The mission of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is “to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability,” primarily via biomedical research.1 The current moment, including the COVID-19 pandemic, renewed reckoning with systemic racism, political division, massive wealth inequality, the opioid crisis, rising rates of mental illness, and climate change, highlights the importance of biomedical research and the need for other approaches also. Thus, we ask the question: is it time to restructure the NIH? We explore reasons for and against restructuring and offer next steps.

WHY RESTRUCTURE?

Beyond prior arguments (e.g., organizing around outcomes is problematic),2–6 a key reason to restructure NIH is to reduce epistemic exclusion. Epistemic exclusion involves the underrepresentation of people and research methods that are relevant to a topic.7 Guided by principles of trustworthy scientific consensus,8 epistemic exclusion involves scientific practices that reduce diversity of relevant perspectives and methods by systematically favoring some perspectives or methods over others through resource allocation or consensus generation practices. This favoring is based on unexamined historical precedents, not the merits of one perspective or method over another. Epistemic exclusion reduces the trustworthiness of scientific consensus; thus, reducing it is critical for science.

Evidence suggests epistemic exclusion occurs within the NIH related to race and discipline. Evidence suggests system biases in (1) scoring favoring White over Black researchers,9 (2) less funding for topics Black researchers focus on,10 and (3) underrepresentation of Black researchers in study sections.10 Hoppe et al. stated, “[T]he funding gap between African American/Black and White scientists may be driven by a vicious cycle, beginning with African American/Black investigators’ preference . . . for topics less likely to excite . . . the scientific community, leading to a lower probability of award, which in turn limits resources and decreases . . . funding in the future.”10(p8) This vicious cycle is epistemic exclusion. Although evidence exists for Black researchers, epistemic exclusion likely occurs with other social and ethnic groups, though more research is needed.

With regard to disciplines, approximately 70% of variance in health is attributable to nonbiological determinants, such as behaviors, social circumstances, and environmental factors.11 Thus, producing trustworthy scientific knowledge relevant to the NIH mission requires a diversity of disciplines receiving equitable funding (e.g., biology, medicine, nursing, physiology, public health, psychology, history, sociology, law, ethnic studies, neuroscience, political science, economics, ecology, urban planning, engineering, systems science), but equitable funding is not occurring. In 2019,12 approximately 22% of the NIH’s extramural budget ($6 billion out of $29 billion) went to social and behavioral research, and approximately 8% went toward environmental (e.g., impact of climate change) research; the rest was biomedical research. Although biomedical research acknowledges social, behavioral, and environmental determinants, it uses its methodological assumptions, which are not always appropriate for nonbiological phenomena.11 Thus, determinants explaining approximately 70% of health variance receive approximately 30% of funding within the NIH. Although equitable funding need not be equal funding, this mismatch suggests disciplinary epistemic exclusion within the NIH, as does NIH’s self-identification as the biomedical research enterprise.13

In line with the visions of the National Institutes for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD)14,15 and the NIH UNITE initiative,13 reducing epistemic exclusion is important for reducing health disparities, ending structural racism, and advancing a more equitable scientific workforce. Reducing epistemic exclusion, particularly disciplinary epistemic exclusion, would also increase the types of evidence-based approaches studied.11 From this evidence base, it is likely that a more diverse repertoire of evidence-based solutions across determinants would be produced, thus enabling NIH to better achieve its mission.11 NIH’s practices are often used as a template for other funding agencies, such as when other funders (e.g., the California Initiative for the Advancement of Precision Medicine) use NIH review procedures. Therefore, NIH practices that propagate epistemic exclusion will likely permeate elsewhere. Thus, NIH needs to lead on reducing epistemic exclusion related to race, discipline, and beyond. This is true even if, after examination, NIH is not restructured.

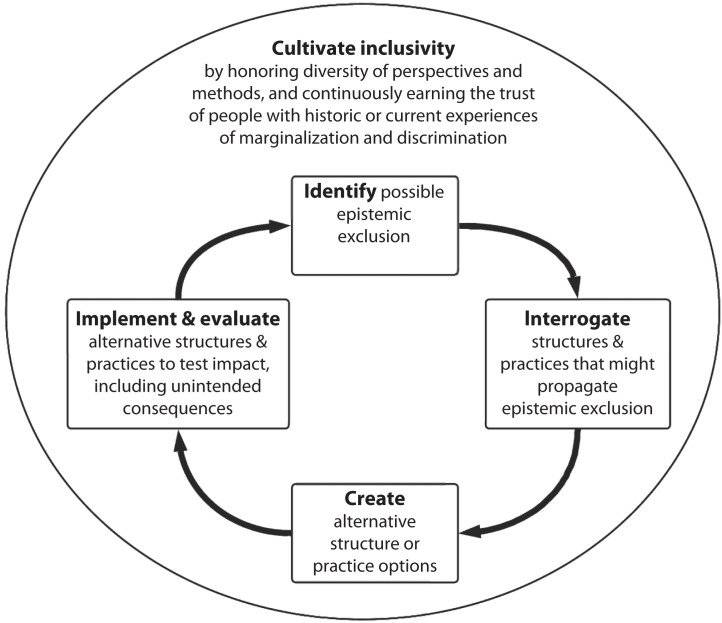

Reducing epistemic exclusion, whether it occurs related to race, discipline, or something else, should be studied scientifically, such as the process in Figure 1. First, identify possible epistemic exclusion. Second, interrogate structures and practices for possible propagation of epistemic exclusion. For NIH, these structures include but are not limited to institutes, organizational charts, staffing, decision-making practices, and external institutions with a history of NIH funding; practices include methods for ruling out alternatives, strategies for cultivating synthesis or consensus, precedents, social norms, rules of engagement, and default actions. Third, propose new structure and practice options, which could be developed and vetted by diverse stakeholders. Last, implement and test new options to determine the impact on epistemic exclusion, improved health outcomes, and unintended consequences.

FIGURE 1—

A Proposed Process for Cultivating Inclusivity in Health Sciences

Although more speculative, this approach could be useful for increasing public confidence in science. A 2019 Pew Research Center survey found a large minority, 35%, stating that science produces “any result a researcher wants.”16 Although improving scientific rigor and communication are possible solutions, another involves including dissenting perspectives and methods in discourse. This will not work with everyone, particularly those incentivized to stoke dissent, but improving inclusiveness would likely increase understanding of science and thus trust.

REASONS NOT TO RESTRUCTURE

There are several reasons not to restructure. First, the NIH has a long track record of success in biomedical research (e.g., COVID-19 vaccinations and therapeutics). Although NIH structures and practices may produce epistemic exclusion, restructuring could have the unintended consequence of reducing biomedical research quality. Second, the NIH receives bipartisan support, which could be jeopardized if restructured. Third, the NIH already includes mechanisms of restructuring, as evidenced by (1) the formation of the NIMHD,14,15 which provides pathways for historically marginalized groups and methods to be incorporated within the NIH; (2) the UNITE initiative to end structural racism13; (3) study section composition changes that sought to expand disciplinary representation; and (4) NIH embracing open science practices, including citizen science. Fourth, it is plausible (though we think unlikely) that epistemic exclusion does not happen across funders. Last, new structures and practices might shift but not reduce epistemic exclusion.

HOW TO PROCEED

There are good reasons for and against restructuring the NIH. We suggest two complementary next steps. First, both NIMHD and UNITE should incorporate—or continue its use if they are already doing so—the process shown in Figure 1. For example, they could monitor epistemic exclusion within NIH (e.g., study sections, review processes) and, when identified related to race, ethnicity, or otherwise, study solutions. Although this is an excellent start, this would not be sufficient to address disciplinary epistemic exclusion. Furthermore, the complexities and likelihood of unintended negative consequences from both action and inaction suggest the need for a broader, thorough, inclusive, and ongoing effort.

A neutral forum is needed whereby active NIH stakeholders and people with historic or current experiences of marginalization and/or discrimination can come together, like the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. An outside group could facilitate the process with robust community organizing for (1) working through implicit and explicit power differentials and rules of engagement that favor one perspective or method over another based only on historical precedent and not well-articulated merit; (2) cultivating trust through relationships and compassion, not merely reason and empiricism; and (3) creating an inclusive leadership model that includes (a) active NIH stakeholders; (b) people from historically marginalized groups, including Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, with expertise in advancing justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (e.g., see Akom17); (c) historically underrepresented disciplines, such as sociology, ethnic studies, and others listed earlier; and (d) constituents who do not trust science while also lacking a conflict of interest (e.g., people with well-intentioned antivaccination perspectives). Within this forum, the work would need to progress at the pace of trust—meaning slow when trust is low and fast when it is present—with funding to support ongoing trust cultivation.

Guided by the NIH mission, the group could follow the process in Figure 1, including identifying possible epistemic exclusion, interrogating NIH practices that may propagate epistemic exclusion, creating new possible practices that could feasibly reduce epistemic exclusion, and then implementing and evaluating new options. For this last step, it will be important to differentiate uncontested from contested solutions, such that uncontested solutions can be implemented and contested ones can be tested in a way that diverse stakeholders agree is fair. For example, multiple options of new institute structures could be produced by diverse workgroups (e.g., see Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, or Crow18), which could then be vetted. The NIH could repeat the process every 5 to 10 years to further demonstrate its commitment to reducing epistemic exclusion and, feasibly, improve public scientific literacy.

CONCLUSION

Health research in the United States could benefit from, first, NIMHD and the UNITE initiative implementing an ongoing process for identifying and addressing epistemic exclusion, and, second, NIH engaging in an extensive, inclusive, deliberative, on-going process focused on addressing epistemic exclusion. This process would be beneficial even if, after reflection, the NIH is not radically restructured. If the NIH meaningfully invests in such a process, it could model a process of respectful inclusion and healing that could reduce structural inequities and foster the type of deliberative process science and society desperately need to advance equity and justice for all.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

E. Hekler, C. A. M. Anderson, and L. A. Cooper have all received funding from the National Institutes of Health. E. Hekler, C. A. M. Anderson, and L. A. Cooper do not have additional conflicts of interests or disclosures.

See also Hyder, p. 969.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institutes of Health. Mission and Goals. Available. 2020. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/mission-goals

- 2.Ioannidis JP. Meta-research: why research on research matters. PLoS Biol. 2018;16(3):e2005468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ioannidis JP, Khoury MJ. Assessing value in biomedical research: the PQRST of appraisal and reward. JAMA. 2014;312(5):483–484. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nosek BA, Spies JR, Motyl M. Scientific utopia: II. Restructuring incentives and practices to promote truth over publishability. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7(6):615–631. doi: 10.1126/science.1059063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varmus H. Proliferation of National Institutes of Health. Science. 2001;291(5510):1903–1905. doi: 10.1126/science.1059063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council, Division on Earth and Life Studies, Board on Life Sciences, Committee on A Framework for Developing a New Taxonomy of Disease. Toward Precision Medicine: Building a Knowledge Network for Biomedical Research and a New Taxonomy of Disease. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Settles IH, Warner LR, Buchanan NT, Jones MK. Understanding psychology’s resistance to intersectionality theory using a framework of epistemic exclusion and invisibility. J Soc Issues. 2020;76(4):796–813. doi: 10.1111/josi.12403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller B. When is consensus knowledge based? Distinguishing shared knowledge from mere agreement. Synthese. 2013;190(7):1293–1316. doi: 10.1007/s11229-012-0225-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erosheva EA, Grant S, Chen M-C, Lindner MD, Nakamura RK, Lee CJ. NIH peer review: criterion scores completely account for racial disparities in overall impact scores. Sci Adv. 2020;6(23):eaaz4868. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaaw7238. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hekler E, Tiro J, Hunter C, Nebeker C. Precision health: the role of the social and behavioral sciences. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(11):805–826. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaaa018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institutes of Health. 2020. https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#

- 13.National Institutes of Health. 2021. https://www.nih.gov/ending-structural-racism

- 14.Borrell LN, Vaughan R. An AJPH Supplement toward a unified research approach for minority health and health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S6–S7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.304963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pérez-Stable EJ, Collins FS. Science visioning in minority health and health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.304962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funk C.2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/02/12/key-findings-about-americans-confidence-in-science-and-their-views-on-scientists-role-in-society

- 17.Akom AA. Black emancipatory action research: integrating a theory of structural racialisation into ethnographic and participatory action research methods. Ethnogr Educ. 2011;6(1):113–131. doi: 10.1080/17457823.2011.553083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crow MM. Time to rethink the NIH. Nature. 2011;471(7340):569–571. doi: 10.1038/471569a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]