Abstract

The conclusions of the EFSA following the peer review of the initial risk assessments carried out by the competent authorities of the rapporteur Member States, the United Kingdom (former) and France (after withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU), for the pesticide active substance isoflucypram. The context of the peer review was that required by Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council. The conclusions were reached on the basis of the evaluation of the representative use of isoflucypram as a fungicide on wheat, rye, triticale, barley and oats (field use). The reliable endpoints, appropriate for use in regulatory risk assessment, are presented. Missing information identified as being required by the regulatory framework is listed. Concerns are identified.

Keywords: isoflucypram, peer review, risk assessment, pesticide, fungicide

Summary

Isoflucypram is a new active substance for which, in accordance with Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, the rapporteur Member State (RMS), the United Kingdom (former RMS replaced by France after withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU), received an application from Bayer AG on 12 February 2018 for approval. In addition, in accordance with Article 8(1)(g) of the Regulation, Bayer AG submitted applications for maximum residue levels (MRLs) as referred to in Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 396/2005. Complying with Article 9 of the Regulation, the completeness of the dossier was checked by the RMS and the date of admissibility of the application was recognised as being 11 May 2018.

An initial evaluation of the dossier on isoflucypram was provided by the RMS (the United Kingdom, replaced by France after withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU) in the draft assessment report (DAR) and subsequently, a peer review of the pesticide risk assessment on the RMS evaluation was conducted by EFSA in accordance with Article 12 of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009. The following conclusions are derived.

The uses of isoflucypram applied by foliar spraying according to the representative uses as a fungicide on cereal crops (wheat, triticale, rye, barley and oats), as proposed at EU level result in a sufficient fungicidal efficacy against the target diseases caused by wide range of fungi.

The assessment of the data package revealed no issues that could not be finalised or that need to be included as critical areas of concern with respect to of identity, physical and chemical properties and analytical methods.

In the section mammalian toxicology, two critical areas of concern have been identified (with related data gaps). The first one is related to the fact that the proposed content of the relevant impurity BCS‐AA10447 in the technical specification is not supported from the toxicology point of view, and therefore, the technical material used in the toxicity studies cannot be considered as representative of the proposed technical specification. The second one is related to the fact that the groundwater metabolite M12 is considered toxicologically relevant in the absence of data to demonstrate that it does not share the same reproductive toxicity potential than isoflucypram (classified as Repr 2 H361f).

In residue section, rotational and processing crops and livestock assessment should be regarded as provisional due to the lack of genotoxicity data for the metabolites M50, M66, M67 and M77 and for storage stability for M01 and M06. Although the consumer exposure is expected to be low, the overall consumer risk assessment should be regarded as not finalised pending the toxicological data on the relevant metabolites. The data available on environmental fate and behaviour were sufficient to carry out the required environmental exposure assessments at EU level for the representative uses. For these representative uses, all the FOCUS groundwater scenarios were indicated to have 80th percentile annual average recharge concentrations moving below 1 m, above the parametric drinking water limit of 0.1 µg/L for the groundwater relevant metabolite M12. This resulted in the identification of a critical area of concern. Should risk managers choose to introduce risk management based on restricting use to aquifers overlaid predominantly by topsoils with pH(CaCl2) above 6.6, then the available modelling indicated that M12 annual average recharge concentrations moving below 1 m will be below the parametric drinking water limit, under the soil texture and climate conditions represented by all these FOCUS scenarios.

Pending the outcome of the data gap on the exact composition of the representative product, information whether the representative formulation was used in the ecotoxicity studies is needed. Additional data on the impact of impurities present in the proposed specification but not in the batches used in the ecotoxicity studies are also needed. A high risk was identified for fish in two scenarios. An assessment that could not be finalised was concluded for the chronic risk to bees.

Based on the available data and assessment, Isoflucypram is not considered to meet the criteria for endocrine disruption for the EAS modalities for humans and is considered unlikely to meet the criteria for endocrine disruption for the EAS modalities for the non‐target organisms. The assessment of the endocrine disrupting properties of isoflucypram for the T‐modality for humans and non‐target organisms according to point 3.6.5 and 3.8.2 of Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, as amended by Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/605 could not be finalised.

Background

Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council 1 (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Regulation’) lays down, inter alia, the detailed rules as regards the procedure and conditions for approval of active substances. This regulates for the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) the procedure for organising the consultation of Member States and the applicant(s) for comments on the initial evaluation in the draft assessment report (DAR), provided by the rapporteur Member State (RMS), and the organisation of an expert consultation, where appropriate.

In accordance with Article 12 of the Regulation, EFSA is required to adopt a conclusion on whether an active substance can be expected to meet the approval criteria provided for in Article 4 of the Regulation (also taking into consideration recital (10) of the Regulation) within 120 days from the end of the period provided for the submission of written comments, subject to an extension of 30 days where an expert consultation is necessary, and a further extension of up to 150 days where additional information is required to be submitted by the applicant(s) in accordance with Article 12(3).

Isoflucypram is a new active substance for which, in accordance with Article 7 of the Regulation, the RMS, the United Kingdom initially replaced by France (hereinafter referred to as the ‘RMS’), received an application from Bayer AG on 12 February 2018 for approval of the active substance isoflucypram. In accordance with Article 8(1)(g) of the Regulation, Bayer AG submitted applications for maximum residue levels (MRLs) as referred to in Article 7 of Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 2 . Complying with Article 9 of the Regulation, the completeness of the dossier was checked by the RMS and the date of admissibility of the application was recognised as being 11 May 2018.

The RMS provided its initial evaluation of the dossier on isoflucypram in the DAR, which was received by EFSA on 29 March 2019 (United Kingdom, 2000a, 2000b, 2011, 2019). The DAR included a proposal to set MRLs, in accordance with Article 11(2) of the Regulation. The peer review was initiated on 12 August 2019 by dispatching the DAR to the Member States and the applicant, Bayer AG, for consultation and comments. EFSA also provided comments. In addition, EFSA conducted a public consultation on the DAR. The comments received were collated by EFSA and forwarded to the RMS for compilation and evaluation in the format of a reporting table. The applicant was invited to respond to the comments in column 3 of the reporting table. The comments and the applicant response were evaluated by the RMS in column 3.

The need for expert consultation and the necessity for additional information to be submitted by the applicant in accordance with Article 12(3) of the Regulation were considered in a telephone conference between EFSA, the RMS and co‐RMS on 16 January 2020. On the basis of the comments received, the applicant’s response to the comments and the RMS’s evaluation thereof, it was concluded that additional information should be requested from the applicant, and that EFSA should conduct an expert consultation in the areas of mammalian toxicology, residues, environmental fate and behaviour and ecotoxicology.

The outcome of the telephone conference together with EFSA’s further consideration of the comments is reflected in the conclusions set out in column 4 of the reporting table. All points that were identified as unresolved at the end of the comment evaluation phase and which required further consideration, including those issues to be considered in an expert consultation, were compiled by EFSA in the format of an evaluation table.

The conclusions arising from the consideration by EFSA, and as appropriate by the RMS, of the points identified in the evaluation table, together with the outcome of the expert consultation and the written consultation on the assessment of additional information, where these took place, were reported in the final column of the evaluation table.

In accordance with Article 12 of the Regulation, EFSA should adopt a conclusion on whether isoflucypram can be expected to meet the approval criteria provided for in Article 4 of the Regulation, taking into consideration recital (10) of the Regulation.

A final consultation on the conclusions arising from the peer review of the risk assessment and on the proposed MRLs took place with Member States via a written procedure in March 2022.

This conclusion report summarises the outcome of the peer review of the risk assessment on the active substance and the representative formulation evaluated on the basis of the representative use of isoflucypram as a fungicide on wheat, rye, triticale, barley and oats (field use) as proposed by the applicant. In accordance with Article 12(2) of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, risk mitigation options identified in the DAR and considered during the peer review, if any, are presented in the conclusion.

Furthermore, this conclusion also addresses the requirement for an assessment by EFSA under Article 12 of Regulation (EC) No 396/2005, provided that the active substance will be approved under Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 without restrictions affecting the residue assessment. In the event of a non‐approval of the active substance or an approval with restrictions that have an impact on the residue assessment, the MRL proposals, if any, from this conclusion might no longer be relevant and a new assessment under Article 12 of Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 will be required.

A list of the relevant end points for the active substance and the formulation is provided in Appendix B. In addition, the considerations as regards the cut‐off criteria for isoflucypram according to Annex II of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 are summarised in Appendix A.

A key supporting document to this conclusion is the peer review report (EFSA, 2022), which is a compilation of the documentation developed to evaluate and address all issues raised in the peer review, from the initial commenting phase to the conclusion. The peer review report comprises the following documents, in which all views expressed during the course of the peer review, including minority views, where applicable, can be found:

the comments received on the DAR;

the reporting table (16 January 2020);

the evaluation table (27 April 2022);

the reports of the scientific consultation with Member State experts;

the comments received on the assessment of the additional information;

the comments received on the draft EFSA conclusion.

Given the importance of the DAR, including its revisions (France, 2022), and the peer review report, both documents are considered as background documents to this conclusion and thus are made publicly available.

It is recommended that this conclusion and its background documents would not be accepted to support any registration outside the EU for which the applicant has not demonstrated that it has regulatory access to the information on which this conclusion report is based.

The active substance and the formulated product

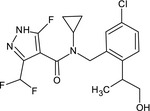

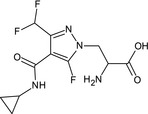

Isoflucypram is an ISO common name for N‐(5‐chloro‐2‐isopropylbenzyl)‐N‐cyclopropyl‐3‐(difluoromethyl)‐5‐fluoro‐1‐methyl‐1H‐pyrazole‐4‐carboxamide (IUPAC).

The representative formulated product for the evaluation was ‘Isoflucypram EC 50’, an emulsifiable concentrate (EC) containing 50 g/L isoflucypram. However, a clarification on the detailed composition of the representative formulation is needed and whether this representative formulation was used for data generation studies (data gap, see Section 10). The representative uses evaluated were foliar spray applications on cereal crops (wheat, triticale, rye, barley and oats) for the control of a range of diseases caused by fungi such as Mycosphaerella graminicola, Puccinia recondita, Puccinia striiformis, Pyrenophora tritici‐repentis, Rhynchosporium secalis, Pyrenophora teres, Puccinia hordei, Ramularia collocygni, Puccinia coronata and Pyrenophora avenae. Full details of the GAPs can be found in the list of end points in Appendix B.

Data were submitted to conclude that the uses of isoflucypram according to the representative uses proposed at EU level result in a sufficient fungicidal efficacy against the target organisms, following the guidance document SANCO/10054/2013‐rev. 3 (European Commission, 2013).

Conclusions of the evaluation

1. Identity, physical/chemical/technical properties and methods of analysis

The following guidance documents were followed in the production of this conclusion (European Commission, 2000a, 2000b, 2010, 2013).

The proposed specification for isoflucypram is based on batch data from pilot scale production. The proposed minimum purity of the technical material is 960 g/kg. N‐cyclopropyl‐3‐(difluoromethyl)‐5‐fluoro‐1‐methyl‐N‐{[2‐(propan‐2‐yl)phenyl]methyl}‐1H‐pyrazole‐4‐carboxamide (BCS‐CN45153) and 3‐(difluoromethyl)‐5‐fluoro‐1‐methyl‐1H‐pyrazole‐4‐carboxylic acid (BCS‐CR73065) are considered as relevant impurities with maximum levels of 1.0 and 5.0 g/kg, respectively. N,N‐dimethylcyclohexanamine (BCS‐AA10447) is also a relevant impurity; however, the maximum level proposed in the specification (4 g/kg) is not supported from the (eco)toxicology point of view (see Sections 2 and 5). As a consequence, the batches used in the (eco)toxicological assessment do not support the proposed specification (see Sections 2 and 5). An FAO specification is not available for isoflucypram. It should be noted that according to Regulation (EU) 283/2013 3 information on the analytical profile of batches should be provided again, once industrial scale production methods and procedures have stabilised.

The main data regarding the identity of isoflucypram and its physical and chemical properties are given in Appendix B. However, data gaps for spectral data and the content of the relevant impurities BCS‐CR73065 and BCS‐AA10447 before and after storage of the plant protection product are identified.

Adequate methods are available for the generation of pre‐approval data required for the risk assessment. Methods of analysis are available for the determination of the active substance in the technical material and representative formulation. Method for analysis is available for determination of the relevant impurity BCS‐CN45153 in the representative formulation. Methods for analysis of the other two relevant impurities (BCS‐CR73065 and BCS‐AA10447) in the representative formulation are missing (data gap).

Isoflucypram residue can be monitored in food and feed of plant origin by high‐performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC‐MS/MS) with a limit of quantification (LOQ) of 0.01 mg/kg in all commodities. Isoflucypram residue in food of animal origin can be determined by QuEChERS method with HPLC–MS/MS with LOQ of 0.005 mg/kg in milk and 0.01 mg/kg in the other animal matrices (eggs, muscle, fat, liver, kidney). It should be noted that the efficiency of the extraction procedure used for eggs is not sufficient; however, for the representative use residue above LOQ was not observed in eggs; therefore, additional data are not required. A validated HPLC‐MS/MS method exists for the determination of isoflucypram residue in honey with an LOQ of 0.01 mg/kg.

Isoflucypram residues in soil, water and air can be monitored by HPLC‐MS/MS with LOQs of 0.001 mg/kg, 0.0625 µg/L and 4.2 µg/m3, respectively. However, the residue definition for monitoring in ground water was concluded as isoflucypram and M12; therefore, a data gap for a monitoring method for determination of M12 in water is identified.

HPLC‐MS/MS method can be used for monitoring of isoflucypram and M11 residues in body fluids (plasma) with LOQ of 0.05 mg/L. However, residue definition for monitoring in body fluids (plasma) was concluded as isoflucypram, M11 and M58, as a consequence a data gap for monitoring method for M58 in body fluids is set. Isoflucypram residue in body tissues can be determined by the monitoring method for animal products.

2. Mammalian toxicity

The toxicological profile of the active substance isoflucypram and its metabolites was discussed at the Pesticides Peer Review Experts’ Teleconference 64 in November 2021 and assessed based on the following guidance documents (European Commission, 2003,2012; EFSA 2014b; EFSA PPR Panel, 2012; ECHA, 2017).

The toxicological profile of isoflucypram relied upon toxicity studies performed with a technical material that was not representative of the proposed technical specification for the active substance and associated impurities. This is because the proposed content (4 g/kg) of the relevant impurity BCS‐AA10447 in the technical specification is not supported from the toxicology point of view leading to a data gap and critical area of concern. Impurities BCS‐CN45153 and BCS‐CR73065 are also relevant impurities, being their maximum content 1.0 and 5.0 g/kg, respectively.

The analytical methods used in the toxicity studies were considered fit‐for‐purpose.

In the toxicokinetic studies, oral absorption was estimated to be greater than 80%. There was no evidence for accumulation. Widely distributed, isoflucypram is predominantly excreted through the bile. Isoflucypram is extensively metabolised. Available comparative in vitro metabolism study suggests that the metabolic pathway in the different species was similar; however, the study had some limitations. 4

Isoflucypram belongs to the chemical family of Succinate DeHydrogenase Inhibitors (SDHI), which rely on the inhibition of the fungal enzyme succinate dehydrogenase (mitochondrial complex II). Since this target is also present in mammals including humans, the experts at the Teleconference 64 agreed that as a first step, the comparative in vitro metabolism of isoflucypram should be repeated in human and animal hepatocytes, using two different radiolabels, with the objective to better identify and quantify main metabolites (data gap). Thereafter, isoflucypram and major human metabolites could be tested in vitro for their potential to inhibit SDH (complex II) and other complexes which are involved in the electron transport chain (ETC) (data gap). The experts agreed that SDH/ETC inhibition requires further consideration. However, the experts acknowledged that the set of required pivotal toxicological studies with isoflucypram did not provide evidence of effects that could be attributed to SDH inhibition as the mechanism of action. Therefore, the experts considered that, currently, there is no reason to preclude the toxicological evaluation of isoflucypram in the context of the current regulatory requirements. 5

The proposed residue definition for body fluids is isoflucypram and the metabolites M11 and M58. It is noted that this residue definition is applicable only to plasma (i.e. parent compound was not detected in urine and no major metabolite was present either in urine).

In the acute toxicity studies, isoflucypram has low acute toxicity when administered orally or dermally and moderate acute toxicity when administered by inhalation to rats (Acute Tox 4). It is not a skin or eye irritant but a skin sensitiser. Although an in vitro study is not required for isoflucypram (isoflucypram does not absorb electromagnetic radiation in the range 290–700 nm) isoflucypram was not phototoxic in the available in vitro study.

In repeated oral toxicity studies, reduced body weight gain (rats, mice and dogs) and clinical chemistry findings (rats, mice and dogs) were observed. The target organs of toxicity were liver (rats, mice and dogs), thyroid (rats) and kidney (rats and mice). The dog was the most sensitive species after short‐term exposure and the rat after long‐term exposure. The relevant short‐term oral NOAEL is 4.2 mg/kg body weight (bw) per day (90‐day and 1‐year dog study). The relevant long‐term oral NOAEL is 6.27 mg/kg bw per day (2‐year rat study). It is noted that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was not reached and that higher doses should have been used in the long‐term/carcinogenicity study in rats. The substance showed no carcinogenic potential in rats and mice up to the highest tested doses. According to ECHA RAC, classification was not warranted due to inconclusive data (ECHA RAC, 2020).

Based on available genotoxicity studies, isoflucypram is unlikely to be genotoxic.

In the multigeneration reproductive toxicity studies, delayed vaginal opening and decreased gestation length triggered the reproductive toxicity NOAEL of 34.1 mg/kg bw per day. The agreed parental and offspring NOAELs are 34.1 mg/kg bw per day. It is noted that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was not reached in the multigeneration reproductive toxicity study. According to ECHA RAC, classification as Repr 2 H361f was triggered for isoflucypram (ECHA RAC, 2020). In the developmental toxicity studies, there was no evidence of teratogenicity, and the relevant maternal NOAELs are 125 mg/kg bw per day for the rat and 10 mg/kg bw per day for the rabbit, respectively. The developmental NOAELs are 25 and 500 mg/kg bw per day, for the rat and the rabbit, respectively.

Isoflucypram did not show potential for neurotoxicity and immunotoxicity in standard toxicity studies nor neurotoxicity in the acute neurotoxicity study in rats.

The agreed acceptable daily intake (ADI) for isoflucypram is 0.04 mg/kg bw per day, based on the relevant short‐term NOAEL of 4.2 mg/kg bw per day in the 90‐day and 1‐year studies in dogs based on reduced body weight gain, liver toxicity (hypertrophy) and clinical chemistry changes at 17.6 mg/kg bw per day. An uncertainty factor of 100 was applied. The experts considered that the margin of safety to the highest tested dose in the rat carcinogenicity would be 465 in males and 1,165 in females, reassuring that the ADI would be protective enough regardless the limitation of the dose selected in the rat carcinogenicity study.

The agreed systemic acceptable operator exposure level (AOEL) is 0.04 mg/kg bw per day, on the same basis as the ADI, and without correction for oral absorption.

The agreed acute reference dose (ARfD) is 0.1 mg/kg bw based on the maternal NOAEL of 10 mg/kg bw per day for the early and significant onset of decrease body weight gain at 70 mg/kg bw per day in the developmental toxicity study in rabbits. An uncertainty factor of 100 was applied.

The agreed systemic acute acceptable operator exposure level (AAOEL) is 0.1 mg/kg bw, on the same basis as the ARfD, and without correction for oral absorption.

The RMS estimated operator, worker, bystander and resident exposure using the EFSA Guidance (EFSA, 2014b) and considering the agreed AOEL and AAOEL values and dermal absorption values of isoflucypram in ‘Isoflucypram EC50’ of 4.4% for the concentrate and of 6.3% for the dilution as input values.

Considering the representative uses with ‘Isoflucypram EC50’ as fungicide in cereals, the estimated operator exposure was below the AOEL and AAOEL (maximum 45% of the AAOEL) without the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) during mixing and loading and application. Bystander and resident exposure estimates were below the AOEL and AAOEL (maximum 6.28% of the AOEL; child resident) with use of a default minimal buffer zone of 2–3 m. Worker exposure was also below the AOEL (1.65% of the AOEL) without the use of PPE.

Regarding metabolites, found as residues (in livestock and or crops, see Section 3), or in groundwater (see Section 4), experimental data were only available for metabolite M12. For other metabolites, the assessment was based on absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) and toxicokinetic data with parent compound, assessment of structural similarities to parent compound and QSAR analysis for genotoxicity.

The groundwater metabolite M12, occurring above 0.1 µg/L (see Section 4), is unlikely to be genotoxic based on experimental data. Since no data are available to demonstrate that it does not share the same reproductive toxicity potential than isoflucypram (classified as Repr 2 H361f (ECHA RAC, 2020)), M12 has to be considered as a toxicologically relevant groundwater metabolite (critical area of concern).

For M01, M02, M06, M11 and M12, there are close structural similarities to the parent compound and negative genotoxicity QSAR predictions. In addition, plasma levels of these metabolites in the 2‐year study in rats and/or in other toxicity studies were similar or higher than those of the parent. Therefore, the toxicity of these metabolites is covered by the toxicity data of the parent and if a risk assessment would be required, the reference values of isoflucypram could be used. This conclusion also applies to their respective conjugates (conjugates of M01: M18, M19, M21; conjugates of M02: M20, M22; conjugates of M06: M37, M41).

For M07, although there is no information on relative levels in rat plasma compared to the parent, there is close structural similarity to the parent compound and M06 and overall negative genotoxicity QSAR predictions. The reference values of M06, i.e. of the parent compound, could be used. This conclusion also applies to the conjugate of M07, M36.

For M10, there is close structural similarity to the parent compound and M12 and overall negative genotoxicity QSAR predictions. The reference values of M12, i.e. of the parent compound, could be used.

M58 is a major metabolite of isoflucypram (found in rat and mouse plasma collected after repeated dosing with parent, at higher concentrations). Reference values of isoflucypram could be used.

For M49, there is close structural similarity to M58 with similar genotoxicity predictions. Reference values of M58, i.e. of the parent compound, could be used.

For M50, M66, M67, M77, there is a potential concern for genotoxicity based on positive genotoxicity QSAR predictions (data gap).

3. Residues

The assessment in the residue section is based on the following guidance documents (OECD, 2009, 2000a, 2000b, 2011, 2019; European Commission, 2011; JMPR, 2004, 2007).

Isoflucypram was discussed in Pesticide Peer Review Experts’ Teleconference 66 (22–23 and 25–26 November 2021).

Primary metabolism has been sufficiently investigated with pyrazole and phenyl‐labelled isoflucypram in fruit crops (tomato), cereals (wheat), oilseeds (oilseed rape and soyabean) following foliar application and in root crops (potatoes) via seed treatment. The dose rate of the study covers the representative use in cereals. Isoflucypram was the major compound in all edible part of the crops (max 93% TRR in wheat grain, 98% TRR in tomato fruits, etc.) and in cereals feed items (up to 63% TRR in straw and 55% TRR in hay). Other relevant compounds found in relative and/or absolute amount were M01 and M06 free and conjugates in wheat straw and hay, M44, M45, M46, M47, M48 in soyabean forage and hay and M58 in potato tuber.

In the submitted field trials on cereals, M01 and M06 (free and conjugates) were found in grain at levels either comparable with the parent or higher. Since the observed metabolic distribution pattern among the crop groups is different and residue trials to confirm or not the metabolic pattern are available only in cereals during the meeting, experts decided to set the residue definition for risk assessment as sum of isoflucypram, M01 and its conjugates, M06 and conjugates expressed as isoflucypram limited to cereals only, following foliar application. Isoflucypram was proposed as residue definition for monitoring for all crops group following foliar application.

Two confined rotational crop studies with pyrazole and phenyl‐labelled isoflucypram were performed on turnip, Swiss chard and wheat with an application rate that covers the PEC accumulation of the GAPs. The metabolic pattern is also complex, not similar to primary crops, with the occurrence of several compounds (M49, M52, M54, M57, M62, M66, M67 and M69) found above 10% of TRRs. Parent was found at 17% TRRs only in wheat forage. It was noted that for the relevant metabolites M66 (max 26% TRR in wheat forage) and M67 (for 13% TRR in wheat grain), a potential concern for genotoxicity was identified and needs to be further investigated (data gap in Section 2 leading to consumer risk assessment not finalised). From the above‐mentioned metabolites found relevant in metabolism studies, M52 was found about 0.01 mg/kg in Swiss chard (0.011 mg/kg). A decrease of residues from the first to the third PBI is observed.

Four available rotational field trials were conducted on carrots/turnip, lettuce and barley at the maximum seasonal rate of the representative GAP and analysed for isoflucypram and M49. No residues above 0.01 mg/kg of isoflucypram and M49 were found the investigated crops.

Considering the overall data from rotational crops (metabolism and field trials) and missing toxicological data on M66 and M67, the experts decided to apply on a provisional basis the same residue definitions as for the primary crops. 6 It should also be noted that the assessment covers only the representative GAPs, and in case of extended uses, the inclusion of other metabolites in the residue definitions for rotational crops might need to be reconsidered.

Stability of isoflucypram and M49 during storage at −18°C was demonstrated for 25 months in different crop categories while for M01 and M06 stability was demonstrated only in wheat for 6 months (see details in Appendix B). Nevertheless, the available data on storage for M01 and M06 do not cover the entire period of the stored samples before the analysis (data gap).

Sufficient residue trials on barley and wheat were analysed for isoflucypram, supported by validated analytical methods and covered by storage stability were available to propose MRLs for the representative uses and animal commodities. M01 and M06 (free and conjugates) were also analysed in the field trials, but the results are not fully reliable since they were not covered by the storage stability. The MRL requests on representative uses and animal commodities were fully supported by the available data.

Hydrolysis study simulating conditions of pasteurisation, boiling/brewing/baking and sterilisation were submitted for isoflucypram, M01 and M06 shown isoflucypram and M01 are stable (98%). M06 degraded into M77 under boiling/brewing/baking up to 66% of applied radioactivity and under sterilisation up to 98%. A potential concern for genotoxicity was identified for M77 that needed further investigation (see data gap in Section 2 leading to consumer risk assessment that could not be finalised) since M06 was found in barley grain at relevant level (0.051 mg/kg). Pending the clarification on genotoxicity of M77, the residue definitions in process commodities are provisionally proposed as for the primary crops.

Processing trials in barley and wheat were submitted for isoflucypram only, but the levels of residues and the number of studies were not sufficiently to derive robust processing factors (data gap).

Livestock metabolism studies on ruminant and poultry sufficiently dosed with pyrazole and phenyl labelled isoflucypram were provided. Isoflucypram was found in all animal tissues, in milk and eggs, liver and ruminant fat. M01 and M06 were recovered at relevant amount in almost all matrices, except M01 in milk and ruminant fat. Although M07, M11 and M12 were found above 10% TRRs in poultry muscle and liver, when compared the results from poultry feeding studies M07, is not expected above 0.01 mg/kg. In ruminants, the additional relevant compounds found were M02, M19 (conjugate of M01), M20 (conjugate of M02) and M50 found in kidney (0.011 mg/kg relative amount) for which a potential concern for genotoxicity was identified and a data gap was triggered in Section 2. Even the metabolic pattern slightly differs in poultry and ruminates, considering the overall data from metabolism and the results from feeding studies, during the experts’ meeting, it was concluded to derive a general residue definition for risk assessment for poultry and ruminants as isoflucypram, M01, M19, M02, M20 and M11 expressed as isoflucypram. This residue definition might be reconsidered pending the toxicological assessment of M50. For monitoring, the residue definition was limited to isoflucypram only.

In the feeding studies on ruminants and poultry dosed with isoflucypram, the transfer of residues was investigated in all animal matrices analysing for isoflucypram, M01, M02, M06, M11, M12. In addition, M01, M19, M02 and its conjugate were analysed in ruminant kidney and liver and M06 and M37 (conjugate of M06) in poultry liver. At the estimated animal dietary burden, residues above 0.01 mg/kg were found in ruminants only, isoflucypram in fat up to 0.015 mg/kg and M01, M02 and their conjugates M19, M20 in liver for max 0.018 mg/kg. MRLs were proposed for some of animal matrices (see Appendix B).

Metabolism studies for fish were not submitted since the calculated dietary burden was below 0.1 mg/kg. Nevertheless, based on the outstanding data in primary, processing and rotational crops, the assessment in fish should be regarded as provisional.

Regarding the magnitude of residues in pollen and bee products for human consumption, four honey trials were provided analysing for isoflucypram, M01 and M06 and their conjugates. All residues were below 0.01 mg/kg. The studies were considered valid and an MRL for honey is proposed at 0.01 mg/kg. In the bee's product the same residue definitions as for primary crops are applicable.

A consumer risk assessment using the EFSA PRIMo rev.3.1 model was conducted for barley, wheat, oat, rye and animal matrices, using the toxicological reference values of isoflucypram and the derived conversion factors from monitoring to risk assessment residue definition. The chronic and acute dietary intakes were all below the ADI and ARfD for all considered European consumer groups, the highest TMDI was 3% of ADI (NL, toddler) and highest IESTI 2% of ARfD (milk cattle). The consumer risk assessment is not finalised with regard to the potential genotoxicity of metabolites M50, M66, M67 and M77.

4. Environmental fate and behaviour

Isoflucypram was discussed at the Pesticides Peer Review Experts’ Teleconference 65 in November 2021.

The rates of dissipation and degradation in the environmental matrices investigated were estimated using FOCUS (2006) kinetics guidance. In soil laboratory incubations under aerobic conditions in the dark, isoflucypram exhibited high to very high persistence, forming the major (> 10% applied radioactivity (AR)) metabolite M12 (BCS‐CN88640‐carboxylic acid, max. 10.9% AR) which exhibited moderate to very high persistence being pH dependent with higher persistence in acidic soils. Mineralisation of the [14C‐Pyrazole] and the [14C‐Phenyl] radiolabels to carbon dioxide accounted for 1.2–4.7% AR at 120–123 days and 5.2% AR after 125 days, respectively. The formation of unextractable residues (not extracted by acetonitrile/water or methanol/water) of [14C‐Pyrazole] radiolabel accounted for 3.4–10.7% AR at 120/123 days and of [14C‐Phenyl] radiolabels for 6.4% AR after 125 days. In an anaerobic soil incubation, isoflucypram exhibited very high persistence forming no novel metabolites. In a laboratory soil photolysis study, isoflucypram degraded slightly more rapidly than in the dark control forming no major metabolites.

Isoflucypram exhibited slight to low mobility in soil. For metabolite M12, a medium to very high mobility was exhibited with pH dependency of adsorption in soils clearly established, with less mobility being exhibited in acidic soils (in the data set was those with pH 5.8 or lower).

A time‐dependent sorption (TDS) study was available that gave indications that aged adsorption occurred for the parent isoflucypram. However, the available studies did not enable reliable aged adsorption parameters to be derived for four soils, so it was not possible to include this process in exposure modelling. Consequently, the exposure assessment relied on was completed using the results from guideline batch adsorption experiments using a standard first‐tier approach to adsorption parameterisation.

In satisfactory field dissipation studies carried out at six sites, three in Northern Europe (Germany, United Kingdom, Northern France) and three in Southern Europe (Southern France, Italy and Spain), isoflucypram exhibited moderate to very high persistence (spray application to the soil surface on bare soil plots in spring). Sample analyses were carried out also for metabolite M12. M12 exhibited medium to very high persistence. Field study DegT50 values were derived following normalisation to FOCUS reference conditions (20°C and pF2 soil moisture) according to the EFSA (2014a) DegT50 guidance. The field data endpoints were not combined with laboratory values to derive modelling endpoints for isoflucypram, while laboratory and field data endpoints were combined for metabolite M12. No significant correlation between field degradation rates and soil pH was assessed for isoflucypram. For metabolite M12, a pH dependence assessment on the combined laboratory and field DT50 indicated that slower degradation was observed for soil pH (CaCl2) < 6.6. The endpoints to be used for modelling for metabolite M12, including the division of data into pH‐related groups for degradation and adsorption, were agreed as covering all soil pH situations, though might be conservative for soil below pH 5.8, where higher adsorption is indicated.

In laboratory incubations in dark aerobic natural sediment water systems, isoflucypram exhibited high to very high persistence, forming the major metabolite M12 (max 5.4% AR in water and 1.3% AR in sediment after 100 days, exhibiting very high persistence). The unextractable sediment fraction (not extracted by acetonitrile, acetonitrile/water and methanol/water) was the major sink for the [14C‐Pyrazole] isoflucypram, accounting for max. 6.4% AR at study end (100 days). Mineralisation of this radiolabel accounted for 0.1% AR at the end of the study. Isoflucypram was slowly degraded in a pH 7 aqueous buffer solution under aerobic condition in the laboratory and exposure to simulated sunlight. Degradation products >10% AR were not observed; thus, photodegradation is unlikely to contribute to degradation of isoflucypram under typical light conditions in natural waters.

The necessary surface water and sediment exposure assessments (Predicted Environmental Concentrations (PEC) calculations) were carried out for isoflucypram and metabolite M12 using the FOCUS step 1 and step 2 (version 3.2 of the Steps 1–2 in FOCUS calculator) and step 3 approaches (FOCUS, 2001). 7 For isoflucypram, step 4 calculations were available for the D1 scenario for early applications in winter and spring cereals and D2 for early applications in winter cereals. The step 4 calculations have appropriately followed the FOCUS, 2007 guidance, with no‐spray drift buffer zones of up to 20 m being implemented for just these drainage scenarios (representing 58–92% drift reduction). The SWAN tool (version 4.0.1) was used to implement these mitigation measures in the simulations. However, the maximum mitigation afforded by 20 m no‐spray zones did not change the PEC as the maximum values originated from drainage events.

The necessary groundwater exposure assessments were appropriately carried out using FOCUS (European Commission, 2014) scenarios and the models PEARL 4.4.4, PELMO 5.5.3 and MACRO 5.5.4 for the active substance isoflucypram and its metabolite M12. The potential for groundwater exposure from the representative use by isoflucypram above the parametric drinking water limit of 0.1 µg/L was conducted to be low in all geoclimatic situations that are represented by all FOCUS groundwater scenarios. For metabolite M12, as a first tier, calculations were performed with a combination of endpoints selected to conservatively cover all soil pH situations.

For winter cereals, for metabolite M12 estimated 80th percentile annual average recharge concentrations moving below 1 m were > 0.1 µg/L for eight of nine scenarios and for seven of nine for early and late application timing, respectively. For spring cereals, for metabolite M12, these estimated concentrations were > 0.1 µg/L for 6/6 scenarios and for 5/6 for early and late application timing, respectively. As M12 is assessed as a relevant groundwater metabolite (see Sections 2 and 7), this has led to the identification of a critical area of concern (see Section 9.2). Should risk managers choose to introduce risk management based on restricting use to certain topsoil pH conditions, the RMS proposed and experts at the Teleconference 65 meeting agreed with a modelling approach to cover soils overlying aquifers where pH(CaCl2) was predominantly above 6.6. This was done for all representative uses and has been labelled as the tier 2 assessment. In this tier 2 assessment, PECgw calculations for metabolite M12 resulted in 80th percentile annual average recharge concentrations moving below 1 m being < 0.1 µg/L for all scenarios.

The applicant provided appropriate information to address the effect of water treatments processes on the nature of the residues that might be present in surface water and groundwater, when surface water or groundwater is abstracted for drinking water. The conclusion of this consideration was that neither isoflucypram nor its degradation product that trigger assessment (i.e. metabolite M12) would be expected to undergo any substantial transformation due to oxidation or chlorination at the disinfection stage of usual water treatment processes.

The PEC in soil, surface water, sediment and groundwater covering the representative uses assessed can be found in Appendix B. A key to the persistence and mobility class wording used, relating these words to numerical DT and Koc endpoint values can be found in Appendix C.

5. Ecotoxicology

The risk assessment was based on the following documents European Commission (2002a, 2002b,b), SETAC (2001), EFSA (2009, 2013) and EFSA PPR Panel (2013).

Pending the outcome of the data gap on the exact composition of the representative product, information whether the representative formulation was used in the ecotoxicity studies is needed (see Section ‘The active substance and the formulated product’).

The ecotoxicological profile of isoflucypram relied upon ecotoxicity studies that were not representative of the proposed technical specification for the active substance and associated impurities. This is because the proposed content of the impurity BCS‐AA10447 in the technical specification was not present in the batches used in the ecotoxicity studies leading to a data gap.

Isoflucypram was discussed at the Pesticide Peer Review Experts’ Teleconference 67 which took place in November 2021.

Acute and reproductive data were available with birds and mammals. The choice of the relevant reproductive endpoint for the assessment of wild mammals was discussed and agreed at the peer‐review meeting. 8 Based on those data, a low acute and reproductive risk was concluded for all the relevant routes of exposure (dietary, through contaminated water and secondary poisoning) for all the representative uses in cereals.

Low risk to birds and mammals when exposed to the pertinent plant metabolite M21 was concluded for all the representative uses.

Acute toxicity data with the active substance and the formulated product were available for fish and aquatic invertebrates. Chronic toxicity data with the active substance were available for fish and aquatic invertebrates, algae and macrophyte. Chronic toxicity data with the formulation were also available for algae. Endpoint for the chronic fish ELS 9 study was discussed at the experts’ meeting. Overall, all the experts agreed that the endpoint from the fish ELS study was reliable. Regarding sediment‐dwelling organisms, data were available for three different species. The study on Leptocheirus plumulosus was regarded as not sufficiently reliable for use in the risk assessment by the RMS; however, following a comment received on additional information, 10 EFSA re‐evaluated the study. Based on this re‐evaluation, EFSA considers the study as valid and reliable with restriction, since the limitation reported is not sufficient to fully reject it. Therefore, EFSA proposed to derive an endpoint from this study based on its statistical NOEC and to use it in the risk assessment for sediment‐dwelling organisms. This is not in agreement with the opinion of the RMS.

Based on the available Tier 1 data, low chronic risk to algae and aquatic macrophyte was concluded by using FOCUS Step 1 and 2 PECsw, for all the representative uses. In addition, a low chronic risk to sediment‐dwelling organisms was concluded, based on both endpoints proposed by the RMS on Chironomus and by EFSA on Leptocheirus plumulosus, for all the representative uses.

Based on FOCUS Step 3 PECsw, a low acute risk for aquatic invertebrates was concluded on winter and spring cereal (late application); a high acute risk was identified for early application. A low chronic risk to aquatic invertebrates was concluded for all representative uses.

Regarding fish, a high acute risk was identified for all representative uses at Tier 1 (FOCUS Step 3). A low chronic risk was concluded on spring cereal and winter cereal (late application). For early application on winter cereals, a high chronic risk was identified for two of nine scenarios at Tier 2 (FOCUS Step 3).

A refined acute risk assessment for aquatic invertebrate and fish based on the geometric mean approach was available (Tier 2a). Based on these data, the acute risk for aquatic invertebrates was considered low for use in winter and spring cereal, early application (FOCUS Step 3). A low acute risk to fish was also concluded for all representative uses (FOCUS Step 3) at Tier 2.

Overall considering all groups of aquatic organisms, a low risk is concluded for all scenarios except for two out of nine FOCUS scenarios (D1 and D2) in winter cereal (early application). FOCUS step 4 PEC surface water were provided; however, they did not change the outcome of the risk assessment.

One major metabolite of isoflucypram has been identified as occurring in the water and sediment phase (BCS‐CN88460‐carboxylic acid (M12)). The pertinent aquatic metabolite (M12) was tested acutely for fish and invertebrates and with algae.

Low risk was concluded for the pertinent aquatic metabolite by using FOCUS Step 1 or 2 PECsw for sediment‐dwelling organism, algae, macrophyte, acute and chronic aquatic invertebrate and acute fish. Low chronic risk to fish was concluded for the pertinent aquatic metabolite by using FOCUS Step 3 PECsw.

For honeybees, acute toxicity data were available for the active substance and the formulation; chronic larvae data were available for the active substance and adult chronic data were available for one formulation (BCS‐CN88460 SC 200 (200 G/L), which is not the representative one. No comparison of the two formulations was done nor was a justification provided as to why a study with this formulation can be considered as representative of the active substance. Based on the available data, the active substance seems to be more acutely toxic when formulated, especially by contact. Four semi‐field studies were available for honey bees with the formulation. The reliability of the chronic larvae study and the four semi‐field studies was discussed during the experts’ meeting. 11 Overall, it was agreed that the chronic larvae study was reliable and that three of the semi‐field studies were reliable. The last semi‐field study was not sufficiently reliable for deriving bee endpoints, but was considered reliable to derive residue values under semi‐field conditions.

Acute toxicity studies were also available for the active substance on bumble bees.

The risk assessment was carried on based on European Commission (2002a, 2002b) and EFSA (2013) guidances. Based on the available data, a low acute risk for adult and larva honeybees and bumblebees at the screening step for both the active substance and the formulation was concluded for all the representative uses. The chronic risk assessment with ‘BCS‐CN88460 SC 200 (200 G/L)' indicated a low chronic risk to honey bees. However, without proper justification, EFSA does not consider that an endpoint with a formulation can be used to assess the chronic risk from the active substance. Furthermore, the available semi‐field studies cannot be considered to adequately address the chronic risk. Consequently, EFSA considers that the chronic risk assessment for adult bees could not be finalised and a chronic toxicity study for adult honeybees with the active substance is needed. This is not in agreement with the RMS, which was of the opinion that the chronic risk assessment with ‘BCS‐CN88460 SC 200 (200 G/L)' together with the available semi‐field studies allowed to conclude on a low chronic risk to adults bees.

There was no Tier 1 assessment of sublethal (e.g. hypopharygeal gland (HPG)) or accumulative effect. This was discussed during the experts’ meeting. 12 The experts agreed that the three reliable higher tier studies can be used to cover those effects. A low acute risk to honey bees for the 11 relevant metabolites identified (i.e. ≥ 0.01 mg/kg in primary crop metabolism studies) was concluded based on the available assessments. A low acute risk to honeybees and honeybee larvae was concluded for exposure to contaminated water and guttation. A chronic risk assessment could not be performed owing to the lack of chronic laboratory toxicity study.

No data were submitted to perform a risk assessment for solitary bees.

Tier 1 laboratory studies on non‐target arthropods (NTAs) other than bees were provided with the standard species, the predatory mite Typhlodromus pyri and the parasitic wasp Aphidius rhopalosiphi. In addition, Tier 2 extended laboratory studies were available for the standard species as well as for two additional species, Chrysoperla carnea and Coccinella septempunctata. Finally, an aged residue laboratory study was submitted for A. rhopalosiphi.

Based on the available information and risk assessment, a high in‐field risk was identified for the two standard species at Tier 1. At Tier 2, a high risk was identified for A. rhopalosiphi and T. pyri, based on extended laboratory studies, whilst a low risk was identified for the two additional species. Since A. rhopalosiphi was the most sensitive species in the laboratory studies, the refined Tier 2 risk assessment based on the aged residue study was considered to cover T. pyri. From the refined Tier 2 risk assessment, a low risk was concluded for the non‐target arthropods in the in‐field area from the intended uses of ‘Isoflucypram EC 50’.

In addition, a low off‐field risk for NTAs was concluded for the representative uses at Tier 1.

Chronic toxicity studies were conducted with earthworms and soil meso‐ and macrofauna (other than earthworms) for the active substance and the representative formulation. Furthermore, a chronic toxicity study was provided with the pertinent soil metabolite (M12) of isoflucypram.

Based on the available data and risk assessment, a low risk to earthworms and soil meso‐ and macrofauna (other than earthworms) was concluded for isoflucypram and the metabolite for the representative uses.

Studies on the effects of isoflucypram, the representative formulation and the metabolite on soil micro‐organisms were available. Based on the available data, the risk to soil microorganisms from exposure to isoflucypram, the representative formulation and the metabolite M12 was considered low.

Non‐target terrestrial plant (NTTPs) toxicity studies with the representative formulation were submitted for several species. Based on the available data and risk assessment, a low risk to NTTP was concluded for the representative uses.

A study was available with the active substance to address the impact of isoflucypram on the biological methods for sewage treatment, and based on these data, a low risk was concluded.

6. Endocrine disruption properties

With regard to the assessment of the endocrine disruption potential of isoflucypram for humans according to the ECHA/EFSA guidance (2018), the number and type of effects induced, and the magnitude and pattern of responses observed across studies were considered to determine whether isoflucypram interacts with the oestrogen, androgen and steroidogenesis (EAS) and thyroid (T)‐mediated pathways. Additionally, the conditions under which the effects occur were examined, in particular, whether or not endocrine‐related responses occurred at dose(s) that also resulted in overt toxicity. This assessment therefore provides a weight‐of‐evidence analysis of the potential interaction of isoflucypram with the EAS‐ and T‐signalling pathways using the available evidence in the data set.

The data set for the T‐modality was considered as sufficiently investigated with evidence of thyroid‐mediated adversity observed in one species (rat). A liver‐mediated mode of action (MoA) was postulated (CAR/PXR nuclear receptor activation, induction in Phase I and Phase II liver enzymes, increase in thyroid hormones clearance and decrease in the circulating level of thyroid hormones). However, additional molecular initiating events leading to alternative mode of actions could not be excluded based on the available evidence. In addition, there is also uncertainty on the impact of the observed changes in the thyroid on the most sensitive population of concern for thyroid hormone system toxicity (dams, fetuses and newborns).

Because of lack of data in the most sensitive population of concern, the ED assessment for the T‐modality for humans according to point 3.6.5 of Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, as amended by Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/605, cannot be concluded, leading to an issue not finalised (see Section 9.1).

To complete the data package, a study in line with the US EPA Comparative Thyroid Assessment Guidance for Thyroid Assays in Pregnant Animals, Foetuses and Postnatal Animals (US EPA, Office of Pesticide Programs, Health Effects Division, Washington (DC), 2005) should be conducted. Such study should be conducted following the below recommendations:

-

–

the doses should be high enough to allow a proper exploration of thyroid toxicity;

-

–

a positive control should be included;

-

–

iodine content in the diet should be controlled (should not be exceeding 5 µg/kg food, which is the rodent daily need);

-

–

the methodology for sampling and the analytical method to evaluate thyroid hormones (T4 and T3) (THs) and thyroid‐stimulating hormone (thyrotropin) (TSH) should be provided;

-

–

laboratory documentation of the method validation for the assessment of THs and THS with inclusion of the limit of determination for fetuses and pups should be provided.

Alternatively, a developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) study in line with the OECD TG 426 including measurements of thyroid hormones and thyroid pathology can be conducted.

The data set for the EAS‐modalities was considered as sufficiently investigated with no evidence of adversity (scenario 1a). Therefore, for the EAS‐modalities, the ED criteria for humans according to point 3.6.5 of Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, as amended by Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/605, were considered not met.

The endocrine‐disrupting properties of Isoflucypram for non‐target organisms were discussed in the Peer Review Experts’ Teleconference. 13 In line with the conclusion for humans, further data (a study in line with the USEPA Thyroid assessment assay) are needed to conclude on the ED properties of isoflucypram for wild mammals through the T modality. For the EAS‐modalities, the conclusion drawn for humans also apply to wild mammals (criteria not met).

For non‐target organisms other than mammals, in the revised DAR two Xenopus Eleutheroembryo Thyroid Assay (XETA), a modified AMA (extended to 43 days), an FSTRA, a Rapid Androgen Disruption Adverse‐outcome Reported assay (RADAR) and a Rapid Estrogen ACTivity In Vivo assay (REACTIV) assays were reported. Considering the information available in the DAR and the uncertainty in the available data set (i.e. one XETA positive, some effect seen on hind limb length and histopathology in the modified Amphibian Metamorphosis Assay (AMA)) experts agreed the followings:

-

–

For the T‐modality, the available evidence did not allow to draw a robust conclusion based on uncertainety in the available dataset; therefore as a first step and in line with the ECHA/EFSA Guidance an MoA analysis should be postulated. Once postulated, the need for generating further information (i.e. LAGDA) allowing to reach a conclusion should be considered.

-

–

For the EAS modalities, no effects were observed in the available data set, and therefore, criteria are considered unlikely to be met.

It was, however, noted that all the available studies were either submitted after the stop of the clock or only interim results were available, and therefore, they were not eligible to be considered in the assessment (data gap for full study reports). Nevertheless, the available assessment was considered and discussed.

Based on the above considerations, Isoflucypram is not considered to meet the criteria for endocrine disruption for the EAS modalities for humans and is considered unlikely to meet the criteria for endocrine disruption for the EAS modalities for the non‐target organisms. The assessment of the endocrine‐disrupting properties of isoflucypram for humans and non‐target organisms according to point 3.6.5 and 3.8.2 of Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, as amended by Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/605 could not be finalised.

7. Overview of the risk assessment of compounds listed in residue definitions triggering assessment of effects data for the environmental compartments ( Tables 1, 2, 3 – 4 )

Table 1.

Soil

| Compound (name and/or code) | Ecotoxicology |

|---|---|

| Isoflucypram | Risk to soil organisms was assessed as low |

| M12 (BCS‐CN88640‐carboxylic acid) | Risk to soil organisms was assessed as low |

Table 2.

Groundwater (a)

|

Compound (name and/or code) |

> 0.1 μg/L at 1 m depth for the representative uses (b) Step 2 |

Biological (pesticidal) activity/relevance Step 3a. |

Hazard identified Steps 3b. and 3c. |

Consumer RA triggered Steps 4 and 5 |

Human health relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflucypram | No | Yes | – | – |

Yes |

|

M12 (BCS‐CN88640‐carboxylic acid) |

Yes (Tier 1) Winter cereals (early application, DT50 116.6 days): 8/9 FOCUS scenarios (0.198–0.375 μg/L) Winter cereals (late application, DT50 116.6 days): 7/9 FOCUS scenarios (0.113–0.183 μg/L) Spring cereals (early application, DT50 116.6 days): 6/6 FOCUS scenarios (0.178–0.425 μg/L) |

No |

Yes Unlikely to be genotoxic, data are not available to demonstrate that M12 did not share the same reproductive toxicity potential as isoflucypram. |

No |

Yes |

|

Spring cereals (late application, DT50 116.6 days): 5/6 FOCUS scenarios (0.103–0.205 μg/L) No (Tier 2) for all representative uses in soil with pH > 6.6 and DT50 37.8 d |

Assessment according to European Commission guidance of the relevance of groundwater metabolites (2003).

FOCUS scenarios or relevant lysimeter.

Table 3.

Surface water and sediment

| Compound (name and/or code) | Ecotoxicology |

|---|---|

| Isoflucypram |

Risk to sediment‐dwelling organisms was assessed as low Risk to aquatic organisms was assessed as low for the majority of the representative FOCUS surface water scenarios, except for 2 out of 9 scenarios (D1 and D2, high chronic risk) |

| M12 (BCS‐CN88640‐carboxylic acid) | Risk to aquatic organisms and sediment‐dwelling organisms was assessed as low |

Table 4.

Air

|

Compound (name and/or code) |

Toxicology |

|---|---|

| Isoflucypram | Rat LC50 inhalation: 2.5 mg/L air/4 h (aerosol; nose only) |

8. Particular conditions proposed to be taken into account by risk managers

Risk mitigation measures (RMMs) identified following consideration of Member State (MS) and/or applicant’s proposal(s) during the peer review, if any, are presented in this section. These measures applicable for human health and/or the environment leading to a reduction of exposure levels of operators, workers, bystanders/residents, environmental compartments and/or non‐target organisms for the representative uses are listed below. The list may also cover any RMMs as appropriate, leading to an acceptable level of risks for the respective non‐target organisms.

It is noted that final decisions on the need of RMMs to ensure the safe use of the plant protection product containing the concerned active substance will be taken by risk managers during the decision‐making phase. Consideration of the validity and appropriateness of the RMMs remains the responsibility of MSs at product authorisation, taking into account their specific agricultural, plant health and environmental conditions at national level.

Table 5 Risk mitigation measures proposed for the representative uses assessed

| Representative use | Cereals |

|---|---|

| Foliar spray | |

| Operator risk | |

| Worker exposure | |

| Bystander/resident exposure | Buffer zone 2–3 m |

| Risk to aquatic organisms |

9. Concerns and related data gaps

9.1. Issues that could not be finalised

An issue is listed as ‘could not be finalised’ if there is not enough information available to perform an assessment, even at the lowest tier level, for one or more of the representative uses in line with the uniform principles in accordance with Article 29(6) of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 and as set out in Commission Regulation (EU) No 546/2011 14 and if the issue is of such importance that it could, when finalised, become a concern (which would also be listed as a critical area of concern if it is of relevance to all representative uses).

An issue is also listed as ‘could not be finalised’ if the available information is considered insufficient to conclude on whether the active substance can be expected to meet the approval criteria provided for in Article 4 of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009.

The following issues or assessments that could not be finalised have been identified, together with the reasons including the associated data gaps where relevant, which are reported directly under the specific issue to which they are related:

-

1

The assessment of the endocrine disruption properties of isoflucypram for humans for the T‐modality and for non‐target for EATS‐modalities could not be finalised. Further assessment is needed on the impact of the observed changes in the thyroid on the most sensitive population of concern for thyroid toxicity (dams, fetuses and newborns) (see Section 6).

-

a

A study in line with the US EPA Comparative Thyroid Assessment Guidance for Thyroid Assays in Pregnant Animals, Foetuses and Postnatal Animals (US EPA, Office of Pesticide Programs, Health Effects Division, Washington (DC). 12 pp. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015‐06/documents/thyroid_guidance_assay.pdf) should be conducted. Such study should be conducted following the below recommendations:

-

a

The doses should be high enough to allow a proper exploration of thyroid toxicity;

A positive control should be included;

Iodine content in the diet should not be exceeding 5 µg/kg food (rodent daily need);

The methodology for sampling and the analytical method to evaluate THs and TSH should be provided;

Laboratory documentation of the method validation for the assessment of THs and THS with inclusion of the limit of determination for foetuses and pups should be provided.

Alternatively, a DNT study in line with the OECD TG 426 including measurements of thyroid hormones and thyroid pathology can be conducted (the applicant should complete the data package to support a conclusion on the absence of T‐mediated adversity/endocrine activity within an estimated time period of 18 months).

-

b

For non‐target organisms other than mammals, for the T‐modality, as a first step an MoA should be postulated. Once postulated, the need for generating further information (i.e. LAGDA) allowing to reach a conclusion should be considered (for the first step, i.e. MoA analysis, the applicant should complete the data package to support a conclusion on the absence of EATS‐mediated adversity/endocrine activity within an estimated time period 2 months. If following the first step, additional data are triggered, i.e. LAGDA according to OECD 241, an additional estimated time period of 27 months would be needed.

-

c

All relevant studies considered in the context of the ED assessment, i.e. XETA, Modified AMA, RADAR, REACTIV, FSTRA should be submitted (the submission should be completed by the timelines indicated in point b).

-

2

The consumer dietary risk assessment could not be finalised since the risk assessment residue definition in livestock, rotational and processed commodities is provisional (see Section 3):

Pending genotoxicity data for the metabolites M50, M66, M67 and M77 (relevant for all the representative uses; see Section 2).

Storage stability during storage data for M01 and M06 relevant metabolites for plant risk assessment residue definition was submitted only for 6 months while the samples were stored up to 18 months (barley) and 29 months (wheat) (relevant for all the representative uses; see Section 3).

-

3

The chronic risk assessment for adult bees could not be finalised (see Section 5).

A chronic toxicity study for adult honeybees, with the active substance is needed (relevant for all the representative uses; see Section 5).

-

2

9.2. Critical areas of concern

An issue is listed as a critical area of concern if there is enough information available to perform an assessment for the representative uses in line with the uniform principles in accordance with Article 29(6) of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 and as set out in Commission Regulation (EU) No 546/2011, and if this assessment does not permit the conclusion that, for at least one of the representative uses, it may be expected that a plant protection product containing the active substance will not have any harmful effect on human or animal health or on groundwater, or any unacceptable influence on the environment.

An issue is also listed as a critical area of concern if the assessment at a higher tier level could not be finalised due to lack of information, and if the assessment performed at the lower tier level does not permit the conclusion that, for at least one of the representative uses, it may be expected that a plant protection product containing the active substance will not have any harmful effect on human or animal health or on groundwater, or any unacceptable influence on the environment.

An issue is also listed as a critical area of concern if, in the light of current scientific and technical knowledge using guidance documents available at the time of application, the active substance is not expected to meet the approval criteria provided for in Article 4 of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009.

The following critical areas of concern are identified, together with any associated data gaps, where relevant, which are reported directly under the specific critical area of concern to which they are related:

-

4

The toxicological profile of isoflucypram relied upon toxicity studies that were not representative of the proposed technical specification for the active substance and associated impurities. This is because the proposed content of the relevant impurity BCS‐AA10447 in the technical specification is not supported from the toxicology point of view (see Section 2).

For the toxicologically relevant impurity BCS‐AA10447, a maximum acceptable level in the technical specification has not been determined.

-

5

When groundwater aquifers are overlaid by soils which have pH(CaCl2) that are predominantly below 6.6, there is a high potential predicted for groundwater exposure by the groundwater relevant metabolite M12 at a majority (8/9) of the FOCUS groundwater scenarios for the representative uses on cereals when autumn sown and all FOCUS scenarios when spring sown. M12 has to be concluded as relevant whilst data are not available to demonstrate it does not share the same reproductive toxicity potential as isoflucypram (see Sections 2, 4 and 7).

9.3. Overview of the concerns identified for each representative use considered ( Table 6 )

Table 6.

Overview of concerns reflecting the issues not finalised, critical areas of concerns and the risks identified that may be applicable for some but not for all uses or risk assessment scenarios

| Representative use | Wheat | Rye | Triticale | Barley | Oats | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operator risk | Risk identified | |||||

| Assessment not finalised | ||||||

| Worker risk | Risk identified | |||||

| Assessment not finalised | ||||||

| Resident/bystander risk | Risk identified | |||||

| Assessment not finalised | ||||||

| Consumer risk | Risk identified | |||||

| Assessment not finalised | X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | X2 | |

| Risk to wild non‐target terrestrial vertebrates | Risk identified | |||||

| Assessment not finalised | ||||||

| Risk to wild non‐target terrestrial organisms other than vertebrates | Risk identified | |||||

| Assessment not finalised | X3(c) | X3(c) | X3(c) | X3(c) | X3(c) | |

| Risk to aquatic organisms | Risk identified |

X (d) 2/9 scenarios |

X (d) 2/9 scenarios |

X (d) 2/9 scenarios |

X (d) 2/9 scenarios |

X (d) 2/9 scenarios |

| Assessment not finalised | ||||||

| Groundwater exposure to active substance | Legal parametric value breached | |||||

| Assessment not finalised | ||||||

| Groundwater exposure to metabolites | Legal parametric value breached | X5(a) | X5(a) | X5(a) | X5(a) | X5(a) |

| Parametric value of 10 µg/L (b) breached | ||||||

| Assessment not finalised | ||||||

The superscript numbers relate to the numbered points indicated in Sections 9.1 and 9.2. Where there is no superscript number, see Sections 2–7 for further information.

When groundwater aquifers are overlaid by soils which have pH(CaCl2) that are predominantly below 6.6 8/9 FOCUS scenarios autumn sown, all scenarios spring sown. Parametric value not breached when overlying soils have pH(CaCl2) above 6.6.

Value for non‐relevant metabolites prescribed in SANCO/221/2000‐rev. 10 final, European Commission, 2003.

Chronic risk assessment to adult bees could not be finalised.

High chronic risk to aquatic organisms in winter cereal, early application. Risk to aquatic organisms for spring cereal was low in all scenarios.

(If a particular condition proposed to be taken into account to manage an identified risk, as listed in Section 8, has been evaluated as being effective, then ‘risk identified’ is not indicated in Table 6).

In addition to the issues indicated in Table 6 below, the technical material specification proposed was not comparable to the material used in the testing that was used to derive the (eco)toxicological reference values.

In addition to the issues indicated below, the assessment of the endocrine‐disrupting properties of isoflucypram for humans and non‐target organisms according to the scientific criteria for the determination of endocrine‐disrupting properties as set out in points 3.6.5 and 3.8.2 of Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, as amended by Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/605, could not be finalised.

10. List of other outstanding issues

Remaining data gaps not leading to critical areas of concern or issues not finalised but considered necessary to comply with the data requirements, and which are relevant for some or all of the representative uses assessed at EU level. Although not critical, these data gaps may lead to uncertainties in the assessment and are considered relevant.

These data gaps refer only to the representative uses assessed and are listed in the order of the sections:

Information on the exact composition of the representative formulation (which of all alternative co‐formulants was used) is required. In addition, information whether the representative formulation was used in the studies for data generation on physical chemical and technical properties, efficacy and analytical methods of the product as well as all other studies used for risk assessment and performed with a formulation (e.g. (eco)toxicological studies) is needed. If alternative formulations were used all information needed for performance of equivalence check between the representative formulation and the used alternative formulation(s) should be provided (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 1).

Spectral data for the relevant impurities BCS‐CR73065 and BCS‐AA10447 (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 1)

The content of the relevant impurities BCS‐CR73065 and BCS‐AA10447 before and after storage of the plant protection product for 2 years at ambient temperature (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 1)

Methods for analysis of the relevant impurities (BCS‐CR73065 and BCS‐AA10447) in the representative formulation (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 1)

Method for determination of metabolite M12 in water (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 1)

Method for monitoring of metabolite M58 in body fluids (plasma) (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 1)

A new comparative in vitro metabolism study in human and animal hepatocytes (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 2).

In vitro testing of isoflucypram and major human metabolites for their potential to inhibit SDH (complex II) and other complexes which are involved in the electron transport chain (ETC) (relevant for all representative uses evaluated; see Section 2).

Processing trials were not submitted and they were triggered (relevant for the uses in wheat and barley, see Section 3).

The toxicological profile of isoflucypram relied upon ecotoxicity studies that were not representative of the proposed technical specification for the active substance and associated impurities. This is because the proposed content of the relevant impurity BCS‐AA10447 in the technical specification is not supported from the toxicology point of view (see Section 5).

Abbreviations

- AMA

Amphibian Metamorphosis Assay

- ADI

acceptable daily intake

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion

- AAOEL

acute acceptable operator exposure level

- AOEL

acceptable operator exposure level

- bw

body weight

- DAR

draft assessment report

- DNT

developmental neurotoxicity

- DT50

period required for 50% dissipation (define method of estimation)

- DT90

period required for 90% dissipation (define method of estimation)

- EAS

oestrogen, androgen and steroidogenesis modalities

- EC50

effective concentration

- ECHA

European Chemicals Agency

- EEC

European Economic Community

- ELS

Early Life Stage test

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- FOCUS

Forum for the Co‐ordination of Pesticide Fate Models and their Use

- FSTRA

Fish Short‐Term Reproduction Assay

- HPLC‐MS

high‐pressure liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- HPG

hypopharygeal glands

- IESTI

international estimated short‐term intake

- ISO

International Organization for Standardization

- IUPAC

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

- iv

Intravenous

- JMPR

Joint Meeting of the FAO Panel of Experts on Pesticide Residues in Food and the Environment and the WHO Expert Group on Pesticide Residues (Joint Meeting on Pesticide Residues)

- Kdoc

organic carbon linear adsorption coefficient

- KFoc

Freundlich organic carbon adsorption coefficient

- LAGDA

Larval Amphibian Growth and Development Test

- LC50

lethal concentration, median

- LOQ

limit of quantification

- mm

millimetre (also used for mean measured concentrations)

- MRL

maximum residue level

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MTD

maximum tolerated dose

- NOAEL