Abstract

Background:

PrEP use is low among Black same gender–loving men (BSGLM) in Mecklenburg County, NC, an Ending the HIV Epidemic priority jurisdiction. We created PrEP-MECK—an investigator partnership among a community-based organization representative, a PrEP provider, and researchers—and conducted iterative preparation research to identify determinants of PrEP uptake and implementation strategies to address them.

Methods:

We first established the PrEP-MECK Coalition of community stakeholders. Next, informed by PrEP-MECK Coalition input and PRECEDE-PROCEED’s educational/ecological assessment phase, we conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with BSGLM not using PrEP and in-depth interviews (IDIs) with BSGLM who were currently or had previously taken PrEP to describe determinants and suggest implementation strategies. Based on interim findings, we partnered with clinics participating in the Mecklenburg County PrEP Initiative (MCPI), which offers free PrEP services to uninsured individuals. We also conducted CFIR-informed organizational assessments with CBOs and clinics to assess readiness to pilot the implementation strategies.

Results:

We conducted 4 FGDs, 17 IDIs, and 6 assessments. BSGLM were aware of PrEP yet perceived that costs made it unattainable. Awareness of how to access PrEP and the MCPI was lacking, and clinic scheduling barriers and provider mistrust limited access. We identified client-level implementation strategies, primarily focusing on engaging the consumer, to increase comfort with and awareness of how to access PrEP, and clinic-level implementation strategies focusing on changing clinic infrastructure, to make PrEP access easier.

Conclusion:

We plan to evaluate implementation of these strategies once fully developed to determine their acceptability and other outcomes in future research.

Keywords: HIV, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, Implementation Strategies, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. U.S. South

Introduction

Due to systemic processes that disadvantage Black Americans, Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) are the demographic group at greatest risk of HIV in the US. During their lifetimes, 1 out of every 2 BMSM will receive an HIV diagnosis.1 In the US South—the epicenter of the HIV epidemic in the US2—HIV diagnosis rates show the disproportionate impact of HIV among BMSM: nearly twice as many BMSM are diagnosed with HIV compared to White and Hispanic/Latinx BMSM.2

In both 2019 and 2020, we received a 1-year Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) supplemental award to support the Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative.3 The intervention population for these planning grants is Black same gender–loving men (BSGLM) in the US South, specifically in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, an EHE priority jurisdiction.4 (We use “BSGLM” instead of “BMSM” due to community preference.) Information about Mecklenburg County and local HIV-related data is found in Section 1 of the Supplemental Digital Content.

Our long-term goal is to increase the uptake of PrEP, an effective HIV prevention intervention,5,6 among BSGLM. During these planning grants, our immediate goals were to identify, develop, and plan for a pilot evaluation of implementation strategies that will (1) enhance a community-based organization’s (CBO) existing PrEP promotion efforts, and (2) extend PrEP delivery by local PrEP providers. We named our project “PrEP-MECK” because it focuses on PrEP uptake in MECKlenburg County.

In this paper, we describe the process we followed for identifying determinants and selecting implementation strategies that we will evaluate in subsequent implementation research.

Methods

Multiple implementation science frameworks and models guided our project. We first established a core multi-disciplinary team of investigators to collectively inform and implement the planning activities, following the “build the coalition” strategy from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation of implementation strategies.7 The investigator partnership consisted of a representative of a culturally diverse CBO that includes BSGLM with strong community connections; a well-established, local PrEP provider who provides routine HIV-related care to the LGBTQ community; and Duke CFAR researchers with expertise in PrEP and in HIV-related studies in Mecklenburg County. Both the CBO and provider investigators serve in executive leadership positions at their respective institutions. We wanted planning decisions to be driven by local needs based on data from the intervention population coupled with expert knowledge and experiences with programs and services that work best locally.

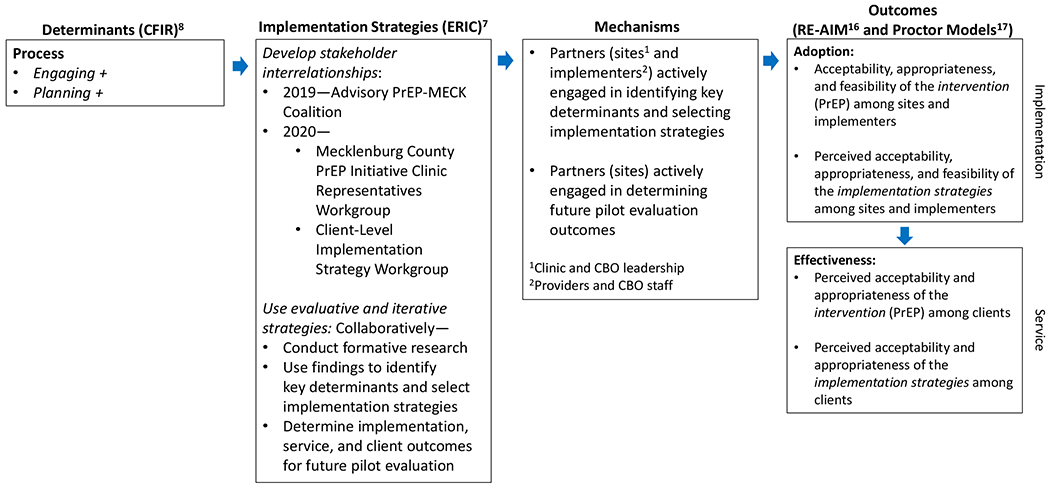

As displayed in our implementation preparation logic model (Figure 1), we, the investigator partnership, used two additional ERIC strategies—“develop stakeholder interrelationships” (specifically “use advisory boards and workgroups”) and “use evaluative and iterative strategies” (specifically “assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators”)7—to leverage two process determinants of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)8—“engaging” (involving internal implementation leaders) and “planning” (engaging leaders in the full development process). We also used constructs from the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model’s9 educational and ecological assessment phase (i.e., predisposing factors, reinforcing factors, and enabling factors) to guide our formative research with BSGLM, and CFIR to guide our assessments with clinics and CBOs. We describe in detail below.

Figure 1: The PrEP-MECK Logic Model for Implementation Preparation.

Abbreviations:

CFIR: Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

ERIC: Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change.

RE-AIM: Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance

Develop Stakeholder Interrelationships

We created 3 stakeholder advisory and working groups which contributed significantly to (1) informing the formative research described below, and (2) using the formative research findings coupled with their own expertise to identify and select community-driven implementation strategies at the clinic and client levels to increase PrEP uptake among BSGLM. We briefly describe roles and activities here; details are found in Section 2 of the Supplemental Digital Content.

Advisory PrEP-MECK Coalition

As part of the 2019 EHE award, the newly created multi-disciplinary investigator team established the PrEP-MECK Coalition to advise the project. We mobilized community representatives from local CBOs, the Mecklenburg County Public Health Department, local PrEP clinics, and BSGLM not affiliated with any organization. The PrEP-MECK coalition met 4 times to inform the formative research and discuss key determinants and implementation strategies to address them.

Mecklenburg County PrEP Initiative Clinic Representatives Workgroup

Based on interim focus group discussion (FGD) findings that suggested BSGLM perceive PrEP as unaffordable and are unaware of clinics that provide PrEP, we expanded our partnership in the EHE 2020 award to include representatives from clinics participating in the Mecklenburg County PrEP Initiative (MCPI). As part of the MCPI, residents of Mecklenburg County who do not have health insurance can obtain free PrEP services from participating community clinics. We reached out to all 7 of the MCPI clinics, and 4 clinics with the highest volume of PrEP clients were willing to collaborate with us. All clinics currently deliver PrEP to BSGLM, and the director of one of the clinics is an investigator on our EHE supplemental awards. As a result of this new partnership, we modified our initial immediate goals to include implementation strategies that focus on increasing BSGLM’s awareness of the MCPI and linking BSGLM to the 4 MCPI partner clinics. The MCPI clinic representatives participated in 6 workgroup meetings and primarily focused on the identification of clinic-based implementation strategies and outcomes.

Client-Level Implementation Strategy Workgroup

After the formative research was completed, we created a workgroup to identify and plan the client-level implementation strategies (“engage the consumer”) based on the formative research findings. The group consisted of the CBO investigator and staff who regularly interacted with BSGLM through service delivery, a BSGLM representative, research staff with experience in developing client-level interventions, and CFAR investigators. Through a series of larger and smaller meetings, the workgroup created mock content of the client-level implementation strategies for pre-testing.

Use Evaluative and Iterative Strategies

We conducted formative research using FGDs and in-depth interviews (IDIs) with BSGLM and assessments with CBOs and clinics. The primary purpose of the formative research was to identify factors (e.g., barriers and facilitators) that influence PrEP uptake among BSGLM, gather suggested methods for enhancing initial engagement in PrEP care among BSGLM, and determine the readiness of the CBOs and clinics to adopt the implementation strategies.

Focus Group Discussions and In-Depth Interviews

We conducted FGDs with BSGLM not using PrEP and focused on identifying participants’ perspectives on how BSGLM in their community view (1) predisposing factors (e.g., PrEP awareness, attitudes, and beliefs, including constructs of the Health Belief Model10 and Stages of Change [Transtheoretical] Model11), (2) reinforcing factors that support or encourage PrEP use (such as perceptions of social norms, social support, stigma and discrimination, medical mistrust, and provider interactions), and (3) enabling factors that must be in place to use PrEP (e.g., availability of resources and the availability and accessibility of services). We also conducted IDIs with BSGLM who were currently or had previously taken PrEP. We asked about predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors that contributed to current PrEP users’ motivation for taking PrEP, support in taking PrEP, and strategies to manage barriers, as well as PrEP discontinuers’ reasons for stopping PrEP and any plans for re-initiation. We also explored the relevance of common barriers to PrEP uptake during the FGDs and suggestions for future implementation strategies to increase PrEP uptake among BSGLM in both the FGDs and IDIs. The CBO and clinic partners recruited participants via social media and direct outreach to current clients.

Using applied thematic analysis,12 we coded verbatim transcripts with deductive and inductive codes, and organized codes into emergent thematic groups that described the salient PRECEDE-PROCEED model factors that influence PrEP uptake. Detailed information about the FGD and IDI recruitment, methods, and analysis is described in Section 3 of the Supplemental Digital Content.

Organizational and Clinic Assessments

We assessed clinics’ and CBOs’ clinic/organization structure, implementation climate, and readiness to adopt new strategies to expand clinic access and community outreach for PrEP promotion to BSGLM, respectively. Additional details are found in Section 4 of the Supplemental Digital Content.

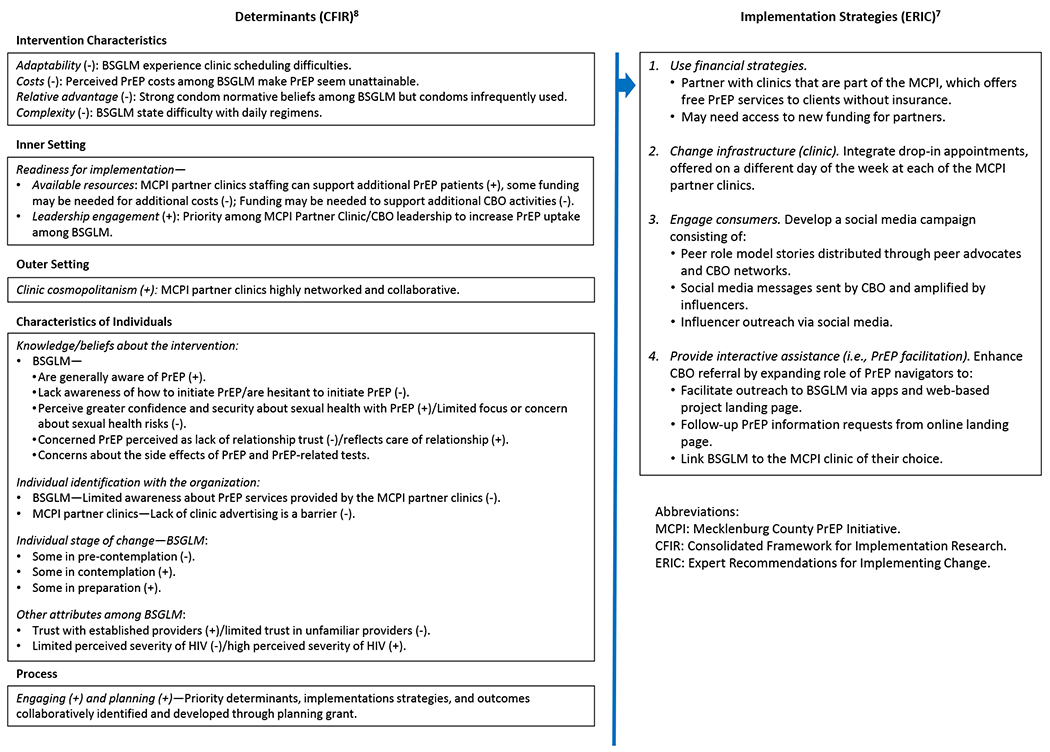

Applying the formative research findings

After we identified the key findings within the constructs of the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model9 for the FGD and IDI findings, we mapped them, together with the findings from the organizational assessments, to the implementation determinant constructs of the CFIR Framework,8 selected implementation strategies to address the determinants based on the ERIC compilation of implementation strategies,7 and placed the implementation determinants and strategies in a pilot implementation logic model (Figure 2).13

Figure 2: The PrEP-MECK Logic Model (Determinants and Implementation Strategies) for the Future Pilot.

Abbreviations:

MCPI: Mecklenburg County PrEP Initiative.

CFIR: Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

ERIC: Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change.

Ethics Review

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Duke University Health System reviewed and approved PrEP-MECK’s research components. The IRB waived informed consent for FGD participants, although we provided participants with an informational sheet; IDI participants provided oral consent; and the IRB waived the need for consent for the assessments.

Results

From March to September 2020, we conducted 4 FGDs with BSGLM, including 2 FGDs with BSGLM ages 25 to 30 years and 2 FGDs with BSGLM ages 31 to 39 years. Three to 4 men participated in each FGD, for a total of 13 participants. All but 1 BSGLM had never taken PrEP. We conducted 17 IDIs with BSGLM, 12 with current PrEP users and 5 with former PrEP users. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the participants. In brief, all participants had at least a high school education or the equivalent, most were working full-time (12 IDI participants, 11 FGD participants), almost all IDI participants (n=14) and over half of the FGD participants (n=8) had private health insurance, and a range of monthly incomes were reported.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristic | Focus Group Participants, No. (%) | Interview Participants, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 25 to 30 Years (n = 6) | Age 31 to 39 Years (n = 7) | Total (n = 13) | PrEP Users (n = 12) | Former PrEP Users (n = 5) | Total (n = 17) | |

| Number of focus group discussions | 2 | 2 | 4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 20-24 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 1 (20) | 3 (18) |

| 25-29 | 5 (83) | 0 (0) | 5 (38) | 5 (42) | 0 (0) | 5 (29) |

| 30-34 | 1 (17) | 4 (57) | 5 (38) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | 4 (24) |

| 35-39 | 0 (0) | 3 (43) | 3 (23) | 3 (25) | 0 (0) | 3 (18) |

| 40-49 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 5 (83) | 7 (100) | 12 (92) | 11 (92) | 4 (80) | 15 (88) |

| Prefer not to respond | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Black or African American | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 13 (100) | 12 (100) | 5 (100) | 17 (100) |

| Highest level of education | ||||||

| High school or equivalent | 4 (67) | 1 (14) | 5 (38) | 1 (8) | 1 (20) | 2 (12) |

| Some college | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | 2 (15) | 3 (25) | 3 (60) | 6 (35) |

| Associate’s degree | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 (17) | 4 (57) | 5 (38) | 7 (58) | 1 (20) | 8 (47) |

| Employment | ||||||

| Part-timea | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 2 (40) | 3 (18) |

| Full-timeb | 5 (83) | 6 (86) | 11 (85) | 10 (83) | 2 (40) | 12 (71) |

| Full-time student | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Unemployed | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (6) |

| Income in the previous month | ||||||

| $0 to $500 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| $501 to $1000 | 1 (17) | 1 (14) | 2 (15) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| $1001 to $1500 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| $1501 to $2000 | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 2 (17) | 2 (40) | 4 (24) |

| $2001 to $2500 | 2 (33) | 1 (14) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (6) |

| $2501 to $3000 | 0 (0) | 3 (43) | 3 (23) | 1 (8) | 1 (20) | 2 (12) |

| $3001 to $4000 | 1 (17) | 2 (29) | 3 (23) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| $4001 or more | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Unsure | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Prefer not to respond | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 1 (20) | 2 (12) |

| Type of health insurance | ||||||

| Private insurance | 4 (67) | 4 (57) | 8 (62) | 12 (100) | 2 (40) | 14 (82) |

| No insurance | 1 (17) | 3 (43) | 4 (31) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 2 (12) |

| Medicaid | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (6) |

| Unsure | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sexual orientationc | ||||||

| Gay or same gender-loving | 3 (50) | 7 (100) | 10 (77) | 11 (92) | 5 (100) | 16 (94) |

| Queer | 3 (50) | 1 (14) | 4 (31) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Bisexual | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Asexual | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Demisexual | 1 (17) | 1 (14) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Otherd | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (6) |

| Sexual attractionc | ||||||

| Cisgender men | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 13 (100) | 11 (92) | 4 (80) | 15 (88) |

| Cisgender women | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Transgender women | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Transgender men | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | 2 (15) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| Attracted to anyone | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (6) |

| Othere | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unsure | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Single | 4 (67) | 4 (57) | 8 (62) | 8 (67) | 2 (40) | 10 (59) |

| Married | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not married but in a committed relationship(s) | 2 (33) | 2 (29) | 4 (31) | 3 (25) | 2 (40) | 5 (29) |

| It’s complicated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 1 (20) | 2 (12) |

| Anal sex with cisgender man within past 6 monthsf | ||||||

| 0 partners | 1 (17) | 1 (14) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1 partner | 1 (17) | 2 (29) | 3 (23) | 3 (25) | 1 (20) | 4 (24) |

| 2 or 3 partners | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (15) | 4 (33) | 2 (40) | 6 (35) |

| 4 or more partners | 2 (33) | 4 (57) | 6 (46) | 5 (42) | 2 (40) | 7 (41) |

| Sex with a gender-nonconforming person within past 6 months | ||||||

| 1 person | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (6) |

| Anal sex with transgender woman within past 6 months | ||||||

| 2 or 3 partners | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Vaginal or anal sex with cisgender woman within past 6 months | ||||||

| 0 partners | 6 (100) | 7 (100) | 13 (100) | 12 (100) | 4 (80)g | 16 (94) |

| Number of HIV tests in lifetime | ||||||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | NA | NA | NA |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (8) | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 to 9 | 4 (67) | 1 (14) | 5 (38) | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 or more | 2 (33) | 4 (57) | 6 (46) | NA | NA | NA |

| How often think about exposure to HIV | ||||||

| Rarely | 1 (17) | 1 (14) | 2 (15) | NA | NA | NA |

| Some of the time | 3 (50) | 2 (29) | 5 (38) | NA | NA | NA |

| Often | 2 (33) | 4 (57) | 6 (46) | NA | NA | NA |

| Have not previously taken PrEP | 6 (100) | 6 (86) | 12 (92) | NA | NA | NA |

Working less than 35 hours per week, could include labor pool and or day work (includes self-employed).

Working 35 hours or more per week (includes self-employed).

Participants selected all that applied.

Unspecified.

One participant reported “masculinity.”

Bottom, top, or verse.

Data missing for 1 participant.

We also conducted 6 assessments from January to February 2021. The 2 CBOs have 6 and 10 staff dedicated to HIV prevention and care service activities, and 14 and 6 staff, respectively, dedicated to implementing community-based programs. Of the 4 partner MCPI clinics, 3 clinics have 2 providers and 1 clinic has 7 providers. The estimated number of PrEP clients range from 40 to 600, and for 3 clinics, nearly all their clients are BSGLM (85% to 98%); 1 clinic reported that 45% of their PrEP clients are BSGLM (see Section 4, Supplemental Digital Content).

Key Focus Group Discussions and In-Depth Interview Findings

Illustrative participant quotes are found in Tables 2 and 3 and in Supplement Table 1 in Section 3 of the Supplemental Digital Content.

Table 2.

Participant Quotes for the CFIR Construct “Intervention Characteristics” by Sub-Construct and Topic

| Sub-construct | Topic | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptability | Scheduling clinic visits | Because if you’ve got work, you get days off, but sometimes you don’t know when…Like the day that you have off can’t fit in with the schedule that you need for the person [providing] PrEP…It might sometimes just be difficult to get off of work and trying to get [PrEP], too.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) |

| Oh my god, the days just are not long enough anymore. People are juggling so much. And, they put something off for the next day, and then that piles up with the things that were already on that day. There just is not enough time in the day anymore it seems like.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Costs | PrEP and PrEP-related care | [BSGLM need to know more about] the financial side of it. A lot of people think you have to pay so much more money for it just to be on it, and a lot of people think that’s just another cost that they pay for.—Participant in FGD #3 (ages 25 to 30 years) |

| [What makes it hard to see a PrEP provider is] having insurance or not. I think that’s probably one of the big things with the people that don’t have medical insurance. What do they got? I think that’s their question.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| [I]f you wanna keep talking about value your health, it’s more than just this [that BSGLM don’t want to tell providers that they’re gay]…why they don’t take good care of themselves. [There are] economic reasons why they don’t seek the treatment.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Excerpt from FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years): Participant #1: We are living paycheck to paycheck nowadays. And anything extra that’s coming out of pocket is gonna throw something else off that needs to be paid for. My money gone before I even get it. So, we’re throwing something else in there. And, now I have to make sure that I can pay for [PrEP]. Participant #2: You got an Amen on that…. Participant #1: If there are resources out there that could help so that they don’t have to go and pick up another job, I think that information needs to be out there just in case [BSGLM] need some kind of other assistance…and are researching it. | ||

| Relative advantage | Condom normative beliefs | I feel like [using condoms] is always expected. It should be, at least. But…in the Black gay community, they love the raw, authentic sex. They feel, they love the pleasure and the feel of it versus a condom. So, you would think people would always wanna protect themselves and the other person by using a condom, but it’s not always the first thought. And like I said, in the Black community, using condoms is not the top priority. —Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) |

| I feel like that’s kinda why I feel like condoms is just something that sounds good on paper to say, “Oh, I’m using a condom,” but that’s not how we feel. —Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) | ||

| Complexity | Daily commitment | Also, taking a pill every single day. I think that is something that people—me—dread. I think that’s one of the big reasons why I haven’t started PrEP yet, because I can’t commit to it, and they just make you take it every single day. I think that’s an issue. Yeah, I do think that it’s hard to add on routines to your current routines. I just think that would be a challenge with just taking a pill every single day.—Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) |

| People aren’t willing to take it because it could be an inconvenience. I’m going to now have to worry about taking this every day for the next three to six months. And, it could be like if you don’t take it, it won’t work.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) |

Abbreviations. CFIR: Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research; FGD: Focus group discussion.

Table 3.

Participant Quotes for the CFIR Construct “Characteristics of Individuals” by Sub-Construct and Topic

| Sub-construct | Topic | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge/beliefs about the intervention | ||

| Awareness | General | You gotta know about [PrEP]. It’s on BET channel all day. [Laughter].— Participant in FGD #3 (ages 25 to 30 years) |

| [BSGLM] have all heard about [PrEP] but aren’t actually using it.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Awareness plus other factors | Knowledge | [B]eing here in North Carolina, yeah, I’ve heard it more recently…But I haven’t really been educated on it.—Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) |

| Initiating care | [Y]ou got a TV, you know about [PrEP]. But do you actually take the steps of going to your doctor?—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| Access and finance | I do feel, because this is a topic of discussion I’ve had with my friends on several occasions, that the knowledge is there. But, the actual access and financial resources to [using PrEP] is not available.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| Well, I think what information isn’t getting out there is that [PrEP is] available to you through different programs where you don’t have to pay for it.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Initiation | How to | I feel like a lot of Black men in our community, and specifically here in Charlotte, don’t even have someone who they see regularly when it comes to medical care. And, if they don’t have access to that, they don’t know how to gain access. Some of them don’t even know where to start.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) |

| Hesitancy | Because first, you don’t wanna tell your doctor you’re gay. That’s the first thing, you don’t wanna say that. Because you’re be so embarrassed. Well, that Black pride thing.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| There’s an insecurity going to the doctor, talking about HIV/AIDS and PrEP. It’s an uncomfortable conversation.—Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) | ||

| When I go to my doctor to get tested, I don’t see too many people in there. Not people that look like me in there, I’ll put it like that.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Sexual health | General | [PrEP provides] confidence in sex life, maybe…it’s like an added insurance policy to your life. You’re adding value to what you’re doing every day.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) |

| Liberation | It’s sexually liberating [for BSGLM to take PrEP]…I would feel like I can have a partner that is positive and not be afraid, or not feel that I have to take other precautions about the type of sex with that person. So, I would be more inclined to date somebody that’s positive. —Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) | |

| Not a priority | I feel like Black men feel like they are invincible…It’s a pattern that [BSGLM] just go out and start wilding out and just think that no harm can come to me. So, we cover [i.e., use a condom], but not that much. —Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| That’s the question. It’s not gonna be, “[Do you have a] STD, STI?” You don’t have the discussion. [Instead, you have] straight-language, “Are you top? Bottom? Where you located? I’m on my way.” —Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Relationship | Positive | [Using PrEP] shows a lot of initiative. It shows that you actually care.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) |

| Negative | [I]it could be a negative thing if both parties were tested and neither of them are negative and one of them wants to be on PrEP, it could be a trust issue. —Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| PrEP side effects | General comments | I’ve heard a lot of guys say, [because of] all the side effects, they don’t take it.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) |

| Truvada lawsuit advertisements | I think [the Truvada lawsuit commercial] is a concern for a lot of people…the underlining tone is there is a lot of concern there, or a lot of unanswered questions. Especially being that there hasn’t been any type of rebuttal against that from the pharmaceutical companies. I think there is still underlining [worry] and scare there because there is no rebuttal… —Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) | |

| Pharmaceutical advertisements | I think [pharmaceutical TV advertisements for PrEP] are wonderful to have. But, I think what scares people…[is that people are] “Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.” Because if I get PrEP, it’s supposed to help me prevent HIV. But, at the same time, [it’s] giving me heart conditions, loss of bone density. It’s saying that it can cause liver and kidney problems. What the hell am I gonna do with that? .—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| Testing | General | Nobody likes to get tested. It’s anxiety…Your blood pressure goes up, some people get high, some people pass out, some people get attitudes, some people ready to fight. —Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) |

| Individual identification with the organization | ||

| Mecklenburg County PrEP Initiative | Awareness among Black same gender–loving men | People don’t know [of the MCPI program]…And, when people think that with maybe not having insurance or enough insurance, [they think] that these medications are expensive. —Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) |

| I think what information isn’t getting out there is that [PrEP is] available to you through different programs where you don’t have to pay for it.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Individual stage of change | ||

| Pre-contemplation | Because most people…are actually scared to go in and get tested for [HIV]. So, even going to get the preparation about PrEP, we still have to get tested for HIV, so those are the things that scare them.—Participant in FGD #3 (ages 25 to 30 years) | |

| [M]ost same gender–loving Black men just don’t feel comfortable enough to talk about [PrEP], or some of them. It’s different avenues here. Some of them don’t feel comfortable. Some of them are not openly honest with their provider. The provider may not even know they are same gender–loving Black gay men. And then some of them probably just don’t care enough. I know that sounds terrible. —Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Contemplation | I feel like most of the Black gay men are here: They got the information. They’re interested, but they still need another push, and then they’ll get there.—Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| It’s just [BSGLM] aren’t motivated by the right people…They’re not saying they’re opposed to it. They’re just not around the right people who actually are making sure they get treatment or making sure they are getting seen regularly…. you just need an extra person there to advocate for you. —Participant in FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years) | ||

| Preparation | I do think that PrEP is a big topic. I think the follow-through is what we need help with. [BSGLM men think] “I’ve heard about it. I’ve talked about it. I’ve had a couple conversations about it. Hell, I’ve even visited a table and seen something about it.” But the follow-through of actually going to talk to a healthcare provider is the issue or the problem.—Participant in FGD # 1 (ages 25 to 30 years) | |

| Other attributes | ||

| Provider trust | General | Excerpt from FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years): (Participant #1): I can only speak for myself on that one. I trust mine. I whole-heartedly trust mine. (Participant #2): I think that’s the reason people don’t go to the doctors, though, because people don’t trust them. (Participant #3): Maybe they feel like they won’t understand them as a Black person. |

| Sexuality | I think that’s why maybe in the gay community, we are scared to go and tell you, the straight doctor, the straight Black doctor looking at me, “Hey, this is what’s going on with me.” You can still see there’s still that fear of just letting your guard down and telling people…but we have a fear as a Black man to go in there and tell another Black man this is what it is. You go in there, and he’s got a picture of his wife and kids in there? You really don’t wanna say shit. Now he’s looking at you, like “Ain’t this a bitch”. So, we’re scared of who you’re facing across that desk when you go in there.—Participant in FGD #4 (ages 31 to 39 years) | |

| Confidentiality | [It’s] not so much [that Black men do not trust medical providers]. I don’t think they trust anybody…that’s why I said in the beginning about the letting people know it’s very private about what we’re talking about when it comes down to each other’s status…Confidential, I guess you could say…. —Participant in FGD #3 (ages 25 to 30 years) | |

| Rapport | Because you have to build up that rapport. You have to be able to trust that person with a lot of confidential information, being able to share your lifestyle and share things that go on in it. —Participant in FGD #1 (ages 25 to 30 years) | |

| Severity of HIV | Excerpt from FGD #2 (ages 31 to 39 years): (Participant #1): I feel like in today’s society, [BSGLM] are not afraid of it happening to them. We’re not seeing our peers and our people dying from it at a rapid rate. It’s more, “Oh, if I get it, well, then I’ll just take the medicine, and I’ll live another 30-40 years with no problem.” The scare is not there. So, I don’t think that they’re feeling that they can’t get it. They’re just not afraid of getting it. And, then a lot of people are trying to do away with the stigma if you do get it…So, it’s almost like if I get it, I’m not afraid. I’m not worried about what people are gonna think about me anymore. They’re just not afraid. (Participant #2): I do feel like on the opposite side of them feeling invincible. I do feel like there’s a big fear. So, you are fearful of finding out results. Because a lot of people after they’ve had unprotected sex, they don’t… get tested. They don’t. So, I think sometimes the fear is so great, it’s just like, “Well, I’ll just rather not know as opposed to know.” | |

Abbreviations. CFIR: Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research; FGD: Focus group discussion.

Predisposing Factors

Participants in all 4 focus groups voiced that BSGLM in Charlotte have heard about PrEP, although some believed that more education about PrEP is needed. Participants elaborated that lack of PrEP awareness is not the reason for low uptake and highlighted other factors they believed influenced the low number of BSGLM using PrEP, such as access and limited financial resources. Participants in all 4 FGDs explained that condom use is the expectation, even though BSGLM do not use them often. Numerous benefits of PrEP were mentioned across the FGDs, including having greater confidence in and security about sexual health, feeling a sense of sexual liberation, and improved relationships, although participants also acknowledged that PrEP use can negatively affect relationships primarily due to introducing feelings of mistrust. Participants also described that protecting sexual health is not a priority concern among some BSGLM.

FGD participants said that BSGLM in Charlotte displayed a range of readiness to initiate PrEP, from the pre-contemplation to preparation stages. Participants gave 2 reasons for why some BSGLM were in the pre-contemplation stage and have no plan to speak to a provider about PrEP: BSGLM are afraid of learning their HIV test results and are uncomfortable speaking with a provider about their sexuality. For BSGLM who were considering talking with a provider about PrEP but wanted more time to contemplate the decision—ie, the contemplation stage—FGDs participants shared that some BSGLM in this stage do not know how to gain access to PrEP care, they are lacking social support motivating them to seek PrEP care, they feel invincible and have not experienced any symptoms that warrant visiting a health care provider, and they were satisfied with the status quo of using condoms, though they were drawn to considering another effective prevention option. Similar access issues were mentioned when FGDs participants spoke about BSGLM men who they felt were in the preparation phase of PrEP readiness. Participants explained that these men need guidance on where to get PrEP as well as how to start the conversation about PrEP with a provider. Participants did not mention that BSGLM were in the action stage of PrEP readiness, where they had a plan to visit a health care provider soon to talk about PrEP.

Participants across the FGDs explained that perceptions on the severity of living with HIV has changed, primarily due to successful treatment and less stigma, and now many BSGLM no longer view HIV as a severe threat as many once did. Yet, participants also stressed that many BSGLM still fear an HIV diagnosis. As a result, participants explained that BSGLM generally avoid being tested for HIV.

Participants in all 4 FGDs expressed concern with the daily commitment to PrEP, stating that adding a new routine to existing daily routines is a deterrent for some BSGLM. The side effects of PrEP were also identified by participants in all FGDs as a main barrier to PrEP uptake. Participants described that BSGLM feared PrEP primarily as a result of television commercials, including both pharmaceutical company commercials and the PrEP lawsuit commercials. Participants explained that while the beginning of the pharmaceutical company commercials is motivating, they end with a long description of the potential side effects of PrEP, which participants state discourages BSGLM from wanting to use PrEP.

Reinforcing Factors

FGD participants spoke about the importance of having trust in a PrEP provider. In all 4 FGDs, participants described that some BSGLM have no or limited trust in providers that they do not know; however, participants in 2 FGD offered that they trusted and had confidence in their own providers. Participants also explained that not all BSGLM mistrust providers, but rather BSGLM mistrust people in general. Stigma-related concerns about providers’ potential reactions to men’s sexuality were expressed as reasons for the mistrust. Some FGD participants also described situations where a BSGLM they knew was treated unfairly by a provider because of his sexuality, while others said they had not heard of such experiences. Rapport building and confidentiality were stressed as factors critical to building and maintaining trust, and some FGD participants stated that BSGLM prefer a PrEP provider of color while others said the provider’s race was not important. FGD participants also described that some BSGLM experience stigma within gay and Black communities. Yet, some participants acknowledged that community support also exists.

Enabling Factors

FGD participants shared that BSGLM generally do not know how to access PrEP. Participants highlighted that BSGLM are hesitant in starting the process of seeking PrEP, and linked it to concerns about talking about their sexuality and HIV with providers but also to race and changes in family support. In addition, participants in all 4 FGDs perceived that awareness of the MCPI among BSGLM in Charlotte is low; many participants noted that they had not heard of it themselves.

Concerns about scheduling an initial PrEP visit was mentioned as a major barrier in all 4 FGDs. Participants described difficulties that BSGLM experience with getting time off from work and having busy lives that prevent them from seeking PrEP care. Participants in 3 FGDs also elaborated on concerns about costs, indicating that BSGLM perceive PrEP costs to be expensive and unattainable. Current and former PrEP users in the IDIs, however, explained that PrEP-related costs were currently not a barrier to PrEP use because either their private insurance or medication assistance programs covered their expenses, although several stated their inability to afford PrEP without this assistance.

Suggested Implementation Strategies

Social media was the most common approach suggested when asked how to promote PrEP uptake among BSGLM, mentioned in 3 of the 4 FGDs and by most IDI participants. Several IDI participants also suggested engaging influencers, and a few suggested providing information via other online platforms, such as websites; several also mentioned that they search online to find information on PrEP. In-person events, such as Pride and other public events, and the use of commercials were also mentioned by several IDI participants. The use of peer testimonials and PrEP navigators were perceived as helpful by participants in all FGDs and nearly all IDIs, and FGD participants gave advice on how best to work with influencers. Social media and in-person events were also commonly mentioned by IDI participants as strategies to increase awareness of the MCPI (see Supplement Table 1 in Section 3, Supplemental Digital Content).

Key Findings from the Organizational Assessments

All clinics reported they can accommodate more clients with their current staffing, although 2 clinics expressed concerns about administrative and laboratory costs. For 1 CBO, additional staff and funding are needed to adopt new strategies, and additional funding and staff may be needed by the other CBO depending on the scope of the strategies and how aligned they are to their current approaches. MCPI clinic partners described that they perceive the limited awareness of the MCPI program and clinics among BSGLM in Charlotte as a significant barrier to PrEP uptake.

Mapping Formative Research Findings to Determinants Constructs and Implementation Strategies

Figure 2 displays the key findings mapped to the CFIR8 determinants constructs and the ERIC implementation strategies.7 Based on the formative findings, we wanted to (1) increase awareness at the client level on how to access PrEP; (2) address other key client-level determinants identified in the findings, such as concerns about cost and provider trust, to increase comfort with accessing PrEP; and (3) make PrEP easier to access at the clinic level. For example, we linked the FGD findings that BSGLM find it difficult to schedule clinic appointments and perceive PrEP costs to be unattainable to CFIR’s “Intervention Characteristics” construct. We then linked (1) the scheduling determinant to the “Change Infrastructure” strategy of the ERIC implementation strategies (i.e., the partnering MCPI clinics will establish official “drop-in” days, with each clinic offering “drop-in” appointments on different days to extend PrEP access to BSGLM), and (2) the PrEP cost determinant to the “Use Financial Strategies” strategy (i.e., by partnering with and referring BSGLM to the MCPI clinics, which offer free PrEP services to clients without insurance). We linked the finding of limited awareness among BSGLM of how to initiate PrEP with the CFIR construct,8 “Knowledge/Beliefs about the Intervention” and the ERIC implementation strategy,7 “Provide Interactive Assistance” (i.e., by extending the CBO’s outreach to BSGLM via mobile apps and a web-based project landing page, linking BSGLM to the MCPI clinic of their choice). We also linked other formative research findings (e.g., BSGLM are hesitant to initiate PrEP and have limited trust in unfamiliar providers) to the “Knowledge/Beliefs about the Intervention” CFIR construct and then to 3 approaches within the “Engage the Consumer” ERIC implementation strategy: (1) posting of social media messages by CBOs; (2) influencers amplifying CBOs’ social media content while also creating their own content; and (3) peer role-modeling stories that are informed by Peers Reaching Out and Modeling Intervention Strategies (PROMISE) for high-impact prevention (HIP),14 an evidence-based intervention, and shared through the peers’ networks and by the CBOs. We will describe the details of the implementation strategies in a future manuscript after all development and pretesting activities are completed.

Discussion

We used collaborative community and researcher partnership processes coupled with evaluative and iterative strategies to achieve our immediate goals of identifying determinants and selecting community-driven implementation strategies designed to increase PrEP uptake among BSGLM. We identified numerous determinants on the uptake of PrEP among BSGLM that focus on the need to increase awareness among BSGLM on how to initiate PrEP and where to access it, as well as to make PrEP access easier at clinics. We selected 4 strategies to address the selected determinants: (1) use financial strategies, (2) change infrastructure (clinic), (3) engage the consumer, and (4) provide interactive assistance.

In evaluating the outcomes of our planning activities, guidance developed by the ISC3I15 was provided to the EHE award receipts on implementation outcomes to consider using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework16 and Proctor et al outcomes.17 For implementation preparedness activities, implementation outcomes on the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of the intervention (ie, PrEP) among sites (ie, clinic and CBO leadership) and implementers (ie, providers and CBO staff) are considered essential; outcomes on the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of the implementation strategies among sites and implementers are recommended. By choosing to partner with individuals who were already heavily engaged in PrEP-related efforts, we ensured that the intervention (i.e., PrEP) was acceptable, appropriate, and feasible to those who would be involved in implementing the subsequent evaluation. In addition, by using the “engaging” and “planning” strategies from the CFIR determinants process constructs,8 the implementation strategies we selected were considered acceptable, appropriate, and feasible to sites and implementers, prior to any formal evaluation, because sites and implementers contributed to their selection and development. We have recently completed additional FGDs with BSGLM to pretest the social media content and approaches, which will provide further evidence on the acceptability and appropriateness of the proposed “engage the consumer” implementation strategies—other recommended service effectiveness outcomes to assess.

Other studies among BSGLM men in the US South have also reported similar findings on the determinants we identified, specifically general awareness of PrEP among BSGLM,18 concerns about PrEP costs,18–20 limited awareness of how to access PrEP,18 condom optimism,21 and perceived helpfulness of testimonials by BSGLM.18 Intersectional stigma related to racial identity and sexual orientation22–24 and anticipated stigma19 has also been reported among studies with BSGLM. In our formative research, stigma-related concerns primarily focused on perceptions of future interactions with providers; hence, our implementation strategies promote clinics who currently provide PrEP care to BSGLM.

Our activities should be viewed within the context of their limitations, which primarily focus on the use of purposeful sampling for qualitative research and our inability to reach our targeted sample size of FGD and IDI participants. Details are described in Section 5 of the Supplemental Digital Content.

The end result of our planning activities will be a finalized PrEP-MECK logic model for piloting the implementation strategies, including implementation, service, and client outcomes, as well as a detailed study design for a pilot evaluation. Ultimately, by increasing uptake of PrEP among BSGLM, our project addresses the “prevent” pillar of the EHE initiative and has the potential to increase PrEP uptake and reduce HIV incidence in a key population at risk for HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants for sharing their perspectives and ideas with us. We also acknowledge the following individuals: (1) our partners in the Mecklenburg County PrEP Initiative: A. Bernard Davis, MBA (RAO Community Health), Faye Marshall (Quality Comprehensive Health Care and The PowerHouse Project), Tagbo J. Ekwonu, MD, AAHIVS (Eastowne Family Physicians), and J. Wesley Thompson, MHS, PA, AAHIVS (Amity Medical Group), who is also an investigator; (2) Patrice Marsh, formerly of RAIN, Inc, for contributing to the development of the “engage the consumer” content; (3) Sara LeGrand, PhD, for contributions during project planning, and (4) the UAB Center for AIDS Research EHE Implementation Science Consultation Hub for feedback and insight.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

This planning grant was supported by a NIH Administrative Supplement to the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (5P30 AI064518) as part of the CFAR/ARC Ending the HIV Epidemic Supplement Awards. None of the authors reported having any conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Previous Presentation/Dissemination of Research Findings: We presented a brief electronic poster at the National Ending the HIV Epidemic Meeting held virtually on April 14-15, 2021. Participants received a 1-page summary of the key findings.

Contributor Information

Amy Corneli, Department of Population Health Sciences and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Brian Perry, Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Johnny Wilson, RAIN, Inc, Charlotte, NC.

Susan Reif, Center for Health Policy and Inequalities Research, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC.

Chelsea Gulden, RAIN, Inc, Charlotte, NC.

Emily Hanlen-Rosado, Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Haley Cooper, Center for Health Policy and Inequalities Research, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC.

Jamilah Taylor, Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Summer Starling, Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

J. Wesley Thompson, Amity Medical Group, Charlotte, NC.

References

- 1.Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Issue Brief: HIV in the Southern United States. Published online 2019. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf

- 3.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. CFAR/ARC Ending the HIV Epidemic Supplement Awards. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/cfar-arc-ending-hiv-epidemic-supplement-awards

- 4.Overview: What is Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S.? HIV.gov. Published 2021. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview

- 5.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green L, Kreuter MK. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 4th ed. McGraw Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and Sick Role Behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):409–419. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prochaska J, DiClemente C. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing the Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Dow Jones/Irwin; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Sage Publications.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JD, Li DH, Rafferty MR. The Implementation Research Logic Model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PROMISE for HIP. Published May 5, 2021. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/treat/promise-for-hip/index.html

- 15.Implementation Science Coordination, Consultation, & Collaboration Initiative. HIV Implementation Outcomes Operationalization Guide – ISC3I. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://isc3i.isgmh.northwestern.edu/hivoutcomes/

- 16.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elopre L, Ott C, Lambert CC, et al. Missed Prevention Opportunities: Why Young, Black MSM with Recent HIV Diagnosis did not Access HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Services. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(5):1464–1473. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02985-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold T, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Chan PA, et al. Social, structural, behavioral and clinical factors influencing retention in Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) care in Mississippi. Caylà JA, ed. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas PD. A Qualitative Exploration of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Initiation Decision-Making Among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM): “It Definitely was a Process.” J Natl Black Nurses Assoc JNBNA. 2019;30(2):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lockard A, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, et al. Contrasting Self-Perceived Need and Guideline-Based Indication for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Young, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men Offered Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Atlanta, Georgia. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2019;33(3):112–119. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elopre L, McDavid C, Brown A, Shurbaji S, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM. Perceptions of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Young, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(12):511–518. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denson DJ, Gelaude D, Saul H, et al. “To Me, Everybody Is infected”: Understanding Narratives about HIV Risk among HIV-negative Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in the Deep South. J Homosex. 2021;68(6):973–992. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2019.1694338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers BG, Whiteley L, Haubrick KK, Mena LA, Brown LK. Intervention Messaging About Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Use Among Young, Black Sexual Minority Men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2019;33(11):473–481. doi: 10.1089/apc.2019.0139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.