Abstract

Rhomboid-like proteins are intramembrane proteases with a variety of regulatory roles in cells. Though many rhomboid-like proteins are predicted in plants, their detailed molecular mechanisms or cellular functions are not yet known. Of the 13 predicted rhomboids in Arabidopsis thaliana, one, RBL10, affects lipid metabolism in the chloroplast, because in the respective rbl10 mutant the transfer of phosphatidic acid through the inner envelope membrane is disrupted. Here we show that RBL10 is part of a large molecular weight complex of 250 kDa or greater in size. Nine likely components of this complex are identified by two independent methods and include Acyl Carrier Protein 4 (ACP4) and Carboxyltransferase Interactor1 (CTI1), which have known roles in chloroplast lipid metabolism. The acp4 mutant has a decrease in C16:3 fatty acid content of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol similar to the rbl10 mutant prompting us to offer a mechanistic model how an interaction between ACP4 and RBL10 might affect chloroplast lipid assembly. We also demonstrate the presence of a seventh transmembrane domain in RBL10, refining the currently accepted topology of this protein. Taken together, the identity of possible RBL10 complex components as well as insights into RBL10 topology and distribution in the membrane provide a stepping-stone towards a deeper understanding of RBL10 function in Arabidopsis lipid metabolism.

Keywords: plant biochemistry, lipid trafficking, membrane biogenesis, rhomboid protease, acyl carrier protein (ACP)

Introduction

Rhomboid family proteins carry out intramembrane proteolysis, utilizing a serine and histidine catalytic dyad to process peptides within the lipid bilayer of the membrane (Cho et al. 2019). Their roles vary depending on the organelle they associate with and the tissues they are present in. Generally, members of the rhomboid family tend to carry out regulated intramembrane proteolysis, releasing receptor peptide ligands (Lee et al. 2001, Urban et al. 2002), initiating peptide trafficking (Meissner et al. 2011), and enabling the oligomerization of complexes (Stevenson et al. 2007). Rhomboids maintain selectivity for transmembrane helices while scanning the membrane for their substrates, rather than recognizing an amino acid consensus sequence (Kreutzberger et al. 2019, Moin and Urban 2012). Rhomboid proteases and their regulatory roles have gained medical relevance since the discovery of the family in Drosophila melanogaster (Bergbold and Lemberg 2013, Freeman 2016). While an appreciable number of rhomboid roles have been described so far, no rhomboids have been fully functionally characterized in plants even though many members have been predicted in Arabidopsis thaliana, Populus trichocarpa, and Oryza sativa (Garcia-Lorenzo et al. 2006, Lemberg and Freeman 2007, Tripathi and Sowdhamini 2006). An active member of the rhomboid family has been confirmed with protease activity assays in Arabidopsis (Kanaoka et al. 2005) though its biological role remains elusive. So far, the most-studied plant rhomboid is found in the chloroplasts of Arabidopsis and is encoded by At1g25290 or RHOMBOID-LIKE PROTEIN 10 (RBL10). A number of publications probed the biological relevance of RBL10 as well as its mechanism, showing that loss-of-function of RBL10 causes altered pollen morphology and floral defects, and possibly affects jasmonic acid (JA) signaling (Knopf et al. 2012, Thompson et al. 2012). More recently, RBL10 has been implicated in Arabidopsis lipid metabolism and the utilization of chloroplast assembled phosphatidic acid (PA) for galactolipid biosynthesis (Lavell et al. 2019). Though the involvement of RBL10 in lipid metabolism narrowed its potential biological function, the exact mechanism through which this rhomboid-like protein affects PA metabolism or transport is not clear. Here we describe protein interactors of RBL10 and refine its membrane topology. A possible functional relevance of two molecular interactors of RBL10 involved in lipid metabolism is further explored.

Results

RBL10 is a component of a large protein complex

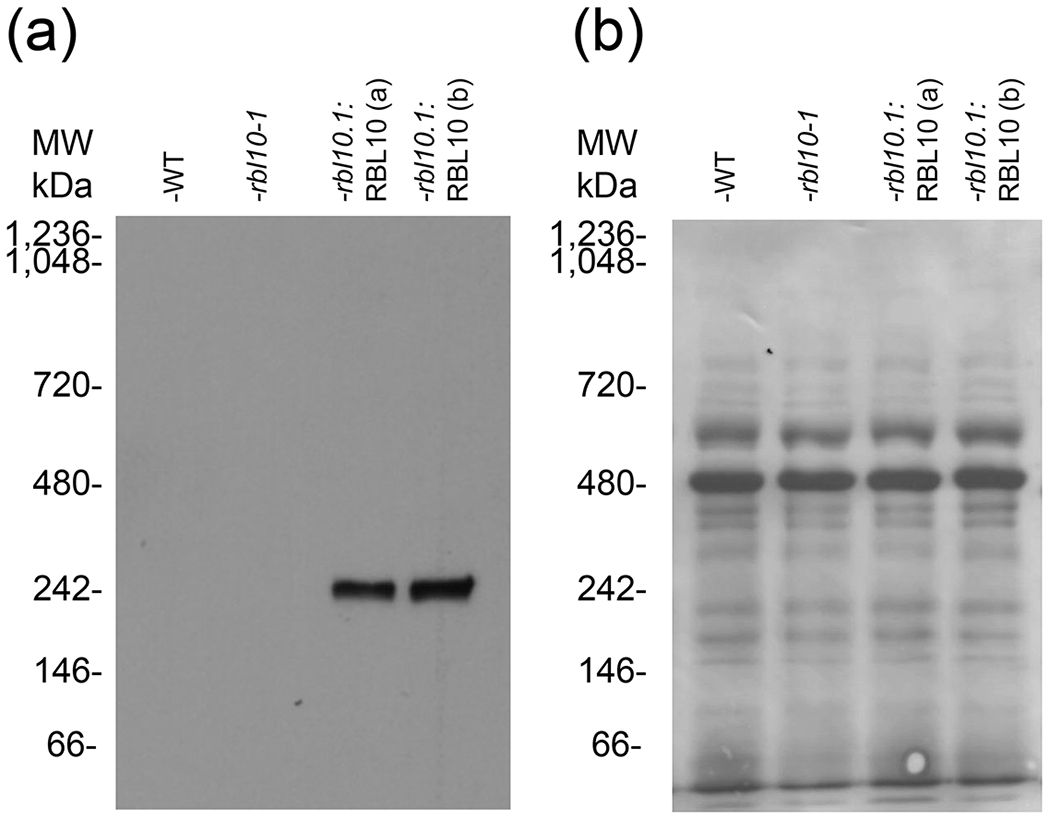

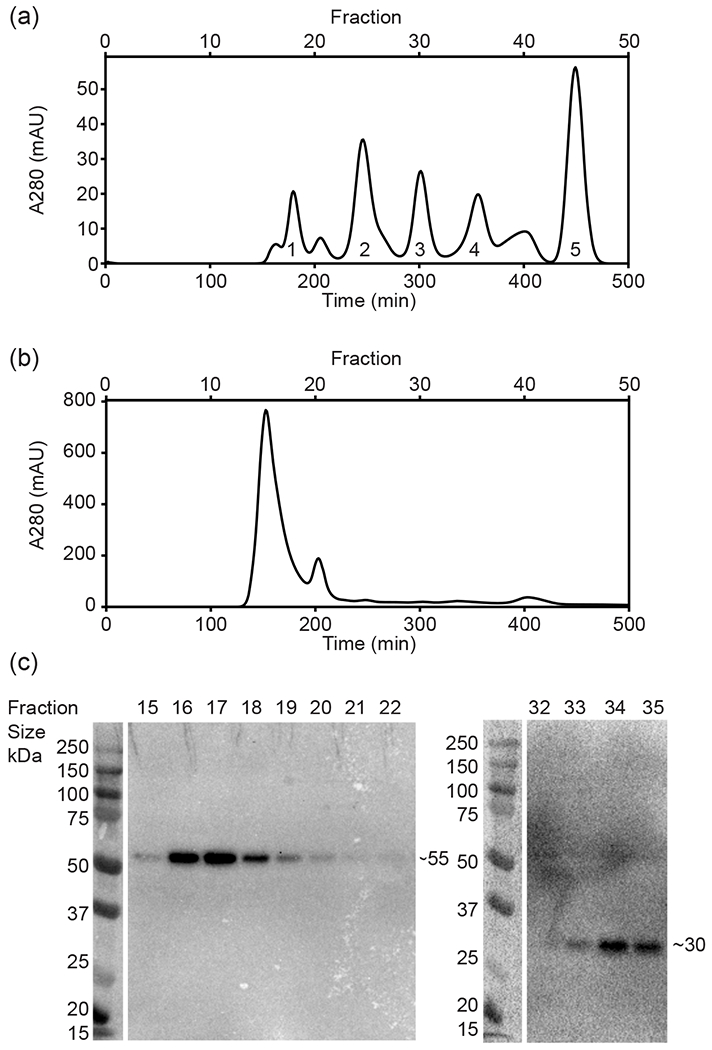

An outstanding question surrounding rhomboid catalysis concerns the oligomeric state of rhomboids and the hypothesis that they primarily exist as obligate monomers. There are known rhomboid protein non-substrate interactors (Jeyaraju et al. 2006), although few examples of stable complexes involving rhomboids have been reported (Knopf et al. 2012). Upon immunoblotting of potential RBL10-YFP-HA complexes from transgenic Arabidopsis plants, which were analyzed by separating solubilized chloroplast proteins under non-denaturing conditions using Blue-Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE), it appears that RBL10 may be a component of a large molecular weight complex (Fig. 1). Probing for the HA-tag, a strong signal was observed representing an RBL10-YFP-HA containing complex with a molecular weight close to the 250 kDa. The observed size is much larger than expected for a monomer or even dimer of the tagged and mature protein (~55 and ~110kDa respectively). Large RBL10 containing protein complexes were corroborated by size exclusion chromatography, where solubilized chloroplast proteins of RBL10-YFP-HA-expressing Arabidopsis were separated on a Superdex 200 column (Fig. 2). A set of protein standards ranging from 0.137 to 660 kDa was used (Fig. 2a) to estimate the size of large MW chloroplast complexes (Fig. 2b). With larger MW proteins and complexes eluting earlier, we readily observed through immunoblotting the elution of the full-length RBL10-YFP-HA fusion protein in the earlier fractions (fractions 15-22 Fig. 2c) corresponding to a MW of >660 kDa. Since we primarily saw the elution of the intact fusion protein earlier than expected for complexes smaller than 660kDa, it is likely that the smaller complex of approximately 250 kDa observed by BN-PAGE was due to the partial dissociation of the RBL10 complex under the harsher condition of electrophoresis, leaving only a more robust core complex behind. We also observed a smaller fragment which elutes in later fractions and can be detected by anti-HA antibody and is just larger than 30 kDa in size (fractions 32-35 Fig. 2c). This is too small to be a monomer of RBL10-YFP-HA (~55 kDa) but slightly larger than YFP-HA alone (27.5 KDa). We suspected that this fragment was a product of RBL10 proteolytic processing. Both methods, BN-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography suggested that RBL10 is a component of (a) larger protein complex(es) that prompted our search for protein interactors of RBL10.

Figure 1. Blue Native PAGE of solubilized chloroplasts from wild type (WT), rbl10-1 mutant, and rbl10-1 complemented lines producing RBL10-YFP-HA protein.

(a) Immunoblotting of a BN-PAGE gel transfer, detecting HA tag, shows only a signal in the complemented line with a band of approximately 250 kDa in size. (b) The immunoblot in (a) stained with Coomassie blue is showing the transferred proteins. Two chloroplast preparations from different sets of transgenic plants rbl10-1: RBL10 (a) and rbl10-1: RBL10 (b) are shown.

Figure 2. Size Exclusion Chromatography of protein standards and solubilized chloroplasts of the rbl10-1:RBL10-YFP-HA line show that RBL10 migrates in a complex at a high MW.

(a) The standard compounds used were: 1, Thyroglobulin (660 kDa); 2, Bovine γ-globulins (150 kDa); 3, Chicken albumin (44.3 kDa); 4, Ribonuclease A type I-A (13.7 kDa); 5, P-aminobenzoic acid (pABA)(137Da). They are resolved on a Superdex 200 column with A280 monitoring of protein elution over time. (b) Elution of solubilized chloroplast proteins isolated from the rbl10-1:RBL10-YFP-HA line after separation on the Superdex 200 column, monitored with A280 over time. (c) SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis showing fractions containing separated chloroplast proteins from (b), with detected HA tag indicative of the presence of RBL10-YFP-HA protein.

Co-Immunoprecipitation of RBL10 Yields Putative Protein Interactors

To identify possible protein interactors and substrates of RBL10, we used a co-immunoprecipitation approach based on evidence that the RBL10-YFP-HA fusion protein is found in a complex in planta (see Figs 1 and 2). Therefore, potentially interacting proteins present in chloroplast extracts from transgenic plants expressing the RBL10-YFP-HA construct in the rbl10-1 mutant background were bound to magnetic beads with an antibody specific for the HA-tag present on RBL10-YFP-HA. To control for non-specific binding, an isotype control antibody was used, which has no specificity toward HA or other proteins present in the chloroplast lysate. Both samples were submitted for mass spectrometry and a few hundred proteins were detected in both sample sets. However, upon comparing the HA-specific and control samples across three experimental replicates, a small subset of proteins was identified repeatedly specific to the HA-specific sample (Table 1). Twenty-two proteins co-immunoprecipitated with RBL10-YFP-HA in at least two of the three replicates. Of those 22, a single protein (#15) appeared in all three experimental replicates, annotated as ribosomal protein S1 (RPS1) with gene ID At5g30510 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proteins coimmunoprecipitated with RBL10-YFP-HA from chloroplast lysate (n=3).*

| # | Gene Annotation | Accession Number | MW kDa | Net Enrichment | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PGK1 - phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | AT3G12780 | 50 | 10.483 | 2 |

| 2 | ATPC1 - ATPase, F1 complex, gamma subunit protein | AT4G04640 | 41 | 4.765 | 2 |

| 3 | Transketolase | AT3G60750 | 80 | 4.765 | 2 |

| 4 | LHCB3 - light-harvesting chlorophyll B-binding protein 3 | AT5G54270 | 29 | 4.765 | 2 |

| 5 | PSB27 - photosystem II family protein | AT1G03600 | 19 | 3.7131 | 2 |

| 6 | ATPase, F0 complex, subunit B/B’, bacterial/chloroplast | AT4G32260 | 24 | 2.6612 | 2 |

| 7 | ZKT - protein containing PDZ domain, a K-box domain, and a TPR region | AT1G55480 | 37 | 2.859 | 2 |

| 8 | APX4 - ascorbate peroxidase 4 | AT4G09010 | 38 | 1.8071 | 2 |

| 9 | TOC159 - translocon at the OEM of chloroplasts 159 |

AT4G02510 | 161 | 1.9833 | 2 |

| 10 | CPN60B, LEN1 - chaperonin 60 beta | AT1G55490 | 64 | 1.906 | 2 |

| 11 | EDA9 - D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | AT4G34200 | 63 | 1.906 | 2 |

| 12 | SBPASE - sedoheptulose-bisphosphatase | AT3G55800 | 42 | 1.906 | 2 |

| 13 | CLPC1 - CLPC homologue 1 | AT5G50920 | 103 | 1.906 | 2 |

| 14 | ATPB - ATP synthase subunit beta | ATCG00480 | 54 | 0.99167 | 2 |

| 15 | RPS1 - ribosomal protein S1 | AT5G30510 | 45 | 0.99167 | 3 |

| 16 | RPL2.1 - ribosomal protein L2 | ATCG00830 | 30 | 0.99167 | 2 |

| 17 | Pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxidoreductase family protein | AT1G74470 | 52 | 0.99167 | 2 |

| 18 | Thioredoxin superfamily protein | AT3G11630 | 29 | 0.95299 | 2 |

| 19 | PRK - phosphoribulokinase | AT1G32060 | 44 | 0.95299 | 2 |

| 20 | FTSH1 - FTSH protease 1 | AT1G50250 | 77 | 0.95299 | 2 |

| 21 | ACP4 - acyl carrier protein 4 | AT4G25050 | 15 | 0.95299 | 2 |

| 22 | CPN20 - chaperonin 20 | AT5G20720 | 27 | 0.95299 | 2 |

Proteins that were identified as at least twice as abundant in the anti-HA sample versus control are described here with their gene annotation, their gene ID, predicted molecular mass, the enrichment in the anti-HA sample compared to the control, and the recurrence out of three experimental replicates. Net enrichment = (normalized total peptide spectra in anti-HA sample – normalized total peptide spectra in control sample) / normalized total peptide spectra in control sample.

The remaining 21 proteins which appeared in two of three replicates have annotations related to processes such as photosynthesis, protein import, chaperonin function, carbohydrate metabolism, signaling, as well as one protein possibly related to fatty acid metabolism (Table 1). Three additional proteins encoded by At1g42960, At3g08920, and At5g19940 only appeared in one of three replicates but were included in the subsequent analyses due to the presence of transmembrane helices typical for rhomboid substrates because of a possible function in lipid metabolism.

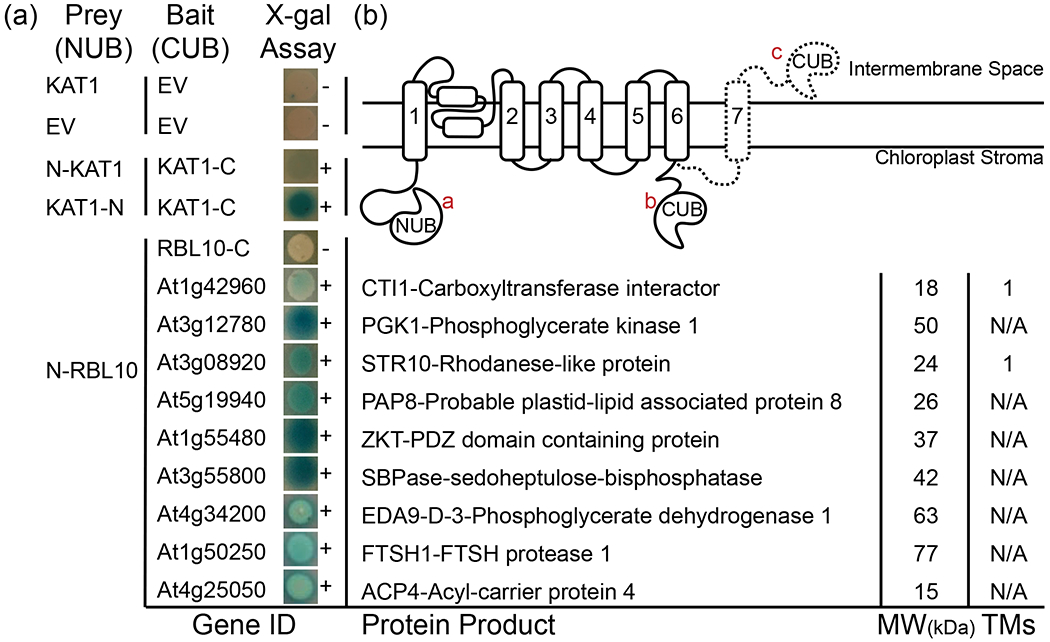

Split-Ubiquitin Assays Identify Nine Potential Interactors of RBL10

To test by an alternative method whether the above identified proteins indeed interact with RBL10, a membrane optimized split ubiquitin yeast two-hybrid approach was used. Following (Obrdlik et al. 2004), candidates from the list, including RBL10 itself, were tested for interaction with RBL10 through growth and β-galactosidase activity assays. Primer sequences for successfully amplified candidates can be found in Table S1. Transit peptides were removed to avoid potential targeting to yeast mitochondria. Using this approach, nine proteins were validated to interact with RBL10 (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Split-ubiquitin assay suggests chloroplast proteins interact with RBL10.

(a) No interaction demonstrated by KAT1 in NUB vector and empty CUB vector as well as both empty vectors (no blue in X-gal assay and [−]). Positive interaction demonstrated by mating yeast bearing N-terminally labeled KAT1 and C-terminally labeled KAT1 in the NUB vector with KAT1 in the CUB vector (shown with blue in the X-gal assay and [+]). Interaction with N-terminally labeled RBL10 in the NUB vector and 9 other candidates but not itself in the CUB vector. Details of the protein product of each gene shown to interact with RBL10 including known name, molecular weight in kDa, and number of probable transmembrane spanning domains. (b) Representation of possible RBL10 topology, showing the relationship between the amino-terminal half of the ubiquitin molecule on the amino-terminal end of RBL10 a, the carboxy-terminal half of the ubiquitin molecule on the carboxy-terminal end of RBL10 with only six transmembrane segments predicted b and with predicted seventh transmembrane domain c indicating separation between the amino and carboxy-terminal ends of RBL10 on the two different sides of the membrane.

Of the identified interactors of RBL10, Acyl-Carrier Protein 4 (ACP4) encoded by At4g25050, links back to lipid metabolism in the plastid. Among several Arabidopsis ACPs (Battey and Ohlrogge 1990), ACP4 is specifically present in leaf tissue and the expression of the respective gene appears to be light responsive (Bonaventure and Ohlrogge 2002). Additionally, potential interactors encoded by At1g42960 (CTI1-Carboxyltransferase Interactor1), At3g08920 (STR10-Rhodanese-like protein), and At5g19940 (PAP8-Probable Plastid-Lipid Associated Protein or FBN6), which were only identified in single replicates of the Co-IP analysis, appear to interact with RBL10 in the split ubiquitin yeast two-hybrid assay (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, CTI, a small plastid protein of the envelope membrane, was recently described as an interactor of the α-carboxyltransferase subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) (Ye et al. 2020), which catalyzes the first committed step of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis in plants. The interaction of CTI1 with ACCase was found to mediate its docking to the plastid envelope membrane, thereby attenuating fatty acid biosynthesis (Ye, et al. 2020). The identified interaction between RBL10 and CTI1 might play a role in retaining CTI1 in the envelope membrane, since the abundance of CTI1 is up to 50% reduced in the envelope membrane of the rbl10, rbl11 double mutant line (Knopf et al. 2012), taking into account that RBL11 has no known function in lipid metabolism (Lavell, et al. 2019).

Another protein that appeared to interact with RBL10 was ZKT (MET1) encoded by At1g55480. It is a plastid protein that associates primarily with membranes including the thylakoids and contains TPR, PDZ, and K-box region domains (Bhuiyan et al. 2015, Ishikawa et al. 2005). PDZ domains are present throughout eukaryotic protein sequences and confer protein-protein and protein-lipid binding properties (Jelen et al. 2003).

Two surprising interactors represent Calvin-Benson cycle enzymes and are encoded by At3g12780 (Phosphoglycerate Kinase 1 – PGK1) and At3g55800 (Sedoheptulose1,7-Bisphosphatase – SBPase) (Fig. 3). While several PGKs are present in Arabidopsis and are functionally redundant, PGK1 is found only in the plastids of photosynthetic tissues. In the Calvin-Benson cycle it catalyzes the addition of phosphate from ATP to 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA), generating 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3-BPG) and ADP (Rosa-Tellez et al. 2018). An interactor of RBL10 that appears to influence growth and development is D-3-Phoshpoglycerate dehydrogenase 1 (PGDH1 or EDA9) encoded by At4g34200. PGDH1 catalyzes the first committed step of serine biosynthesis and out of three PGDH-encoding genes in Arabidopsis, this appears to be essential and induced under salt stress (Rosa-Tellez et al. 2020, Toujani et al. 2013).

An additional finding was that RBL10 interactors were observed only with the split ubiquitin attached to the amino-terminal (NTD) end of RBL10 but not to the carboxy-terminal (CTD) end. The identified RBL10 interactors were detected both for wild-type RBL10 (Fig. S1a) and the catalytically inactive RBL10S240A (RBL10/RBL10S240A was used as a prey, Fig. S1b) suggesting that proteolytic activity is not required for the observed interactions.

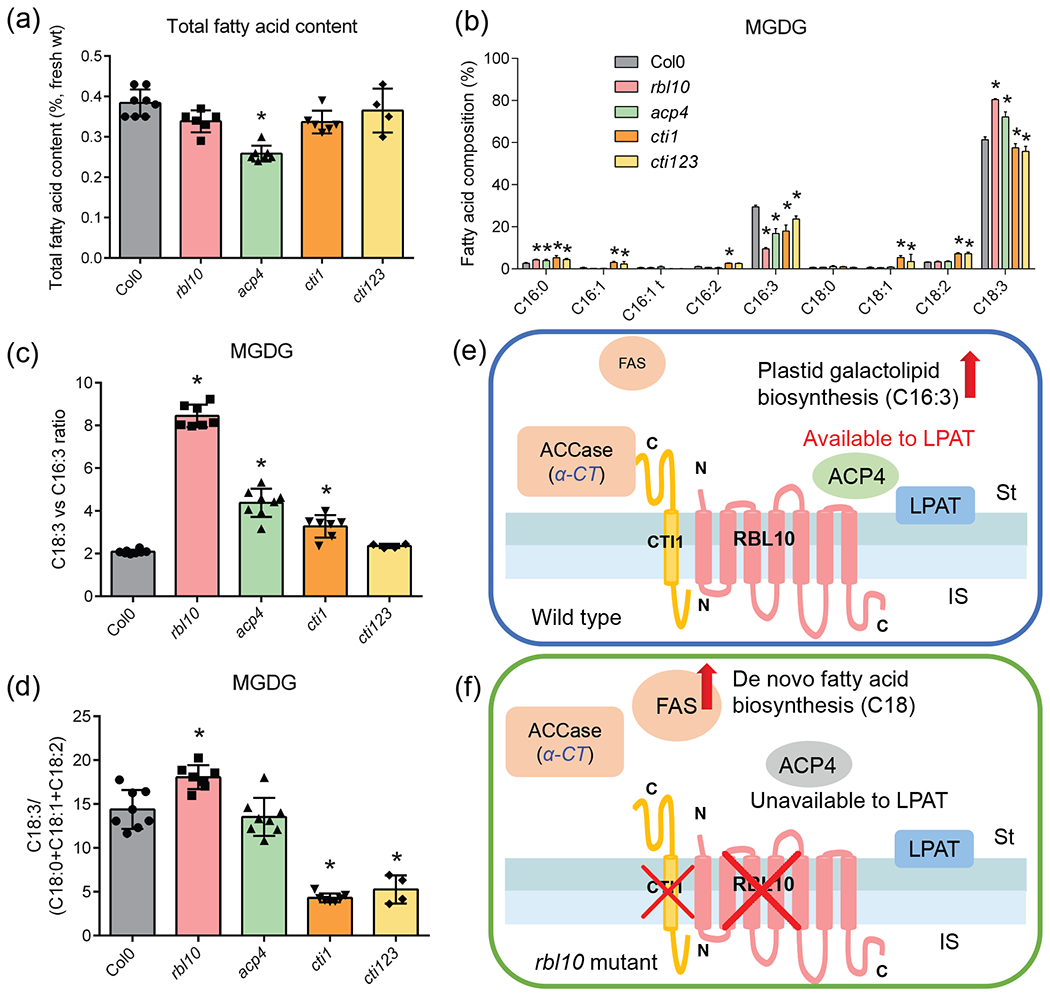

The acp4 Mutant Partially Replicates the rbl10 Lipid Phenotype

Among the presumed RBL10 interactors, ACP4 and CTI1 have previously been shown to be involved in lipid biosynthesis (Branen et al. 2003, Ye, et al. 2020) (Fig. 3). To explore whether their inability to interact with RBL10 might be related to the observed lipid phenotype of the rbl10 mutant, we obtained T-DNA insertion mutants for ACP4 and CTI1 and a cti123 triple mutant (CRISPR mediated knockout for all three CTI genes in Arabidopsis; (Ye, et al. 2020) to see if they replicate lipid aspects of the rbl10 phenotype (Fig. 4). The rbl10, cti1 and cti123 mutant lines looked normal and had no significant change in total leaf lipid content relative to wild type, while the acp4 mutant was pale and had a 33% decrease in lipid content (Fig. 4a). Acyl composition analysis of individual lipid classes showed that similar to, but less pronounced than rbl10, acp4 had reduced levels of C16:3 and increased levels of C18:3 in monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) (Fig. 4b). The cti mutants, on the other hand, showed slight decreases in C16:3 and C18:3 and concomitant increases in C16:0, C16:1, C16:2, C18:1 and C18:2 (Fig. 4b). The ratio of C18:3 over C16:3 acyl chains in rbl10 and acp4 was markedly increased whereas cti1 and cti123 showed only a slight or no increase in the acyl ratio, respectively (Fig. 4c), suggesting the availability of plastid lipid precursors for MGDG biosynthesis might be affected in the rbl10 and acp4 mutants. Consistent with a previous report (Ye, et al. 2020), the desaturation of C18 fatty acids was reduced in cti1 and cti123 with a substantial decrease in the ratio of C18:3 over the sum of C18:0, C18:1 and C18:2 (Fig. 4d), which is likely caused by the enhanced de novo fatty acid biosynthesis rate in these mutants (Ye, et al. 2020). On the contrary, rbl10 appears to have a slightly higher C18:3 desaturation ratio whereas no change in acp4 was noted (Fig. 4d). Taken together, the lipid characterization results confirmed that ACP4 and CTI1 might be important for plastid galactolipid (C16:3) biosynthesis and de novo fatty acid biosynthetic flux, respectively, with the acp4 mutant partially replicating some of the rbl10 lipid phenotypes.

Figure 4. Lipid characterization of leaves from the acp4, cti1, cti123 and rbl10 mutant plants.

(a) Total fatty acid content per fresh weight. (b) Fatty acid composition of MGDG. (c) Ratio of C18:3 to C16:3 fatty acids in MGDG. (d) Ratio of C18:3 to the sum of C18:0, C18:1 and C18:2 fatty acids in MGDG. (e) and (f) Proposed interaction of RBL10 with ACP4 and CTI1 in chloroplast lipid assembly. Data represent the mean ± S.D., n=4-8 of independent lines. Fatty acid composition is presented as a mole percentage of total fatty methyl esters. Asterisks indicate significant differences in the lipid content of mutant lines and control lines (t-test, P < 0.05).

Catalytic Mutant Constructs of RBL10 Cannot be Stably Introduced into rbl10-1

The causal relationship between the observed lipid phenotype in the rbl10 mutants and the RBL10 gene was previously shown by rescuing the mutant line with a wild-type copy of RBL10 (Lavell, et al. 2019). This provided a possible opportunity to test whether the proteolytic function of RBL10 is important to its role in lipid homeostasis. Towards this end, predicted active site residue point mutants, RBL10S240A and RBL10S240A;H293A were generated using PCR mutagenesis and the respective coding fragments were inserted into the same pEARLEYGATE101 plant expression vector that was used for the wild-type sequence, which contained a BASTA herbicide marker for screening transformants (Lavell, et al. 2019). Contrary to the wild-type construct, the floral dipping transformation protocol for the point mutant constructs of RBL10 using Agrobacterium tumefaciens did not yield any transformants in the rbl10-1 mutant background in two independently conducted experiments and after thousands of seeds screened with BASTA selection. A similar result was observed when the mutant constructs were introduced into the wild-type background. This suggested that the introduction of presumably inactive RBL10 protein causes embryo lethality in the rbl10-1 and wild-type backgrounds, with the mutant construct behaving like a dominant negative mutation as the loss-of-function rbl10-1 mutant is viable. Using isolated pea chloroplasts, the presumed catalytic mutant proteins were imported just as the wild-type protein (Fig. 5) likely ruling out mislocalization of the active site mutant proteins as cause for the observed embryo-lethality. These results precluded one possible avenue to verify the predicted in vivo protease activity of RBL10.

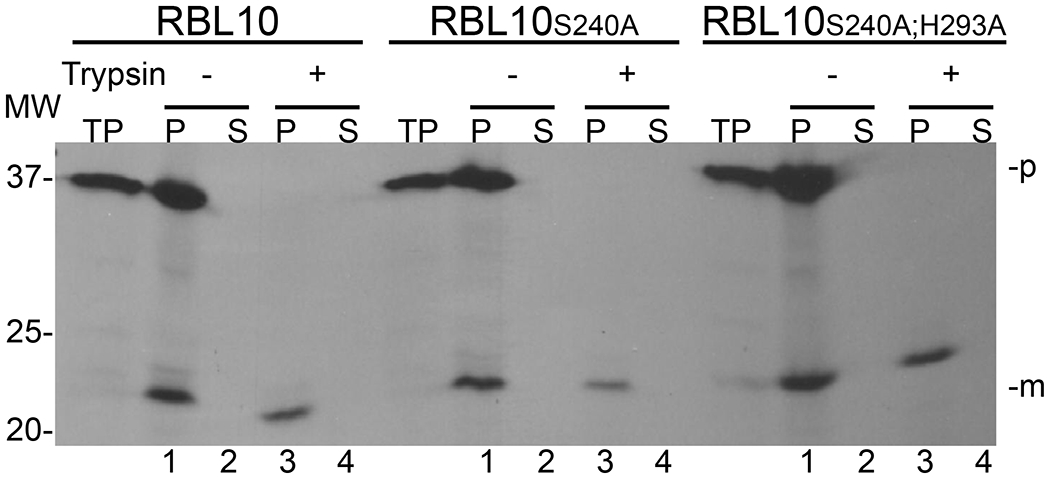

Figure 5. Import of RBL10 and its catalytic mutants into pea chloroplasts.

To observe import, 3H-radiolabeled RBL10, RBL10S240A, or RBL10S240A;H293A were incubated with isolated pea chloroplasts, at room temperature, in the presence of ATP and light. After incubation, each import was treated with (+) or without (−) Trypsin. After quenching of protease, the intact chloroplasts were recovered by centrifugation through a Percoll cushion, lysed, and fractionated into total membrane (P) and soluble (S) fractions. All fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and signals visualized by fluorography using X-Ray film. Successfully imported and processed RBL10 proteins can be seen as the lower band in the membrane fractions shown in Lanes 1 across the panel. Lanes 3 show that the imported RBL10 proteins are protected from trypsin digestion and are retained in the membrane pellet. TP- translation product used in import assay; p - precursor form of protein; m - mature form of protein after transit peptide has been processed upon import.

RBL10 Likely Has a Seventh Transmembrane Segment Creating an “In-Out” Topology Across the Inner Envelope Membrane

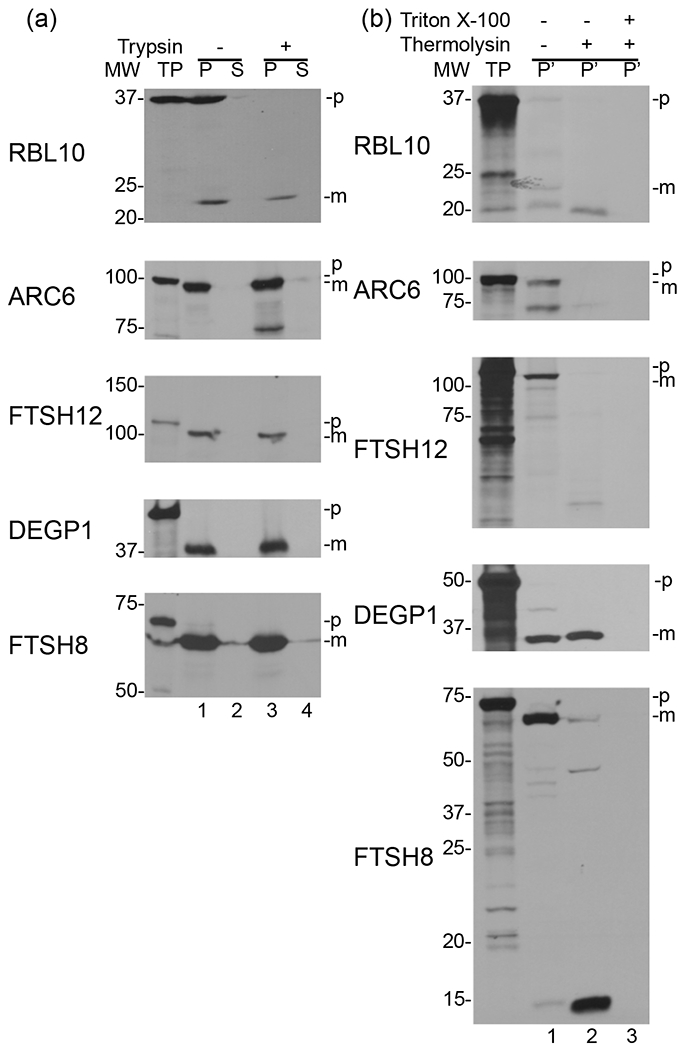

Rhomboid family members can be subcategorized based on their catalytic site, number of transmembrane helices, and subcellular organization, with RBL10 labeled as a six transmembrane Secretase-B type (Lemberg and Freeman 2007). However, it seems that not all members fall perfectly into each category leaving room for divergent members in each subtype. Initial studies investigating RBL10 assumed a six TM topology with both the amino- and carboxy-terminus facing the chloroplast stroma and those six helices homologous to the E. coli GlpG TMs (Lavell, et al. 2019). These six TMs only represent about half of the amino acids in the RBL10 sequence (Fig. S2). Due to lack of structural information on rhomboids outside of homologous sequences covered by GlpG, little is known about the soluble regions of RBL10. To investigate this aspect, we used the open source algorithms of PredictProtein (https://www.predictprotein.org) (Yachdav et al. 2014) to predict secondary structures or other notable features of these soluble regions. The results showed that RBL10 could contain a number of protein interaction sites as well as an intrinsically disordered region at the NTD (Fig. S3). To our surprise, in addition to a number of interesting features of the soluble regions, a seventh transmembrane domain was predicted at the CTD of RBL10 (Fig. S3) (Altschul et al. 1997). We then further investigated the in vivo topology importing H3-labeled RBL10 into isolated pea chloroplasts, followed by generating inside-out envelope membranes (Fig. 6). Upon initial import and treatment with trypsin, we observe a band about 24 kDa in size representative of the mature and protected RBL10 after processing, suggesting that the transit peptide of 13kDa is much larger than was predicted by sequence alone (Fig. 6a). When the inside-out envelope membranes were further treated with thermolysin there was a size shift of about 4 kDa suggesting that an additional section of RBL10 was processed (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6. Determining the topology of RBL10 within the inner envelope membrane using a dual protease strategy.

(a) In vitro translated 3H-labeled RBL10, ARC6, FTSH12, DEGP1, and FTSH8 were imported into isolated pea chloroplasts, then treated with (+) or without (−) Trypsin and separated by fractionation into membrane (P) and soluble (S) fractions. (b) A portion of the membrane fraction (P) from lane 3 in (a) of each protein import was further treated with (+) or without (−) Thermolysin in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Triton X-100. Inside out envelope membranes (P’) were recovered with right-side out thylakoids by centrifugation or, in samples containing TritonX-100, by acetone precipitation. All membrane fractions (P’) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and fluorography onto X-Ray film. TP - translation product added to import assay; p - precursor protein; m - mature protein. Lane 1 of the top panel shows a band for the mature RBL10 protein while lane 2 of the top panel shows a band indicating the fragment of RBL10 protected from Thermolysin digestion after inversion of the envelope membranes. In the third panel down the protected 37 kDa fragment of FTSH12 in lane 2 serves as a control. All protected protein fragments are accessible to Thermolysin in lane 3 due to the presence of TritonX-100.

Discussion

The RBL10 containing complex appears to represent another example of a protein complex involved in lipid metabolism in the inner chloroplast envelope membrane of Arabidopsis. Furthermore, it may be an example that rhomboids exist in larger complexes, perhaps higher order oligomers. Currently, knowledge about the oligomeric states of lipid biosynthetic enzymes and rhomboids, or multiprotein complexes in which they play a possible role, is generally lacking. One complex involved in PA binding and lipid transport from the ER to the chloroplast is an ABC transporter consisting of TRIGALACTOSYLDIACYLGLYCEROL 1, 2, and 3 (Awai et al. 2006, Lu and Benning 2009, Lu et al. 2007, Roston et al. 2012, Xu et al. 2005, Yang et al. 2017), which likely interacts with two additional proteins, TGD4 and 5 (Fan et al. 2015, Wang et al. 2012, Xu et al. 2008). Though the TGD complex is also of a large molecular weight, the RBL10 complex is different from the TGD complex using different sizing approaches. One might surmise that the RBL10 complex contains the substrate of this presumed intramembrane protease. Rhomboids are generally slow at catalysis and potentially probe non-substrate peptides, with secretase type rhomboids ultimately ejecting one or both substrate fragments from the membrane (Lemberg and Freeman 2007). Due to this fact, true rhomboid/substrate interactions may not be easily captured though some possible candidates emerged in this work.

From the coimmunoprecipitated proteins that were independently shown to interact with RBL10, the predicted envelope protein STR10 has a probable single-pass transmembrane (TM) segment. STR10 is encoded by At3g08920 and has a rhodanese-like domain. Rhodanese domains typically confer the activity of sulfurtransferases with a cysteine persulfide site, and 19 such proteins are predicted in Arabidopsis with functions varying from involvement in arsenate tolerance, cysteine metabolism, to the biosynthesis of hydrogen sulfide, a signaling molecule (Moseler et al. 2020, Selles et al. 2019). Though interaction was observed between STR10 and RBL10, this could be due to the nature of a rhomboid “scanning” through the membrane for its substrate (Kreutzberger, et al. 2019). Further analysis of the function of this protein will be necessary to determine whether the observed interaction has biological significance or whether it is a substrate of RBL10.

Another rhomboid interactor, ZKT has been previously linked to the formation of Photosystem II (PSII) super complexes under fluctuating light conditions, suggesting a role in light stress repair of PSII (Bhuiyan, et al. 2015). Likewise involved in light stress response and photosystem repair is FTSH1, a metalloprotease (At1g50250) included in the list of proteins which interact with RBL10. Known for its role in specifically degrading the D1 component during PSII repair, FTSH1 itself assembles into a hexameric heterocomplex and the oligomerization or the stability of this complex is partially modulated by the phosphorylation status of FTSH (Kato and Sakamoto 2019, Zhang et al. 2010). Although both FTSH1 and ZKT are known to be associated with the thylakoids facing the stroma (Lindahl et al. 1996) and RBL10 is in the inner envelope membrane, their interaction implies an ability to come into proximity with one another at some point during their lifetime. Contact sites between the envelopes and thylakoids or vesicle transport are possible mechanisms for transport of lipids or membrane-bound proteins from the envelopes to the thylakoids (Hertle et al. 2020, Lindquist and Aronsson 2018). Their interaction could be transient during import into the plastid, or possibly mediated through membrane proximity later on.

One of the more surprising interactors of RBL10 was PGK1, an enzyme of the Calvin-Benson cycle. PGKs in the plastid seem to be required for the maintenance of the photosynthetic membranes as the pgk1pgk2 double loss-of function mutant can survive only when grown on medium supplemented with sucrose and other Calvin-Benson intermediates, but remains a stunted albino plant with altered thylakoid ultrastructure (Li et al. 2019). The albino phenotype of pgk1 pgk2 was further attributed to a disruption of the plastid pathway of galactolipid biosynthesis as lipidomic analysis of the mutant plants detail a reduction in MGDG and DGDG with acyl groups indicative of plastid lipid assembly (Li, et al. 2019). A second Calvin-Benson cycle enzyme determined to interact with RBL10, SBPase, seems to affect vegetative growth and photosynthetic efficiency where sbp mutants plants are pale and severely stunted in growth (Liu et al. 2012). However, the over-production of SBPase leads to an increase in leaf area and biomass (Simkin et al. 2017). While we expect substrates of RBL10 to be membrane-bound proteins, association with soluble interactors to mediate their rhomboid function has been observed with the yeast Rbd2 recruiting a AAA-ATP-ase Cdc48 to a soluble CTD of Rbd2 (Hwang et al. 2016). The significance of RBL10 interacting with proteins involved in thylakoid repair or carbohydrate metabolism is not yet clear, however, it potentially points to a role in other major processes than lipid metabolism.

Of particular interest in view of the lipid phenotype of the rbl10 mutant are two proteins involved in chloroplast lipid biosynthesis, ACP4 and CTI1, which showed interaction with RBL10 in our two assays. We asked the question whether the lipid phenotype of the individual acp4 and cti1 loss-of-function mutants could be informative with regard to the observed lipid phenotype of the rbl10 mutant. Indeed, loss of ACP4 causes a reduction of C16:3 containing MGDG species repeating one aspect of the lipid phenotype of rbl10, although not to the same extent (Fig. 4). Changes in fatty acid composition or lipid content of the cti1 and cti123 mutants were subtle in our hands (Fig. 4). However, it was recently shown that CTI1 is a direct interactor of ACCase and that its removal leads to enhanced de novo fatty acid biosynthesis (Ye, et al. 2020). It seems reasonable to hypothesize that when RBL10 is present, the interaction of RBL10 with ACP4 and CTI1 locates ACP4 and ACCase at the stroma face of the inner envelope membrane, which promotes substrate channeling (Fig. 4e, f). The formation of C16-ACP4 and the subsequent channeling of C16-ACP4 substrate to lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (LPAT) may thus facilitate plastid galactolipid biosynthesis. Without its interaction of RBL10, ACP4 might not be able to associate with the membrane and thus C16-ACP4 might be less available to LPAT. Our previous analysis of rbl10 showed that PA biosynthesis in isolated rbl10 plastids and its conversion to diacylglycerol is functional, while MDGD biosynthesis from plastid-derived PA is not, implying that the transfer of PA through the inner envelope membrane is disrupted in the rbl10 mutant (Lavell, et al. 2019). Therefore, it seems possible that LPAT might be able to use other acyl-ACPs in the absence of RBL10, but that the resulting PA molecular species are a less preferred substrate for transfer through the membrane. When RBL10 is absent, the CTI1 level is reduced in the envelope membrane as shown in a previous proteomics study (Knopf, et al. 2012), and de novo fatty acid biosynthetic flux should therefore be enhanced (Ye, et al. 2020) and could contribute to the accumulation of PA as previously observed in isolated rbl10 chloroplasts (Lavell, et al. 2019). Admittedly, without knowing the mechanistic nature of movement of PA through the inner envelope membrane, the role of ACP4 or CTI1 in this process remains speculative and further analysis beyond the scope of this work here will be required to test this interesting hypothesis.

We observed differences in apparent RBL10 complex sizes by BN-PAGE (Fig. 1) and size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2). This may be due to the fact that the RBL10 complexes are vulnerable to dissociation and that during the harsher BN-PAGE procedure the lower strength-interactors dissociate leaving a core complex of approximately 250 kDa behind. Indeed, the RBL10 complexes might even be dynamic, considering the unusually rapid nature of rhomboid diffusion through the membrane (Kreutzberger, et al. 2019). The RBL10 protein complexes were observed using the RBL10-YFP-HA fusion protein (Figs. 1 and 2, Table 1). Although our previous work has confirmed that RBL10-YFP-HA is able to complement the lipid phenotype of the rbl10 mutant (Lavell, et al. 2019) and a YFP tag has been included in the Co-IP coupled to MS analysis in many other studies (Daras et al. 2019), we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the identified proteins that co-immunoprecipitated with RBL10 might be due to their interactions with the YFP tag. Therefore, we independently validated the interaction of RBL10 with individual proteins from the Co-IP list (Table 1) using a split ubiquitin assay. Under the chosen experimental setup, RBL10 cannot interact with itself but was able to directly interact with nine proteins from the list (Fig. 3). Although these independently verified direct interactors have a total MW of about 299 kDa, not too different from the complex size observed by BN-PAGE, we have no further information how they relate to the composition of the large RBL10 complexes observed by size exclusion chromatography (with a MW of about >660 kDa; Fig. 1). With less than half of the candidates from the immunoprecipitation shown to interact with RBL10 in the split ubiquitin assay, although some could not be tested in both assays due to their resistance to cloning, the prospect of the candidates interacting with one another rather than directly with RBL10, remains a possibility. For example, despite being found in each of the 3 replicates of the Co-IP, RPS1 did not interact directly with RBL10 in the split-ubiquitin assays. With a large molecular weight complex as observed for RBL10 by BN-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography, it is likely that only a few components interact directly with RBL10. Seeing a few potential interactors containing single transmembrane spanning domains present in only a single replicate of the Co-IP might suggest transient interactions or a protease/substrate relationship, and there may be additional transient interactions not captured by this approach. To fully address the question of the composition of the observed RBL10 complexes in the future, it will be necessary to develop additional tools such as specific antibodies against the postulated components followed by immunodetection of these components in the complex observed by BN-PAGE (Fig 1) or in fractions obtained by size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2). In addition, immunodetection might aid in the purification of the native complex by conventional methods and mass spectrometry analysis of the purified complex should provide further information of its composition.

Thus far, RBL10 has been considered a 6 transmembrane domain rhomboid. However, upon analysis with PredictProtein, a seventh transmembrane domain can be hypothesized making RBL10 a 6+1 secretase type. This additional pass through the membrane at the CTD would create an NTD-in CTD-out topology for RBL10 (Fig. 3b). If stromal residents interact with the soluble NTD region of RBL10, a ubiquitin fragment on the other side of the yeast membrane would not be able to come into proximity with its partner fragment, providing an explanation why RBL10 interactors can only be seen when RBL10 is tagged on the NTD. Since the topology of RBL10 has been proposed to have the NTD facing the stroma, this spatial arrangement suggests that the CTD points into the intermembrane space. This would be consistent with evidence of RBL10 interactions with stroma residents with its soluble NTD. We were able to see additional processing of RBL10 when pea chloroplast membranes were inverted and treated with thermolysin, but at this time it is difficult to interpret if this is solely due to processing of the NTD or if for example the CTD or a loop between TM6 and TM7 is accessible to the protease (Fig. S4).

Our inability to recover any rbl10-1 mutants in multiple independent experiments when we tried to introduce presumably inactive catalytic-site mutants of RBL10, suggests that these catalytic site mutants are toxic in the developing embryo, while loss-of-function mutants are viable. Knowing that RBL10 occurs in a complex, this dominant-negative phenotype suggests that an inactive and toxic complex is formed which does not seem to be the case when RBL10 is completely absent. The significance of this finding is not fully clear, but it could suggest that RBL10’s proteolytic activity is important in proper complex assembly or turnover and that the catalytic mutants disrupt this process during development. Testing the proteolytic activity of RBL10 has remained challenging but understanding its protein interactions with other chloroplast proteins may help understand the native conditions under which it may be proteolytically active. The human rhomboid PARL participates in regulating mitochondria turnover and its proteolytic activity is modulated by phosphorylation of the NTD (Shi and McQuibban 2017). Outside the native context of the mitochondrion where PARL is phosphorylated, any investigations of the proteolytic activity of PARL in vitro have yielded little information. In analogy, it seems possible that RBL10 possesses functional requirements for proteolytic activity in vivo we have yet to replicate in vitro.

Overall, the RBL10 protein interactome described, especially its direct interactions with the two lipid players ACP4 and CTI1, raises new questions how RBL10 affects chloroplast lipid biosynthesis and leads to new hypotheses. Exploring the mechanisms by which RBL10 affects the transfer of PA through the envelope membrane, and how ACP4 and possibly CTI1 might contribute to this process will allow us to gain deeper insights into the chloroplast lipid assembly.

Materials and Methods

T-DNA lines, Plant Growing Conditions and Chloroplast Isolation

Seeds for T-DNA lines disrupting RBL10, ACP4 and CTI1 were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) with the accession numbers of SALK_036100, SALK_099519C, and SALK_099125C, respectively. All lines were genotyped for homozygosity. The cti123 triple mutant was kindly provided by Dr. Jay J. Thelen (University of Missouri-Columbia). Plant lines were used as noted in each experiment including Col-0 (wild type), rbl10-1, the rbl10-1 complemented line expressing RBL10-YFP-HA under the 35S Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) promoter using the pEARLEYGATE101 vector, acp4, cti1 and cti123. The predicted active site residue point mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Heckman and Pease 2007). The sequences were inserted into the pEARLEYGATE101 vector to generate the rbl10-1 lines expressing the RBL10-YPF-HA mutant versions as described previously (Lavell, et al. 2019). Plant growth conditions, isolation of chloroplasts, and import assays, were performed as previously described (Lavell, et al. 2019).

Determining Topology Using Isolated Chloroplasts and Import Assays

Membranes from chloroplasts containing imported RBL10 were recovered as described in Li et al., (Li et al. 2017). Briefly, after import of RBL10, intact chloroplasts were recovered by centrifugation through a 40% Percoll cushion and then hypotonically lysed resulting in the generation of a mixture of inside-out inner envelope membrane vesicles and right-side out thylakoids vesicles which were subsequently treated with (+) or without (−) Thermolysin. Protease reactions were terminated with EDTA and treated membranes were recovered by centrifugation and further analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The control proteins ARC6 and FTSH12, both inner envelope membrane proteins and FTSH8, a thylakoid membrane protein were used to confirm the integrity of inside-out inner envelope membrane vesicles and right-side out thylakoid vesicles, respectively.

All precursor proteins used in import assays were radiolabeled using [3H]-Leucine (approximately 0.05mCi/50ul) and translated using Promega’s TNT® Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After translation, all 3H-labeled precursors were diluted with an equal volume of ‘cold’ 50mM L-Leucine in 2X Import Buffer (IB) prior to their addition to import assays. Import and protease protection assays were performed as previously described (Lavell, et al. 2019).

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblot Analysis

SDS-PAGE was carried out using Bio-Rad precast 10-12% acrylamide gels (https://www.bio-rad.com), or hand-cast 10-12% acrylamide gels. Samples were boiled in Laemmli buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL pH6.8, 2% SDS, 0.1% Bromophenolblue, 10% glycerol at 1x) at 95°C for 10 mins, centrifuged for 3 minutes at 13,000 rpm, loaded onto gels and separated using 150V at RT. Resulting gels were either stained (1.25 g Coomassie brilliant blue, 400 mL methanol, 100 mL glacial acetic acid, 500 mL dH2O) or were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using the wet transfer method with a Tris-Glycine buffer (25 mM Tris, 192mM Glycine, 20% methanol). Protein transfer was achieved with 100 V over 1.5 h chilled on ice with stirring. A 5% milk solution in TBS-T (100 mM Tris, 155 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) was used to block non-specific binding to the membrane, which was then incubated with the antibody specified in a 5% milk-TBS-T solution for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Washes between primary and secondary antibodies and before detection were performed with TBS-T buffer, washing the blot three times for 5-15 mins each time. Chemiluminescence was used to detect presence of protein of interest.

Blue Native PAGE

Chloroplasts isolated from Arabidopsis seedlings were freshly prepared on the day of use and were pelleted at 700 x g; then proteins were solubilized in the BN-PAGE protein solubilization buffer consisting of 333 μL of 3x Gel Buffer (150 mM Bis-tris/HCL, 1.5 M 6-aminocapronic acid, pH 7.0), 125 μL of 80% glycerol, 100 μL of 10% n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM), 10 μL of 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and water to a final volume of 1 mL. The final concentration of DDM was 1% and the final chlorophyll concentration was 1 mg/mL chlorophyll equivalents. The solution was incubated on ice for 10 mins with occasional tapping to mix. The solubilized chloroplast lysate was clarified with a 20 min centrifugation at 18,000 x g at 4°C. The clarified supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and 1/10 volume of a BN-PAGE sample buffer [5% (w/v) SERVA Blue G (SERVA No. 35050)] was added to each supernatant. An unstained native gel marker was used for size reference (NativeMark; www.ThermoFisher.com). Chloroplast protein complexes were separated on a 4-13% BN-PAGE gel according to (Jarvi et al. 2011). BN-PAGE electrophoresis was performed at 0°C with a gradual increase in the voltage as follows: 75 V for 30 min, 150 V for 30 min, followed by 200 V until the sample reached the end of the gel (total running time was approximately 2 h) (Jarvi, et al. 2011). The resulting gel was either stained using Coomassie Brilliant Blue or transferred to a PVDF membrane for Immunoblot analysis. To transfer the proteins to PVDF, the BN-PAGE gel was incubated in a solution containing 0.1% w/v SDS, 1% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 50 mM Tris buffer, pH9.0 for 30 min at room temperature with gentle mixing. The gel was then briefly washed three times with distilled water and then incubated in transfer buffer to remove excess SDS and reducing agent for 15 min at room temperature. Proteins were then transferred to PVDF as described above. Finally, the resulting PVDF membrane was fixed in 8% acetic acid. Any transferred dye was removed with methanol, followed by washing with water. Immunoblot analysis proceeded as follows: RBL10-YFP-HA was detected using an anti-HA antibody from mouse at 1:1000 dilution (HA-Tag-6E2, Mouse mAh #2367; CellSignal.com) and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS-T, the membrane was further incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (G21040; www.ThermoFisher.com) at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was washed with TBS-T, and protein signals were detected using Pierce™ enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) western blot detection reagents (32109; www.ThermoFisher.com). Blots were then exposed to X-ray film (#248300; rpicorp.com) for various times and subsequently developed.

Size Exclusion Chromatography

A standard protein mixture was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Catalog# 69385), including thyroglobulin (670k Da), bovine γ-globulins (150 kDa), chicken egg albumin (44.3 kDa), bovine ribonuclease A type I-A (13.7 kDa), and p-aminobenzoic acid (137 Da). The standard protein mixture was supplied as a lyophilized powder corresponding to 30 mg of protein. The powder was resuspended with 1 mL of deionized water and any undissolved solids were removed with centrifugation. A GE Superdex 200 (www.gelifesciences.com) column was equilibrated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 with 0.01% DDM at 4°C. A 100 μL injection loop was used to load 100 μL of the standard mixture onto the equilibrated column. Proteins were separated by size exclusion chromatography using a GE AKTA purifier system (www.gelifesciences.com) at 0.05 mL/min. Fractions of 0.5 mL were collected from the time of injection. A total of 72 fractions were collected, equal to 1.5 times column volume. Protein elution was monitored by absorbance at 280 nm, signals corresponding to individual proteins in the standard mixture were observed for reference. Chloroplasts isolated from Arabidopsis seedlings were freshly prepared, using the rbl10-1 complemented line expressing RBL10-YFP-HA. Chloroplasts were pelleted at 700 x g; then proteins were solubilized in the BN-PAGE protein solubilization buffer as described above to a concentration of 1 mg/mL chlorophyll equivalent, allowing the solution to incubate on ice for 30 mins with occasional tapping to mix. The resulting chloroplast lysate was clarified with a 10 min centrifugation at 100,000 x g. The supernatant was removed and 100 μL, equal to 100 μg chlorophyll equivalents, were loaded onto a Superdex 200 SEC column equilibrated with PBS pH 7.4 with 0.01% β-dodecyl-n-maltoside (DDM). The chloroplast lysate was separated at 0.05 mL/min flow rate using the same method as the standard mixture. Again, A280 was used to monitor protein elution off the column. Standard proteins were confirmed with SDS-PAGE of the fractions corresponding to the A280 signals. Elution of RBL10-YFP-HA was observed by immunoblot analysis of the resulting fractions in the same range as the A280 signals for the standards, using an anti-HA antibody from rat directly conjugated to HRP at a 1:1000 dilution (3F10, Roche/Sigma Aldrich, www.sigmaaldrich.com).

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Magnetic Dynabeads with Protein G were prepared prior to the experiment. Mouse IgG specific for hemagglutinin (HA) (Biolegend 16b32) and a mouse K-isotype control IgG were coupled to the Protein G Dynabeads, using 7.5 μg per 50 μL of beads. Chloroplast protein lysate was prepared as described above for BN-PAGE without the addition of SERVA Blue G dye. Each set of IgG coupled Dynabeads was incubated with the chloroplast protein lysate at room temperature with end over end mixing for 1 h. Beads were collected with a magnet, supernatant removed, and the beads were washed three times with 1x PBS pH 7.4, DDM 0.02%. The resulting beads were submitted for mass spectrometry identification of peptides present.

Samples were washed with ice-cold 50mM ammonium bicarbonate, 3x and finally resuspended in 10 μL of 5 ng/μL trypsin in the same buffer. Beads were incubated at 37°C for 5 h to digest proteins. Supernatant was removed following centrifugation, placed into a new tube and the peptide solution acidified by adding trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to 3%. Samples were then purified using C18 stage-tips (Shevchenko et al. 1996) and dried by vacuum centrifugation. Peptides were re-suspended in 2% acetonitrile/0.1%TFA to 20 μL. From this, 10μL were automatically injected by EASYnLC 1200 (www.thermo.com) onto a Thermo Acclaim PepMap RSLC 0.1 mm x 20 mm C18 trapping column and washed with Buffer A for ~5min. Bound peptides were eluted onto a Thermo Acclaim PepMap RSLC 0.075 mm x 500 mm C18 analytical column over 35 min with a gradient of 8%B to 40%B in 24 min, ramping to 90%B at 25 min and held at 90%B for the duration of the run (Buffer A = 99.9% Water/0.1% Formic Acid, Buffer B = 80% Acetonitrile/0.1% Formic Acid/19.9% Water). Column temperature was maintained at 50°C using an integrated column heater (PRSO-V2, www.sonation.com).

Eluted peptides were introduced into a ThermoFisher Q-Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (www.thermo.com) using a FlexSpray spray ion source. Survey scans were taken in the Orbi trap (60000 resolution, determined at m/z 200) and the top 10 ions in each survey scan were then subjected to automatic higher energy collision induced dissociation (HCD) with fragment spectra acquired at 15,000 resolution. The resulting MS/MS spectra were converted to peak lists using Mascot Distiller, v2.6.1 (www.matrixscience.com) and searched against all entries in the TAIR, v10, protein sequence database (downloaded from The Arabidopsis Information Network, www.arabidopsis.org), appended with common laboratory contaminants (downloaded from www.thegpm.org, cRAP project), using the Mascot searching algorithm, v 2.6. The Mascot output was then analyzed using Scaffold Q+S, v4.9.0 (www.proteomesoftware.com) to probabilistically validate protein identifications. Assignments validated using the Scaffold 1%FDR confidence filter were considered true.

Proteins unique to the RBL10-YFP-HA sample or twice as abundant compared to the control samples in at least 2 of the 3 experimental replicates were considered putative protein interactors. The protein names, gene IDs, molecular weight, net enrichment as well as the occurrence throughout experimental replicates is shown in Table 1.

Split Ubiquitin Interaction Assays

Co-immunoprecipitation, as described above, identified potential interactors of RBL10. Arabidopsis ORFs were amplified from wild type cDNA using gene-specific primers with B1 and B2 linkers as follows: forward primers (ACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTATG-X-5’ ORF) and reverse primers (ACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTA-X-3’ ORF). Primers were designed to omit the predicted transit peptide sequence of the candidate (Table S1). Amplified cDNAs were cloned using the pGEM-Teasy vector and successful transformants were confirmed by sequencing. The PCR was repeated with the gene specific B1 and B2 linker primers for in vivo cloning in yeast. NubG fusions were cloned in vivo with the pNXgate33-3HA and THY.AP5 competent cells using the “LiAc transformation of yeast” protocol as described in (Obrdlik, et al. 2004). THY.AP5 transformed cells were plated on synthetic complete (SC) medium lacking tryptophan (W), uracil (U), and methionine (M) (SC/+AHL). CubPLV fusions were cloned in vivo with the pMetYCgate and THY.AP4 competent cells using the same protocol as used for the NubG fusions. THY.AP4 transformed cells were plated on synthetic complete (SC) medium lacking leucine (L) and methionine (M) (SC/+AHTU). Recipes for media are summarized in Table S2. Single colonies of both NubG and CubPLV fusions were cultured at 28°C in the appropriate SC medium. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) medium at a 5x concentration (i.e., 1 mL of culture in the appropriate SC medium can be resuspended in 200 mL of YPD medium). 250 μL of resuspended culture was sufficient for 10 mating combinations. For a single mating, 25 μL of each mating type were combined in a sterile 96-well plate well. Once all combinations were plated, the plate was sealed with a lid and taped with micropore tape. The cells were mated for 6-8 hours at 28°C with shaking. A multichannel pipettor was used to spot mated cells onto plates for consistency across interaction assays. 6-10 μL of each crossing was pipetted onto synthetic minimal medium with 0 and 150 μM methionine, denoted SD/+ 0 μM Met and SD/+ 150 μM Met respectively. Crossings were also plated onto two SC/+AH and one YPD plate. Plates were incubated at 28°C for 3-4 days. Growth on SD/+ 0 μM Met and SD/+ 150 μM Met media indicated a successful reconstitution of N-Ubiquitin and C-Ubiquitin fragments due to protein-protein interaction. The addition of 150 μM Met is not required; however, it offered a more selective growth test that indicates stronger interactions. Growth on YPD medium indicated that cell reduced viability was not the reason for lack of growth on SD/+ 0 μM Met and SD/+ 150 μM Met plates. Colonies on SC/+ AH medium grew white if there was protein-protein interaction, while red colonies indicated a lack thereof. Colonies on SC/+ AH medium were used to test for interactions based on β-gal activity. This was completed with the “X-Gal Overlay Assay” protocol from (Obrdlik, et al. 2004). Interactions were confirmed with colonies producing blue pigment. KAT1(At5g46240) + pNXgate33-3HA bearing cells were mated with cells transformed with pMetYCgate (EV) and pNXgate33-3HA (EV) with pMetYCgate (EV) providing negative controls for interaction assays. KAT1 in both the pNXgate33-3HA and pXNgate33-3HA along with KAT1 in pMetYCgate provided positive control combinations for the interaction assays. KAT1 is an Arabidopsis K+ channel known to dimerize and the KAT1 vectors were purchased along with the other empty vectors used in the mbSUS kit (Obrdlik, et al. 2004).

Leaf Lipid Analysis

Lipids were extracted from 5-6-week old Arabidopsis rosette leaves, and were separated on a silica TLC plate treated with (NH4)2SO4 using acetone:toluene:water (91:30:7 v/v) as previously described (Lavell, et al. 2019). Lipid bands were visualized with brief iodine vapor staining, scraped and trans-methylated for GC analysis. Fatty acid composition is presented as a mole percentage of total fatty methyl esters.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Little is known about the function of plant rhomboid proteases such as RBL10, which is a chloroplast located rhomboid protease previously shown to affect the lipid composition of photosynthetic membranes. Here we provide evidence for an RBL10 containing complex in the chloroplast and identify several protein interactors including ACP4 and CTI1 which have roles in lipid metabolism.

Acknowledgement

This work was possible due to the help and generosity of many individuals. For performing the size exclusion chromatography, Dr. Curtis Wilkerson graciously allowed the use of his Akta instrument and columns as well as provided valuable insight. Dr. Mingzhu Fan provided training critical to carrying out the chromatography experiments. For valuable discussions on co-immunoprecipitation experiments and BN-PAGE, we are grateful to Dr. Tomomi Takeuchi. For providing support and guidance on identifying co-immunoprecipitated proteins we thank Doug Whitten at the MSU Proteomics Core. We also thank Dr. Jay J. Thelen from the University of Missouri-Columbia for providing the cti123 triple mutant. Financial support for this work was primarily from the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy (Grant DE-FG02-91ER20021). In addition, Anastasiya Lavell was partially supported by a fellowship from Michigan State University under the Training Program in Plant Biotechnology for Health and Sustainability (T32-GM110523).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relating to this manuscript.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W and Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res, 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awai K, Xu CC, Tamot B and Benning C (2006) A phosphatidic acid-binding protein of the chloroplast inner envelope membrane involved in lipid trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103, 10817–10822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battey JF and Ohlrogge JB (1990) Evolutionary and tissue-specific control of expression of multiple acyl-carrier protein isoforms in plants and bacteria. Planta, 180, 352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergbold N and Lemberg MK (2013) Emerging role of rhomboid family proteins in mammalian biology and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1828, 2840–2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan NH, Friso G, Poliakov A, Ponnala L and van Wijk KJ (2015) MET1 is a thylakoid-associated TPR protein involved in photosystem II supercomplex formation and repair in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 27, 262–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventure G and Ohlrogge JB (2002) Differential regulation of mRNA levels of acyl carrier protein isoforms in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol, 128, 223–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branen JK, Shintani DK and Engeseth NJ (2003) Expression of antisense acyl carrier protein-4 reduces lipid content in Arabidopsis leaf tissue. Plant Physiol, 132, 748–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Baker RP, Ji M and Urban S (2019) Ten catalytic snapshots of rhomboid intramembrane proteolysis from gate opening to peptide release. Nat Struct Mol Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daras G, Rigas S, Alatzas A, Samiotaki M, Chatzopoulos D, Tsitsekian D, Papadaki V, Templalexis D, Banilas G and Athanasiadou A-M (2019) LEFKOTHEA regulates nuclear and chloroplast mRNA splicing in plants. Developmental cell, 50, 767–779. e767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan JL, Zhai ZY, Yan CS and Xu CC (2015) Arabidopsis TRIGALACTOSYLDIACYLGLYCEROL5 interacts with TGD1, TGD2, and TGD4 to facilitate lipid transfer from the endoplasmic reticulum to plastids. Plant Cell, 27, 2941–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M (2016) Rhomboids, signalling and cell biology. Biochem Soc Trans, 44, 945–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Lorenzo M, Sjodin A, Jansson S and Funk C (2006) Protease gene families in Populus and Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol, 6, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman KL and Pease LR (2007) Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc, 2, 924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertle AP, Garcia-Cerdan JG, Armbruster U, Shih R, Lee JJ, Wong W and Niyogi KK (2020) A Sec14 domain protein is required for photoautotrophic growth and chloroplast vesicle formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 117, 9101–9111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Ribbens D, Raychaudhuri S, Cairns L, Gu H, Frost A, Urban S and Espenshade PJ (2016) A Golgi rhomboid protease Rbd2 recruits Cdc48 to cleave yeast SREBP. Embo Journal, 35, 2332–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa A, Tanaka H, Kato C, Iwasaki Y and Asahi T (2005) Molecular characterization of the ZKT gene encoding a protein with PDZ, K-Box, and TPR motifs in Arabidopsis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 69, 972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvi S, Suorsa M, Paakkarinen V and Aro EM (2011) Optimized native gel systems for separation of thylakoid protein complexes: novel super- and mega-complexes. Biochem J, 439, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelen F, Oleksy A, Smietana K and Otlewski J (2003) PDZ domains - common players in the cell signaling. Acta Biochim Pol, 50, 985–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaraju DV, Xu L, Letellier MC, Bandaru S, Zunino R, Berg EA, McBride HM and Pellegrini L (2006) Phosphorylation and cleavage of presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein (PARL) promotes changes in mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103, 18562–18567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaoka MM, Urban S, Freeman M and Okada K (2005) An Arabidopsis Rhomboid homolog is an intramembrane protease in plants. FEBS Lett, 579, 5723–5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y and Sakamoto W (2019) Phosphorylation of the chloroplastic metalloprotease FtsH in Arabidopsis characterized by Phos-Tag SDS-PAGE. Front Plant Sci, 10, 1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopf RR, Feder A, Mayer K, Lin A, Rozenberg M, Schaller A and Adam Z (2012) Rhomboid proteins in the chloroplast envelope affect the level of allene oxide synthase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J, 72, 559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberger AJB, Ji M, Aaron J, Mihaljevic L and Urban S (2019) Rhomboid distorts lipids to break the viscosity-imposed speed limit of membrane diffusion. Science, 363, 10.1126/science.aao0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavell A, Froehlich JE, Baylis O, Rotondo AD and Benning C (2019) A predicted plastid rhomboid protease affects phosphatidic acid metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J, 99, 978–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JR, Urban S, Garvey CF and Freeman M (2001) Regulated intracellular ligand transport and proteolysis control EGF signal activation in Drosophila. Cell, 107, 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberg MK and Freeman M (2007) Functional and evolutionary implications of enhanced genomic analysis of rhomboid intramembrane proteases. Genome Res, 17, 1634–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Qiu Z, Wang X, Gong P, Xu Q, Yu QB and Guan Y (2019) Pooled CRISPR/Cas9 reveals redundant roles of plastidial phosphoglycerate kinases in carbon fixation and metabolism. Plant J, 98, 1078–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Martin JR, Aldama GA, Fernandez DE and Cline K (2017) Identification of putative substrates of SEC2, a chloroplast inner envelope translocase. Plant Physiol, 173, 2121–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl M, Tabak S, Cseke L, Pichersky E, Andersson B and Adam Z (1996) Identification, characterization, and molecular cloning of a homologue of the bacterial FtsH protease in chloroplasts of higher plants. J Biol Chem, 271, 29329–29334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist E and Aronsson H (2018) Chloroplast vesicle transport. Photosynth Res, 138, 361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XL, Yu HD, Guan Y, Li JK and Guo FQ (2012) Carbonylation and loss-of-function analyses of SBPase reveal its metabolic interface role in oxidative stress, carbon assimilation, and multiple aspects of growth and development in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant, 5, 1082–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B and Benning C (2009) A 25-amino acid sequence of the Arabidopsis TGD2 protein is sufficient for specific binding of phosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem, 284, 17420–17427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Xu C, Awai K, Jones AD and Benning C (2007) A small ATPase protein of Arabidopsis, TGD3, involved in chloroplast lipid import. J Biol Chem, 282, 35945–35953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner C, Lorenz H, Weihofen A, Selkoe DJ and Lemberg MK (2011) The mitochondrial intramembrane protease PARL cleaves human Pink1 to regulate Pink1 trafficking. J Neurochem, 117, 856–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moin SM and Urban S (2012) Membrane immersion allows rhomboid proteases to achieve specificity by reading transmembrane segment dynamics. Elife, 1, e00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseler A, Selles B, Rouhier N and Couturier J (2020) Novel insights into the diversity of the sulfurtransferase family in photosynthetic organisms with emphasis on oak. New Phytol, 226, 967–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrdlik P, El-Bakkoury M, Hamacher T, Cappellaro C, Vilarino C, Fleischer C, Ellerbrok H, Kamuzinzi R, Ledent V, Blaudez D, Sanders D, Revuelta JL, Boles E, Andre B and Frommer WB (2004) K+ channel interactions detected by a genetic system optimized for systematic studies of membrane protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 101, 12242–12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa-Tellez S, Anoman AD, Alcantara-Enguidanos A, Garza-Aguirre RA, Alseekh S and Ros R (2020) PGDH family genes differentially affect Arabidopsis tolerance to salt stress. Plant Sci, 290, 110284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa-Tellez S, Anoman AD, Flores-Tornero M, Toujani W, Alseek S, Fernie AR, Nebauer SG, Munoz-Bertomeu J, Segura J and Ros R (2018) Phosphoglycerate kinases are co-regulated to adjust metabolism and to optimize growth. Plant Physiol, 176, 1182–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roston RL, Gao J, Murcha MW, Whelan J and Benning C (2012) TGD1, -2, and -3 proteins involved in lipid trafficking form ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter with multiple substrate-binding proteins. J Biol Chem, 287, 21406–21415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selles B, Moseler A, Rouhier N and Couturier J (2019) Rhodanese domain-containing sulfurtransferases: multifaceted proteins involved in sulfur trafficking in plants. J Exp Bot, 70, 4139–4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O and Mann M (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem, 68, 850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G and McQuibban GA (2017) The Mitochondrial Rhomboid Protease PARL Is Regulated by PDK2 to Integrate Mitochondrial Quality Control and Metabolism. Cell Rep, 18, 1458–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin AJ, Lopez-Calcagno PE, Davey PA, Headland LR, Lawson T, Timm S, Bauwe H and Raines CA (2017) Simultaneous stimulation of sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphosphatase, fructose 1,6-bisphophate aldolase and the photorespiratory glycine decarboxylase-H protein increases CO2 assimilation, vegetative biomass and seed yield in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol J, 15, 805–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson LG, Strisovsky K, Clemmer KM, Bhatt S, Freeman M and Rather PN (2007) Rhomboid protease AarA mediates quorum-sensing in Providencia stuartii by activating TatA of the twin-arginine translocase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104, 1003–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EP, Smith SG and Glover BJ (2012) An Arabidopsis rhomboid protease has roles in the chloroplast and in flower development. J Exp Bot, 63, 3559–3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toujani W, Munoz-Bertomeu J, Flores-Tornero M, Rosa-Tellez S, Anoman A and Ros R (2013) Identification of the phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase isoform EDA9 as the essential gene for embryo and male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav, 8, e27207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi LP and Sowdhamini R (2006) Cross genome comparisons of serine proteases in Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Genomics, 7, 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S, Lee JR and Freeman M (2002) A family of Rhomboid intramembrane proteases activates all Drosophila membrane-tethered EGF ligands. Embo J, 21, 4277–4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Xu C and Benning C (2012) TGD4 involved in endoplasmic reticulum-to-chloroplast lipid trafficking is a phosphatidic acid binding protein. Plant J, 70, 614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Fan J, Froehlich JE, Awai K and Benning C (2005) Mutation of the TGD1 chloroplast envelope protein affects phosphatidate metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 17, 3094–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CC, Fan JL, Cornish AJ and Benning C (2008) Lipid trafficking between the endoplasmic reticulum and the plastid in Arabidopsis requires the extraplastidic TGD4 protein. Plant Cell, 20, 2190–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachdav G, Kloppmann E, Kajan L, Hecht M, Goldberg T, Hamp T, Honigschmid P, Schafferhans A, Roos M, Bernhofer M, Richter L, Ashkenazy H, Punta M, Schlessinger A, Bromberg Y, Schneider R, Vriend G, Sander C, Ben-Tal N and Rost B (2014) PredictProtein--an open resource for online prediction of protein structural and functional features. Nucleic Acids Res, 42, W337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zienkiewicz A, Lavell A and Benning C (2017) Coevolution of domain interactions in the chloroplast TGD1, 2, 3 lipid transfer complex specific to brassicaceae and poaceae plants. Plant Cell, 29, 1500–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye YJ, Nikovics K, To A, Lepiniec L, Fedosejevs ET, Van Doren SR, Baud S and Thelen JJ (2020) Docking of acetyl-CoA carboxylase to the plastid envelope membrane attenuates fatty acid production in plants. Nat Commun, 11, 6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Kato Y, Zhang L, Fujimoto M, Tsutsumi N, Sodmergen W (2010) The FtsH protease heterocomplex in Arabidopsis: dispensability of type-B protease activity for proper chloroplast development. Plant Cell, 22, 3710–3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.