Abstract

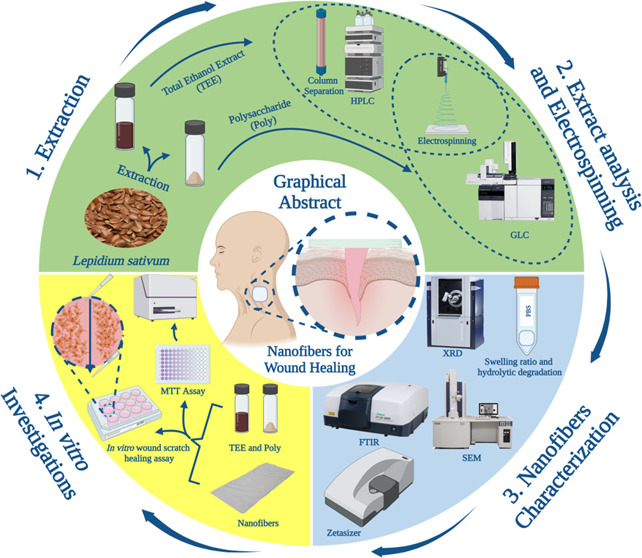

Lepidium sativum L. (Garden cress/Hab El Rashad) (Ls), family Brassicaceae, has considerable importance in traditional medicine worldwide because of its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Ls fruits were used in Ayurvedic medicines as a useful drug for injuries, skin, and eye diseases. The aim of this study was to examine the effectiveness of the total ethanol extract (TEE) and polysaccharide (Poly) of Ls seeds loaded on poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) nanofibers (NFs) as a wound healing dressing and to correlate the activity with the constituents of each. TEE and Poly were phytochemically analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative analysis proved the presence of phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, sterols, triterpenes, and mucilage. Meanwhile, quantitative determinations were carried out spectrophotometrically for total phenolic and total flavonoid contents. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for TEE identified 15 phenolic acids and flavonoid compounds, with gallic acid and catechin as the majors. Separation, purification, and identification of the major compounds were achieved through a Puriflash system, column Sephadex LH20, and spectroscopic data (1H, 13C NMR, and UV). Eight compounds (gallic acid, catechin, rutin, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside, quercetin, and kaempferol) were obtained. Gas–liquid chromatography (GLC) analysis for Poly identified 11 compounds, with galactose being the main. The antioxidant activity for both extracts was measured by three different methods based on different mechanisms: 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP), and 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS). TEE has the highest effectiveness as an antioxidant agent with IC50 82.6 ± 8.35 μg/mL for DPPH and 772.47 and 758.92 μM Trolox equivalent/mg extract for FRAP and ABTS, respectively. The PVA nanofibers (NFs) for each sample were fabricated by electrospinning. The fabricated NFs were characterized by SEM and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR); the results revealed successful encapsulation of TEE and Poly in the prepared NFs. Moreover, the swelling index of TEE in the prepared NFs shows that it is the most appropriate for use as a wound dressing. Cytotoxicity studies indicated a high cell viability with IC50 216 μg/mL and 1750 μg/mL for TEE and Poly, respectively. Moreover, the results revealed that nanofibers possess higher cell viability compared to solutions with the same sample quantities: 9-folds for TEE and 4-folds for Poly of amount 400 μg. The in vitro wound healing test showed that the TEE nanofibers performed better than Poly nanofibers in accelerating wound healing, with 90% for TEE, more than that for the Poly extract (82%), after 48 h. These findings implied that the incorporation of TEE in PVA nanofibers was more efficient than incorporation of Poly in improving the biological activity in wound healing. In conclusion, the TEE and polysaccharides of L. sativum L seed are ideal candidates for nanofibrous wound dressings. Furthermore, the contents of phenolic acids and flavonoids in TEE, which have potential antioxidant activity, make the TEE of L. sativum more favorable for wound healing dressing.

Introduction

The skin is the largest organ in the body and serves as one of the body’s first lines of defense against pathogens.1 However, the skin can be injured by chemical and physical factors, and certain diseases (including diabetes).2 Wound healing is a complex process, and it aims to restore the normal anatomic structure and function of the skin. Although the skin can regenerate spontaneously, the healing process is slow for some wounds.3 To address this problem, many researchers have recently focused on developing wound dressings by combining medicinal plant extracts with natural polymer-based electrospun nanofibers (NFs).4 Such dressings can be made by electrospinning a plant extract into polymeric nanofibers.5 Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) is one of the most popular synthetic polymers that is used because of its electrospinning ability and formation of excellent nanofibers (NFs).6 PVA is very beneficial for biomedical applications, in particular, wound dressing and tissue engineering, owing to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and nontoxicity.7 The electrospun nanofibers have unique characteristics, which include a large surface area to volume, high air permeability, and high absorption of secretions from the wound, as well as the possibility of releasing gradually the drug agents loaded on nanofibers.8 All of these make nanofibers good candidates that mimic the morphology of the extracellular matrix of the damaged tissue.9 This study is based on Lepidium sativum (Ls) seeds, also commonly known as garden cress; they are also called “Hab rchad” in Egypt. They belong to the Brassicaceae family. The seeds contain 35–54% carbohydrates, 27% protein, 14–26% fat, and 8% crude fiber.10 The carbohydrates of Ls seeds include 90% non-starch polysaccharides (Poly) and 10% starch.11 Phytochemical study of the plant extract reveals the presence of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, tannins, glycosides, polyphenols, lectin, and mucilage.12 The Ls seed was reported as a rich source of minerals such as potassium, zinc, phosphorus, and calcium, so it was considered to be an important nutraceutical seed for nutrient enrichment.13 It also contains a sufficient amount of vitamins, mainly thiamine, riboflavin, and niacin, which work as cofactors and help in body metabolism.14 The Ls seeds extract also contains natural antioxidants such as tocopherols, which represent major phenolic compounds in Morocco.15 Valuable folk medicine uses were reported for Ls as therapy for inflammatory diseases including arthritis, hepatitis, and diabetes mellitus.16 One of the traditional uses of L. sativum in Saudi Arabia and other Arabic parts was for accelerating bone fracture healing and as an alternative to prescribed supplements.17 Nanofibers containing the extract can help in the management of patients with wound healing problems by the production of the wound dressing. So, the present work aims to examine the effectiveness of electrospun PVA/Ls seed total ethanol extract (TEE) and Poly as a wound healing dressing. The spinning conditions of NFs were optimized in detail, and both extracts and NFS were subjected to a panel of bio-evaluation assays, including antioxidant, cytotoxicity, and wound scratching. The constituents of each extract were also examined.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Reagents

Plant Material

Seeds of L. sativum L. were purchased from a local store, Sinai, Egypt. They were identified and authenticated by Dr. Therese Labib, Consultant of Plant Taxonomy at the Ministry of Agriculture and Ex-director of the Orman Botanical Garden, Giza, Egypt. Seeds were shade-dried and ground to a fine state. Two samples, namely total ethanol extract (70%) (TEE) and polysaccharide (Poly), were prepared from the powdered seeds.

Materials for Nanofiber

Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA, MW = 72,000 g/mol; 86% hydrolyzed) was obtained from Lobachemie (India). Citric acid anhydrous (CA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (GmbH, Steinheim, Germany). Samples of TEE and Poly were obtained from Ls seeds.

Reagents for Cytotoxicity and Wound Healing Assay

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (1×), sodium pyruvate, l-glutamine, 0.4% trypan blue, and 0.25% trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (1×) were obtained from Gibco, Life Technologies (U.K.), whereas penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) was obtained from Lonza (Germany). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Life Science Production (LSP, U.K.) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) from SERVA Electrophoresis GmbH (Germany). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) tablets (pH 7.4) were received from LobaChemie Pvt. Ltd (India).

Extraction

Preparation of Total Ethanol Extract (70%) from L. sativum Seeds

The extract (TEE) was prepared by the maceration process. Powdered seeds (250 g) were macerated in 1 L of ethanol 70% and stored at room temperature for 3 days. The process was repeated 3 times.

Preparation of Polysaccharides from L. sativum Seeds

One hundred grams of powdered seeds was mixed with one liter of distilled water, slightly acidified with hydrochloric acid (pH 3.5), stirred for 12 h at about 28 ° C, and left to stand for another 12 h. The solution was passed through folded muslin. The process was repeated three times; the combined water extract was concentrated under vacuum to 1/3 of its volume on a rotary evaporator at 50 °C, and the polysaccharide was precipitated from the combined aqueous extract by adding slowly, while stirring, 4 volumes of ethanol.18

The precipitate obtained by centrifugation was washed several times with ethanol till it was free from chloride ions. It was then vigorously stirred in absolute acetone, filtered, and dried in a vacuum desiccator over anhydrous calcium chloride. The precipitated polysaccharides (Poly) were submitted to a gel formation test to detect their nature.19

Phytochemical Analysis

Qualitative Phytochemical Screening

Total ethanol extract (70%) was analyzed by phytochemical reactions for the usual plant secondary metabolites. The screening was performed for carbohydrates, terpenoids/steroids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, cardiac glycosides, proteins/amino acids, alkaloids, and anthraquinones.20−22 The precipitate formation or the color intensity was used as the analytical response to these tests.

Quantitative Estimation of the Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents of TEE (70%)

All assays were performed spectrophotometrically using the microplate reader FluoStar Omega relating to pre-established standard calibration curves. Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteau method, and the flavonoid content was determined by measuring the intensity of the color developed when flavonoids were complexed with aluminum chloride reagent. The results were expressed as gallic acid (GAE) and rutin (RE) equivalents, respectively, as described by Attard.23

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis of TEE of the L. sativum Seed

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of TEE was carried out using an Agilent 1260 series (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) with a diode array detector. The separation was carried out using a Kromasil C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm i.d., 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of water (A) and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The mobile phase was programmed consecutively in a linear gradient as follows: 0 min (82% A); 0–5 min (80% A); 5–8 min (60% A); 8–12 min (60% A); 12–15 min (82% A); and 15–16 min (85% A). The multi-wavelength detector was monitored at 280 nm. The injection volume was 10 μL for each of the sample solutions. The column temperature was maintained at 35 °C. This analysis enabled the characterization of phenolic compounds based on their retention time and UV spectra.

Separation and Identification of Compounds of TEE

The TEE of L. sativum seeds (3 g) was subjected to preparative separation by a PuriFlash 4100 system, Interchim Software 5.0 (Interchim; Montluçon, France), with a PDA-UV-Vis detector at 190–840nm. The separation was carried out using a C18-HP column (30 μm). The mobile phase consisting of 1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) was programmed in a gradient elution. The process led to 130 fractions, which were inspected by paper chromatography 1MM (PC 1MM) and using butanol/acetic acid/water (BAW) 4:1:5 and acetic acid (HOAc) 15% as the running system. The similar fractions were combined to obtain eight substantial fractions (sub-fractions A–H). These fractions were subjected to different chromatographic techniques, including 3MM preparative paper chromatography and repeated Sephadex LH-20 column using eluents of different polarities, which led to the isolation and purification of eight compounds. The isolated compounds were structurally elucidated through different investigations: physical, chemical, chromatographic, and spectral data (UV, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and mass spectroscopy (MS)).24−26

Gas–Liquid Chromatography (GLC) Analysis for the Polysaccharide of L. sativum

Preparation of the Sample

The polysaccharide powder was subjected to acid hydrolysis according to the reported method by Chrums and Stephen.27 Briefly, the powder (100 mg) was heated in sulfuric acid in a sealed tube (2 mL, 0.5 M, 20 h) in a boiling water bath. At the end of hydrolysis, a flocculent precipitate was noticed. This was filtered off and the filtrate was freed of sulfate ion (SO42–) by precipitation with barium carbonate.

Part of the hydrolyzate polysaccharide was silylated according to the reported method.28 Briefly, the hydrolyzate solution (0.5 mL) was evaporated in small screw-topped septum vials to dryness under a stream of nitrogen at 40 °C. When almost dry, isopropanol (0.5 mL) was added and the drying was completed under the stream of nitrogen until a dry solid residue was obtained. Hydroxylamine hydrochloride in pyridine (0.5 mL, 2.5%) was added, mixed, heated (30 min, 80 °C), and allowed to cool. The silylating reagent (trimethylchlorosilane: N,O-bis-(trimethylsilyl) acetamide, 1:5 by volume) (1 mL) was added, mixed, and heated (30 min, 80 °C).

GLC Analysis

Silylated polysaccharide hydrolyzate (1 μL) was analyzed using the GLC apparatus (HP 6890) under the following conditions: column: ZB-1701, 30 m × 0.25 m × 0.25 μm; stationary phase: 14% cyanopropyl phenyl methyl polysiloxane; carrier gas: helium (with flow rate: 1.2 mL/min, pressure: 10.6 psi, and velocity: 41 cm/s); injector chamber temperature: 250 °C; back inlet with split ratio: 1:10, split flow: 11.9 mL/min, total flow: 18.7 mL/min, gas saver flow: 120 mL/min, and average time: 20 min; oven with 150 °C as initial temp., 2 min as initial time, 7 °C/min rate, and 200 °C as final temp., 20 min as the final time; and an FID detector (temp.: 270 °C, air flow: 450 mL/min, and H2 flow: 40 mL/min).

Antioxidant Activity

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Assay

Evaluation of the radical scavenging activity of TEE and Poly of L. sativum was carried out by the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay according to the method of Boly et al.29 Briefly, a freshly prepared DPPH reagent (0.1% in methanol, 100 μL) was added to each sample (100 μL) in a 96-well plate (n = 3), and the reaction was incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. At the end of the incubation time, the resulting reduction in DPPH color intensity was measured at 540 nm.30 Data are represented as means ± standard deviation (SD) according to the following equation

| 1 |

where A0 is the absorbance of the blank and A1 is the absorbance of the extract.

The IC50 value is defined as the concentration of the extract or standard that allows a 50% reduction of DPPH. Lower IC50 values indicate greater effectiveness of the antioxidant power of the extract. The samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Reducing Power (FRAP Assay, Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power)

The ferric reducing ability assay was carried out for the TEE and Poly of L. sativum according to the method of Benzie et al.,31 with minor modifications carried out in microplates. It is based on the rapid reduction of ferric-tripyridyltriazine (FeIII-TPTZ) by the antioxidants present in the samples forming ferrous-tripyridyltriazine (FeII-TPTZ). Briefly, the TPTZ reagent (300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ in 40 mM HCl, and 20 mM FeCl3, in the ratio of 10:1:1 v/v/v, respectively) was freshly prepared. A volume of 190 μL of the TPTZ reagent was mixed with 10 μL of the sample in a 96-well plate (n = 3); the reaction was incubated (30 min) at room temperature in the dark. The resulting blue color at the end of the incubation time was measured at 593 nm using the microplate reader FluoStar Omega.30 The data were represented as means ± SD. The increase in absorbance of the reaction medium indicates the increase in iron reduction. The ferric reducing ability of the samples was presented as μM TE/mg sample (Trolox equivalent per milligram sample) using the linear regression equation extracted from the Trolox calibration curve (linear dose–response curve of Trolox).

3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic Acid (ABTS) Assay

The assay was carried out according to the method of Arnao et al.,32 with minor modifications carried out in microplates. The 2,2-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assay measures the relative ability of antioxidants to scavenge the ABTS generated in the aqueous phase, as compared with the Trolox (water-soluble vitamin E analogue) standard. Briefly, ABTS (192 mg) was dissolved in distilled water and transferred to a volumetric flask (50 mL); then the volume was completed with distilled water. One milliliter of the prepared solution was added to 140 mM potassium persulfate (17 μL) and the mixture was kept for 24 h in the dark. After that, 1 mL of the reaction mixture was diluted to 50 mL with methanol to obtain the final ABTS dilution used in the assay. A volume of 190 μL of the freshly prepared ABTS reagent was mixed with the sample (10 μL) in a 96-well plate (n = 6); the reaction was incubated for 120 min at room temperature in the dark. The decrease in ABTS color intensity at the end of the incubation time was measured at 734 nm.30 The data are stated as means ± SD according to the following equation:

| 2 |

where ‘avg’ is average. The results of ABTS•+ radical assays were presented as μM TE/mg sample [Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC)] using Trolox as a standard reference.

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel was used as the software for data analyses, whereas IC50 values were calculated using Graph pad Prism version 5.33

Preparation of Nanofibers

Optimization of PVA/TEE and PVA/Poly Nanofibers

The TEE and Poly of L. sativum (0.3, 0.6, and 1%, w/v) were dispersed separately in PVA solution (10%, w/v) with continuous stirring for 6 and 18 h, respectively, at 50 °C in a closed vial to enhance the homogeneity of the mixture solution. Citric acid (CA) (1.5%, w/v %) was added to the solution, which was electrospun into the NFs by an electrospinner (NANON-01A, MECC, Japan). The produced NFs were thermally treated at 80 °C for 18 h, then at 100 °C for 6 h.

Instrumental Characterization of PVA/TEE and PVA/Poly Nanofibers

SEM: the successful formation of the uniform and appropriate surface morphology of NFs was investigated by SEM (FS SEM, Quattro S, Thermo Scientific). FTIR: the nature of binding among the nanofibrous scaffold compositions was revealed by FTIR (Bruker Vertex 70, Germany), at wavenumbers ranging between 400 and 4000 cm–1. ζ-Measurements: the surface charge of the prepared nanofibrous scaffolds was measured by a nano-zetasizer apparatus (Malvern Instruments, U.K.).

Physicochemical Characterization of PVA/TEE and PVA/Poly Nanofibers

Swelling Study

The swelling ratios of both types of nanofibers were studied in distilled water at 37 °C and the swelling % of NFs was calculated by the equation34

| 3 |

where Ws is the weight of the swollen nanofiber and We is the weight of nanofibers after immersion.

In Vitro Hydrolytic Degradation

The weight loss pattern of the prepared nanofiber samples was evaluated by investigating the in vitro hydrolytic degradation in PBS solution. Dried nanofiber samples were weighed and immersed in 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) (pH 7.4, 37 °C). At specific time intervals, samples were removed, wiped, and gently dried at ambient temperature, then reweighed.35

| 4 |

where W0 is the original weight of the nanofiber sample, and Wt is the weight of nanofibers after a specific incubation time.

In Vitro Bio-Evaluation Tests

Cell Culture

The adherent Vero cells (normal African green monkey kidney epithelial cells) originated from ATCC CCL-81 were grown and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). High Glucose (4500 mg/L d-Glucose) was enriched with 200 units/mL penicillin, 200 μg/mL streptomycin, fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%), l-glutamine (2 mM final concentration), and sodium pyruvate (1 mM final concentration). The cells were maintained in monolayer culture in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator at 37 °C. Cells were subcultured twice a week.

In Vitro Cell Viability

TEE and Poly were tested for cytotoxicity using Vero cells by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay.36 Firstly, Vero cells were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well and incubated under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After 24 h, the media was replaced with fresh media containing serial 2-fold dilutions of TEE and Poly starting from 200 to 0.39 μg/mL. After 48 h of incubation, the cells were treated with MTT dye for 4 h and the formazan crystals were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance was read at 570 nm using a multimode microplate reader (CLARIOstar Plus, BMG LABTECH, Germany). The cytotoxicity of the prepared nanofibers (PVA, PVA-TEE and PVA-PS) was determined with the same assay. The nanofibers were cut into circular shapes and sterilized under UV for 2 h. The relative cell viability was determined by the formula

| 5 |

In Vitro Scratch Wound Assay

The wound-healing effect of the prepared nanofibers was tested in vitro based on the previously described method.37 Cells were seeded into a 12-well tissue culture plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. After the cells formed a confluent monolayer (70–80%), a scratch was applied using a 200 μL pipette tip on the cell sheet to form a cell-free area. After scratching, the wells were gently washed with PBS twice to remove any cell debris. The prepared NF scaffolds were then immersed directly in the wells and the rate of wound closure was monitored after 0, 24, and 48 h by an inverted fluorescence microscope (Axio observer 5, Carl Zeiss, Germany). The closure rate was determined by measuring the wound gap area according to the formula

| 6 |

Results and Discussion

Phytochemical Analysis

Phytochemical Screening

The healthy properties of such edible seeds are due to the presence of a variety of phytoconstituents such as polysaccharides, flavonoids, glycosides, phenolics, saponins, tannins etc.38 The preliminary screening tests were useful in the detection of these bioactive constituents and in subsequently facilitating their quantitative estimation.

The results of phytochemical screening listed in Table 1 revealed the presence of a wide array of chemicals, including carbohydrates, steroids, flavonoids, phenolics, tannins, proteins/amino acids, and alkaloids in the TEE. These results are in agreement with the published data of Sharma39 and Yadav et al.40

Table 1. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening Tests in the Total Ethanol Extract (70%) (TEE) of L. sativum Seeds.

| phytochemical constituents | results |

|---|---|

| carbohydrates (reducing sugars) | +++ |

| steroids and/or terpenoids | + |

| flavonoids | + |

| phenolics | ++ |

| tannins | ± |

| cardiac glycosides | – |

| proteins/amino acids | + |

| alkaloids | ± |

| anthraquinones | – |

| saponins | – |

| +++ abundant | |

| ± traces | |

| – absent |

Yield, Total Phenolic, and Total Flavonoid Contents of the TEE of L. sativum Seeds

The yield of TEE and poly was 20/100 g seeds and 30/100 g seeds, respectively. The amounts of total phenols and total flavonoids were measured in the TEE of Ls seeds. The measurements were done using the linear regression equation of the calibration curve, using gallic acid and rutin as standards. The total phenolic and total flavonoid contents were 54.83 mg GAE/g extract and 10.01 mg RE/g extract, respectively. These results were compatible with those reported by Chatoui et al.41 Phenolics have a broad spectrum of biological activities, including radical scavenging, antiallergic, and antimicrobial.42

HPLC Analysis of TEE

The HPLC analysis of TEE revealed the identification of fifteen compounds: eleven phenolic acids and four flavonoids (Table 2). The main compounds detected were gallic acid (14.8227%) and caffeic acid (10.4147%) as phenolic acids and catechin (10.1689%) and rutin (2.4268%) as flavonoid compounds. The obtained results were similar to those reported by Abd El-Salam et al. and Panwar et al. as gallic acid and catechin were the main phenolic acid and flavonoid, respectively.43,44

Table 2. HPLC Analysis of the TEE of L. sativum Seeds.

| no | Rt | compounds | area % | concn (μg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.133 | gallic acid | 14.8227 | 11712.47 |

| 2 | 3.807 | chlorogenic acid | 0.2030 | 138.89 |

| 3 | 4.108 | catechin | 10.1689 | 12672.16 |

| 4 | 4.566 | protocatechuic | 6.2717 | 682.15 |

| 5 | 5.111 | methyl gallate | 0.1614 | 21.00 |

| 6 | 5.350 | caffeic acid | 10.4147 | 3364.33 |

| 7 | 6.524 | ellagic acid | 2.7754 | 2889.52 |

| 8 | 6.930 | syringic acid | 0.7206 | 267.93 |

| 9 | 7.264 | rutin | 2.4268 | 2788.91 |

| 10 | 8.281 | coumaric acid | 0.1106 | 19.29 |

| 11 | 9.358 | vanillic acid | 2.7620 | 593.50 |

| 12 | 9.467 | ferulic acid | 2.8781 | 863.53 |

| 13 | 9.927 | naringenin | 0.0394 | 20.06 |

| 14 | 12.229 | taxifolin | 1.2344 | 752.37 |

| 15 | 13.423 | cinnamic acid | 0.1451 | 13.28 |

Structural Elucidation of the Isolated Compounds from TEE

Chromatographic investigation of the TEE of L. sativum seeds led to the isolation and identification of eight compounds: gallic acid (1), catechin (2), quercetin-3-O-α-rhamnosyl (1‴ → 6″)-β-glucoside (rutin) (3), kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside (4), quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside (5), kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside (6), quercetin (7), and kaempferol (8); these compounds were reported previously in the plant.45

The identification of each compound was done according to their Rf values, color reactions, acid hydrolysis, UV spectrophotometry using chemical shifts (aluminum chloride (AlCl3), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium methoxide solution (NaOMe), sodium acetate (NaOAc), and boric acid (H3Bo4)), and electron ionization mass spectrometry (EI/MS). 1H and C13 NMR and Co-PC were done with the reference samples; then, comparison of their spectroscopic data was done with previously reported values.24−26

Gallic Acid

Off-white amorphous powder, melting point (mp) 254–256 °C. It appears as a blue light fluorescence spot under UV on PC, which turned to dark blue when sprayed with FeCl3 solution; EI/MS showed a molecular ion peak [M – H]− at m/z 169; the UV at λ max nm (MeOH) (270) confirmed a phenolic acid skeleton.26 The 1H NMR spectrum (Acetone-d6, 400 MHz) revealed the presence of two equivalent aromatic protons (H2–H6) at δ 7 ppm.

Catechin

Off-white amorphous powder, soluble in methanol, dark in color under UV light (λ 254 nm), and converted to faint yellow after exposure to ammonia vapor. It turned to pink to purple color on using a vanillin sulfuric acid spray reagent. The UV spectrum data exhibited one UV maxima at 280 nm in the MeOH spectrum. The 1H NMR spectrum showed signals of aromatic proton at different chemical shifts δ (ppm). Three protons of ring B, H2′, appeared at δ 6.89 (J(H-2′,H-6′) = 2 Hz), as a doublet, due to meta-coupling with H6′. H6′ appeared at δ 6.77, as a doublet of doublet due to meta-coupling with H2′ (J(H2′, H6′) = 2 Hz) and ortho-coupling with H5′ (J(H5′, H6′) = 8.05 Hz), which appeared at δ 6.81 as a doublet (J(H-5′, H-6′) = 8.05 Hz). The two protons related to ring A, H-6 and H-8, appeared at δ 5.91 and 5.99, respectively, with J = 2, indicating that they are meta-coupled. The protons at δ 4.56 appeared as a doublet with J(H-2, H-3a) = 7.8 Hz for H-2, while at δ 4.00, as a multiplet for H-3; peaks appeared at δ 2.53 and 2.89 each for one proton, (H-4a) and (H-4e), and appeared as a doublet of doublet with J(H-4a, H-3a) = 8.50 Hz, J(H-4a, H-4e) =16.10 Hz, J (H-4e, H-3a) = 5.5 Hz, and J (H-4e, H-4a) = 16.1Hz. The 13C NMR spectrum showed peaks at δ 28.5 for (C-4), 68 for (C-3), 82.1 for (C-2), 94.5 for (C-6), 95.8 for (C-8), 101 for (C-2′), 115.3 for (C-5′), and 116.1 for (C-6′) and other aromatic peaks at δ 131.4, 144.9, 145.7, 156.8, 157.9, and 158.1. The UV spectrum agreed with that published for catechin (Flavan-3-Ol).461H NMR and 13C NMR spectral data were similar with those published for Catechin.47

Quercetin-3-O-α-Rhamnosyl (1‴ → 6″) β-Glucoside (Rutin)

Yellowish green powder, soluble in methanol, deep purple spot on PC under UV light, turned to fluorescent yellow when fumed with NH3 or spraying with AlCl3, Rf values of 0.40 and 0.67 in BAW, and 15% HOAc. It yields quercetin as an aglycone, and rhamnose and glucose as the sugar moieties (Co-PC with authentic samples) on complete acid hydrolysis. UV at λ max nm MeOH: 258, 300, 356; NaOMe: 271, 326 sh, 410; AlCl3: 275, 305 sh, 420; AlCl3/HCl: 268, 301 sh, 358, 400; NaOAc: 271, 324 sh, 380; NaOAc/H3BO3: 262, 379. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ ppm 7.55 (2H, m H-2′/6′), 6.85 (1H, d, J = 9 Hz, H-5′), 6.40 (1H, d, J = 1.50 Hz, H-8), 6.20 (1H, J = 1.50 Hz, H-6), 5.35 (1H, d, J = 7.04 Hz, H-1″), 4.39 (1H, s, H-1‴), 3.90–3.20 (m, remaining sugar protons), 0.99 (3H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, H-6‴).

Kaempferol-3-O-Rutinoside

Yellow powder, 1H NMR (MeOD, 400 MHz): aromatic protons at δ ppm 8.04 (2H, d, J = 8.6, H-2′,6′), 6.88 (2H, d, J = 8.6, H-3′,5′); 6.21 (1H, d, J = 2.0, H-6), 6.41 (1H, d, J = 2.0, H-8), 5.14 (1H, d, J = 7.4, β sugar), 4.51 (1H, s, rhamnose, H-1), 0.88 (3H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, rhamnosyl CH3), 3.25–3.82 (sugar protons). 13C NMR (MeOD, 100 MHz): δ 159.56 (C-2), 135.66 (C-3), 179.55 (C-4), 163.15 (C-5), 100.12 (C-6), 166.15 (C-7), 95.05 (C-8), 158.70 (C-9), 105.84 (C-10), 121.00 (C-1′), 132.50 (C-2′), 116.30 (C-3′), 161.61 (C-4′), 116.30 (C-5′), 132.50 (C-6′), 104.76 (C-1″), 74.06 (C-2″), 78.31 (H-3″), 71.61 (H-4″), 78.04 (H-5″), 68.73 (H-6″), 102.56 (H-1‴), 72.24 (H-2‴), 72.49 (H-3‴), 73.61 (H-4‴), 69.88 (H-5‴), 18.03 (H-6‴, CH3).

Quercetin-3-O-Rhamnoside

Yellow powder, purple spot on PC under UV light, turned to fluorescent yellow when sprayed with NH3 vapor or spraying with AlCl3, Rf values of 0.68 and 0.62 in BAW, and 15% HOAc. Complete acid hydrolysis yields quercetin as an aglycone in the organic layer and rhamnose as a sugar moiety in the aqueous layer (Co-PC with authentic samples). UV at λ max nm MeOH: 256, 265 sh, 352; NaOMe: 272, 324 sh, 390; AlCl3: 275, 300 sh, 428; AlCl3/HCl: 270, 300 sh, 354, 402; NaOAC: 270, 320 sh, 370; NaOAC/H3BO3: 260, 368. 1H NMR aglycone moiety: δ (ppm) 7.4 (2H, m, H-2′, H-6′), 6.82 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-5′), 6.35 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-8), 6.20 (1H, d, J = 1.5 Hz, H-6). Sugar moiety: δ (ppm) 5.40 (1H, s, H-1″), 3.5–3.2 (m, sugar protons), 0.98 (3H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, rhamnosyl CH3).

Kaempferol-3-O-Rhamnoside

Yellow amorphous powder, 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) (δ ppm): δ 7.84 (2H, dd, J = 8.6, 2.5 Hz, H-2′ and H-6′), 7.00 (2H, dd, J = 8.6, 2.5 Hz, H-3′ and H-5′), 6.45 (1H, d, J = 2.3 Hz, H-8), 6.25 (1H, d, J = 1.8 Hz, H-6), 5.52 (1H, d, J = 1.4 Hz, H-1″), 4.22 (1H, d, J = 1.4 Hz, H-2″), 3.70, 3.30 (remaining sugar protons), and 0.90 (3H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, Me-6″). 13C NMR (100 MHz, MeOD), δ (ppm): δ 178.5 (C-4), 164.2 (C-7), 162.2 (C-5), 160.1 (C-9), 157.6 (C-4′), 157.2 (C-2).

Quercetin

Light yellow spot on PC intensified on exposure to NH3 or spraying with AlCl3, Rf values of 0.67 and 0.08 in BAW, and 15% HOAc; UV at λ max nm MeOH: 256, 265 sh, 352; NaOMe: 272, 322 sh, 394; AlCl3: 274, 300 sh, 432; AlCl3/HCl: 271, 300 sh, 353, 400; NaOAc: 270, 320 sh, 371; NaOAc/H3BO3: 262, 369.

Kaempferol

Yellow powder, soluble in methanol, mp 276–278 °C. It showed a deep purple color in UV light (λ 365 nm), converted to yellowish green on exposure to ammonia vapor, and intensified after spraying with a 5% AlCl3 reagent. The UV spectral data in methanol: λ367, 296 sh, 267, 255 sh. NaOMe: λ416, 323, 277. AlCl3/MeOH: 395, 349, 300 sh, 274. AlCl3/HCl/MeOH: 398, 352, 303 sh, 274. NaOAc/MeOH: 395, 302, 273. NaOAc/H3BO3/MeOH: 353, 320 sh, 290 sh, 266. NMR: δ 8.00 (2H, d, J = 8.84 Hz, H-2′/6′), 6.91 (1H, d, J = 8.84 Hz, H-3′/5′), 6.42 (1H, d, J = 1.84 Hz, H-8), 6.15 (1H, d, J = 1.84 Hz, H-6), δ 12.47 (1H, s, H-5).

GLC Analysis of Polysaccharide

Precipitation and purification of the polysaccharide content of L. sativum seeds gave 30% yield. The nature was confirmed by gel formation test and was found to be mucilage. GLC analysis of the polysaccharide content of the seeds (Table 3) revealed the identification of eleven sugars with galactose (21.884%) as the major one, followed by arabinose (20.476%), glucose (17.226%), galacturonic acid (11.039%), rhamnose (8.875%), mannose (4.316%), glucuronic acid (3.121%), xylose (1.527%), sorbitol (0.928%), mannitol (0.576%), and ribose (0.416%). These results were approximately similar to those of Abd El-Aziz et al.48 as Ls mucilage contains l-arabinose, d-xylose, d-galactose, l-rhamnose, and d-galacturonic acid as the major constituents with d-glucose and mannose as trace components. The Ls mucilage is widely used in traditional medicinal preparations in Saudi Arabia as a cough syrup. It also has anti-hyperglycemic properties, which help in diabetics.49

Table 3. Results of Polysaccharide Hydrolysate Analysis of L. sativum L. Seeds Determined by GLC.

| name | retention time | area % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | xylose | 19.994 | 1.527 |

| 2 | arabinose | 20.249 | 1.411 |

| 3 | ribose | 20.753 | 0.416 |

| 4 | rhamnose | 21.990 | 8.875 |

| 5 | mannitol | 23.410 | 0.576 |

| 6 | sorbitol | 24.855 | 0.928 |

| 7 | galactose | 26.209 | 21.884 |

| 8 | glucose | 26.522 | 17.226 |

| 9 | galacturonic acid | 26.960 | 11.039 |

| 10 | glucuronic acid | 27.646 | 3.121 |

| 11 | mannose | 28.977 | 4.315 |

Antioxidant Activity; DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS

Free radicals are generated normally in the body during vital processes. Usually there is a balance between the liberated free radicals and naturally occurring scavengers in the body such as glutathione; with the increase in age this situation becomes out of balance, leading to a higher percentage of liberated free radicals that target many organs in the body, causing harmful effects and various diseases. The TEE of L. sativum seeds was rich in polyphenol constituents, which could exhibit a higher antioxidant activity and prevent these diseases.50

Physical injuries of the skin lead to tissue damage or cut, and as a result, a series of biochemical reactions occur, which involve inflammation, proliferation, and migration of different types of immune system cells. Wound healing aims to restore the disrupted skin through contraction and closure of the wound to restore the skin as a functional barrier.51 The wound healing process may be restrained by the presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage the wound’s surrounding cells and facilitate microbial infection.52

Free radical scavengers are cytoprotective substances that have an essential role in the deactivation and removal of ROS, thus regulating the wound healing process.53

Plant-derived antioxidants such as tannins, phenolic acids, flavones, flavonols, catechins, and other compounds are natural free radical scavengers that help in protecting vital cells from the harmful effects of ROS. In the present study, the antioxidant activities of L. sativum seeds were found to be relatively high in TEE, which was rich in flavonoids and phenolic constituents; these constituents were responsible for the process of wound healing.54

Frankel and Meyer55 and Huang et al.56 mentioned that a single method is not adequate for evaluating the antioxidant capacity of extracts. Different methods can yield widely diverging results, so several methods with different mechanisms must be used. Evaluation of the antioxidant activities of both the TEE and Poly of Ls seeds was carried out by three methods (DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Antioxidant Activity of the Lepidium sativum Seeds’ TEE and Poly Using DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS Assays.

| iron reducing power (FRAP) | ABTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| antioxidant activity | free radical scavenging activity (DPPH) IC50 (μg/mL) | (μM Trolox equivalent/mg extract) | |

| TEE | 82.6 ± 8.35 | 772.47 | 758.92 |

| Poly | 100.0 ± 15.2 | 33.70 | 57.14 |

| Trolox | 42.42 ± 0.87 | ||

The IC50 of TEE and Poly in the DPPH radical scavenging assay was 82.6 ± 8.35 and 100.0 ± 15.2 μg/mL, respectively. A low IC50 value indicates a high antioxidant activity. The reducing power (FRAP) of TEE and polysaccharide was 772.47 and 33.70 μM Trolox equivalent/mg extract, respectively; thus, the extract showed a higher FRAP ability. The antioxidant ability to reduce the ABTS generated in the aqueous phase resulting in decreasing the color was 758.92 and 57.14 μM Trolox equivalent/mg extract for the total ethanol extract (70%) and polysaccharide of L. sativum seeds, respectively. Major flavonoids (catechin and quercetin) showed excellent radical scavenging activity,57 and the high radical scavenging activity of TEE compared to poly might be attributed to the presence of these compounds.

Preparation and Characterization of Nanofibers

Spinning Condition Optimization of PVA/TEE and PVA/Poly Nanofibers (NFs)

The formation of morphologically accepted NFs of both samples was found at a concentration of about 0.6% (wt/v %). The results revealed that the homogeneous and beads/droplets-free PVA and beads/droplets-free total ethanol L. sativum extract NFs have been produced with spinning conditions of voltage 27 kV, distance 15 cm, and feeding rate 0.1 mL/h, while PVA/polysaccharide NFs have been formed at voltage 30 kV, distance 15 cm, and feeding rate 0.2 mL/h. Thereafter, these electrospinning conditions allowed the formation of a Taylor cone that is essential for the formation of nanofibers.58

Instrumental Characterization of PVA/TEE and PVA/Poly Nanofibers

SEM

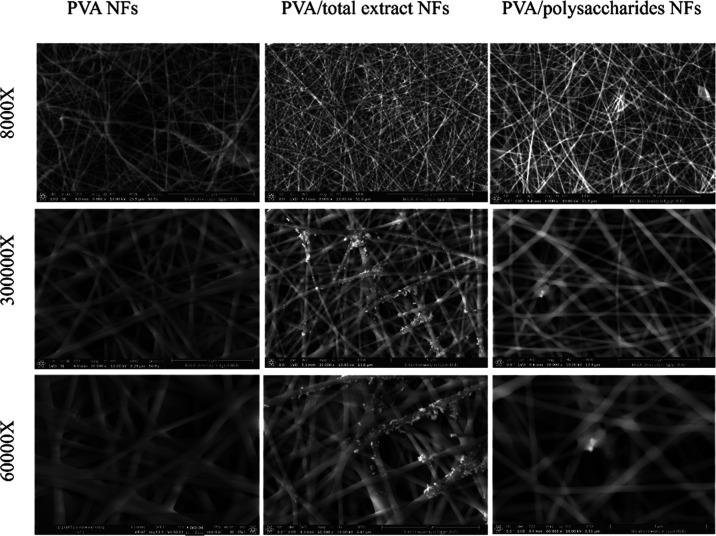

The morphologies of PVA, PVA/TEE-NFs, and PVA/Poly NFs are shown in Figure 1. SEM images of the three samples indicated the successful formation of uniform, non-woven, randomly oriented round-shaped with smooth surface, and continuous NFs.

Figure 1.

SEM images of PVA NFs, PVA/total ethanol extract NFs, and PVA/polysaccharide NF scaffolds with different original magnifications (×8000, ×30,000, and ×60,000) at 10 kV.

Interestingly, it was noted that the addition of TEE and Poly to PVA NFs decreased the average diameter of the nanofibers from 230 ± 40 to 140 ± 60 and 200 ± 50 nm, respectively. This reduction has arisen from the anionic nature of both extracts caused by carboxyl and hydroxyl groups.59 Such high charge density could decrease the diameter of nanofibers by increasing the electric conductivity and the ionic strength of the spinning solution, which in turn increases the elongation of the jet produced by the electrical field.60

Furthermore, some thick parts appeared in PVA/TEE-NFs and PVA/Poly NFs, indicating that both types of extracts are encapsulated in NFs. Similar results were previously mentioned by Fahami et al. when using L. sativum/PVA NFs for encapsulation of vitamin A.61

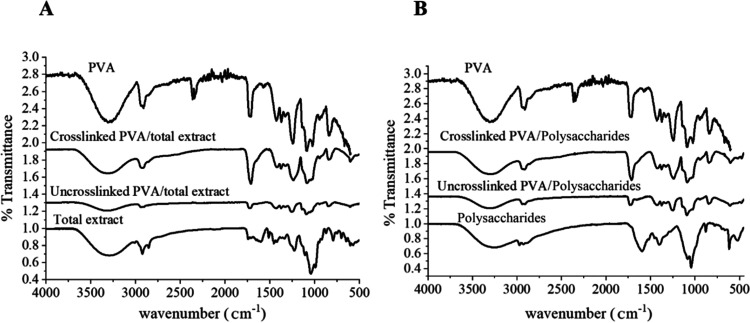

FTIR

FTIR spectra were studied to reveal the nature of the interaction between NF compositions and confirm the successful cross-linking reaction by CA. Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectra of pure PVA, cross-linked PVA/TEE L. sativum NFs, and cross-linked PVA/poly NFs. The PVA spectrum presents the characteristic bands detected at ν 3289, 2903, and 1713 cm–1 corresponding to hydroxyl, alkyl, and acetyl groups, respectively.9 Both the FTIR spectra of TEE and polysaccharides showed bands attributed to free hydroxyl groups and the bonded O–H of carboxylic acid at around 3297 and 3261 cm–1, respectively. Additionally, the appearance of strong bands around 2924 and 2854 cm–1 were attributed to the -aliphatic CH stretching and bending vibrations.62 In the spectra of TEE L. sativum, characteristic bands of flavonoids appeared at 1602 and 1455 cm–1 due to the stretching vibration of C=C, C=O, CH3, CH2, and aromatic rings.63 Moreover, the two distinctive bands of hydroxyl flavonoids at 1513 cm–1 and 1272 cm–1 would be related to the N–H bending vibration and C–O.63,64 In the polysaccharides’ spectra (Poly), the fingerprint bands for polysaccharides at 1399, 879, 1043, and 1083 cm–1 were clearly observed, which could be related to the C–H bending vibration, C–C stretching vibration, glycosidic, and C–O–H bonds, respectively. Furthermore, the presence of a band at 1594 cm–1 can be assigned to the COO– stretching vibration in galacturonic and glucuronic acid.65

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of (a) PVA, total ethanol extract, uncross-linked PVA/total ethanol extract, and cross-linked PVA/total ethanol extract NFs. (b) PVA, polysaccharides, uncross-linked PVA/polysaccharides, and cross-linked PVA/polysaccharides NFs.

In the FTIR spectra of the uncross-linked PVA/TEE L. sativum and PVA/poly NFs, a change in intensities, brooding, and shifting of the O–H stretching vibration band from 3297 and 3261 to 3333 and 3317 cm–1 was recorded, respectively. These noted changes could be explained as a result of the formation of intermolecular/intramolecular hydrogen bonds between PVA and the two types of L. sativum extracts. This observable brooding was consistent with a previously published work of doping PVA with the L. sativum extract.64 Previously, Fahami et al.59 reported that there was an occurrence of physical interaction among the components of L. sativum poly/PVA nanofiber, and there was no chemical interaction.59,61

Upon addition of citric acid as a cross-linker to PVA/TEE and PVA/Poly, a new band appears at 1721 and 1711 cm–1, respectively. These new bands were related to the C–O of the ester group. This band confirms a successful cross-linking reaction between the −COOH group of citric acid and the −OH of PVA.66 In further, CA might react with the −OH present in two L. sativum extracts.

ζ-Potential Measurements

ζ-Potential distribution values of the ethanol extract (TEE), Poly, and the prepared NFs are shown in Table 5. ζ-Potential measurements revealed the anionic nature of TEE and Poly, which indicated that the negative surface charges were −23.9 and −13.6 mV, respectively. This result was consistent with the previous estimated ζ-potential of biopolymers extracted from L. sativum, which was 16 mV.62 It was found that the ζ-potential values of PVA, PVA/TEE, and PVA/polys NFs were −0.62, −22.7, and −5.9 mV, respectively. It was clearly observed that PVA/TEE and PVA/poly NFs have more negative ζ-potential than PVA NFs alone. Such ζ-potential would produce the electrostatic repulsion force between similarly charged adjacent particles, which has an important role in the stability of the colloidal suspension of the prepared NFs by making the solution resistant to aggregation.67

Table 5. ζ-Potential Measurements of PVA, PVA/TEE, and PVA/Poly NFs.

| compound | TEE | polysaccharides | PVA NFs | PVA/TEE-NFs | PVA/Poly NFs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ζ-potential (mV) | –23.9 | –13.6 | –0.62 | –22.7 | –5.9 |

Physicochemical Characterization of PVA/TEE and PVA/Poly L. sativum Nanofibers

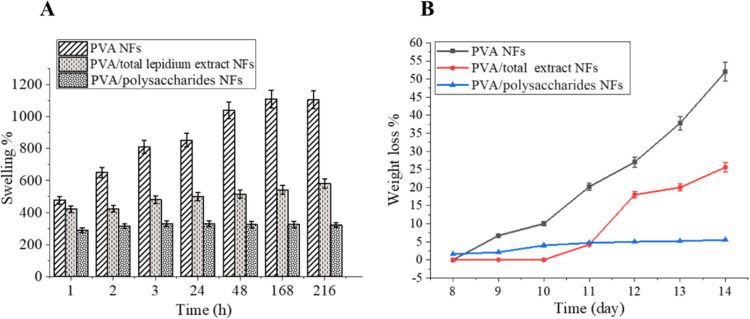

Swelling Study

Since the swelling behavior of dressings should be studied for investigating their ability to absorb wound exudates during the wound healing process, the swelling % values of three tested NFs are shown in Figure 3A. Generally, it was observed that the incorporation of the two extracts (TEE L. sativum and Poly) into PVA NFs decreased the swelling ratio, since the swelling ratio of PVA NFs, PVA/TEE L. sativum NFs, and PVA/Poly NFs recorded 477.6, 421.1, and 289.6% after 1 h of swelling. This reduction in swelling % could be due to the intramolecular hydrogen bond interaction between PVA and the two types of L. sativum extracts causing a decrease in the swelling capacity of the NFs.

Figure 3.

(A) Swelling of PVA, PVA/polysaccharide NFs, and PVA/total extract, (B) hydrolytic degradation of PVA, PVA/polysaccharide NFs, and PVA/total extract.

Meanwhile, the effect of polysaccharides incorporated on decreasing the swelling ratio was sharply compared to L. sativum TEE, owing to its constant slow swelling rate. This might be attributed to a high content of mucilaginous substance in L. sativum TEE that can absorb water and produce a large amount of hydrocolloids with high molecular weight.64 In addition, the CA cross-linker might increase the surface hydrophobicity by obstructing the hydrophilic hydroxyl groups of polysaccharides through the formation of a diester bond with the carboxylic groups of CA.68

From the swelling results, it was suggested that PVA/TEE L. sativum NFs could act as a suitable wound dressing scaffold since they have a proper swelling ratio that meets the requirements of wound healing, such as retaining wound exudates and nutrients, while PVA/polysaccharides NFs were not recommended owing to an inadequate and low swelling ratio that would result in insufficient nutrient supply to achieve the process of wound healing.69

Hydrolytic Degradation

Hydrolytic degradation of the tested nanofibers was performed as a function of weight loss (%) and evaluated by immersion of the three nanofibers for 14 days, as shown in Figure 3B. The results revealed that PVA NFs represent a higher hydrolytic degradation rate than other NFs, since there was about 52% of PVA NFs that were degraded after incubation for 14 days. However, PVA NFs had a constant degradation rate resulting from the secession of cross-linker segments that bind between the PVA chains, leading to degraded polymers with a low molecular weight.7

Conversely, as PVA/L. sativum TEE-NFs have a more stable hydrolytic degradation rate, they reach a hydrolytic degradation value of around ∼25% after 14 days of the incubation period. Meanwhile, PVA/polysaccharide NFs show resistance against hydrolytic degradation compared to other nanofibers as they reach hydrolytic degradation (∼5.5%) after 14 days of immersion time. This slowest hydrolytic degradation is probably owing to the high cross-linking density resulted from the formation of hydrogen and diester bonds.70,71

In Vitro Bio-Evaluation Tests

Cell Viability

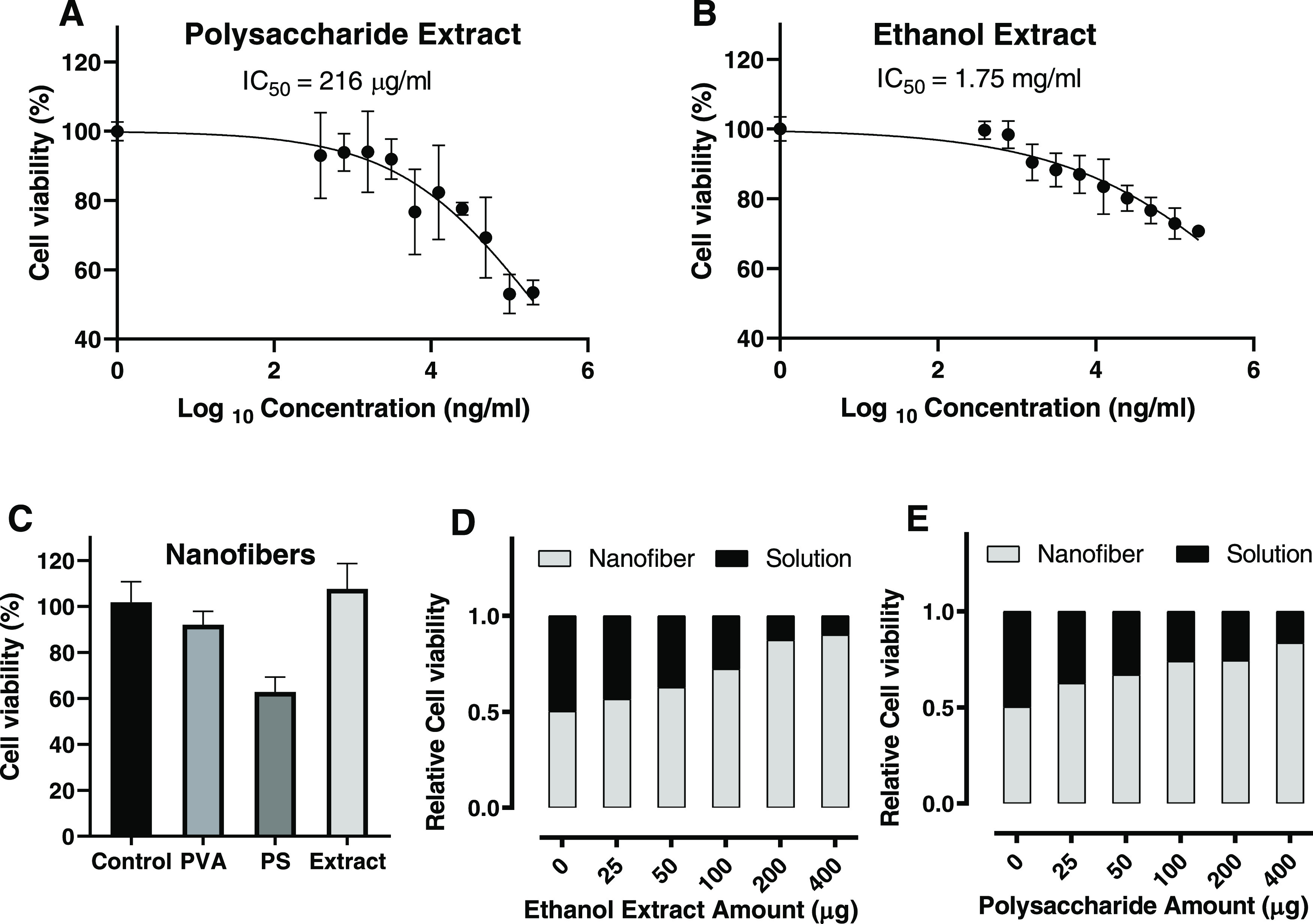

To investigate the cytotoxicity of the L. sativum total ethanol extract (TEE) and polysaccharide, the MTT colorimetric assay was performed on Vero fibroblast cell lines with different extract concentrations (200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, 0.78, and 0.39 μg/mL). After 48 h of incubation with the polysaccharide extract, the cells showed high viability, as 216 μg/mL of Poly extract kills less than 50% of the incubated cells compared to the control group (cells were treated with only culture medium; Figure 4A). However, there seemed to be a marked difference between the polysaccharides and the TEE of L. sativum in terms of cell viability, demonstrating an excellent and almost 8-fold efficacy to that of the ethanol extract with an IC50 value of 1.75 mg/mL. This marked difference between the polysaccharides and TEE may suggest that TEE was enriched with other important components that improved the cell viability (Figure 4B). The cytotoxicity of the prepared nanofibers was also analyzed by the MTT assay. The results supported the data obtained by MTT assay for the extracts in solution form. As shown in Figure 4C, the PVA nanofibers doped with TEE had a higher cell viability compared to the polysaccharides-doped and bare PVA nanofibers. The bare PVA showed a good cell viability of about 90% of the control. The result was expected since PVA is known to be nontoxic and biocompatible.9,72 It is also worth noting that the cell viability of the TEE-doped nanofibers was higher than that of the positive control, highlighting its potential as an anti-inflammatory agent.

Figure 4.

Cell viability with MTT assay for (A) polysaccharide extract as a solution, (B) ethanol (70%) extract as a solution, (C) nanofibers (PVA, PVA-polysaccharide extract, and PVA-ethanol (70%) extract), (D) ethanol extract in solution and nanofiber form, and (E) polysaccharide in solution and nanofiber form.

Another MTT test was conducted to compare the cell viability of extracts in solution and nanofiber forms. After calculating the quantity of the extract in each sample, the cells were incubated with the same amount of extracts and observed after 48 h. As shown in Figure 4D,E, the nanofibers possess higher cell viability compared to solutions with the same extract quantities. The ratio of cell viabilities between both forms increased as the quantity increased, highlighting the low exposure rate of materials from nanofibers, which was beneficial for safe and long-term treatment.

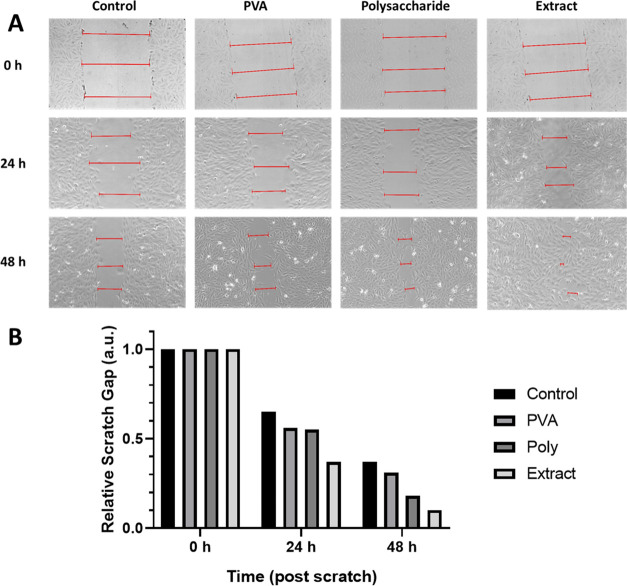

In Vitro Wound Healing

The scratch wound healing assay was performed to understand the effect of the prepared nanofibers in accelerating or decelerating the healing of wounds in vitro. The scratch assay results obtained from the images using the scratch test are given in Figure 5. After 24 h of treatment with the nanofibers, about 35% of the scratched area was healed in control (cells treated only with medium). A relatively higher trend was observed in the PVA and PVA-poly nanofibers, achieving about 45% wound closure. The incorporation of TEE in the nanofibers increased the gap closure efficiency and healing capability to about 63% in 24 h. After 48 h, the wound closure percent reached 63, 69, 82, and 90% for the control, bare PVA, PVA-polysaccharide, and PVA-total ethanol extract, respectively (Table 6). Overall, it had been observed that incorporating Poly and TEE into the nanofibers improved the cell migration for the in vitro wound model. However, TEE showed a higher healing capability compared to the polysaccharides. The results revealed their potential as anti-inflammatory agents for wound dressing.

Figure 5.

In vitro wound healing activity of nanofibers (bare PVA, PVA-polysaccharide and PVA-total ethanol extract; TEE) on Vero fibroblast cells: (A) bright-field images, (B) relative scratch gap after 0, 24, and 48 h of incubation.

Table 6. In Vitro Wound Healing Data Obtained by Analyzing the Bright-Field Images after 0, 24, and 48 h of Incubationa.

| width 1 (mm) | width 2 (mm) | width 3 (mm) | average width (mm) | wound closure % | relative scratch gap | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | control | 615 | 621 | 608 | 615 | 0 | 1.00 |

| PVA | 563 | 568 | 549 | 560 | 0 | 1.00 | |

| polysaccharide | 579 | 571 | 552 | 567 | 0 | 1.00 | |

| extract | 605 | 590 | 588 | 594 | 0 | 1.00 | |

| 24 h | control | 360 | 467 | 375 | 401 | 35 | 0.65 |

| PVA | 312 | 321 | 304 | 312 | 44 | 0.56 | |

| polysaccharide | 316 | 302 | 316 | 311 | 45 | 0.55 | |

| extract | 221 | 175 | 256 | 217 | 63 | 0.37 | |

| 48 h | control | 235 | 229 | 216 | 227 | 63 | 0.37 |

| PVA | 183 | 152 | 183 | 173 | 69 | 0.31 | |

| polysaccharide | 123 | 94 | 84 | 100 | 82 | 0.18 | |

| extract | 68 | 31 | 87 | 62 | 90 | 0.10 |

Extract = TEE.

Conclusions

L. sativum is a rich medicinal plant with phytoconstituents phenolic acids and flavonoids, which are responsible for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Owing to these activities, the total ethanol extract and polysaccharide show a promising wound-healing effect. Furthermore, total ethanol extract is more active due to their being enriched in phenolic acids and flavonoids, which show scavenging activity and accelerate the healing process. So, extracts derived from L. sativum seeds were suggested as an ideal candidate for nanofibrous wound dressings, which help in healing wounds after surgery or in diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

The experimental work was performed in the Pharmacognosy Department, Pharmaceutical and Drug Industries Research Institute, National Research Centre (NRC), with the scientific support of the British University in Egypt (BUE) in the nanofabrication work and wound-healing assay.

The authors declare that this work was done by the authors named in this article and all liabilities about claims relating to the content of this article will be borne by them.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Voss M.; Kotrba J.; Gaffal E.; Katsoulis-Dimitriou K.; Dudeck A. Mast Cells in the Skin: Defenders of Integrity or Offenders in Inflammation?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4589 10.3390/ijms22094589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado C.; Mercado-Saenz S.; Perez-Davo A.; Gilaberte Y.; Gonzalez S.; Juarranz A. Environmental Stressors on Skin Aging. Mechanistic Insights. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 759 10.3389/fphar.2019.00759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottoli E. M.; Dorati R.; Genta I.; Chiesa E.; Pisani S.; Conti B. Skin Wound Healing Process and New Emerging Technologies for Skin Wound Care and Regeneration. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 735 10.3390/pharmaceutics12080735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalva S. N.; Augustine R.; Al Mamun A.; Dalvi Y. B.; Vijay N.; Hasan A. Active Agents Loaded Extracellular Matrix Mimetic Electrospun Membranes for Wound Healing Applications. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 102500 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Ronca S.; Mele E. Electrospun Nanofibres Containing Antimicrobial Plant Extracts. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 42 10.3390/nano7020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacakova L.; Zikmundova M.; Pajorova J.; Broz A.; Filova E.; Blanquer A.; Matejka R.; Stepanovska J.; Mikes P.; Jencova V.; Kuzelova Kostakova E.; Sinica A. Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Skin Tissue Engineering and Wound Healing Based on Synthetic Polymers. Appl. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 33–61. 10.5772/intechopen.88744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy A.; Kamoun E. A.; El-Eisawy R.; El-Fakharany E. M.; Taha T. H.; El-Damhougy B. K.; Abdelhai F. Poly (Vinyl Alcohol)-Hyaluronic Acid Membranes for Wound Dressing Applications: Synthesis and in Vitro Bio-Evaluations. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2015, 26, 1466–1474. 10.5935/0103-5053.20150115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fatehi P.; Abbasi M. Medicinal Plants Used in Wound Dressings Made of Electrospun Nanofibers. J. Tissue Eng. Regener. Med. 2020, 14, 1527–1548. 10.1002/term.3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Han S. S. PVA-Based Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering: A Review. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2017, 66, 159–182. 10.1080/00914037.2016.1190930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S.; Singhal R. S.; Kulkarni P. R. Some Physicochemical Characteristics of Lepidium sativum (Haliv) Seeds. Food 1993, 37, 69–71. 10.1002/food.19930370113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gokavi S. S.; Malleshi N. G.; Guo M. Chemical Composition of Garden Cress (Lepidium sativum) Seeds and Its Fractions and Use of Bran as a Functional Ingredient. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2004, 59, 105–111. 10.1007/s11130-004-4308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiyrkulova A.; Li J.; Aisa H. A. Chemical Constituents of Lepidium sativum Seeds. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2019, 55, 736–737. 10.1007/s10600-019-02795-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.; Agarwal N. Nourishing and Healing Prowess of Garden Cress (Lepidium sativum Linn.)-A Review. J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2011, 2, 292–297. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan C.; Rama Sastri B. V.; Balasubramanian S. C.. et al. Nutritive Value of Indian Foods; National Institute of Nutrition: Hyderabad, India, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Jain T.; Grover K. Nutritional Evaluation of Garden Cress Chikki. Agric. Res. Technol. Open Access J. 2017, 4, 555–631. 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2017.04.555631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigoniya P.; Shukla A. Phytopharmacological Screening of Lepidium sativum Seeds Total Alkaloid: Hepatoprotective, Antidiabetic and in Vitro Antioxidant Activity along with Identification by LC/MS/MS. PharmaNutrition 2014, 2, 90 10.1016/j.phanu.2013.11.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit JR V. III; Kumar I.; Palandurkar K.; Giri R.; Giri K. Lepidium sativum: Bone Healer in Traditional Medicine, an Experimental Validation Study in Rats. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 812 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_761_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw R. A.; Percival E. G. V. 345. Studies on Seed Mucilages. Part III. Examination of a Polysaccharide Extracted from the Seeds of Plantago Ovata Forsk. J. Chem. Soc. 1949, 1600–1607. 10.1039/jr9490001600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlassare M. [The National Formulary, supplement of the French pharmacopoeia]. Boll. Chim. Farm. 1975, 114, 375–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh J.; Chanda S. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Phytochemical Analysis of Some Indian Medicinal Plants. Turkish J. Biol. 2007, 31, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu K.; Karar P. K.; Hemalatha S.; Ponnudurai K.; et al. A Comparative Preliminary Phytochemical Screening on the Leaves, Stems and the Roots of Three Viburnum Linn. Species. Der Pharm. Sin. 2011, 2, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde P. R.; Patil P. S.; Bairagi V. A. Pharmacognostic, Phytochemical Properties and Antibacterial Activity of Callistemon Citrinus Viminalis Leaves and Stems. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 4, 406–408. [Google Scholar]

- Attard E. A Rapid Microtitre Plate Folin-Ciocalteu Method for the Assessment of Polyphenols. Open Life Sci. 2013, 8, 48–53. 10.2478/s11535-012-0107-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal P. K.; Thakur R. S.; Bansal M. C.;et al. Flavonoids. In Carbon-13 NMR Flavonoids; Springer, 1989; Vol. 564. [Google Scholar]

- Markham K. R.; et al. Techniques of Flavonoid Identification; Academic Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mabry T.; Markham K. R.; Thomas M. B.. The Systematic Identification of Flavonoids; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Churms S. C.; Stephen A. The Determination of Molecular-Weight Distributions of Maize Starch Dextrins by Gel Chromatography. S. Afr. J. Chem. 1971, 24, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk R. S.; Sawer R.. Pearson’s Composition and Analysis of Food; Longman Scientific and Technical. Inc.: New York: 1991; pp 469–529. [Google Scholar]

- Boly R.; Lamkami T.; Lompo M.; Dubois J.; Guissou I. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Two Extracts from Agelanthus Dodoneifolius (Loranthaceae) Leaves. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Raslan M. A.; Afifi A. H. In Vitro Wound Healing Properties, Antioxidant Activities, HPLC-ESI-MS/MS Profile and Phytoconstituents of the Stem Aqueous Methanolic Extract of Dracaena Reflexa Lam. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2022, 36, e5352 10.1002/bmc.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzie I. F. F.; Strain J. J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnao M. B.; Cano A.; Acosta M. The Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Contribution to Total Antioxidant Activity. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 239–244. 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00324-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Bertin R.; Froldi G. EC50 Estimation of Antioxidant Activity in DPPH Assay Using Several Statistical Programs. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 414–420. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi Dehkordi N.; Minaiyan M.; Talebi A.; Akbari V.; Taheri A. Nanocrystalline Cellulose--Hyaluronic Acid Composite Enriched with GM-CSF Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for Enhanced Wound Healing. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 14, 035003 10.1088/1748-605X/ab026c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadisi Z.; Farokhi M.; Bakhsheshi-Rad H. R.; Jahanshahi M.; Hasanpour S.; Pagan E.; Dolatshahi-Pirouz A.; Zhang Y. S.; Kundu S. C.; Akbari M. Hyaluronic Acid (HA)-Based Silk Fibroin/Zinc Oxide Core--Shell Electrospun Dressing for Burn Wound Management. Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, 1900328 10.1002/mabi.201900328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein Y.; El-Fakharany E. M.; Kamoun E. A.; Loutfy S. A.; Amin R.; Taha T. H.; Salim S. A.; Amer M. Electrospun PVA/Hyaluronic Acid/L-Arginine Nanofibers for Wound Healing Applications: Nanofibers Optimization and in Vitro Bioevaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 667–676. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghante M. H.; Badole S. L.; Bodhankar S. L.. Health Benefits of Garden Cress (Lepidium sativum Linn.) Seed Extracts. In Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier, 2011; pp 521–525. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R. K.; Vyas K.; Manda H. Evaluation of Antifungal Effect on Ethanolic Extract of Lepidium sativum L. Seeds. Int. J. Phytopharm. 2012, 3, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav Y. C.; Jain A.; Srivastava D. N.; Jain A. Fracture Healing Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Lepidium sativum L. Seeds in Internally Fixed Rats’ Femoral Osteotomy Model. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 3, 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chatoui K.; Harhar H.; El Kamli T.; Tabyaoui M. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of Lepidium sativum Seeds from Four Regions of Morocco. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 7302727 10.1155/2020/7302727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Yahia O.; Perreau F.; Bouzroura S. A.; Benmalek Y.; Dob T.; Belkebir A. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of N-Butanol Extract of Lepidium sativum L (Brassicaceae) Seed. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 891–896. 10.4314/tjpr.v17i5.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Salam K.; Kholoud H.; Toliba A. O.; El-Shourbagy G. A.; El-Nemr S. E. Chemical and Functional Properties of Garden Cress (Lepidium sativum L.) Seeds Powder. Zagazig J. Agric. Res. 2019, 46, 1517–1528. 10.21608/zjar.2019.48168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panwar H.; Guha M. Effect of Processing on Nutraceutical Properties of Garden Cress (Lepidium sativum L.) Seeds. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Yahia O.; Perreau F.; Bouzroura S. A.; Benmalek Y.; Dob T.; Belkebir A. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of N-Butanol Extract of Lepidium sativum L (Brassicaceae) Seed. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 17, 891–896. 10.4314/tjpr.v17i5.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabort D.; Sunanda C.; et al. Bioassay-Guided Isolation and Identification of Antibacterial and Antifungal Component from Methanolic Extract of Green Tea Leaves (Camellia Sinensis). Res. J. Phytochem. 2010, 4, 78–86. 10.3923/rjphyto.2010.78.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hye M. A.; Taher M. A.; Ali M. Y.; Ali M. U.; Zaman S. Isolation of (+)-Catechin from Acacia Catechu (Cutch Tree) by a Convenient Method. J. Sci. Res. 2009, 1, 300–305. 10.3329/jsr.v1i2.1635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Aziz M.; Haggag H. F.; Kaluoubi M. M.; Hassan L. K.; El-Sayed M. M.; Sayed A. F. Evaluation of Hypolipedimic Activity of Ethanol Precipitated Cress Seed and Flaxseed Mucilage in Wister Albino Rats. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 606–613. [Google Scholar]

- Behrouzian F.; Razavi S. M. A.; Karazhiyan H. Intrinsic Viscosity of Cress (Lepidium sativum) Seed Gum: Effect of Salts and Sugars. Food Hydrocolloids 2014, 35, 100–105. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakasha G. K.; Singh R. P.; Sakariah K. K. Antioxidant Activity of Grape Seed (Vitis Vinifera) Extracts on Peroxidation Models in Vitro. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 285–290. 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00298-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwin S.; Jarald E. E.; Deb L.; Jain A.; Kinger H.; Dutt K. R.; Raj A. A. Wound Healing and Antioxidant Activity of Achyranthes Aspera. Pharm. Biol. 2008, 46, 824–828. 10.1080/13880200802366645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton P. J.; Hylands P. J.; Mensah A. Y.; Hensel A.; Deters A. M. In Vitro Tests and Ethnopharmacological Investigations: Wound Healing as an Example. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 100–107. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M.; Govindarajan R.; Nath V.; Rawat A. K. S.; Mehrotra S. Antimicrobial, Wound Healing and Antioxidant Activity of Plagiochasma Appendiculatum Lehm. et Lind. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107, 67–72. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geethalakshmi R.; Sakravarthi C.; Kritika T.; Arul Kirubakaran M.; Sarada D. V. L. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Wound Healing Potentials of Sphaeranthus Amaranthoides Burm. F. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 607109 10.1155/2013/607109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel E. N.; Meyer A. S. The Problems of Using One-Dimensional Methods to Evaluate Multifunctional Food and Biological Antioxidants. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1925–1941. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.; Ou B.; Prior R. L. The Chemistry behind Antioxidant Capacity Assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. 10.1021/jf030723c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubina V. S.; Kozina V. I.; Shatalin Y. V. Comparison of Antioxidant Properties of a Conjugate of Taxifolin with Glyoxylic Acid and Selected Flavonoids. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1262 10.3390/antiox10081262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Fawal G. F. Polymer Nanofibers Electrospinning: A Review. Egypt. J. Chem. 2020, 63, 1279–1303. 10.21608/ejchem.2019.14837.1898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fahami A.; Fathi M. Fabrication and Characterization of Novel Nanofibers from Cress Seed Mucilage for Food Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45811 10.1002/app.45811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haider A.; Haider S.; Kang I.-K. A Comprehensive Review Summarizing the Effect of Electrospinning Parameters and Potential Applications of Nanofibers in Biomedical and Biotechnology. Arab. J. Chem. 2018, 11, 1165–1188. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fahami A.; Fathi M. Development of Cress Seed Mucilage/PVA Nanofibers as a Novel Carrier for Vitamin A Delivery. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 81, 31–38. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim B.-C.; Lim J.-W.; Ho Y.-C. Garden Cress Mucilage as a Potential Emerging Biopolymer for Improving Turbidity Removal in Water Treatment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 119, 233–241. 10.1016/j.psep.2018.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira R. N.; Mancini M. C.; de Oliveira F. C. S.; Passos T. M.; Quilty B.; Thiré R. M. d. S. M.; McGuinness G. B. FTIR Analysis and Quantification of Phenols and Flavonoids of Five Commercially Available Plants Extracts Used in Wound Healing. Matéria 2016, 21, 767–779. 10.1590/S1517-707620160003.0072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelghany A. M.; Meikhail M. S.; Abdelraheem G. E. A.; Badr S. I.; Elsheshtawy N. Lepidium sativum Natural Seed Plant Extract in the Structural and Physical Characteristics of Polyvinyl Alcohol. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 75, 965–977. 10.1080/00207233.2018.1479564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karazhiyan H.; Razavi S. M. A.; Phillips G. O.; Fang Y.; Al-Assaf S.; Nishinari K. Physicochemical Aspects of Hydrocolloid Extract from the Seeds of Lepidium sativum. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1066–1072. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02583.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Sun Q.; Li Q.; Kawazoe N.; Chen G. Functional Hydrogels with Tunable Structures and Properties for Tissue Engineering Applications. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 499 10.3389/fchem.2018.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignesh R. M.; Nair B. R. Extraction and Characterisation of Mucilage from the Leaves of Hibiscus Rosa-Sinensis Linn.(MALVACEAE). Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2018, 6, 542–555. [Google Scholar]

- Wilpiszewska K.; Antosik A. K.; Zdanowicz M. The Effect of Citric Acid on Physicochemical Properties of Hydrophilic Carboxymethyl Starch-Based Films. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 1379–1387. 10.1007/s10924-019-01436-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.-f.; Liu N.; Sun H.; Xu F. Preparation and Characterization of Electrospun PLCL/Poloxamer Nanofibers and Dextran/Gelatin Hydrogels for Skin Tissue Engineering. PLoS One 2014, 9, e112885 10.1371/journal.pone.0112885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goreninskii S. I.; Bolbasov E. N.; Sudarev E. A.; Stankevich K. S.; Anissimov Y. G.; Golovkin A. S.; Mishanin A. I.; Viknianshchuk A. N.; Filimonov V. D.; Tverdokhlebov S. I. Fabrication and Properties of L-Arginine-Doped PCL Electrospun Composite Scaffolds. Mater. Lett. 2018, 214, 64–67. 10.1016/j.matlet.2017.11.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udhayakumar S.; Shankar K. G.; Sowndarya S.; Venkatesh S.; Muralidharan C.; Rose C. L-Arginine Intercedes Bio-Crosslinking of a Collagen--Chitosan 3D-Hybrid Scaffold for Tissue Engineering and Regeneration: In Silico, in Vitro, and in Vivo Studies. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 25070–25088. 10.1039/C7RA02842C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre N.; Ribeiro J.; Gärtner A.; Pereira T.; Amorim I.; Fragoso J.; Lopes A.; Fernandes J.; Costa E.; Santos-Silva A.; et al. Biocompatibility and Hemocompatibility of Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogel Used for Vascular Grafting—In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2014, 102, 4262–4275. 10.1002/jbm.a.35098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]