Abstract

We examined 233 silage samples and found that molds were present in 206 samples with counts between 1 × 103 and 8.9 × 107 (mean, 4.7 × 106) CFU/g. Mycophenolic acid, a metabolite of Penicillium roqueforti, was detected by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in 74 (32%) of these samples at levels ranging from 20 to 35,000 (mean, 1,400) μg/kg. This compound has well-known immunosuppressive properties, so feeding with contaminated silage may promote the development of infectious diseases in livestock.

Silage is frequently contaminated with fungi of the genera Monascus, Aspergillus, and Penicillium (14). One of the most common molds is Penicillium roqueforti, which can produce secondary metabolites such as roquefortine C, isofumiclavines A and B, PR toxin, macrofortines, and mycophenolic acid (5, 6, 10, 13). Roquefortine C has been detected frequently in silage (3, 11, 16), but little is known about the natural occurrence of the other mycotoxins, especially mycophenolic acid.

Mycophenolic acid [6-(4-hydroxy-6-methoxy-7-methyl-3- oxo-5-phthalanyl)-4-methyl-4-hexenoic acid] is a weak organic acid with antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral activities (1, 2, 5). Its acute toxicity to mammals seems to be low: the calculated oral 50% lethal doses for rats and mice are 700 and 2,500 mg/kg, respectively (6). Mycophenolic acid is also a noncompetitive inhibitor of eukaryotic inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (12) and blocks the conversion of inosine-5-phosphate and xanthine-5-phosphate to guanosine-5-phosphate. As T and B lymphocytes rely primarily on the de novo biosynthesis of purine rather than on the purine salvage pathway, mycophenolic acid blocks their proliferative response and inhibits both antibody formation and the production of cytotoxic T cells (9).

Consumption of immunosuppressive compounds increases the risk of infectious diseases in livestock, but this risk cannot be accurately estimated without knowledge of naturally occurring immunosuppressants such as mycophenolic acid in silage. Therefore, we analyzed samples of grass and maize silage for the presence of P. roqueforti and mycophenolic acid.

Samples.

Samples of grass (n = 98) and maize (n = 135) silage partly visibly contaminated with molds were collected in Bavaria during 1997 and 1998. The mycobiota of the samples was determined quantitatively and qualitatively, and an aliquot of each silage type (∼500 g) was stored at −18°C until the analysis of mycophenolic acid.

Mycological examination.

An aliquot of 10 g of mechanically minced silage was suspended in 90 ml of sterile peptone water (10 g of casein peptone [Merck, Darmstadt, Germany], 8.5 g of sodium chloride [Merck], 1,000 ml of distilled water) and shaken at 20°C for 30 min. From this initial dilution (10−1), subsequent dilutions (1:10) were made in sterile peptone water. For mold count determinations, 0.1-ml aliquots from the dilutions (10−2 to 10−4) were plated on Sabouraud 2% dextrose agar (Merck) supplemented with 400,000 IU of penicillin G (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) and 40 mg of streptomycin (Sigma) per liter and on DG18 agar (antibiotic-free dichloran–18% glycerol agar base; Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) supplemented with 200 g of glycerol (Merck) per liter and 20 mg of chlortetracycline (Sigma) per liter. The plates were incubated at 20°C for at least 14 days. Dominant fungal genera and species were identified by macroscopic and microscopic criteria (7, 15).

Chemicals used for mycotoxin analysis.

Mycophenolic acid was purchased from Sigma and used without further purification. All of the solvents used for extraction, cleanup, and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) were analytical grade. High-performance liquid chromatography quality water was prepared using a Millipore Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany). Silica gel 60 and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) were obtained from Merck.

Extraction procedures.

A 50-g portion of a well-mixed sample was placed in a 500-ml Erlenmeyer flask with 250 ml of chloroform. The flask was stoppered with a screw cap and shaken on a wrist action shaker for 60 min before filtering of the sample through fluted filter paper (595 1/2; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). An aliquot of 20 ml (equivalent to 4 g of silage) was transferred to a 100-ml round-bottom flask and evaporated to near dryness by rotary evaporation at 35°C.

Cleanup column preparation.

Five milliliters of n-hexane was added to a glass column (10 mm [inside diameter] by 300 mm [length] with 35-μm-pore-size porous polypropylene frit and a nylon stopcock), and 0.5 g of anhydrous Na2SO4 was added. One gram of silica gel 60 was slurried with 10 ml of hexane in a 15-ml beaker and poured into the column. The beaker was washed twice with 5 ml of solvent to effect transfer. After the gel settled, it was topped with 1 g of anhydrous Na2SO4 and the solvent was drained to the top of the Na2SO4 layer.

Cleanup chromatography.

The extract was dissolved in 1 ml of chloroform and transferred to the silica column. The column was washed with 10 ml of hexane–10 ml of toluene–10 ml of toluene-acetone (9.48:0.52, vol/vol); mycophenolic acid was eluted with 40 ml of toluene-acetone-98% acetic acid (30:8:2, vol/vol/vol) into a 100-ml round-bottom flask. The eluate was evaporated to dryness by rotary evaporation at 35°C, and the residue was redissolved in 1 ml of methanol.

LC-MS.

The LC-MS system used consisted of a high-performance liquid chromatography pump (2248; Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden), a Nucleosil C18 column (125 by 3 mm [inside diameter], 3 μm [Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany], ambient temperature), and a quadrupole mass spectrometer (VG Platform 2; Fisons Instruments, Manchester, United Kingdom) equipped with an electrospray ionization source and a MassLynx data system (Fisons Instruments). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile-water-100% formic acid (99:99:2, vol/vol/vol). The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, so postcolumn splitting was arranged to achieve a flow of 20 μl/min to the source. A 10-μl volume of a sample or a standard solution was injected onto the column, and the eluent was monitored either in full scan mode (m/z 100 to 400) or by selected-ion recording. Identification of mycophenolic acid in spiked and native samples was based on the retention time and relative peak area of four selected ions (m/z 321 [M+H]+, 303, 275, 207); in addition, the m/z 343 (M+Na)+ and 359 (M+K)+ ions were monitored. For quantification, the area of the base peak (m/z 303) was compared to that of an external standard.

Validation of analysis.

Samples of grass and maize silage were spiked with mycophenolic acid to obtain concentrations of 5 to 500 μg/kg; unspiked silage samples were used as controls. The samples were analyzed, and the recovery rates were calculated.

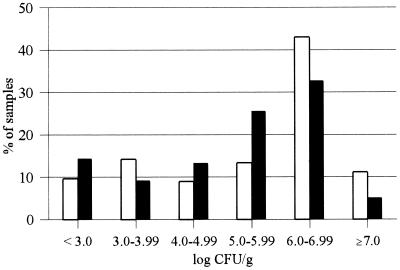

Examination of the mold flora of 233 silage samples showed that 88% of the samples contained more than 103 CFU/g; in most (64%) of the samples, more than 105 CFU/g were recovered (Fig. 1). A variety of molds were isolated, especially species of the families dematiaceous Hyphomycetes (n = 34) and Mucoraceae (n = 57), as well as representatives of the genera Aspergillus (n = 35), Penicillium (n = 123), Monascus (n = 43), and Scopulariopsis (n = 16). P. roqueforti was the dominant mold; 70 (30%) samples were contaminated with this species; Aspergillus fumigatus (9% of samples positive) and Monascus ruber (19% of samples positive) were isolated less frequently.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of mold counts in maize silage (□; n = 135) and grass silage (■; n = 98).

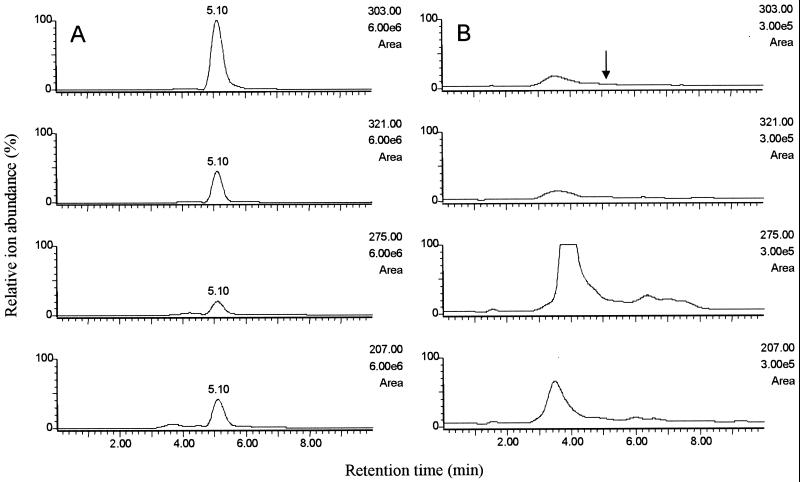

The LC-MS method employed for mycophenolic acid analysis was reliable and linear in a range of 25 to 500 μg/kg. The detection limit was 20 μg/kg (signal-to-noise ratio, 5:1). The selected ion chromatograms of unspiked silage had background components from the matrix, but at the retention time of mycophenolic acid (5.1 min), no interfering ions (m/z 207, 275, 303, 321) were detected (Fig. 2). The mean recovery of mycophenolic acid was 85% in maize silage and 86% in grass silage.

FIG. 2.

LC-MS selected-ion chromatograms of grass silage naturally contaminated with mycophenolic acid (A, 4,100 μg/kg) and a blank sample (B, magnified 20-fold).

Mycophenolic acid was present in 74 (32%) of 233 samples at levels ranging from 20 to 35,000 μg/kg (Table 1). Simultaneous detection of mycophenolic acid and P. roqueforti was possible in only 32 samples, and there was no correlation between the fungal counts of P. roqueforti and the concentration of mycophenolic acid (data not shown). These results can be explained by the fact that different subsamples were used for mycological investigations and mycotoxin analysis. Moreover, not all strains of P. roqueforti produce mycophenolic acid (4) and positive strains produce different amounts under standardized conditions (8). In addition, the CFU counts obtained by dilution plating are related only to the presence of viable conidia and not necessarily to the ability to produce mycophenolic acid. Our results demonstrate that mycophenolic acid occurs frequently in silage. Considering that cattle eat up to 25 kg of silage per day, a dose of 1.8 mg of mycophenolic acid per kg of body weight results. This amount is equivalent to 10% of the dose used to suppress graft rejection in humans. Further study is required to determine if the levels found in silage are high enough to induce immunosuppression in farm animals, resulting in a higher incidence of infectious diseases.

TABLE 1.

Occurrence of mycophenolic acid in maize and grass silage

| Type of silage | No. of samples analyzed

|

Mean (range) concn (μg/kg) of mycophenolic acid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positive | ||

| Maize | 135 | 38 | 690 (20–23,000) |

| Grass | 98 | 36 | 2,200 (21–35,000) |

| Total | 233 | 74 | 1,400 (20–35,000) |

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham E P. The effect of mycophenolic acid on the growth of Staphylococcus aureus in heart broth. Biochem J. 1945;39:398–404. doi: 10.1042/bj0390398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams R, Bently M. Biosynthesis of nucleic acid purines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959;79:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auerbach H, Oldenburg E, Weissbach F. Incidence of Penicillium roqueforti and roquefortine C in silages. J Sci Food Agric. 1998;76:565–572. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boysen M, Skouboe P, Frisvad J, Rossen L. Reclassification of Penicillium roqueforti group into three species on the basis of molecular genetic and biochemical profiles. Microbiology. 1996;142:541–549. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-3-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cline J C, Nelson J D, Gerzon K, Williams R H, Delong D C. In vitro antiviral activity of mycophenolic acid and its reversal by guanine compounds. Appl Microbiol. 1969;18:14–20. doi: 10.1128/am.18.1.14-20.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole R J, Cox R H. Handbook of toxic fungal metabolites. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domsch K H, Gams W. Compendium of soil fungi. Eching, Germany: IHW-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel G, von Milczewski E E, Prokopek D, Teuber M. Strain-specific synthesis of mycophenolic acid by P. roqueforti in blue-veined cheese. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:1034–1040. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.5.1034-1040.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eugui A M, Almquist S, Muller C D, Allison A C. Lymphocyte-selective cytostatic and immunosuppressive effects of mycophenolic acid in vitro: role of deoxyguanoside nucleotide depletion. Scand J Immunol. 1991;33:161–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb03746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisvad J C, Thrane U. Mycotoxin production by food-borne fungi. In: Samson R A, Hoekstra E S, Frisvad J C, Filtenborg O, editors. Introduction to food-borne fungi. Baarn, The Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures; 1996. pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Häggblom P. Isolation of roquefortine C from feed grain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2924–2926. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2924-2926.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H J, Pawlak K, Nguyen B T, Robins R K, Sadee W. Biochemical differences among four inosinate dehydrogenase inhibitors, mycophenolic acid, ribavirin, tiazofurin, and selenazofurin, studied in mouse lymphoma cell culture. Cancer Res. 1985;45:5512–5520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nout M J R, Bouwmeester H M, Haaksma J, van Dyke H. Fungal growth in silages of sugarbeet press pulp and maize. J Agric Sci. 1993;121:323–326. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelhate J. Maize silage: incidence of moulds during conservation. Folia Vet Lat. 1977;7:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samson R A, Hoekstra E S, Frisvad J C, Filtenborg O. Introduction to food-borne fungi. Baarn, The Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tüller G, Armbruster G, Wiedenmann S, Hänichen T, Schams D, Bauer J. Occurrence of roquefortine in silage—toxicological relevance to sheep. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 1998;80:246–249. [Google Scholar]