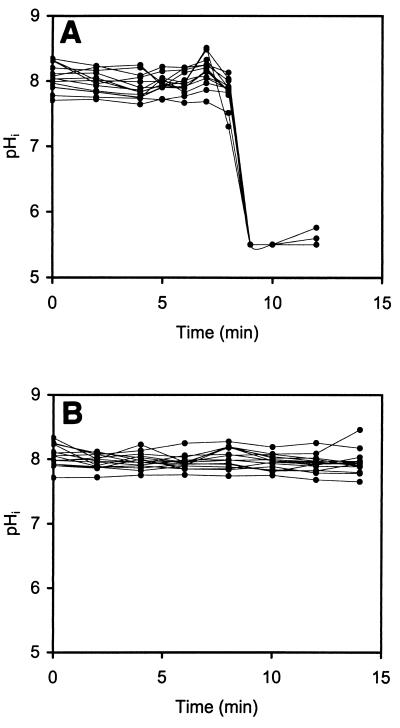

Dynamic studies on the effect of nisin on immobilized single cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 were performed. The data obtained in time-lapse studies of 15 individual cells are shown in Fig. 5. All of the cells in the stationary culture had very similar initial pHi values, about 8.0. During exposure to nisin (50 kIU/ml) at a pHex of 5.5, the pHi values of all of the cells decreased to the pHex after 9 min (Fig. 5A). In the absence of nisin the pHi values were constant during exposure to potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 10 mM glucose (Fig. 5B). Ratio images for L. monocytogenes 4140 cells at time zero and after 12 min of exposure to nisin are shown in Fig. 6A and B, respectively.

FIG. 5.

pHi values of single immobilized L. monocytogenes 4140 cells from an 18-h stationary culture as a function of time following exposure to nisin (50 kIU/ml) at pH 5.5 (A) and potassium phosphate buffer containing 10 mM glucose (pH 5.5) (B). The results for 15 individual cells are shown.

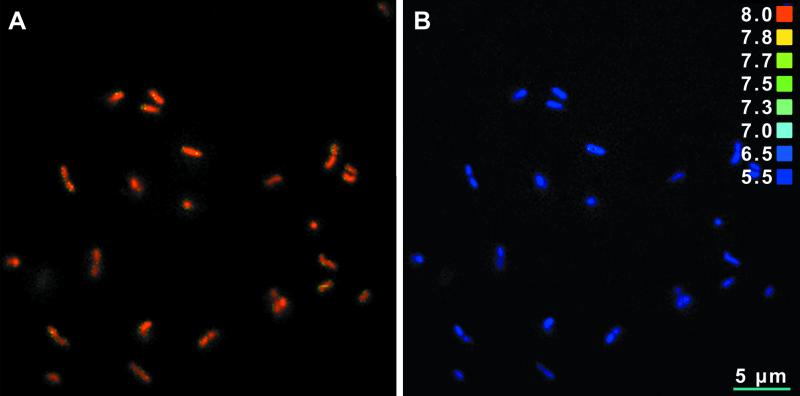

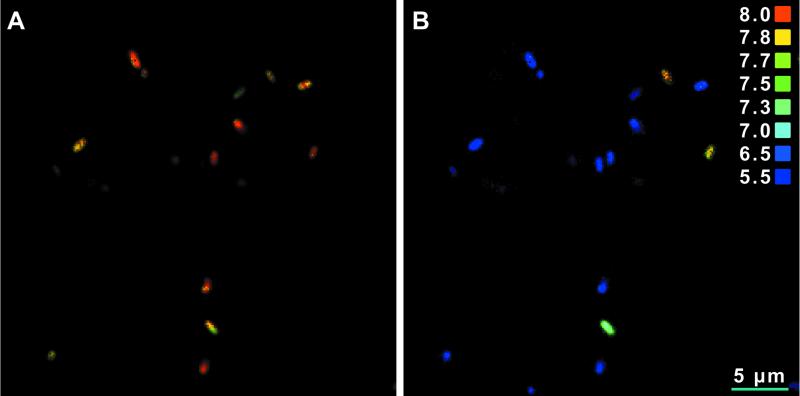

FIG. 6.

Ratio images of immobilized L. monocytogenes 4140 cells at pHex 5.5, showing the pHi of each single cell before exposure to nisin (A) and after 12 min of exposure to nisin (50 kIU/ml) at pH 5.5 (B). A color-coded pH scale is shown on the right. Ratio images were saved as TIF files, and Adobe Photoshop 5.5 was used for contrast enhancement.

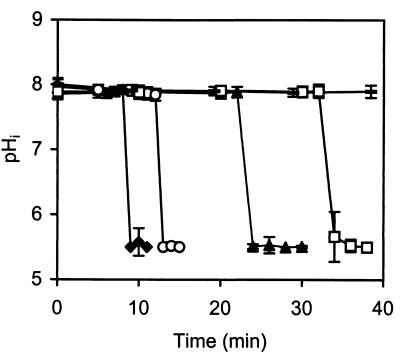

The influence of nisin concentration on dissipation of ΔpH in L. monocytogenes 4140 was also studied. The time required to obtain collapse of the ΔpH increased as the nisin concentration decreased; e.g., the time required to obtain dissipation of ΔpH increased from 9 to 34 min when a sixfold-lower concentration of nisin was used (Fig. 7). During this period the ΔpH was constant for the control. Figure 7 also shows that the rate of dissipation of the ΔpH was independent of the nisin concentration. Nisin caused the same dissipation of ΔpH for all of the cells studied regardless of the nisin concentration used.

FIG. 7.

Influence of nisin concentration (⧫, 50 kIU/ml; ○, 25 kIU/ml; ▴, 12.5 kIU/ml; □, 8.3 kIU/ml; –, control without nisin) on the time to reach dissipation of ΔpH in L. monocytogenes 4140. The pHi values are averages based on 15 single cells. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

The results obtained were verified with L. monocytogenes 11137 and L. monocytogenes 11572, and only minor differences in nisin sensitivity between the strains were observed; L. monocytogenes 11572 was the least sensitive strain (results not shown).

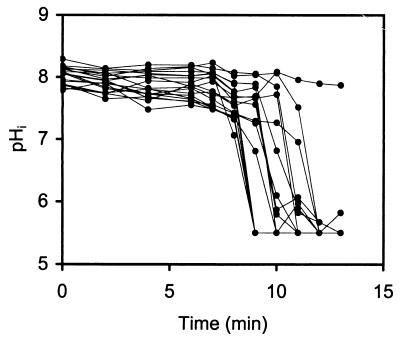

The effect of nisin on L. monocytogenes 4140 cells originating from colonies on a BHI agar plate is shown in Fig. 8. Cells previously grown on a BHI agar plate were heterogeneous with respect to sensitivity to nisin, and some of the cells appeared to be more resistant than others (Fig. 8). For the 20 cells analyzed, the time to obtain dissipation of the ΔpH varied between 9 min for the most sensitive cell to 12 min for the least sensitive cell, and one resistant cell was not affected during the 13 min of exposure. Figure 9A and B show ratio images of L. monocytogenes 4140 cells originating from colonies at time zero and after 12 min of exposure to nisin, respectively.

FIG. 8.

pHi values of 20 single cells of L. monocytogenes 4140 from colonies grown for 20 to 22 h on an agar plate at 37°C as a function of the time of exposure to nisin (50 kIU/ml) at pH 5.5.

FIG. 9.

Ratio images of immobilized L. monocytogenes 4140 cells originating from colonies grown on an agar plate. The pHi of each cell is shown at pHex 5.5 before exposure to nisin (A) and after 12 min of exposure to nisin (50 kIU/ml) at pH 5.5 (B). A color-coded pH scale is shown on the right. Ratio images were saved as TIF files, and Adobe Photoshop 5.5 was used for contrast enhancement.

DISCUSSION

Methods for describing the physiological status of food-borne contaminants on a single-cell level are required in order to predict growth and especially the duration of the lag phase of pathogens in foods, as emphasized by McMeekin et al. (15). In this context, the method described in this paper allows real-time measurements of bacteriocin-induced membrane damage of single L. monocytogenes cells on a solid matrix. Our technique includes using fluorescence microscopy and ratio imaging to perform time-lapse studies of pHi. Measuring the pHi of L. monocytogenes as a function of pHex reveals the pH homeostatic mechanism of the organism. The pHi values of L. monocytogenes cells remained relatively constant at pH 8.0 over a wide range of pHex values (pH 5 to 9). This is within the pHi range for neutrophiles (24), and in this regard the observations made in the present study are consistent with data obtained for L. monocytogenes Scott A (4) and for Listeria innocua (3, 20). However, other workers obtained lower pHi values, ranging from pH 5.44 to 6.90, depending on the pHex and on the addition of organic acids (12, 28). In all experiments carried out in the present study the ΔpH of L. monocytogenes was fully dissipated following exposure to high levels of nisin, which is consistent with previous observations (4).

While nisin was not used specifically on a food surface in this study, the information gained from our experiments may help explain why L. monocytogenes can survive exposure to nisin more easily in a complex food matrix than in a liquid system. Significantly lower nisin concentrations are needed to obtain dissipation of the ΔpH in a liquid system than in a system in which the cells are immobilized on a solid filter membrane through which the nisin has to diffuse to reach the cells. The reason for this seems not to be adsorption of nisin molecules in the system since the activity of nisin at the inlet is equal to the activity at the outlet within 2 min (unpublished data); i.e., a state of equilibrium is obtained. It has been suggested that the main reason that nisin is more inhibitory for sensitive bacteria in liquid systems than in solid and semisolid systems is the barrier functions of the nonliquid systems (16). The physical barrier of a filter membrane and slow diffusion through the filter membrane combined with the steric hindrance of the nisin molecules for attacking the cells may, therefore, explain the higher nisin concentrations required. The possibility that immobilization changes the sensitivity of L. monocytogenes to nisin cannot be eliminated. It has been demonstrated that bacteria attached to surfaces become more resistant to a disinfectant (10). Our results demonstrate that the results of in vitro experiments on the interaction between bacteriocins like nisin and bacteria in a liquid system cannot be extrapolated directly to interactions in a solid food system, as reviewed by Schillinger et al. (18).

Measurements of pHi have been used previously to study the ability of bacteriocins to inactivate pathogens like L. monocytogenes (22, 27). The previous studies were not carried out at a single-cell level but were performed with populations, and average pHi values were determined. The method which we developed to examine single cells was used to investigate the heterogeneity in a population of L. monocytogenes cells with regard to sensitivity to nisin. We found that in a population originating from a stationary broth culture grown under optimal conditions the individual cells appeared to be similar with respect to sensitivity to nisin. Heterogeneity in sensitivity to nisin among individual cells was observed with cells isolated from colonies grown on an agar plate under optimal conditions. It is likely that the heterogeneity in a colony with respect to pH and nutrient availability (23) imposes various stresses on the cells, which may change their bacteriocin sensitivities (for example, by altering the membrane composition) (5). A resistant variant of L. monocytogenes Scott A was shown to have a different phospholipid membrane composition than the nisin-sensitive parent strain (22).

In future studies the solid filter membrane in our system setup will be replaced by a matrix consisting of meat or cheese in order to verify the results with food and to determine recommended concentrations of nisin and other bacteriocins that can be used to inactivate cells of L. monocytogenes having different origins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The technical assistance of Heidi Grøn Asare is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Joss Delves-Broughton (Aplin & Barrett Ltd.) for providing the purified nisin and Henrik Siegumfeldt for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Danish FØTEK 2 program (grant 93s-2469-å95-00064) and by the Danish Bacon and Meat Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abee T, Kröckel L, Hill C. Bacteriocins: modes of action and potentials in food preservation and control of food poisoning. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;28:169–185. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blom H, Katla T, Hagen B F, Axelsson L. A model assay to demonstrate how intrinsic factors affect diffusion of bacteriocins. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;38:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breeuwer P, Drocourt J L, Rombouts F M, Abee T. A novel method for continuous determination of the intracellular pH in bacteria with the internally conjugated fluorescent probe 5 (and 6-)-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:178–183. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.178-183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruno M E, Kaiser A, Montville T J. Depletion of proton motive force by nisin in Listeria monocytogenes cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2255–2259. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2255-2259.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correa O S, Rivas E A B A J. Cellular envelopes and tolerance to acid pH in Mesorhizobium loti. Curr Microbiol. 1999;38:329–334. doi: 10.1007/pl00006812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delves-Broughton J, Blackburn P, Evans R J, Hugenholtz J. Applications of the bacteriocin, nisin. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;9:193–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00399424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhir V K, Dodd C E. Susceptibility of suspended and surface-attached Salmonella enteritidis to biocides and elevated temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1731–1738. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1731-1738.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guldfeldt L U, Arneborg N. Measurement of the effects of acetic acid and extracellular pH on intracellular pH of nonfermenting, individual Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells by fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:530–534. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.530-534.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillier A J, Davidson B E. Bacteriocins as food preservatives. Food Res Q. 1991;51:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holah J T, Higgs C, Robinson S, Worthington D, Spenceley H. A conductance-based surface disinfection test for food hygiene. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;11:255–259. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hugas M, Pages F, Garriga M, Monfort J M. Application of the bacteriocinogenic Lactobacillus sakei CTC494 to prevent growth of Listeria in fresh and cooked meat products packed with different atmospheres. Food Microbiol. 1998;15:639–650. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ita P S, Hutkins W R. Intracellular pH and survival of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A in tryptic soy broth containing acetic, lactic, citric, and hydrochloric acids. J Food Prot. 1991;54:15–19. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-54.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maisnier Patin S, Deshamps N, Tatini S R, Richard J. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in Camembert cheese made with a nisin-producing starter. Lait. 1992;72:249–263. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAuliffe O, Hill C, Ross R P. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in cottage cheese manufactured with a lacticin 3147-producing starter culture. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:251–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMeekin T A, Brown J, Krist K, Miles D, Neumeyer K, Nichols D S, Olley J, Presser K, Ratkowsky D A, Ross T, Salter M, Soontranon S. Quantitative microbiology: a basis for food safety. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:541–549. doi: 10.3201/eid0304.970419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray B. Nisin of Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis as a food biopreservative. In: Ray B, Daeschel M, editors. Food biopreservatives of microbial origin. London, United Kingdom: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 207–264. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schillinger U, Kaya M, Lücke F K. Behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes in meat and its control by a bacteriocin-producing strain of Lactobacillus sake. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70:473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schillinger U, Geisen R, Holzapfel W H. Potential of antagonistic microorganisms and bacteriocins for the biological preservation of foods. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1996;7:158–164. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schöbitz R, Zaror T, León O, Costa M. A bacteriocin from Carnobacterium piscicola for the control of Listeria monocytogenes in vacuum-packaged meat. Food Microbiol. 1999;16:249–255. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegumfeldt H, Rechinger K, Jakobsen M. Use of fluorescence ratio imaging for intracellular pH determination of individual bacterial cells in mixed cultures. Microbiology. 1999;145:1703–1709. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas L V, Wimpenny J W T, Barker G C. Spatial interactions between subsurface bacterial colonies in a model system: a territory model describing the inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by a nisin-producing lactic acid bacterium. Microbiology. 1997;143:2575–2582. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-8-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verheul A, Russell N J, Hof R R, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Modifications of membrane phospholipid composition in nisin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3451–3457. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3451-3457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker S L, Brocklehurst T F, Wimpenny J W T. The effects of growth dynamics upon pH gradient formation within and around subsurface colonies of Salmonella typhimurium. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:610–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White D. Homeostasis. In: White D, editor. The physiology and biochemistry of procaryotes. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams I, Venables A, Lloyd D, Paul F, Critchley I. The effects of adherence to silicone surfaces on antibiotic susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 1997;143:2407–2413. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams I, Paul F, Lloyd D, Jepras R, Critchley I, Newman M, Warrack J, Giokarini T, Hayes A J, Randerson P F, Venables A. Flow cytometry and other techniques show that Staphylococcus aureus undergoes significant physiological changes in the early stages of surface-attached culture. Microbiology. 1999;145:1325–1333. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winkowski K, Bruno M E C, Montville T J. Correlation of bioenergetic parameters with cell death in Listeria monocytogenes cells exposed to nisin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4186–4188. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4186-4188.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young K M, Foegeding P M. Acetic, lactic and citric acids and pH inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A and the effect on intracellular pH. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:515–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]