Abstract

Objectives. To assess geographic differences in reaching national targets for viral suppression, homelessness, and HIV-related stigma among people with HIV and key factors associated with these targets.

Methods. We used data from the Medical Monitoring Project (2017–2020) and the National HIV Surveillance System (2019) to report estimates nationally and for 17 US jurisdictions.

Results. Viral suppression (range = 55.3%–74.7%) and estimates for homelessness (range = 3.6%–11.9%) and HIV-related stigma (range for median score = 27.5–34.4) varied widely by jurisdiction. No jurisdiction met any of the national 2025 targets, except for Puerto Rico, which exceeded the target for homelessness (3.6% vs 4.6%). Viral suppression and antiretroviral therapy dose adherence were lowest, and certain social determinants of health (i.e., housing instability, HIV-related stigma, and HIV health care discrimination) were highest in Midwestern states.

Conclusions. Jurisdictions have room for improvement in reaching the national 2025 targets for ending the HIV epidemic and in addressing other measures associated with adverse HIV outcomes—especially in the Midwest. Working with local partners will help jurisdictions determine a tailored approach for addressing barriers to meeting national targets. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(7):1059–1067. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306843)

Released in December 2021, the “National HIV/AIDS Strategy” (NHAS) outlines the plan for ending the HIV epidemic in the United States. The vision of NHAS is for the United States to

be a place where new HIV infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with HIV has high-quality care and treatment, lives free from stigma and discrimination, and can achieve their full potential for health and well-being across the life span.1

NHAS sets out to accomplish this vision through 4 key goals. Progress toward these goals is assessed through 9 national targets, 4 of which are used to assess progress in HIV care and treatment outcomes among people with diagnosed HIV, as well as known barriers to care and viral suppression—including stigma and homelessness. Using NHAS as a roadmap, the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative focuses its efforts in 57 of the jurisdictions with the highest burden of HIV.1,2

Viral suppression is critical for the health and well-being of people with HIV (PWH) and for reducing HIV incidence, which is the overarching goal of NHAS.1,3,4 However, several social determinants of health, including HIV-related stigma, discrimination, and housing instability, have been shown to affect outcomes across the HIV care continuum.5–7 These social determinants of health could deter PWH from even engaging in medical care in the first place.8 Social determinants of health are also associated with antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence and, thus, maintaining viral suppression.5–7 A large percentage of PWH experience multiple co-occurring social and medical conditions that could complicate HIV care and treatment.9 For instance, a large percentage of people who experience housing instability also report issues with depression and anxiety or substance use.6,7 NHAS recognizes the role of these social determinants of health in achieving HIV care continuum outcomes and prioritizes reducing HIV-related stigma and discrimination and health inequities that might drive disparities in HIV outcomes.1

Establishing baseline assessments of viral suppression, HIV stigma, and homelessness among PWH, as well as other measures associated with these national indicators, is vital to understanding potential gaps in local HIV prevention programs and could inform interventions for improving progress in meeting national targets. Although national baseline estimates have previously been established, estimates at the jurisdictional level have not previously been described to our knowledge. Also, baseline estimates have not been established for factors associated with these national indicators, including ART adherence, a strong determinant of viral suppression10; other forms of housing stability, often a precursor to homelessness7; and HIV health care discrimination, a form of enacted stigma that is associated with lower levels of HIV care engagement.11 Using national HIV surveillance data, we assessed geographic differences in reaching selected national HIV prevention targets related to viral suppression, homelessness, and HIV-related stigma among PWH, as well as key factors associated with these outcomes.

METHODS

We included data from 2 large national surveillance systems in our analysis: the National HIV Surveillance System (NHSS) and the Medical Monitoring Project (MMP). NHSS and MMP are conducted as a part of routine public health surveillance and are considered nonresearch.

NHSS collects demographic, clinical, and risk information on all adults and adolescents with diagnosed HIV infection in the United States. Data from NHSS are used to monitor national progress of several key national targets among persons with diagnosed HIV, including viral suppression1,12; for this study, we analyzed NHSS data reported for 2019.

MMP is a national surveillance system that collects annual, cross-sectional data to produce nationally and locally representative estimates of characteristics among adults with diagnosed HIV. Data from MMP are used to assess progress toward national targets for HIV-related stigma and homelessness. MMP also collects data on ART adherence, other forms of housing instability, and HIV health care discrimination.

MMP uses a 2-stage methodology to obtain a national probability sample of adults with diagnosed HIV. During the first stage, 16 US states and Puerto Rico were sampled from all US states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico with probabilities proportional to size based on AIDS prevalence at the end of 2002. These jurisdictions represented more than 70% of people with diagnosed HIV in the United States by the end of 2019,12,13 and 13 of the 16 states (81%) that report to MMP include high-burden jurisdictions that have been prioritized for intervention through the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States initiative.2,14 During the second MMP sampling stage, simple random samples of adults with diagnosed HIV were selected annually from each sampled jurisdiction from NHSS, a national census of all adults and adolescents with diagnosed HIV.

The sampled areas were California (including the separately funded jurisdictions of Los Angeles County and San Francisco), Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois (including Chicago), Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York (including New York City), North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania (including Philadelphia), Puerto Rico, Texas (including Houston), Virginia, and Washington State. The response rate was 100% at the first stage and ranged from 45% to 46% for the cycle years included in the analysis. More details on sampling methodology are described elsewhere.13

MMP data for the 2017–2019 cycles were collected during June of each cycle year through May of the following year. MMP staff conducted interviews of sampled participants to collect data on social determinants of health—including measures of housing instability, such as homelessness; HIV-related stigma; and discrimination experienced in the HIV care setting—and ART dose adherence. For this analysis, we report measures of homelessness and ART dose adherence based on 2017–2019 data cycles. Because of changes made to the MMP questionnaire after 2017, forms of unstable housing other than homelessness, HIV-related stigma, and HIV health care discrimination could be reported using only the 2018–2019 data cycles.

Measures

For this analysis, viral suppression data reported to NHSS in 2019 were reported nationally (i.e., among all states with complete laboratory reporting) and for the 16 states and 1 territory participating in MMP. We do not report data for jurisdictions with incomplete laboratory reporting, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Puerto Rico. For measures obtained from MMP data, we report weighted percentages and 95% confidence intervals. We report all measures nationally and by the 17 MMP reporting jurisdictions. We weighted MMP data to adjust for nonresponse and poststratified the data to known population totals by age, race/ethnicity, and sex at birth from NHSS.

Regarding NHSS measures, for all PWH who received an HIV diagnosis by the end of 2018 and were alive at the end of 2019, we defined viral suppression as the most recent viral load test during 2019 being less than 200 copies per milliliter or undetectable.

Regarding MMP measures, participants reported the number of missed ART doses during the 30 days before the interview, and we categorized ART dose adherence as missing 1 or more doses versus none.

We defined homelessness as living on the street, in a shelter, in a single-room–occupancy hotel, or in a car during the past 12 months. We defined other forms of unstable housing as being evicted, moving 2 or more times, or “doubling up” (defined as moving in with other people because of financial problems) in the past 12 months.

We assessed HIV-related stigma using a modified version of a 10-item Likert scale that Wright et al. developed and validated.15 We created a composite score ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating no stigma and 100 indicating the highest stigma.5,15 The scale encompassed 4 domains, including personalized stigma during the past 12 months, current disclosure concerns, current negative self-image, and current perceived public attitudes about PWH. We captured HIV health care discrimination experienced during the past 12 months through 7 Likert scale questions that we adapted based on a previously validated scale, in which participants were asked how often a health care provider discriminated against the patient through the health care provider’s actions in the HIV care setting.16 We categorized participants as experiencing HIV health care discrimination during the past 12 months if they answered rarely, about half the time, most of the time, or always (vs never) to any of the 7 health care discrimination questions.

Analytic Methods

For all measures included in the study, national and jurisdiction-level estimates were calculated. Of the measures included in this study, viral suppression at last test, homelessness, and HIV-related stigma are indicators assessed for progress toward meeting national targets in NHAS. For these measures, we compared national and jurisdiction-level estimates with the national targets to be achieved by 2025. In addition, we compared jurisdiction-level point estimates with the national estimate. The national target for viral suppression is 95%. For stigma, the national target is a 50% reduction in the 2018 national median score of 31.2 (15.6), and for homelessness, the national target is a 50% reduction in the 2017 national estimate of 9.1% (4.6%).1

We compared jurisdiction-level point estimates with the national estimate for ART dose adherence, other forms of unstable housing, and HIV health care discrimination; these are not national indicators but have been shown to be associated with the target outcomes.

We conducted all analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Nationally, 65.5% of people with diagnosed HIV were virally suppressed at last test (Figure 1). Viral suppression ranged from 53.9% (Mississippi) to 80.5% (Oregon); none of the reporting jurisdictions had reached the national target of 95% for 2025. Viral suppression was lowest in the Southern states Mississippi (53.9%) and Georgia (61.6%) and the Midwestern states Illinois (55.3%) and Indiana (60.2%).

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of People With Diagnosed HIV Who Were Virally Suppressed at Last Test, by Reporting Jurisdiction: National HIV Surveillance System, United States, 2019

Note. We defined viral suppression as the most recent viral load test in the past 12 months being undetectable or < 200 copies/mL. Viral suppression was reported in 2019 among adults and adolescents with diagnosed HIV who received an HIV diagnosis by the end of 2018 and were alive at the end of 2019, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National HIV Surveillance System. Results are not reported for New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Puerto Rico because of incomplete laboratory reporting. Data for Mississippi should be interpreted with caution because of incomplete ascertainment of deaths in 2019.

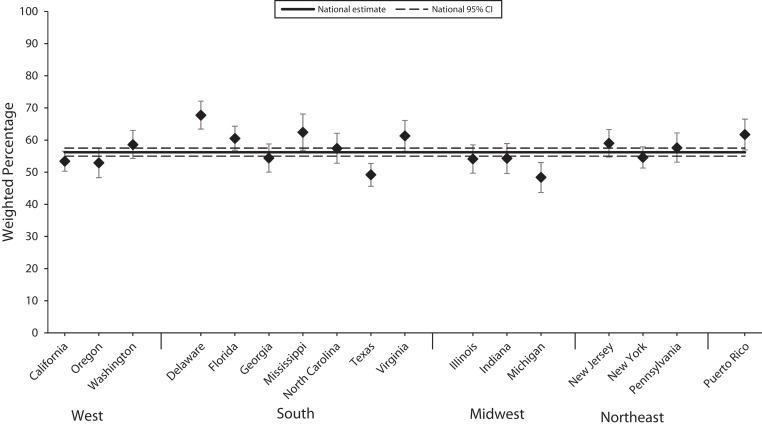

Nationally, 56.2% of adults with diagnosed HIV were ART adherent over the last 30 days—a critical step for viral suppression. Point estimates for ART dose adherence ranged from 48.4% (Michigan) to 67.7% (Delaware; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

ART Dose Adherence During the Past 30 Days Among Persons With Diagnosed HIV, by Reporting Jurisdiction: Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2017–2020

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy. We defined ART dose adherence as 100% adherence to ART doses during the past 30 days, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Medical Monitoring Project during the 2017–2019 data cycles.

Nationally, 9.3% of adults with diagnosed HIV experienced homelessness in the past 12 months; point estimates for homelessness ranged from 3.6% (Puerto Rico) to 12.4% (Michigan; Figure 3). Puerto Rico was the only jurisdiction for which the point estimate for homelessness reached the national target for homelessness of 4.6% among PWH in 2025.

FIGURE 3—

Percentage of Persons With Diagnosed HIV Who Experienced Homelessness in the Past 12 Months, by Reporting Jurisdiction: Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2017–2020

Note. We defined homelessness as living on the street, in a shelter, in a single-room–occupancy hotel, or in a car in the past 12 months, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Medical Monitoring Project during the 2017–2019 data cycles.

Overall, 17.5% experienced other forms of unstable housing during the past 12 months; point estimates of unstable housing ranged from 8.6% (Puerto Rico) to 25.2% (Indiana; Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). All 3 reporting jurisdictions in the Midwest (Illinois: 21.9%; Indiana: 25.2%; Michigan: 20.1%) had point estimates for other forms of unstable housing that were higher than the national estimate.

The national median score for HIV-related stigma was 30.9, and ranged from 27.5 (Washington State) to 34.4 (Michigan; Figure 4). None of the reporting jurisdictions reached the national target of 15.6 for HIV-related stigma. Several jurisdictions had median point estimates for stigma that were higher than the national estimate, including Texas (33.8) and Virginia (33.4) from the reporting jurisdictions in the South, all 3 reporting jurisdictions in the Midwest (Illinois: 33.1; Indiana: 32.3; Michigan: 34.4), Pennsylvania (31.9), and Puerto Rico (34.0).

FIGURE 4—

Median Scores in HIV-Related Stigma in the Past 12 Months Among Persons With Diagnosed HIV, by Reporting Jurisdiction: Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2018–2020

Note. We based HIV-related stigma on a 10-item scale ranging from 0 (no stigma) to 100 (high stigma) that measures 4 dimensions of HIV-related stigma during the past 12 months: personalized stigma during the past 12 months, current disclosure concerns, current negative self-image, and current perceived public attitudes about people living with HIV. Estimates were calculated based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Medical Monitoring Project during the 2018–2019 data cycles.

Nearly 1 in 4 (23.1%) adults with diagnosed HIV experienced HIV health care discrimination; point estimates ranged from 7.1% (Mississippi) to 29.8% (California; Figure B [available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org]). Point estimates for HIV health care discrimination were generally higher among reporting jurisdictions in the Midwest (Illinois: 28.1%; Indiana: 26.7%; Michigan: 29.6%).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use representative data to assess geographic differences in reaching national targets related to viral suppression, homelessness, and HIV-related stigma—and factors associated with these outcomes—used to assess progress toward reaching national HIV prevention and care goals. We demonstrated that HIV clinical outcomes and social determinants of health associated with adverse HIV clinical outcomes varied by jurisdiction. None of the reporting jurisdictions had achieved national 2025 targets for viral suppression or HIV stigma, and only 1 had achieved the national target for homelessness. Compared with national estimates, viral suppression was particularly low in many jurisdictions in the Midwest and the South.

In addition, ART dose adherence point estimates were low in all 3 jurisdictions included in the Midwest. Known barriers to ART adherence and viral suppression (e.g., housing instability, HIV-related stigma, and HIV health care discrimination) were most highly prevalent among reporting jurisdictions in the Midwest. The estimate for HIV-related stigma was high in Puerto Rico, and the estimate for HIV health care discrimination was high in California.

Patterns in national targets and factors associated with these targets, including HIV clinical outcomes and social determinants of health, varied substantially by state. Specifically, the percentage of PWH who were virally suppressed was lower than the national estimate (65.5%) in 4 of the 7 Southern states included in the analysis. Estimates of HIV stigma in all jurisdictions exceeded the national target, and estimates of homelessness in all but 1 jurisdiction exceeded the national target. Although levels of HIV-related stigma and homelessness were not above the national estimates for a majority of the Southern states included in the analysis, they were far above what is needed to meet the national targets for 2025. The included Midwestern states had low levels of viral suppression and high levels of other forms of unstable housing, HIV-related stigma, and HIV health care discrimination. Also, all 3 states included from the West had higher levels of viral suppression and lower levels of HIV-related stigma than the national estimates. However, levels of homelessness and HIV health care discrimination were higher than national estimates, particularly in California. Given that HIV stigma and homelessness are strongly associated with negative HIV outcomes,5,6 these findings underscore the importance of addressing these social determinants of health among PWH across the nation, including in areas disproportionately affected by HIV.

Even within states, progress in meeting targets for national indicators—and important factors associated with these indicators—could vary locally based on HIV burden, availability of HIV care resources, and HIV care and treatment funding allocation. Furthermore, barriers to HIV care and treatment are highly localized and depend on one’s environment and individual circumstances.17–19 Thus, each jurisdiction should work with its state and local partners to develop an approach that effectively addresses its own barriers to meeting the national targets.

There has been substantial progress in improving viral suppression among PWH nationwide, increasing from 43.4% in 2010 to 65.5% in 2019; however, there is much work to do to meet the national target of 95% by 2025.20,21 Ensuring that PWH are ART adherent and have their care needs met, regardless of their individual circumstances, is important for meeting the national target for viral suppression. ART adherence is a primary predictor of viral suppression, yet national estimates for ART adherence are suboptimal; moreover, social determinants of health affect ART adherence.10 Health is a universal basic need for all humans, but health inequities related to a variety of outcomes persist.22 Given that disparities in HIV care and treatment outcomes by social determinants of health exist, addressing needs of disproportionately affected populations is critical for meeting national targets related to HIV outcomes and is a national priority.1

Factors such as HIV-related stigma and discrimination are substantial barriers to health care quality and access, particularly among younger persons, women, transgender persons, and racial/ethnic minorities.5,23–26 In addition, PWH who experience HIV-related stigma and HIV health care discrimination may be more likely to experience symptoms of depression or anxiety.5,27 A multipronged, status-neutral approach that includes patient-, provider-, and community-level interventions could be useful in addressing stigma experienced among PWH, not just related to people’s HIV status but other factors as well, including racial/ethnic and gender identity. At the patient level, peer support groups that focus on discussing the negative effects of stigma and related coping mechanisms and that provide psychosocial support could be helpful. Social support is associated with positive mental health outcomes and ART adherence and may be particularly beneficial for those experiencing high levels of HIV-related stigma.28–30 Other interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, could help those with symptoms of depression or anxiety.31

At the provider level, provider training could focus on cultural and sexual health competency and include content on how to ascertain information on experienced stigma. This could be helpful in identifying and addressing stigma, as well as in understanding and addressing other challenges patients may be experiencing related to social determinants of health, such as unstable housing. Incorporating antistigmatizing, antidiscriminatory policies in health care settings can provide a safe space for HIV patients to seek care. However, such policy changes are only a first step in the needed shift in the cultural paradigm of embracing diversity and eradicating systemic racism and other forms of discrimination, such as that based on HIV status or gender identity. Finally, at the community level, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Let’s Stop HIV Together campaign could help increase awareness of HIV-related stigma and the role of all people in our community in stopping HIV-related stigma.32

PWH face a number of challenges related to difficult life circumstances, including housing instability. Nationally, almost 1 in 10 adults with diagnosed HIV have experienced homelessness,14 compared with less than 1% of all people in the United States,3,4 and nearly 1 in 5 experienced other forms of unstable housing over the past year.14 In addition, numerous HIV outbreaks across the United States have involved vulnerable populations, including unstably housed persons.33–36 Among adults with diagnosed HIV, homelessness disproportionately affects transgender persons, racial and ethnic minorities, people living at or below the poverty line, and people with a history of substance use, and homelessness is associated with adverse HIV clinical outcomes.6 Ryan White HIV/AIDS program–funded facilities offer critically important support services for PWH, such as housing assistance.37

The Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS program also offers critical housing assistance services to those in need. However, beneficiaries of Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS funds must be persons living at or below 80% of their area’s median income,38 potentially excluding some persons in need of services who are unstably housed. In fact, more than 1 in 6 adults with diagnosed HIV received housing assistance during the past year, but more than 1 in 10 people reported having an unmet need for these services.14 Given that other forms of housing instability could be a precursor to becoming homeless and are also associated with negative HIV clinical outcomes,7,39 expanding Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS funds and eligibility criteria could help address unmet needs related to housing assistance.

Housing status should also be assessed routinely at HIV care visits and through case managers and patient navigators so that referrals for housing assistance can be provided on the spot as needed. Expanding components of the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program’s comprehensive care model to other, non–Ryan White HIV/AIDS program–funded care settings, especially with regard to increasing access to patient navigation and case management services, could help in ensuring that all needs of PWH are met.

Limitations

This analysis has several limitations. First, we could not assess viral suppression using NHSS data for New Jersey, Pennsylvania, or Puerto Rico because of incomplete laboratory reporting. Also, data on viral suppression for Mississippi should be interpreted with caution because of incomplete ascertainment of deaths that occurred during 2019.

Second, ART dose adherence and social determinants of health assessed through MMP were based on self-report and are subject to misclassification. Although MMP response rates were suboptimal, we adjusted results for nonresponse and poststratified estimates to known population totals by age, race/ethnicity, and sex at birth from the NHSS using established, standard methodology.13 Assessment of state-level estimates in specific regions using MMP data should be interpreted with caution, as MMP data are not designed to provide regionally representative estimates. Because we included jurisdictional estimates for all measures in the calculation of the national estimates, we could not make statistical comparisons.

Finally, data from 2020 to 2021 were not included in this analysis, which could have influenced our findings because of worsening socioeconomic conditions and challenges in seeking HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic.39–41 However, these results still underscore the importance of monitoring national and local status in meeting national targets over time.

Public Health Implications

Our findings demonstrate that jurisdictions across the country have room for improvement in reaching the 2025 national targets for viral suppression and social determinants of health that are critical for achieving the goals of NHAS, including homelessness and HIV stigma. In addition, improving other factors associated with these national indicators—including ART adherence, other forms of housing instability, and HIV health care discrimination—could help in achieving these targets and meeting national prevention and care goals. Jurisdictions should work with their state and local partners to identify the distribution of social determinants of health among PWH, including the overlap of co-occurring social and medical conditions, in their local service areas. Doing so will help in developing a tailored approach that effectively addresses local barriers to meeting national targets that are vital for ending the HIV epidemic in the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for the Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) is provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

We acknowledge the local MMP staff, health departments, and participants, without whom this research would not have been possible.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The National HIV Surveillance System and MMP are conducted as part of routine public health surveillance and are considered nonresearch. For MMP, participating jurisdictions obtained institutional review board approval as needed; verbal or written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.White House. 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/National-HIV-AIDS-Strategy.pdf

- 2.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2016;316(2):171–181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beer L, Tie Y, McCree DH, et al. HIV stigma among a national probability sample of adults with diagnosed HIV—United States, 2018–2019. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(suppl 1):39–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03414-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wainwright JJ, Beer L, Tie Y, Fagan JL, Dean HD Medical Monitoring Project. Socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of persons living with HIV who experience homelessness in the United States, 2015–2016. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(6):1701–1708. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02704-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus R, Tie Y, Dasgupta S, et al. Characteristics of adults with diagnosed HIV who experienced housing instability: findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Medical Monitoring Project, United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2021 doi: 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dasgupta S, Tie Y, Beer L, Weiser J. Unmet needs for ancillary care services are associated with HIV clinical outcomes among adults with diagnosed HIV. AIDS Care. 2021 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2021.1946001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menza TW, Hixson LK, Lipira L, Drach L. Social determinants of health and care outcomes among people with HIV in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(7):ofab330. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson IB, Tie Y, Padilla M, Rogers WH, Beer L. Performance of a short, self-report adherence scale in a probability sample of persons using HIV antiretroviral therapy in the United States. AIDS. 2020;34(15):2239–2247. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brincks AM, Shiu-Yee K, Metsch LR, et al. Physician mistrust, medical system mistrust, and perceived discrimination: associations with HIV care engagement and viral load. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(10):2859–2869. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas 2019. May 2021https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf

- 13.Beer L, Johnson CH, Fagan JL, et al. A national behavioral and clinical surveillance system of adults with diagnosed HIV (the Medical Monitoring Project): protocol for an annual cross-sectional interview and medical record abstraction survey. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(11):e15453. doi: 10.2196/15453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-special-report-number-28.pdf

- 15.Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam P, Templin T, Frey M. Stigma scale revised: reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV+ youth. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(1):96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peek ME, Nunez-Smith M, Drum M, Lewis TT. Adapting the everyday discrimination scale to medical settings: reliability and validity testing in a sample of African American patients. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(4):502–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimmel AD, Masiano SP, Bono RS, et al. Structural barriers to comprehensive, coordinated HIV care: geographic accessibility in the US South. AIDS Care. 2018;30(11):1459–1468. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1476656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta S, Kramer MR, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, Reed L, Sullivan PS. The effect of commuting patterns on HIV care attendance among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Atlanta, Georgia. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015;1(2):e10. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson Lyons S, Gant Z, Jin C, Dailey A, Nwangwu-Ike N, Satcher Johnson A. A census tract–level examination of differences in social determinants of health among people with HIV, by race/ethnicity and geography, United States and Puerto Rico, 2017. Public Health Rep. 2022;137(2):278–290. doi: 10.1177/0033354921990373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-18-5.pdf

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data—United States and 6 Dependent Areas, 2019. May 2021https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-vol-26-no-2.pdf

- 22. Marmot M; Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehme AK, Moneyham L, McLeod J, et al. HIV-infected women’s relationships with their health care providers in the rural deep South: an exploratory study. Health Care Women Int. 2012;33(4):403–419. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2011.610533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:848. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sweeney SM, Vanable PA. The association of HIV-related stigma to HIV medication adherence: a systematic review and synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):29–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baugher AR, Beer L, Fagan JL, et al. Prevalence of internalized HIV-related stigma among HIV-infected adults in care, United States, 2011–2013. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(9):2600–2608. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1712-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams R, Cook R, Brumback B, et al. The relationship between individual characteristics and HIV-related stigma in adults living with HIV: medical monitoring project, Florida, 2015–2016. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):723. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08891-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Servellen G, Lombardi E. Supportive relationships and medication adherence in HIV-infected, low-income Latinos. West J Nurs Res. 2005;27(8):1023–1039. doi: 10.1177/0193945905279446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam PK, Naar-King S, Wright K. Social support and disclosure as predictors of mental health in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(1):20–29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turan B, Smith W, Cohen MH, et al. Mechanisms for the negative effects of internalized HIV-related stigma on antiretroviral therapy adherence in women: the mediating roles of social isolation and depression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(2):198–205. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma PHX, Chan ZCY, Loke AY. Self-stigma reduction interventions for people living with HIV/AIDS and their families: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):707–741. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Let’s stop HIV together: HIV stigma. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/stophivtogether/hiv-stigma/index.html

- 33.US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2018. https://www.wpr.org/sites/default/files/2018-ahar-part-1-compressed.pdf

- 34.Alpren C, Dawson EL, John B, et al. Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: an outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs—Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(1):37–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dasgupta S, Broz D, Tanner M, et al. Changes in reported injection behaviors following the public health response to an HIV outbreak among people who inject drugs: Indiana, 2016. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(12):3257–3266. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02600-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among heterosexual persons who are living homeless and inject drugs—Seattle, Washington, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(15):344–349. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Health Resources and Services Administration. 2022. https://ryanwhite.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ryanwhite/grants/service-category-pcn-16-02-final.pdf

- 38.US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2022. https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/hopwa/hopwa-eligibility-requirements

- 39.Dawson L, Kates J.2020. https://www.kff.org/hivaids/issue-brief/delivering-hiv-care-prevention-in-the-covid-era-a-national-survey-of-ryan-white-providers

- 40.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and

- 41.Beer L, Tie Y, Dasgupta S, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and unemployment, subsistence needs and mental health among adults with HIV in the United States. AIDS. 2022;36(5):739–744. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000003142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]