Abstract

Simple Summary

The insect order Dermaptera is commonly known as earwigs. The earwigs have many interesting biological characteristics, such as epizoic on other small animals, viviparous, and maternal care on their eggs and young nymphs. The external morphology of earwigs has been studied in detail, but their genetic characteristics remain unclear. The phylogenetic position of Dermaptera among all insect orders and the inner relationship of Dermaptera are largely unsolved. To better understand the molecular characters of earwigs, we sequenced and analyzed two mitogenomes of an earwig species from the family Haplodiplatyidae. The results revealed the existence of intraspecific variation and extensive gene rearrangement events in the mitogenomes of earwigs. The phylogenetic results are partially similar to previous studies. The discoveries in this study could provide new information for the molecular diversity and mitogenomic evolution of earwigs.

Abstract

Haplodiplatyidae is a recently established earwig family with over 40 species representing a single genus, Haplodiplatys Hincks, 1955. The morphology of Haplodiplatyidae has been studied in detail, but its molecular characters remain unclear. In this study, two mitogenomes of Haplodiplatys aotouensis Ma & Chen, 1991, were sequenced based on two samples from Fujian and Jiangxi provinces, respectively. These represent the first mitogenomes for the family Haplodiplatyidae. The next-generation sequencing method and subsequent automatic assembly obtained two mitogenomes. The two mitogenomes of H. aotouensis were generally identical but still exhibit a few sequence differences involving protein-coding genes (PCGs), ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, control regions, and intergenic spacers. The typical set of 37 mitochondrial genes was annotated, while many transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were rearranged from their ancestral locations. The calculation of nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates in PCGs indicated the fastest evolving nd4l gene in H. aotouensis. The phylogenetic analyses supported the basal position of Apachyidae but also recovered several controversial clades.

Keywords: earwigs, Haplodiplatyidae, mitogenomes, gene rearrangement, phylogeny

1. Introduction

The hemimetabolous insect order Dermaptera, commonly known as earwigs, is a relatively small and primitive group of terrestrial insects comprising over 1900 extant species worldwide [1,2]. The earwigs can be easily distinguished from other insects in the adult stage by the pincer-like, unsegmented cerci, which have various functions in defense, prey capture, wing folding, and mating [3,4]. Most earwigs are free-living and oviparous, while a few species are epizoic on vertebrate hosts and viviparous [5]. The earwigs mainly feed on plant material, whereas some groups are predators or scavengers. The females of earwigs will protect their eggs from the attack of predators and clean the eggs with their mouthparts; they also feed the first-instar nymphs [6,7].

The monogeneric family Haplodiplatyidae was established based on the genus Haplodiplatys Hincks, 1955, which was originally included in another family, Diplatyidae [8,9]. The paraphyly of Diplatyidae sensu lato (including current Diplatyidae and Haplodiplatyidae) has already been proposed by earlier morphological studies [4,10,11,12]. The genus Haplodiplatys comprises over 40 species, one of which was described from Miocene Mexican amber [2,13,14]. The species Haplodiplatys aotouensis Ma & Chen, 1991, was originally described from Fujian Province of southeast China [15] and was later included in the monograph of Chen & Ma (2004) [16]. No related studies were conducted for H. aotouensis since then, however, its occurrence in neighboring provinces is continuously witnessed by insect collectors.

Despite the efforts using either morphological or molecular data, the phylogenetic position of Dermaptera and the inner relationships between dermapteran taxa remain largely unsolved [17,18,19,20]. Research on the genetic characters of earwigs is relatively weaker than traditional morphological studies. Research of the widely used genetic marker, mitochondrial genome (mitogenome), is rather little in Dermaptera when compared with other insects [21]. To date, the complete or nearly complete mitogenomes of only six species have been sequenced and analyzed (Table 1) [17,20]. Some common mitogenomic characteristics of earwigs and the preliminary phylogenetic results are summarized in Chen (2022) [20] but require further confirmation with more mitogenomic data. In this study, we sequenced and analyzed the mitogenomes of H. aotouensis based on samples collected from two different geographic locations. The study aims to investigate the intraspecific mitogenomic variation, the common mitogenomic structural characters, and the phylogenetic relationships of earwigs.

Table 1.

List of species used in this study.

| Family | Species | Length (bp) | A + T% | Accession Number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplodiplatyidae | Haplodiplatys aotouensis Ma & Chen, 1991 (Fujian) | 16,134 | 71.7 | ON186792 | this study |

| Haplodiplatys aotouensis Ma & Chen, 1991 (Jiangxi) | 16,222 | 71.9 | ON186793 | this study | |

| Apachyidae | Apachyus feae de Bormans, 1894 | 19,029 | 61.2 | MW291948 | [20] |

| Diplatyidae | Diplatys flavicollis Shiraki, 1907 | 12,950 | 73.5 | MW291949 | [20] |

| Pygidicranidae | Challia fletcheri Burr, 1904 | 20,456 | 72.6 | NC_018538 | [17] |

| Anisolabididae | Euborellia arcanum Matzke & Kočárek, 2015 | 16,087 | 68.3 | KX673196 | [22] |

| Forficulidae | Eudohrnia metallica (Dohrn, 1865) | 16,324 | 58.7 | KX091853 | GenBank |

| Paratimomenus flavocapitatus Shiraki,1906 | 15,677 | 67.4 | KX091861 | GenBank | |

| Perlidae (Plecoptera) | Kamimuria chungnanshana Wu, 1938 | - | - | NC_028076 | [23] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Collection and DNA Extraction

Two samples of H. aotouensis were respectively collected from Wuyishan Natural Reserve (27.7464° N, 117.6838° E), Fujian Province, in March of 2022, and Wuyi Mountain (27.9803° N, 117.78071894° E), Jiangxi Province, in May of 2021. The specimens were identified as H. aotouensis by the author. The collected specimens were preserved in 100% ethanol until used for the total genomic DNA extraction by E.Z.N.A. Tissue DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA).

2.2. Mitogenome Sequencing and Assembly

The TruSeq DNA Library (insert size = 400 bp) was constructed using at least 1 μg of DNA according to standard protocols. The library was sequenced by Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform (Nanjing Personal Gene Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) with paired-end reads of 2 × 150 bases. Clean reads were obtained by removing unpaired, short, and low-quality raw reads. The high-quality reads were assembled by the GetOrganelle pipeline v 1.7.4 [24]. The two mitogenomes were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers ON186792 and ON186793.

2.3. Mitogenome Annotation and Analysis

The MITOS online server was used to annotate the assembled mitogenomes and predict the secondary structure of the tRNA genes [25]. The annotation results were validated and corrected by homology alignments with other earwigs and the NCBI’s ORF Finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/, accessed on 1 May 2022). The mitogenome structure and GC skews were visualized by the CGView Server (http://stothard.afns.ualberta.ca/cgview_server/, accessed on 1 May 2022) [26]. MEGA-X was used to calculate nucleotide composition, codon usage, and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) [27]. The composition skew values in the mitogenome were calculated using the following formulas [28]: AT-skew = (A − T)/(A + T) and GC-skew = (G − C)/(G + C). The probable mitochondrial rearrangement scenarios during the evolution of H. aotouensis and other earwigs were predicted by CREx (Common Interval Rearrangement Explorer) online server [29] using Drosophila yakuba Burla, 1954 as a reference [30,31]. The synonymous substitution rate (Ks) and nonsynonymous substitution rate (Ka) were calculated using KaKs_Calculator v 2.0 [32]. Tandem repeats in the mitogenome were identified using the online tool Tandem Repeats Finder (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.advanced.submit.html, accessed on 1 May 2022) [33].

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

The mitogenome sequences of the other six species of Dermaptera and an outgroup from Plecoptera were downloaded from GenBank and used in the phylogenetic analysis (Table 1). The nucleotide sequences of PCGs were aligned by MUSCLE in MEGA X with default settings of codon mode [34,35] and manually trimmed for length consistency. DAMBE 6.4.42 [36] was used to calculate the substitution saturation of the two rRNA genes and each codon position of the PCGs under the GTR model or F84 model when an error occurs. Due to the lack of several PCGs in Diplatys flavicollis Shiraki, 1907 (Diplatyidae), and the results of substitution saturation plots, atp8, cox1, cox2, nad2, nad4l, and nad6, the third codon positions of the other seven PCGs, and the two rRNA genes were excluded from the nucleotide dataset. The first two codon positions of the remaining seven PCGs were concatenated into a combined nucleotide dataset using SequenceMatrix v 1.7.8 [37]. Another amino acid dataset was established by translation of the concatenated nucleotide sequence of the seven PCGs, including all codon positions. PartitionFinder v 2.1.1 was used to evaluate the best substitution models and partitioning schemes for the nucleotide dataset with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and a greedy search algorithm [38]. Each dataset was used to conduct three phylogenetic inferences, including Phylo–Bayesian (PB) inference, Bayesian inference (BI), and maximum likelihood (ML) analysis. PB inferences for both datasets were performed with the site-heterogeneous model CAT + GTR (two independent chains, constant sites removed, gamma-distributed rates with four categories) implemented in Phylobayes v 3.3 [39]. MrBayes v 3.2.7 was employed to construct the BI trees for both datasets, running four independent Markov chains for 20 million generations and sampled every 1000 generations [40]. A burn-in of 25% was used to generate the consensus tree. RAxML v 8.2.12 was used to construct the ML trees for both datasets, with 1000 bootstrap replicates [41]. FigTree v 1.4.2 was employed to edit and visualize the phylogenetic trees.

3. Results

3.1. Mitogenome Structure and Nucleotide Composition

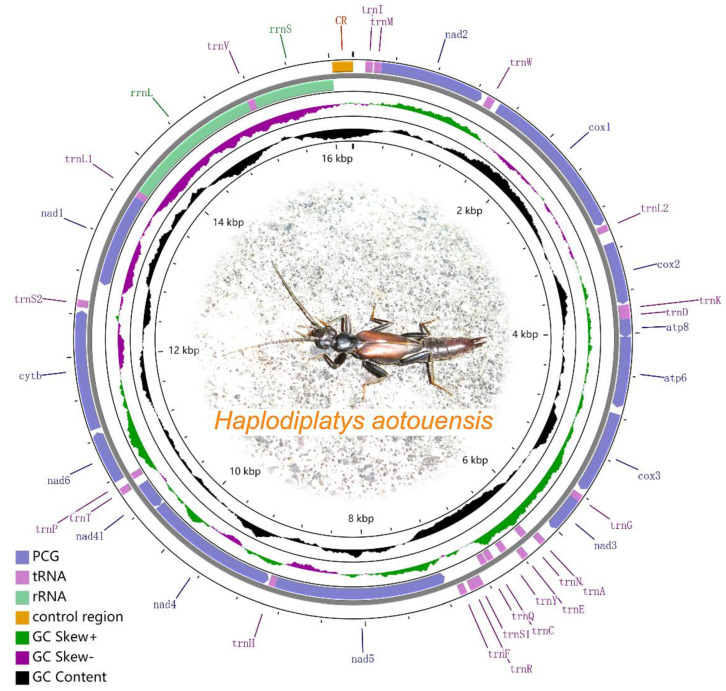

The two mitogenomes obtained from two geographic areas are highly identical (99.4%), which confirms both to be the same species (Figure 1). The H. aotouensis mitogenome from Fujian Province is 16,134 bp long whereas the mitogenome from Jiangxi Province is 16,222 bp in length (Table 2). Both mitogenomes consist of the standard set of 37 genes (13 PCGs, 22 tRNA genes, and two rRNA genes), however, differ in the following aspects: cox1, cox2, and nad6 genes each have one different base on position 951, 300, and 384, respectively; rrnS gene of Jiangxi’s sample has one additional base in the middle section than Fujian’s sample; length difference of four intergenic regions; length difference of the control regions (Table 2). The majority J-strand had 24 genes and the minority N-strand has the remaining 14 genes. In the mitogenomes of H. aotouensis, a total of four overlapping regions were found, ranging in size from 1 to 7 bp. The longest overlapping region was found between atp8 and atp6 (Table 2). There are also 23 intergenic spacers ranging in size from 2 to 178 bp and the longest gene spacer was located between trnS2 and nad1 (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Consensus mitogenome structure of Haplodiplatys aotouensis. The map is generated based on Fujian’s sample. Genes outside the map are transcribed clockwise, while those inside the map are transcribed counterclockwise. Names and other details of the genes are listed in Table 2. The inside circles show the GC content and the GC skew. GC content and GC skew are plotted as the deviation from the average value of the entire sequence.

Table 2.

Mitochondrial genome structure of Haplodiplatys aotouensis. Values of Fujian’s (left) and Jiangxi’s (right) samples are separated by semicolons.

| Gene | Position (bp) | Size (bp) | Strand | Intergenic Nucleotides | Anticodon | Start/Stop Codons | A + T% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trnI | 119−188; 119−188 | 70; 70 | J | 0; 0 | GAT; GAT | 72.9; 72.9 | |

| trnM | 200−271; 200−271 | 72; 72 | J | 11; 11 | CAT; CAT | 75.0; 75.0 | |

| nad2 | 272−1270; 272−1270 | 999; 999 | J | 0; 0 | ATT/TAA; ATT/TAA | 70.4; 70.4 | |

| trnW | 1310−1388; 1310−1388 | 79; 79 | J | 39; 39 | TCA; TCA | 73.4; 73.4 | |

| cox1 | 1446−2945; 1446−2945 | 1500; 1500 | J | 57; 57 | ATT/TAA; ATT/TAA | 65.9; 65.9 | |

| trnL2 | 2957−3023; 2957−3023 | 67; 67 | J | 11; 11 | TAA; TAA | 68.7; 68.7 | |

| cox2 | 3134−3724; 3134−3724 | 591; 591 | J | 110; 110 | ATT/TAG; ATT/TAG | 67.2; 67.3 | |

| trnK | 3732−3797; 3732−3797 | 66; 66 | J | 7; 7 | CTT; CTT | 63.6; 63.6 | |

| trnD | 3797−3865; 3797−3865 | 69; 69 | J | −1; −1 | GTC; GTC | 76.8; 76.8 | |

| atp8 | 3866−4039; 3866−4039 | 174; 174 | J | 0; 0 | ATT/TAA; ATT/TAA | 72.4; 72.4 | |

| atp6 | 4033−4710; 4033−4710 | 678; 678 | J | −7; −7 | ATG/TAA; ATG/TAA | 70.5; 70.5 | |

| cox3 | 4769−5557; 4770−5558 | 789; 789 | J | 58; 58 | ATG/TAA; ATG/TAA | 65.4; 65.4 | |

| trnG | 5598−5665; 5599−5669 | 68; 68 | J | 40; 40 | TCC; TCC | 79.4; 79.4 | |

| nad3 | 5666−6019; 5667−6020 | 354; 354 | J | 0; 0 | ATT/TAA; ATT/TAA | 69.8; 69.8 | |

| trnA | 6130−6196; 6139−6205 | 67; 67 | J | 110; 118 | TGC; TGC | 80.6; 80.6 | |

| trnN | 6216−6289; 6225−6298 | 74; 74 | N | 19; 19 | GTT; GTT | 78.4; 78.4 | |

| trnE | 6338−6406; 6349−6417 | 69; 69 | J | 48; 50 | TTC; TTC | 75.4; 75.4 | |

| trnY | 6467−6537; 6478−6548 | 71; 71 | N | 60; 60 | GTA; GTA | 83.1; 83.1 | |

| trnC | 6624−6690; 6635−6701 | 67; 67 | N | 86; 86 | GCA; GCA | 86.6; 86.6 | |

| trnQ | 6700−6768; 6711−6779 | 69; 69 | N | 9; 9 | TTG; TTG | 76.8; 76.8 | |

| trnS1 | 6816−6884; 6845−6913 | 69; 69 | J | 47; 65 | GCT; GCT | 72.5; 72.5 | |

| trnR | 6885−6950; 6914−6979 | 66; 66 | J | 0; 0 | TCG; TCG | 74.2; 74.2 | |

| trnF | 6987−7053; 7016−7082 | 67; 67 | J | 36; 36 | GAA; GAA | 83.6; 83.6 | |

| nad5 | 7130−8872; 7159−8901 | 1743; 1743 | N | 76; 76 | ATC/TAA; ATC/TAA | 71.1; 71.1 | |

| trnH | 8873−8941; 8902−8970 | 69; 69 | N | 0; −3 | GTG; GTG | 79.7; 79.7 | |

| nad4 | 8954−10303; 8983−10332 | 1350; 1350 | N | 12; 12 | ATG/TAA; ATG/TAA | 70.2; 70.2 | |

| nad4l | 10303−10590; 10332−10619 | 288; 288 | N | −1; −1 | ATG/TAA; ATG/TAA | 71.2; 71.2 | |

| trnT | 10599−10667; 10628−10696 | 69; 69 | J | 8; 8 | TGT; TGT | 76.8; 76.8 | |

| trnP | 10668−10734; 10697−10763 | 67; 67 | N | 0; 0 | TGG; TGG | 76.1; 76.1 | |

| nad6 | 10737−11237; 10766−11266 | 501; 501 | J | 2; 2 | ATT/TAG; ATT/TAG | 73.1; 73.3 | |

| c ytb | 11270−12409; 11299−12438 | 1140; 1140 | J | 32; 32 | ATG/TAA; ATG/TAA | 69.9; 69.9 | |

| trnS2 | 12438−12508; 12467−12537 | 71; 71 | J | 28; 28 | TGA; TGA | 84.5; 84.5 | |

| nad1 | 12687−13631; 12716−13660 | 945; 945 | N | 178; 178 | ATT/TAA; ATT/TAA | 66.2; 66.2 | |

| trnL1 | 13632−13700; 13661−13729 | 69; 69 | N | 0; 0 | TAG; TAG | 81.2; 81.2 | |

| rrnL | 13701−15108; 13730−15137 | 1408; 1408 | N | 0; 0 | − | 75.4; 75.4 | |

| trnV | 15109−15181; 15138−15210 | 73; 73 | N | 0; 0 | TAC; TAC | 72.6; 72.6 | |

| rrnS | 15182−15995; 15211−16025 | 814; 815 | N | 0; 0 | − | 75.4; 75.5 | |

| CR | 15996−16134; 16026−16222 | 139; 197 | J | 0; 0 | − | 77.0; 83.8 |

The two H. aotouensis mitogenomes are highly skewed towards A and T nucleotides, with an A + T content of 71.7% in Fujian’s sample and 71.9% in Jiangxi’s sample. Each of the 37 mitochondrial genes also has a rich A + T content ranging from 63.6% in trnK to 86.6% in trnC (Table 2). The AT skew is negative (−0.1), whereas the GC skew is positive (0.3) in both mitogenomes.

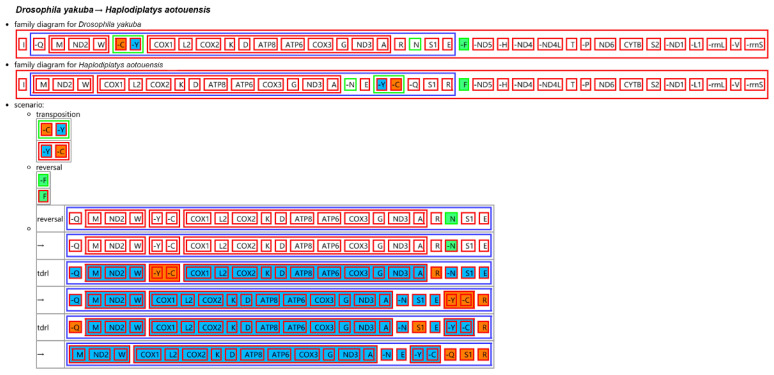

3.2. Gene Rearrangement

The gene order of the 13 PCGs of the two H. aotouensis mitogenomes is identical and conserved with all sequenced earwigs and the presumed ancestral arthropod mitochondrial gene arrangement of D. yakuba [20,31]. However, tRNA genes in the three gene clusters, trnI-Q-M, trnW-C-Y, and trnA-R-N-S1-E-F are rearranged, and such rearrangement pattern is not found in any sequenced earwigs [20]. The CREx analysis demonstrated that the gene order of the H. aotouensis mitogenomes is rearranged from the ancestral type of mitogenome of D. yakuba by the following steps (Figure 2): initial transposition of trnC and trnY; subsequent reversal of trnF and trnN; and two final tandem duplication and random loss (TDRL) events regarding trnY-trnC, trnR, trnQ, and trnS1.

Figure 2.

Reconstruction of mitochondrial gene rearrangement scenarios in the evolution of Haplodiplatys aotouensis. The ancestral mitochondrial gene arrangement of Drosophila yakuba is set as the reference. The tRNA genes are represented by the amino acid abbreviations. In each rearrangement event of the scenario, the upper box indicates the earlier arrangement of related genes, whereas the lower box indicates the rearranged gene order after the event.

3.3. PCGs

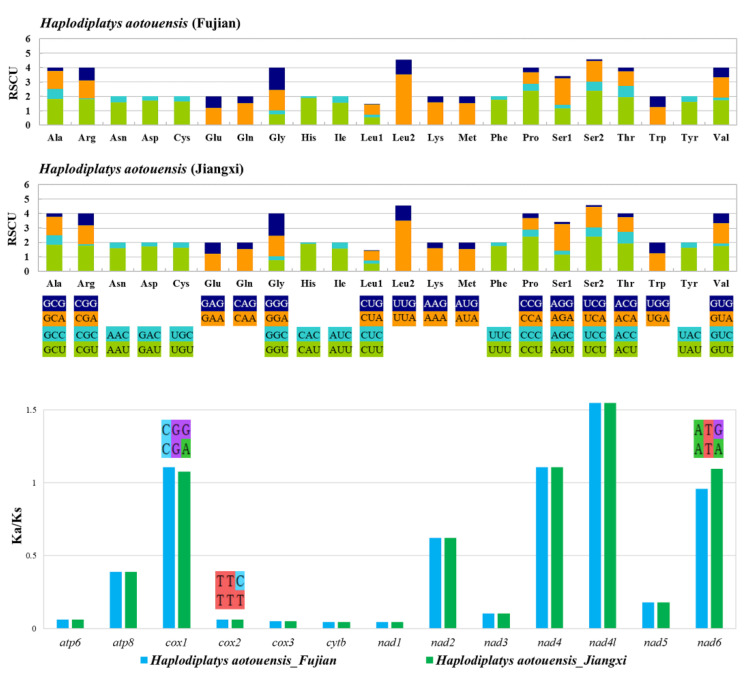

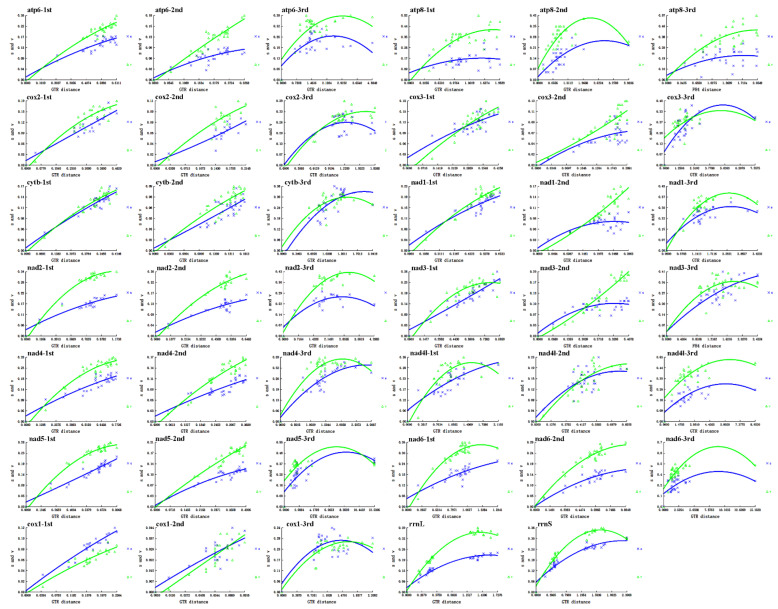

The 13 PCGs of H. aotouensis are similar in size to those of other sequenced earwigs [20]. All PCGs start with the standard ATN start codons (ATT, ATC, and ATG) and terminate with the complete stop codon TAN (TAA or TAG). The codon usage of PCGs was assessed by the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) value, which indicates the number of times a codon is repeated in relation to the uniform synonymous codon usage (Figure 3). Among the amino acid-encoding codons, TTA (Leu), TCT (Ser), and CCT (Pro) are the most frequently used. The ratio of Ka/Ks for each PCG was calculated to assess their evolutionary rates (Figure 3). The results indicate that nad4l has the highest evolutionary rate, followed by cox1, nad4, and nad6. The Ka/Ks ratios of cox1, cox2, and nad6 differ between the two geographical samples of H. aotouensis. The calculation also reveals a slightly higher evolution rate in cox1 and cox2 of Fujian’s sample and nad6 in Jiangxi’s sample. The ratios of four genes are above 1, indicating their evolution under positive selection. The remaining nine PCGs show much lower Ka/Ks ratios below 1, suggesting the existence of purifying selection in these PCGs.

Figure 3.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) and evolutionary rates of PCGs in Haplodiplatys aotouensis. In the Ka/Ks chart, t1he different codons between Fujian’s (upper) and Jiangxi’s (lower) samples are marked above the relevant PCGs.

3.4. tRNAs, rRNAs and the Control Region

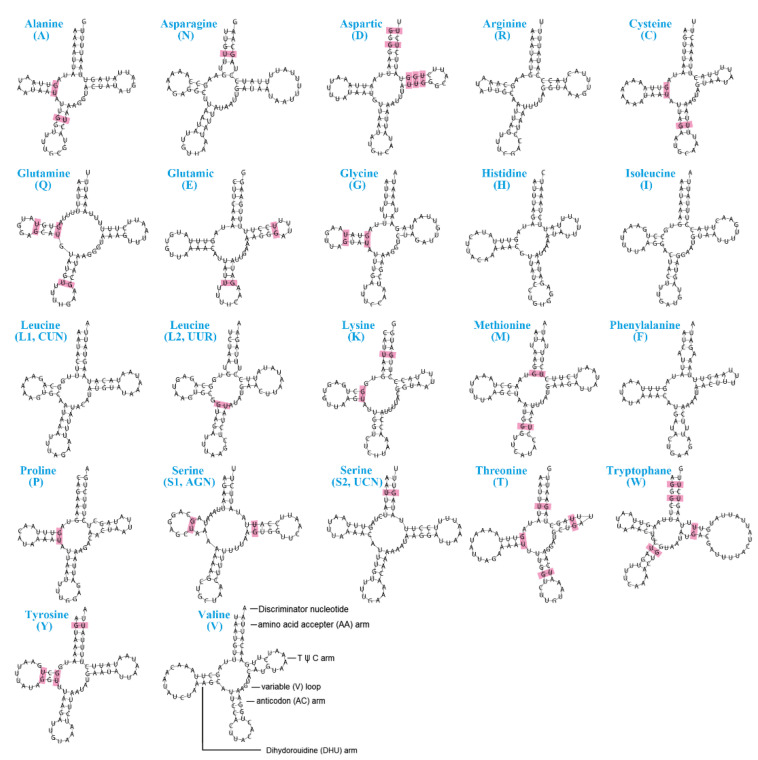

The two H. aotouensis mitogenomes both contain the canonical set of 22 tRNA genes and the nucleotide sequences of these genes are pairwise identical (Table 2). These tRNAs range in size from 66 to 79 bp, and the longest tRNA gene is trnW. Anticodons of the tRNA genes are identical to other sequenced earwigs. The predicted secondary structures for most of the tRNA genes are typical cloverleaf, whereas the dihydrouridine (DHU) arm of trnS1 is reduced into a small loop (Figure 4). A total of 37 mismatched base pairs are found in the secondary structure of 16 tRNA genes and all of them are mismatched G-U pairs.

Figure 4.

Secondary structures of tRNA genes in the mitogenome of Haplodiplatys aotouensis. Mismatched base pairs are indicated by red boxes.

The two rRNA genes, i.e., the large ribosomal RNA (rrnL) gene and small ribosomal RNA (rrnS) gene are found in the conserved location between trnL1 and the control region. The rrnL gene is 1408 bp in length with an A + T content of 75.4% in both mitogenomes of Fujian’s sample and Jiangxi’s sample. The rrnS gene exhibits a slight difference between the two mitogenomes, being 814 bp long in Fujian’s sample and 815 bp long in Jiangxi’s sample. The A + T content of rrnS gene is respectively 75.4% and 75.5% in Fujian’s and Jiangxi’s samples.

The two control regions are both shorter than 200 bp. The control region of Fujian’s sample is 139 bp long, with an A + T content of 77%; the control region of Jiangxi’s sample is 197 bp long, with a higher A + T content of 83.8%. Nucleotide sequences of the two control regions are identical on positions 1–93 and 94–139. Three copies of tandem repeats are detected near the 5′ end of both control regions and each copy of repeat comprises eight nucleotides, i.e., TACGCGTA. A subsequent poly-[TA]n stretch is also found near the 3′ end of both control regions but which is 8 bp long (4 TA units) in Fujian’s sample and 66 bp long (33 TA units) in Jiangxi’s sample. The length difference between the two control regions is caused by the different number of TA units.

3.5. Phylogenetic Analyses

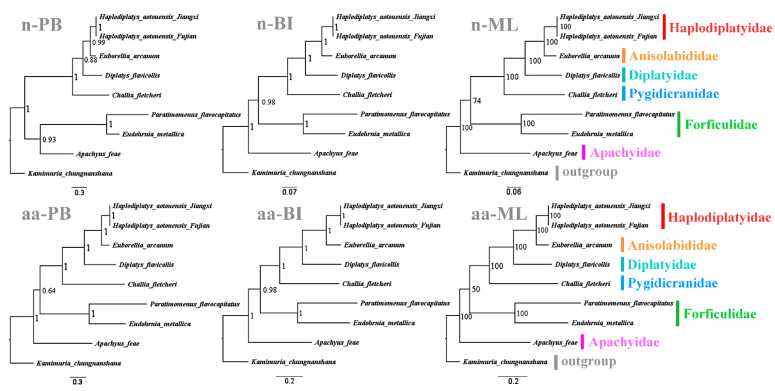

To obtain more reliable phylogenetic results, the analysis excluded cox1, cox2, and nad2 which are absent from D. flavicollis and the saturated genes. According to the saturation plots (Figure 5), atp8, nad4l, and nad6, the third codon positions of all PCGs, and the two rRNA genes are saturated and excluded from the nucleotide dataset. The final nucleotide dataset contains 4542 bases derived from seven PCGs. The amino acid dataset is composed of 2271 amino acids translated from the seven unsaturated PCGs including their third codon positions. Among the six phylogenetic trees (Figure 6), five have identical topological structures. In all trees, the two samples of H. aotouensis sequenced in this study are confidently clustered together; Haplodiplatyidae is supported as the sister group of Anisolabididae and their combined clade is grouped with Diplatyidae; Pygidicranidae is basal to the clade comprising Diplatyidae, Anisolabididae, and Haplodiplatyidae. In the PB tree using the nucleotide dataset, Apachyidae is recovered as the sister group of Forficulidae. In the other five trees, Apachyidae is supported as a single basal group of Dermaptera; Forficulidae is the sister group of the clade including Haplodiplatyidae, Anisolabididae, Diplatyidae, and Pygidicranidae.

Figure 5.

Substitution saturation plots per codon position for PCGs and per gene for rRNA. The plots of cox1 were calculated excluding the partial cox1 sequence of Diplatys flavicollis.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic relationships within Dermaptera inferred from mitogenomic data. Numbers at the nodes are posterior probabilities or bootstrap values. The family names are listed after the species. Abbreviations: n-PB, Phylo–Bayesian tree based on nucleotide dataset; n-BI, Bayesian tree based on nucleotide dataset; n-ML, maximum likelihood tree based on nucleotide dataset; aa-PB, Phylo–Bayesian tree based on amino acid dataset; aa-BI, Bayesian tree based on amino acid dataset; aa-ML, maximum likelihood tree based on amino acid dataset.

4. Discussion

The two mitogenomes of H. aotouensis samples in two geographic areas are almost identical regarding the mitogenome structure but exhibit variations in several PCGs, rrnS gene, and noncoding regions. Such intraspecific mitogenomic variation is reasonable for a widespread species but is seldomly studied in earwigs or other related insects. The single variable nucleotide in each of cox1, cox2, and nad6 is exclusively restricted to the third codon position and thus did not change the final protein product of these genes. The mutations on the third codon positions are considered neutral because they are usually synonymous with respect to the amino acids [42]. Such frequent mutations of the synonymously variable third codon positions have also been found in other insects [43]. The 1 bp difference in the middle section of the rrnS gene might be a random mutation driven by geographical isolation or simply a systematic mistake during the sequencing and assembling processes. The intraspecific difference in the non-coding regions could be attributed to their high rates of nucleotide substitution, insertions or deletions, and the presence of varying copy numbers of tandem repeats [44,45]. As a result, all intraspecific nucleotide differences of H. aotouensis did not shift the final protein products.

The mitogenomes of H. aotouensis are smaller in size than those of the completely sequenced Challia fletcheri Burr, 1904, and Apachyus feae de Bormans, 1894 [20,46,47], which is mainly due to the small control region. It is worth noting that control regions of several other earwig mitogenomes failed to be obtained by next-generation sequencing, which might be attributed to the high A and T content and the presence of complicated secondary structures. The standard set of 37 mitochondrial genes with a single control region is recognized in H. aotouensis as well as most other sequenced earwigs, whereas the addition or reduction of tRNA genes and control regions have also been reported in other earwigs [20].

The mitochondrial gene arrangement of H. aotouensis has apparently diverged from the ancestral pattern. The CREx analysis has been conducted for the earwig mitogenomes to predict the scenarios of rearrangement from the ancestral mitogenome type of D. yakuba. The H. aotouensis mitogenomes are rearranged from the ancestral mitogenome order by an initial transposition of two tRNA genes, a subsequent reversal of two tRNA genes, and two final TDRL events concerning five tRNA genes. The mitochondrial gene order of A. feae changed from D. yakuba mainly by four steps of rearrangement events, including the insertion of an additional trnV, the transposition of trnE, the subsequent reverse transposition of trnN, and a final reversal of trnF (Figure S1). In D. flavicollis, the mitogenome comprises three reversal events and a final TDRL event (Figure S2). In C. fletcheri, the mitogenome underwent three transposition events, two reversal events, and a reverse transposition event (Figure S3). The mitogenome of E. arcanum includes four reversal events and a final TDRL event (Figure S4). Only in E. metallica and P. flavocapitatus, the gene order is identical to that of D. yakuba [20]. The predicted rearrangement scenarios of earwig mitogenomes, i.e., the number, type, and order of rearrangement events, are different between species that have different gene orders. The scenarios seldomly involve PCGs and cannot change their final arrangement. The multiple rearranged tRNA genes support the prediction of Chen (2022) [20] that extensive mitochondrial gene rearrangement events occur in other unsequenced earwigs and these rearrangements are restricted to tRNA genes.

The RSCU analysis confirms TTA (Leu) as the most frequently used codon, which is similar to most other earwigs [20]. The calculation of Ka/Ks ratios of PCGs reveals a slight difference in cox1, cox2, and nad6 between the two geographical samples of H. aotouensis, which is due to the presence of a synonymous mutation on the third position of a certain codon in each of the genes. However, the detailed mechanisms underlying these synonymous mutations is unclear. The Ka/Ks values in PCGs also suggests that the fastest evolving PCG is nd4l in H. aotouensis, instead of cox1, nad2, or nad5 as found in other earwigs [20]. Such difference indicates that the evolutionary rates of PCGs are not always consistent between different species. Therefore, an evaluation of evolutionary rates should be conducted before the selection of a single mitochondrial gene for population genetic and phylogenetic research of Dermaptera. The tRNA genes of H. aotouensis are the same in the two geographical samples and have identical anticodons with all other sequenced earwigs. However, the tRNA genes are apparently different in nucleotide sequence, size, and location between different species. In the tRNA genes of H. aotouensis, the shortened DHU arm of trnS1 and mismatched G-U base pairs are very common in other earwigs and other metazoans [17,20,48]. The dominance of G-U mismatching might be explained by the bond’s low free energy, which makes it stable and neutral-like [49,50]. The location of the two rRNA genes is identical among all sequenced earwigs but their lengths and nucleotide content are highly variable between species.

In the phylogenetic analyses, the amino acid dataset performed better than the nucleotide dataset by generating identical phylogenetic trees of Dermaptera using different methods. Different types of molecular characters are usually preferred at different taxonomic levels, i.e., the nucleotide dataset is better for phylogenetic reconstruction among closely related taxa, whereas the amino acid dataset performs better to infer deeper phylogenetic relationships [51,52]. The nucleotide dataset can also be used for deeper phylogenetic reconstruction when their saturated third codon positions are excluded [53]. The choice of character type (nucleotide or amino acid) and reconstruction methods (PB, BI, or ML) did not seriously affect the tree topologies of Dermaptera in this study. The addition of the first mitogenomic sequences for Haplodiplatyidae did not change the relationship between the other five families inferred by the most recent mitochondrial phylogenetic study of Chen (2022) [20]. However, the newly sequenced Haplodiplatyidae is herein recovered as the sister group of Anisolabididae instead of Diplatyidae [9]. This result is confusing because Anisolabididae is apparently morphologically diverse from neither Haplodiplatyidae nor Diplatyidae. Although the phylogenetic position of Anisolabididae is also unresolved in previous morphological and molecular studies, it is often grouped with Spongiphoridae or Labiduridae [54]. This confusing clade might be caused by the probable misidentification of Euborellia arcanum Matzke & Kočárek, 2015, in Song et al. (2016) [22]. Another possible cause is the inherent deficiency of using mitochondrial DNA without combination with nuclear markers for phylogenetic reconstructions, which has been proved in many other phylogenetic studies [55,56,57]. The basal position of Apachyidae as a sister group to other earwigs was supported in most trees of this study, which is consistent with the phylogenomic study of Wipfler et al. (2020) [54] using nuclear single-copy genes. Apachyidae is also commonly considered a basal lineage in previous studies due to the presence of many primitive characters [4,19,54,58]. Despite the problematic placement of Anisolabididae, the close relationship between Pygidicranidae and Diplatyidae is supported in all trees, which also agrees with the result of Wipfler et al. (2020) [54]. Forficulidae is widely accepted as the most advanced earwig family based on morphology, nuclear genes, and histones [10,19,54,58,59]. However, the mitogenomic data from this study did not support the most advanced position of Forficulidae. The confusing higher-level phylogeny of several clades in this study is mainly attributed to the low suitability of mitochondrial markers alone for deeper phylogenetic reconstruction [57] and the lack of data for many other families of Dermaptera. The investigation of Chen (2022) [20] and this study indeed finds some merit in using mitogenomic data in phylogenetic reconstruction of Dermaptera by recovering partially similar topology with previous studies using both morphological and molecular data. However, the lack of combination with nuclear markers makes mitogenomic data less informative for higher-level phylogeny of Dermaptera, even when the saturated mitochondrial genes and codon positions are excluded and multiple methods are used for the analysis. In addition, many families of Dermaptera have no available mitogenomes, and most families involved in the current mitochondrial phylogenetic analysis have only one sequenced species. The confusing placement of several families in the mitochondrial phylogenetic trees needs reexamination by sequencing more representatives for these families.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found the intraspecific mitogenomic variation and extensive gene rearrangement of an earwig species from China. However, very few attentions have been paid to improve our understanding of mitogenomic characters of the earwigs. The mitogenomic data is promising in solving the problems in the phylogeny of Dermaptera More comprehensive sampling and sequencing of mitogenomes in combination with nuclear markers in the future are expected to reconstruct a more robust phylogeny of Dermaptera.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology11060807/s1. Figure S1. Reconstruction of mitochondrial gene rearrangement scenarios in the evolution of Apachyus feae. Figure S2. Reconstruction of mitochondrial gene rearrangement scenarios in the evolution of Diplatys flavicollis. Figure S3. Reconstruction of mitochondrial gene rearrangement scenarios in the evolution of Challia fletcheri. Figure S4. Reconstruction of mitochondrial gene rearrangement scenarios in the evolution of Euborellia arcanum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-L.L. and X.L.; methodology, Y.-Y.L.; software, S.C.; formal analysis, Z.-T.C.; investigation, D.-Q.P.; data curation, Q.-D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-L.L. and Z.-T.C.; writing—review and editing, H.-L.L. and Z.-T.C.; supervision, X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in NCBI GenBank (Accession number: ON186792 and ON186793).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Infestation Regularity and Control Technology of Primary Pests on Characteristic Fruit of Sichuan Province (grant number 2021XKJS084) and Sichuan Fruit Innovation Team of National Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (grant number sccxtd-04).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Haas F. Biodiversity of Dermaptera. In: Foottit G.R., Adler P.H., editors. Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society. 1st ed. Volume II. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2018. pp. 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins H., Michael D.M., Haas F., Lesley S.D. Dermaptera Species File Online. [(accessed on 25 June 2021)]. Available online: http://dermaptera.speciesfile.org/HomePage/Dermaptera/HomePage.aspx.

- 3.Haas F., Gorb S.N., Wootton R.J. Elastic joints in dermapteran hind wings: Materials and wing folding. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2000;29:137–146. doi: 10.1016/S1467-8039(00)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas F., Kukalova-Peck J. Dermaptera hindwing structure and folding: New evidence for familial, ordinal and superordinal relationships within Neoptera (Insecta) Eur. J. Entomol. 2001;98:445–509. doi: 10.14411/eje.2001.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas F., Gorb S.N. Evolution of locomotory attachment pads in the Dermaptera (Insecta) Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2004;33:45–66. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki S., Kitamura M., Matsubayashi K. Matriphagy in the hump earwig, Anechura harmandi (Dermaptera: Forficulidae), increases the survival rates of the offspring. J. Ethol. 2005;23:211–213. doi: 10.1007/s10164-005-0145-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staerkle M., Koelliker M. Maternal food regurgitation to nymphs in earwigs (Forficula auricularia) Ethology. 2008;114:844–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01526.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hincks W.D., editor. A Systematic Monograph of the Dermaptera of the World Based on Material in the British Museum (Natural History). Part One, Pygidicranidae Subfamily Diplatyinae. Natural History Museum; London, UK: 1955. pp. 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel M.S., Huang D., Thomas J.C., Cai C. A new genus and species of pygidicranid earwigs from the Upper Cretaceous of southern Asia (Dermaptera: Pygidicranidae) Cretac. Res. 2017;69:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas F. The phylogeny of the Forficulina, a suborder of the Dermaptera. Syst. Entomol. 1995;20:85–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.1995.tb00085.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas F., Klass K.D. The basal phylogenetic relationships in the Dermaptera. In: Klass K.D., editor. Proceedings of the 1st Dresden Meeting on Insect Phylogeny: Phylogenetic Relationships within the Insect Orders; Dresden, Germany. 19–21 September 2003; Dresden, Germany: Entomologische Abhandlungen; 2003. pp. 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klass K.D. The female genitalic region in basal earwigs (Insecta: Dermaptera: Pygidicranidae s.l.) Entomol. Abh. 2003;61:173–225. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross A.J., Engel M.S. The first diplatyid earwig in Tertiary amber (Dermaptera: Diplatyidae): A new species from Miocene Mexican amber. Insect. Syst. Evol. 2013;44:157–166. doi: 10.1163/1876312X-44032096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava G.K. Studies on Oriental Dermaptera preseved in the B. P. Museum, Hawaii, U.S.A. Rec. Zool. Surv. India Occas. Pap. 2003;210:1–72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma W.Z., Chen Y.X. The Diplatyidae of China (Dermaptera) Sinozoologoa. 1991;8:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y.X., Ma W.Z., editors. Fauna Sinica, Insecta. Volume 35. Science Press; Beijing, UK: 2004. pp. 1–420. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan X., Kim M.I., Kim M.J., Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genome of the free-living earwig, Challia fletcheri (Dermaptera: Pygidicranidae) and phylogeny of Polyneoptera. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beutel R., Wipfler B., Gottardo M., Dallai R. Polyneoptera or “Lower Neoptera”-New light on old and difficult phylogenetic problems. Atti Accad. Naz. Ital. Entomol. 2013;61:113–142. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naegle M.A., Mugleston J.D., Bybee S.M., Whiting M.F. Reassessing the phylogenetic position of the epizoic earwigs (Insecta: Dermaptera) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016;100:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Z.T. Comparative mitogenomic analysis of two earwigs (Insecta, Dermaptera) and the preliminary phylogenetic implications. ZooKeys. 2022;1087:105–122. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.1087.78998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron S.L. Insect mitochondrial genomics: Implications for evolution and phylogeny. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014;59:95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song N., Li H., Song F., Cai W. Molecular phylogeny of Polyneoptera (Insecta) inferred from expanded mitogenomic data. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:36175. doi: 10.1038/srep36175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K., Ding S., Yang D. The complete mitochondrial genome of a stonefly species, Kamimuria chungnanshana Wu, 1948 (Plecoptera: Perlidae) Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2016;27:3810–3811. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1082088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin J.J., Yu W.B., Yang J.B., Song Y., Depamphilis C.W., Yi T.S., Li D.Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020;21:241. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernt M., Donath A., Jühling F., Externbrink F., Florentz C., Fritzsch G., Pütz J., Middendorf M., Stadler P.F. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013;69:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant J.R., Stothard P. The CGView server: A comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:181–184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perna N.T., Kocher T.D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;41:353–358. doi: 10.1007/BF01215182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernt M. CREx: Inferring genomic rearrangements using common intervals. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2957–2958. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burla H. Zur Kenntnis der Drosophiliden der Elfenbeinkuste (Franzosisch West-Afrika) Rev. Suisse Zool. 1954;61:1–218. doi: 10.5962/bhl.part.75413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clary D.O., Wolstenholme D.R. The ribosomal RNA genes of Drosophila mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:4029–4045. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.11.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Zhu J., Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Broteom. Bioinform. 2010;8:77–80. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia X. DAMBE5: A comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;35:1550–1552. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaidya G., Lohman D.J., Meier R. SequenceMatrix: Concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics. 2011;27:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanfear R., Frandsen P.B., Wright A.M., Senfeld T., Calcott B. PartitionFinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;34:772–773. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lartillot N., Lepage T., Blanquart S. PhyloBayes 3: A Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2286–2288. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and postanalysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rand D.M., Kann L.M. Mutation and selection at silent and replacement sites in the evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA. Genetica. 1998;102/103:393–407. doi: 10.1023/A:1017006118852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei L., He J., Jia X., Qi Q., Liang Z., Zheng H., Ping Y., Liu S., Sun J. Analysis of codon usage bias of mitochondrial genome in Bombyx moriand its relation to evolution. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014;14:262. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0262-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fauron C.M.R., Wolstenholme D.R. Extensive diversity among Drosophila species with respect to nucleotide sequences within the adenine+thymine-rich region of mitochondrial DNA molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:2439–2452. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.11.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inohira K., Hara T., Matsuura E.T. Nucleotide sequence divergence in the A+T-rich region of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila simulans and Drosophila mauritiana. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1997;14:814–822. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burr M. Observations on the Dermatoptera, including revisions of several genera, and descriptions of new genera and species. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 1904;5:277–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.1904.tb02747.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bormans A.D.E. Viaggio di Leonardo Fea in Birmaniae regioni vicne. LXI. Dermapters (2nd Partie) Anna. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Giacomo Doria. 1894;14:371–409. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garey J.R., Wolstenholme D.R. Platyhelminth mitochondrial DNA: Evidence for early evolutionary origin of a tRNAserAGN that contains a dihydrouridine arm replacement loop, and of serine-specifying AGA and AGG codons. J. Mol. Evol. 1989;28:374–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02603072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aboul-Ela F., Koh D., Tinoco I., Jr., Martin F.H. Base-base mismatches. Thermodynamics of double helix formation for dCA3XA3G+ dCT3YT3G (X, Y = A, C, G, D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:4811–4824. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.13.4811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erdmann V.A., Wolters J., Huysmans E., De Wachter R. Collection of published 5S, 5.8s and 4.5s ribosomal RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:105–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.suppl.r105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simmons M.P., Ochoterena H., Freudenstein J.V. Amino acid vs. nucleotide characters: Challenging preconceived notions. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2002;24:78–90. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simmons M.P., Carr T.G., O’Neill K. Relative character-state space, amount of potential phylogenetic information, and heterogeneity of nucleotide and amino acid characters. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;32:913–926. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Regier J.C., Shultz J.W. Elongation factor-2: A useful gene for arthropod phylogenetics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2001;20:136–148. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wipfler B., Koehler W., Frandsen P.B., Donath A., Liu S., Machida R., Misof B., Peters R.S., Shimizu S., Zhou X., et al. Phylogenomics changes our understanding about earwig evolution. Syst. Entomol. 2020;45:516–526. doi: 10.1111/syen.12420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flook P.K., Klee S., Rowell C.H.F. Combined molecular phylogenetic analysis of the Orthoptera (Arthropoda, Insecta) and implications for their higher systematics. Syst. Biol. 1999;48:233–253. doi: 10.1080/106351599260274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castro L.R., Dowton M. The position of the Hymenoptera within the Holometabola as inferred from the mitochondrial genome of Perga condei (Hymenoptera: Symphyta: Pergidae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2005;34:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Galtier N., Nabholz B., Glémin S., Hurst G.D.D. Mitochondrial DNA as a marker of molecular diversity: A reappraisal. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:4541–4550. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kocarek P., John V., Hulva P. When the body hides the ancestry: Phylogeny of morphologically modified epizoic earwigs based on molecular evidence. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jarvis K.J., Haas F., Whiting M.F. Phylogeny of earwigs (Insecta: Dermaptera) based on molecular and morphological evidence: Reconsidering the classification of Dermaptera. Syst. Entomol. 2005;30:442–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2004.00276.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in NCBI GenBank (Accession number: ON186792 and ON186793).