Abstract

Pigeons have been considered the most preferred companion for human civilizations since prehistoric times. Despite the fact that pigeons offer the most palatable and nutritious food and provide pleasure to humans, they can pose a health risk because of carrying infectious and zoonotic organisms. Moreover, the scanty of systematic reports on the occurrence of zoonotic pathogens in pigeon makes the situations worst. Hence, the current study conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the global prevalence of zoonotic pathogens among the pigeon population from existing segregated literatures. Four internationally recognized databases including Google Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, and Science Direct were used to search the published studies from January 2000 to October 2021. Analyzing the total 18,589 samples, mean prevalence estimates of pigeon pathogens worldwide were found to be 17% (95% CI:13–21) whereas serological and molecular prevalence were reported as 18% (95% CI:12–23) and 17% (95% CI:10–23). Meanwhile, virus, bacteria, and protozoal pathogens were found to be 21% (10–32%), 17% (12–23%), and 14% (10–19%), respectively. Moreover, continent wise analysis of all zoonotic pigeon pathogens has revealed the highest prevalence rate in Asia 20% (95% CI: 14–26%), followed by Europe 16% (95% CI: 08–24%), Africa 16% (95% CI: 07–24%), and America (North and South) 10% (95% CI: 03–17%). Furthermore, the highest number of studies were reported from Iran showed the prevalence rate of 20%, China 13%, Bangladesh 37%, and Poland 15%. Therefore, this prevalence of data would be helpful to the policymakers to develop appropriate intervention strategies to prevent and control diseases in their respective locations.

Keywords: Pigeon, Zoonotic pathogens, Diagnostic test, Meta-analysis, Prevalence

Graphical abstract

Pigeon; Zoonotic pathogens; Diagnostic Test; Meta-analysis; Prevalence.

1. Introduction

Pigeon farming is one of the most profitable and enjoyable businesses in the world; people have kept pigeons in their homes for personal consumption since ancient times. Pigeons are frequently used as a symbol of peace, and different countries employ them to establish diplomatic connections. However, because of their near proximity to humans and vast range of flying ability, they may be responsible for the spread of a wide range of zoonotic infections (Perez-Sancho et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2006). Moreover, the ability to adapt with various urban habitats and indoor nesting behavior favor their potential role as a source of infection for other animals and humans.

More than 110 of zoonotic diseases including deadly pathogens Campylobacter species. Coxiella burnetii, Toxoplasma species, Escherichia coli O157 and Cryptococcus species can be transferred to human through inhalation of dust and consumption of inadequately refrigerated or undercooked meat of pigeon (Haag-Wackernagel and Bircher, 2010; Dudzic et al., 2016; Sürsal et al., 2017). Furthermore, pigeon acts as the carriers of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella species, which may pose a health risk to other birds and humans (Bupasha et al., 2020). Likely, Chlamydia psittaci is the most prevalent zoonotic causal agent causes psittacosis originated from pigeons along with parrots, doves, and mynah birds.

Since pigeon have the ability to act as vector carrying zoonotic agent with high probability of pathogens transmission between humans and pigeons (Perez-Sancho et al., 2020), it is become an urgent issue to know the systematic reports regarding global magnitude of pigeon borne infections. In this regard, meta-analysis is an extremely useful statistical tool and the goal of the tools is to synthesize, integrate, and compare the findings of a huge number of primary research that look into the same issues. Moreover, the meta-analysis calculated a more precise estimate of the effect size of a specific event with better statistical power than a single research (Borenstein et al., 2021). Therefore, present research focuses on evaluating the global prevalence of the infectious zoonotic pathogens spread by the pigeons, taking into account geographical diversity. The thorough data gathered in this study will aid policymakers in developing prevention as well as control measures.

2. Methodology

The current study quantitatively summarized and compared the prevalence of zoonotic pathogens from pigeon globally. At first systematic review was performed followed by data extraction and conducted meta-analysis, which compiled last 21 years' time series data for analyzing the pooled prevalence with risk factors.

2.1. The study protocol and literature search strategy

The current systematic study focuses on calculating the prevalence of zoonotic pathogens from pigeon birds using the PRISMA standards for systematic review and meta-analysis (http://www.prisma-statement.org). Thus, a systematic literature search between the years 2000–2021 was conducted using a combination of keywords such as ‘pigeon, ‘zoonotic pathogens and ‘prevalence’ in globally recognized four electronic databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct and Scopus; meanwhile, for obtaining the various country's studies, the database was scrutinized randomly. Besides, additional studies were gathered by manually searching the cross references or bibliographies section of eligible studies and finally, the eligible studies were extracted by two reviewers (MMM and MH) for eliminating the bias. In the case of disagreement, a third reviewer (MRH) assessed the article in question to determine its relevance. The agreement was reached by group discussion with a third reviewer.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

The current meta-analysis covered all original descriptive studies published in the English language that explored the prevalence of zoonotic pathogens aroused from pigeon birds. The studies those were confirmed by (polymerase chain reaction) PCR, (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) ELISA, (hemagglutination inhibition) HI, and (hemagglutination assay) HA, latex agglutination, modified agglutination tests were included for current meta-analysis. The studies which were synthesized from 2000 to 2021 and only from domestic pigeons were included.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Review articles, duplicates, qualitative studies, case reports, case series, and studies published in non-peer reviewed journals were excluded. Moreover, the studies those were not confirmed by PCR, ELISA, HI, and HA tests were excluded for current meta-analysis. Identified the zoonotic pathogens from wild pigeons were excluded.

2.4. Quality assessment

A predefined rating system was used to measure the quality of various studies to accurately judging study type and minimizing the bias of selected studies (Kuralayanapalya et al., 2019; Patil et al., 2021). The rating was on a scale of 0–5, with each part receiving the maximum of two stars. For calculating the score, the author's name with the study year, utilized representative sample, comparability, exposure ascertain, and result were taken in the consideration. Thus, the total quality rating score was confined between 3 and 4 (Supplementary Table 1).

2.5. Screening and data extraction

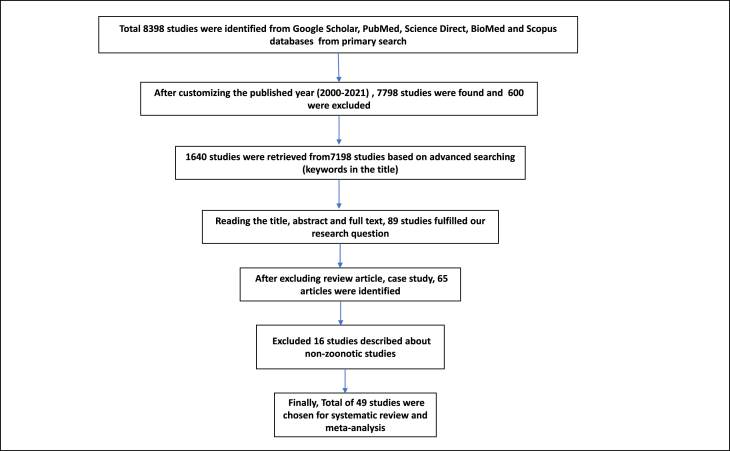

The information was gathered from qualified studies that included the name of first author, published year, location of study, total sample size, detection or diagnostic test, and kind of pathogens like bacterial, viral or protozoal. In this study, individual zoonotic pathogens obtained from pigeon around the world were used to categorize as a parameter; besides, continent-by-continent and country-by-country stratification of studies was undertaken. Then, each selected study was double-checked to rule out any possible consensus, and all the relevant data were extracted from the eligible studies; the study selection steps were visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the procedures of choosing eligible studies.

2.6. Assessment of bias, data preparation, and analysis

The Jamvoi software (version 1.2.27, https://www.jamovi.org) was used to conduct the meta-analysis. This study enables the generation of a weighted average percentage of prevalence from numerous studies, paving the path for optimal planning. The statistical analysis was carried out using meta-analysis (Major) packages. The percentage of variation owing to heterogeneity among the numerous reports included in this study was calculated using the tau2, I2 (Higgin's I2), and p value. Moreover, the pooled prevalence of individual pathogens was calculated using the fixed and random effect model because of expecting significant variability. Furthermore, displaying the Standard Error (SE) of each study, the funnel plot was created with the y-axis and the x-axis was used to show the effect of each study. Consequently, representing the publication bias by presenting the non-symmetrical shape of a funnel with dropping the points exterior to the funnel. Whenever the publication bias is practically negligible, studies with high precision concentrate along with the typical line, and those with low accuracy disperse consistently on both side of the median line, resulting in a funnel-shaped scatter (Egger et al., 1997). Forest Plot was used to visualize the data graphically. For calculating the result, the limited maximum-likelihood estimation has been used to establish the relationship between prevalence estimates and variance of study, which were presented as a percentage with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Finally, subgroup analysis was carried out based on the species affected, the type of pathogens, the method of diagnostic test, continents of the world, and the countries to evaluate the heterogeneity in each group and their comparison.

3. Results

In the present study, a systematic review of scientific publications on the prevalence of zoonotic pigeon pathogens was conducted for 21 years (2000–2021). Studies regarding the prevalence of zoonotic pathogen from pigeon were rigorously screened, and irrelevant studies were removed. A number of 49 studies came from Europe, Asia, Africa, South America, and North America were chosen for systematic review and meta-analysis in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Authors name and year | Representativeness of the sample | Diagnostic method |

|---|---|---|

| (Stenzel et al., 2014) | Cloacal and pharyngeal swabs | TaqMan Real-Time PCR Screening |

| (Al-abodi, 2017) | Blood samples | Conventional PCR |

| (Altamimi, 2020) | Faecal samples | Nested PCR |

| (Saifullah et al., 2016) | Cloacal swabs, pharyngeal swabs | PCR |

| (Dolz et al., 2013) | Fecal sample | Nested PCR |

| (Mahzounieh et al., 2020) | Cloacal swab samples, | PCR |

| (Geigenfeind et al., 2012) | Pharyngeal and cloacal samples | Nested PCR |

| (Dickx et al., 2010) | Pharyngeal swabs | Nested PCR |

| (Gargiulo et al., 2014) | Cloacal swab | PCR |

| (Ibrahim et al., 2018) | Blood and tissue samples | ELISA |

| (Tsai et al., 2006) | Blood serum samples | Latex agglutination test (LAT) |

| (Parmentier et al., 2019) | Muscle biopsies | DNA by semi-nested PCR |

| (Doosti et al., 2014) | Blood samples | PCR |

| (Akbarmehr, 2010) | Intestine, spleen and liver | PCR |

| (Cano-Terriza et al., 2015) | Blood samples | Blocking ELISA |

| (Zhang et al., 2019) | Blood samples | Indirect hemagglutination assay |

| (Pekmezci et al., 2021) | Droppings | Nested PCR |

| (Koompapong et al., 2014) | Feces | PCR |

| (Ghorbanpoor et al., 2015) | Pharyngeal swabs | PCR |

| (Perez-Sancho et al., 2020) | Samples from intestine | PCR |

| (Cong et al., 2013) | Blood samples | Indirect Haemagglutination assay |

| (Kaczorek-Łukowska et al., 2021) | Cloaca, crop and faeces of birds | PCR |

| (Radimersky et al., 2010) | Cloacal swabs | PCR |

| (Golestani et al., 2020) | Pharyngeal swab | Nested PCR |

| (Mattmann et al., 2019) | Choanal-cloacal swabs, liver samples | Real-time PCR |

| (Helen Owoya et al., 2020) | Blood sample | Haemagglutination inhibition test |

| (Esameili et al., 2015) | Cloacal sample | Multiplex PCR |

| (Bupasha et al., 2020) | Cloacal swab | PCR |

| (Salant et al., 2009) | Blood sample | Modified Agglutination Test |

| (Ballmann and Harrach, 2016) | Dead or alive, healthy pigeons | Nested PCR |

| (Cong et al., 2012) | Blood sample | Modified agglutination test |

| (Elina et al., 2017) | Blood sample | Hemagglutination Inhibition |

| (González-Acuña et al., 2007) | Blood, organs and intestine contents | Commercial Elisa kit |

| (De Lima et al., 2011) | Cloacal and tracheal swabs | Hemi-nested PCR |

| (Ebani et al., 2016) | Spleen samples | PCR |

| (Silva et al., 2009) | Fresh feces samples | Multiplex PCR |

| (Dudzic et al., 2016b) | Cloacal swabs | PCR |

| (Jahantigh and Nili, 2010) | Pigeon eggs | PCR |

| (Karim et al., 2020) | Oral and cloacal; swabs | PCR |

| (Yan et al., 2011) | Blood samples | Modified agglutination test |

| (Bahrami et al., 2016) | Blood samples | Neospora Agglutination test (NAT) and PCR |

| (Jonassen et al., 2005) | Cloacal swab samples | RT-PCR |

| (Tanaka et al., 2005) | Faecal samples | PCR |

| (Tsai and Lee, 2006) | Blood samples | Haemagglutination inhibition test |

| (Ibrahim et al., 2021) | Blood samples | Haemagglutination inhibition test |

| (Zhuang et al., 2020) | Swab and feces sample | Conserved RT-PCR assay |

| (Vučemilo et al., 2003) | Cloacal swabs | Haemagglutination inhibition |

| (Gronesová et al., 2009) | Oropharynx and cloaca | Nested RT-PCR |

| (Mohammadi et al., 2010) | Blood sample | Haemagglutination inhibition |

3.1. Estimated pooled prevalence of pathogens

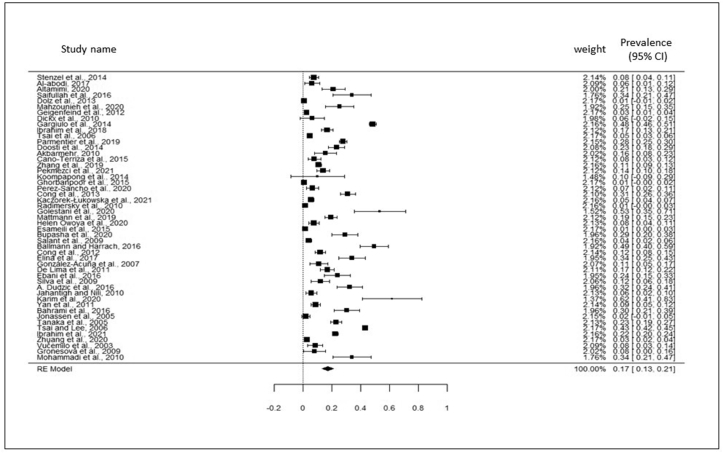

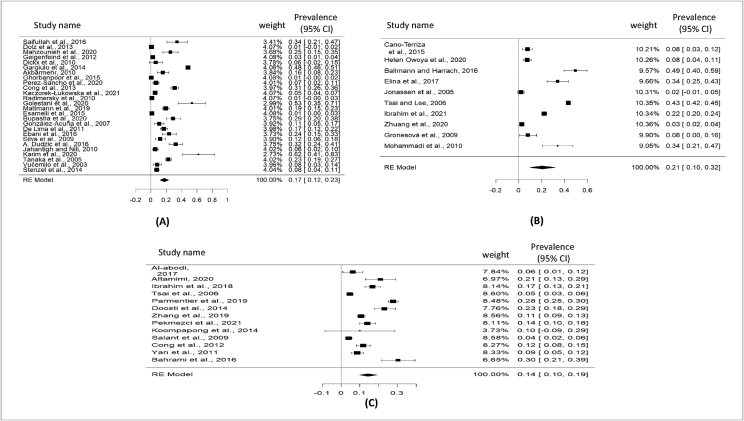

Total selected 49 studies were obtained from Asia (8 countries), Europe (11 countries), North America and South America (3 countries), Africa (2 countries), and Eurasia (Turkey) regions (Table 2). The current meta-analysis analyzed a total of 18,589 samples from the years January 2000 to October 2021, and revealed that the global prevalence of pigeon-borne zoonotic pathogens was 17% (95% CI: 13–21%) (Figure 2); besides funnel plot of all the studies was showed in Figure 3. Subsequent that, analyzing the continent-wise result of all zoonotic pathogens from pigeon (Figure 4), the highest prevalence rate was found in Asia 20% (95% CI: 14–26%), followed by Europe 16% (95% CI: 08–24%), Africa 16% (95% CI: 07–24%), and America (North and South) 10% (95% CI: 03–17%) (Figure 5) (Table 2). Finally analyzing the result based on test procedure, PCR (molecular method) showed 18% (95% CI: 12–23%) prevalence rate (Figure 6) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Continent wise zoonotic diseases’ prevalence from pigeon bird.

| Region/Continent with total prevalence | Country | Infection/Disease(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Asia (20%) 95% CI: (14–26) % No. of Studies: (25) |

Iraq, Bangladesh, Iran, Taiwan, China, Thailand, Israel, Japan, Taiwan |

Cryptosporidium meleagridis, Salmonella species, Chlamydia psittaci, Toxoplasma gondii Haemoproteus columbae, Toxoplasma gondii, Escherichia coli O, Newcastle Disease Virus, Neospora caninum, Chlamydia pecorum, Newcastle disease, Coronaviruses (CoVs), Avian influenza. |

| Europe (16%) (95% CI: 08–24) No. of Studies: (16) |

Poland, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Spain, Czech Republic, Hungary, Norway, Croatia, Slovak Republic | Chlamydia psittaci, Campylobactor jejuni, Sarcocystis calchasi, flaviviruses of the Japanese Encephalitis antigenic complex (JEV), Salmonella species, Escherichia coli, Adenovirus, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Bartonella species, Coxiella burnetii, Rickettsia species, Chlamydophila species), Coronaviruses, Avian influenza A |

| Africa (16%) (95% CI: 07–24) No. of Studies: (3) |

Egypt, Nigeria | Toxoplasma gondii, Newcastle disease virus (NDV) |

| North and South America (10% (95% CI: 03–17) No. of Studies: (4) |

Costa Rica, Chile, Brazil |

Chlamydia psittaci, Chlamydophila psittaci, Escherichia coli, |

Figure 2.

Visualizing forest plot described pooled prevalence of zoonotic diseases from pigeon.

Figure 3.

Graphically representation of funnel plot described studies heterogenicity.

Figure 4.

Forest plot for representation of continent wise prevalence; A) Asia; B) Europe; C) North and South America; and D) Africa

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of continent wise prevalence in world map.

Figure 6.

PCR based pooled prevalence.

Table 3.

Prevalence of zoonotic diseases from pigeon based on different diagnostic tests.

| Diagnostic test | Random effect model |

Fixed model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | I2 (%) | H2 | Tau2 | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | |

| PCR (Molecular) | 34 | 18 (12–23) | 99.18 | 122.4 | 0.022 | 06 (06–07) |

| ELISA/Agglutination test/Haemagglutination assay/Haemagglutination inhibition (Serological) | 15 | 17 (10–23) | 98.66 | 74.6 | 0.014 | 17 (16–17) |

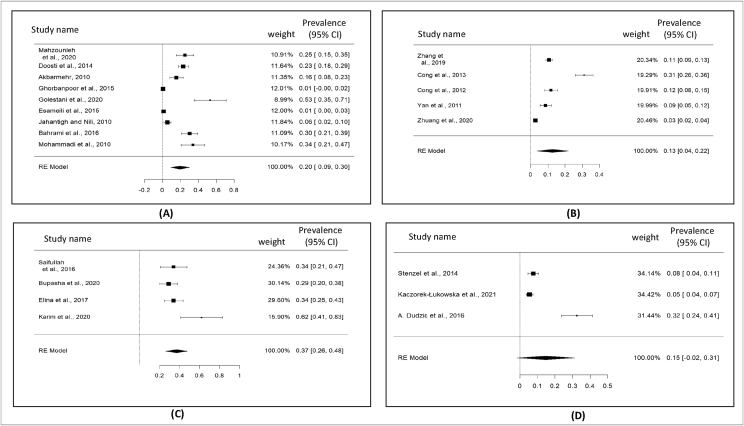

3.2. Country wise prevalence

In case of country wise prevalence among the European countries from multiple studies, the prevalence rate 15% (95% CI: -02–31%) was found in Poland; whereas, 36%, 11%, and 7.5% prevalence rate were found in Spain, Italy, and Switzerland, respectively. Similarly, single study from Hungary, Germany, Croatia, Belgium, and Czech Republic reported 49%, 28%, 8%, 6%, and 1% prevalence rate, respectively. In contrast, among the Asian countries, the pooled prevalence was found to be 37% (95% CI: 26–48%) in Bangladesh (Figure 7), 20% (95% CI: 09–30%) in Iran, and 13% (95% CI: 04–22%) in China. Likely, two studies individually from Taiwan, and Iraq reported 24% and 13.5% prevalence rate, correspondingly. Besides, single study from Japan, Thailand and Israel reported 23%, 10%, and 4% prevalence rate. However, the maximum prevalence was reported as 17% in Egypt; meanwhile, 15% prevalence was found in Nigeria among the African countries. Among the American countries (North and south), 14.5% prevalence rate was reported from Brazil; whereas, Chile and Costa Rica reported 11% and 1% prevalence rate (Table 4).

Figure 7.

Forest plot for representation of country wise prevalence; A) Iran; B) China; C) Bangladesh; and D) Poland.

Table 4.

Country wise disease prevalence with causal agent.

| Country | Type of causal agent | Random effect model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | I2 (%) | H2 | Tau2 | ||

| Iran |

Chlamydia psittaci Haemoproteus columbae Salmonella species Chlamydophila psittaci Chlamydia psittaci Escherichia coli Neospora caninum Avian influenza |

09 | 20 (09–30) | 99.11 | 111.9 | 0.024 |

| Chin |

Toxoplasma gondii Chlamydia psittaci Coronaviruses (CoVs) |

05 | 13 (04–22) | 98.56 | 69.2 | 0.010 |

| Bangladesh |

Salmonella species Newcastle Disease Virus Escherichia coli |

04 | 37 (26–48) | 69.81 | 3.3 | 0.008 |

| Poland |

Chlamydia psittaci Salmonella species Campylobacter species |

03 | 15 (-02–31) | 98.54 | 68.2 | 0.020 |

3.3. Bacterial, viral and protozoal pathogens’ prevalence

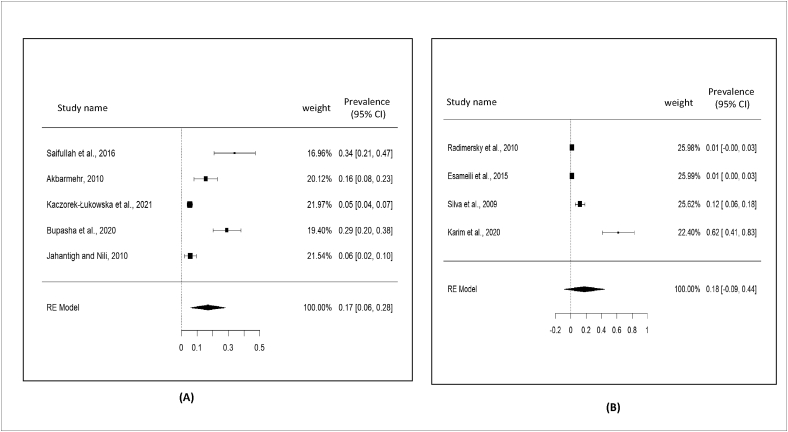

Among the bacterial pathogens, Campylobacter species showed comparatively higher prevalence in pigeon 24% (95%CI: 04–44%), whereas Escherichia coli showed prevalence rate of 18% (95%CI: –09–44%). Similarly, Chlamydia psittaci revealed the prevalence rate of 17% (95%CI: 09–26%) and Salmonella species reported 17% (95% CI: 06–28%) (Figure 8). In conjunction, prevalence of Chlamydophila psittaci and tick-borne bacteria (Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Bartonella species, Coxiella burnetii, Rickettsia species, Chlamydophila species) was found to be 6% and 24%, respectively. However, a total of 26 studies on bacterial zoonotic pathogens from pigeon reported a prevalence of 17% (95% CI: 12–23%) with heterogeneity I2 = 99.2%, Tau2 value was 0.022, p < 0.001 (Figure 9) (Table 5).

Figure 8.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence rate based on causal agent; A) Salmonella spp.; B) Escherichia coli.

Figure 9.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of diseases; A) Bacterial; B) Viral; and C) Protozoal.

Table 5.

Prevalence viral, bacterial, and protozoal zoonotic disease from pigeon.

| Type of causal agent | Random effect model |

Fixed model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | I2 (%) | H2 | Tau2 | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | |

| Virus | 10 | 21 (10–32) | 99.35 | 153.17 | 0.030 | 17 (16–17) |

| Bacteria | 26 | 17 (12–23) | 99.22 | 128.92 | 0.022 | 06 (05–06) |

| Protozoa | 13 | 14 (10–19) | 96.50 | 28.53 | 0.006 | 10 (09–11) |

Moreover, Pigeon birds are the potential stake holders for the spreading of viral zoonoses by variety of medium. The prevalence of overall viral zoonotic pathogens from pigeon was 21% (95% CI: 10–32%), I2: 99.35%, Tau2 value: 0.030, p < 0.001, which is highest among the zoonotic agents; meanwhile, studies on Newcastle disease virus infection revealed a prevalence of 27% (95% CI: 11–42) globally (Figure 10). Similarly, Coronaviruses (CoVs) and avian influenza were found to be 25% and 21%, respectively. A single study on Japanese encephalitis from India showed 8% (95%CI: 03–12%) prevalence rate.

Figure 10.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence rate based on causal agent; A) Chlamydia psittaci; B) Toxoplasma gondii; C) Campylobacter spp., and D) Newcastle Disease Virus.

Furthermore, thirteen studies on zoonotic protozoal pathogen of pigeon were selected in this study. The overall prevalence was reported 14% (95% CI: 10–19%), I2: 96.50%, Tau2 value: 0.030, <0.001); whereas, Toxoplasma gondii was found to be 7% (95% CI: 06–12%) (Figure 8) (Table 6). Likely, the reported prevalence of the single study on three protozoa was 14% (95% CI: 10–18%) for Enterocytozoon bieneus, 23% (95% CI: 18–29%) for Haemoproteus columbae, and 30% (21–39%) for Neospora caninum. During the last decades, pigeon populations have increased exponentially in different countries, reaching densities higher than 2000 birds/km2 in many European cities and may cause a serious threat because of carrying zoonotic infectious pathogen (Cano-Terriza et al., 2015; Patil et al., 2021).

Table 6.

Prevalence of zoonotic diseases categorized by causal agent.

| Type of causal agent | Random effect model |

Fixed model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | I2 (%) | H2 | Tau2 | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | |

| Campylobacter species | 04 | 24 (04–44) | 98.79 | 82.89 | 0.040 | 35 (33–36) |

| Chlamydia psittaci | 10 | 17 (09–26) | 98.76 | 80.37 | 0.018 | 05 (05–06) |

| Escherichia coli | 04 | 18 (-09–44) | 99.77 | 428.91 | 0.069 | 02 (01–02) |

| Newcastle Disease | 04 | 27 (11–42) | 99.20 | 124.86 | 0.023 | 33 (32–34) |

| Salmonella species | 05 | 17 (06–28) | 95.98 | 24.88 | 0.014 | 07 (06–09) |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 07 | 09 (06–12) | 91.47 | 11.72 | 0.001 | 07 (06–08) |

4. Discussion

Pigeons, as a sociable bird, remain closer to humans, perhaps posing health risks due to the presence of infectious and zoonotic pathogens. A systematic comprehensive data about the occurrence of zoonotic diseases in pigeon is important to take the proper interventional measures. Analyzing the results, mean prevalence of zoonotic pathogens was found 17%; meanwhile, Asian region reported 24% prevalence rate followed by Africa and Europe 16% and North with South American continent 10%. Frequent contact with pigeons, popularity of pigeon games in Middle East countries (PCRC, 2021), poor hygiene practices in developing countries specially in Asia could be the possible reason for comparatively higher prevalence in Asian region. More specifically, analyzing multiple studies among Asian countries, Bangladesh possesses comparatively higher prevalence rate than others; meanwhile, the prevalence rate in China and Iran was in moderate level. Pigeons are sold in the small and large live bird markets associated with chicken and ducks in Bangladesh, which create huge public gatherings at live bird markets with unhygienic environments may favor the maximum transmission of infectious agent from bird to bird and bird to human (Dey et al., 2013). In contrast, result from the multiple studies of each country within the European region, Spain and Poland reported higher susceptibility to zoonotic pigeon born pathogen. Likely, from African and American region, maximum prevalence rate was recorded in Egypt and Brazil, respectively. Dissimilarly, single study was reported from Hungary, Germany, Croatia, Belgium, Czech Republic Japan, Thailand, Israel, Chile and Costa Rica, whereas Hungry possessed the highest prevalence rate.

From our analysis, it is concluded that viral pathogen (21%) is predominant than bacterial pathogen (17%) and protozoan pathogen (14%). This reason could be due to the robust disease reporting system available globally (Patil et al., 2021). Among the viral pathogen, Newcastle virus, Corona viruses (CoVs) and avian influenza were found more prevalent and recent study reported that, outbreaks of avian influenza continue to be a global public health concern due to ongoing circulation of various strains (H5N1, H5N2, H5N8, and H7N8), (O1E, 2021). On the other hand, Campylobacter species, Escherichia coli, Chlamydia psittaci, Salmonella species, were found as main causal agent for the bacterial diseases occurring in pigeon and all of these pathogens have a dreadful effect on public health concern. Going more deeper, pigeons are the potential carrier for zoonotic pathogens, including Campylobacter species and Salmonella species that are mainly associated with severe acute gastroenteritis, Coxiella burnetii, the causal agent of Q fever and Chlamydia psittaci is responsible for respiratory tract infection in humans (Gabriele-Rivet et al., 2016; Weygaerde et al., 2018). In term of parasitic pathogens, Toxoplasma gondii was found more prevalent; whereas, single study reported for Enterocytozoon bieneus, Haemoproteus columbae, and Neospora caninum. Previous study revealed that Toxoplasma gondii is one of the most serious coccidian parasites, which infect human because of consuming raw and poorly cooked pigeon meat with Toxoplasma oocysts. Consequently, these birds may represent a public health problem for humans (Ibrahim et al., 2018). However, our analysis has few limitations, such as the dearth of multiple studies from every continent of the world and the risk of missing some studies to include. Given the limitations, our findings may vary slightly from the actual prevalence rate. Thus, we recommended that more rigorous molecular research should be performed for the finding of accurate global prevalence rate.

5. Conclusion

The current meta-analysis analyzed 49 articles with a total of 18,589 samples and revealed that the global prevalence of pigeon-borne zoonotic pathogens was 17%; analyzing the continent-wise result of all zoonotic pathogens from pigeon, the highest prevalence rate was found in Asia 20%, followed by Europe 16% and Africa 16%, the difference rate may be due to poor hygiene practices in developing countries in Asia rather than developed European countries. Besides, our result showed that the prevalence rate of viral pathogens is higher than bacterial and protozoal pathogens. This could be due to the new geographic areas being swiftly filled by rising human populations; as a result, people are more likely to live in close proximity to wild and pet birds, including pigeons. Therefore as a result, understanding the global epidemiological prevalence for intervention against these zoonoses is crucial for global public health. Moreover, raising public awareness about disease reporting to their local veterinary practitioners, as well as adopting prevention, control, and biosecurity techniques, can significantly reduce pigeon mortality.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Md. Mukthar Mia and Mahamudul Hasan: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper; M. Rashed Hasnath: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary content related to this article has been published online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09732.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Department of Poultry Science of Veterinary, Animal and Biomedical Sciences (Sylhet Agricultural University) for providing the support.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Akbarmehr J. Isolation of Salmonella spp. from poultry (ostrich, pigeon, and chicken) and detection of their hilA gene by PCR method. Afr. J. Microbiol Res. 2010;4:2678–2681. [Google Scholar]

- Al-abodi H.R.J. Vol. 16. 2017. pp. 136–141. (Serological and Molecular Detection of Toxoplasma gondii in Columba livia hunting pigeons of Al-Qadisiyah Province). [Google Scholar]

- Altamimi M.K.A. High prevalence of cryptosporidium meleagridis in domestic pigeons (Columba livia domestica) raises a prospect of zoonotic transmission in babylon province, Iraq. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 2020;44:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami S., Boroomand Z., Alborzi A.R., Namavari M., Mousavi S.B. A molecular and serological study of Neospora caninum infection in pigeons from southwest Iran. Vet. Arh. 2016;86:815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Ballmann M.Z., Harrach B. Detection and partial genetic characterisation of novel avi- and siadenoviruses in racing and fancy pigeons (Columba livia domestica) Acta Vet. Hung. 2016;64:514–528. doi: 10.1556/004.2016.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L.V., Higgins J.P.T., Rothstein H.R. John Wiley & Sons; 2021. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Bupasha Z.B., Begum R., Karmakar S., Akter R., Ahad A. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella spp. isolated from apparently healthy pigeons in a live bird market in Chattogram, Bangladesh. World's Vet. J. (WVJ) 2020;10:508–513. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Terriza D., Guerra R., Lecollinet S., Cerdà-Cuéllar M., Cabezón O., Almer∖’∖ia S., Garc∖’∖ia-Bocanegra I. Epidemiological survey of zoonotic pathogens in feral pigeons (Columba livia var. domestica) and sympatric zoo species in Southern Spain. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015;43:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong W., Huang S.Y., Zhang X.Y., Zhou D.H., Xu M.J., Zhao Q. Seroprevalence of Chlamydia psittaci infection in market-sold adult chickens , ducks and pigeons in north-western China Seroprevalence of Chlamydia psittaci infection in market-sold adult chickens , ducks and pigeons in north-western China. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;62:1211–1214. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.059287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong W., Huang S.Y., Zhou D.H., Xu M.J., Wu S.M., Yan C., Zhao Q., Song H.Q., Zhu X.Q. First report of Toxoplasma gondii infection in market-sold adult chickens, ducks and pigeons in northwest China. Parasites Vectors. 2012;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lima V.Y., Langoni H., da Silva A.V., Pezerico S.B., de Castro A.P.B., da Silva R.C., Araújo J.P. Chlamydophila psittaci and Toxoplasma gondii infection in pigeons (Columba livia) from São Paulo State, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;175:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey R.K., Khatun M.M., Islam M.A., Hosain M.S. Prevalence of multidrug resistant Escherichia coli in pigeon in mymensingh, Bangladesh. Microb Health. 2013;2:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dickx V., Beeckman D.S.A., Dossche L., Tavernier P., Vanrompay D. Chlamydophila psittaci in homing and feral pigeons and zoonotic transmission. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010;59:1348–1353. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.023499-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolz G., Angelova L., Tien C., Fonseca L., Bonilla M.C., Rica C. Chlamydia psittaci genotype B in a pigeon (Columba livia) inhabiting a public place in San José , Costa Rica. Open Vet. J. 2013;3:135–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doosti A., Ahmadi R., Mohammadalipour Z., Zohoor A., Collection A.B.S. International Conference on Biological, Civil and Environmental Engineering. 2014. Detection of Haemoproteus columbae in Iranian pigeons using PCR; pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dudzic A., Urban-Chmiel R., Stępień-Pyśniak D., Dec M., Puchalski A., Wernicki A. Isolation, identification and antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter strains isolated from domestic and free-living pigeons. Br. Poultry Sci. 2016;57:172–178. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2016.1148262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebani V.V., Bertelloni F., Mani P. Molecular survey on zoonotic tick-borne bacteria and chlamydiae in feral pigeons (Columba livia domestica) Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016;9:324–327. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elina K.C., Ahad A., Palash N.A., Anower A.M. Sero investigation of Newcastle disease virus in pigeons at chittagong metropolitan area, Bangladesh. Biomed. Lett. 2017;3:94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Esameili H., Khanjari A., Gholami F. Detection and characterization of Escherichia coli O157: H7 from feral pigeon in Qom province, Iran. Asian Pacific J. Trop. Dis. 2015;5:116–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele-Rivet V., Fairbrother J.-H., Tremblay D., Harel J., Côté N., Arsenault J. Prevalence and risk factors for Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., Coxiella burnetii, and Newcastle disease virus in feral pigeons (Columba livia) in public areas of Montreal, Canada. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2016;80:81–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo A., Russo T.P., Schettini R., Mallardo K., Calabria M., Menna L.F., Raia P., Pagnini U., Caputo V., Fioretti A., Dipineto L. Occurrence of enteropathogenic bacteria in Urban pigeons (columba livia) in Italy. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:251–255. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenfeind I., Vanrompay D., Haag-Wackernagel D. Prevalence of Chlamydia psittaci in the feral pigeon population of Basel, Switzerland. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012;61:261–265. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.034025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbanpoor M., Bakhtiari N., Mayahi M., Moridveisi H. Detection of Chlamydophila psittaci from pigeons by polymerase chain reaction in Ahvaz. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2015;7:18–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golestani N., Khoshkhoo P.H., Hosseini H., Azad G.A. Detection and identification of Chlamydia spp. from pigeons in Iran by nested PCR and sequencing. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2020;12:331. doi: 10.18502/ijm.v12i4.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Acuña D., Silva G.,F., Moreno S.,L., Cerda L.,F., Donoso E.,S., Cabello C.,J., López M.,J. Detección de algunos agentes zoonóticos en la paloma doméstica (Columba livia) en la ciudad de Chillán, Chile. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2007;24:199–203. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182007000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronesová P., Mižáková A., Betáková T. Determination of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtypes of avian influenza A viruses in urban pigeons by a new nested RT-PCR. Acta Virol. 2009;54:213–216. doi: 10.4149/av_2009_03_213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag-Wackernagel D., Bircher A.J. Ectoparasites from feral pigeons affecting humans. Dermatology. 2010;220:82–92. doi: 10.1159/000266039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helen Owoya A., Peter Friday O., Victor I. Survey for Newcastle disease virus antibodies in local chickens, ducks and pigeons in makurdi, Nigeria. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020;8:55. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim A.B., Wada Y., Kamardeen S. Seroprevalence of Newcastle disease virus in slaughtered pigeons from selected markets in zaria, kaduna state Nigeria. Res. Squre. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim H.M., Osman G.Y., Mohamed A.H., Al-selwi A.G.M., Nishikawa Y., Abdel-gha F. Toxoplasma gondii : prevalence of natural infection in pigeons and ducks from middle and upper Egypt using serological , histopathological , and immunohistochemical diagnostic methods. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports. 2018;13:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahantigh M., Nili H. Drug resistance of Salmonella spp. isolated from pigeon eggs. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2010;19:437–439. [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen C.M., Kofstad T., Larsen I.L., Løvland A., Handeland K., Follestad A., Lillehaug A. Molecular identification and characterization of novel coronaviruses infecting graylag geese (Anser anser), feral pigeons (Columbia livia) and mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:1597–1607. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80927-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorek-Łukowska E., Sowińska P., Franaszek A., Dziewulska D., Małaczewska J., Stenzel T. Can domestic pigeon be a potential carrier of zoonotic Salmonella? Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021;68:2321–2333. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim S.J.I., Islam M., Sikder T., Rubaya R., Halder J., Alam J. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. isolated from pigeons. Vet. World. 2020;13:2156–2165. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.2156-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koompapong K., Mori H., Thammasonthijarern N., Prasertbun R., Pintong A., Popruk S., Rojekittikhun W., Chaisiri K., Sukthana Y., Mahittikorn A. Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp . in seagulls , pigeons , dogs , and cats in Thailand. Parasite. 2014;21:1–7. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuralayanapalya S.P., Patil S.S., Hamsapriya S., Shinduja R., Roy P., Amachawadi R.G. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing bacteria from animal origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis report from India. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahzounieh M., Moloudizargari M., Ghasemi M., Abadi S., Khoei H.H. Prevalence rate and phylogenetic analysis of Chlamydia psittaci in pigeon and house sparrow specimens and the potential human infection risk in chahrmahal-va-bakhtiari, Iran. Arch. Clin. Infect Dis. 2020;15 [Google Scholar]

- Mattmann P., Marti H., Borel N., Jelocnik M., Albini S., Vogler B.R. Chlamydiaceae in wild, feral and domestic pigeons in Switzerland and insight into population dynamics by Chlamydia psittaci multilocus sequence typing. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi a., Masoudian M., Nemati Y., Seifi S. Serological and RT-PCR assays for detection of avian influenza of domestic pigeons in Kavar area (Fars province, Iran) Bulg. J. Vet. Med. 2010;13:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- O1E, W.O. for A.H. Avian Influenza [WWW Document] 2021. https://www.oie.int/en/disease/avian-influenza/ URL.

- Parmentier S.L., Maier-Sam K., Failing K., Gruber A.D., Lierz M. High prevalence of Sarcocystis calchasi in racing pigeon flocks in Germany. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S.S., Shinduja R., Suresh K.P., Phukan S., Kumar S., Sengupta P.P., Amachawadi R.G., Raut A., Roy P., Syed A., others A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of infectious diseases of Duck: a world perspective. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021;28:5131. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PCRC - P. contro resource center . 2021. Pigeons - everythings there there is to know about pigeons [WWW Document]https://www.pigeoncontrolresourcecentre.org/html/about-pigeons.html URL. [Google Scholar]

- Pekmezci D., Yetismis G., Colak Z.N., Duzlu O., Ozkilic G.N., Inci A., Pekmezci G.Z., Yildirim A. First report and molecular prevalence of potential zoonotic Enterocytozoon bieneusi in Turkish tumbler pigeons (Columba livia domestica) Med. Mycol. 2021;59:864–868. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myab013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sancho M., Garcia-Seco T., Porrero C., Garcia N., Gomez-Barrero S., Cámara J.M., Dominguez L., Álvarez J. A ten-year-surveillance program of zoonotic pathogens in feral pigeons in the City of Madrid (2005--2014): the importance of a systematic pest control. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020;128:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radimersky T., Frolkova P., Janoszowska D., Dolejska M., Svec P., Roubalova E., Cikova P., Cizek A., Literak I. Antibiotic resistance in faecal bacteria (Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp.) in feral pigeons. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;109:1687–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose E., Nagel P., Haag-Wackernagel D. Spatio-temporal use of the urban habitat by feral pigeons (Columba livia) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2006;60:242–254. [Google Scholar]

- Saifullah K., Mamun M., Rubayet R., Nazir K.H.M.N.H., Zesmin K. Molecular detection of Salmonella spp . isolated from apparently healthy pigeon in Mymensingh , Bangladesh and their antibiotic resistance pattern. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2016;7710:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Salant H., Landau D.Y., Baneth G. A cross-sectional survey of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in Israeli pigeons. Vet. Parasitol. 2009;165:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva V.L., Nicoli J.R., Nascimento T.C., Diniz C.G. Diarrheagenic escherichia coli strains recovered from urban pigeons (columba livia) in Brazil and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Curr. Microbiol. 2009;59:302–308. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel T., Pestka D., Choszcz D. The prevalence and genetic characterization of Chlamydia psittaci from domestic and feral pigeons in Poland and the correlation between infection rate and incidence of pigeon circovirus. Poultry Sci. 2014;93:3009–3016. doi: 10.3382/ps.2014-04219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sürsal N., Atan P., Gökpinar S., Duru Ö., Çakmak A., Yildiz K. Kirikkale yoresi’nde yetistirilen taklaci guvercinlerde (Columba livia domestica) Haemoproteus spp.’nin yayginligi/prevalence of Haemoproteus spp. in tumbler pigeons (Columba livia domestica) in kirikkale province, Turkey. Turkish J. Parasitol. 2017;41:71–76. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2017.5121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C., Miyazawa T., Watarai M., Ishiguro N. Bacteriological survey of feces from feral pigeons in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005;67:951–953. doi: 10.1292/jvms.67.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H.J., Lee C.Y. Serological survey of racing pigeons for selected pathogens in Taiwan. Acta Vet. Hung. 2006;54:179–189. doi: 10.1556/AVet.54.2006.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y.-J., Chung W.-C., Lei H.H., Wu Y. Prevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in pigeons (Columba livia) in Taiwan. J. Parasitol. 2006;92:871. doi: 10.1645/GE-716R2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vučemilo M., Vlahović K., Dovč A., MuŽinić J., Pavlak M., Jerčić J., Župančić Ž. Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella typhimurium, and avian Paramyxovirus type 1 (PMV-1) in pigeons from different regions in Croatia. Z. Jagdwiss. 2003;49:303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Weygaerde Y. Vande, Versteele C., Thijs E., De Spiegeleer A., Boelens J., Vanrompay D., Van Braeckel E., Vermaelen K. An unusual presentation of a case of human psittacosis. Respir. Med. Case Reports. 2018;23:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C., Yue C.L., Qiu S.B., Li H.L., Zhang H., Song H.Q., Huang S.Y., Zou F.C., Liao M., Zhu X.Q. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in domestic pigeons (Columba livia) in Guangdong Province of southern China. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;177:371–373. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.X., Qin S.Y., Li X., Ren W.X., Hou G., Zhao Q., Ni H.B. Seroprevalence and related factors of Toxoplasma gondii in pigeons intended for human consumption in northern China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019;19:302–305. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2018.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Q., Liu S., Zhang X., Jiang W., Wang K., Wang S., Peng C., Hou G., Li J., Yu X., Yuan L., Wang J., Li Y., Liu H., Chen J. Surveillance and taxonomic analysis of the coronavirus dominant in pigeons in China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020;67:1981–1990. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.