Abstract

Carbapenem-resistant bacteria have quickly become a worldwide concern in nosocomial infections. Of the seven known carbapenemases, four have been shown to be particularly problematic: KPC, NDM, IMP, and VIM. To date, many local and species- or carbapenemase-specific epidemiological studies have been performed, which often focus on the organism itself. This report attempts to perform an inclusive (encompass both species and carbapenemase) epidemiologic study using publicly available plasmid sequences from NCBI. In this report, the gene content of these various plasmids has been characterized, replicon types of the plasmids identified, and the global spread and species promiscuity of the plasmids analyzed. Additionally, support to several groups targeting plasmid maintenance and transfer mechanisms to slow the spread of resistance plasmids is given.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, carbapenemase, Enterobacteriaceae, plasmid, global distribution, résistance aux antimicrobiens, carbapénémase, Enterobacteriaceae, plasmide, distribution mondiale

Résumé:

Les bactéries résistantes aux carbapénèmes sont rapidement devenues un problème mondial en matière d’infections nosocomiales. Des sept carbapénémases connues, quatre se sont montrées particulièrement problématiques : KPC, NDM, IMP et VIM. À ce jour, plusieurs études épidémiologiques à portée locale ou spécifiques d’une espèce ou d’une carbapénémase ont été réalisées et portaient généralement sur l’organisme lui-même. Ce travail cherchait à réaliser une étude épidémiologique englobante (incluant à la fois les espèces et les carbapénémases) à partir des données publiques sur les séquences plasmidiques disponibles dans NCBI. Dans ce travail, les auteurs rapportent le contenu en gènes des différents plasmides qui ont été caractérisés, les types de réplicons chez les plasmides identifiés ainsi que la propagation mondiale et la promiscuité des espèces pour les plasmides analysés. De plus, un appui est fourni aux nombreux groupes qui travaillent sur le maintien des plasmides et leurs mécanismes de transfert afin de ralentir la propagation des plasmides conférant la résistance. [Traduit par la Rédaction]

Introduction

Nosocomial infections have quickly become a significant cause of mortality. In 2002, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that the national mortality rate due to hospital-acquired infections was 5.8% (Klevens et al. 2007). In 2011, that rate increased to 10.4% (Magill et al. 2014). While these same reports show that the chance of acquiring an infection at the hospital has decreased, the infections are becoming strikingly more lethal.

One significant reason for this increase in mortality is the acquisition of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations (Read and Woods 2014). To mitigate the havoc wrought by β-lactamases on the efficacy of antimicrobials, multiple β-lactam derivatives have been pressed into service. One of these derivate classes, the carbapenems, is used as a last resort for treating extended spectrum β-lactamase infections. Recently, resistance to this class has occurred as well. Antibacterial resistance is often conferred to these organisms through extra-chromosomal segments of DNA called plasmids (Read and Woods 2014). Plasmids often carry the molecular machinery to replicate themselves and allow for the transfer of the plasmid between different bacterial strains, and even between many gram-negative bacteria (Logan and Weinstein 2017). Additionally, many carbapenemase-carrying plasmids are large; therefore, they often carry a toxin/anti-toxin plasmid addiction system (Tsang 2017) or plasmid partitioning system to prevent the bacterium from losing the plasmid. Furthermore, evidence has been shown for local and global transmission of carbapenemase genes among several bacterial species (Logan and Weinstein 2017; Stoesser et al. 2017), leading to a global crisis in the declination of antibiotic therapy efficacy.

Carbapenemases

Currently there are about nine diverse types of carbapenemases falling into Ambler classes A, B, and D (Yong et al. 2009; Overturf 2010). Each of those nine types have several allele variations. We will focus on four clinically relevant types found in Enterobacteriaceae, the class A serine-mediated Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (blaKPC) and three class B metallo-β-lactamases (blaMBL): the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) (blaNDM), the Verona integron-encoded MBL (blaVIM), and the Imipenem-resistant MBL (blaIMP), and highlight their pertinent characteristics.

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase

First identified in 2001 (Yigit et al. 2001), blaKPC was not the first carbapenemase, as several MBLs that could hydrolyze carbapenem had already been identified in Japan in 1994 (Paterson and Bonomo 2005). This initial variant (now referred to as KPC-2) provided resistance to numerous penicillins, all the cephalosporins, and aztreonam, and was also resistant to the β-lactamase inhibitors clavulanic acid and tazobactam (Yigit et al. 2001). A recent review indicates that there are currently 12 reported variants of the KPC enzyme (Sotgiu et al. 2018). As of 27 February 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that blaKPC-positive infections have been reported from all 50 states and the District of Columbia (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention n.d.; https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cre/trackingcre.html). KPC enzymes have also been reported from many other nations and in numerous gram-negative species, including Acinetobacter baumanii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and nearly all the Enterobacteriaceae (Arnold et al. 2011; Perez and Van Duin 2013; Codjoe and Donkor 2018). The ease of blaKPC gene transfer has been augmented by the Tn4401 transposon that flanks the KPC-1 gene (Arnold et al. 2011).

New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase

Originally isolated from India in 2008, there are currently more than 10 reported variants of blaNDM (Bedenić et al. 2014). They are present in 34 states (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention n.d.; https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cre/trackingcre.html) and multiple countries including the United Kingdom, Pakistan, India, Sweden, and others (Perez and Van Duin 2013). This type of carbapenemase has shown greater enzymatic activity than the blaVIM and bla types for the penicillins, cephalosporins, and a few of the carbapenems (Yong et al. 2009). blaNDM has shown a greater potential for spread than blaKPC, as it has rapidly appeared across the world in the last 10 years.

Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase

blaVIM has 14 reported variants with amino acid content varying up to 10% (Bedenić et al. 2014). blaVIM originated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the Mediterranean in 1997, but quickly spread into Enterobacteriaceae and proceeded to spread globally. Reports indicate that blaVIM can hydrolyze all β-lactams except monobactams, and remains susceptible to inhibitors (Marsik and Nambiar 2011). Like the other carbapenemases, plasmids are the primary mechanism for horizontal gene transfer of this carbapenemase.

Imipenem-resistant metallo-β-lactamase

blaIMP shares many of the same characteristics as blaVIM, but the amino acid content between the two diverges by 70% (Bedenić et al. 2014). blaIMP also represents the most diverse type of carbapenemase with 18 variants reported (Bedenić et al. 2014). Isolated in 1991 in Japan, it is the earliest carbapenemase of the four, and is resistant to the inhibitor clavulanic acid (Watanabe et al. 1991).

While there are other reports that characterize carbapenemase plasmids, these generally describe a single carbapenemase within a species (see Johnson and Woodford 2013; Sheppard et al. 2016; Stoesser et al. 2017; Piazza et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2019; Mansour et al. 2019; Mukherjee et al. 2019). This report is the first large-scale attempt to characterize the diversity and promiscuity of plasmids carrying one of four carbapenemase families across multiple bacterial species. However, the impact of this study is limited due to the regional bias introduced by national surveillance and sequencing programs. Additionally, blaOXA-48 carbapenemase was excluded due to its sequence similarities to other OXA-type β-lactamases and because of its reported decreased efficiency in hydrolytic activity towards carbapenems (Poirel et al. 2012). We identified these carbapenemase-carrying plasmids from seven clinically-relevant gram-negative bacteria (Enterobacter aerogenes (also Klebsiella aerogenes (Tindall et al. 2017)), Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Providencia stuartii, and Serratia marcescens).

Materials and methods

A detailed description and the full dataset can be found in the supplementary data, File S11.

Sequence acquisition

In total, 532 complete plasmid sequences were obtained from NCBI nucleotide database by a discontiguous megablast nucleotide search (Altschul et al. 1990) of four representative carbapenemase genes (blaIMP-4, blaKPC-2, blaNDM-1, blaVIM-1) to allow for variations within the carbapenemase family. We employed the same Entrez strategy used by Orlek et al. (2017) in the BLAST search to filter for complete plasmids:

“biomol_genomic[PROP] AND plasmid[filter] NOT complete cds[Title] NOT gene[Title] NOT genes[Title] NOT contig[Title] NOT scaffold[Title] NOT whole genome map[Title] NOT partial sequence[Title] NOT partial plasmid[Title] NOT locus[Title] NOT region[Title] NOT fragment[Title] NOT integron[Title] NOT transposon[Title] NOT insertion sequence[Title] NOT insertion element[Title] NOT phage[Title] NOT operon[Title]”

This BLAST search was done separately for the seven organisms of interest: E. aerogenes, E. cloacae, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, P. stuartii, and S. marcescens. GenBank files were downloaded for each BLAST alignment that scored >80% identity and query coverage. These sequences were retrieved on 5 March 2018.

Plasmid gene composition

A list of key terms was derived by a random survey of 10% of the acquired GenBank files, with cross reference to QuickGO, the European Bioinformatics Institute’s Gene Ontology reference database to classify gene products into one of the following categories: antimicrobial resistance, with β-lactamases as a subset; plasmid transfer genes; toxin/antitoxin systems; DNA maintenance, modifying, and repair proteins; mobile genetic elements; hypothetical genes; and other.

Incompatibility group/replicon typing and plasmid characterization

Plasmid incompatibility groups were determined by nucleotide BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990; Camacho et al. 2009) against a local download of the PlasmidFinder v1.3 Enterobacteriaceae database containing the origin sequences for numerous replicon types (Carattoli et al. 2014) downloaded on 1 March 2018. The incompatibility groups were assigned when matches met the following criteria: ≥80% identity, ≥60% subject coverage, and within 1% of the percent identity of the highest match. Accordingly, more than one incompatibility group could be reported for any given plasmid. Further characterization was accomplished as follows: extracting the CDS regions for each plasmid, searching these CDS regions for key terms using regular expressions, and combining the results for plasmid groups of interest (e.g., those that belong to Enterobacteriaceae, or those that carry blaKPC). Additionally, associated metadata were extracted for plasmids that identified a country of origin to elucidate the global prevalence of these plasmids.

Nondiscrete plasmid groups

Ultimately, the plasmid sequences were BLASTed against each other to identify any duplicate entries, and the following metadata was identified for any match exceeding 98% coverage and identity match: the organism from which the plasmid was extracted, the country of origin, and the collection date of the plasmid. The tree was constructed using a custom distance metric and Python (https://python.org) code from the CAM package (Miller et al. 2019). The custom distance metric is described in detail in the supplementary data (File S11). Briefly, it is the sum of the bases from the query and subject included in the alignment divided by the sum of the length of the query and subject sequences. The image of the tree was generated using FigTree v1.4.4 (https://github.com/rambaut/figtree).

This characterization of each plasmid and of groups of plasmids was accomplished using custom scripts, made freely available at https://github.com/ridgelab/plasmidCharacterization and in the supplementary data (File S11).

Statistical analyses

Since plasmid length distributions are not normal (left-skewed, Fig. S11), all statistical analyses were performed with the Mann–Whitney U-test or the Kruskal–Wallis ranked ANOVA where appropriate, for nonparametric distributions. To be conservative due to our large sample size, statistical significance was determined when p < 0.0001.

Results

Plasmid gene composition

Due to the inherent inconsistencies of GenBank record annotations, our search method required discarding 86/532 accessions, leaving a total of 446 accessions in this analysis. The criteria for keeping an accession in the analysis was if at least one, and no more than six, carbapenemase genes were identified on the plasmid (full dataset available in Table S11). To account for poor assembly and annotation due to short-read sequencing technologies, we identified from the metadata which technologies were used. Of the 86 GenBank files discarded, 27 used short-read technologies and 46 used long-read technologies. Of the GenBank files retained, 271 GenBank files noted the sequencing technology used, of which 48 used more than one with 40 of these using a short-read/long-read strategy. Overall there was an even distribution of short- and long-read sequencing technologies (198 short- and 121 long-read technologies). Of those 446 plasmids, 198 carry blaKPC, 168 carry blaNDM, 49 carry blaIMP, and 31 carry blaVIM. When identifying species of origin, 7 plasmids belong to E. aerogenes, 33 to E. cloacae, 142 to E. coli, 235 to K. pneumoniae, 18 to P. aeruginosa, 3 to P. stuartii, and 8 to S. marcescens. The mean size of all carbapenemase-carrying plasmids was 104 222 bp, with a median length of 87 663 bp. The largest plasmid was 500 840 bp and the smallest 1635 bp. The average percent gene content of all plasmids was as follows: antimicrobial-resistance genes, 8.0%; plasmid transfer genes, 15.8%; DNA modification genes, 14.7%; mobile genetic elements, 9.3%; hypothetical genes, 33.2%; other/metabolic genes, 18.9%. The plasmids carried, on average, two β-lactamases, with 22.6% of the plasmids carrying three or more, and the most β-lactamases on a single plasmid was six. The carbapenemase copy number of these plasmids ranged from one to three, with 97.98% of the plasmids harboring only one copy. Of those that harbored more than one carbapenemase gene, they all belonged to the same type.

Plasmid incompatibility group/replicon typing

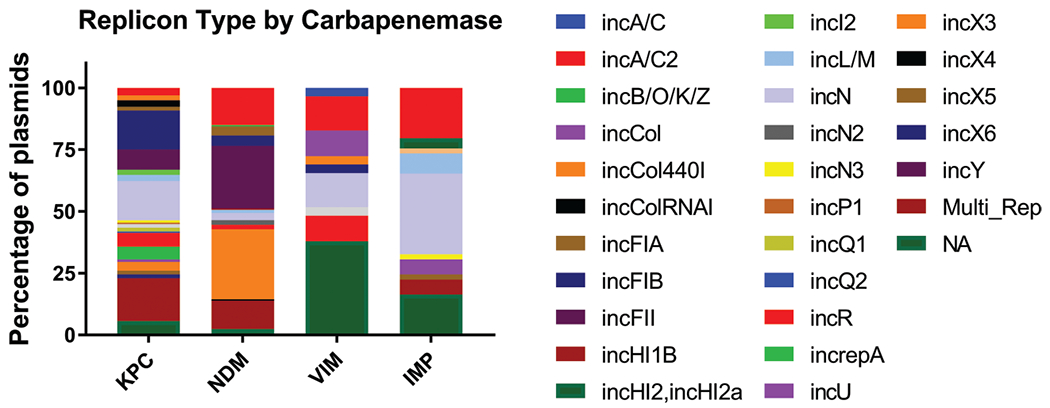

No incompatibility group presented itself as the most abundant; however, the following six groups constitute 70.4% of the plasmids: IncA/C2 (45/446, 10.1%), IncFIB (39/446, 8.7%), IncFII (58/446, 13%), IncN (56/446, 12.6%), IncX3 (54/446, 12.1%), and multi-replicon plasmids (62/446, 13.9%) (see Table S21). Notably, 7.62% (34/446) of the plasmids could not be accurately typed using this method. Sixty-two plasmids carried more than one replicon, and these were significantly larger than those that carried a single replicon (Mann–Whitney U-test P < 0.0001, Fig. S21). Previous work has shown the propensity for blaNDM to be located on IncX3 plasmids, and our work supports this claim with 28% of blaNDM-carrying plasmids on an IncX3 plasmid. We also identify IncFII as a common replicon for blaNDM plasmids (25%) (Fig. 1; Table S31) (Wang et al. 2018). Additionally, we have identified multi-replicon plasmids, IncFIB, and IncN to be the common carriers for blaKPC, and IncA/C2 and IncN replicons as the common carriers for blaIMP (Table S31). Notably, most of the replicon types for blaVIM-resistance plasmids (38%) could not be identified using the PlasmidFinder database.

Fig. 1.

Relative abundance of incompatibility groups among plasmids. Predominant incompatibility groups from each carbapenemase family: KPC, IncFIB (15.8%), IncN (15.8%), and multi-replicon (17.3%); NDM, IncA/C2 (15.1%), IncFII (25.3%), IncX3 (28.3%), and multi-replicon (11.4%); IMP, IncA/C2 (22.4%), IncN (32.7%), and NA (8/49 16.3%); VIM, IncA/C2 (16.1%), IncN (13.8%), IncR (10.3%), and NA (37.9%).

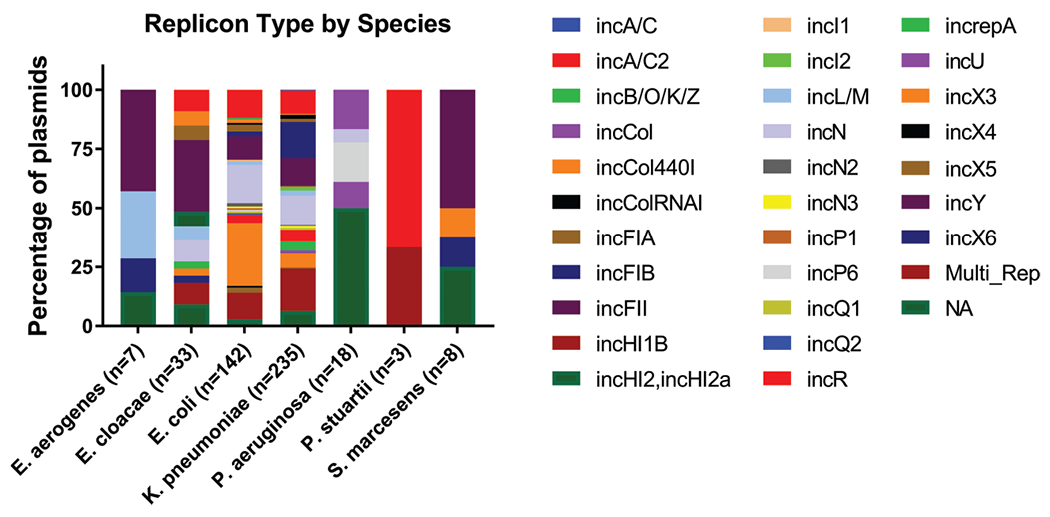

While the carbapenemases do not seem to be found more often on plasmids of a specific incompatibility group over another, there is a species preference, as would be expected (Fig. 2). With species that have more than five plasmids represented, E. cloacae, S. marcescens, and E. aerogenes more commonly contain IncFII plasmids (30%, 50%, and 43%, respectively); E. coli commonly contains IncX3 plasmids (27%); and K. pneumoniae are predominately carrying IncFIB, IncN, and multi-replicon plasmids (15%, 12%, and 18%, respectively). Most plasmids from P. aeruginosa could not be typed from the PlasmidFinder database since the database is designed for the family Enterobacteriaceae.

Fig. 2.

Relative abundance of incompatibility groups among bacterial species. Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens, and Enterobacter aerogenes prefer FII plasmids (30.3%, 50%, and 42.9%, respectively); Escherichia coli prefer X3 plasmids (26.8%); and FIB and multi-replicon plasmids predominate in Klebsiella pneumoniae (15.3% and 17.9%, respectively). Most plasmids from Pseudomonas aeruginosa could not be typed from the PlasmidFinder database (50%).

Of the incompatibility groups from multi-replicon plasmids, the most commonly found was IncFII, present in 48.4% of the plasmids. The other two most common incompatibility groups in multi-replicon plasmids are IncR and IncFIB (35.5% and 29.0%, respectively).

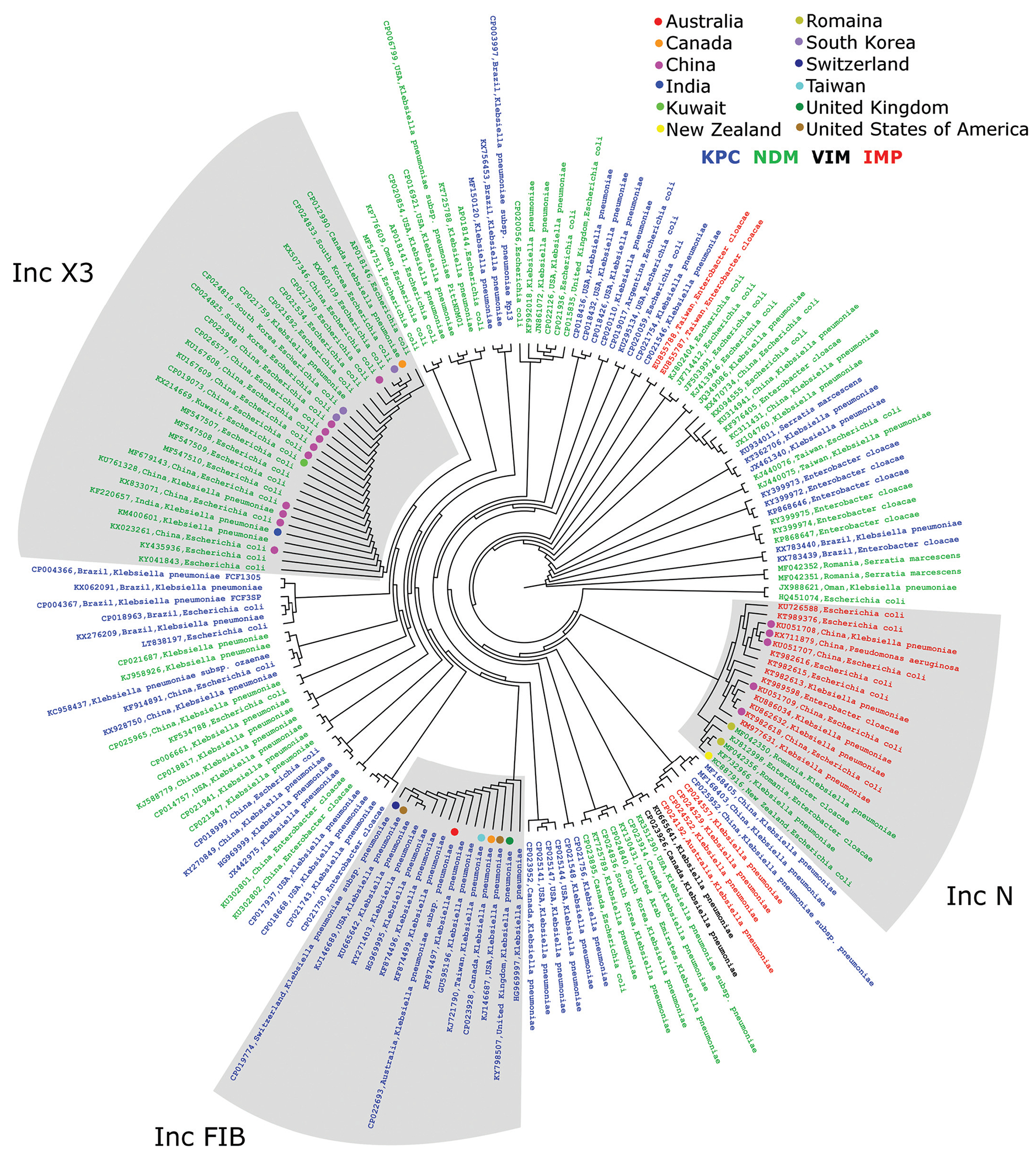

Geographic spread and species promiscuity of plasmids

Among all 446 plasmids, only 32 countries are represented, with the United States of America and China being the predominant countries (54 and 86, respectively). One hundred and ninety-four submissions did not list a country of origin for the plasmid. Additionally, of the 446 plasmids, our intra-BLAST analysis identified 42 indiscrete groups containing 114 plasmids (Fig. 3). The smallest groups contain 2 plasmids (23 groups) and the largest 48. In total, there were 332 discrete plasmids. Of the seven species of interest in this study, the greatest promiscuity has been seen between E. coli and K. pneumoniae, with the occasional coincident plasmid in E. cloacae and one incidence of an indiscrete plasmid shared between K. pneumoniae and S. marcescens. Twelve plasmids were of environmental or livestock origin, 139 were from clinical isolates, and the remaining 295 did not provide an isolation source.

Fig. 3.

Indiscrete plasmid groups. Cladogram showing the nucleotide relationships between plasmids that have >98% query coverage and identity. The geographic distribution of these plasmids in the three largest groups has been identified by colored dots. Blue text, KPC-carrying plasmid; green, NDM; red, IMP; black, VIM.

Additionally, according to this public data, China is the only country where all four carbapenemase types have been observed. In the following countries, three of the four carbapenemases were observed (not observed): Australia (blaVIM), Canada (blaIMP), Switzerland (blaIMP), Taiwan (blaVIM), and the United States of America (blaIMP). blaNDM was the most widespread carbapenemase, present in 25/32 countries. Interestingly, blaIMP was only reported from Asian and Oceanic countries (Australia, China, Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand).

Additionally, in countries that had at least 10 plasmids, we identified the predominant incompatibility group in that country (Table 1).

Table 1.

Predominant incompatibility group and carbapenemase prevalence in countries with more than 10 representative plasmids.

| Country | Incompatibility group | Percent of plasmids (no./total) | Percent carbapenemase gene in predominant incompatibility group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | IncFIB | 45.5% (5/11) | KPC 80.0% (4/5); IMP 20.0% (1/5) |

| Brazil | IncN | 50.0% (8/16) | KPC 100.0% (8/8) |

| Canada | IncFII | 33.3% (5/15) | KPC 40.0% (2/5); NDM 60.0% (3/5) |

| China | IncFII | 26.7% (23/86) | KPC 82.6% (19/23); NDM 17.4% (4/23) |

| United States of America | IncFIB | 24.1% (13/54) | KPC 61.5% (8/13); NDM 38.5% (5/13) |

Discussion

In general, data on carbapenemase-producing plasmids from less common but still clinically important organisms such as P. aeruginosa and relevant carbapenemases such as blaVIM is severely lacking. Additionally, global epidemiologic studies of carbapenemase-carrying plasmids are further complicated by the lack of GenBank metadata found. Differences between infection-reporting requirements and research efforts among different countries, and the fact that these plasmids are not routinely sequenced, further complicates these analyses.

The cladogram showing the nondiscrete plasmid groups (Fig. 3) is quite illuminating, but it is also the most biased due to large sequencing projects of local outbreaks. This may be the case for the over-representation of plasmids from China, especially the IncX3 group. However, the intercontinental nature of these nondiscrete plasmids, particularly the IncFIB group present on four separate continents, indicates either that these plasmids are very stable or that they can spread at a speed at which they do not accumulate significant mutations. Conversely, the fact that common incompatibility groups such as IncFII do not cluster with similar nondiscrete plasmids could be explained by them simply being more diverse or that they have not been identified during a sequencing project of a hospital CRE outbreak.

Furthermore, to effectively track and monitor the spread of carbapenem-resistance plasmids in local outbreaks, rapid identification is critical. Current clinical practices (blood culture, followed by isolation and PCR) have a 48–72 h delay before carbapenemase resistance is determined. For the more rapid, nonPCR-based methods using whole blood (such as Knob et al. 2018), it is important to realize that the plasmids of interest are quite large. With their median length over 80 kb, plasmid isolation becomes difficult when necessary for the application, and many of the replicon types identified are from low copy number plasmids.

Also, this report supports rational methods of several groups using targeted approaches to slow the spread of carbapenemase plasmids. First, the antitoxin of the plasmid addiction system is currently a target (Tsang 2017). Targeting this system could prevent its binding with the toxin, resulting in the death of the host harboring the plasmid. However, this would not be a universal target since only 52.9% of the plasmids contain toxin/antitoxin systems (Table S11). And secondly, 90.4% (403/446) of the plasmids carry transfer genes to pass the plasmid between bacteria (Table S11), which is also supported by the evidence shown here of nondiscrete plasmids appearing in multiple species. Preventing pilus formation could dramatically reduce the spread of these plasmids. This direction is currently being pursued by several groups employing strategies such as bacteriophage, colloidal clays, and antibody therapy (Getino and de la Cruz 2018). Targeting both mechanisms simultaneously may dramatically reduce the spread and persistence of these plasmids in the hospital.

Ultimately, this analysis was very difficult due to the nonstandardization of GenBank metadata and the under-reporting and publication of carbapenemase-carrying plasmids from different countries. This is a severe limitation in the complete comprehension of the carbapenem-resistance epidemic, and more effort needs to be focused on these under-reported carbapenemases and species (VIM and IMP, P. aeruginosa). However, we were able to support work done by other groups, by showing the prevalence of diverse targets (toxin/antitoxin and conjugal transfer) among these plasmids. These efforts may ultimately help stem the tide of increasing global carbapenem resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

G.E.C. conceptualized this analysis, determined the functional groups of interest, generated the key terms, and analyzed the output from the scripts. B.D.P. wrote the scripts for the analysis and assisted in writing a portion of the manuscript. P.G.R. and R.A.R. advised this work and reviewed the manuscript. We thank the Fulton Supercomputing Laboratory (https://marylou.byu.edu) at Brigham Young University for their consistent efforts to support our research. We would also like to thank the curators of the PlasmidFinder database (Henrik Hasman and Alessandra Carattoli) for keeping that information up to date and accessible. This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01 AI116989).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data are available with the article through the journal Web site at http://nrcresearchpress.com/doi/suppl/10.1139/gen-2019-0100.

Contributor Information

Galen E. Card, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA.

Brandon D. Pickett, Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA.

Perry G. Ridge, Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA

Richard A. Robison, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, and Lipman DJ 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol 215: 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold RS, Thom KA, Sharma S, Phillips M, Johnson JK, and Morgan DJ 2011. Emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-producing bacteria. South. Med. J 104(1):40–45. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181fd7d5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedenić B, Plečko V, Sardelić S, Uzunović S, and Godič Torkar K 2014. Carbapenemases in gram-negative bacteria: laboratory detection and clinical significance. BioMed Res. Int 2014: 841951. doi: 10.1155/2014/841951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, and Madden TL 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 10: 421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, et al. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 58(7): 3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. n.d. Tracking CRE [online]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cre/trackingcre.html [accessed 8 June 2018].

- Chen FJ, Huang WC, Liao YC, Wang HY, Lai JF, Kuo SC, et al. 2019. Molecular epidemiology of emerging carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter nosocomialis and Acinetobacter pittii in Taiwan, 2010–2014. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother doi: 10.1128/aac.02007-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codjoe FS, and Donkor ES 2018. Carbapenem resistance: a review. Med. Sci 6(1). doi: 10.3390/medsci6010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getino M, and de la Cruz F 2018. Natural and artificial strategies to control the conjugative transmission of plasmids. Microbiol. Spectrum, 6(1). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MTBP-0015-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AP, and Woodford N 2013. Global spread of antibiotic resistance: the example of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM)-mediated carbapenem resistance. J. Med. Microbiol 62: 499–513. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.052555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, and Cardo DM 2007. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Reports, 122(2): 160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knob R, Hanson RL, Tateoka OB, Wood RL, Guerrero-Arguero I, Robison RA, et al. 2018. Sequence-specific sepsis-related DNA capture and fluorescent labeling in monoliths prepared by single-step photopolymerization in microfluidic devices. Journal of Chromatography A, 1562: 12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan LK, and Weinstein RA 2017. The epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the impact and evolution of a global menace. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 215(suppl_1): S28–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, et al. 2014. Multistate Point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(13): 1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour W, Grami R, Jaidane N, Messaoudi A, Charfi K, Ben Romdhane L, et al. 2019. Epidemiology and whole-genome analysis of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae KP3771 from Tunisia. Microb. Drug Resist 25(5). doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsik FJ, and Nambiar S 2011. Review of carbapenemases and AmpC-beta-lactamases. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J 30(12): 1094–1095. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31823c0e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB, McKinnon LM, Whiting MF, and Ridge PG 2019. CAM: an alignment-free method to recover phylogenies using codon aversion motifs. PeerJ. 7: e6984. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Bhattacharjee A, Naha S, Majumdar T, Debbarma SK, Kaur H, et al. 2019. Molecular characterization of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST29, ST347, ST1224, and ST2558 causing sepsis in neonates in a tertiary care hospital of North-East India. Infect. Genet. Evol 69: 166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlek A, Phan H, Sheppard AE, Doumith M, Ellington M, Peto T, et al. 2017. Ordering the mob: insights into replicon and MOB typing schemes from analysis of a curated dataset of publicly available plasmids. Plasmid, 91:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overturf GD 2010. Carbapenemases: a brief review for pediatric infectious disease specialists. Pediatric Infect. Disease J 29(1): 68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DL, and Bonomo RA 2005. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 18(4): 657–686. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez F, and Van Duin D 2013. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a menace to our most vulnerable patients. Cleveland Clin. J. Med 80(4): 225–233. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.80a.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza A, Comandatore F, Romeri F, Brilli M, Dichirico B, Ridolfo A, et al. 2019. Identification of blaVIM-1 gene in ST307 and ST661 Klebsiella pneumoniae clones in Italy: old acquaintances for new combinations. Microb. Drug Resist 25(5): 787–790. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Potron A, and Nordmann P 2012. OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J. Antimicrob. Chem 67(7): 1597–1606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read AF, and Woods RJ 2014. Antibiotic resistance management. Evol. Med. Publ. Health, 2014(1): 147–147. doi: 10.1093/emph/eou024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard AE, Stoesser N, Wilson DJ, Sebra R, Kasarskis A, Anson LW, et al. 2016. Nested Russian doll-like genetic mobility drives rapid dissemination of the carbapenem resistance gene blaKPC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 60(6): 3767–3778. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00464-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotgiu G, Are BM, Pesapane L, Palmieri A, Muresu N, Cossu A, et al. 2018. Nosocomial transmission of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in an Italian university hospital: a molecular epidemiological study. J. Hosp. Infect 99(4): 413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Peirano G, Anson LW, Pankhurst L, Sebra R, et al. 2017. Genomic epidemiology of global Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep 7(1): 5917. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06256-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall BJ, Sutton G, and Garrity GM 2017. Enterobacter aerogenes Hormaeche and Edwards 1960 (Approved Lists 1980) and Klebsiella mobilis Bascomb et al. 1971 (Approved Lists 1980) share the same nomenclatural type (ATCC 13048) on the Approved Lists and are homotypic synonyms, with consequences for the name Klebsiella mobilis Bascomb et al. 1971 (Approved Lists 1980). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 67(2): 502–504. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang J 2017. Bacterial plasmid addiction systems and their implications for antibiotic drug development. Postdoc J. 5(5): 3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Tong M-K, Chow K-H, Cheng VC-C, Tse CW-S, Wu AK-L, et al. 2018. Occurrence of highly conjugative IncX3 epidemic plasmid carrying blaNDM in Enterobacteriaceae isolates in geographically widespread areas. Front. Microbiol 9: 2272. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Iyobe S, Inoue M, and Mitsuhashi S 1991. Transferable imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 35(1): 147–151. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yigit H, Queenan AM., Anderson GJ, Domenech-Sanchez A, Biddle JW, Steward CD, et al. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 45(4): 1151–1161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee K, and Walsh TR 2009. Characterization of a new metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaNDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53(12): 5046–5054. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.