Abstract

Background and Objective: Small, dense low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) are considered more atherogenic than normal size LDLs. However, the measurement of small, dense LDLs requires sophisticated laboratory methods, such as ultracentrifugation, gradient gel electrophoresis, or nuclear magnetic resonance. We aimed to analyze whether the LDL apolipoprotein B (LDLapoB)-to-LDL cholesterol (LDLC) ratio is associated with cardiovascular mortality and whether this ratio represents a biomarker for small, dense LDLs. Methods: LDLC and LDLapoB were measured (beta-quantification) and calculated (according to Friedewald and Baca, respectively) for 3291 participants of the LURIC Study, with a median (inter-quartile range) follow-up for cardiovascular mortality of 9.9 (8.7–10.7) years. An independent replication cohort included 1660 participants. Associations of the LDLapoB/LDLC ratio with LDL subclass particle concentrations (ultracentrifugation) were tested for 282 participants. Results: In the LURIC Study, the mean (standard deviation) LDLC and LDLapoB concentrations were 117 (34) and 85 (22) mg/dL, respectively; 621 cardiovascular deaths occurred. Elevated LDLapoB/LDLC (calculated and measured) ratios were significantly and independently associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in the entire cohort (fourth vs. first quartile: hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) = 2.07 (1.53–2.79)) and in statin-naïve patients. The association between calculated LDLapoB/LDLC ratio and cardiovascular mortality was replicated in an independent cohort. High LDLapoB/LDLC ratios were associated with higher LDL5 and LDL6 concentrations (both p < 0.001), but not with concentrations of larger LDLs. Conclusions: Elevated measured and calculated LDLapoB/LDLC ratios are associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. Use of LDLapoB/LDLC ratios allows estimation of the atherogenic risk conferred by small, dense LDLs.

Keywords: apolipoprotein B; cardiovascular mortality; cholesterol; small, dense LDLs

1. Introduction

The intimal penetration and retention of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) represents a key step in the pathophysiological process of atherogenesis [1]. Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDLC) is considered to reflect the magnitude of this process [1]. Consistently, high LDLC is associated with increased cardiovascular risk [2]; on the other hand, therapeutic lowering of LDLC reduces this risk [3]. Therefore, LDLC is frequently employed in guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias, as typified and endorsed by the European Society of Cardiology/European Atherosclerosis Society [4], the American College of Cardiology, and the American Heart Association [5]. Not only the circulating concentration of LDLs, but also the chemical composition and the subclass particle profile has an impact on LDL atherogenicity [1]. In this respect, elevated concentrations of small, dense LDLs are associated with increased cardiovascular risk [1,6,7,8]. Quantifying small, dense LDLs, however, requires sophisticated and laborious laboratory methods, potentially involving their ultracentrifugal isolation, or indirect determination by gradient gel electrophoresis or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy [9].

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is a direct measure of the particle concentration of all atherogenic lipoproteins, including LDLs, Lp(a), and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants, but does not differentiate between LDLs and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) [9]. Baca and Warnick have proposed a method for the estimation of LDL apolipoprotein B (LDLapoB) from total apoB [10]. Although LDLapoB represents the concentration of atherogenic LDL particles in all subclasses, it does not differentiate between small, dense LDL particles and larger and lighter subclasses. Our working hypothesis was that an elevated ratio of LDLapoB to LDLC (LDLapoB/LDLC) would be associated with increased cardiovascular risk and that this ratio may be a measure of the concentration of small, dense LDLs.

Therefore, the aim of the present work was to explore the relationship between LDLapoB/LDLC ratios, both measured (LDLapoB/LDLCmeas) and calculated (LDLapoB/LDLCcalc), and cardiovascular mortality in participants of the prospective Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health (LURIC) Study (11–13) and to replicate findings in an independent cohort (LDLapoB/LDLCcalc). Subsequently, it was intended that the question of whether the LDLapoB/LDLC ratio might represent a biomarker for small, dense LDL particles would be examined.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design, Participants, and Clinical Characterization of the LURIC Cohort

A total of 3316 patients who were referred for coronary angiography to the Ludwigshafen Heart Center in Southwest Germany, were recruited between July 1997 and January 2000 [11,12,13]. Inclusion criteria were: German ancestry, clinical stability except for acute coronary syndromes, and the availability of a coronary angiogram. Indications for angiography in individuals with clinically stable disease were chest pain and/or noninvasive test results suggestive of myocardial ischemia. Individuals suffering from any acute illness other than acute coronary syndromes, chronic non-cardiac diseases, or malignancy within the five past years, and those unable to understand the purpose of the study were excluded [11,12,13]. Subjects with missing data were also ruled out, resulting in a subgroup of 3291 participants for the present analysis. Coronary artery disease was diagnosed by angiography. Acute myocardial infarction was defined as a myocardial infarction that had occurred within four weeks prior to enrolment. ST-elevation myocardial infarction was diagnosed if typical electrocardiogram changes were present along with prolonged chest pain refractory to sublingual nitrates and/or enzyme or troponin T elevations. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction was diagnosed, if symptoms and troponin T criteria, but not the electrocardiogram criteria for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, were met. The functional capacity of patients with cardiac disease, especially heart failure, was estimated according to a classification developed by the New York Heart Association. Left ventricular function was estimated using echocardiography [11]. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed according to the current guidelines of the American Diabetes Association [14]. Hypertension was diagnosed when the systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure exceeded 140 and/or 90 mmHg or if there was a history of hypertension, evident from treatment with antihypertensive drugs [11].

2.2. Follow-Up of the LURIC Cohort

Information on the vital status was obtained from local population registries. Cardiovascular mortality was defined as death due to fatal myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death, death after cardiovascular intervention, stroke, or other causes of death due to cardiovascular diseases. An assessment of death certificates was carried out by two experienced clinicians. In a few cases of disagreement or uncertainty concerning the coding of a specific cause of death, classification was made by a principal investigator of the LURIC study [12,13]. The median (interquartile range) duration of follow-up was 9.9 (8.7–10.7) years (mean and standard deviation: 8.8 (3.0)).

2.3. Replication Cohort

The replication cohort included 1660 Caucasian patients, of whom 20 were lost during follow-up. They were referred to elective coronary angiography for the evaluation of established or suspected stable coronary artery disease at the academic teaching hospital Feldkirch, a tertiary care centre in Western Austria between 1999 and 2008 [15]. Coronary artery disease was diagnosed by coronary angiography. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed according to the current guidelines of the American Diabetes Association [14]. Hypertension was defined according to the 2013 European Atherosclerosis Society/European Society of Hypertension guidelines [16]. There was a follow-up for cardiovascular mortality with a median (interquartile range) duration of 10.9 (7.7–12.1) years. Time and causes of death were obtained from a national survey (Statistik Austria, Vienna, Austria) or from hospital records.

2.4. Cohorts for Evaluation of LDL Subfractions

We report on data from 282 subjects from 3 studies [17,18,19]. The first study included samples from 106 persons with increased risk for type 2 diabetes or newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes not yet receiving oral antidiabetics, insulin, or lipid-lowering agents. The samples were taken as part of the baseline screening examination for a randomized controlled statin trial [17]. The second study included samples from 77 patients with coronary heart disease or high cardiovascular risk with well-controlled LDLC concentrations. The samples were taken as part of the baseline examination of a randomized controlled trial of a combination treatment of statin and ezetimibe versus statin treatment alone [18]. The third study included samples from 99 patients with type 2 diabetes. The samples were taken as part of the baseline examination of a dietary intervention study comparing a low-carbohydrate diet with a standard diet [19].

2.5. Laboratory Analyses

2.5.1. Standard Measurements

All analyses were performed using fasting blood samples. In the LURIC cohort, lipoproteins were separated using a combined ultracentrifugation–precipitation method (β-quantification). The VLDL fraction (d < 1.006 g/mL) was recovered by ultracentrifugation (18 h, 10 °C, 30,000 rpm). ApoB-containing lipoproteins in the resulting bottom fraction were precipitated using phosphotungstic acid, with the HDL particles remaining in solution. LDLapob and LDLC were then derived from the substraction of apoB and cholesterol after precipitation from their respective concentrations before precipitation. LDLC was calculated according to Friedewald et al. (LDLC = total cholesterol − HDL cholesterol − triglycerides/5) [20], and LDLapoB was calculated according to Baca and Warnick (LDLapoB = apoB − 10 − triglycerides/32; validated for subjects with triglycerides < 400 mg/dL) [10]. Cholesterol and triglycerides were measured with enzymatic reagents from WAKO (Neuss, Germany) using a WAKO 30 R analyzer. ApoB was measured by turbidimetry (Rolf-Greiner Biochemica, Flacht, Germany). LDL particle diameter was calculated as previously described [21]. C-reactive protein was measured was measured by immunonephelometry on a Behring Nephelometer II (N High Sensitivity CRP, Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany). Glucose was measured with an enzymatic assay on a Hitachi 717 analyzer.

In the replication cohort, serum levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDLC, and HDL cholesterol were measured using enzymatic hydrolysis and precipitation techniques (triglycerides GPO-PAP, CHOD/PAP, QuantolipLDL, QuantolipHDL; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with a Hitachi-Analyzer 717 or 911. Serum apolipoprotein B was determined on a Cobas Integra 800® (Roche).

2.5.2. Equilibrium Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation of LDL Subfractions

Lipoproteins were isolated by sequential preparative ultracentrifugation using the following densities: d < 1.006 kg/L for VLDL, 1.006 < d < 1.019 kg/L for intermediate density lipoproteins, 1.019 < d < 1.063 kg/L for LDL, and 1.063 < d < 1.21 kg/L for HDL. The subfractions of LDLs were separated according to Baumstark et al. into 6 density classes by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation. The density ranges of LDL subfractions were: LDL1, <1.031 kg/L; LDL2, 1.031–1.034 kg/L; LDL3, 1.034–1.037 kg/L; LDL4, 1.037–1.040 kg/L; LDL5, 1.040–1.044 kg/L; LDL6, >1.044 kg/L [22]. The LDL5 and LDL6 fractions were considered small, dense LDLs.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Quartiles of the LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc ratios were formed. Baseline characteristics of the LURIC cohort are presented according to quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc, in the entire cohort, in statin-naïve patients, and in patients on statins. The χ2-test and Analysis of Variance were used to compare the distributions of variables across the quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc ratios. Triglycerides and C-reactive protein were transformed logarithmically before being used in parametric statistical models. Pearson correlation was calculated for the relationship between LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc and this relationship was also illustrated using a box and scatter plot. The association of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles with the risk of cardiovascular death in the entire LURIC cohort was examined with Kaplan–Meier curves and with the log-rank test. Cox regression was used to examine the association of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc quartiles with time to endpoints in the entire LURIC cohort, in statin-naïve patients and in patients on statins using 2 predefined models of adjustment: Model 1 included the covariates sex, age, statin use, and the interaction term between statin use and the LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc quartiles. Model 2 additionally included body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. The analyses in the replication cohort were pre-specified and in accordance with the LURIC study. ANOVA was used to compare the distributions of apoB in LDL subclasses across the quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc in the combined cohort with LDL density gradient ultracentrifugation. All statistical tests were 2-sided and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. The SPSS 26 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

2.7. Ethical Aspects

The LURIC study was approved by the ethics committee of the Physicians Chamber of Rheinland-Pfalz. The replication cohort and the 3 studies, in which LDL subfractions were measured using density gradient ultracentrifugation, were also approved by local ethics committees. All studies were performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, and all participants gave written informed consent [11,12,13,16,17,18,19].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the LURIC and Replication Cohorts

The mean (standard deviation) age of the 3291 LURIC participants (2294 males, 997 females) was 62.6 (10.6) years. Participants displayed a mean body mass index of 27.5 (4.1) kg/m2 and total and LDLC levels of 192 (39) and 117 (34) mg/dL, respectively. Mean total and LDLapoB values were 104 (25) and 85 (22) mg/dL, respectively. The mean (standard deviation) ratio of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas was 0.74 (0.09). Higher LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles were positively associated with male sex, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and smoking. Age was inversely related to the quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas. Total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and LDL diameter were inversely related to quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas. Total apoB and LDL triglyceride levels were positively related to the quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas. Coronary artery disease, impaired left ventricular function, and peripheral artery disease were more prevalent in patients with elevated LDLapoB/LDLCmeas ratios. Statin use was more frequent in patients with high LDLapoB/LDLCmeas (Table 1). The baseline characteristics according to the quartiles of the LDLapoB/LDLCmeas ratio stratified for statin treatment are shown in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Consistent results were obtained for LDLapoB/LDLCcalc ratios (Supplementary Tables S3–S5). The baseline characteristics of the replication cohort were similar to the LURIC study (Supplementary Table S6).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles in the entire LURIC cohort.

| 1st Quartile | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 836 | 810 | 821 | 824 | - |

| Male sex | 456 (54.5) | 570 (70.4) | 629 (76.6) | 639 (77.5) | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 63.3 (10.8) | 63.2 (10.6) | 62.6 (10.4) | 61.4 (10.6) | 0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.7 (3.9) | 27 (3.8) | 27.9 (4.2) | 28.4 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 572 (68.4) | 588 (72.6) | 602 (73.3) | 629 (76.3) | 0.004 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 396 (47.4) | 287 (35.4) | 269 (32.8) | 234 (28.4) | |

| Former | 302 (36.1) | 367 (45.3) | 372 (45.3) | 414 (50.2) | |

| Current | 138 (16.5) | 156 (19.3) | 180 (21.9) | 176 (21.4) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 248 (29.7) | 284 (35.1) | 365 (44.5) | 414 (50.2) | <0.001 |

| Lipids | |||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL † | 207 (39) | 192 (34) | 187 (37) | 182 (42) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL † | 135 (37) | 121 (29) | 114 (30) | 95.5 (29) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL † | 45.5 (11.5) | 41 (10) | 36 (9) | 32 (8) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL ‡ | 119 (45) | 140 (55) | 170 (64) | 264 (184) | <0.001 § |

| LDL triglycerides, mg/dL ‡ | 29 (10) | 30 (10) | 33 (12) | 34 (14) | <0.001 § |

| ApoB, mg/dL | 102 (25) | 103 (23) | 106 (25) | 107 (26) | <0.001 |

| LDL apo B, mg/dL | 87 (23) | 86 (20) | 86 (22) | 81(23) | <0.001 |

| LDL apolipoprotein B-to-LDL cholesterol ratio | 0.65 (0.03) | 0.71 (0.01) | 0.76 (0.02) | 0.86 (0.10) | - |

| LDL diameter, nm | 17.0 (0.4) | 16.6 (0.3) | 16.5 (0.3) | 16.2 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 6.1 (13.5) | 8.1 (15.3) | 10.8 (20.9) | 11.3 (21.1) | <0.001 § |

| Coronary artery disease || | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 289 (35) | 189 (23.4) | 127 (16.2) | 128 (16.2) | |

| Stable angina | 372 (45.1) | 388 (49.0) | 393 (50.1) | 378 (47.7) | |

| ACS | 164 (19.9) | 215 (27.1) | 265 (33.8) | 286 (36.1) | |

| NYHA functional class | 0.131 | ||||

| I | 432 (51.7) | 426 (52.6) | 437 (53.2) | 415 (50.4) | |

| II | 265 (31.7) | 233 (28.8) | 229 (27.9) | 235 (28.5) | |

| III | 126 (15.1) | 125 (15.4) | 124 (15.1) | 146 (17.7) | |

| IV | 13 (1.6) | 26 (3.2) | 31 (3.8) | 28 (3.4) | |

| Left ventricular function # | <0.001 | ||||

| Normal | 566 (70.8) | 502 (64.2) | 447 (56.4) | 454 (57.2) | |

| Mildly impaired | 99 (12.4) | 113 (14.5) | 126 (15.9) | 122 (15.4) | |

| Moderately impaired | 62 (7.8) | 83 (10.6) | 103 (13) | 102 (12.8) | |

| Severely impaired | 23 (2.9) | 36 (4.6) | 44 (5.5) | 41 (5.2) | |

| Friesinger score | <0.001 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 282 (33.7) | 176 (21.7) | 121 (14.7) | 135 (16.4) | |

| 2nd quartile | 223 (26.7) | 182 (22.5) | 168 (20.5) | 168 (20.4) | |

| 3rd quartile | 202 (24.2) | 261 (32.2) | 304 (37) | 295 (35.8) | |

| 4th quartile | 129 (15.4) | 191 (23.6) | 228 (27.8) | 226 (27.4) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 49 (5.9) | 77 (9.5) | 82 (10) | 101 (12.3) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 74 (8.9) | 62 (7.7) | 86 (10.5) | 77 (9.3) | 0.256 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | |||||

| Statin | 231 (27.6) | 337 (41.6) | 472 (57.5) | 503 (61) | <0.001 |

| Non-statin lipid-lowering drugs | 17 (2) | 21 (2.6) | 15 (1.8) | 26 (3.2) | 0.288 |

Legend: Values are means ± standard deviations or medians (25th–75th percentiles) in cases of continuous variables and numbers (percentages) in cases of categorical data. * For differences across the four groups calculated with the χ2 test and Analysis of Variance for categorical and continuous data, respectively. † To convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.02586. ‡ To convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.01129. § Analysis Of Variance of logarithmically transformed values. || 825/792/785/792. # 750/734/720/719.

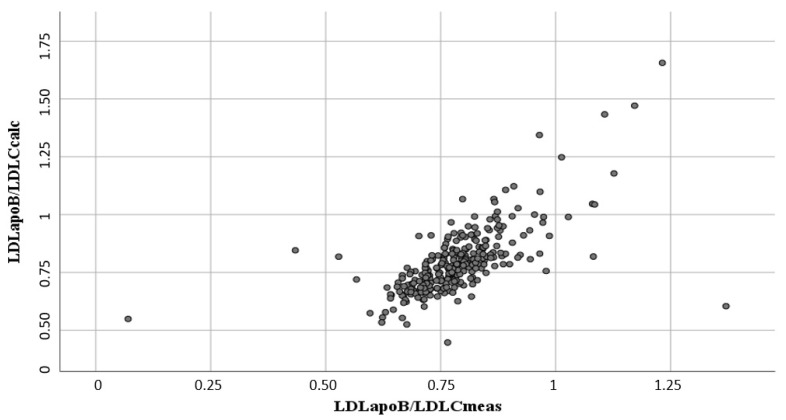

3.2. Comparison of Measured and Calculated LDLC and LDLapoB

The mean measured LDLC and LDLapoB concentrations for patients with triglyceride levels of <400 mg/dL were 118 (34) and 85 (22) mg/dL, respectively. In the same subgroup, the LDLC and LDLapoB concentrations, calculated according to Friedewald et al. [20] and Baca et al. [10], respectively, were 121 (34) and 89 (24) mg/dL, respectively. The correlations between the measured and calculated LDLC and LDLapoB concentrations were r = 0.90, p < 0.001 and r = 0.91, p < 0.001, respectively. The correlation between LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc (LDLapoB/LDLCcalc = 0.132 + 0.842 × LDLapoB/LDLCmeas) was r = 0.73, p < 0.001 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Association between LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc in the LURIC cohort. Legend: for each patient one grey circle.

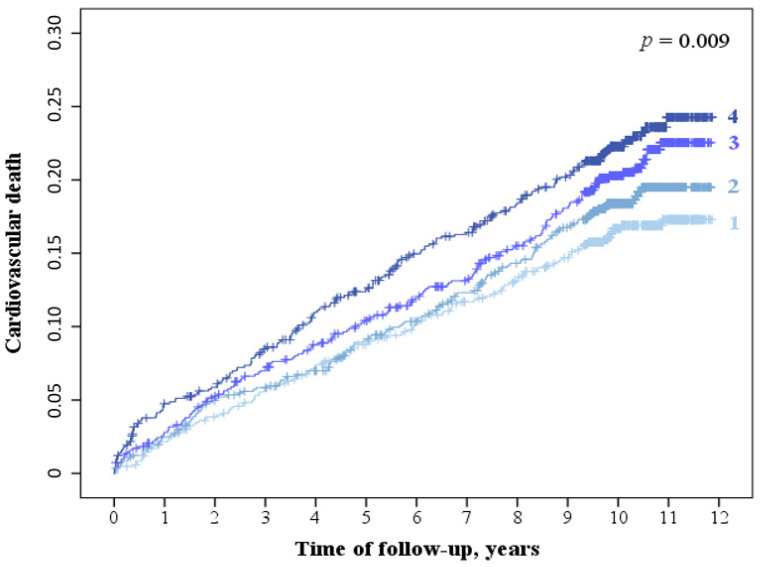

3.3. LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc Ratio and Cardiovascular Mortality

A total of 621 cardiovascular deaths occurred during the follow-up. The quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas were positively related to cardiovascular mortality (Figure 2) adjusted for sex, age, statin treatment, and interaction between statin treatment and LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles (Table 2). The association of the LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles with cardiovascular mortality remained significant after multivariate adjustment (Table 2). There was significant interaction between LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles and statin use in predicting cardiovascular mortality (p = 0.030). Stratified analyses revealed that quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas ratios were strongly and positively associated with cardiovascular mortality in statin-naïve patients adjusted for sex and age and after multivariate adjustment (Table 2). In contrast, quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas ratios were not associated with cardiovascular mortality in patients receiving statin treatment (Table 2). Consistent results were obtained for LDLapoB/LDLCcalc (Table 3). In agreement with the LURIC study, high LDLapoB/LDLCcalc quartiles were associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in the replication cohort (Supplementary Table S7). The sample size and the number of events were low for subgroup analyses.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for cardiovascular death according to LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles in the entire LURIC cohort. Legend: 1-4: LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles; p calculated with log-rank test.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular mortality according to LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles in the LURIC cohort.

| Model 1 * | Model 2 † | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | CD (%) | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Entire cohort | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 836 | 133 (15.9) | 1.0 reference | - | 1.0 reference | - |

| 2nd quartile | 810 | 145 (17.9) | 1.09 (0.81–1.47) | 0.575 | 0.98 (0.72–1.34) | 0.914 |

| 3rd quartile | 821 | 164 (20.0) | 1.62 (1.20–2.18) | 0.002 | 1.32 (0.96–1.82) | 0.087 |

| 4th quartile | 824 | 179 (21.7) | 2.07 (1.53–2.79) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.19–2.40) | 0.003 |

| Statin-naïve | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 605 | 92 (15.2) | 1.0 reference | - | 1.0 reference | - |

| 2nd quartile | 473 | 79 (16.7) | 1.07 (0.80–1.5) | 0.631 | 0.99 (0.73–1.35) | 0.949 |

| 3rd quartile | 349 | 81 (23.2) | 1.6 (1.18–2.16) | 0.002 | 1.38 (0.98–1.93) | 0.064 |

| 4th quartile | 321 | 84 (26.2) | 2.0 (1.51–2.75) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.25–2.70) | 0.002 |

| Statins | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 231 | 41 (17.7) | 1.0 reference | - | 1.0 reference | - |

| 2nd quartile | 337 | 66 (19.6) | 1.09 (0.74–1.62) | 0.656 | 1.01 (0.68–1.50) | 0.969 |

| 3rd quartile | 472 | 83 (17.6) | 1.05 (0.72–1.53) | 0.808 | 0.90 (0.60–1.33) | 0.581 |

| 4th quartile | 503 | 95 (18.9) | 1.25 (0.86–1.81) | 0.247 | 0.97 (0.63–1.49) | 0.884 |

Legend: N, number; CD, cardiovascular death; HR, hazard ratio (calculated with Cox regression); CI, confidence interval. * Adjusted for sex, age, statin use, and interaction between statin use and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc quartiles. † Model 1 with additional adjustment for body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking, and use of non-statin lipid-lowering drugs.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular mortality according to LDLapoB/LDLCcalc quartiles in the LURIC cohort.

| Model 1 * | Model 2 † | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | CD (%) | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Entire cohort | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 792 | 118 (14.9) | 1.0 reference | - | 1.0 reference | - |

| 2nd quartile | 793 | 148 (18.7) | 1.48 (1.09–2.00) | 0.012 | 1.41 (1.03–1.92) | 0.032 |

| 3rd quartile | 795 | 167 (21.0) | 1.71 (1.25–2.34) | 0.001 | 1.47 (1.04–2.06) | 0.028 |

| 4th quartile | 793 | 162 (20.4) | 1.83 (1.33–2.52) | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.12–2.44) | 0.011 |

| Statin-naïve | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 570 | 80 (14.0) | 1.0 reference | - | 1.0 reference | - |

| 2nd quartile | 462 | 89 (19.3) | 1.46 (1.08–1.98) | 0.014 | 1.48 (1.08–2.04) | 0.015 |

| 3rd quartile | 348 | 78 (22.4) | 1.69 (1.24–2.32) | 0.001 | 1.61 (1.12–2.31) | 0.011 |

| 4th quartile | 311 | 72 (23.2) | 1.81 (1.31–2.49) | <0.001 | 1.99 (1.29–3.07) | 0.002 |

| Statins | ||||||

| 1st quartile | 222 | 38 (17.1) | 1.0 reference | - | 1.0 reference | - |

| 2nd quartile | 331 | 59 (17.8) | 1.15 (0.77–1.74) | 0.493 | 1.08 (0.72–1.65) | 0.703 |

| 3rd quartile | 447 | 89 (19.9) | 1.34 (0.91–1.97) | 0.133 | 1.14 (0.76–1.71) | 0.531 |

| 4th quartile | 482 | 90 (18.7) | 1.37 (0.93–2.00) | 0.110 | 1.02 (0.64–1.63) | 0.927 |

Legend: N, number; CD, cardiovascular death; HR, hazard ratio (calculated with Cox regression); CI, confidence interval. * Adjusted for sex, age, statin use, and interaction between statin use and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc quartiles. † Model 1 with additional adjustment for body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, smoking, and use of non-statin lipid-lowering drugs.

3.4. LDLapoB/LDLCmeas, LDLapoB/LDLCcalc and LDL Subclass Particle Concentrations in the LDL Subfraction Cohort

The mean (standard deviation) LDLC and LDLapoB concentrations were 110 (36) and 86 (35) mg/dL, respectively. Higher quartiles of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas were associated with increased apoB concentration in the dense LDL fraction (LDL5 and LDL6) but were not associated with apoB concentration in the larger LDL fractions (Table 4). Consistent results were obtained for ratios of LDLapoB/LDLCcalc in the subgroup with triglyceride levels <400 mg/dL (Table 5).

Table 4.

LDLapoB in LDL subclasses according to LDLapoB/LDLCmeas quartiles.

| 1st Quartile | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 70 | 69 | 73 | 70 | - |

| LDL1apoB, mg/dL | 11.1 (5.9) | 10.3 (6.0) | 9.4 (5.2) | 10.6 (9.7) | 0.544 |

| LDL2apoB, mg/dL | 8.9 (4.7) | 7.6 (4.1) | 7.0 (3.9) | 7.2 (4.8) | 0.053 |

| LDL3apoB, mg/dL | 12.0 (5.9) | 11.0 (5.6) | 10.0 (5.1) | 9.9 (5.6) | 0.095 |

| LDL4apoB, mg/dL | 14.2 (6.7) | 16.0 (7.0) | 14.9 (6.6) | 9.9 (5.6) | 0.549 |

| LDL5apoB, mg/dL | 12.6 (6.8) | 17.3 (8.2) | 17.7 (9.4) | 19.6 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| LDL6apoB, mg/dL | 11.2 (5.0) | 15.9 (8.4) | 17.8 (8.8) | 22.1 (14.0) | <0.001 |

Legend: Values are means (standard deviations); lipoproteins were isolated by ultracentrifugation. The subfractions of LDLs were separated into six density classes by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation: LDL1, <1.031 kg/L; LDL2, 1.031–1.034 kg/L; LDL3, 1.034–1.037 kg/L; LDL4, 1.037–1.040 kg/L; LDL5, 1.040–1.044 kg/L; LDL6, >1.044 kg/L. LDL5 and LDL6 were considered small, dense LDLs. * For trends calculated with Analysis of Variance.

Table 5.

LDLapoB in LDL subclasses according to LDLapoB/LDLCcalc quartiles.

| 1st Quartile | 2nd Quartile | 3rd Quartile | 4th Quartile | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 66 | 67 | 67 | 67 | - |

| LDL1apoB, mg/dL | 10.3 (6.9) | 11.1 (6.2) | 9.8 (5.2) | 9.4 (5.7) | 0.389 |

| LDL2apoB, mg/dL | 7.9 (4.7) | 8.6 (4.3) | 7.3 (3.9) | 6.0 (4.2) | 0.122 |

| LDL3apoB, mg/dL | 10.3 (5.4) | 12.5 (5.9) | 10.5 (5.3) | 10.1 (5.4) | 0.043 |

| LDL4apoB, mg/dL | 12.6 (6.5) | 16.4 (6.7) | 16.1 (7.5) | 15.2 (7.1) | 0.007 |

| LDL5apoB, mg/dL | 12.3 (9.6) | 17.2 (8.5) | 18.4 (9.1) | 18.9 (9.1) | <0.001 |

| LDL6apoB, mg/dL | 11.2 (7.4) | 15.5 (9.0) | 18.4 (9.0) | 20.2 (11.3) | <0.001 |

Legend: Values are means (standard deviations). Lipoproteins were isolated by ultracentrifugation. The subfractions of LDLs were separated according into six density classes by equilibrium density gradient centrifugation: LDL1, <1.031 kg/L; LDL2, 1.031–1.034 kg/L; LDL3, 1.034–1.037 kg/L; LDL4, 1.037–1.040 kg/L; LDL5, 1.040–1.044 kg/L; LDL6, >1.044 kg/L; LDL5 and LDL6 were considered, dense LDLs. * For trends calculated with Analysis of Variance.

4. Discussion

The main finding in the present study was that elevated values for the ratios of both LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc were associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in LURIC participants and an independent replication cohort. In addition, higher values for LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc were associated with elevated levels of small, dense LDLs and lower mean LDL particle diameters. Therefore, this study has immediate practical implications, as it indicates that LDLapoB/LDLCcalc ratios based on the equations proposed by Baca and Warnick [10] and Friedewald et al. [20] may be used to estimate the atherogenic risk associated with small, dense LDLs. Importantly, the ESC/EAS 2019 guidelines for the treatment of dyslipidaemias strongly recommend the use of total apoB as an integral index for the entirety of atherogenic, apoB-containing lipoprotein particles [4]. Hence, information on concentrations of small, dense LDLs can be obtained using the simple LDLapoB/LDLCcalc equation at no additional laboratory cost. The required calculations can be readily integrated into any laboratory information system and do not require the use of a sophisticated methodology, such as ultracentrifugation, gradient gel electrophoresis, or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

In agreement with the LURIC cohort, several epidemiological studies, such as the Stanford Five-City Project [23] and the Quebec Cardiovascular Study [24], have confirmed positive correlations between levels of small, dense LDL particles and cardiovascular risk. Interestingly, we also observed particularly strong associations between elevated values of LDLapoB/LDLC and increased prevalence of peripheral artery disease. This finding is in agreement with recent findings of the Women’s Health Study [25]. We previously found in the LURIC cohort that not only patients with a mean small LDL particle diameter displayed increased cardiovascular risk; those patients exhibiting predominantly high LDL particle diameters also displayed increased risk [21]. In contrast, there was a continuous increase in cardiovascular risk conferred by increasing values of the LDLapoB/LDLC ratio. Patients with large mean LDL diameter simultaneously display elevated LDL triglyceride concentrations, whereas there was a continuous positive relationship between LDLapoB/LDLC and LDL triglycerides observed. Of relevance, high LDL triglyceride concentrations may potentially reflect the atherogenic effects of low hepatic lipase activity [13].

Small, dense LDL particles are considered highly atherogenic on a per particle basis as a result of several intrinsic features [1]. Firstly, dense LDLs are more likely to penetrate into the sub-intimal space and possess higher affinity for binding to arterial wall proteoglycans, thereby implicating enhanced retention in the sub-intimal space [1]. Small, dense LDLs equally exhibit a prolonged half-life in the circulation due to lower LDL receptor affinity and thus reduced hepatic uptake [26]. Taken together, these features render small, dense LDLs more susceptible to deposition in the arterial wall [27]. Accordingly, this consideration is consistent with the absence of significant associations between LDLapoB/LDLC ratio and cardiovascular mortality for patients under statin treatment. Potentially, increased catabolism of small, dense LDLs [28], induced by higher expression of the hepatic LDL receptor in response to statin medication [29], may have blunted the association of the LDLapoB/LDLC with cardiovascular mortality in these patients. Alternatively, the lack of an association between LDLapoB/LDLC ratio and cardiovascular mortality in statin users may be due to general confounding by lipid-lowering treatment. This has also been observed in other highly recognized epidemiological studies [30].

Small, dense LDLs are also more susceptible to modification by oxidation and glycation of their phospholipid and cholesteryl ester components [1]. Finally, cardiovascular risk associated with small, dense LDLs may be due to an unfavorable lipid composition compared with LDLs of larger size [31].

Another supportive observation was that subjects with high LDLapoB/LDLch ratios showed elevated C-reactive protein levels. Of interest, small, dense LDLs are preferentially enriched with apolipoprotein C-III, which may increase cardiovascular risk [32], not only by inhibition of lipoprotein lipase but also via alternative inflammasome activation [33]. Hence, the well-documented association between small, dense LDLs and inflammation [34] may also be accounted for by the pro-inflammatory effects of apolipoprotein C-III.

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first prospective study relating ratios of LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc to cardiovascular mortality. The results of the present analyses also extend recent findings from the replication cohort that the LDLC/apoB ratio was inversely related to major cardiovascular events [35]. Moreover, the study includes a comparison of the LDLapoB/LDLCmeas and LDLapoB/LDLCcalc ratios with direct measurements of LDL particle concentrations. We also performed a precise clinical and biochemical characterization of the study participants. In addition, we have reported on a long-term follow-up with a large number of endpoints yielding high statistical power. Finally, the results were confirmed in an independent replication cohort.

It may be a limitation of the present study that laboratory measurements were performed once at baseline only. Consequently, we were not able to account for possible changes in LDLapoB/LDLC ratios during the follow-up. Moreover, data on non-fatal cardiovascular endpoints were not collected in the LURIC study.

In conclusion, elevated levels of LDL particles relative to their cholesterol content were associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. The LDLapoB/LDLCcalc ratio may hold the potential to quantify the atherogenic risk associated with small, dense LDL particles using a simple methodology. Further studies are required, however, to support the use of this ratio in patient cohorts differing in ethnicity, gender, and lipid-lowering pre-treatment.

Abbreviations

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoprotein |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| apoB | Apolipoprotein B |

| LDLC | LDL cholesterol |

| LDLapoB | LDL apolipoprotein B |

| LURIC | Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health |

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines10061302/s1.

Author Contributions

G.S. designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. H.S. performed the laboratory analysis and reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.H.S. performed the statistical analysis and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.R. (Markus Reinthalerand) reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.R. (Martin Rief) performed the statistical analysis and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.E.K. reviewed and edited the manuscript. B.L. performed the statistical analysis and reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.C. critically appraised, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. J.R.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.D. designed the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. W.M. designed the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The LURIC Study was approved by the Landesärztekammer Rheinland-Pfalz (837.255.97(1394)). The confirmation study was approved by the ethics commission Vorarlberg (UN-2320).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave written, informed consent. All studies were performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

M.E.K. and W.M. are employees of Synlab, a company that offers testing for LDLC and LDLapoB.

Disclosures

G. Silbernagel reports grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Sanofi; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Amgen; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Bayer; personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo; and grants from Numares, outside the submitted work. H. Scharnagl reports personal fees from Sanofi, grants and personal fees from Amgen, grants from Unilever, grants from Numares, personal fees from Akcea, non-financial support from Abbott, and non-financial support from Denka Seiken, outside the submitted work. C. H. Saely has nothing to disclose. M. Reinthaler has nothing to disclose. M. Rief has nothing to disclose. Kleber is an employee of Synlab, outside the submitted work. B. Larcher has nothing to disclose. M. John Chapman reports grants and honoraria from Amgen, Kowa, and Pfizer, and personal fees for speakers’ bureau and consultancy activities from Amarin, Alexion, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, MSD, Sanofi, and Servier, outside the submitted work. J. R. Schaefer reports personal fees from Synlab Academy, grants from Dr. Reinfried Pohl Foundation, other support from B. Braun Melsungen, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Berlin Chemie, and personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. H. Drexel has nothing to disclose. W. März is an employee of Synlab and reports grants and personal fees from Siemens Healthineers, grants and personal fees from Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Amgen, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Danone Research, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Hoffmann LaRoche, personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Synageva, grants and personal fees from BASF, grants from Abbott Diagnostics, and grants and personal fees from Numares, outside the submitted work.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the 7th Framework Program (integrated projects AtheroRemo, grant agreement number: 201668; and RiskyCAD, project number: 305739) of the European Union, by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (project e:AtheroSysMed (Systems medicine of coronary heart disease and stroke), grant number: 01ZX1313A-K). The work was also supported as part of the Competence Cluster of Nutrition and Cardiovascular Health (nutriCARD), which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant number: 01EA1411A) and the Vorarlberger Landesregierung (Bregenz, Austria).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Borén J., Chapman M.J., Krauss R.M., Packard C.J., Bentzon J.F., Binder C.J., Daemen M.J., Demer L.L., Hegele R.A., Nicholls S.J., et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:2313–2330. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Angelantonio E., Sarwar N., Perry P., Kaptoge S., Ray K.K., Thompson A., Wood A.M., Lewington S., Sattar N., Packard C.J., et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302:1993–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman M.G., Ference B.A., Im K., Wiviott S.D., Giugliano R.P., Grundy S.M., Braunwald E., Sabatine M.S. Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1289–1297. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mach F., Baigent C., Catapano A.L., Koskinas K.C., Casula M., Badimon L., Chapman M.J., De Backer G.G., Delgado V., Ference B.A., et al. ESC Scientific Document Group.2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy S.M., Stone N.J., Bailey A.L., Beam C., Birtcher K.K., Blumenthal R.S., Braun L.T., de Ferranti S., Faiella-Tommasino J., Forman D.E., et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–e1143. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meeusen J.W. Is Small Dense LDL a Highly Atherogenic Lipid or a Biomarker of Pro-Atherogenic Phenotype? Clin. Chem. 2021;67:927–928. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvab075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampson M., Wolska A., Warnick R., Lucero D., Remaley A.T. A New Equation Based on the Standard Lipid Panel for Calculating Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol and Its Use as a Risk-Enhancer Test. Clin. Chem. 2021;67:987–997. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvab048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoogeveen R.C., Gaubatz J.W., Sun W., Dodge R.C., Crosby J.R., Jiang J., Couper D., Virani S.S., Kathiresan S., Boerwinkle E., et al. Small dense low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol concentrations predict risk for coronary heart disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014;34:1069–1077. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langlois M.R., Chapman M.J., Cobbaert C., Mora S., Remaley A.T., Ros E., Watts G.F., Borén J., Baum H., Bruckert E., et al. European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (EFLM) Joint Consensus Initiative. Quantifying Atherogenic Lipoproteins: Current and Future Challenges in the Era of Personalized Medicine and Very Low Concentrations of LDL Cholesterol. A Consensus Statement from EAS and EFLM. Clin. Chem. 2018;64:1006–1033. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.287037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baca A.M., Warnick G.R. Estimation of LDL-associated apolipoprotein B from measurements of triglycerides and total apolipoprotein B. Clin. Chem. 2008;54:907–910. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.100941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkelmann B.R., März W., Boehm B.O., Zotz R., Hager J., Hellstern P., Senges J., LURIC Study Group (LUdwigshafen RIsk and Cardiovascular Health) Rationale and design of the LURIC study—A resource for functional genomics, pharmacogenomics and long-term prognosis of cardiovascular disease. Pharmacogenomics. 2001;2((Suppl. 1)):S1–S73. doi: 10.1517/14622416.2.1.S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silbernagel G., Schöttker B., Appelbaum S., Scharnagl H., Kleber M.E., Grammer T.B., Ritsch A., Mons U., Holleczek B., Goliasch G., et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, coronary artery disease, and cardiovascular mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:3563–3571. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silbernagel G., Scharnagl H., Kleber M.E., Delgado G., Stojakovic T., Laaksonen R., Erdmann J., Rankinen T., Bouchard C., Landmesser U., et al. LDL triglycerides, hepatic lipase activity, and coronary artery disease: An epidemiologic and Mendelian randomization study. Atherosclerosis. 2019;282:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41((Suppl. 1)):S13–S27. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drexel H., Aczel S., Marte T., Benzer W., Langer P., Moll W., Saely C.H. Is atherosclerosis in diabetes and impaired fasting glucose driven by elevated LDL cholesterol or by decreased HDL cholesterol? Diabetes Care. 2005;28:101–107. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mancia G., Fagard R., Narkiewicz K., Redón J., Zanchetti A., Böhm M., Christiaens T., Cifkova R., De Backer G., Dominiczak A., et al. Task Force Members. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) J. Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scharnagl H., Winkler K., Mantz S., Baumstark M.W., Wieland H., März W. Inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase with cerivastatin lowers dense low density lipoproteins in patients with elevated fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2004;112:269–277. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stojakovic T., de Campo A., Scharnagl H., Sourij H., Schmölzer I., Wascher T.C., März W. Differential effects of fluvastatin alone or in combination with ezetimibe on lipoprotein subfractions in patients at high risk of coronary events. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2010;40:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karoff J., Kittel J., Wagner A.M., Karoff M. Randomisierte, kontrollierte Interventionsstudie zum Vergleich von kohlenhydratreduzierter mit leitliniengemäßer Ernährung in der Therapie des Typ-2-Diabetes. DRV-Schr. 2015;107:271–273. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedewald W.T., Levy R.I., Fredrickson D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972;18:499–502. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/18.6.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grammer T.B., Kleber M.E., März W., Silbernagel G., Siekmeier R., Wieland H., Pilz S., Tomaschitz A., Koenig W., Scharnagl H. Low-density lipoprotein particle diameter and mortality: The Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study. Eur. Heart J. 2015;36:31–38. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baumstark M.W., Kreutz W., Berg A., Frey I., Keul J. Structure of human low-density lipoprotein subfractions, determined by X-ray small-angle scattering. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1037:48–57. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(90)90100-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner C.D., Fortmann S.P., Krauss R.M. Association of small low-density lipoprotein particles with the incidence of coronary artery disease in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276:875–881. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540110029028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamarche B., Tchernof A., Moorjani S., Cantin B., Dagenais G.R., Lupien P.J., Despres J.P. Small, dense low density lipoprotein particles as a predictor of the risk of ischemic heart disease in men. Prospective results from the Quebec Cardiovascular Study. Circulation. 1997;95:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.95.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aday A.W., Lawler P.R., Cook N.R., Ridker P.M., Mora S., Pradhan A.D. Lipoprotein Particle Profiles, Standard Lipids, and Peripheral Artery Disease Incidence. Circulation. 2018;138:2330–2341. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nigon F., Lesnik P., Rouis M., Chapman M.J. Discrete subspecies of human low density lipoproteins are heterogeneous in their interaction with the cellular LDL receptor. J. Lipid Res. 1991;32:1741–1753. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)41629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ference B.A., Ginsberg H.N., Graham I., Ray K.K., Packard C.J., Bruckert E., Hegele R.A., Krauss R.M., Raal F.J., Schunkert H., et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:2459–2472. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.März W., Scharnagl H., Abletshauser C., Hoffmann M.M., Berg A., Keul J., Wieland H., Baumstark M.W. Fluvastatin lowers atherogenic dense low-density lipoproteins in postmenopausal women with the atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype. Circulation. 2001;103:1942–1948. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.15.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein J.L., Brown M.S. A century of cholesterol and coronaries: From plaques to genes to statins. Cell. 2015;161:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johannesen C.D.L., Langsted A., Mortensen M.B., Nordestgaard B.G. Association between low density lipoprotein and all cause and cause specific mortality in Denmark: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371:m4266. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapman M.J., Orsoni A., Tan R., Mellett N.A., Nguyen A., Robillard P., Giral P., Thérond P., Meikle P.J. LDL subclass lipidomics in atherogenic dyslipidemia: Effect of statin therapy on bioactive lipids and dense LDL. J. Lipid Res. 2020;61:911–932. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P119000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silbernagel G., Scharnagl H., Kleber M.E., Hoffmann M.M., Delgado G., Stojakovic T., Gary T., Zeng L., Ritsch A., Zewinger S., et al. J-shaped association between circulating apoC-III and cardiovascular mortality. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021. online ahead of print . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Zewinger S., Reiser J., Jankowski V., Alansary D., Hahm E., Triem S., Klug M., Schunk S.J., Schmit D., Kramann R., et al. Apolipoprotein C3 induces inflammation and organ damage by alternative inflammasome activation. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:20–41. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norata G.D., Raselli S., Grigore L., Garlaschelli K., Vianello D., Bertocco S., Zambon A., Catapano A.L. Small dense LDL and VLDL predict common carotid artery IMT and elicit an inflammatory response in peripheral blood mononuclear and endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2009;206:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drexel H., Larcher B., Mader A., Vonbank A., Heinzle C.F., Moser B., Zanolin-Purin D., Saely C.H. The LDL-C/ApoB ratio predicts major cardiovascular events in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2021;329:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data may be made available upon request.