Abstract

An estimated 12.8 million pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infections have occurred within the United States as of March 1 2022, with multiple epidemic waves due to emergence of several SARS-CoV-2 variants. The aim of this study was to compare demographics, clinical presentation, and detected respiratory co-infections during COVID-19 waves to better understand changes in pediatric SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology over time.

A total of 4921 confirmed symptomatic pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positive patients identified during 3 waves (Nov 2020-Jan 2021, Jul to Oct 2021, Dec 2021-Jan 2022) were included. Significant changes in clinical symptoms were observed during the three COVID-19 waves with increased likelihood for fever (55.0% to 63.8%; p<0.001), congestion (46.6% to 52.1%; p=0.008), and cough (56.9% to 73.6%; p<0.001) and decreased prevalence for body/muscle aches (38.2% to 27.1%; p<0.001), loss of smell (10.2% to 2.0%; p<0.001) and loss of taste (11.2% to 2.1%; p<0.001).

Detection of co-infections differed significantly among COVID-19 waves, mostly related to the RSV outbreak in summer 2021 (lowest [0%] in Wave 1; highest [37.8%] in Wave 2 [p<0.001]). Rhinovirus/enterovirus and RSV were the most common detected co-infections with SARS-CoV-2.

Loss of taste/smell became less prevalent in our SARS-CoV-2 positive pediatric cohort with each subsequent COVID-19 wave, suggesting that taste/smell changes may be variant-dependent. The epidemiology and clinical presentation of pediatric COVID-19 infections evolved since the global pandemic onset, reflecting changes in the SARS-CoV-2 virus, increasing proportions of younger infected patients, clinician approaches to testing, and evolving social mitigation initiatives.

Introduction

An estimated 6.9 million U.S. pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infections occurred during the first 8 months of the pandemic. [1] As of March 1, 2022, nearly 80 million infections have been reported in the United States, [2] including 12.8 million cases among children. [3] The American Academy of Pediatrics has estimated that the rate of COVID infections among children is 16,000 cases per 100,000 children. [3] Among symptoms reported for pediatric COVID-19, fever and cough were most common, [4] although less often than in adults. [4, 5] Early in the pandemic, preliminary data suggested that adult SARS-CoV-2 patients frequently reported anosmia (loss of smell) and ageusia (loss of taste).[6], [7], [8] A meta-analysis of adults reported anosmia/hyposmia as significantly associated with SARS-CoV-2 infections. [9] In a recent study of 141 SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT)-positive adolescents, Kumar and colleagues found that 28.4% of patients reported olfactory or taste dysfunction. [10] Another study found that 15% of the 33 pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection included in their nested case-control study reported anosmia and/or ageusia. [11]

Multiple patient characteristics have been associated with hospitalization for SARS-CoV-2 infection, including patient age, underlying chronic conditions, and racial/ethnic categories.[12], [13], [14] While studies of adult patients reported 27-52% of SARS-CoV-2 suspected patients were hospitalized, [12, 13] there is less research to identify factors related to lower admission rates among pediatric COVID CoV-2 infected patients. Data are clear, however, that pediatric COVID-19 is less severe and requires hospitalization less frequently than adults.[15, 16]

SARS-CoV-2 mutations have resulted in several variants of concern, which ultimately produced multiple epidemic waves globally and in the United States. The US Alpha variant wave began approximately in autumn 2020; the US Delta variant wave began approximately July 2021.[17] In December 2021, the first US case of the Omicron variant infection was identified, shortly after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared it a variant of concern.[18] Since December 2021, over 28 million total cases have been reported. [2]

Our aim was to analyze data from children confirmed to have SARS-CoV-2 infection during testing per our hospital's testing criteria. We compared demographics and the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-positive children across three waves. We evaluated for presenting signs/symptom(s) that might be associated with pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection among those qualifying for testing. Additionally, the rates of SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with other respiratory pathogens were compared over time.

Materials and Methods

Sample and data collection

We initially identified all pediatric patients tested by SARS-CoV-2 NAAT during acute care visits (i.e., inpatient, emergency department (ED), urgent care (UC), or pediatric outpatient clinic) at Children's Mercy Kansas City (CM) between March 2020 and January 15, 2022; pre-procedural same-day-surgery screening and community-testing (post-exposure testing) were excluded, leaving only those patients who were considered symptomatic at the time of testing. SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid amplification tests (Hologic APTIMA SARS-CoV-2, Cepheid SARS-CoV-2, Argene SARS-CoV-2 and Quidel Lyra SARS- CoV-2 assay) approved by FDA through EUA mechanism were used for standard of care testing. NAAT-positive patients were eligible for inclusion. All provider notes on the history of present illness were extracted from the electronic health record. Natural language processing (NLP) of all provider notes was used to determine the presence/absence of select symptoms considered related to COVID-19 infection per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [19] The NLP algorithms were developed to also evaluate for negation terms (e.g., “denies”, “no”, “never”). This allows for distinguishing, for example, ‘patient reports cough’ from ‘patient denies cough’. Inpatient and observation patients (admitted for <24 hours) were considered ‘hospitalized’, while all other patient types (clinic, emergency department [ED], and urgent care [UC]) were considered outpatients. Sampled patients that had incomplete provider notes were excluded from the analysis. Three COVID waves were identified based on the SARS-CoV-2 test date: the first wave (“Wave 1”) seen at our institution, from Nov 2020-Jan 2021; the Delta wave (“Wave 2”), from Jul 2021-Oct 2021; and the Omicron wave (“Wave 3”), from Dec 2021-Jan 15 2022. NAAT-positive patients with a test date that occurred outside these pre-defined waves were excluded.

Concurrent SARS-CoV-2 NAAT and respiratory viral molecular tests

A subset of our SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-tested patients also underwent testing with the: 1) rapid molecular influenza test (Abbott ID NOW influenza A&B2); 2) rapid molecular respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) test (Abbott ID NOW RSV test); and/or 3) Respiratory Panel (RP) molecular-multiplex assay (Biofire LLC, Idaho). The decision to order these additional was per clinicians’ discretion. The RP multiplex PCR test is an FDA-cleared molecular respiratory panel assay that can detect 18 viruses and 4 bacteria. Hereafter we refer to these three respiratory tests as “concurrent respiratory” tests. Patients were included in this sub-analysis if the SARS-CoV-2 NAAT and any concurrent respiratory test occurred within 72 hours of each other. The rate of detected respiratory pathogens was compared across waves.

Data analysis

Demographic data and select presenting signs/symptoms, vital signs, and hospital admission were compared among the three COVID-19 waves. Patient age was assigned into 3 groups: 0-2 years (“pre-verbal”), 3-10 years (“pre-school & elementary”) and 11-18 (“middle and high school”). As a measure of underlying conditions, ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes were used to determine whether the patient had a complex chronic conditions (CCC) using the Feudtner classification scheme.[20] Presenting symptoms were also compared among age groups. Among children undergoing both SARS-CoV-2 NAAT and concurrent respiratory testing, the proportion with a detected concurrent respiratory pathogen was compared among COVID waves. For this analysis, a positive RP multiplex assay was defined as identification of any of rhinovirus/enterovirus, RSV, parainfluenza, adenovirus, or seasonal coronaviruses; while the RP panel did test for the presence of other respiratory pathogens (e.g., Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Bordetella pertussis), none were detected among our subset of patients concurrently tested for SARS-CoV-2 during the study time period. Trends in select lab-confirmed respiratory infections from our entire institution are provided to describe fluctuation patterns relative to our COVID waves.

Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used for categorical comparisons. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparing inpatient hospital length of stay and patient vital signs (i.e., respiratory rate, maximum temperature, and percent oxygen saturation. Multivariable, multinomial regression models, stratified by age group, were used to compare the odds of infection within a COVID wave, with Wave 1 used as the referent group. Included fixed effects were select symptoms, race/ethnicity, and CCC status. R software (v4.0.3; Vienna, Austria) was used for NLP. SAS software was used for all analyses (v9.4; Cary, NC). This study was reviewed and approved by CM's IRB, including the determination that informed consent was not needed.

Results

Population

A total of 4999 SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-positive patients, tested within Waves 1-3, were included in the initial sample. Of these, 78 (1.6%) were excluded since the provider notes were incomplete. Among the remaining analyzed patients (N=4921), 955 (19.4%) were from Nov 2020-Jan 2021 (Wave 1), 1388 (28.2%) were from Jul to Oct 2021 (Wave 2), and 2578 (52.4%) were from Dec 2021-Jan 2022 (Wave 3). Overall, 168 (3.4%) were hospitalized and 4753 (96.6%) were outpatients (2326 in ED, 2248 in UC, and 179 in clinics).

Demographics by COVID-19 Wave

Patients aged 3-10 years old represented 36.9% of all eligible patients, and this proportion varied little among the three waves (p=0.24) [Table 1 ]. However, the proportion of patients 0-2 and 11-18 years old changed significantly (p<0.001). The frequency of African American patients increased significantly from Wave 1 to Wave 2 (20.6% vs. 34.7%); the pediatric proportion of African Americans in the Kansas City metropolitan area is 13.5% [source: 2019 American Community Survey; www.ipums.org]. The prevalence of patients with a CCC did not vary significantly among waves.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics in Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-Positive Patients Presenting for Acute Care (N=4921), by COVID-19 Wave.

| Wave 1 (Nov 20-Jan 21) [N=955] | Wave 2 (Jul 21-Oct 21) [N=1388] | Wave 3 (Dec 21-Jan 15, 2022) [N=2578] | p-value | |

| Age – freq. (col %) | ||||

| Age 0-2 | 240 (25.1%) | 472 (34.0%) | 921 (35.7%) | <0.001 |

| Age 3-10 | 331 (34.7%) | 528 (38.0%) | 955 (37.0%) | 0.240 |

| Age 11-18 | 384 (40.2%) | 388 (27.9%) | 702 (27.2%) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 466 (48.8%) | 672 (48.4%) | 1263 (49.0%) | 0.942 |

| Male | 489 (51.2%) | 716 (51.6%) | 1315 (51.0%) | 0.942 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 264 (27.6%) | 279 (20.1%) | 634 (24.6%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 197 (20.6%) | 482 (34.7%) | 697 (27.0%) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 20 (2.1%) | 23 (1.7%) | 75 (2.9%) | 0.039 |

| White | 395 (41.4%) | 486 (35.0%) | 904 (35.1%) | <0.001 |

| Other | 68 (7.1%) | 95 (6.8%) | 191 (7.4%) | 0.803 |

| Unknown | 11 (1.1%) | 23 (1.7%) | 77 (3.0%) | 0.001 |

| Encounter type | ||||

| Admitted | 44 (4.6%) | 60 (4.3%) | 64 (2.5%) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient | 911 (95.4%) | 1328 (95.7%) | 2514 (97.5%) | <0.001 |

| Complex chronic conditions | ||||

| No | 813 (85.1%) | 1178 (84.9%) | 2244 (87.2%) | 0.082 |

| Yes | 142 (14.9%) | 210 (15.1%) | 330 (12.8%) | 0.082 |

Clinical Characteristics by COVID-19 Wave

As shown in Table 2 , significant changes in clinical symptoms were observed among COVID-19 waves. In subsequent COVID-19 waves increased prevalence occurred for fever (55.0% to 63.8%; p<0.001), congestion (46.6% to 52.1%; p=0.008), and cough (56.9% to 73.6%; p<0.001). Conversely, decreased prevalence was noted for body/muscle aches (38.2% to 27.1%; p<0.001), loss of smell (10.2% to 2.0%; p<0.001) and loss of taste (11.2% to 2.1%; p<0.001). The median length of stay (LOS) for hospitalized SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-positive declined significantly from Wave 1 (142 hours [interquartile range (IQR): 36, 458]) to Wave 2 (84 hours [IQR: 47, 193]) to Wave 3 (50 hours [IQR: 34, 121]; p=0.04). The median respiratory rate differed from Wave 1 (24 [IQR: 20, 32] to Wave 2 (28 [IQR: 22, 36] to Wave 3 (26 [IQR: 20, 36], with a p-value <0.001. Patient temperature and SpO2 were similar among waves.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics in Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-Positive Patients Presenting for Acute Care (N=4921), by COVID-19 Wave.

| Wave 1 (Nov 20-Jan 21) [N=955] | Wave 2 (Jul 21-Oct 21) [N=1388] | Wave 3 (Dec 21-Jan 15, 2022) [N=2578] | p-value | |

| Current/recent symptom reported – freq. (col %) | ||||

| Sore throat | 242 (25.3%) | 276 (19.9%) | 613 (23.8%) | 0.003 |

| Body/muscle aches | 365 (38.2%) | 415 (29.9%) | 698 (27.1%) | <0.001 |

| Fever | 525 (55.0%) | 915 (65.9%) | 1646 (63.8%) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty breathing | 137 (14.4%) | 220 (15.9%) | 335 (13.0%) | 0.046 |

| Congestion | 445 (46.6%) | 677 (48.8%) | 1343 (52.1%) | 0.008 |

| Cough | 543 (56.9%) | 956 (68.9%) | 1897 (73.6%) | <0.001 |

| Runny nose | 234 (24.5%) | 313 (22.5%) | 625 (24.2%) | 0.420 |

| Diarrhea | 89 (9.3%) | 131 (9.4%) | 190 (7.4%) | 0.038 |

| Vomiting | 91 (9.5%) | 179 (12.9%) | 309 (12.0%) | 0.040 |

| Headache | 292 (30.6%) | 327 (23.6%) | 525 (20.4%) | <0.001 |

| Loss of smell | 97 (10.2%) | 75 (5.4%) | 52 (2.0%) | <0.001 |

| Loss of taste | 107 (11.2%) | 87 (6.3%) | 55 (2.1%) | <0.001 |

Clinical Characteristics by Age Group

When comparing presenting symptoms based on patient age, several significant differences were observed, including body/muscle aches, fever, and loss of taste/smell (Table 3 ). Cough was the most common symptom reported for all three groups. Despite having a low p-value (p=0.03), the differences in proportions treated as outpatients, possibly a surrogate for milder disease, was not clinically meaningful (range 95.7% to 98.0%).

Table 3.

Relationship between Patient Age and Clinical Characteristics in Pediatric SARS-CoV2 NAAT-Positive Patients from All Three Waves Presenting for Acute Care (N=4921).

| Age 0-2 [N=1633] | Age 3-10 [N=1814] | Age 11-18 [N=1474] | p-value | |

| Current/recent symptom reported | ||||

| Sore throat | 36 (2.2%) | 474 (26.1%) | 621 (42.1%) | <0.001 |

| Body/muscle aches | 48 (2.9%) | 627 (34.6%) | 803 (54.5%) | <0.001 |

| Fever | 1141 (69.9%) | 1181 (65.1%) | 764 (51.8%) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty breathing | 286 (17.5%) | 192 (10.6%) | 214 (14.5%) | <0.001 |

| Congestion | 1000 (61.2%) | 764 (42.1%) | 701 (47.6%) | <0.001 |

| Cough | 1229 (75.3%) | 1216 (67.0%) | 951 (64.5%) | <0.001 |

| Runny nose | 481 (29.5%) | 404 (22.3%) | 287 (19.5%) | <0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 171 (10.5%) | 132 (7.3%) | 107 (7.3%) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting | 214 (13.1%) | 239 (13.2%) | 126 (8.6%) | <0.001 |

| Headache | 17 (1.0%) | 486 (26.8%) | 641 (43.5%) | <0.001 |

| Loss of smell | 17 (1.0%) | 43 (2.4%) | 164 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| Loss of taste | 9 (0.6%) | 49 (2.7%) | 191 (13.0%) | <0.001 |

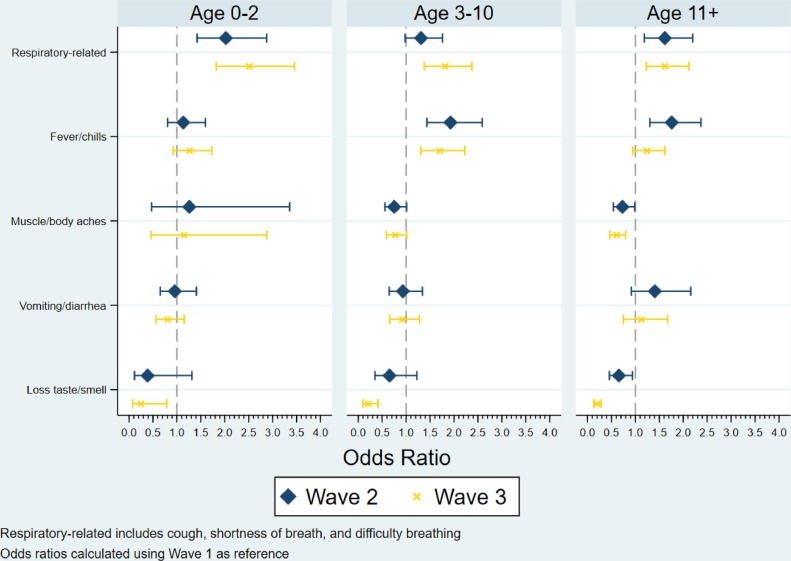

The adjusted odds of infection for Wave 2 and Wave 3 were both compared to Wave 1, stratified by age group (Fig. 1 ). Patients experiencing respiratory-related symptoms (i.e., cough, shortness of breath, and difficulty breathing) were more likely to be observed for Wave 2 and Wave 3, across all 3 age groups. Reporting loss of taste/smell was significantly less likely during Wave 3 for patients 3-10 years old (OR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.10, 0.42); p <0.001) and patients 11-18 years old (OR: 0.19; 95% CI: 0.13, 0.29; p<0.001). Vomiting and/or diarrheal symptoms were similar among waves, for all age groups.

Fig. 1.

Multivariable, Multinomial Model Predicting the Odds of Being in Wave 2 or Wave 3, relative to Wave 1, by Age Group. Note: regression models were adjusted for patient race/ethnicity and complex chronic condition status.

Concurrent Respiratory Co-infections

A total of 11220 children's samples underwent rapid influenza or rapid RSV antigen testing during the three COVID waves (Table 4 ). Of these, 1625 were SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-positive and received the rapid NAAT within 72 hours. Most detected co-infections were in Wave 2 and were RSV, 45 (21.5%).

Table 4.

Prevalence of Detected Concurrent Respiratory Co-Infections, by COVID-19 Wave.

| Wave 1 (Nov 20-Jan 21) | Wave 2 (Jul 21-Oct 21) | Wave 3 (Dec 21-Jan 15, 2022) | |||

| Total tested with rapid Flu/RSV NAAT and SARS-CoV-2 | 2 | 4165 | 5580 | ||

| COVID positive | 0 (0%) | 209 (5.0%) | 1416 (25.4%) | ||

| Rapid Flu A | 0 | 0 | 38 | ||

| Rapid Flu B | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| RSV | 0 | 45 | 7 | ||

| COVID negative | 2 (100%) | 3956 (95.0%) | 4164 (74.6%) | ||

| Rapid Flu A | 0 | 0 | 572 | ||

| Rapid Flu B | 0 | 0 | 8 | ||

| RSV | 0 | 1848 | 156 | ||

| Total tested with RP multiplex assay and SARS-CoV-2 | 413 | 849 | 262 | ||

| COVID positive | 40 (9.7%) | 37 (4.4%) | 29 (11.1%) | ||

| Adenovirus | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Coronavirus | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Metapneumovirus | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Parainfluenza | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Rhinovirus/enterovirus | 3 | 8 | 0 | ||

| RSV | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| COVID negative | 373 (90.3%) | 812 (95.6%) | 233 (88.9%) | ||

| Adenovirus | 10 | 21 | 9 | ||

| Coronavirus | 3 | 13 | 2 | ||

| Metapneumovirus | 0 | 4 | 15 | ||

| Parainfluenza | 0 | 61 | 8 | ||

| Rhinovirus/enterovirus | 137 | 311 | 37 | ||

| RSV | 0 | 201 | 11 |

A total of 3193 children's samples were tested with RP multiplex assay (Table 4). Of these, 110 samples were SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-positive and also underwent RP multiplex assay within 72 hours. Rhinovirus/enterovirus and RSV were the most common detected co-infections. The prevalence of detected co-infections was also highest in Wave 2: 7.0% in Wave 1, 37.8% in Wave 2, and 0% in Wave 3 (p<0.001). SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-positive patients with a co-infection had a higher prevalence of being hospitalized, compared with those that had no co-infection (11.1% vs. 4.6%; p=0.009). Hospitalized patients with a co-infection also had a significantly higher LOS (202 hours [IQR: 34, 374]) compared to no co-infected admitted patients (71 hours [IQR: 34, 345]), however this difference was not considered significant.

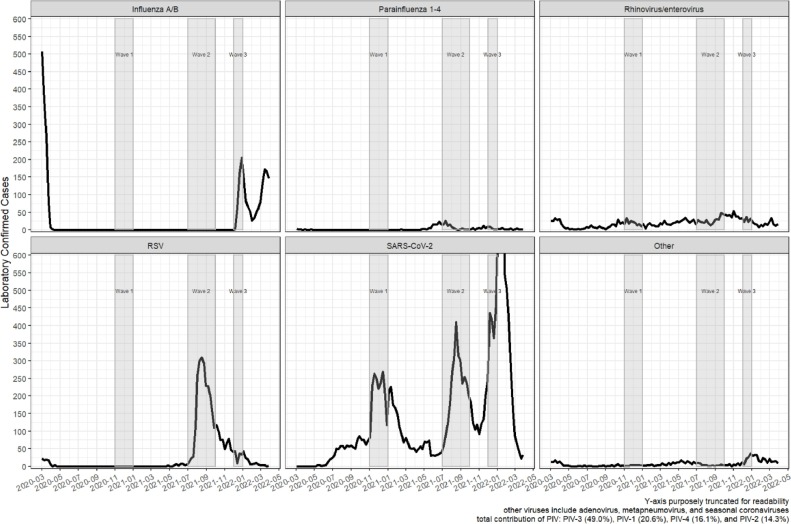

RSV season did not occur in 2020 and its timing was unusual in 2021, occurring in summer instead of winter-spring (Fig. 2 ). Influenza was also not detected during the customary winter season of 2020-2021, but then re-emerged for Wave 3. Rhinovirus, while detected in relatively low frequencies, was present through the entire COVID study period.

Fig. 2.

Institution-level Trends in Select Respiratory Pathogen Detections.

Discussion

Our study of nearly 5000 pediatric SARS-CoV-2 NAAT test-positive patients revealed multiple symptoms that varied from one COVID-19 wave to another, including cough, of fever, body/muscle aches, and loss of taste/smell. Notable age-dependent differences in presenting symptoms were also observed. In addition, co-infection with other respiratory pathogens differed significantly among COVID-19 waves, including a co-infection prevalence over 20% (37.8% for RP multiplex assay and 21.5% for RSV) during Wave 2 when RSV season occurred in the summer of 2021.

Early evidence had suggested anosmia/hyposmia could be an important indicator of SARS-CoV-2 infections among adults [6], [7], [8], [9], with prevalence between 22.7%-98.3% [9]. In this study, the prevalence of anosmia/ageusia in children during Wave 1 was slightly lower (13.1%) than the lower range reported for adults. However, this symptom was reported less frequently with each subsequent COVID-19 wave, from 13.1% down to 2.5%. Loss of taste/smell also differed significantly between those 3-10 years old (3.2%) vs. 11-18 years old (14.3%). Only 18 (1.1%) patients 0-2 years were classified as reporting loss of taste/smell, which makes sense because these are challenging to determine in preverbal children. As mentioned, significant decreases in the prevalence of loss of taste/smell are observed for all age groups in Wave 3. Future data could reveal whether taste/smell changes continue to evolve with newer variants.

In response to the escalating COVID-19 pandemic, social mitigations began in the United States beginning in March-April 2020. [21, 22] Over the 10 years prior to the pandemic, respiratory virus detections at our institution usually follow relatively predictable annual patterns, and peak times within each year (unpublished work; B. Lee). With the pandemic driven social mitigations, traditional viruses all but stopped circulating until mid-2021. [23] Despite early strict social mitigations, we still detected rhinovirus/enterovirus (HRV/EV) in our sub-sample of SARS-CoV-2 NAAT-positive RP multiplex assay-tested patients during Waves 1 and 2. Our Wave 2 co-infection rates occurred during the unexpected RSV re-emergence during summer 2021 (Wave 2) and influenza during Wave 3, seemingly due at least in part to removal/relaxation of social mitigation mandates. In our sub-cohort of SARS-CoV-2-positive pediatric patients that also had concurrent testing for other respiratory pathogens, we observed an overall co-infection rate of 6.3%. This rate is within the range noted in other studies that reported SARS-CoV-2 co-infection rates between 1.5%-20.7%. [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29] Among the 106 SARS-CoV-2-positive patients in our study who also had the RP multiplex assay completed, a co-detection occurred in 17 (16.0%) patients. A recent study by Mandelia and colleagues reported co-detections among non-SARS-CoV2 respiratory pathogens from a multiplex assay were highest for adenovirus (68.3%) while lowest for influenza B (10.0%).[30] Data from our study suggest that the rate of co-infections for SARS-CoV-2 infected patients might be somewhere in-between. SARS-CoV-2 co-infection studies are predominately adults or a combination of all ages. More research is needed to further understand precise SARS-CoV-2 co-infection rates in the pediatric populations.

Limitations include potential recall bias of reported symptoms by the parent/patient, and assuming that a symptom was absent if not detected in the chart. Second, NLP techniques can be susceptible to errors, leading to false detections. However, the developed algorithm had shown success in similar studies (>90% accuracy; unpublished, B. Lee) and it could be considered less subjective than manual review because the algorithm is applied consistently to every type of provider note. Third, this is a single-center study with patients that were predominately outpatients (96.6%), however other reports also indicate that pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infections are predominately mild and uncommonly require admission. Patients who had both COVID-19 NAAT and concurrent respiratory NAAT tests were only a subset of our analytic sample. It is possible that co-infection patterns would have differed if all patients had SARS-CoV-2 plus a concurrent multiplex PCR assay. Also, we chose to define the COVID-19 waves using CDC-defined variant determinations (e.g., ”Alpha”, “Delta”, “Omicron”). Genetic sequencing on all positive NAAT was not undertaken at our institution, therefore we cannot be certain of the predominance of each variant within each wave. Finally, we are not able to quantify effects on possible changes due to differences in availability or criteria for SARS-CoV-2 testing or in clinical decision approaches to ordering non-SARS-CoV-2 virus testing during each wave.

The epidemiology and clinical presentation of pediatric COVID-19 infections appeared to evolve since the global pandemic onset, seemingly affected by changes in the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, social mitigation initiatives, age proportions among tested patients, and seasonality of some co-infecting viruses.

Contributors Statement Page

Dr. Lee collaborated on the study design, collected data, performed the statistical analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the final manuscript.

Drs. Harrison, Myers, and Jackson critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Dr. Selvarangan collaborated on the study design, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report for the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and offer our thanks to all the Children's Mercy front-line staff and laboratory team that have done an amazing job caring for tens of thousands of suspected COVID-19 cases during the global pandemic.

References

- 1.Reese H., et al. Estimated incidence of COVID-19 illness and hospitalization - United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC, COVID Data Tracker. 2022.

- 3.Pediatrics, A.A.o. Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. 11/10/2021; Available from: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/.

- 4.Zimmermann P., Curtis N. COVID-19 in Children, Pregnancy and Neonates: A Review of Epidemiologic and Clinical Features. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(6):469–477. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castagnoli R., et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):882–889. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y., et al. Prevalence and Duration of Acute Loss of Smell or Taste in COVID-19 Patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(18):e174. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lechien J.R., et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(8):2251–2261. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng X., et al. COVID-19 and anosmia: A review based on up-to-date knowledge. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(5) doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hariyanto T.I., Rizki N.A., Kurniawan A. Anosmia/Hyposmia is a Good Predictor of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection: A Meta-Analysis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;25(1):e170–e174. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar L., et al. Loss of smell and taste in COVID-19 infection in adolescents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2021.110626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Concheiro-Guisan A., et al. Subtle olfactory dysfunction after SARS-CoV-2 virus infection in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;140 doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McPadden J., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes for 7,995 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrilli C.M., et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao J.Y., et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Hospitalized and Critically Ill Children and Adolescents with Coronavirus Disease 2019 at a Tertiary Care Medical Center in New York City. J Pediatr. 2020;223:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudan I., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic in children and young people during 2020-2021: A complex discussion on vaccination. J Glob Health. 2021;11:01011. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.01011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann P., Curtis N. Coronavirus Infections in Children Including COVID-19: An Overview of the Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention Options in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(5):355–368. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. Delta Variant. 2/11/ 2022; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html.

- 18.CDC. Omicron variant. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/omicron-variant.html. 2022.

- 19.CDC Symptoms of Coronavirus. 2022 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feudtner C., et al. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haffajee R.L., Mello M.M. Thinking Globally, Acting Locally - The U.S. Response to Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):e75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinders Folmer C.P., et al. Social distancing in America: Understanding long-term adherence to COVID-19 mitigation recommendations. PLoS One. 2021;16(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haddadin Z., et al. Acute Respiratory Illnesses in Children in the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: Prospective Multicenter Study. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-051462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swets M.C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenoviruses. Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1463–1464. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00383-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim D., et al. Rates of Co-infection Between SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2085–2086. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musuuza J.S., et al. Prevalence and outcomes of co-infection and superinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chekuri S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 coinfection with additional respiratory virus does not predict severe disease: a retrospective cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(Supplement_3):iii12–iii19. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burrel S., et al. Co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 with other respiratory viruses and performance of lower respiratory tract samples for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sreenath K., et al. Coinfections with Other Respiratory Pathogens among Patients with COVID-19. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00163-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandelia Y., et al. Dynamics and predisposition of respiratory viral co-infections in children and adults. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(4) doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.042. 631 e1-631 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]