Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent neural disorder. However, the therapeutic agents for AD are limited. Eucommia ulmoides Olive (EUO) is widely used as a traditional Chinese herb to treat various neurodegenerative disorders. Therefore, we investigated whether the extracts of EUO male flower (EUMF) have therapeutic effects against AD. We focused on the flavonoids of EUMF and identified the composition using a targeted HPLC-MS analysis. As a result, 125 flavonoids and flavanols, 32 flavanones, 22 isoflavonoids, 11 chalcones and dihydrochalcones, and 17 anthocyanins were identified. Then, the anti-AD effects of the EUMF were tested by using zebrafish AD model. The behavioral changes were detected by automated video-tracking system. Aβ deposition was assayed by thioflavin S staining. Ache activity and cell apoptosis in zebrafish were tested by, Acetylcholine Assay Kit and TUNEL assay, respectively. The results showed that EUMF significantly rescued the dyskinesia of zebrafish and inhibited Aβ deposition, Ache activity, and occurrence of cell apoptosis in the head of zebrafish induced by AlCl3. We also investigated the mechanism underlying anti-AD effects of EUMF by RT-qPCR and found that EUMF ameliorated AD-like symptoms possibly through inhibiting excessive autophagy and the abnormal expressions of ache and slc6a3 genes. In summary, our findings suggested EUMF can be a therapeutic candidate for AD treatment.

Keywords: AD, AlCl3, Ache, slc6a3, flavonoids

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a common neurodegenerative disease which is age-related. Patients with AD are characterized by the progressive loss of acquired knowledge and memory decline. The loss of neurons, formation of neurofibrillary tangles, tau protein aggregation, amyloid β-protein (Aβ) deposition, and low levels of acetylcholine (ACh) are the main clinical hallmarks of AD (Kepp, 2016; Sanabria-Castro et al., 2017).

The aging tendency of the population is leading to an increased prevalence of AD. Currently, over 47 million people have been diagnosed with AD, and this has caused heavy burdens for families and society (Neves et al., 2021). To deal with this situation, many AD drugs have been developed, such as anti-tau, an amyloid β-protein (Aβ) aggregation inhibitor, and cholinergic-enhancing and anti-inflammatory drugs. Unfortunately, these drugs are not able to prevent the progression of AD and only can improve cognitive function and memory to a certain extent (Pearson, 2001; Huang and Mucke, 2012). Therefore, the development of AD drugs is an urgent task.

Because of their novel structures and extensive physiological activities, natural products from plants have been always an important source of drug development. Eucommia ulmoides Olive (EUO), also named Du-zhong, is a deciduous tree in the family of Eucommiaceae (Yan et al., 2018). It is also the traditional Chinese herb. The leaf and bark of EUO are officially documented in the Chinese Pharmacopeia. The leaf extracts of EUO are reported to be treat AD, aging, diabetes, hypertension, and osteoporosis (He et al., 2014). However, studies investigating the male flowers of EUO began relatively late. Currently, many studies have shown that the male flowers, like the leaf and bark of EUO, also contain many bioactive components including lignans, megastigmane glycosides, iridoids, phenolics, and flavonoids. These bioactive constituents have typically exhibited neuroprotective, anti-oxidant, anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-hypertensive, anti-aging, immunity promotion, and other activities (Luo et al., 2010; Kobayashi et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Niu et al., 2015; Hao et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2018). There are similar bioactive constituents between the male flower and leaf of EUO. Hence, we hypothesize that extracts of the EUO male flower (hereafter referred to as EUMF) may have anti-AD activity.

Zebrafish is an ideal model system for human disease and drug development. They possess a high homology to humans and have rapid development and small sizes (Kerstin et al., 2013; Hong et al., 2020). Many studies have reported that a zebrafish AD model can be established by using AlCl3, an in vivo animal model that can mirror the primary characteristic pathological changes of patients with AD. Various clinical hallmarks of AD can be detected in this model (Huang et al., 2016; Pan et al., 2019). But unfortunately, an important clinical hallmark-Aβ deposition has not yet been successfully detected in zebrafish AD model.

In summary, in this study we isolated and purified the EUMF and identified the chemical compositions. To verify our hypothesis mentioned in the previous paragraph, the zebrafish AD model was used to investigate the therapeutic effect of EUMF on AD symptoms. In addition, Aβ deposition detection was used innovatively in our zebrafish AD model. Finally, we further tested the mRNA expressions of key factors involved in autophagy and the regulation of neurotransmitters to reveal the underlying mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The adult wild-type zebrafish (AB strain) were maintained in a zebrafish facility at 28.5°C ± 0.5°C with a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle photoperiod at the Key Laboratory for Drug Screening Technology of the Shandong Academy of Sciences. Larvae were obtained from natural mating. Zebrafish larvae at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf) were used this study. All experiments were conducted in compliance with the standard ethical guidelines and under the control of the Biology Institute, the Qilu University of Technology of Animal Ethics Committee.

Preparation of the Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower

The hydrothermal extraction method is used to prepare EUMF. Approximately 20 g of dried EUMF powder was placed into a flask, and 2,000 mL of ultrapure water was added. Then the flask was placed into an electric jacket for extraction by heat reflux three times, 2 h each time. The supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. The combined extraction solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation and then freeze-dried to obtain the EUMF.

Identification of Flavonoid Compounds Using HPLC-MS

A targeted HPLC-MS analysis of the flavonoid compounds was performed on SCIEX Qtrap 6500 + system (SCIEX, United States). The Xselect HSS T3 C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 2.5 μm) was used for sample separation. Distilled water containing 0.1% formic acid was used as solvent A, and acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid was used as solvent B. The elution condition was maintained at 2% B for 2 min, from 2 to 100% B for 13 min, maintained at 100% B for 2 min, and equilibrated with the initial elution solvent for 3 min. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. The injection volume of the sample was 1 μL. The column temperature was set to be 50°C. Mass spectrometry was performed in both the positive and negative ion modes. The optimal positive MS parameters were a curtain gas pressure of 35 psig and an ion spray voltage of 5,500 V at a temperature of 550°C. For the negative MS mode, the ion spray voltage was set as −4,500 V and the other parameter was the same as the positive mode. All of the compounds were identified according to LC and MS information and compared with flavonoid compound databases that were supplied by the Novogene Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China).

Establishment of Zebrafish Alzheimer’s Disease Model

The establishment of the zebrafish AD model referenced to the previous studies (Huang et al., 2016; Pan et al., 2019) with a slight modification. In brief, 3 dpf larval zebrafish were randomly transferred to six-well cell culture plates with a density of approximately 20 larvae per well. Then they were treated with 80 μM AlCl3 from 3 to 6 dpf to generate the zebrafish AD models.

Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower and Donepezil Treatments

The larvae were treated with different concentrations of EUMF (100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, and 1,600 μg/mL) from 3 to 6 dpf. We found that the LC1 and LC50 of the EUMF were 206 and 454 μg/mL, respectively, based on the EUMF lethality curve of Figure 1A. LC1 is typically regarded as a no-observed-effect concentration value. Therefore, we tested the anti-AD activity of the EUMF at concentrations below LC1 (206 μg/mL). The zebrafish larvae were co-treated with 80 μM AlCl3 and EUMF at three different concentrations (50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) from 3 to 6 dpf (Figure 1B). Donepezil which is the inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase (Ache) was used as the positive drug. In the positive group, the larvae were co-treated with 80 μM AlCl3 and 4.0 μM donepezil from 3 to 6 dpf. After treatment, 10 larvae from each group were randomly selected for the image acquisition.

FIGURE 1.

Mortality curve and experimental workflow chart. (A) Larval zebrafish were exposed to different concentrations of EUMF (100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, and 1,600 μg/mL) from 3 to 6 dpf. The mortality was recorded within each group at 3, 4, 5, and 6 dpf. Dead larvae were judged using missing heartbeats. (B) Larvae at 3 dpf were co-exposed to AlCl3 and three different concentrations of EUMF from 3 to 6 dpf. At 6 dpf the zebrafish were subjected to a behavioral test. In addition, we also evaluated the AchE activity, Aβ deposition, and apoptosis in the brain and performed RT-qPCR.

Behavioral Analysis

The larvae from each group were randomly collected, and cleaned using an embryo medium (1 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 0.05 mM (NH4)3PO4, 0.15 mM KH2PO4, 0.7 mM NaHCO3, and 1 mM CaCl2). They were then placed in 48-well plates. After a 20-min acclimation period, the locomotor activity for each larva was recorded using an automated computerized video-tracking system (Viewpoint, Lyon, France). The behavioral tests contained three alternating light-dark cycles with 60 min (10 min illumination, 10 min darkness alternately). Zeblab software (Viewpoint, Lyon, France) was used to recorded and analyzed the zebrafish movement distance and speed change to light-dark and dark-light cycles.

Detection of the Amyloid β-Protein Deposition

The zebrafish larvae were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde. All of the fixed zebrafish were processed by embedding in the optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT Compound, SAKURA, United States) and frozen at −20°C until sectioning. Subsequently, the tissue sections were used for thioflavin S staining (Chao et al., 2018). In brief, the sections were washed with 0.01 M phosphate buffered solution (PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Next, 0.3% thioflavin S (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was introduced, and the sections were incubated for 8 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, the sections were washed with 0.01 M PBS for 30 min in dark, and a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used to analyze the sections. The fluorescence intensity of the Aβ deposition in the head was measured using Image-Pro Plus version 5.1.

Determination of Ache Activity

After co-treatment with AlCl3 and EUMF, zebrafish larvae at 6 dpf were killed by tricaine (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). Cold physiological saline was added to the larvae in a 2 mL tube at a ratio of 1:9 (mass:volume) without any additional water. Next, the samples were homogenized using automated tissue homogenization, followed by centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 10 min at 0°C. The supernatant was collected for the assay. The enzyme activity of Ache was determined by using the Amplite™ Fluorimetric Acetylcholinesterase Assay Kit (AAT Bioquest, California, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a slight modification as follows. The acetylthiocholine reaction mixture was 50 μM.

The test samples addition added into the acetylthiocholine reaction mixture was also 50 μM. The fluorescence at Ex/Em = 490/520 was monitored.

Apoptosis Assessment

Apoptotic cells in the head were assessed using the One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China). Briefly, the zebrafish larvae at 6 dpf were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Next, they were blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol and incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture. The larvae were photographed by using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The fluorescence intensities of apoptotic cells in the head were measured using Image-Pro Plus version 5.1.

Detection of Gene Expression

The expression of six genes: autophagy and beclin 1 regulator 1a (ambra1a), autophagy-related gene 5 (atg5), unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ulk1b), autophagy-related ubiquitin-like modifier LC3 B (lc3b), acetylcholinesterase (ache), and solute carrier family 6 member 3 (slc6a3) were detected in the zebrafish larvae using RT-qPCR. The total RNA was extracted from the larval tissue using the EASY spin Plus RNA Mini Kit (Aidlab Biotechnologies, Beijing, China) according to manufacturer instructions. Next, RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), The RT-qPCR was conducted using the SYBR® Premix DimerEraser™ (Takara Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The housekeeping gene, rpl13a, was used as a reference gene. The primer sequences of the above genes are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

The sequences of primer pairs used in real-time quantitative PCR assay.

| No | Gene symbol | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| 1 | ambra1a | TAACCAGGAAACTGGCCAAC | AATATGCTGCAGGGGACAAC |

| 2 | atg5 | AGGGGATAACAGCACAAACG | CTTCTTATGCAGCGTGTCCA |

| 3 | ulk1b | AGGCCGAAAGTCTCACTTCA | AGCCATGTACATCGGAGACC |

| 4 | lc3b | CCTCCAACTCAACTCCAACC | GCCGTCTTCGTCTCTTTCC |

| 5 | ache | TCTTGCCCACTGTGCTACTC | TCTTGTACCCTGCACTCTGC |

| 6 | slc6a3 | CTAATCGCCTTCTCCAGCTACA | GGCCACGTTGTGTTTCTGTGACAT |

| 7 | rpl13a | TCTGGAGGACTGTAAGAGGTATGC | AGACGCACAATCTTGAGAGCAG |

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SEM. The statistical analyses were conducted using Graph Pad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA, United States) by a one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. If the P-value was less than 0.05, the difference was considered as significant.

Results

Flavonoids Compounds Analysis of the Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower

A large number of literature studies have shown that flavonoids show neuroprotective effects against AD (Remya et al., 2012; Remya et al., 2014; Bakhtiari et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021; Noori et al., 2021; Pragya and Arun, 2021). Thus, the flavonoids were selected as the primary components of EUMF for further study. The total contents of the EUMF flavonoids were determined according to the obtained standard curves of the total flavonoids which was reported in a previous study from our lab (Zhang et al., 2020). According to regression equations (y = 0.0003x + 0.0107), the total contents of the EUMF flavonoids were 45.99 ± 0.5853 mg/g. Moreover, the targeted LC-MS analysis of the flavonoids showed that total 206 compounds were detected (Table 2). Among them, 125 flavonoids and flavanols, 32 flavanones, 22 isoflavonoids, 11 chalcones and dihydrochalcones, and 17 anthocyanins were identified. In addition, quercetin-3′-O-glucoside (relative content of 9.1850%), isoquercitrin (8.8025%), rutin hydrate (8.0753%), rutin (7.9072%), spiraeoside (7.5218%), isotrifoliin (7.3683%), isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside (6.5757%), naringenin (5.7225%), naringenin chalcone (5.6733%), butin, myricitrin, isomucronulatol-7-O-glucoside, hyperoside, hesperetin 5-O-glucoside, narcissoside, di-O-methylquercetin, lonicerin and morin were the primary components of EUMF. The relative content of these 18 components accounted for greater than 90% of the total flavonoids.

TABLE 2.

Flavonoids compounds identified in EUMF by LC-MS.

| No | RT (min) | Molecular Weight | Formula | Name | Relative content (%) | Class |

| 1 | 0.680 | 274.084 | C15H14O5 | Afzelechin | 0.0854 | Flavonoids |

| 2 | 0.700 | 420.454 | C25H24O6 | Kuwanon A | 0.0064 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 3 | 0.710 | 448.400 | C22H22O11 | Methylluteolin C-hexoside | 0.0210 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 4 | 0.720 | 418.100 | C21H22O9 | O-methylnaringenin C-pentoside | 0.2106 | Flavanones |

| 5 | 0.720 | 418.394 | C21H22O9 | Methylnaringenin C-pentoside | 0.2024 | Flavanones |

| 6 | 0.730 | 402.350 | C20H18O9 | Apigenin C-pentoside | 0.0411 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 7 | 0.730 | 446.404 | C22H22O10 | Methylapigenin C-hexoside | 0.0837 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 8 | 0.730 | 550.460 | C25H26O14 | di-C, C-pentosyl-luteolin | 0.0554 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 9 | 0.740 | 478.400 | C22H22O12 | Selgin C-hexoside | 0.0150 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 10 | 0.780 | 342.343 | C19H18O6 | Methylophiopogonanone A | 0.0025 | Isoflavonoids |

| 11 | 0.940 | 478.400 | C22H22O12 | Selgin 5-O-hexoside | 0.0348 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 12 | 0.950 | 272.069 | C15H12O5 | Butein | 0.0093 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 13 | 0.970 | 476.430 | C23H24O11 | Irisolidone 7-O-beta-d-glucoside | 0.0106 | Isoflavonoids |

| 14 | 0.970 | 476.430 | C23H24O11 | Methylchrysoeriol 5-O-hexoside | 0.0136 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 15 | 0.970 | 508.430 | C23H24O13 | Limocitrin O-hexoside | 0.0236 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 16 | 0.980 | 756.660 | C33H40O20 | C-hexosyl-apigenin O-hexosyl-O-hexoside | 0.0048 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 17 | 0.980 | 479.000 | C22H23O12 | Petunidin 3-O-glucoside | 0.0489 | Anthocyanins |

| 18 | 1.000 | 624.552 | C28H32O16 | C-hexosyl-chrysoeriol O-hexoside | 0.0105 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 19 | 1.010 | 286.279 | C16H14O5 | Sakuranetin | 0.0118 | Flavanones |

| 20 | 1.010 | 416.378 | C21H20O9 | Methylapigenin C-pentoside | 0.0043 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 21 | 1.040 | 430.405 | C22H22O9 | Ononin | 0.0468 | Isoflavonoids |

| 22 | 1.130 | 868.702 | C43H32O20 | 8-Gingerol | 0.0069 | Flavonoids |

| 23 | 1.220 | 576.500 | C30H24O12 | Procyanidin A1 | 0.0009 | Anthocyanins |

| 24 | 1.260 | 576.500 | C30H24O12 | Procyanidin A2 | 0.0011 | Anthocyanins |

| 25 | 1.284 | 254.240 | C15H10O4 | Chrysin | 0.0004 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 26 | 2.600 | 332.262 | C16H12O8 | Laricitrin | 0.4216 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 27 | 4.440 | 302.279 | C16H14O6 | Homoeriodictyol | 0.0003 | Flavanones |

| 28 | 4.560 | 302.043 | C15H10O7 | Tricetin | 0.0003 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 29 | 5.098 | 306.270 | C15H14O7 | (-)-epigallocatechin | 0.0005 | Flavonoids |

| 30 | 5.210 | 484.840 | C21H21ClO11 | Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | 0.0111 | Anthocyanins |

| 31 | 5.213 | 484.840 | C21H21ClO11 | Idaein chloride | 0.0081 | Anthocyanins |

| 32 | 5.310 | 466.392 | C21H22O12 | Taxifolin O-glucoside | 0.0064 | Flavanones |

| 33 | 5.380 | 356.332 | C19H16O7 | Ophiopogonanone C | 0.2663 | Flavanones |

| 34 | 5.390 | 626.520 | C27H30O17 | Quercetin-3,4′-O-di-beta-glucopyranoside | 0.3593 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 35 | 5.420 | 809.120 | C33H41O21Cl1 | Delphinidin 3-sophoroside-5-rhamnoside | 0.0329 | Anthocyanins |

| 36 | 5.442 | 468.840 | C21H21ClO10 | Callistephin chloride | 0.0005 | Anthocyanins |

| 37 | 5.515 | 528.890 | C23H25ClO12 | Malvidin 3-galactoside chloride | 0.0005 | Anthocyanins |

| 38 | 5.572 | 528.890 | C23H25ClO12 | Oenin chloride | 0.0022 | Anthocyanins |

| 39 | 5.602 | 338.700 | C15H11ClO7 | Delphinidin chloride | 0.0009 | Anthocyanins |

| 40 | 5.680 | 610.518 | C27H30O16 | C-hexosyl-luteolin O-hexoside | 0.0012 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 41 | 5.730 | 594.518 | C27H30O15 | Apigenin-6,8-di-C-glycoside | 0.1253 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 42 | 5.745 | 432.380 | C21H20O10 | Puerarin | 0.0031 | Isoflavonoids |

| 43 | 5.810 | 624.544 | C28H32O16 | di-C,C-hexosyl-methylluteolin | 0.1441 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 44 | 5.820 | 594.518 | C27H30O15 | di-C,C-hexosyl-apigenin | 0.2993 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 45 | 5.890 | 288.252 | C15H12O6 | Fustin | 0.0043 | Flavanones |

| 46 | 6.030 | 564.499 | C26H28O14 | Isoschaftoside | 0.0142 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 47 | 6.040 | 594.526 | C27H30O15 | C-pentosyl-chrysoeriol O-hexoside | 0.0236 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 48 | 6.050 | 564.490 | C26H28O14 | C-pentosyl-C-hexosyl-apigenin | 0.0028 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 49 | 6.074 | 564.492 | C26H28O14 | Schaftoside | 0.0828 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 50 | 6.080 | 430.628 | C27H42O4 | Hecogenin | 0.0367 | Flavonoids |

| 51 | 6.090 | 466.398 | C21H22O12 | Plantagoside | 0.0256 | Flavanones |

| 52 | 6.100 | 448.400 | C21H20O11 | Luteolin C-hexoside derivative | 0.2109 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 53 | 6.174 | 448.380 | C21H20O11 | Isoorientin | 0.0972 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 54 | 6.230 | 416.378 | C21H20O9 | Toringin | 0.0272 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 55 | 6.230 | 446.121 | C22H22O10 | Sissotrin | 0.0007 | Isoflavonoids |

| 56 | 6.250 | 448.377 | C21H20O11 | Orientin | 0.0972 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 57 | 6.263 | 322.700 | C15H11ClO6 | Cyanidin chloride | 0.0007 | Anthocyanins |

| 58 | 6.270 | 594.518 | C27H30O15 | Saponarin | 0.0360 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 59 | 6.280 | 610.525 | C27H30O16 | Kaempferol-3-gentiobioside | 0.0200 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 60 | 6.280 | 594.518 | C27H30O15 | 4′-O-Glucosylvitexin | 0.0360 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 61 | 6.300 | 578.519 | C27H30O14 | 6”-O-xylosyl-glycitin | 0.0023 | Isoflavonoids |

| 62 | 6.350 | 611.500 | C27H31O16 | Tulipanin | 0.3871 | Anthocyanins |

| 63 | 6.360 | 610.520 | C27H30O16.xH2O | Rutin hydrate | 8.0753 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 64 | 6.380 | 596.542 | C27H32O15 | Neoeriocitrin | 0.4294 | Flavanones |

| 65 | 6.390 | 434.121 | C21H22O10 | Isohemiphloin | 0.0171 | Flavanones |

| 66 | 6.411 | 578.520 | C27H30O14 | Vitexin-2-O-rhaMnoside | 0.0026 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 67 | 6.430 | 612.576 | C28H36O15 | Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone | 0.1784 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 68 | 6.430 | 596.534 | C27H32O15 | Eriocitrin | 0.0007 | Flavanones |

| 69 | 6.451 | 610.518 | C27H30O16 | Rutin | 7.9072 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 70 | 6.460 | 432.113 | C21H20O10 | Apigenin C-glucoside | 0.0009 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 71 | 6.470 | 208.255 | C15H12O | Chalcone | 0.5983 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 72 | 6.510 | 594.526 | C27H30O15 | Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | 0.0309 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 73 | 6.530 | 462.366 | C21H18O12 | Luteolin-7-O-beta-D-glucuronide | 0.0017 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 74 | 6.530 | 464.382 | C21H20O12 | Quercetin-3′-O-glucoside | 9.1850 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 75 | 6.530 | 464.469 | C23H28O10 | Isomucronulatol-7-O-glucoside | 3.3727 | Isoflavonoids |

| 76 | 6.533 | 432.378 | C21H20O10 | Isovitexin | 0.0007 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 77 | 6.540 | 464.376 | C21H20O12 | Quercetin-O-glucoside | 0.4630 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 78 | 6.547 | 464.380 | C21H20O12 | Myricitrin | 4.7113 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 79 | 6.550 | 594.159 | C27H30O15 | Kaempferol 3-O-robinobioside | 0.4242 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 80 | 6.554 | 464.380 | C21H20O12 | Hyperoside | 2.9062 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 81 | 6.559 | 432.380 | C21H20O10 | Vitexin | 0.0006 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 82 | 6.581 | 446.404 | C22H22O10 | Calycosin-7-O-beta-D-glucoside | 0.0027 | Isoflavonoids |

| 83 | 6.590 | 464.419 | C22H24O11 | Hesperetin 5-O-glucoside | 1.6133 | Flavanones |

| 84 | 6.590 | 464.096 | C21H20O12 | Spiraeoside | 7.5218 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 85 | 6.590 | 464.096 | C21H20O12 | Isotrifoliin | 7.3683 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 86 | 6.590 | 462.360 | C21H18O12 | Scutellarin | 0.0010 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 87 | 6.596 | 464.380 | C21H20O12 | Isoquercitrin | 8.8025 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 88 | 6.620 | 448.101 | C21H20O11 | Trifolin | 0.1696 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 89 | 6.620 | 448.383 | C21H20O11 | Luteoloside | 0.1774 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 90 | 6.650 | 448.377 | C21H20O11 | Kaempferol7-O-beta-D-glucopyranoside | 0.1172 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 91 | 6.664 | 448.380 | C21H20O11 | Luteolin 7-O-glucoside | 0.1331 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 92 | 6.680 | 432.380 | C21H20O10 | Apigenin 5-O-glucoside | 0.0666 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 93 | 6.720 | 462.404 | C22H22O11 | Chrysoeriol C-hexoside | 0.0445 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 94 | 6.730 | 594.526 | C27H30O15 | Lonicerin | 1.4742 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 95 | 6.780 | 625.560 | C28H33O16 | Petunidin 3-O-rutinoside | 0.0030 | Anthocyanins |

| 96 | 6.780 | 432.380 | C21H20O10 | Genistin | 0.0018 | Isoflavonoids |

| 97 | 6.790 | 624.552 | C28H32O16 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside | 6.5757 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 98 | 6.825 | 624.544 | C28H32O16 | Narcissoside | 1.5707 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 99 | 6.837 | 580.535 | C27H32O14 | Narirutin | 0.0171 | Flavanones |

| 100 | 6.840 | 578.520 | C27H30O14 | Isorhoifolin | 0.1097 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 101 | 6.860 | 462.410 | C22H22O11 | Pratensein-7-O-glucoside | 0.1006 | Isoflavonoids |

| 102 | 6.864 | 462.400 | C22H22O11 | Tectoridin | 0.0013 | Isoflavonoids |

| 103 | 6.880 | 316.262 | C16H12O7 | Rhamnetin | 0.0394 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 104 | 6.885 | 304.250 | C15H12O7 | Taxifolin | 0.2520 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 105 | 6.900 | 268.269 | C16H12O4 | Tectochrysin | 0.0005 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 106 | 6.910 | 306.700 | C15H11ClO5 | Pelargonidin chloride | 0.0008 | Anthocyanins |

| 107 | 6.940 | 608.545 | C28H32O15 | Chrysoeriol 7-O-rutinoside | 0.0021 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 108 | 6.940 | 578.520 | C27H30O14 | Rhoifolin | 0.2416 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 109 | 6.970 | 270.241 | C15H10O5 | 6,7,4′-Trihydroxyisoflavone | 0.0012 | Isoflavonoids |

| 110 | 6.970 | 448.383 | C21H20O11 | Vincetoxicoside B | 0.0033 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 111 | 6.979 | 580.530 | C27H32O14 | Naringin | 0.0110 | Flavanones |

| 112 | 6.980 | 418.390 | C21H22O9 | Liquiritin | 0.0054 | Flavanones |

| 113 | 7.010 | 502.200 | C26H30O10 | Phellodensin F | 0.0034 | Flavanones |

| 114 | 7.020 | 434.121 | C21H22O10 | Prunin | 0.0868 | Flavanones |

| 115 | 7.038 | 432.380 | C21H20O10 | Sophoricoside | 0.0075 | Isoflavonoids |

| 116 | 7.060 | 272.069 | C15H12O5 | Pinobanksin | 0.1659 | Flavanones |

| 117 | 7.080 | 446.367 | C21H18O11 | Apigenin7-O-beta-D-glucuronide | 0.0006 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 118 | 7.080 | 418.351 | C20H18O10 | Kaempferol 3-A-L-Arabinopyranoside | 0.0060 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 119 | 7.080 | 432.420 | C22H24O9 | Heptamethoxyflavone | 0.0076 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 120 | 7.080 | 434.400 | C21H20O10 | Resokaempferol 7-O-hexoside | 0.0077 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 121 | 7.120 | 608.545 | C28H32O15 | Neodiosmin | 0.0006 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 122 | 7.120 | 536.000 | C24H24O14 | Eriodictyol O-malonylhexoside | 0.0030 | Flavanones |

| 123 | 7.180 | 462.404 | C22H22O11 | Chrysoeriol 5-O-hexoside | 0.0047 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 124 | 7.186 | 462.403 | C22H22O11 | Homoplantaginin | 0.0058 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 125 | 7.190 | 480.376 | C21H20O13 | Myricetin 3-O-galactoside | 0.0185 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 126 | 7.190 | 492.430 | C23H24O12 | Tricin 5-O-hexoside | 0.0017 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 127 | 7.200 | 610.560 | C28H34O15 | Neohesperidin | 0.0461 | Flavanones |

| 128 | 7.200 | 448.400 | C22H22O11 | Chrysoeriol 7-O-hexoside | 0.0087 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 129 | 7.240 | 448.380 | C21H20O11 | Quercitrin | 0.0074 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 130 | 7.240 | 436.410 | C21H24O10 | Phlorizin | 0.0718 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 131 | 7.300 | 476.430 | C23H24O11 | Methylchrysoeriol C-hexoside | 0.0030 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 132 | 7.320 | 526.490 | C27H26O11 | Tricin 4′-O-(beta-guaiacylglyceryl) ether | 0.0316 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 133 | 7.340 | 318.240 | C15H10O8 | Myricetin | 0.0088 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 134 | 7.350 | 432.106 | C21H20O10 | Kaempferin | 0.0009 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 135 | 7.360 | 432.106 | C21H20O10 | Kaempferol 7-O-rhamnoside | 0.0007 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 136 | 7.372 | 582.550 | C27H34O14 | Naringin dihydrochalcone | 0.0001 | Flavanones |

| 137 | 7.400 | 688.639 | C33H36O16 | Tricin 4′-O-(β-guaiacylglyceryl) ether O-hexoside | 0.0165 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 138 | 7.417 | 286.240 | C15H10O6 | Fisetin | 0.0190 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 139 | 7.471 | 418.394 | C21H22O9 | Isoliquiritin | 0.0068 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 140 | 7.500 | 330.289 | C17H14O7 | Tricin | 0.1054 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 141 | 7.500 | 578.470 | C26H26O15 | Tricin O-malonylhexoside | 0.0295 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 142 | 7.510 | 688.630 | C33H36O16 | Tricin 4′-O-(beta-guaiacylglyceryl) ether 5-O-hexoside | 0.0137 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 143 | 7.523 | 436.409 | C21H24O10 | Trilobatin | 0.0356 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 144 | 7.575 | 446.360 | C21H18O11 | Baicalin | 0.0095 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 145 | 7.635 | 286.236 | C15H10O6 | Scutellarein | 0.0022 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 146 | 7.660 | 314.289 | C17H14O6 | Kumatakenin | 0.0134 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 147 | 7.660 | 254.240 | C15H10O4 | 4′,7-Dihydroxyflavone | 0.0164 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 148 | 7.670 | 534.420 | C24H22O14 | Tricin 5-O-hexoside derivative | 0.0073 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 149 | 7.790 | 592.553 | C28H32O14 | Linarin | 0.0019 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 150 | 7.860 | 622.571 | C29H34O15 | Pectolinarin | 0.0015 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 151 | 7.879 | 594.520 | C30H26O13 | Tiliroside | 0.0020 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 152 | 7.971 | 416.000 | C21H20O9 | Apigenin 4-O-rhamnoside | 0.0002 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 153 | 7.999 | 288.252 | C15H12O6 | Eriodictyol | 0.3773 | Flavanones |

| 154 | 8.020 | 286.048 | C15H10O6 | 2′-Hydroxygenistein | 0.0155 | Isoflavonoids |

| 155 | 8.049 | 594.561 | C28H34O14 | Poncirin | 0.0011 | Flavanones |

| 156 | 8.050 | 302.043 | C15H10O7 | Morin | 1.3804 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 157 | 8.060 | 286.240 | C15H10O6 | Luteolin | 0.0010 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 158 | 8.100 | 668.600 | C33H32O15 | Tricin O-sinapoylpentoside | 0.0003 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 159 | 8.180 | 284.263 | C16H12O5 | Calycosin | 0.0329 | Isoflavonoids |

| 160 | 8.229 | 314.246 | C16H10O7 | Wedelolactone | 0.0004 | Isoflavonoids |

| 161 | 8.260 | 460.388 | C22H20O11 | Wogonoside | 0.0027 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 162 | 8.518 | 272.253 | C15H12O5 | Naringenin chalcone | 5.6733 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 163 | 8.519 | 500.840 | C21H21ClO12 | Myrtillin chloride | 0.0002 | Anthocyanins |

| 164 | 8.598 | 274.270 | C15H14O5 | Phloretin | 0.2532 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 165 | 8.610 | 272.069 | C15H12O5 | Butin | 4.9779 | Flavanones |

| 166 | 8.645 | 270.280 | C16H14O4 | Echinatin | 0.0001 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 167 | 8.683 | 272.250 | C15H12O5 | Naringenin | 5.7225 | Flavanones |

| 168 | 8.700 | 270.240 | C15H10O5 | Apigenin | 0.0057 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 169 | 8.720 | 270.240 | C15H10O5 | Genistein | 0.0002 | Isoflavonoids |

| 170 | 8.800 | 302.327 | C17H18O5 | Isomucronulatol | 0.0010 | Isoflavonoids |

| 171 | 8.811 | 286.240 | C15H10O6 | Kaempferol | 0.0106 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 172 | 8.849 | 300.263 | C16H12O6 | Tectorigenin | 0.0009 | Isoflavonoids |

| 173 | 8.860 | 302.079 | C16H14O6 | 7-O-Methyleriodictyol | 0.0017 | Flavanones |

| 174 | 8.911 | 300.260 | C16H12O6 | Diosmetin | 0.0031 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 175 | 8.960 | 302.236 | C15H10O7 | Quercetin | 0.0197 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 176 | 8.969 | 316.262 | C16H12O7 | Isorhamnetin | 0.0097 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 177 | 8.972 | 302.270 | C16H14O6 | Hesperetin | 0.0073 | Flavanones |

| 178 | 9.020 | 330.074 | C17H14O7 | 3,7-Di-O-methylquercetin | 0.0008 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 179 | 9.160 | 360.320 | C18H16O8 | 5,7,3′-trihydroxy-6,4′,5′-trimethoxyflavone | 0.0000 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 180 | 9.190 | 330.100 | C17H14O7 | Di-O-methylquercetin | 1.5690 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 181 | 9.370 | 372.375 | C20H20O7 | Isosinensetin | 0.0001 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 182 | 9.550 | 372.370 | C20H20O7 | Sinensetin | 0.0002 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 183 | 9.590 | 338.360 | C20H18O5 | Wighteone | 0.0004 | Isoflavonoids |

| 184 | 9.594 | 300.263 | C16H12O6 | Hydroxygenkwanin | 0.6367 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 185 | 9.870 | 284.263 | C16H12O5 | Maackiain | 0.0168 | Isoflavonoids |

| 186 | 9.935 | 300.310 | C17H16O5 | Farrerol | 0.0002 | Flavanones |

| 187 | 10.004 | 344.320 | C18H16O7 | Eupatilin | 0.0001 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 188 | 10.110 | 284.225 | C15H8O6 | Rhein | 0.0004 | Anthocyanins |

| 189 | 10.287 | 284.260 | C16H12O5 | Wogonin | 0.0014 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 190 | 10.315 | 286.279 | C16H14O5 | Isosakuranetin | 0.0023 | Flavanones |

| 191 | 10.340 | 374.347 | C19H18O8 | Chrysosplenetin B | 0.0001 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 192 | 10.372 | 256.250 | C15H12O4 | Pinocembrin | 0.0015 | Flavanones |

| 193 | 10.373 | 514.520 | C27H30O10 | Baohuoside I | 0.0004 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 194 | 10.374 | 374.341 | C19H18O8 | Casticin | 0.0005 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 195 | 10.400 | 286.328 | C17H18O4 | Loureirin A | 0.0010 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 196 | 10.518 | 402.390 | C21H22O8 | Nobiletin | 0.0046 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 197 | 10.520 | 356.332 | C19H16O7 | 6-Formyl-isoophiopogonanone A | 0.0022 | Flavanones |

| 198 | 10.550 | 284.263 | C16H12O5 | Oroxylin A | 0.0005 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 199 | 10.780 | 314.295 | C17H14O6 | Pectolinarigenin | 0.0002 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 200 | 11.410 | 372.370 | C20H20O7 | Tangeretin | 0.0030 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 201 | 11.419 | 336.720 | C16H13ClO6 | Peonidin chloride | 0.0007 | Anthocyanins |

| 202 | 11.520 | 388.368 | C20H20O8 | Demethylnobiletin | 0.0001 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 203 | 11.564 | 224.250 | C15H12O2 | Flavanone | 0.0007 | Flavanones |

| 204 | 11.740 | 298.295 | C17H14O5 | Mosloflavone | 0.0009 | Flavones and Flavanols |

| 205 | 11.930 | 324.370 | C20H20O4 | Isobavachalcone | 0.0005 | Chalcones and dihydrochalcones |

| 206 | 12.143 | 394.420 | C23H22O6 | Deguelin | 0.0001 | Isoflavonoids |

| 207 | 12.670 | 368.380 | C21H20O6 | Anhydroicaritin | 0.0000 | Flavones and Flavanols |

Dyskinesia Rehabilitation Effects of Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower in Zebrafish Larvae

Behavioral tests were performed on the zebrafish larvae at 6 dpf. As shown in Figure 2A, The black lines, green lines, and red lines indicate slow, medium, and fast movements, respectively. We found that the distance traveled by zebrafish in the AD model group was significantly shorter than the zebrafish in the untreated group, whether in light or dark environments (Figure 2B). The speed change of the zebrafish in the AD model group was also notably weakened after light stimulus alteration compared with the zebrafish in the untreated group (Figure 2C). These results indicated that AlCl3 lessened the locomotor capacity of the zebrafish, and this was consistent with the previous study (Pan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020). Accordingly, the establishment of zebrafish AD model was successful. After treatment with 4.0 μM donepezil, the distance traveled and speed change of the zebrafish both increased compared with the zebrafish in the AD group (Figures 2B,C). This implied that donepezil improved the dyskinesia of zebrafish induced by AlCl3. Interestingly, a similar trend of behavioral change in the positive group was also observed in the EUMF treatment groups. When the zebrafish were co-treated with AlCl3 and different concentrations of the EUMF (50, 100, and 200 μg/mL), their dyskinesias were also reduced. In particular, the EUMF treatment correlated with a longer distance in dark environments than that of the donepezil group (Figures 2B,C). The above results indicated that the EUMF improved the exercise capacity and may play a protective role against AlCl3-induced AD-like symptoms in zebrafish.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of EUMF on AlCl3-induced locomotion impairments in zebrafish. (A) Dgital track map. The red, green, and black lines depict fast, medium, and slow movements, respectively (n = 10). (B) Total distance moved in the Ctl, AlCl3, and AlCl3 + EUMF groups (***P < 0.001 vs. Ctl; ###P < 0.001 vs. AlCl3; n = 10). (C) Speed change in the Ctl, AlCl3, and AlCl3 + EUMF groups (the speed change after light stimulus is demarcated by the frame; n = 10).

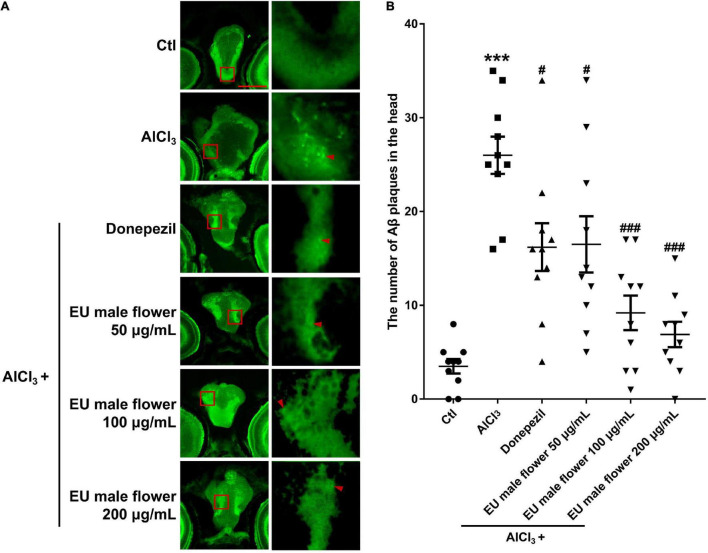

Inhibition the Amyloid β-Protein Aggregation Effects of Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower in the Zebrafish Larvae

Amyloid β-protein deposition is an important clinical hallmark in AD patients (Meldolesi, 2017). To further identify the anti-AD activity of the EUMF, the Aβ plaques in the heads of zebrafish were quantitatively determined. As shown in Figure 3, only a few of the Aβ plaques were observed in the brain of the untreated group. In contrast, there were many large Aβ plaques in the brain of the AD model group. Compared with the AD group, larval treatment with donepezil or EUMF (50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) significantly reduced the Aβ plaque count. These results implied that EUMF had anti-AD activity.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of EUMF on Aβ aggregation in zebrafish. (A) The Aβ plaques in the brain region were stained using thioflavin S in the Ctl, AlCl3, and AlCl3 + EUMF groups (Aβ is demarcated by arrows; scale bar = 100 μm). (B) Statistical analysis of the Aβ plaque count in each group (***P < 0.001 vs. Ctl; #P < 0.05; ###P < 0.001 vs. AlCl3; n = 10).

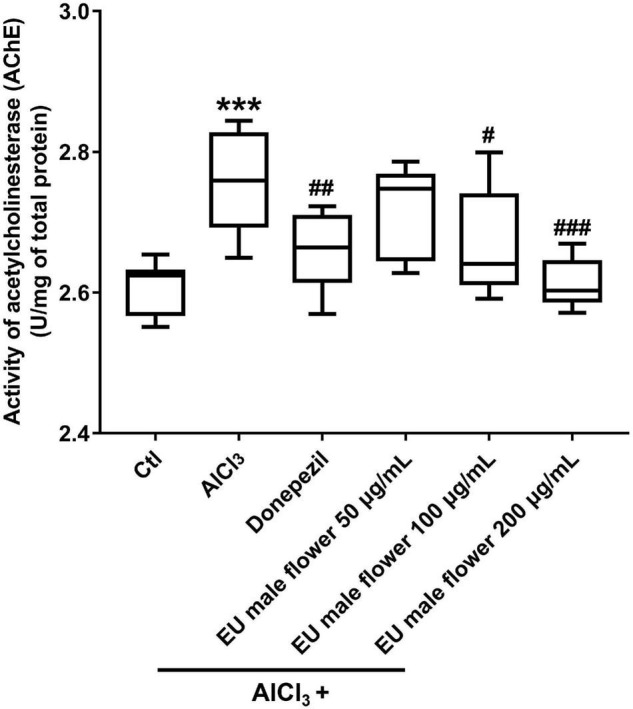

Inhibitory Activity of Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower on the Ache Activity

Ache is an enzyme that can degrade ACh. Many studies have proposed that a reduced level of ACh may be the primary etiology of AD. Hence, Ache has also been proposed to be related to the formation of AD (Remya et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2019). Based on this, we assessed the activity of Ache to explore the protective mechanism of EUMF on AD. As shown in Figure 4, the AD model group showed a higher activity of Ache compared with the untreated group. However, the groups co-treated with both AlCl3 and donepezil or different concentrations of EUMF showed reduced activity of Ache compared with the AD model group. Our results indicated that the EUMF may be an effective therapeutic agent for AD by suppressing the activity of Ache.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of EUMF on the AChE activity in zebrafish (***P < 0.001 vs. Ctl; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. AlCl3; n = 10).

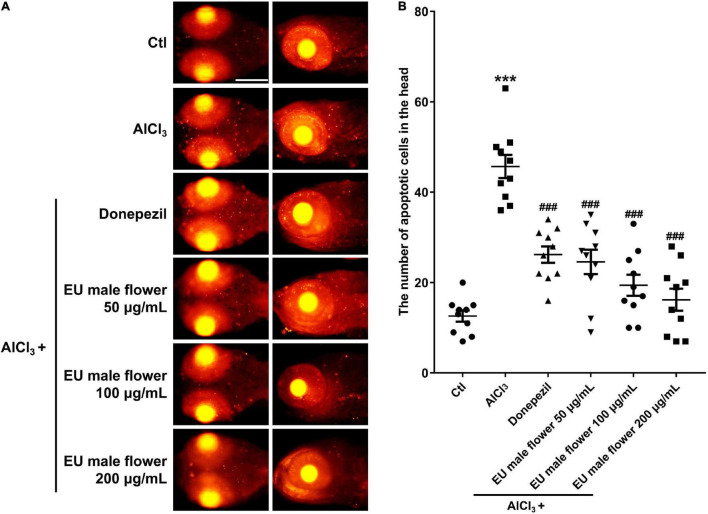

Effect of Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower on AlCl3-Induced Apoptosis in the Brain

We found many apoptotic cells that appeared primarily in the brain region in the zebrafish AD model. In contrast, no obvious apoptotic cells were observed in the control group. Donepezil or different concentrations of the EUMF treatment significantly reduced the number of apoptotic cells in the zebrafish brains (Figure 5). The above results suggested that EUMF suppressed the apoptosis induced by AlCl3 in zebrafish brain.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of EUMF on apoptosis in the brains of the AlCl3-modeled zebrafish. (A) The apoptotic cells were stained with TUNEL (scale bar = 100 μm). (B) Statistical analysis of the apoptotic cells count in the larvae heads (***P < 0.001 vs. Ctl; ###P < 0.001 vs. AlCl3; n = 10).

Effect of Eucommia ulmoides Olive Male Flower on the Expression of Autophagy-Related and Neurotransmitter-Related Genes

Many lines of evidence have suggested that dysregulated autophagy is implicated in a pathogenic role in the neurological diseases (Sheng et al., 2010; Chu, 2018). Therefore, we assayed the expression of autophagy-related genes to investigate whether EUMF protected against AD-like symptoms by regulating autophagy. Ambra1a, atg5, ulk1b, and lc3b are core members involved in autophagy (Kang et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2013). We found that transcript levels of aforementioned genes were significantly upregulated in the AD model group compared with the control, while when the EUMF reached a certain concentration, it reversed the increases (Figure 6). In addition, we also found that the EUMF treatment under a certain concentration downregulated the expression level of ache and slc6a3, and these were drastically increased after treatment with AlCl3 (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Transcriptional alterations of genes. The amount of gene expression was exhibited as the relative expression (shown as fold) compared with the Ctl. (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Ctl; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. AlCl3). (A–D) Expressions of genes involved in autophagy. (E) Transcript levels of ache. (F) Transcript levels of slc6a3.

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common clinical degenerative disease associated with aging. The complex pathogenetic factors of AD have limited its effective treatment. EUO is a traditional Chinese medicine. It has been reported that the extracts of EUO leaf can be used to treat AD. Therefore, we investigated the therapeutic effects of its male flowers on AD like symptoms using zebrafish. We found that the dyskinesia in the zebrafish AD model was significantly improved by EUMF. The Aβ plaques count, Ache activity, and number of apoptotic cells in the zebrafish AD model were also clearly reduced by EUMF. The above results indicated that the EUMF may be an agent for AD treatment. In addition, mechanism investigation revealed that the anti-AD activity of the EUMF may be related to its inhibition of excessive autophagy and abnormal expressions of ache and slc6a3 genes.

Autophagy is an important biological process by which cellular material is degraded by lysosomes or vacuoles and recycled. Paradoxically, it has the characteristics of a double-edged sword. Autophagy can serve to protect the nervous system by clearing degrading damaged organelles or accumulated misfolded proteins in neurons, but it may also induce neuron death and damage the nervous system (Shintani and Klionsky, 2004). Previous studies have shown that autophagy influences the secretion of Aβ to the extracellular space in neurons through either excretory or exocytic mechanisms, and hence it plays a critical role in Aβ plaque formation. Furthermore, extracellular Aβ plaques accumulation is an important pathogenic factor leading to AD (Nilsson et al., 2015). Based on these facts, we hypothesized that AlCl3 may activate abnormal excessive autophagy by upregulating the expression of ambra1a, atg5, ulk1b, and lc3b in zebrafish. Then further damage, referring to the deposition of extracellular Aβ plaques induced by abnormal excessive autophagy, would occur. Finally, AD-like symptoms in the zebrafish were induced. However, EUMF restored high expressions of ambra1a, atg5, ulk1b, and lc3b induced by AlCl3. Thus, autophagy was not excessively activated. Accordingly, this reduced the extracellular Aβ plaque count and reversed AD’s disease-like pathology in zebrafish.

Ache is the gene that encode Ache that inactivates the neurotransmitter ACh by catalyzing its hydrolysis to choline and acetic acid (Hu et al., 2019). Slc6a3 is the gene that encode the dopamine transporter (Dat) that can provide rapid clearance of dopamine (DA) (Dedic et al., 2018). The primary function of ACh is to complete the transmission of neural signals. Once the synthesis and decomposition of ACh is abnormal, neural signaling transition may be blocked. To some extent, AD will be the result (Hu et al., 2019). DA is also a neurotransmitter that is critically implicated in cognitive function. Previous studies have found that the restoration of DA transmission plays a role in learning and memory in the mouse model of AD. DA dysfunction has a pathogenic role in the cognitive decline symptoms of AD (Martorana and Koch, 2014). Because Ache and Dat are inhibitors of ACh and DA, respectively, it is conceivable that they also play a critical role in the occurrence of AD. Interestingly, our results showed that both the expressions of ache and slc6a3 genes were upregulated in the AD zebrafish model. However, treatment with EUMF reduced these increased expressions. Collectively, we suggest that beside of inhibiting the abnormal excessive autophagy, EUMF also reverse AD-like pathology in zebrafish by regulating the expressions of ache and slc6a3 at the transcript levels. Definitely, we will perform gene expression test of other neurotransmitters including glutamate in the future to further investigate the underlying mechanism.

Flavonoids are a group of plant metabolites which can improve the cognitive functions. They can work within the processes associated with AD (Kaur et al., 2022; Maccioni et al., 2022). For example, quercetin belonging to the subcategory of flavonoids can significantly mitigate memory deficits in scopolamine mice model via protection against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration (Olayinka et al., 2022). Eriodictyol which is a natural flavonoid compound can ameliorate cognitive dysfunction in APP/PS1 mice by inhibiting ferroptosis (Li L. et al., 2022). Anthocyanins can reduce the neuronal damage in in vivo and in vitro models of AD (Li H. et al., 2022). Here, we identified many flavonoids including quercetin-3′-O-glucoside, isoquercitrin, rutin hydrate, rutin, spiraeoside, isotrifoliin, isorhamnetin-3′-O-neohespeidoside, naringenin, naringenin chalcone, butin, myricitrin, isomucronulatol-7-O-glucoside, hyperoside, hesperetin 5-O-glucoside, narcissoside, di-O-methylquercetin, lonicerin, and morin in EUMF. Therefore, flavonoids in EUMF may contribute to its anti-AD effects. However, one limitation of this study is that the exact compounds of flavonoids in EUMF, which act as a promising agent against AD need further investigation. In the further work, we will analyze the composition and activity of the flavonoid compounds in EUMF to thoroughly understand the anti-AD activity of EUMF.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provided evidence that EUMF had anti-AD activity. EUMF ameliorated AD-like pathology in zebrafish possibly by inhibiting excessive autophagy and the abnormal expressions of ache and slc6a3. Flavonoid compounds in the EUMF may contribute to this biological process (Figure 7). Our data implied that EUMF is an attractive therapeutic candidate for AD.

FIGURE 7.

The proposed mechanism underlying the anti-AD effect of EUMF. EUMF inhibits the excessive autophagy and abnormal expressions of the ache and slc6a3 genes to exert the therapeutic effects against AD-like symptoms. Flavonoids in EUMF may contribute to this biological process.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committe of Biology Institute, Shandong Academy of Sciences.

Author Contributions

MJ conceptualized the idea and supervised the entire study. CS, SZ, SB, and JD performed the study and analyzed the results. MJ, QR, and YZ analyzed the results. CS and SZ wrote the manuscript. MJ and KL revised the manuscript and contributed to the final form. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding

This work was supported by the Belt and Road Innovative Foreign Experts Project (No. DL2021023004L), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42006090), and the Jinan Talent Project for Universities (Nos. 2021GXRC106, 2021GXRC111, and 2020GXRC031). We are also grateful for grants from Shandong High-end Foreign Experts Recruitment Program (Nos. WST2019006 and WST2020008), Key R&D Project of Shandong Province (No. 2021CXGC010507), and Science, Education, and Industry Integration Innovation Pilot Project of Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences) (No. 2020KJC-ZD10).

References

- Bakhtiari M., Panahi Y., Ameli J., Darvishi B. (2017). Protective effects of flavonoids against Alzheimer’s disease-related neural dysfunctions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 93 218–229. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao F., Jiang L., Zhang Y., Zhou C., Zhang L., Tang J., et al. (2018). Stereological investigation of the effects of treadmill running exercise on the hippocampal neurons in middle-aged APP/PS1 transgenic mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 63 689–703. 10.3233/JAD-171017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C. T. (2018). Autophagy in neurological diseases: an update. Neurobiol. Dis. 122 1–2. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedic N., Kühne C., Jakovcevski M., Hartmann J., Genewsky A. J., Gomes K. S., et al. (2018). Deussing, chronic CRH depletion from GABAergic, long-range projection neurons in the extended amygdala reduces dopamine release and increases anxiety. Nat. Neurosci. 21 803–807. 10.1038/s41593-018-0151-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S., Xiao Y., Lin Y., Mo Z. T., Chen Y. X., Peng F., et al. (2016). Chlorogenic acid-enriched extract from Eucommia ulmoides leaves inhibits hepatic lipid accumulation through regulation of cholesterol metabolism in HepG2 cells. Pharm. Biol. 54 251–259. 10.3109/13880209.2015.1029054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Wang J., Li M., Hao D., Yang Y., Zhang C. R., et al. (2014). Eucommia ulmoides Oliv.: ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 151 78–92. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Yu L., Tingting L., Lee H. J., Fang L., Wang Y., et al. (2020). A map of cis-regulatory elements and 3D genome structures in zebrafish. Nature 588 337–343. 10.1038/s41586-020-2962-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. H., Yang J., Zhang Y., Liu K. C., Liu T., Sun J., et al. (2019). Synthesis and biological evaluation of 3–(4-aminophenyl)-coumarin derivatives as potential anti-Alzheimer’s disease agents. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 34 1083–1092. 10.1080/14756366.2019.1615484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Li C., Shen Z., Zhu X., Xia B., Li C. (2016). Development of a zebrafish model for rapid drug screening against Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 4 174–185. 10.17265/2328-2150/2016.04.003 30171591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Mucke L. (2012). Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 48 1204–1222. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T. F., Zhang Y. J., Zhou H. Y., Wang H. M., Tian L. P., Liu J., et al. (2013). Curcumin ameliorates the neurodegenerative pathology in A53T alpha-synuclein cell model of Parkinson’s disease through the downregulation of mTOR/p70S6K signaling and the recovery of macroautophagy. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 8 356–369. 10.1007/s11481-012-9431-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang R., Zeh H. J., Lotze M. T., Tang D. (2011). The beclin1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 18 571–580. 10.1038/cdd.2010.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R., Sood A., Lang D. K., Bhatia S., Al-Harrasi A., Aleya L., et al. (2022). Potential of favonoids as anti-Alzheimer’s agents: bench to bedside. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 26063–26077. 10.1007/s11356-021-18165-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepp K. P. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease due to loss of function: a new synthesis of the available data. Prog. Neurobiol. 143 36–60. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstin H., Matthew D. C., Carlos T., Torrance J., Berthelot C., Muffato M., et al. (2013). The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496 498–503. 10.1038/nature12111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Hiroi T., Araki M., Hirokawa T., Miyazawa M., Aoki N., et al. (2012). Facilitative effects of Eucommia ulmoides on fatty acid oxidation in hypertriglyceridaemic rats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 92 358–365. 10.1002/jsfa.4586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zheng T. T., Lian F. Z., Xu T., Yin W. Y., Jiang Y. G. (2022). Anthocyanin-rich blueberry extracts and anthocyanin metabolite protocatechuic acid promote autophagy-lysosomal pathway and alleviate neurons damage in in vivo and in vitro models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrition 93:111473. 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Li W. J., Zheng X. R., Liu Q. L., Du Q., Jie Y., et al. (2022). Eriodictyol ameliorates cognitive dysfunction in APP/PS1 mice by inhibiting ferroptosis via vitamin D receptor-mediated Nrf2 activation. Mol. Med. 28 11–30. 10.1186/s10020-022-00442-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Qin J., Cheng Y., Ai Y., Han Z., Li M., et al. (2021). Polysaccharide from Patinopecten yessoensis skirt boosts immune response via modulation of gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids metabolism in mice. Foods 10:2478. 10.3390/foods10102478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Q., Chen Y., Fang J. Y., Jiang S. Q., Li P., Li F. (2020). Integrated network pharmacology and zebrafish model to investigate dualeffects components of Cistanche tubulosa for treating both osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 254:112764. 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L. F., Wu W. H., Zhou Y. J., Yan J., Yang G. P., Ouyang D. S. (2010). Antihypertensive effect of Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. extracts in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 129 238–243. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccioni R. B., Calfio C., Gonzalez A., Luttges V. (2022). Novel nutraceutical compounds in Alzheimer prevention. Biomolecules 12 249–264. 10.3390/biom12020249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorana A., Koch G. (2014). Is dopamine involved in Alzheimer’s disease? Front. Aging Neurosci. 6:252. 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldolesi J. (2017). Neurotrophin receptors in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 121 129–137. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves S., Macdonald A., Poole M., Dening K. H. (2021). “Participatory co-design: approaches to enable people living with challenging health conditions to participate in design research,” in Perspectives on Design and Digital Communication II. Springer Series in Design and Innovation, Vol. 14 eds Martins N., Brandão D., Moreira da Silva F. (Cham: Springer; ). 10.1177/14713012211065377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson P., Loganathan K., Sekiguchi M., Matsuba Y., Hui K., Tsubuki S., et al. (2015). Aβ secretion and plaque formation depend on autophagy. Cell Rep. 5 61–69. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.04234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu X. L., Xu D. R., Luo J., Kong L. Y. (2015). Main iridoid glycosides and HPLC/DAD-Q-TOF-MS/MS profile of glycosides from the antioxidant extract of Eucommia ulmoides Oliverse seeds. Indust. Crops Prod. 79 160–169. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.11.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noori T., Dehpour A. R., Sureda A., Sobarzo-Sanchez E., Shirooie S. (2021). Role of natural products for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 898:173974. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olayinka J., Eduviere A., Adeoluwa O., Fafure A., Adebanjo A., Ozolua R. (2022). Quercetin mitigates memory deficits in scopolamine mice model via protection against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Life Sci. 292:120326. 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H., Zhang J., Wang Y., Cui K., Cao Y., Wang L., et al. (2019). Linarin improves the dyskinesia recovery in Alzheimer’s disease zebrafish by inhibiting the acetylcholinesterase activity. Life Sci. 222 112–116. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson V. E. (2001). Galantamine: a new Alzheimer drug with a past life. Ann. Pharmacother. 35 1406–1413. 10.1345/aph.1A092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragya P., Arun U. (2021). Flavonoid-based nanomedicines in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics: promises made, a long way to go. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 4 74–95. 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remya C., Dileep K. V., Tintu I., Variyar E. J., Sadasivan C. (2012). Design of potent inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase using morin as the starting compound. Front. Life Sci. 6:107–117. 10.1080/21553769.2013.815137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remya C., Dileep K. V., Tintu I., Variyar E. J., Sadasivan C. (2013). In vitro inhibitory profile of NDGA against AChE and its in silico structural modifications based on ADME profile. J. Mol. Model. 19 1179–1194. 10.1007/s00894-012-1656-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remya C., Dileep K. V., Tintu I., Variyar E. J., Sadasivan C. (2014). Flavanone glycosides as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: computational and experimental evidence. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 76 567–570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria-Castro A., Alvarado-Echeverría I., Monge-Bonilla C. (2017). Molecular pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Ann. Neurosci. 4 46–54. 10.1159/000464422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng R., Zhang L. S., Han R., Liu X. Q., Gao B., Qin Z. H. (2010). Autophagy activation is associated with neuroprotection in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemic preconditioning. Autophagy 6 482–494. 10.4161/auto.6.4.11737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani T., Klionsky D. J. (2004). Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science 306 990–995. 10.1126/science.1099993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. K., Shi X. L., Donkor P. O., Ding L. Q., Qiu F. (2018). Megastigmane glycosides from leaves of Eucommia ulmoides oliver with ACE inhibitory activity. Fitoterapia 116 121–125. 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. S., Yu Z. P., Xia J. Y., Zhang X. M., Liu K. C., Attila S., et al. (2020). Anti-parkinson’s disease activity of phenolic acids from Eucommia ulmoides oliver leaf extracts and their autophagy activation mechanism. Food Funct. 11 1425–1440. 10.1039/c9fo02288k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. P., Fujikawa T., Mizuno K., Ishida T., Ooi K., Hirata T., et al. (2012). Eucommia leaf extract (ELE) prevents OVX-induced osteoporosis and obesity in rats. Am. J. Chin. Med. 40 735–752. 10.1142/S0192415X12500553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Zhang L., Yang C., Li Z., Rong S. (2019). Procyanidins and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 56 5556–5567. 10.1007/s12035-019-1469-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.