Abstract

The Huanan market harbored many of the early COVID-19 cases in 2019 and is a key element to understanding the origin of the pandemic. Whether the initial animal-to-human transmission did occur at this market is still debated. Here we do not examine how SARS-CoV-2 virus was introduced at the market, but focus on how early cases may have been infected at the market. Based on available evidence, we suggest that several early infections at the Huanan market may have occurred via human-to-human transmission in closed spaces such as canteens, Mahjong rooms or toilets. We advocate for further studies to investigate this hypothesis.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Huanan market, Epidemiology, Retrospective contact tracing

Abbreviations: COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; WHO, World Health Organization

1. Introduction

To better understand the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to examine carefully the earliest COVID-19 cases in Wuhan and to try to reconstruct the chains of transmission. The earliest confirmed COVID-19 patients declared symptoms in December 2019 (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021). Among these December 2019 cases, about half were linked to Huanan Market (Worobey, 2021; Lu et al., 2020a). This market was one of the largest seafood wholesale markets in central China, located in a busy part of Wuhan city, about 800 m away from the Hankou railway station. About 10,000 people visited the market per day (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021).

Despite claims in the March 2021 WHO-China joint report (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021) that live wild mammals were not sold at the Huanan market, a survey (Xiao et al., 2021) later showed that they were, including raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides), which are potential transient hosts for severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronaviruses (SARS-r-CoVs) (Freuling et al., 2020). The exact role of the Huanan market in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear. Some scientists tend to think that an initial animal-to-human transmission occurred at this market (Worobey, 2021; Holmes et al., 2021; Garry, 2021; Worobey et al., 2022; Pekar et al., 2022) whereas others believe that the Huanan market was the location of an early ‘superspreading’ event and that SARS-CoV-2 probably infected people elsewhere and earlier (Chan and Ridley, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2022).

The Huanan seafood market underwent sanitary procedures and disinfection before closing permanently at 1am on January 1, 2020 (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021; Kang et al., 2020; Hessler, 2020). The closure, however, concerned only the first floor of the building, while the second floor, which housed eyeglass stores, remained open until 11 January 2020 (Hessler, 2020). Future plans for the Huanan market have not yet been issued (Zhang, 2021). In January–March 2020 researchers from China's Center for Disease Control and Prevention collected environmental samples and animal swabs in the Huanan market and the exact details of these sampling efforts were recently provided in a preprint in February 2022 (Gao et al., 2022) (Table S1). All animal samples were negative and 64 environmental samples collected inside the market, mostly from stalls and sewage wells, showed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The sequences of the virus present on surfaces were highly similar to the ones collected from patients from the market (Li et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2022). These positive samples may come from the patients themselves or from presumptive animals who contaminated them. In addition, a group of Beijing researchers were given a brief access to the Huanan market in February 2020 and they surveyed 80 environmental samples around animal-selling stalls and 22 environmental samples from cold storage sites for animal products. They found no positive sample for SARS-CoV-2 (Wu et al., 2021) (Table S1).

Epidemiological studies have found that SARS-CoV-2 transmission is more likely to occur indoors than outdoors, and that closed, poorly ventilated environments are major sites of contamination (Leclerc et al., 2020; Qian et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). In particular, toilets are notable places for SARS and COVID-19 contamination, through inhalation of viral particles and possibly contact with contaminated surfaces. Indeed, bathrooms are usually narrow unventilated rooms. A thorough study of the 310 passengers on a Milan-South Korea flight clearly identified a 28-year-old person who was infected in the bathroom on the flight where she took her mask off (Bae et al., 2020). Furthermore, multiple studies have detected large amounts of SARS-CoV-2 particles in the toilets of hospitals and homes (Ding et al., 2021; Amoah et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2020; Ong et al., 2020).

Here we review available epidemiological data about the Huanan market outbreak. Based on the spatial and temporal distribution of the initial positive cases at the market, we suggest that several early infections at the Huanan market may have occurred via human-to-human transmission, presumably in closed spaces. We discuss how further studies may investigate this hypothesis.

2. Analysis of available data

2.1. Early cases used to spend several hours in the market

Among the 53 early official COVID-19 cases with direct exposure to the Huanan market, 30 were vendors at fixed stalls in the market, 12 were important purchasers buying food materials at different stalls for hotels or restaurants, and 2 were deliverymen (Table 3 of WHO-China Joint Report Annexe (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021)). Passers-by and community residents who purchased food for their families in the market represented only 9 of these early COVID-19 cases (17%). One possibility is that the duration and frequency of exposure in the market correlate with infection and morbidity risks. Another is that the former group used shared closed rooms such as common activity rooms or toilets whereas the second group did not.

2.2. Initial cases were about 20–40 m apart in the market

The earliest cases were located in the west side of the market, and they were not extremely clustered spatially (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). Following the first detected case, the next five appeared a few days later, more than 20 m away in other market stalls (Fig. 2), some of them isolated by walls reaching up to the ceiling (Table S2). If animals were the initial source of the infection, such animals would probably have been present at a particular stall on the market, and they would have led to early contamination of persons located closer than 20–40 m. A 2020 study in a Chinese hospital revealed that the SARS-CoV-2 virus usually dispersed within a 4-m radius around patients (Guo et al., 2020). Transmission at 6–7 m distance was reported after a 1 h and 40 min bus ride in 2020 (Shen et al., 2020) but appeared to be very rare with the early SARS-CoV-2 variants (Hu et al., 2021). Experiments with ferrets showed that SARS-CoV-2 air transmission between animals occurs within a short distance (Kim et al., 2020). In large indoor spaces such as the Huanan market, transmission was expected to occur within 1–4 m from the contagious individual.

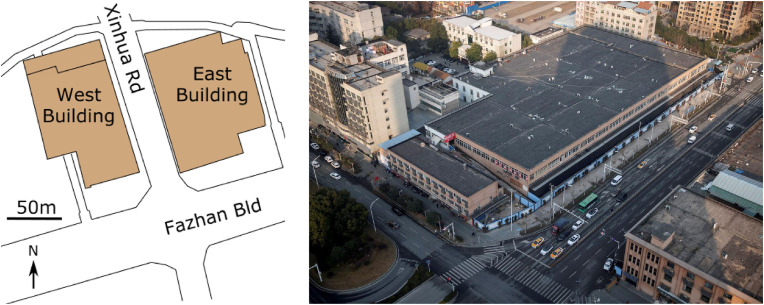

Fig. 1.

The Huanan seafood market. (A) Map of the West and East buildings of the Huanan market, Wuhan, China. The first cases were detected in the West building. (B) Aerial view of the West building on 15 January 2021. REUTERS/Thomas Peter.

Fig. 2.

Weekly spatial distribution of early COVID-19 cases in the Huanan market. The first two weeks (until 2019-12-13 and until 2019-12-20) are represented from left to right. Note the low resolution of the figure as in the WHO-China joint report. Patients who developed symptoms on week 2 are 20–40 m away from the week 1 patient. Even if the detected week 1 patient is not located at the source of the contamination, patients from week 2 are too far apart to be consistent with one or two sources of SARS-CoV-2. From (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021) (p. 181, Annexe).

2.3. Air dynamics within the market are unknown

The market ventilation system had been closed when live poultry trade was stopped following the outbreak of avian influenza (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021), so that the market was overall poorly ventilated. However, a large North-South alley in the West building allowed the passage of small trucks, with a ceiling about 7 m from the ground (Supplementary Information). Unfortunately, no analysis of the dynamics of air distribution within the West building is available. It would be useful to model air flows within the market to test whether they can explain the spatial distribution of early cases.

2.4. The early cases shared closed spaces at the market

The first Huanan market associated patient is a 57-year-old woman who fell sick on 10 December 2019 and who used to sell shrimp. Her interview by the Wall Street Journal reveals that she was using the toilets of the Huanan market: she “thinks she might have been infected via the toilet she shared with the wild meat sellers and others on the market's west side” (Page et al., 2020). In addition, rumors circulated that some of the early patients were playing Mahjong in a small unventilated parlor located next to the public toilet (Hessler, 2020) and several vendors appeared to eat in neighboring canteens (Joint WHO-China Study Team, 2021). The so-called “chess and card rooms,” are usually packed and poorly ventilated spaces where elderly people gather to play. Such locations were important sites of SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks in China in 2020–2021 and thousands of them were shut down in 2020–2021 to limit the spread of the virus (Bloomberg News, 2021). It is therefore possible that some of the early cases infected each other not at the market stalls but in smaller spaces.

3. Discussion

Given that the market had about 10,000 visitors per day, it is interesting to note that the majority of the early cases associated with the market were vendors. This suggests that infection required long or repeated exposure to the animal/human source in the early days of the outbreak, or that most early transmissions occurred from human to human between vendors at their work space, possibly as they shared facilities.

The SARS-CoV-2 sequences from the market patients are almost identical. Epidemiological data are consistent with a single point of introduction of the virus at the market, which is compatible with a zoonotic origin, but does not preclude other possibilities such as a vendor infected outside of the market. Despite extensive sampling (Table S1), no infected animal has been found at the market.

The spatial scattering of early cases in the market (Fig. 2) is not indicative of direct aerosol transmission from a unique source. We suggest investigating further the possibility that the early contaminations at the market were due to the use of common areas such as toilets or canteens. How many restrooms were there in the market? Were they ventilated? Could they be a place for COVID-19 transmission? Were the toilets public or accessible to vendors only? What were the other activity rooms where market people gathered? Questionnaires to Huanan vendors and purchasers would help for elaborating possible scenarios of transmission, by asking which persons were regular users of the washrooms, which restrooms they used, on which days, etc. Other possible epidemiological links between the early market cases should also be scrutinized: did they share other activities (dinner, board games, card games, etc.) either at the Huanan market or at other locations?

In addition, the exact details of the animal and environmental samples that were examined for the presence of SARS-CoV-2, both positive and negative, should be made available and an analysis of air flows within the market would help to infer possible routes of air contamination from localized sources.

In the early days of the pandemic in 2020, exemplary, meticulous COVID-19 case and contact identifications were performed by epidemiologists in China and several landmark papers were published [see for example (Guo et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Jiehao et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2020b; Bai et al., 2020)]. These helped the world to better understand the characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 virus transmission. An analytical epidemiological study among vendors and shoppers, with detailed mapping of exposure and contamination factors at the market, and type of products and animals sold, would help to shed light on the possible paths of contamination for the early market cases.

Even if several early market outbreak cases may turn out to be explained by human-to-human transmission, we note that it remains unclear how the first person at the Huanan market was contaminated and whether the market was a site of animal-to-human contamination. However, taking into account the exact location of the early patients in the market can help to refine scenarios about the origin of the pandemic. The earliest detected case is located in a stall that is a few dozens of meters north compared to the presumed animal source hotspot highlighted in the recent Worobey et al. preprint (Worobey et al., 2022). If this patient was infected at the market by an animal, then either the place highlighted by Worobey et al. for animal-to-human contamination is incorrect and should be close to this first patient or this early case somehow contracted the virus around the distant stall highlighted by Worobey et al. Alternatively, this earliest case at the market was infected by humans and the initial introduction of the virus into the human population occurred earlier.

If a cluster of patients located a few meters away from each other had been detected at the market in the early days of the pandemic, it would be natural to suggest an animal source hotspot and animal-to-human contamination at the market. However, the first detected patients are relatively far from each other. We suggest here that they infected each other in common rooms such as toilets. Our analysis therefore decreases the possibility of substantial animal-to-human contamination at the market.

Author contributions

FdR and VCO examined available data, VCO wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

VCO received funding for a research project entitled “Elucidating the proximal origin(s) of the SARS-Cov2” (Labex WhoAmI, Excellence Initiative, University of Paris, September 2021–August 2023). We thank all participants of the monthly interdisciplinary workshops to elucidate the origins of SARS-CoV-2 and the anonymous researcher @babarlelephant for help with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113702.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Amoah I.D., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA on contact surfaces within shared sanitation facilities. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2021;236:113807. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S.H., et al. Asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on evacuation flight. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:2705. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.203353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg News . 2021. China Mahjong Dens Were Superspreader Sites, Spurring Crackdown. [Google Scholar]

- Chan A., Ridley M. Harper Collins; 2021. Viral. The Search for the Origin of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., et al. Toilets dominate environmental detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in a hospital. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;753:141710. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freuling C.M., et al. Susceptibility of raccoon dogs for experimental SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:2982. doi: 10.3201/eid2612.203733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G., et al. Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in the environment and animal samples of the Huanan seafood market. Nat. Portf. Res. Sq. 2022 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1370392/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garry R.F. Virological; 2021. Early appearance of two distinct genomic lineages of SARS-CoV-2 in different Wuhan wildlife markets suggests SARS-CoV-2 has a natural origin.https://virological.org/t/early-appearance-of-two-distinct-genomic-lineages-of-sars-cov-2-in-different-wuhan-wildlife-markets-suggests-sars-cov-2-has-a-natural-origin/691 [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.-D., et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1586. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessler P. 2020. Nine Days in Wuhan, the Ground Zero of the Coronavirus Pandemic. New Yorker. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.C., et al. The origins of SARS-CoV-2: a critical review. Cell. 2021;184(19):4848–4856. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., et al. Environmental contamination by SARS-CoV-2 of an imported case during incubation period. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140620. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M., et al. Risk of coronavirus disease 2019 transmission in train passengers: an epidemiological and modeling study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;72:604–610. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiehao C., et al. A case series of children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection: clinical and epidemiological features. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:1547–1551. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint WHO-China Study Team . World Health Organisation; 2021. WHO-convened Global Study of Origins of SARS-CoV-2: China Part". [Google Scholar]

- Kang D., Cheng M., McNeil S. Assoc. Press; 2020. China Clamps Down in Hidden Hunt for Coronavirus Origins. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-I., et al. Infection and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:704–709. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc Q.J., et al. What settings have been linked to SARS-CoV-2 transmission clusters? Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5 doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15889.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lai S., Gao G.F., Shi W. The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., et al. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020;582:557–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet Lond. Englera. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., et al. COVID-19 outbreak associated with air conditioning in restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1628. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong S.W.X., et al. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA. 2020;323:1610–1612. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page J., Fan W., Khan N. How it all started: China’s early coronavirus missteps. Wall Str. J. 2020 https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-it-all-started-chinas-early-coronavirus-missteps-11583508932 [Google Scholar]

- Pekar J.E., et al. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Emergence Very Likely Resulted from at Least Two Zoonotic Events. Zenodo Prepr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H., et al. Indoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Indoor Air. 2021;31:639–645. doi: 10.1111/ina.12766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., et al. Community outbreak investigation of SARS-CoV-2 transmission among bus riders in eastern China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:1665–1671. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Gu J., An T. The emission and dynamics of droplets from human expiratory activities and COVID-19 transmission in public transport system: a review. Build. Environ. Times. 2022;109224 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey M. Dissecting the early COVID-19 cases in Wuhan. Science. 2021;374:1202–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.abm4454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey M., et al. 2022. The Huanan Market was the Epicenter of SARS-CoV-2 Emergence. Zenodo Prepr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., et al. A comprehensive survey of bat sarbecoviruses across China for the origin tracing of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Res. Sq. 2021 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwac213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Newman C., Buesching C.D., Macdonald D.W., Zhou Z.-M. Animal sales from Wuhan wet markets immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:11898. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Glob. Times; 2021. Wuhan's Huanan Market "Won't Be Demolished Soon"; No More Valuable Info on Virus Origins Available in It. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.