Abstract

Arnebiae Radix is a traditional medicine with pleiotropic properties that has been used for several 100 years. There are five species of Arnebia in China, and the two species Arnebia euchroma and Arnebia guttata are the source plants of Arnebiae Radix according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. Molecular markers that permit species identification and facilitate studies of the genetic diversity and divergence of the wild populations of these two source plants have not yet been developed. Here, we sequenced the chloroplast genomes of 56 samples of five Arnebia species using genome skimming methods. The Arnebia chloroplast genomes exhibited quadripartite structures with lengths from 149,539 and 152,040 bp. Three variable markers (rps16-trnQ, ndhF-rpl32, and ycf1b) were identified, and these markers exhibited more variable sites than universal chloroplast markers. The phylogenetic relationships among the five Arnebia species were completely resolved using the whole chloroplast genome sequences. Arnebia arose during the Oligocene and diversified in the middle Miocene; this coincided with two geological events during the late Oligocene and early Miocene: warming and the progressive uplift of Tianshan and the Himalayas. Our analyses revealed that A. euchroma and A. guttata have high levels of genetic diversity and comprise two and three subclades, respectively. The two clades of A. euchroma exhibited significant genetic differences and diverged at 10.18 Ma in the middle Miocene. Three clades of A. guttata diverged in the Pleistocene. The results provided new insight into evolutionary history of Arnebia species and promoted the conservation and exploitation of A. euchroma and A. guttata.

Keywords: Arnebiae Radix, Arnebia euchroma, Arnebia guttata, chloroplast genome, genetic diversity, phylogeography, phylogenomics

Introduction

Arnebiae Radix is a traditional Persian, Unani, Ayurvedic, and Chinese medicine with pleiotropic properties that has been used for several 100 years (Zhu, 1982; Kumar et al., 2021). Arnebiae Radix is an ingredient in 122 Chinese patent medicines and 195 Chinese medicine prescriptions. Shikonin, shikonofurans, and red naphthoquinones are the main effective chemical constituents, and they have been widely used for the treatment of infections, inflammation, and bleeding for their anti-inflammatory, anti-fungal, and anti-angiogenic activities (Gupta et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2021). Shikonin and its derivatives exhibit anti-cancer and anti-tumorigenic activities and have the potential to be used for the development of anti-tumor drugs (Feng et al., 2020; Liao et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2021). Arnebiae Radix has also been used in the printing, dyeing, and cosmetics industries (Ma et al., 2021). Although Arnebiae Radix is widely used for its varied medicinal effects, the evolutionary history of its source plants remains unclear.

Arnebiae Radix is the dried root of Arnebia euchroma (Royle ex Benth.) I. M. Johnst. and Arnebia guttata Bunge according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 version). Arnebia Forsskål is a genus in the family Boraginaceae and the tribe Lithospermeae. Arnebia comprises ca. 25 species and are distributed from North Africa to Central Asia and the Himalayas (Johnston, 1954). Only six Arnebia species to date have been reported from China (Zhu, 1982), including A. euchroma, A. guttata, A. decumbens (Ventenat) Cosson & Kralik, A. tschimganica (B. Fedtschenko) G. L. Chu, A. szechenyi Kanitz, and A. fimbriata Maximowicz. A. guttata (Inner Mongolia Arnebiae Radix) mainly occurs in Xizang, Xinjiang, western Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia in China. A. euchroma, commonly known as Xinjiang Arnebiae Radix, is an endangered herb (Kala, 2000; Gupta et al., 2014) that grows naturally on the slopes and dry patches in cold desert temperate zones of the western Himalayas (Xinjiang, western Xizang) (Lal et al., 2020). A. szechenyi inhabits sunny rocky slopes and sand dune edges; most populations of this species occur in areas surrounding the Tengger Desert in Northwest China (Fu et al., 2021). A. decumbens is an annual plant, and its native range extends from North Africa to Mongolia, including the Arabian Peninsula; it is also native to the Canary Islands. In China, its range is restricted to northern Xinjiang. A. fimbriata has a densely gray–white hirsute and is distributed in western Gansu, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Mongolia. A. tschimganica is an endangered herb in China (Qin et al., 2017). Recent studies have shown that this species belongs to the monotypic Ulugbekia [Ulugbekia tschimganica (B. Fedtsch.) Zakirov] (Weigend et al., 2009).

Owing to its various medicinal properties, Arnebia species have been overexploited, and the populations of some species have declined so much. There are two major outstanding problems regarding the exploitation and conservation of Arnebiae Radix and its source plants that need to be addressed. First, the sources of the medicinal materials of Arnebiae Radix in the market are complex according to one field study (Liu et al., 2020). Identification of source species is difficult based on morphological features; there is thus an urgent need to develop more efficient methods for species identification, such as DNA barcoding (Liu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021). Second, a sound understanding of patterns of genetic diversity and genetic divergence among wild plant populations is important for plant seeding and the conservation of threatened species (Funk et al., 2012). However, few studies have evaluated the population genetics of the source plants of Arnebiae Radix. Improved genetic markers need to be developed to facilitate the identification of the source species of Arnebiae Radix and clarify the population genetics of A. euchroma and A. guttata.

Chloroplasts are key plant organelles that are involved in photosynthesis and important biological processes, such as fatty acid and amino acid synthesis (Sugiura, 1992). The chloroplast genome of higher plants is a double-stranded and circular DNA molecule with a typical quadripartite structure (Dong et al., 2013, 2021a; Villanueva-Corrales et al., 2021), including a pair of inverted repeats (IRs) as well as a large single copy (LSC) and a small single copy (SSC) region. The chloroplast genome encodes approximately 80 protein-coding, 30 transfer RNA (tRNA), and four ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and the structure of the chloroplast genome, including the gene content and gene order, is conserved. An increasing number of chloroplast genomes are being sequenced due to the development of sequencing technology and genome assembly methods.

The nucleotide substitution rate of the chloroplast genome is moderate compared with that of the nuclear genome; it is also uniparentally inherited and exhibits low rates of recombination (Schwarz et al., 2017; Dong et al., 2020). Chloroplast genome sequences are thus effective for inferring phylogenetic relationships at various levels of divergence (Dong et al., 2018, 2022b), characterizing population structure (Qiao et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2021), identifying species (Ślipiko et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2021b), and elucidating patterns of genome evolution and molecular evolution (Dong et al., 2020). The chloroplast genomes of Arnebia have been compared with those of Lithospermum (Park et al., 2020); the full chloroplast genome sequences of A. guttata and A. euchroma have been published, and molecular markers have been developed at the genus level through comparative analysis. However, interspecific and intraspecific variation among Arnebia species has not yet been clarified. Multiple samples of species and genotypes would aid the development of markers for the identification of Arnebiae Radix species as well as for assessments of the population structure of A. euchroma and A. guttata.

Here, the chloroplast genomes of 56 Arnebiae Radix samples and its allies (including five Arnebia species) were sequenced and assembled using genome skimming methods. Specifically, we aimed to (i) elucidate variation in the chloroplast genome among Arnebia species in China, (ii) evaluate the divergence times among Arnebia species, (iii) identify markers that could be used to discriminate between different Arnebia species, and (iv) evaluate the genetic structure of and genetic divergence between A. euchroma and A. guttata. The chloroplast genome resources presented in this study will aid the conservation and exploitation of Arnebia species.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Fifty-six samples covering five Arnebia species were included in this study. A total of 50 samples were collected from field in China. DNA of four samples from Russia, and two from Mongolia were acquired from the DNA bank of China in Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The samples included seven genotypes of A. decumbens, 15 genotypes of A. euchroma, six genotypes of A. fimbriata, 17 genotypes of A. guttata, and 11 genotypes of A. szechenyi. Samples were derived from various localities in Asia and were representative of the geographical distributions of the five Arnebia species. Sample information is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Genome Sequencing and Chloroplast Genome Assembly

Total DNA was extracted using the modified CTAB method (Li et al., 2013). DNA quality was measured using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, United States). A total of 500 ng of DNA was used for sequencing library preparation. Total DNA was sheared to 350-bp fragments using an ultrasonicator. Illumina paired-end DNA library construction and paired-end whole-genome shotgun resequencing (150 bp) on an Illumina HiSeq X-ten platform at Novogene (Tianjin, China) were performed; each sample yielded approximately 5 Gb of data.

Quality control of the raw data was conducted using Trimmomatic 0.36 (Bolger et al., 2014) with the following parameters: LEADING, 20; TRAILING, 20; SLIDING WINDOW, 4:15; MIN LEN, 36; and AVG QUAL, 20. GetOrganelle (Jin et al., 2020) with k-mer lengths of 85, 95, and 105 was used to assemble the whole chloroplast genomes. If GetOrganelle was unable to successfully assemble the whole chloroplast genome, we followed the methods of Dong et al. (2022a) to assemble the chloroplast genome sequences. Genomes were annotated using Plann (Huang and Cronk, 2015), and the published genome of A. guttata (GenBank Accession number: MT975391) was used as the reference sequence. Annotated whole chloroplast genome sequences were submitted to GenBank. The Arnebia chloroplast genomes maps were depicted using Chloroplot (Zheng et al., 2020).

Development of Molecular Markers

All the chloroplast genome sequences were aligned using MAFFT 7 (Katoh and Standley, 2013) and adjusted manually using Se-Al 2.0 (Rambaut, 1996); for example, alignment errors associated with polymeric repeat structures and small inversions were corrected to avoid overestimation of sequence divergence. mVISTA and nucleotide diversity (π) were used to analyze interspecific variation in Arnebia chloroplast genomes (Frazer et al., 2004). Mutational hotspots were identified by sliding window methods; the window size was set to 800 bp, and the step size was set to 100 bp.

Nucleotide diversity, variable, and parsimony-informative sites were used to assess marker variability for hypervariable markers (mutational hotspot regions). The three universal chloroplast DNA markers, rbcL, matK, and trnH-psbA, were used in this analysis to compare variation between hypervariable markers and universal chloroplast DNA markers. The number of variable and parsimony-informative sites and nucleotide diversity (π) were calculated using MEGA 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016) and DnaSP v6 (Rozas et al., 2017).

Phylogenetic Analyses

We used all the coding genes to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among Arnebia and other Lithospermeae species at the species level. The dataset included 12 Arnebia samples and samples from eight other Boraginaceae species. Coding genes were extracted using Geneious Prime v2020.0.5 based on annotation of the chloroplast genomes. Nucleotide and amnio acid sequences were used for phylogenetic analyses. The whole chloroplast genome dataset of all Arnebia samples was used to infer the phylogenetic relationships among all genotypes.

Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) were used to infer phylogenetic relationships. ML analyses were run using RAxML-NG (Kozlov et al., 2019) with 500 bootstrap replicates. ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017) was used to select the best-fit model of nucleotide substitution with the Bayesian information criterion. The BI tree was generated in MrBayes v3.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012). The BI analysis was run with two independent chains and priors for 20 million generations, with sampling every 1,000 generations. The stationary phase was examined using Tracer 1.6 (Rambaut et al., 2014), and the first 25% of the sampled trees was discarded. The remaining trees were used to generate a majority-rule consensus tree to estimate posterior probabilities.

Time Calibration of the Phylogeny

The chloroplast gene data were used to estimate the divergence times among Arnebia species. Two priors from the findings of (Chacón et al., 2019) were used for these analyses. The crown age of Lithospermeae was constrained to 42.5 Mya [95% highest posterior density (HPD): 35.3–51.5 Mya]. The crown age of Onosma and Lithospermum was 32.1 Mya. The two priors were placed under a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 1.

We used the whole chloroplast genome data of 56 genotypes of the five Arnebia species to infer divergence times at the intraspecific level. Three priors from the above results were used for this analysis: (i) the crown age of Arnebia (the root of the tree); (ii) the crown age of A. guttata and A. decumbens; and (3) the crown age of A. euchroma and A. szechenyi/A. fimbriata. All three priors were placed under a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 1.

The divergence time analyses were performed in BEAST 2 (Bouckaert et al., 2014). The prior tree Yule model and GTR model were selected with the uncorrelated lognormal distribution relaxed molecular clock model, and the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) tool was run for 500,000,000 generations with sampling every 50,000 generations. Tracer 1.6 (Rambaut et al., 2014) was used to evaluate convergence and to ensure a sufficient and effective sample size for all parameters surpassing 200. A maximum credibility tree was generated with mean heights in TreeAnnotator, with the first 10% of the trees discarded as burn-in.

Genetic Diversity and Population Differentiation of Arnebia euchroma and Arnebia guttata

Number of variable sites, nucleotide diversity (π), and number of haplotypes were calculated using MEGA 7.0 and DnaSP v6 within the five species to characterize intraspecific variation in genetic diversity. Filtered intraspecific SNPs were used to analyze population structure with an admixture model-based clustering method implemented in STRUCTURE v. 2.3.4 (Falush et al., 2007). Allele frequencies were assumed to be correlated among populations (K = 1 to K = 10). The most likely number of clusters was determined based on both LnP(D) and Δk. Principal component analysis (PCA) was also used to assess genetic structure. PCA was conducted using Plink (Purcell et al., 2007), and graphs were built using the ggbiplot package in R.

Results

Structure, Gene Content, and Sequences in Five Arnebia Species Chloroplast Genomes

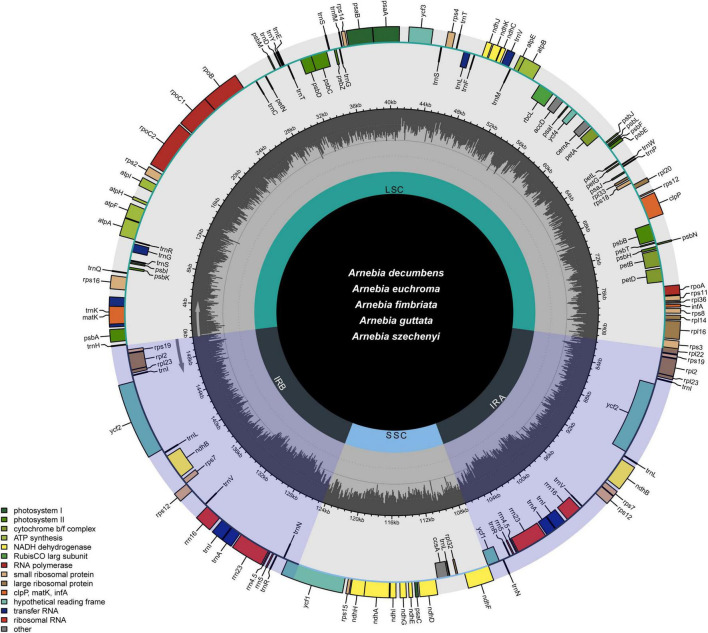

The whole chloroplast genomes of the five Arnebia species had the quadripartite structure typical of most angiosperm species (Figure 1). The length of the 56 chloroplast genomes ranged between 149,539 and 152,040 bp (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The LSC (between 80,462 and 82,946 bp) and SSC (between 17,143 and 17,336 bp) were separated by two IR regions (IRa and IRb, between 25,753 and 26,053 bp). The overall GC content was approximately 37.5–37.8%, and the GC content was slightly higher in the IR (43.0%) regions than in the LSC (35.6%) and SSC (31.3%) regions. The Arnebia chloroplast genome encoded 112 unique genes, including 78 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes, and four rRNA genes. Eighteen genes had introns; 16 genes had a single intron, and two genes (ycf3 and clpP) had two introns. There were three intron-containing genes (ndhB, trnI-GAU, and trnA-UGC) in the IR regions. The matK gene was located in trnK-UUU, which is the largest intron in the chloroplast genome, and the rps12 gene was trans-spliced, with two copies of the 3′ end in the IR region and the 5′ end in the LSC region. The IR/SC boundaries slightly differed among the five Arnebia species. For example, the trnH gene was located in the LSC region, 12 to 42 bp from the IRa/LSC boundary.

FIGURE 1.

Gene map of the Arnebia chloroplast genome. Genes are colored according to functional categories.

TABLE 1.

Chloroplast genome features of the five Arnebia species.

| Species | Nucleotide length (bp) |

GC content (%) | Number of genes |

||||||

| LSC | IR | SSC | Total | Protein | tRNA | rRNA | Total | ||

| Arnebia decumbens | 80,462–80,826 | 25,943–25,945 | 17,188–17,203 | 149,539–149,919 | 37.8 | 78 | 30 | 4 | 112 |

| Arnebia euchroma | 81,086–81,708 | 25,918–25,968 | 17,256–17,336 | 150,224–150,900 | 37.6 | 78 | 30 | 4 | 112 |

| Arnebia fimbriata | 82,846–82,946 | 25,896–25,899 | 17,289–17,298 | 151,927–152,040 | 37.5 | 78 | 30 | 4 | 112 |

| Arnebia guttata | 80,737–81,265 | 25,967–26,053 | 17,143–17,213 | 149,840–150,410 | 37.7 | 78 | 30 | 4 | 112 |

| Arnebia szechenyi | 82,064–82,569 | 25,753–25,940 | 17,156–17,302 | 150,867–151,701 | 37.6-37.7 | 78 | 30 | 4 | 112 |

Genome Variation and Molecular Marker Identification

The mVISTA results revealed high synteny among the chloroplast genomes of the five Arnebia species, which indicates that the chloroplast genome is highly conserved in this genus (Supplementary Figure 1). The 65 whole chloroplast genomes had an aligned length of 157,292 bp (Table 2), including 4,921 variable sites (3.13%) and 3,996 parsimony-informative sites (2.54%). The overall nucleotide diversity (π) of the chloroplast genome was 0.00634. The nucleotide diversity was lowest for the IR region (0.00177) and highest for the SSC region (0.01234). The SSC region also had the highest proportion of variable sites and parsimony-informative sites. These results indicate that the SSC region had the highest mutation rate and sequence divergence and that the IR region was more conserved compared with other regions (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Analyses of the variable sites in chloroplast genomes of Arnebia.

| Regions | Aligned length (bp) | Variable sites |

Information sites |

Nucleotide diversity | Number of haplotypes | ||

| Numbers | % | Numbers | % | ||||

| LSC | 87,252 | 3,518 | 4.03 | 2,861 | 3.28 | 0.00843 | 49 |

| SSC | 17,664 | 964 | 5.46 | 791 | 4.48 | 0.01234 | 48 |

| IR | 26,179 | 214 | 0.82 | 168 | 0.64 | 0.00177 | 36 |

| Whole chloroplast genome | 157,202 | 4,921 | 3.13 | 3,996 | 2.54 | 0.00654 | 49 |

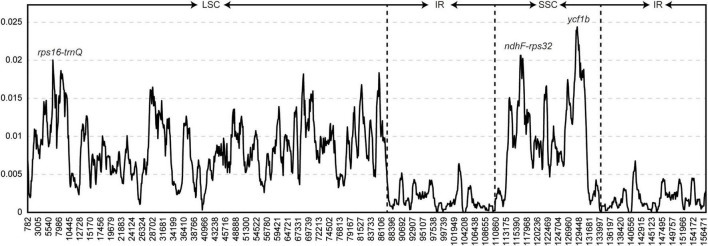

The sliding window method was used to identify mutational hotspots in the whole chloroplast genome using a window size of 800 bp (Figure 2). The π values ranged from 0 to 0.02439. Nucleotide diversity was lowest in the IR region. Three peaks were identified in the 65 whole chloroplast genomes, with π values >0.02. The three markers contained the two intergenic regions rps16-trnQ and ndhF-rpl32 and the coding region ycf1b. rps16-trnQ was located in the LSC region, and ndhF-rps32 and ycf1b were located in the SSC region.

FIGURE 2.

Hypervariable regions in the Arnebia chloroplast genome. Window length: 800 bp; step size: 100 bp. Three regions with the highest π values were marked. x-axis: position of the midpoint of a window; y-axis: nucleotide diversity of each window.

We compared the number of variable sites among the three hypervariable markers and the three universal DNA barcodes (rbcL, matK, and trnH-psbA). Marker information is shown in Table 3. The length of the three hypervariable markers was 971 bp (rps16-trnQ), 1,640 bp (ndhF-rpl32), and 1,843 bp (ycf1b). Ycf1b had the greatest number of variable sites (153 sites), followed by ndhF-rpl32 (125 sites) and rps16-trnQ (72 sites). The number of variable sites for rbcL, matK, and trnH-psbA was 67, 73, and 40, respectively. Ycf1b had the highest π value and showed more sequence divergence among the six markers, followed by trnH-psbA and rps16-trnQ. RbcL and matK were less variable according to the π values.

TABLE 3.

Three hypervariable regions and the universal markers of chloroplast genomes of Arnebia.

| Barcode | Number of sequences | Length (bp) | Variable sites |

Information sites |

Nucleotide diversity (π) | ||

| Numbers | % | Numbers | % | ||||

| rps16-trnQ | 56 | 971 | 72 | 7.42 | 60 | 6.18 | 0.02002 |

| ndhF-rpl32 | 56 | 1,640 | 125 | 7.62 | 107 | 6.52 | 0.01852 |

| ycf1b | 56 | 1,843 | 153 | 8.30 | 130 | 7.05 | 0.02087 |

| trnH-psbA | 56 | 472 | 67 | 14.19 | 54 | 11.44 | 0.02019 |

| matK | 56 | 1,536 | 73 | 4.75 | 57 | 3.71 | 0.00936 |

| rbcL | 56 | 1,434 | 40 | 2.79 | 34 | 2.37 | 0.00668 |

Plastid Phylogenomics of Arnebia

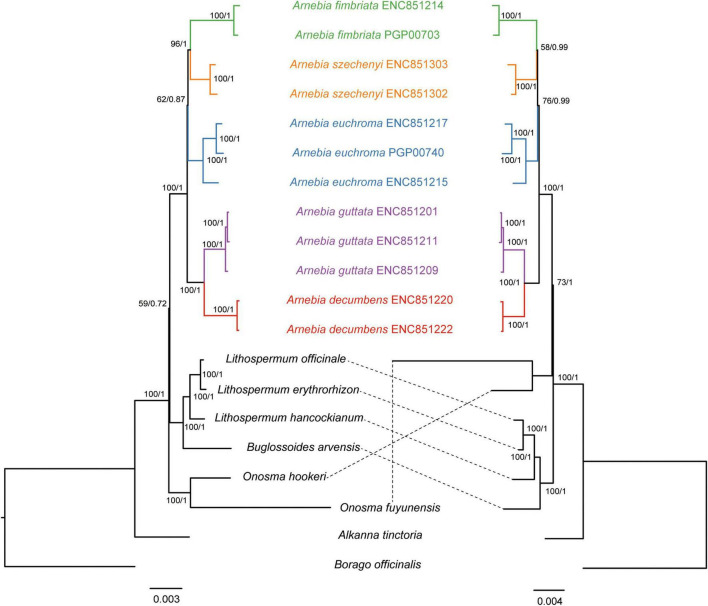

All 78 protein-coding genes of the chloroplast genome were used to infer the phylogenetic relationships among Arnebia species and their allies through BI and ML (Figure 3). The nucleotide data matrix contained 67,557 sites, including 4,712 variable sites and 1,675 parsimony-informative sites. The amino acid data matrix contained 22,519 sites, including 1,834 variable sites and 626 parsimony-informative sites.

FIGURE 3.

Phylogenetic trees of Lithospermeae based on all protein-coding genes. The nucleotide dataset (left) and amino acid dataset (right). Maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap support values/Bayesian posterior probabilities are shown at each node.

The topologies of the ML and BI tree were consistent, and most nodes had strong support values. Alkanna tinctoria was the first group to diverge from Lithospermeae. The nucleotide dataset indicated that Onosma was the second group to diverge from [name]; however, the sequence of divergence inferred from the amino acid dataset differed from that inferred by the nucleotide dataset. Both datasets indicated that Buglossoides was sister to Lithospermum and formed a clade. Arnebia, Buglossoides, and Lithospermum formed a monophyletic group with low support values (BS = 59/PP = 0.72) based on the nucleotide dataset; the amnio acid dataset indicated that Arnebia was sister to Onosma (BS = 73/PP = 1). The inferred phylogenetic relationships among the five Arnebia species predicted by both datasets were similar (BS = 100/PP = 1). A. decumbens and A. guttata formed a clade with strong support values. A. fimbriata and A. szechenyi formed a clade that was sister to A. euchroma with moderate support values (BS = 62/PP = 0.87 or BS = 62/PP = 0.99). All the samples for each species formed a monophyletic group with high support values based on the whole chloroplast genome sequences.

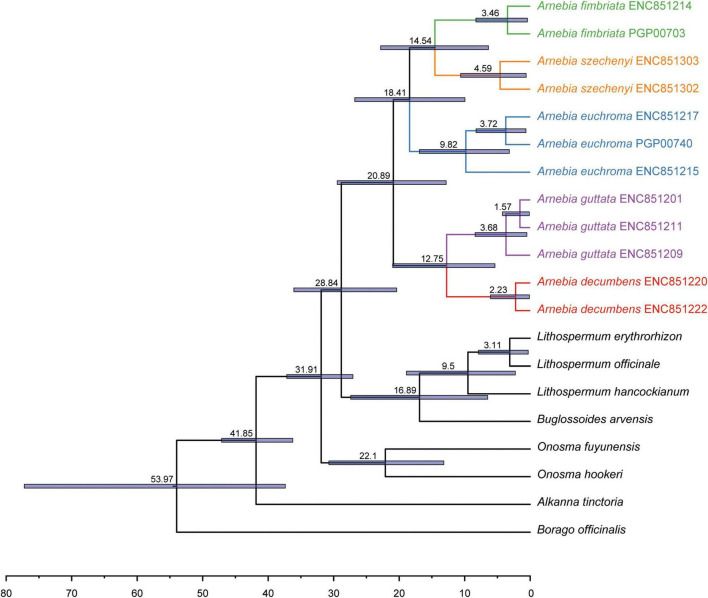

Divergence Time Estimation

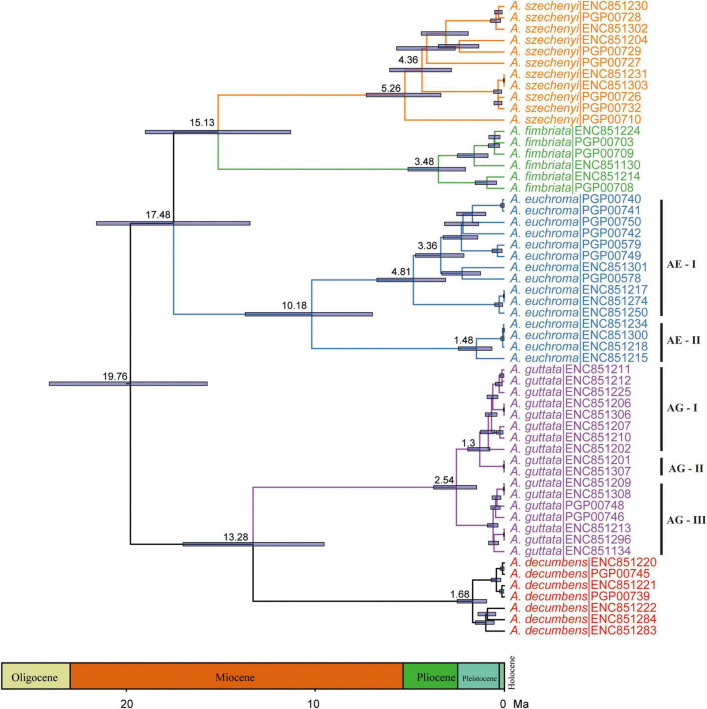

Divergence time estimates showed that the stem and crown nodes of Arnebia were 28.84 Ma (95% HPD: 20.05–35.69 Ma) in the middle Oligocene and 20.89 Ma (95% HPD: 12.82–29.46 Ma) in the early Miocene, respectively (Figure 4). The divergence time between A. guttata and A. decumbens was 12.75 Ma (95% HPD: 5.37–20.99 Ma) in the middle Miocene. The three species A. fimbriata, A. szechenyi, and A. euchroma diverged at 18.41 Ma, and the divergence time between A. szechenyi and A. euchroma was 14.54 Ma. The genotype-level divergence times were estimated using all samples (Figure 5). The crown ages of A. szechenyi, A. euchroma, A. fimbriata, A. guttata, and A. decumbens were 5.26, 3.48, 10.18, 2.54, and 1.68 Ma, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Divergence times of Lithospermeae obtained from BEAST analysis based on all coding protein-coding genes with two priors. The mean divergence time of the nodes is shown next to the nodes, and the blue bars correspond to the 95% highest posterior density (HPD).

FIGURE 5.

Divergence times of Arnebia obtained from BEAST analysis based on the 65 whole chloroplast genomes. The mean divergence time of the nodes is shown next to the nodes, and the blue bars correspond to the 95% HPD.

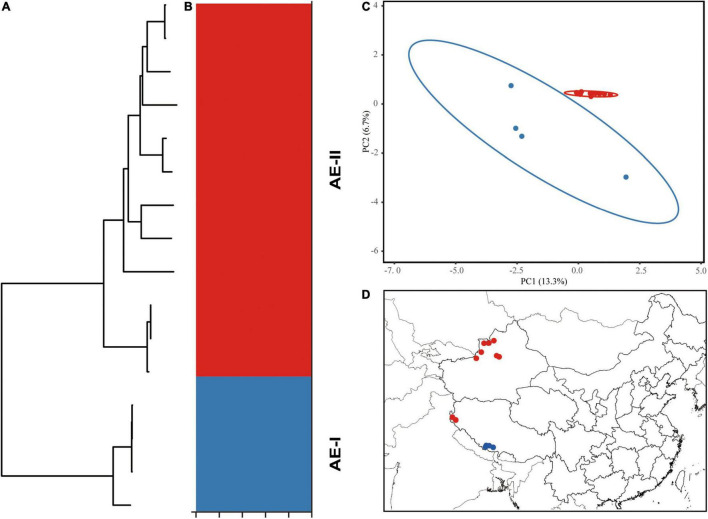

Intraspecific Diversity and Genetic Structure of Arnebia euchroma

The 15 aligned chloroplast genomes of A. euchroma were 152,175 bp in length. A total of 1,167 mutation sites were identified, including 339 singleton and 827 parsimony-informative sites (Table 4). We also identified 265 indels in the A. euchroma chloroplast genome. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using ML and BI and whole chloroplast genomes (Figure 6A). These samples were clearly divided into two clades (AE-I and AE-II). Population structure was analyzed using K values ranging from 1 to 10; the populations were clearly divided into two clades with K = 2 (Figure 6B). The PCA results revealed two major groups (Figure 6C). The AE-I clade included four samples located in southern Tibet (Jilong County and Zada County) (Figure 6D). The two clades exhibited significant genetic differences and diverged at 10.18 Ma in the middle Miocene (Figure 5).

TABLE 4.

Intraspecific chloroplast genome sequence divergence of five Arnebia species.

| Species | Number of samples | Alignment length (bp) | Number of variable sites |

Nucleotide polymorphism |

|||

| Polymorphic | Singleton | Parsimony informative | Nucleot ide diversity | Haplotypes | |||

| Arnebia decumbens | 7 | 150,133 | 157 | 86 | 70 | 0.00041 | 7 |

| Arnebia euchroma | 15 | 152,175 | 1,167 | 339 | 827 | 0.00241 | 14 |

| Arnebia fimbriata | 6 | 152,386 | 304 | 135 | 168 | 0.00089 | 6 |

| Arnebia guttata | 17 | 150,929 | 313 | 77 | 236 | 0.00058 | 14 |

| Arnebia szechenyi | 11 | 152,438 | 709 | 445 | 259 | 0.00133 | 10 |

FIGURE 6.

Intraspecific diversity and genetic structure of 15 Arnebia euchroma genotypes based on whole chloroplast genomes. (A) Phylogenetic tree; (B) population structure analysis with K = 2; (C) principal component analysis; (D) geographical distribution information.

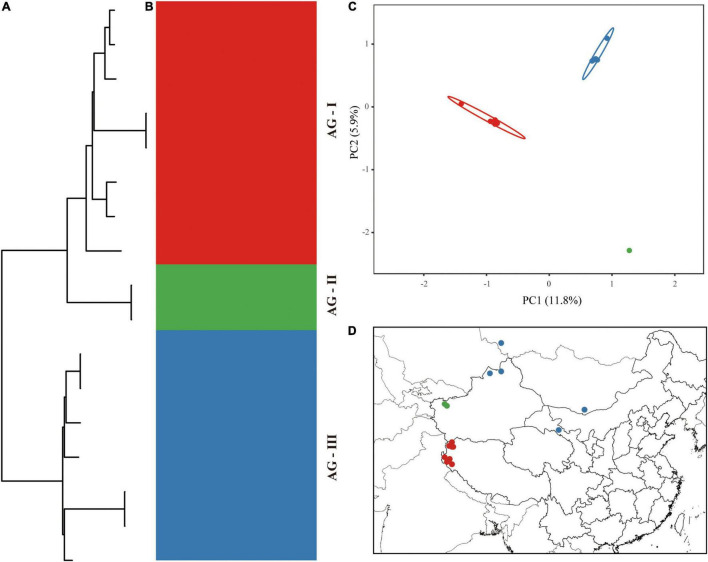

Intraspecific Diversity and Genetic Structure of Arnebia guttata

The aligned 17 chloroplast genomes of A. guttata were 150,929 bp in length. A total of 313 mutation sites were screened, including 77 singleton and 236 parsimony-informative sites. The nucleotide diversity and number of haplotypes were 0.00058 and 14 for the 17 A. guttata chloroplast genome sequences, respectively. The sequence divergence among the A. guttata chloroplast genome sequences was lower than that among the A. euchroma chloroplast genome sequences (Table 4). The samples were clearly divided into three clades (AG-I, AG-II, and AG-III) according to the phylogenetic relationships (Figure 7A), STRUCTURE analysis (Figure 7B), and PCA (Figure 7C). The AG-I clade contained eight samples from Mongolia, Russia, Gansu Province, and northwestern Xinjiang, China. The AG-II clade included two samples from Tacheng, Xinjiang. The AG-III clade contained seven samples from northwestern Tibet (Figure 7D). The divergence times among the three clades ranged from 1.2 to 2.54 Ma in the Pleistocene (Figure 5).

FIGURE 7.

Intraspecific diversity and genetic structure of 17 A. guttata genotypes based on whole chloroplast genomes. (A) Phylogenetic tree; (B) population structure analysis with K = 3; (C) principal component analysis; (D) geographical distribution information.

Discussion

Inter- and Intraspecific Variation in the Chloroplast Genomes of Arnebia Species

The aim of this study was to explore patterns of chloroplast genome divergence in Arnebia species in China. The chloroplast genomes of the five Arnebia species were conserved, as little variation was observed in their size, GC content, and gene order among species. The organization of Arnebia genomes was similar to that of other members of the family Boraginaceae and exhibited a typical quadripartite structure. The mVISTA results and DnaSP results revealed that the LSC and SSC regions were more variable than the IR regions, and the non-coding regions were more variable than the coding regions. Mutation events were not random but clustered into hotspots in the chloroplast genome (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). Mutational hotspot regions were more variable than universal chloroplast markers (rbcL, matK, and trnH-psbA) or commonly used markers, such as ndhF and trnL-F. Three variable regions (rps16-trnQ, ndhF-rpl32, and ycf1b) were identified in the Arnebia chloroplast genome. rps16-trnQ was located in the LSC region, and this marker has long been used for the reconstruction of plant phylogenies and species identification (Smedmark et al., 2008). The rps16-trnQ marker contains the rps16 intron and the intergenic spacer rps16-trnQ (Shaw et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2012). rps16-trnQ shows greater variation in the chloroplast genome. However, it contains a larger inversion in papilionoid species. The intergenic spacer ndhF-rpl32 is located in the SSC region. This marker was identified by Shaw et al. (2007) and Dong et al. (2012), and both of these studies suggested that this marker could be used to conduct phylogenetic studies at the species or subspecies level because of its higher level of variability compared with other chloroplast markers. The ycf1 gene is the second longest gene in the chloroplast genome, and this gene spans the IR and SSC regions. Two variable regions in this gene, ycf1a and ycf1b, have been identified (Dong et al., 2012, 2015). In the Arnebia chloroplast genome, ycf1b was the most variable marker (Figure 2 and Table 3). ycf1 has also been shown to vary substantially among different varieties (Magdy et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2021).

Chloroplast genome markers have long been used in plant population genetic studies, but these markers generally have few polymorphic sites. We identified many intraspecific mutations in Arnebia species (Table 4), and A. euchroma and A. szechenyi had a higher number of variable sites in the chloroplast genome. The polymorphic sites generate a sufficient number of haplotypes, and most of the sampled population exhibited private haplotypes. There were more variable sites in the chloroplast genomes of Arnebia species compared with other woody plants. Variation in the substitution rate among taxa has been examined by various studies (Smith and Donoghue, 2008; Amanda et al., 2017; Schwarz et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2021). Generation time variation is the generally accepted explanation for substitution rate variation; specifically, nucleotide substitution rates are thought to be negatively correlated with generation time (Smith and Donoghue, 2008; Amanda et al., 2017).

The genetic information contained in the chloroplast genome at the inter- and intraspecific levels can improve our understanding of plant evolution and population genetics. The rich genetic variation of Arnebia species can also enhance the breeding of herbal varieties.

Phylogenetic Relationships and Divergence Times Among Arnebia Species

Arnebia species are annual or perennial plants. Johnston (1954) suggested that the genus comprises two sections: Sect. Euarnebia, which includes one annual species A. tetrastigma Forsskål, and sect. Strobilia, which is further subdivided into three subgroups according to its life cycle (annual/perennial) and the presence of a pubescent annulus at the base of the corolla tube. Molecular data have indicated that Arnebia s.l. (including Macrotomia) is not monophyletic (Coppi et al., 2015); however, the molecular markers used in these studies do not provide sufficient resolution for resolving species-level relationships in this group (Weigend et al., 2009; Coppi et al., 2015; Chacón et al., 2019). In this study, we used whole chloroplast genomes to infer the phylogenetic relationships among Arnebia species in China, and the whole chloroplast genomes provided sufficient information for resolving phylogenetic relationships at the species and subspecies level. The chloroplast genome tree did not group species by life cycle, and this finding was inconsistent with the internal transcribed spacer tree, which indicates that Arnebia s.s. formed a monophyletic group subdivided into two lineages corresponding to the groups of annual and perennial species (Coppi et al., 2015).

We estimated the divergence time of Arnebia based on the chloroplast genome at the species and subspecies levels. Arnebia originated from the Oligocene and diversified in the middle Miocene (Figure 4; Chacón et al., 2019). Late Oligocene warming and the progressive uplift of Tianshan and the Himalayas in the early Miocene (Favre et al., 2015) might be the main factors underlying the origin and diversification of Arnebia.

Genetic Divergence of Arnebia euchroma and Arnebia guttata in China

Arnebia euchroma and A. guttata are the two source plants of Arnebiae Radix. Wild populations of these species have declined due to overharvesting, habitat destruction, and fragmentation (Samant et al., 1998; Qin et al., 2017). Both species are difficult to grow via conventional agricultural practices (Kumar et al., 2021), and this has resulted in the increased use of wild resources. Studies of genetic diversity are essential for plant seeding, agricultural practices, as well as the conservation of endangered species.

Our analyses based on the whole chloroplast genome revealed a considerably high level of genetic variation within A. euchroma and A. guttata (Table 4). Most of the samples had specific genotypes. A. euchroma was divided into two clades that showed significant genetic divergence (Figure 6). Divergence time estimation indicated that the two clades diverged the in late Miocene (10.18 Ma), and intraspecific divergence occurred earlier compared with other plants. We carefully examined the morphological characteristics of the populations from southern Xizang (Jilong County and Zada County) (AE-I clade), and none of them were misidentified. The AE-I clade might contain cryptic species, and more samples and field studies need to be performed in the future to explore this possibility. A. guttata was the source of Inner Mongolia Arnebiae Radix. Chinese populations comprised three subclades (Figure 7), which were consistent with the geographical distributions of this species. The divergence time of this species was estimated to be 2.54 Ma in the Pleistocene.

Several studies have shown that some herbaceous plants occurring in drylands show high levels of genetic variation (Meng and Zhang, 2011; Zhang et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2021). Ecological conditions in the drylands and the long evolutionary histories of desert plants are probably associated with the high levels of genetic variation (Meng and Zhang, 2011). The drylands and the mountains likely result in discrete patches of vegetation, which reduces gene flow and genetic similarity among populations (Maestre et al., 2012).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the GenBank, accession number ON529903-ON529958.

Author Contributions

WD, LG, and LH conceived and designed the work. JS, SW, RW, KL, PQ, and LS collected the samples. JS, EL, YW, SW, RW, KL, PQ, and LS performed the experiments and analyzed the data. WD, JS, and SW wrote the manuscript. LG and LH revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank the DNA Bank of China in Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing materials.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82173934), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (ZZXT201901), CACMS Innovation Fund (CI2021A03904) and Key Project at Central Government level: the ability establishment of sustainable use for valuable Chinese medicine resources (2060302).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.920826/full#supplementary-material

Comparison of the five Arnebia species chloroplast genomes using mVISTA.

References

- Amanda R., Li Z., van de Peer Y., Ingvarsson P. K. (2017). Contrasting rates of molecular evolution and patterns of selection among gymnosperms and flowering plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34 1363–1377. 10.1093/molbev/msx069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert R., Heled J., Kuhnert D., Vaughan T., Wu C. H., Xie D., et al. (2014). BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comp. Biol. 10:e1003537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón J., Luebert F., Selvi F., Cecchi L., Weigend M. (2019). Phylogeny and historical biogeography of Lithospermeae (Boraginaceae): Disentangling the possible causes of Miocene diversifications. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 141:106626. 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K., Weng M.-L., Ruhlman T. A., Jansen R. K. (2021). Extensive variation in nucleotide substitution rate and gene/intron loss in mitochondrial genomes of Pelargonium. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 155:106986. 10.1016/j.ympev.2020.106986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppi A., Cecchi L., Nocentini D., Selvi F. (2015). Arnebia purpurea: a new member of formerly monotypic genus Huynhia (Boraginaceae-Lithospermeae). Phytotaxa 204 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Li E., Liu Y., Xu C., Wang Y., Liu K., et al. (2022a). Phylogenomic approaches untangle early divergences and complex diversifications of the olive plant family. BMC Biol. 20:92. 10.1186/s12915-022-01297-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Liu J., Yu J., Wang L., Zhou S. (2012). Highly variable chloroplast markers for evaluating plant phylogeny at low taxonomic levels and for DNA barcoding. PLoS One 7:e35071. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Liu Y., Li E., Xu C., Sun J., Li W., et al. (2022b). Phylogenomics and biogeography of Catalpa (Bignoniaceae) reveal incomplete lineage sorting and three dispersal events. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 166:107330. 10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Liu Y., Xu C., Gao Y., Yuan Q., Suo Z., et al. (2021a). Chloroplast phylogenomic insights into the evolution of Distylium (Hamamelidaceae). BMC Genom. 22:293. 10.1186/s12864-021-07590-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Sun J., Liu Y., Xu C., Wang Y., Suo Z., et al. (2021b). Phylogenomic relationships and species identification of the olive genus Olea (Oleaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2021:802. 10.1111/jse.12802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Xu C., Cheng T., Lin K., Zhou S. (2013). Sequencing angiosperm plastid genomes made easy: a complete set of universal primers and a case study on the phylogeny of Saxifragales. Genome Biol. Evol. 5 989–997. 10.1093/gbe/evt063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Xu C., Li C., Sun J., Zuo Y., Shi S., et al. (2015). ycf1, the most promising plastid DNA barcode of land plants. Sci. Rep. 5:8348. 10.1038/srep08348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Xu C., Wen J., Zhou S. (2020). Evolutionary directions of single nucleotide substitutions and structural mutations in the chloroplast genomes of the family Calycanthaceae. BMC Evol. Biol. 20:96. 10.1186/s12862-020-01661-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Xu C., Wu P., Cheng T., Yu J., Zhou S., et al. (2018). Resolving the systematic positions of enigmatic taxa: manipulating the chloroplast genome data of Saxifragales. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 126 321–330. 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D., Stephens M., Pritchard J. K. (2007). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol. Ecol. Notes 7 574–578. 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01758.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre A., Päckert M., Pauls S. U., Jähnig S. C., Uhl D., Michalak I., et al. (2015). The role of the uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau for the evolution of Tibetan biotas. Biol. Rev. 90 236–253. 10.1111/brv.12107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Yu P., Zhou Q., Tian Z., Sun M., Li X., et al. (2020). An integrated data filtering and identification strategy for rapid profiling of chemical constituents, with Arnebiae Radix as an example. J. Chromatograph. 1629:461496. 10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer K. A., Pachter L., Poliakov A., Rubin E. M., Dubchak I. (2004). VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 W273–W279. 10.1093/nar/gkh458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M.-J., Wu H.-Y., Jia D.-R., Tian B. (2021). Evolutionary history of a desert perennial Arnebia szechenyi (Boraginaceae): Intraspecific divergence, regional expansion and asymmetric gene flow. Plant Divers. 43 462–471. 10.1016/j.pld.2021.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk W. C., Mckay J. K., Hohenlohe P. A., Allendorf F. W. (2012). Harnessing genomics for delineating conservation units. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27 489–496. 10.1016/j.tree.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K., Garg S., Singh J., Kumar M. (2014). Enhanced production of napthoquinone metabolite (shikonin) from cell suspension culture of Arnebia sp. and its up-scaling through bioreactor. 3 Biotech 4 263–273. 10.1007/s13205-013-0149-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. I., Cronk Q. C. B. (2015). Plann: A command-line application for annotating plastome sequences. Appl. Plant Sci. 3:1500026. 10.3732/apps.1500026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.-J., Yu W.-B., Yang J.-B., Song Y., Depamphilis C. W., Yi T.-S., et al. (2020). GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 21:241. 10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston I. M. (1954). Studies in the Boraginaceae XXVI. Further revaluations of the genera of the Lithospermeae. J. Arnold Arboretum 35 1–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kala C. P. (2000). Status and conservation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya. Biol. Conserv. 93 371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B. Q., Wong T. K. F., Von Haeseler A., Jermiin L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14 587–589. 10.1038/nmeth.4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov A. M., Darriba D., Flouri T., Morel B., Stamatakis A. (2019). RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 35 4453–4455. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Shashni S., Kumar P., Pant D., Singh A., Verma R. K. (2021). Phytochemical constituents, distributions and traditional usages of Arnebia euchroma: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 271:113896. 10.1016/j.jep.2021.113896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal M., Samant S., Kumar R., Sharma L., Paul S., Dutt S., et al. (2020). Population ecology and niche modelling of endangered Arnebia euchroma in Himachal Pradesh, India-An approach for conservation. Med. Plants-Int. J. Phytomed. Rel. Indust. 12 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wang S., Jing Y., Wang L., Zhou S. (2013). A modified CTAB protocol for plant DNA extraction. Chin. Bull. Bot. 48 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liao M., Yan P., Liu X., Du Z., Jia S., Aybek R., et al. (2020). Spectrum-effect relationship for anti-tumor activity of shikonins and shikonofurans in medicinal Zicao by UHPLC-MS/MS and chemometric approaches. J. Chromatograph. B 1136:121924. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2019.121924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhao C., Guo L., Ma S., Zheng J., Wang J. (2020). The plant original identification of Inner Mongolia Arnebia radix based on morphology and DNA barcoding. Res. Squ. 2020:6478. [Google Scholar]

- Ma S.-J., Geng Y., Ma L., Zhu L. (2021). Advances in Studies on Medicinal Arnebiae Radix. Mod. Chin. Med. 23 177–184. 10.1016/j.fitote.2019.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestre F. T., Salguero-Gómez R., Quero J. L. (2012). It is getting hotter in here: determining and projecting the impacts of global environmental change on drylands. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 367 3062–3075. 10.1098/rstb.2011.0323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdy M., Ou L., Yu H., Chen R., Zhou Y., Hassan H., et al. (2019). Pan-plastome approach empowers the assessment of genetic variation in cultivated Capsicum species. Horticult. Res. 6:108. 10.1038/s41438-019-0191-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H.-H., Zhang M.-L. (2011). Phylogeography of Lagochilus ilicifolius (Lamiaceae) in relation to Quaternary climatic oscillation and aridification in northern China. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 39 787–796. [Google Scholar]

- Park I., Yang S., Song J.-H., Moon B. C. (2020). Dissection for floral micromorphology and plastid genome of valuable medicinal borages arnebia and lithospermum (Boraginaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 11:606463. 10.3389/fpls.2020.606463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M. A. R., Bender D., et al. (2007). PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Human Genet. 81 559–575. 10.1086/519795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J., Zhang X., Chen B., Huang F., Xu K., Huang Q., et al. (2020). Comparison of the cytoplastic genomes by resequencing: insights into the genetic diversity and the phylogeny of the agriculturally important genus Brassica. BMC Genom. 21:480. 10.1186/s12864-020-06889-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H., Yang Y., Dong S., He Q., Jia Y., Zhao L., et al. (2017). Threatened species list of China’s higher plants. Biodiv. Sci. 25:696. 10.1186/s13002-020-00420-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. (1996). Se-Al: sequence alignment editor. version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A., Suchard M., Xie D., Drummond A. (2014). Tracer v1. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Teslenko M., Van Der Mark P., Ayres D. L., Darling A., Hohna S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J., Ferrer-Mata A., Sanchez-Delbarrio J. C., Guirao-Rico S., Librado P., Ramos-Onsins S. E., et al. (2017). DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34 3299–3302. 10.1093/molbev/msx248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samant S. S., Dhar U., Rawal R. S. (1998). Biodiversity status of a protected area in West Himalaya: askot wildlife sanctuary. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World Ecol. 5 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E. N., Ruhlman T. A., Weng M.-L., Khiyami M. A., Sabir J. S. M., Hajarah N. H., et al. (2017). Plastome-wide nucleotide substitution rates reveal accelerated rates in Papilionoideae and correlations with genome features across legume subfamilies. J. Mol. Evol. 84 187–203. 10.1007/s00239-017-9792-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J., Lickey E. B., Beck J. T., Farmer S. B., Liu W. S., Miller J., et al. (2005). The tortoise and the hare II: Relative utility of 21 noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences for phylogenetic analysis. Am. J. Bot. 92 142–166. 10.3732/ajb.92.1.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J., Lickey E. B., Schilling E. E., Small R. L. (2007). Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. Am. J. Bot. 94 275–288. 10.3732/ajb.94.3.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ślipiko M., Myszczyński K., Buczkowska K., Bączkiewicz A., Szczecińska M., Sawicki J. (2020). Molecular delimitation of European leafy liverworts of the genus Calypogeia based on plastid super-barcodes. BMC Plant Biol. 20:243. 10.1186/s12870-020-02435-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedmark J. E. E., Rydin C., Razafimandimbison S. G., Khan S. A., Liede-Schumann S., Bremer B. (2008). A phylogeny of Urophylleae (Rubiaceae) based on rps16 intron data. Taxon 57 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. A., Donoghue M. J. (2008). Rates of molecular evolution are linked to life history in flowering plants. Science 322 86–89. 10.1126/science.1163197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M. (1992). The chloroplast genome. Plant Mol. Biol. 19 149–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Corrales S., García-Botero C., Garcés-Cardona F., Ramírez-Ríos V., Villanueva-Mejía D. F., Álvarez J. C. (2021). The complete chloroplast genome of plukenetia volubilis provides insights into the organelle inheritance. Front. Plant Sci. 12:60. 10.3389/fpls.2021.667060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend M., Gottschling M., Selvi F., Hilger H. H. (2009). Marbleseeds are gromwells – Systematics and evolution of Lithospermum and allies (Boraginaceae tribe Lithospermeae) based on molecular and morphological data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 52 755–768. 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S., Xu P., Deng Y., Dai X., Zhao L., Heider B., et al. (2021). Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes of cultivars and wild species of sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam). BMC Genom. 22:262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Li P., Ren G., Wang Y., Jiang D., Liu C. (2021). Authentication of three source spices of arnebiae radix using DNA Barcoding and HPLC. Front. Pharmacol. 12:14. 10.3389/fphar.2021.677014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Yu Q., Zhang Q., Hu X., Hu J., Fan B. (2017). Regional-scale differentiation and phylogeography of a desert plant Allium mongolicum (Liliaceae) inferred from chloroplast DNA sequence variation. Plant Syst. Evol. 303 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S., Poczai P., Hyvönen J., Tang J., Amiryousefi A. (2020). Chloroplot: an online program for the versatile plotting of organelle genomes. Front. Genet. 11:124. 10.3389/fgene.2020.576124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G.-L. (1982). A study on the taxonomy and distribution of Lithospermum and Arnebia in China. J. Syst. Evol. 20 323–328. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of the five Arnebia species chloroplast genomes using mVISTA.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the GenBank, accession number ON529903-ON529958.