Abstract

A reliable estimate of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies is increasingly important to track the spread of infection and define the true burden of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic review and a meta-analysis were conducted with the objective of estimating the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Africa. A systematic search of the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar electronic databases was conducted. Thirty-five eligible studies were included. Using meta-analysis of proportions, the overall seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was calculated as 16% (95% CI 13.1–18.9%). Based on antibody isotypes, 14.6% (95% CI 12.2–17.1%) and 11.5% (95% CI 8.7–14.2%) were seropositive for SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM, respectively, while 6.6% (95% CI 4.9–8.3%) were tested positive for both IgM and IgG. Healthcare workers (16.3%) had higher seroprevalence than the general population (11.7%), blood donors (7.5%) and pregnant women (5.7%). The finding of this systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) may not accurately reflect the true seroprevalence status of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Africa, hence, further seroprevalence studies across Africa are required to assess and monitor the growing COVID-19 burden.

Keywords: seroprevalence, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, antibodies, Africa, IgG, IgM, meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a highly contagious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), continues to rapidly spread across the world. By 25 February 2022, more than 430 million COVID-19 cases had been confirmed and more than 5,922,049 COVID-19-related deaths had been documented globally [1]. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has placed an unprecedented pressure on healthcare systems across the world. Taking into account that no country was adequately prepared for such a quickly spreading pandemic, the consequences of this outbreak have challenged the sustainability of healthcare systems, even in developed countries [2]. In Africa, the pandemic has been projected to be devastating due to the continent’s poor health systems, gaps in medical infrastructure, and vulnerability to infectious diseases [3,4]. However, the COVID-19 infection rates in African countries are now significantly lower than in other continents.

According to the Africa CDC, a total of 11,129,366 confirmed cases, 247,310 deaths and 10,331,607 recoveries had been documented in Africa by 25 February 2022 [5]. Indeed, the current statistics on the number of confirmed cases and deaths are useful in tracking the dynamics of the disease transmission; however, they are insufficient for estimating the proportion of the infected population [6]. Until now, most African countries have had limited access to viral testing by RT-PCR to screen all SARS-CoV-2 suspected patients or those are at risk of infection due to infrastructure limitations and intermittent supply shortages. In general, mild or asymptomatic individuals are often not screened and thus, the reported cases are unlikely to reflect all SARS-CoV-2 infections [7,8]. Accordingly, the true magnitude of this outbreak is most likely underestimated. In this context, seroprevalence estimates using anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies as markers of viral exposure are of utmost importance to identify the proportion of the previously infected population [9]. Detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (IgM or/and IgG) may accurately capture the true cumulative prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection [10], which is essential for better understanding the course and extent of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic [11], the contagiousness and the immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in vulnerable individuals as well as the community [12]. Furthermore, data on SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence amongst African population is important for assessing the success of the current public health interventions.

Seroprevalence investigations have been undertaken on a worldwide scale to provide insight into SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology. Monitoring changes in seroprevalence data over time is essential for anticipating the dynamics of any pandemic and planning an effective public health response. Accordingly, few systematic reviews have comprehensively synthesised seroprevalence findings related to anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies amongst the general or targeted group of the population. However, with the significant expansion of relevant literature, having an updated picture of anti-SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence is critical. With this background in mind, this SRMA was conducted to estimate the seroprevalence rate of SARS-CoV-2 in Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

In this study, a literature search, a study selection and reporting of the results were conducted on the basis of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Table S1) [13]. The protocol of this SRMA was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (registration number: CRD42021250601). A total of 4 electronic databases, namely, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar were systematically searched for studies published up to 1 July 2021, and those reporting the data on the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection amongst African population without language restriction. The detailed search strategy that was used for all databases is shown in Supplementary Table S2. In addition, reference lists of retrieved articles were tracked for identification of further relevant studies.

2.2. Data Management and Study Selection

At the initial stage, all of the identified records were combined in EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, London, UK). A strategy involving both auto- and hand-search was used for identification and removal of duplicates before the titles and abstracts of the remaining records were independently assessed for inclusion by three reviewers (K.H., Z.A.R. and N.I.). Subsequently, the full texts of the potentially eligible records were obtained and assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (S.A.H. and Z.M.). Any discrepancies or uncertainties were resolved by discussion and consensus.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The outcome of interest in this study is the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Africa. Overall seroprevalence was defined as detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM in combination or separately. Accordingly, original studies from African countries that report information on the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were considered eligible for inclusion, whilst comments, case reports, editorials and reviews were excluded. In addition, studies of non-human subjects or non-serological investigations were excluded.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (K.H. and M.A.I.) independently used the critical appraisal tool developed in the Joana Brigg’s Institute (JBI) for prevalence studies [14] to assess the methodological quality of each included study. The assessment results were further validated by the other authors and notable discrepancies were identified resolved by verification and discussion. The tool contains nine items and each of them corresponds to a ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’. Each study was assessed on the basis of the proportion of ‘yes’ answers given to the items. The high proportion (≥70%) of ‘yes’ refers to high-quality study (low risk of bias), whilst the moderate (50–69%) and low proportion (≤49%) of ‘yes’ refer to moderate- and low-quality studies, respectively [15,16,17].

2.5. Data Extraction

Following a full text review, relevant information was extracted by one reviewer (K.H.) using predesigned data collection sheet and later verified by four other reviewers (S.A.H., Z.A.R., N.I. and Z.M.). For all of the qualifying records, principal data were extracted on the number of subjects who were quantitatively or qualitatively tested for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody and how many were seropositive. In addition, information on the following variables were extracted: first author’s name, publication year, study design, country and place where the study was conducted, target population, recruitment location, gender, age, tested antibodies, serodiagnostic test and sensitivity and specificity of antibody tests. The United Nations Statistics Division African Region (Southern, Western, Central, Eastern and Northern Africa) was assigned to each study in accordance with the country of recruitment.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Seroprevalence was calculated as the ratio of seropositive individuals to the total participants by using the Metaprop command. Accordingly, the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [at 95% confidence intervals (CI)] was estimated for each included study and subsequently for Africa by pooling the seroprevalence rates of all studies through the use of the random-effect model. Heterogeneity between the studies was evaluated using I2 statistics in conjunction with Cochran’s Q-test. A cut-off value ≥ 75% of I2 statistic was used to indicate substantial heterogeneity [18], whilst a p value of <0.05 was considered to be a significant degree of heterogeneity. Publication bias was examined graphically using a funnel plot and statistically by Egger’s regression test.

2.7. Subgroup and Sensitivity Analysis

The potential sources of heterogeneity were further explored by estimating the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 based on different subgroups, including antibody isotypes, antibody tests, target population, study setting and African regions. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding (i) small studies (n < 200), (ii) low-quality studies (high risk of bias) and (iii) outlier studies.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

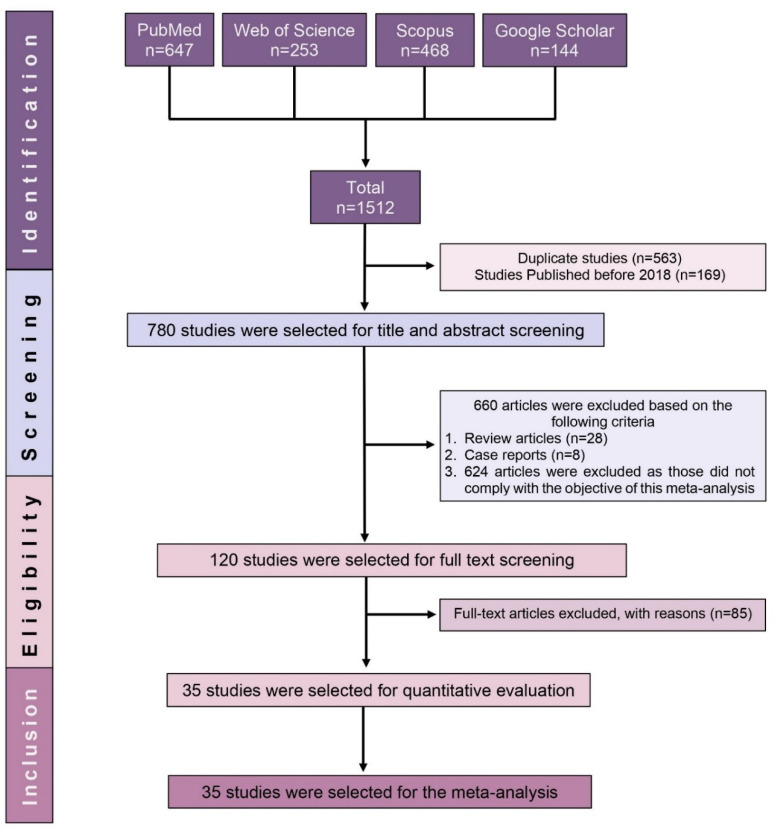

A total of 1512 records were retrieved in the initial search. Duplicates and studies published before 2018 were identified and removed, leaving 780 potential records. A further 660 studies were excluded following title and abstract screening. Subsequently, the full texts of the remaining 120 studies were assessed for eligibility, with 85 of them being excluded due to lack of seroprevalence data. Finally, only 35 fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in this SRMA (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 outlines the major characteristics of the 35 studies included in this SRMA. In total, 47,160 individuals recruited from 16 African countries and tested for the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were included. Of the 35 eligible studies, 31 are published articles and 4 are preprints. A total of 10 studies were conducted in Ethiopia and Kenya (5 studies each); 4 studies were conducted in Egypt, 3 were conducted each in Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Africa; 2 studies were carried out each in Cameroon, Libya and Zambia and 1 study was conducted in each of the following countries: Angola, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Malawi, Nigeria, South Sudan, Republic of the Congo, Togo and Zimbabwe. The regional distribution of the included studies revealed that 15 studies were from Eastern Africa, 7 studies were from Central Africa, 3 studies were from Southern Africa and 6 were each from Northern and Western Africa. The included studies utilised various serodiagnostic assays. The numbers of studies that used rapid diagnostic test (RDTs), ELISA, chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA), chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) and other tests were 15, 10, 3, 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Major characteristics of the included studies.

| Study ID [References] | Country | Study Period | Sample Size | Target Population | Recruitment Location | Method | Investigated Antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdella 2021 [19] | Ethiopia | July to September 2020 | 1856 | General population | Community based | RDT | IgM/IgG |

| Abdelmoniem 2021 [20] | Egypt | 1 to 14 June 2020 | 203 | HCWs | Hospital | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Adetifa 2021 [21] | Kenya | April to September 2020 | 9922 | Blood donors | Blood transfusion centre | ELISA | IgG |

| Assefa 2021 [22] | Ethiopia | March to April 2021 | 1447 | Pregnant women | Health facilities | RDT | Total antibodies |

| Batchi-Bouyou 2021 [23] | The Republic of Congo | April to July 2020 | 754 | General population | Community based | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Chibwana 2020 [24] | Malawi | 22 May to 19 June 2020 | 500 | HCWs | Hospital | ELISA | IgG |

| Etyang 2021 [25] | Kenya | 30 July to 4 December 2020 | 684 | HCWs | Hospital | ELISA | IgG |

| Fai 2021 [26] | Cameroon | June to August 2020 | 999 | Symptomatic and Asymptomatic | Community and Hospital | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Fwoloshi 2021 [27] | Zambia | July 2020 | 575 | HCWs | Health facilities | ELISA | IgG |

| George 2021 [28] | South Africa | August to October 2020 | 6477 | Outpatient | Hospital | CLIA | IgM and IgG |

| Goldblatt 2021 [29] | South Africa | 1 May to mid-July 2020 | 222 | HCWs | Hospital | ELISA | IgG |

| Halatoko 2020 [30] | Togo | April to May 2020 | 955 | Non-Specific | Multiple settings | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Kagucia 2021 [31] | Kenya | September to October 2020 | 830 | Others | Community based | ELISA | IgG |

| Kammon 2020 [32] | Libya | April to May 2020 | 219 | General population | Community and Hospital | RDT | IgM/IgG |

| Kassem 2020 [33] | Egypt | 1 to 14 June 2020 | 74 | HCWs | Hospital | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Katchunga 2021 [34] | DRC | May to August 2020 | 684 | Others | Health facilities | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Kempen 2020 [35] | Ethiopia | May 2020 | 99 | General population | Health facilities | CMIA | IgG |

| Milleliri 2021 [36] | Ivory Coast | July to October 2020 | 1687 | Others | Community based | RDT | IgG/IgM |

| Mostafa 2021 [37] | Egypt | April to June 2020 | 2282 | HCWs | Health facilities | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Mukhtar 2021 [38] | Egypt | May to June 2020 | 455 | HCWs | Hospital | RDT and CLIA | IgG |

| Mukwege 2021 [39] | DRC | July to August 2020 | 359 | HCWs | Hospital | RDT and ELISA | IgM and IgG |

| Mulenga 2021 [40] | Zambia | 4 to 27 July 2020 | 2704 | General population | Community based | ELISA | IgG |

| Nega 2020 [41] | Ethiopia | 23 to 28 April 2020 | 301 | General population | Community based | RDT | IgG/IgM |

| Ngere 2021 [42] | Kenya | November 2020 | 1164 | General population | Community based | EIA | IgM and IgG |

| Nkuba 2021 [43] | DRC | October to November 2020 | 1080 | General population | Community based | Luminex-based assay | IgG |

| Nwosu 2021 [44] | Cameroon | October to November 2020 | 971 | General population | Community based | RDT | IgM/IgG |

| Olayanju 2021 [45] | Nigeria | December 2019 to April 2020 | 133 | HCWs | Hospital | ELISA | IgG |

| Quashie 2021 [46] | Ghana | July to September 2020 | 1305 | Non-Specific | Multiple settings | RDT | IgM and IgG |

| Rusakaniko 2021 [47] | Zimbabwe | June 2020 | 635 | HCWs | Health facilities | RDT | IgG and IgM |

| Sebastião 2021 [48] | Angola | July to September 2020 | 660 | General population | community based | ELFA | IgM and IgG |

| Shaw 2021 [49] | South Africa | 17 August to 4 September | 405 | Others | Community based | CMIA | IgG |

| Shaweno 2021 [50] | Ethiopia | June to July 2020 | 684 | General population | Community based | CMIA | IgG |

| Uyoga 2021 [51] | Kenya | April to June 2020 | 3098 | Blood donors | Blood transfusion centre | ELISA | IgG |

| Wiens 2021 [52] | South Sudan | August to September 2020 | 1840 | General population | Community based | ELISA | IgG |

| Zarmouh 2021 [53] | Libya | 18 to 21 April 2020 | 897 | General population | Community based | CLIA | IgM and IgG |

Key: DRC: Democratic Republic of the Congo, HCWs: Healthcare workers, RDT: Rapid Diagnostic Test, ELISA: Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay, CLIA: Chemiluminescence Immunoassay, CMIA: Chemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay, EIA: Enzyme immunoassay and ELFA: Enzyme-linked fluorescent assay.

3.3. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies

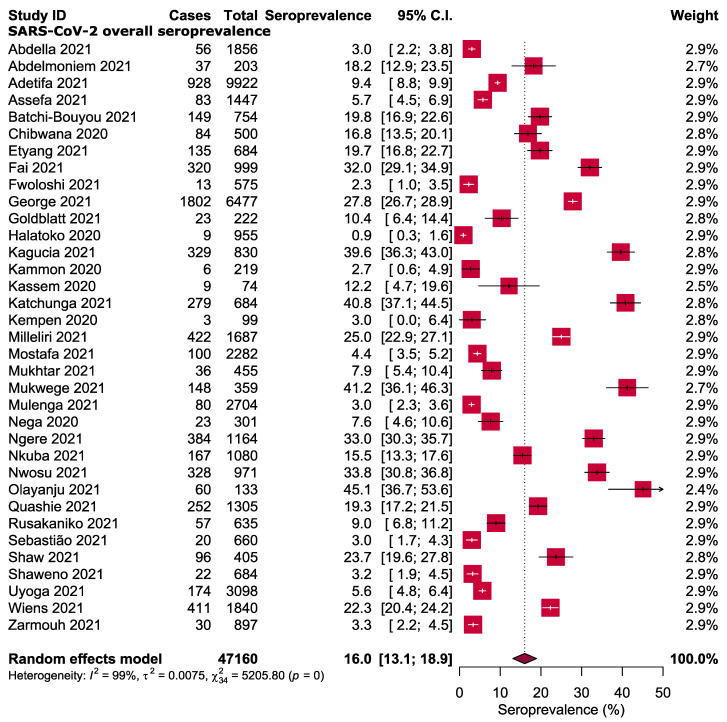

The forest plot in Figure 2 shows the estimated seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies from the included studies and the corresponding 95% CI. The lowest rate of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was 0.9% in Togo [30], whilst the highest of 45.1% was reported in Nigeria [45]. By using the random-effect model, the pooled overall seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was calculated as 16.0%, with a heterogeneity of I2 99% (p < 0.001, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Africa [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

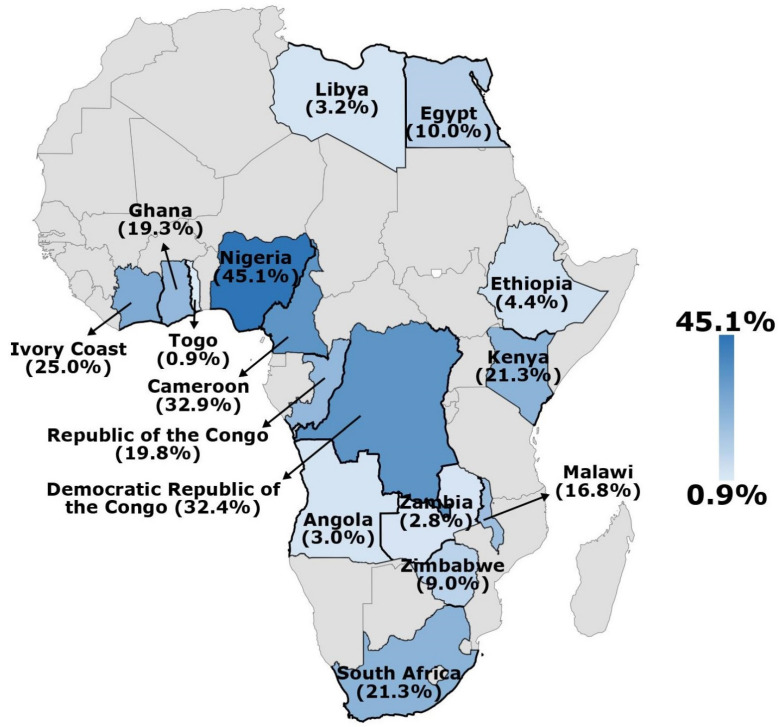

Subgroup analysis was carried out to identify factors that may have contributed to the high degree of heterogeneity. Table 2 and Figure S1 show the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 across various subgroups. The pooled seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection based on antibody isotypes showed that 14.6% participants reported in 30 studies were seropositive for IgG against SARS-CoV-2, 11.5% recruited in 15 studies were seropositive for IgM and 6.6% of them in nine studies were tested positive for IgM and IgG. Some similar overall estimates were observed when anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were measured by ELISA (16.5%), CMIA (9.8%) and RDTs (15.5%), whilst it was slightly low when CLIA was used (15.6%). Furthermore, the overall seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in different countries in Africa is presented in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses estimating the pooled seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Africa.

| Subgroups | Pooled Seroprevalence [95% CIs] (%) | Number of Studies Analysed | Total Number of Patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody isotypes | |||

| Overall IgG | 14.6 [12.2–17.1] | 30 | 34,113 |

| Overall IgM | 11.5 [8.7–14.2] | 15 | 10,882 |

| IgG and IgM | 6.6 [4.9–8.3] | 9 | 7557 |

| Antibody tests | |||

| Rapid diagnostic test | 15.5 [11.0–20.1] | 15 | 14,372 |

| Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay | 16.5 [12.2–20.8] | 10 | 20,508 |

| Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay | 9.8 [0.0–20.7] | 3 | 1188 |

| Chemiluminescence Immunoassay | 15.6 [0.0–39.6] | 2 | 7347 |

| Target population | |||

| General population | 11.7 [7.4–16.0] | 13 | 13,229 |

| Healthcare workers | 16.3 [11.5–21.2] | 11 | 6122 |

| Blood donors | 7.5 [3.8–11.2] | 2 | 13,020 |

| Pregnant women | 5.7 [4.5–6.9] | 1 | 1447 |

| Settings | |||

| Community | 16.7 [11.7–21.8] | 14 | 15,833 |

| Hospital | 21.9 [14.8–29.0] | 9 | 9107 |

| Healthcare facilities | 10.6 [5.1–16.1] | 6 | 5722 |

| Blood transfusion centre | 7.5 [3.8–11.2] | 2 | 13,020 |

| Regions | |||

| Northern Africa | 6.5 [4.1–8.9] | 6 | 4130 |

| Central Africa | 26.5 [14.6–38.4] | 7 | 5507 |

| Eastern Africa | 12.1 [8.8–15.3] | 15 | 26,339 |

| Western Africa | 22.0 [6.7–37.6] | 4 | 4080 |

| Southern Africa | 20.7 [10.4–31.1] | 3 | 7104 |

CIs: confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Overall seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in different countries in Africa.

The pooled estimates of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence was highest amongst the participants recruited from hospitals (21.9%), followed by community (16.7%), healthcare facilities (10.6%) and blood transfusion centres (7.5%). Based on the target group, HCWs were found to have a seroprevalence of 16.3%; the general population had 11.7% and blood donors and pregnant women had 7.5% and 5.7%, respectively. The seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies based on the geographical regions of Africa was 26.5% in Central Africa, 22.0% in Western Africa, 20.7% in Southern Africa, 12.1% in Eastern Africa and only 6.5% in Northern Africa.

3.5. Quality Assessment and Publication Bias

Detailed information about the quality assessment of all included studies is presented in Supplementary Table S3. According to the JBI rating system, the risk of bias was high in 5 (14.3%) studies, moderate in 12 (34.3%) studies and low in 18 (51.4%) studies. As visually illustrated by the asymmetrical funnel plot and statistically confirmed by Egger test (p = 0.002), an evidence of significant publication bias was found within the included studies (Figure S2).

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis revealed that excluding small studies, low-quality studies and outlier studies (Figure S3) had no significant effect on the overall seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The seropositivity rate remained within the 95% CI of the respective overall seroprevalence (Figure S4), indicating that the results generated in this SRMA are robust and reliable.

4. Discussion

The current uncertainties around the real counts of SARS-CoV-2 cases in Africa highlighted the need for obtaining credible seroprevalence estimates of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, which may indicate the true extent of the COVID-19 pandemic in the region. Indeed, several previous investigations have verified that the actual number of infected individuals are much higher than the reported cases [54,55]. In this SRMA, the relevant literature was critically reviewed to provide an updated overview of the continent-wide SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence.

The meta-analysis of data obtained from 47,160 individuals in 35 eligible studies showed a considerable variation in the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies amongst the included studies and thus between African nations. The results revealed that the SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity amongst African population ranged from 0.9% to 45.1%, with an estimated overall seroprevalence of 16.0%. This finding is higher than the previous estimates of global seroprevalence [56,57]. It is also higher than the results of other population-based studies and nationwide serosurvey conducted in Europe [58,59,60], USA [61,62] India (7.1%) [63] and Brazil [64]. By contrast, it is relatively low compared with other rates reported from Iran, USA, Sweden, and India [54,65,66,67]. The observed variations in seroprevalence estimates between studies, countries and regions may be attributed to a number of factors, including public health responses, adherence to control measures and differences in community transmission. In addition, variations in seropositivity reflect the differences in study designs, study populations, antibody tests and data collecting dates.

Indeed, additional information is required before using serological testing as a sole basis to confirm or exclude active SARS-CoV-2 infection [68]. Studies are urgently needed to assess the kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 antibody response and how it could be used to interpret serological results. Until then, the detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM antibodies in combination with molecular testing could significantly improve COVID-19 diagnosis and play an essential role in assessing immunological responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection [69]. In the present SRMA, the pooled seroprevalence of IgG, IgM, and IgG and IgM antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were estimated to be 14.6%, 11.5%, and 6.6%, respectively. However, the relatively high rate of positive IgG cases in this study was lower than the 67.44% found in a previous meta-analysis [70]. Similar to numerous other systematic reviews, various serodiagnostic platforms are available for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, with RDTs being the most commonly used. In fact, comparing seroprevalence rates across studies is confounded by the variable efficiency of diagnostic tests. However, slight variations in the overall estimates were found when anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were assessed using ELISA, CMIA and RDTs, possibly because the majority of diagnostic tests used have high sensitivity and specificity.

Subgroup analysis regarding the serological status of SARS-CoV-2 according to study population and recruitment site was conducted. As expected, the highest burden of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were found amongst HCWs (16.3%) compared with general population (11.7%), blood donors (7.5%) and pregnant women (5.7%). Several studies have highlighted the potential of SARS-CoV-2 occupational transmission amongst HCWs, as they are on the frontlines of the COVID-19 response and, in turn, are more vulnerable to viral transmission [71,72,73]. The seropositivity rate amongst African HCWs was higher than the pooled estimates of many previous meta-analysis studies that included a global or regional data representation [74,75,76]. However, it is unknown whether HCWs have a higher seroprevalence rate as a result of their vaccination status, considering the fact that HCWs prioritised COVID-19 vaccination. Although little is known regarding the extent to which African HCWs adhere to infection prevention and control measures, compliance with to these mitigation measures and the appropriate use of personal protective equipment are critical for reducing infection risk amongst HCWs [77,78].

On the basis of the geographical regions of Africa, the meta-analysis results indicated that Central and Western Africa had higher seroprevalence rates (26.5% and 22.0%, respectively) than Southern (20.7%), Eastern (12.1%) and Northern (6.5%) Africa. Considering the limited evidence regarding the influence of environmental and demographic factors on SARS-CoV-2 transmission [79], neither the high seropositivity in Central Africa nor the low seropositivity in Northern Africa could accurately reflect the real status in these regions due to the few number of eligible studies in some regions. For instance, only one nation from Southern Africa and two from Northern Africa were included. Indeed, finding of one or two studies is inconclusive and should not be generalised. Since data from only 16 African countries were included in the analysis, a considerable proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Africa remain unreported. The lack of baseline data on the seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 in many African countries is critical because current information is necessary to understand the spread of COVID-19 in those countries. Therefore, further surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence is required to assess and monitor the increasing COVID-19 burden.

As this SRMA provides the most up-to-date comprehensive estimation of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence on the basis of a critical review of available literature, its findings should be interpreted in the context of several important limitations. Firstly, only 16 of the 54 African countries were included in this study. Besides, adequate representation in studies conducted in Southern and Northern Africa is lacking. Secondly, the reported seroprevalence in individual studies may be underestimated or overestimated depending on the sensitivity and specificity of the antibody test used. Furthermore, some of the included studies did not report the sensitivity and specificity of the antibody tests. Thirdly, a high level of heterogeneity was detected between individual studies and the asymmetry of the funnel plot suggested the existence of publication bias, both of which are common in such meta-analysis.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, based on the comprehensive review and meta-analysis of available data on SARS-CoV-2 until 1 July 2021, the seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 in Africa was estimated to be 16.0%. However, due to the limited number of relevant studies, the high level of heterogeneity and the large gap in studies conducted in most African countries, the findings of this SRMA may not accurately reflect the true seroprevalence status of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Africa. Therefore, further seroprevalence studies across Africa are required to assess and monitor the growing COVID-19 burden. However, in order to better interpret the results and provide clinically meaningful and valuable recommendations to healthcare providers and test recipients, several factors must be considered when conducting such seroprevalence studies: whether the person is symptomatic or asymptomatic at the time of testing; positive or negative status of IgM and IgG; as well as the test device quality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19127257/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist. Table S2: Detailed Search Strategy. Table S3: Quality assessment of the included studies. Figure S1: Subgroup analyses. Figure S2: Funnel plot. Figure S3: Galbraith plot. Figure S4: Sensitivity analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.M., K.H. and N.I.; methodology, K.H., S.A.H. and A.R.Z.; software, M.A.I.; validation, S.A.H., A.R.Z., N.I. and Z.M.; formal analysis, M.A.I.; investigation, M.A.I. and K.H.; resources S.A.H. and A.R.Z.; data curation, Z.M., K.H. and N.I.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.M. and K.H.; visualization, M.A.I.; supervision, K.H.; project administration, Z.M. and K.H.; funding acquisition, Z.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available within the manuscript and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

The APC was funded by the Research Creativity and Management (RCMO), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) and the School of Medical Sciences, USM.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. [(accessed on 25 February 2022)]. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R., Thome B., Parker M., Glickman A., Zhang C., Boyle C., Smith M., Phillips J.P. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amadu I., Ahinkorah B.O., Afitiri A.-R., Seidu A.-A., Ameyaw E.K., Hagan J.E., Jr., Duku E., Aram S.A. Assessing sub-regional-specific strengths of healthcare systems associated with COVID-19 prevalence, deaths and recoveries in Africa. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0247274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nkengasong J.N., Mankoula W. Looming threat of COVID-19 infection in Africa: Act collectively, and fast. Lancet. 2020;395:841–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Dashboard. 2022. [(accessed on 25 February 2022)]. Available online: https://africacdc.org/covid-19/

- 6.Roda W.C., Varughese M.B., Han D., Li M.Y. Why is it difficult to accurately predict the COVID-19 epidemic? Infect. Dis. Model. 2020;5:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimball A., Hatfield K.M., Arons M., James A., Taylor J., Spicer K., Bardossy A.C., Oakley L.P., Tanwar S., Chisty Z. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility—King County, Washington, March 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:377. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizumoto K., Kagaya K., Zarebski A., Chowell G. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25:2000180. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sood N., Simon P., Ebner P., Eichner D., Reynolds J., Bendavid E., Bhattacharya J. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2–Specific Antibodies Among Adults in Los Angeles County, California, on April 10–11, 2020. JAMA. 2020;323:2425–2427. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X., Sun J., Nie S., Li H., Kong Y., Liang M., Hou J., Huang X., Li D., Ma T., et al. Seroprevalence of immunoglobulin M and G antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in China. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1193–1195. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Vu S., Jones G., Anna F., Rose T., Richard J.-B., Bernard-Stoecklin S., Goyard S., Demeret C., Helynck O., Escriou N., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in France: Results from nationwide serological surveillance. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3025. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munster V.J., Koopmans M., van Doremalen N., van Riel D., de Wit E. A novel coronavirus emerging in China—key questions for impact assessment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page M.J., Moher D., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munn Z., Moola S., Lisy K., Riitano D., Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Islam M.A., Alam S.S., Kundu S., Hossan T., Kamal M.A., Cavestro C.J. Prevalence of headache in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14,275 patients. Front. Neurol. 2020;11:562634. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.562634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saniasiaya J., Islam M.A., Abdullah B.J.O.H., Surgery N. Prevalence and characteristics of taste disorders in cases of COVID-19: A meta-analysis of 29,349 patients. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021;165:33–42. doi: 10.1177/0194599820981018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajissa K., Islam M.A., Sanyang A.M., Mohamed Z. Prevalence of intestinal protozoan parasites among school children in africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022;16:e0009971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang C.-T., Ang J.-Y., Islam M.A., Chan H.-K., Cheah W.-K., Gan S.H. Prevalence of Drug-Related Problems and Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in Malaysia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 37,249 Older Adults. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:187. doi: 10.3390/ph14030187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdella S., Riou S., Tessema M., Assefa A., Seifu A., Blachman A., Abera A., Moreno N., Irarrazaval F., Tollera G., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in urban and rural Ethiopia: Randomized household serosurveys reveal level of spread during the first wave of the pandemic. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100880. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdelmoniem R., Fouad R., Shawky S., Amer K., Elnagdy T., Hassan W.A., Ali A.M., Ezzelarab M., Gaber Y., Badary H.A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among asymptomatic healthcare workers of the emergency department in a tertiary care facility. J. Clin. Virol. 2021;134:104710. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adetifa I.M., Uyoga S., Gitonga J.N., Mugo D., Otiende M., Nyagwange J., Karanja H.K., Tuju J., Wanjiku P., Aman R., et al. Temporal trends of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in transfusion blood donors during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in Kenya. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.09.21251404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assefa N., Regassa L.D., Teklemariam Z., Oundo J., Madrid L., Dessie Y., Scott J. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in women attending antenatal care in eastern Ethiopia: A facility-based surveillance. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e055834. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batchi-Bouyou A.L., Ingoba L.L., Ndounga M., Vouvoungui J.C., Mapanguy C.C.M., Boumpoutou K.R., Ntoumi F.J.D. High SARS-CoV-2 IgG/IGM seroprevalence in asymptomatic Congolese in Brazzaville, the Republic of Congo. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;106:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chibwana M., Jere K., Kamng’ona R., Mandolo J., Katunga-Phiri V., Tembo D., Mitole N., Musasa S., Sichone S., Lakudzala A., et al. High SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in health care workers but relatively low numbers of deaths in urban Malawi [version 2; peer review: 2 approved] Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:199. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16188.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Etyang A.O., Lucinde R., Karanja H., Kalu C., Mugo D., Nyagwange J., Gitonga J., Tuju J., Wanjiku P., Karani A., et al. Seroprevalence of Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 among Health Care Workers in Kenya. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021;74:288–293. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fai K.N., Corine T.M., Bebell L.M., Mbroingong A.B., Nguimbis E.T., Nsaibirni R., Mbarga N.F., Eteki L., Nikolay B., Essomba R.G. Serologic Response to SARS-CoV-2 in an African Population. Sci. Afr. 2021;12:e00802. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fwoloshi S., Hines J.Z., Barradas D.T., Yingst S., Siwingwa M., Chirwa L., Zulu J.E., Banda D., Wolkon A., Nikoi K. Prevalence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) among Health Care Workers—Zambia, July 2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;3:e1321–e1328. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.George J.A., Khoza S., Mayne E., Dlamini S., Kone N., Jassat W., Chetty K., Centner C.M., Pillay T., Maphayi M., et al. Sentinel seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Gauteng Province, South Africa, August—October 2020. South Afr. Med. J. Suid-Afrik. Tydskr. Vir Geneeskd. 2021;111:1078–1083. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i11.15669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldblatt D., Johnson M., Falup-Pecurariu O., Ivaskeviciene I., Spoulou V., Tamm E., Wagner M., Zar H.J., Bleotu L., Ivaskevicius R., et al. Cross-sectional prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in healthcare workers in paediatric facilities in eight countries. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021;110:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halatoko W.A., Konu Y.R., Gbeasor-Komlanvi F.A., Sadio A.J., Tchankoni M.K., Komlanvi K.S., Salou M., Dorkenoo A.M., Maman I., Agbobli A.J. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among high-risk populations in Lomé (Togo) in 2020. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0242124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagucia E.W., Gitonga J.N., Kalu C., Ochomo E., Ochieng B., Kuya N., Karani A., Nyagwange J., Karia B., Mugo D., et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody seroprevalence among truck drivers and assistants in Kenya. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021;8:ofab314. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kammon A.M., El-Arabi A.A., Erhouma E.A., Mehemed T.M., Mohamed O.A. Seroprevalence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among public community and health-care workers in Alzintan City of Libya. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.25.20109470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kassem A.M., Talaat H., Shawky S., Fouad R., Amer K., Elnagdy T., Hassan W.A., Tantawi O., Abdelmoniem R., Gaber Y., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers of a gastroenterological service in a tertiary care facility. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2020;21:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katchunga P.B., Murhula A., Akilimali P., Zaluka J.C., Karhikalembu R., Makombo M., Bisimwa J., Mubalama E. Séroprévalence des anticorps anti-SARS-CoV-2 parmi les voyageurs et travailleurs dépistés à la clinique Saint Luc de Bukavu, à l’Est de la République Démocratique du Congo, de mai en août 2020. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021;38:93. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.93.26663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kempen J.H., Abashawl A., Suga H.K., Difabachew M.N., Kempen C.J., Debele M.T., Menkir A.A., Assefa M.T., Asfaw E.H., Habtegabriel L.B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Serosurvey in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;103:2022–2023. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milleliri J.M., Coulibaly D., Nyobe B., Rey J.-L., Lamontagne F., Hocqueloux L., Giaché S., Valery A., Prazuck T. SARS-CoV-2 infection in Ivory Coast: A serosurveillance survey among gold mine workers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104:1709. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mostafa A., Kandil S., El-Sayed M.H., Girgis S., Hafez H., Yosef M., Saber S., Ezzelarab H., Ramadan M., Algohary E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion among 4040 Egyptian healthcare workers in 12 resource-limited healthcare facilities: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;104:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukhtar A., Afishawy M., Alkhatib E., Hosny M., Ollaek M., Elsayed A., Salem M.R., Ghaith D. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers in a non-COVID-19 Teaching University Hospital. J. Public Health Res. 2021;10:2102. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2021.2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukwege D., Byabene A.K., Akonkwa E.M., Dahma H., Dauby N., Buhendwa J.-P.C., Le Coadou A., Montesinos I., Bruyneel M., Cadière G.-B., et al. High SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence in Healthcare Workers in Bukavu, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104:1526. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulenga L.B., Hines J.Z., Fwoloshi S., Chirwa L., Siwingwa M., Yingst S., Wolkon A., Barradas D.T., Favaloro J., Zulu J.E., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in six districts in Zambia in July, 2020: A cross-sectional cluster sample survey. Lancet Glob. Health. 2021;9:e773–e781. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00053-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nega B., Addissie A., Mamo G., Deyessa N., Abebe T., Abagero A., Ayele W., Abebe W., Haile T., Argaw R., et al. Sero-prevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.13.337287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ngere I.A., Dawa J., Hunsperger E., Otieno N., Masika M., Amoth P., Makayotto L., Nasimiyu C., Gunn B.M., Nyawanda B., et al. High seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 but low infection fatality ratio eight months after introduction in Nairobi, Kenya. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;112:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nkuba A.N., Makiala S.M., Guichet E., Tshiminyi P.M., Bazitama Y.M., Yambayamba M.K., Kazenza B.M., Kabeya T.M., Matungulu E.B., Baketana L.K., et al. High prevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after the first wave of COVID-19 in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Results of a cross-sectional household-based survey. Wellcome Open Res. 2021;6:173. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16890.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nwosu K., Fokam J., Wanda F., Mama L., Orel E., Ray N., Meke J., Tassegning A., Takou D., Mimbe E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence and associated risk factors in an urban district in Cameroon. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5851. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25946-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olayanju O., Bamidele O., Edem F., Eseile B., Amoo A., Nwaokenye J., Udeh C., Oluwole G., Odok G., Awah N. SARS-CoV-2 Seropositivity in Asymptomatic Frontline Health Workers in Ibadan, Nigeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104:91–94. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quashie P.K., Mutungi J.K., Dzabeng F., Oduro-Mensah D., Opurum P.C., Tapela K., Udoakang A.J., Asante I., Paemka L., WACCBIP COVID-19 Team Trends of SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in selected regions across Ghana. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.25.21256067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rusakaniko S., Sibanda E.N., Mduluza T., Tagwireyi P., Dhlamini Z., Ndhlovu C.E., Chandiwana P., Chiwambutsa S., Lim R.M., Scott F. SARS-CoV-2 Serological testing in frontline health workers in Zimbabwe. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15:e0009254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sebastião C.S., Galangue M., Gaston C., Van-Dunen R., Jandondo D., Neto Z., de Vasconcelos J.N., Morais J. Serological identification of past and recent SARS-CoV-2 infection through antibody screening in Luanda, Angola. Health Sci. Rep. 2021;4:e280. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw J.A., Meiring M., Cummins T., Chegou N.N., Claassen C., Du Plessis N., Flinn M., Hiemstra A., Kleynhans L., Leukes V., et al. Higher SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in workers with lower socioeconomic status in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0247852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaweno T., Abdulhamid I., Bezabih L., Teshome D., Derese B., Tafesse H., Shaweno D. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibody among individuals aged above 15 years and residing in congregate settings in Dire Dawa city administration, Ethiopia. Trop. Med. Health. 2021;49:55. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00347-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uyoga S., Adetifa I.M., Karanja H.K., Nyagwange J., Tuju J., Wanjiku P., Aman R., Mwangangi M., Amoth P., Kasera K.J.S. Seroprevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Kenyan blood donors. Science. 2021;371:79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.abe1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiens K.E., Mawien P.N., Rumunu J., Slater D., Jones F.K., Moheed S., Caflisch A., Bior B.K., Jacob I.A., Lako R.L., et al. Seroprevalence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 IgG in Juba, South Sudan, 2020(1) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27:1598–1606. doi: 10.3201/eid2706.210568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zarmouh A., Elaswdi H., Elakhtel E., Abufalgha K., Taraina M. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Misrata, Libya: A Population-Based Surveillance Study. Open J. Epidemiol. 2021;11:101. doi: 10.4236/ojepi.2021.111010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shakiba M., Nazari S.S.H., Mehrabian F., Rezvani S.M., Ghasempour Z., Heidarzadeh A. Seroprevalence of COVID-19 virus infection in Guilan province, Iran. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.26.20079244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doi A., Iwata K., Kuroda H., Hasuike T., Nasu S., Kanda A., Nagao T., Nishioka H., Tomii K., Morimoto T. Estimation of seroprevalence of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) using preserved serum at an outpatient setting in Kobe, Japan: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2020;11:100–747. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rostami A., Sepidarkish M., Leeflang M., Riahi S.M., Shiadeh M.N., Esfandyari S., Mokdad A.H., Hotez P.J., Gasser R.B. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;27:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bobrovitz N., Arora R.K., Cao C., Boucher E., Liu M., Donnici C., Yanes-Lane M., Whelan M., Perlman-Arrow S., Chen J. Global seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0252617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stringhini S., Wisniak A., Piumatti G., Azman A.S., Lauer S.A., Baysson H., De Ridder D., Petrovic D., Schrempft S., Marcus K., et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Geneva, Switzerland (SEROCoV-POP): A population-based study. Lancet. 2020;396:313–319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31304-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pollán M., Pérez-Gómez B., Pastor-Barriuso R., Oteo J., Hernán M.A., Pérez-Olmeda M., Sanmartín J.L., Fernández-García A., Cruz I., Fernández de Larrea N., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): A nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet. 2020;396:535–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31483-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zejda J.E., Brożek G.M., Kowalska M., Barański K., Kaleta-Pilarska A., Nowakowski A., Xia Y., Buszman P. Seroprevalence of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in a random sample of inhabitants of the katowice region, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:3188. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bendavid E., Mulaney B., Sood N., Shah S., Bromley-Dulfano R., Lai C., Weissberg Z., Saavedra-Walker R., Tedrow J., Bogan A., et al. COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021;50:410–419. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenberg E.S., Tesoriero J.M., Rosenthal E.M., Chung R., Barranco M.A., Styer L.M., Parker M.M., John Leung S.-Y., Morne J.E., Greene D., et al. Cumulative incidence and diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in New York. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020;48:23–29.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murhekar M.V., Bhatnagar T., Selvaraju S., Saravanakumar V., Thangaraj J.W.V., Shah N., Kumar M.S., Rade K., Sabarinathan R., Asthana S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in India, August–September, 2020: Findings from the second nationwide household serosurvey. Lancet Glob. Health. 2021;9:e257–e266. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30544-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hallal P.C., Hartwig F.P., Horta B.L., Silveira M.F., Struchiner C.J., Vidaletti L.P., Neumann N.A., Pellanda L.C., Dellagostin O.A., Burattini M.N., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in Brazil: Results from two successive nationwide serological household surveys. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8:e1390–e1398. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30387-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naranbhai V., Chang C.C., Beltran W.F.G., Miller T.E., Astudillo M.G., Villalba J.A., Yang D., Gelfand J., Bernstein B.E., Feldman J., et al. High Seroprevalence of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Chelsea, Massachusetts. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;222:1955–1959. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindahl J.F., Hoffman T., Esmaeilzadeh M., Olsen B., Winter R., Amer S., Molnár C., Svalberg A., Lundkvist Å. High seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in elderly care employees in Sweden. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2020;10:1789036. doi: 10.1080/20008686.2020.1789036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.George C.E., Inbaraj L.R., Chandrasingh S., de Witte L.P. High seroprevalence of COVID-19 infection in a large slum in South India; what does it tell us about managing a pandemic and beyond? Epidemiol. Infect. 2021;149:e39. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.West R., Kobokovich A., Connell N., Gronvall G.K. COVID-19 Antibody Tests: A Valuable Public Health Tool with Limited Relevance to Individuals. Trends Microbiol. 2020;29:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y., Wang X., Yuan J., Li T., Li J., et al. Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in Patients With Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:2027–2034. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fathi M., Vakili K., Sayehmiri F., Mohamadkhani A., Ghanbari R., Hajiesmaeili M., Rezaei-Tavirani M. Seroprevalence of Immunoglobulin M and G Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 Virus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. Iran. J. Immunol. 2021;18:34–46. doi: 10.22034/iji.2021.87723.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canova V., Lederer Schläpfer H., Piso R.J., Droll A., Fenner L., Hoffmann T., Hoffmann M. Transmission risk of SARS-CoV-2 to healthcare workers–observational results of a primary care hospital contact tracing. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2020;150:w20257. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilson N., Norton A., Young F., Collins D. Airborne transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 to healthcare workers: A narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1086–1095. doi: 10.1111/anae.15093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Godderis L., Boone A., Bakusic J. COVID-19: A new work-related disease threatening healthcare workers. Occup. Med. 2020;70:315–316. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hossain A., Nasrullah S.M., Tasnim Z., Hasan M.K., Hasan M.M. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies among health care workers prior to vaccine administration in Europe, the USA and East Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;33:100770. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galanis P., Vraka I., Fragkou D., Bilali A., Kaitelidou D. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and associated factors in health care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;108:120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sahu A.K., Amrithanand V., Mathew R., Aggarwal P., Nayer J., Bhoi S. COVID-19 in health care workers–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;38:1727–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kampf G., Brüggemann Y., Kaba H.E.J., Steinmann J., Pfaender S., Scheithauer S., Steinmann E. Potential sources, modes of transmission and effectiveness of prevention measures against SARS-CoV-2. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;106:678–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pan A., Liu L., Wang C., Guo H., Hao X., Wang Q., Huang J., He N., Yu H., Lin X., et al. Association of Public Health Interventions With the Epidemiology of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1915–1923. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Castilla J., Fresán U., Trobajo-Sanmartín C., Guevara M. Altitude and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the First Pandemic Wave in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:2578. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available within the manuscript and Supplementary Materials.