Abstract

Bivariate correlation coefficients (BCCs) are often calculated to gauge the relationship between two variables in medical research. In a family-type clustered design where multiple participants from same units/families are enrolled, BCCs can be defined and estimated at various hierarchical levels (subject level, family level and marginal BCC). Heterogeneity usually exists between subject groups and, as a result, subject level BCCs may differ between subject groups. In the framework of bivariate linear mixed effects modeling, we define and estimate BCCs at various hierarchical levels in a family-type clustered design, accommodating subject group heterogeneity. Simplified and modified asymptotic confidence intervals are constructed to the BCC differences and Wald type tests are conducted. A real-world family-type clustered study of Alzheimer disease (AD) is analyzed to estimate and compare BCCs among well-established AD biomarkers between mutation carriers and non-carriers in autosomal dominant AD asymptomatic individuals. Extensive simulation studies are conducted across a wide range of scenarios to evaluate the performance of the proposed estimators and the type-I error rate and power of the proposed statistical tests.

Abbreviations: BCC: bivariate correlation coefficient; BLM: bivariate linear mixed effects model; CI: confidence interval; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; DIAN: The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network; SA: simple asymptotic; MA: modified asymptotic

KEYWORDS: Bivariate correlation coefficient, bivariate linear mixed effects model, parameter estimation, confidence interval, hypothesis testing, type-I error/size and power

Introduction

The motivating study

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease with accumulations of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. The main hallmark protein of amyloid plaques in AD is -amyloid , and the tangles are composed of abnormally hyper-phosphorylated tau protein [1–4]. (peptide fragment derived from the larger amyloid precursor protein) and total or phosphorylated tau protein [5] measured in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF, contiguous with the extracellular space of the brain) by immunoassays are two key biomarkers of these AD pathologies [2,6–11]. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to assess brain atrophy, and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging technique using the Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) radiotracer has been adopted as a non-invasive means to measure abnormal amyloid deposition in the brain [12,13]. These are considered established biomarkers to investigate pathophysiological changes in CSF and brain in the AD field.

Due to the long natural course of the disease and the fact that no effective treatment is currently available at the symptomatic AD stage, AD research has recently shifted its focus from symptomatic AD patients to prodromal asymptomatic individuals with no manifest of clinical symptoms, with the objective of early diagnosis and timely intervention before clinical symptoms manifest. The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) is an international study launched in 2008 to understand autosomal dominant AD, a rare genetic form of AD that is caused by mutations in one of three genes including the Amyloid Precursor Protein, presenilin 1 and presenilin 2 [14–16]. The mutation carriers of these genes develop AD typically before 65 years of age. A family-type clustered design was adopted for DIAN to enroll adult individuals whose parents are known carriers of these causative mutations and follow them regularly for clinical evaluation, CSF biomarker analysis, PET and MRI imaging, and cognitive assessments. The parents themselves were not enrolled. Given the fact that the vast majority of DIAN participants do not want to know their genetic status, both mutation carriers and non-carriers participate in the study. A fundamentally important scientific question is how biomarkers across different modalities (e.g. CSF, MRI, PET) are correlated, and whether such correlations are different between mutation non-carriers and carriers, especially among those who are asymptomatic. Although AD biomarker correlation has been well studied in literature using simple random samples in which data from different subjects can be considered as statistically independent [17,18], DIAN poses analytical challenges because of its family-type clustered design and subject heterogeneities.

In this paper, we utilize the DIAN study data to answer scientifically important questions: Do biomarkers across different modalities, as well as within the same modalities (e.g. CSF, MRI, PET), show different relationships between cognitively normal mutation carriers and non-carriers? Is the difference statistically significant? Specifically, we propose to estimate group-specific (mutation carrier and non-carrier) bivariate correlation coefficients (BCCs) and compare the group-specific BCCs via hypothesis testing and confidence interval construction. We also conduct extensive simulations to demonstrate the asymptomatic and small sample performance of the proposed methods.

Bivariate correlation coefficients

The relationship between two variables (e.g. biomarkers in a biomedical study) can be gauged by BCCs. When all individuals in a study are independent, the Pearson product moment method can be used to calculate the simple BCC between two biomarkers. In a clustered design, however, the existence of multiple hierarchical levels dictates that various BCCs can be defined corresponding to the levels. The existing literature [19–22] predominantly focuses on repeated measures type of clustered design or/and real data analysis studying impacts of different covariance structures. The ‘hidden correlation’ [23] is proposed in a bivariate linear mixed effect model framework to estimate correlation between two variables but focus on the cluster level in a repeated measures design. Mean, dispersion and correlation matrix of non-normal multivariate correlated longitudinal data were jointly modeled [24] via unconstrained parameterization of covariance matrices [25] and a modified Gaussian likelihood method. Bayesian hierarchical models have been published relevant to covariance/correlation matrix modeling where BCC and BCC heterogeneity can be further characterized based on posterior density of the quantities of interest [26–28]. In this paper, we focus on the family-type clustered design where subjects are from same units/families, as exemplified by the DIAN study. In our previous paper [29], BCCs have been defined under the framework of bivariate linear mixed effect (BLME) model, accompanied with statistical estimation and inferences to each type of BCCs in a family-type clustered design. Specifically, we have defined three BCCs: the family-level BCC ( ) accounts for the familial contribution to the biomarkers; the within-family subject level BCC ( ) accounts for individual subject level contribution when the familial effect is held constant; the overall marginal BCC ( ) encompasses contribution from both levels. Here, in consideration of subject heterogeneity, we extend our BCC definitions to estimate group-specific BCCs to examine whether BCCs estimated in a family-type clustered design differ by subject groups of interest, e.g. between mutation-carriers versus non-carriers in the DIAN study. We further make inference on the difference between group-specific BCCs by confidence intervals (CIs) and hypothesis testing.

Overall, our approach caters to the family type clustered design to estimate and make inference on BCCs. The method is rooted in the BLME framework and all the statistical inference is likelihood based. From the method, BCCs at all the levels can be derived and, further, we estimate and make direct inference (estimates, variance, hypothesis testing and confidence intervals) on the difference between the subject level BCCs. Under the maximum likelihood based inference, our method is able to use all data, including the families with only one subject and the subjects who have one of the paired measurements missing. These are two common issues in clustered study and are not handled by some methods requiring complete paired measurements such as Pearson correlation and the hidden correlation. Our approach, as shown later by simulations and real data analyses, performs well in the presence of these two real world issues.

Method

Defining BCCs

We first introduce the BLME framework under a two-level family-type design to define BCCs and group-specific BCCs of interest. The model can be easily generalized to designs of more than two levels. The term ‘family’ refers to the cluster/unit at the highest level and ‘subject’ refers to the lowest level throughout the paper. Denote the paired measurements of two variables (variable 1 and variable 2) collected on individual in family by . Let be the associated dichotomous group to which individual in family belongs, for instance, + vs. – can represent diseased vs. healthy, mutation carriers vs. mutation non-carriers. Assume a total of families are sampled and within a family , subjects are observed, i.e. and let be the total number of subjects across families. Let denote the known-by-design covariate vector which includes at least 1 for intercept and the group indicator while other subject characteristics (e.g. age, gender, education) can also be incorporated. Overall, encompasses three components including the fixed effects, the family random effect and the individual residual effect and can be naturally modeled by a BLME as the following,

| (1) |

is the associated regression coefficient vector of and is modeled as fixed effects. The variability in the biomarker measurements can be attributable to two main sources in a two-level family-type clustered design: the family and the individual. The familial contribution to of variable 1 and 2 accounting for heterogeneity in across families will be modeled by the random effect and , respectively. The bivariate family random effect is assumed to follow a bivariate normal distribution with a zero mean and a covariance matrix ,

where is the covariance between the two familial effects to account for correlation between the two variables when collected in the same family. Sharing by in all subjects from the same family induces a correlation in the measurements of variable (for ), reflecting the fact that measurements of a biomarker on the individuals from a same family are likely correlated since they share many characteristics (e.g. genetic, environment, diet). For different families, is independent of for . Therefore, the family-level BCC measuring the familial association between the two biomarkers is defined as,

| (2) |

with denoting correlation. A positive indicates that, for two biomarkers under analysis as a pair, the increase of familial contribution to one biomarker is associated with the increase of the familial contribution to the other biomarker.

Further, individual residual variability in accounts for variability that is beyond the family shared effect and attributable to each individual. Let denote the residual random effect, which is assumed to be independent of the family random effect . We hypothesize that individuals within a same family may exhibit some individual heterogeneity besides their familial common heterogeneity and this individual heterogeneity may depend on the associated group characteristics. To account for this, we assume the residual random effect will follow a bivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and a group-dependent covariance matrix as below,

where is the covariance between the paired measurements ( , ) of the two biomarkers on the same subject, presumably different between individuals in the positive and negative groups. As a result, the two biomarkers may show group-dependent heterogeneous correlation, with differing magnitudes or even opposite signs. The residuals of different subjects within the same families, i.e. and (for ), are independent of each other given the family random effect . across different families ( ). Hence, is the conditional covariance matrix of when conditioning on the family random effect and the group indicator ,

Naturally, given the family random effect, the group-specific within-family subject-level BCCs can be defined as,

| (3) |

Last, the marginal unconditional covariance matrix of encompasses both the within-family and between-family variance/covariance and thus will also be group-dependent,

Not differentiating between family – and individual-level variability, the overall marginal correlation between two biomarkers within each group can be described by the overall BCC ( ) as,

| (4) |

Statistical inference on the subject-level BCC (d=+,-) and their difference is the focus of this paper.

The regression coefficients and all parameters in the covariance matrices and ( ) are unknown and will be estimated from fitting the BLME (1). Under this BLME framework, we will be able to estimate the BCCs of the three types defined above and the difference between the group-specific BCCs at the within-family subject level and overall level.

BCC estimators and associated variances

To derive covariance, we organize all the variance and covariance parameters in the BLME (1) into vectors: , . The relevant parameters can be estimated via the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method as implemented in most statistical software such as SAS® (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R. Denote the REML estimators by and correspondingly. The estimators to the proposed BCCs can be subsequently estimated by replacing each relevant parameter by its REML estimator,

The difference on the group-specific BCCs at the within-family subject level and marginally can be subsequently estimated by and , respectively.

To make statistical inference, the variance on the estimators of each of the BCCs can be derived via the multivariate delta method,

where denotes any of the BCCs ( , , , and ), refers to the corresponding sample REML estimator, represents the vector of partial derivatives of with respect to each element in , denotes the asymptotic estimation on the covariance matrix of , and the prime denotes transpose. The estimator on the variance, denoted by , can be obtained by plugging in the REML estimation of the involved parameters. The partial derivatives are presented in Appendix.

For the purpose to compare between two group-specific BCCs at a level (here, versus and versus ), we need to derive the relevant covariance. Let , , , . The 2-by-2 covariance matrix on the estimator of and can be subsequently derived as,

With the details on the partial derivatives described in Appendix. The variance on the difference of the group-specific BCCs at the subject level and the overall marginal level can be subsequently derived as,

with the off-diagonal entries in and giving and , respectively.

Confidence intervals

We continue to construct confidence intervals for the proposed estimators. With the REML estimator (denoting the estimation to any of the BCCs) and the estimation on the asymptotic variance derived in the previous section, the simple asymptotic (SA) Wald confidence interval (CI) of any of the BCCs is given by

where is the quantile of a standard normal distribution. The SA confidence interval on the difference of the group-specific BCCs at the within-family subject level and the overall marginal level can be derived as,

respectively. The above SA Wald CIs on the difference of two BCCs are always symmetric around the REML estimations. However, the underlying true sampling distributions may be highly skewed and it usually requires large sample size and medium sized difference in BCCs for the SA CIs to provide sufficient nominal coverage. GY Zou [30] proposes a modified asymptotic (MA) CI by utilizing the relationship between the difference in the estimates of two correlation coefficients and their associated lower and upper CI limits. Following the MA approach, the lower and upper MA CI limit on , correspondingly labeled as and , can be calculated as,

The correlation can be easily derived from the covariance matrix . The MA CI limits on have exactly the same expressions but need to replace the subscript of ‘ ’ to ‘ ’ accordingly in the above equations.

Hypothesis testing

We conduct formal statistical tests to test a specific BCC or the difference between two BCCs. For a specific BCC or the group-specific BCC difference denoted by , we test the null hypothesis against , where c is a pre-specified constant, usually set as 0. With the REML estimators and their associated variance derived in the previous section, to test the null hypothesis, the Wald statistic: can be constructed where is an estimator to an individual BCC or the difference between BCCs, and the denominator uses the associated variance estimator to as previously described. Alternatively, hypothesis testing at a significance level α can also be conducted based on the associated CI of an estimator. There is no evidence to reject the null hypothesis if a CI crosses over the hypothesized value or otherwise is rejected. Utilizing a SA CI is equivalent to conducting the corresponding Wald test, whereas utilizing a MA CI may render different results from the SA CI (i.e. Wald test). We will conduct the hypothesis testing using both the Wald test (equivalently the SA CI) and the MA CI and evaluate their operating characteristics.

Real example: AD biomarker correlation in DIAN

We used the real-world DIAN study to evaluate the relationships between five well-established AD biomarkers. The motivating study of DIAN provides a unique opportunity to explore the relationships of a rich collection of biomarkers in prodromal individuals who are still cognitively normal but with distinct risk for future development of symptomatic AD. The DIAN data set (data freeze 4) has been described and analyzed previously [29]. Here, we analyzed the same data set to examine whether a pair of biomarkers shows a different relationship as gauged by BCCs in the mutation-positive individuals in comparison to the mutation-negative individuals and whether the difference is statistically significant from zero.

We chose to focus on the biomarkers which have been widely investigated in pathologically confirmed AD patients, including , total and phosphorylated tau at 181 measured in CSF (labeled as CSF-tau, CSF-ptau, respectively), and the PET PIB uptake in the temporal brain region and the gyrus rectus of the frontal brain region (labeled as PIB-temporal and PIB-gyrus) measuring deposition. A total of 190 individuals from 72 families were cognitively normal at enrollment with a Clinical Dementia Rating [31] score of 0 indicating no dementia. Eighty-three individuals were mutation carriers, 93 were mutation non-carriers, and mutation status of 14 individuals were missing at the time of data freeze. The per-family mutation rate varied from 0 to 1 with a mean of 0.475. The estimated age from expected symptom onset (EAO: the difference between the age of an individual at the time of biomarker assessment and the parent’s age of symptomatic onset of AD) [32] had a mean of 0.08 with a range of −1.29–2.31 years after being centered at its median and divided by interquartile range. The family size ranged from 1 to 19 with a median of 2. Approximately 47% of the families have a single individual, 21% have two individuals and 11% have three. The missing value percentages of the markers were around 18%∼19%. We performed formal hypotheses testing on the markers’ missing data mechanism using the function TestMCARNormality from the R package MissMech [33] (which implements Little’s multivariate normality test [34]) and the R package RBtest (which implements a regression based test), while both tests supported a missing completely at random mechanism for the markers under analyses (Little’s test P=0.254). We investigated whether a pair of the markers shows differing associations dependent on the mutation status in cognitively normal individuals in the DIAN study.

Each pair of the biomarkers was separately modeled by a BLME, incorporating the fixed effects of EAO (in continuous format), mutation status (positive vs. negative) and marker indicator (0 vs.1 indicating the two biomarkers analyzed as a pair), the random family effect and the error term with specifications of mutation status-specific covariance matrices. The detailed SAS PROC MIXED script is provided in the Appendix. Among the 10 pairs of the biomarkers, the REML algorithm converged for all but the pair of CSF_ptau and PIB_GYRUS (due to many missing values when the two paired up) and thus the BCC analysis results on this pair were not reported. REML estimates of the covariance parameters in the BLME were extracted to derive estimation and the associated variance on the BCCs and the difference between the BCCs. Quantile-quantile plots of the Studentized residuals output from SAS PROC MIXED were examined and showed approximate conformation to normality with some slight deviations at the two ends for some of the pairs. Results on the group-specific subject-level BCCs ( ) are displayed in Table 1, while the family level BCC ( ) and the group-specific overall BCCs ( ) are presented in Supplemental Table 1. CSF-tau and CSF-ptau are found to be highly correlated at all levels, regardless of mutation status. Their within-family subject-level BCC among mutation carriers and non-carriers were estimated to be and , respectively, both significantly different from and the resulting difference ( ) was not significantly different from based on the Wald test ( ) or by 95% MA CI . Their family level BCC ( ) was estimated as 0.8359 ( ), indicating significant familial contribution to the two biomarkers while the marginal overall BCC ( ) was estimated as and (Supplemental Table 1) in the mutation negative and positive individuals, both significantly different from zero. These observations agree with the fact that phosphorylated tau is a subset of total tau and they should be always in high agreement [35]. Indeed, when examining CSF-ptau and CSF-ptau each with other biomarkers (e.g. CSF_Aβ42, PIB_GYRUS), the two exhibited similar (same sign and similar magnitude) association with the other biomarkers. Thus, for within-subject BCC analysis, it probably suffices to examine either one of the two. Interestingly, CSF_Aβ42 and CSF_ptau exhibited a positive subject-level BCC ( ) among mutation non-carriers but a negative subject-level BCC ( ) among mutation carriers, both statistically significantly different from 0, leading to a large negative difference ( , , ) between mutation carriers and non-carriers. Similar subject-level BCCs were observed between the pair of CSF_Aβ42 and CSF_tau, yet statistically not significant likely due to a small valid sample size with many missing values when the two paired up. The negative correlation between Aβ42 and ptau (or tau) in pathologically diagnosed AD patients has been commonly acknowledged in the AD field [36,37]. In the mutation carriers, the two PIB PET biomarkers (PIB_TMP, PIB_GYRUS) were both negatively correlated with CSF_Aβ42, with the estimated subject level BCCs ( ) reaching nearly −0.7 (P=4.09E-19 and 4.19E-20, respectively), agreeing with AD researchers’ hypothesis of reduced CSF Aβ42 accompanied with increased deposition of Aβ42 in the plaques of brains in AD patients [3,38] . Although the estimates in the mutation non-carriers were not statistically different from 0, the difference between the two mutation statuses was estimated to be between PIB_TMP and CSF_Aβ42 and between PIB_GYRUS and CSF_Aβ42, suggesting significantly differing correlation of the two pairs of biomarkers by mutation status. A similar observation was previously noted in the literature (Figure 3C,D in [39]) with an obvious negative correlation in mutation carriers and nearly no correlation in mutation non-carriers between CSF_Aβ42 and PIB mean cortical Aβ42 deposition (across multiple brain regions including TMP and GYRUS) although the result was not confirmed by statistical testing. The two PIB PET biomarkers were also positively correlated at the subject level with CSF_tau among the mutation carriers, while the correlations were not significantly different from zero among the mutation non-carriers, indirectly reflecting the well-known inverse relationship between CSF_Aβ42 and CSF_tau or CSF_ptau in AD patients [2,3,40] and in mutation carriers as we have observed here. The similar BCC estimates observed on the two PIB PET biomarker regions with others suggested that the two brain regions may have similar amyloid deposition. For a sensitivity analysis, multiple imputations were conducted to impute the missing marker values in the DIAN data for 300 times, and BCCs were estimated for each imputed data sets with averaged estimates calculated and reported (Supplemental Table 2). Based on the results after missing data imputation, the conclusions regarding marker relationships within mutation carriers and non-carriers were basically similar to those based on the main results presented in Table 1. Findings on the overall BCC ( ) were similar to those on the subject level BCCs though correlation magnitudes were weaker (Supplemental Table 1). In summary, statistical analyses of the family-type clustered data in the DIAN study have indicated that CSF and imaging biomarkers are already correlated in mutation positive AD-asymptomatic participants with the same correlation directions as observed in AD symptomatic patients, while the biomarkers are not correlated much in mutation negative asymptomatic participants.

Table 1.

Estimation and comparison of subject-level BCCs in DIAN.

| Marker1 | Marker2 | Estimate (SE) | P* | Estimate (SE) | P* | Estimate (SE) | P* | 95% SA CI | 95% MA CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF_AB42 | CSF_tau | 0.4127 (0.3334) | 0.2158 | −0.5377 (0.5922) | 0.3639 | −0.9504 (0.9115) | 0.2971 | (−2.7368, 0.8361) | (−1.8045, 1.0784) |

| CSF_AB42 | CSF_ptau | 0.3565 (0.1265) | 0.0048 | −0.5348 (0.1044) | 2.98E-07 | −0.8913 (0.1644) | 5.91E-08 | (−1.2135, −0.5691) | (−1.1718, −0.5347) |

| CSF_AB42 | PIB_TMP | −0.0040 (0.1469) | 0.9783 | −0.6822 (0.0764) | 4.09E-19 | −0.6783 (0.1645) | 3.75E-05 | (−1.0007, −0.3558) | (−0.9828, −0.3482) |

| CSF_AB42 | PIB_GYRUS | −0.1516 (0.1499) | 0.3118 | −0.6876 (0.0749) | 4.19E-20 | −0.536 (0.1704) | 0.0017 | (−0.8699, −0.202) | (−0.8626, −0.2048) |

| CSF_tau | CSF_ptau | 0.6413 (0.0769) | 7.76E-17 | 0.7113 (0.0739) | 6.66E-22 | 0.0699 (0.1035) | 0.4990 | (−0.1328, 0.2727) | (−0.1415, 0.2753) |

| CSF_tau | PIB_TMP | −0.122 (0.1391) | 0.3806 | 0.3899 (0.1293) | 0.0026 | 0.5119 (0.1903) | 0.0071 | (0.1389, 0.8849) | (0.1205, 0.8519) |

| CSF_tau | PIB_GYRUS | −0.1739 (0.1374) | 0.2057 | 0.339 (0.1292) | 0.0087 | 0.5129 (0.1893) | 0.0067 | (0.1419, 0.8838) | (0.1241, 0.8511) |

| CSF_ptau | PIB_TMP | −0.0788 (0.1458) | 0.5887 | 0.6472 (0.0886) | 2.8E-13 | 0.7260 (0.1721) | 2.45E-05 | (0.3888, 1.0633) | (0.3706, 1.0354) |

| PIB_TMP | PIB_GYRUS | 0.5020 (0.1156) | 1.42E-05 | 0.9396 (0.0157) | 1.44E-38 | 0.4376 (0.1181) | 0.0002 | (0.2061, 0.6691) | (0.2384, 0.699) |

*Bold values indicate Bonferroni adjusted P<0.05.

The estimates and associated standard error (SE) on the within-family subject level BCC in mutation-negative ( ) and mutation-positive individuals ( ) and their difference are reported, with associated Wald test p-values testing the individual BCCs or the difference against 0. Both the 95% SA Wald CI and 95% MA CI are provided on the estimate to the difference.

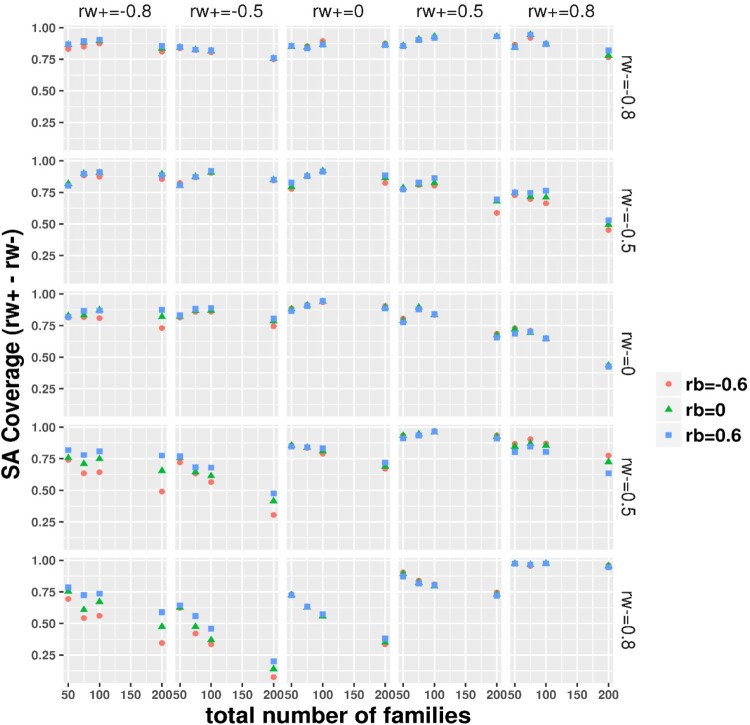

Figure 3.

Imbalance design: The simple asymptotic (SA) CI coverage evaluation for the group-specific subject level BCC difference , by the true value of the two group-specific BCC (at row) and (at column) and family-level BCC ( as indicated by color and symbol).

Simulation studies

Simulation design

We have previously assessed in simulations the proposed estimators to the individual BCCs under the impact of single family percentages and missing percentages [29]. Here, we focused on evaluating the statistical properties of the proposed estimators, the Wald test (i.e. SA CI) and MA CIs to the difference between the two subject-level BCCs. First, we started with an ideal balanced design with 200 families ( ) and a family size of 5 ( ). Next, we continued to simulate under an imbalanced design along a range of sample sizes and BCCs mimicking the real-world DIAN data set. Specifically, the total number of families varied with . The family sizes varied across families according to a negative binomial distribution (using the R function rnbinom) where the probability parameter was set at 0.08 and the size parameter at 0.5, as determined based on the averaged family size of 8 and standard deviation of 10.966 from the AD dataset. Family sizes which were simulated to be zero were reset as one, while families sizes above five were reset with equal probabilities to one or two to make the family size of one and two the two most abundant categories as in the DIAN dataset. The variance parameters were fixed at an , using the parameter estimates from the BLME fitting of the AD biomarkers pair CSF_AB42 and CSF_ptau as described in the real data analysis section. For the true values of BCCs, we employed the combinations of the subject-level BCC , the within-subject mutation positive BCC and the within-subject mutation negative BCC . The remaining covariance parameters can be derived from the above specifications. We assumed the mean structure of two markers as a linear function of mutation status and marker indicator. The number of mutation positive individuals per family was generated from a binomial distribution (using the R function rbinom) with a family’s simulated family size and a probability of 0.475 (the averaged per-family mutation rate in the AD dataset). The regression coefficients for the marker indicator variable and for the mutation status took the estimates for the two AD biomarkers (CSF_AB42 and CSF_ptau) as 0.16 and 0.14, respectively. A pair of markers’ values per family were finally independently simulated for all families according to Model (1) from a multivariate normal distribution with the calculated mean ( ) and the covariance matrix based on the specifications. 200 independent data sets were randomly generated for each simulation scenarios. The BLME model was fit to each simulated pair of markers to have REML estimates while the BCCs and the differences between two BCCs were subsequently derived with 95% SA and MA CI and Wald tests were conducted. Simulation results were evaluated for bias, root mean square error (RMSE), coverage of 95% SA and MA CI, and power (and type-I error rate) of the Wald test and using 95% MA CI.

For a sensitivity analysis on performance when two markers do not follow bivariate normal distribution, we simulated markers from a bivariate exponential distribution (which was generated from Gaussian Copula [41]), using the function rmvexp from the R package lcmix [42]. Note that the function rmvexp only takes a rate parameter (set as 1) and a correlation matrix (but not a covariance matrix). To accommodate this limitation, we had to fix all the variances and at 0.5 so that the diagonal covariance matrix per family is itself a correlation matrix with 1s at diagonal. All the other simulation settings remained the same as described above.

Simulation results

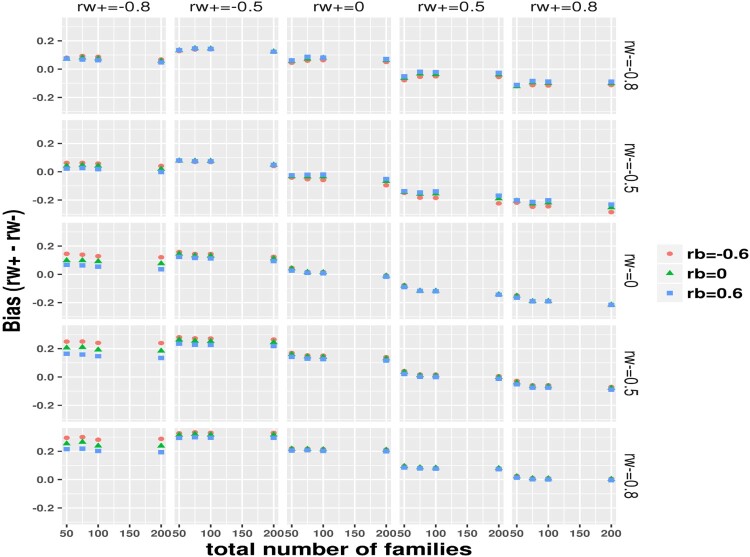

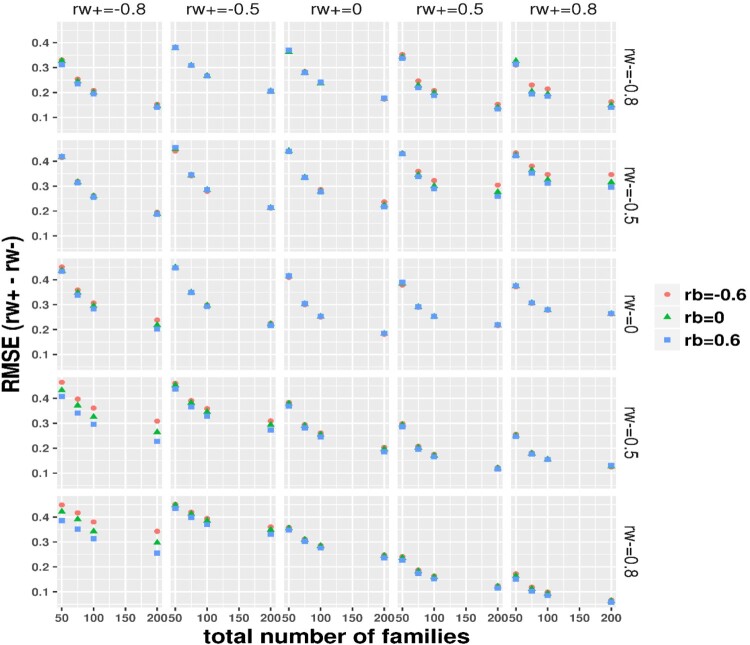

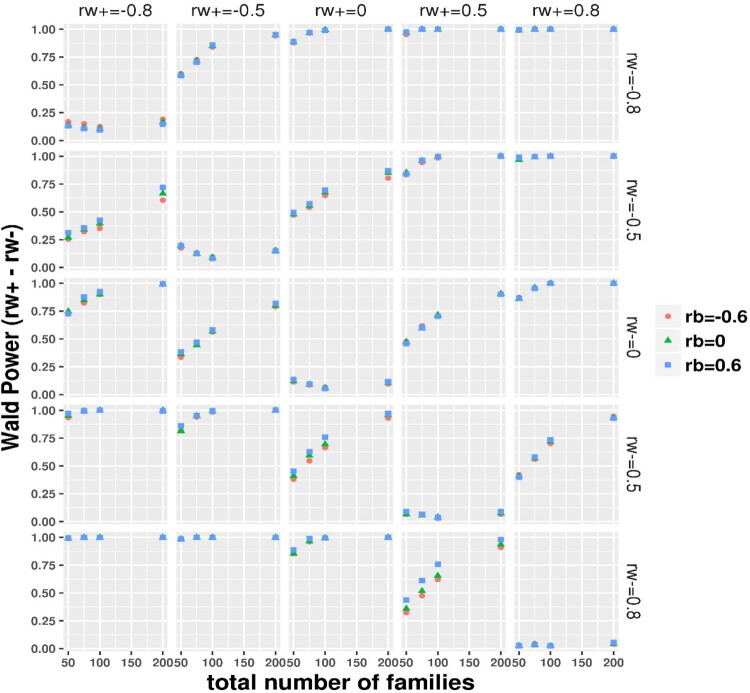

The simulation results under the ideal balance design with and are summarized in Table 2, showing expected asymptomatic performance including small bias, small RMSE and nearly nominal 95% coverage (power is sufficient at or nearly at 100% across scenarios, omitted due to space limit) on the difference between the subject-level BCCs. For simulations under the realistic small sample imbalance design, with the total number of families fixed at 50, 75, 100 and 200, the mean total number of simulated individuals was correspondingly around 86, 130, 173 and 348, that is, approximately 1.73 individuals per family. Thus, the total sample sizes were relatively small and a large proportion of families had a single individual as in the DIAN dataset. We focus on the difference between the within-family subject-level BCCs and evaluate the statistical properties under the realistic imbalance design as displayed in Figures 1–4 for bias, RMSE, coverage and power, respectively. As expected, the realistic imbalance design resulted in worse performance in comparison to the Table 2 results under the balanced design. Biases were generally larger when the true differences were of larger magnitudes. Across all panels, the biases were the largest above or around 0.2 at the combination panels of with . When the differences were truly zero (at the diagonal panels), biases trended toward zero with increasing total number of families though the biases were relatively larger under 0.1 when the two BCCs equaled at −0.8 and −0.5 than at 0, 0.5 and 0.8. Almost negligible influences from the family-level BCC were observed but at , biases obviously increased with moving from 0.6–0 to −0.6. RMSE decreased dramatically with total number of families from 50 to 200. The smallest RMSE were seen between 0∼0.2 at the right bottom combination panel of and . Crossing the row panels at or , the RMSE curves trended down toward zero as moved from along −0.8–0.8. Slightly higher RMSE with taking the value from 0.6–0 to −0.6 was similarly observed at the column panels of , as seen in the bias results. In most scenarios, the coverage varied between 75% and nearly 90%. When both subject-level BCCs were valued at 0.8 or 0.5, the coverage reached the 95% nominal level. The coverage was worst in the combination panels of or and where the coverage decreased with total number of families, probably because a greater proportion of single-individual families were simulated with more total families. The Figure 4 panels of a true difference of 0 gives the type-I error while others show power. The type-I error rates were smallest below 0.06 when both subject-level BCCs were of 0.8 and were around 0.1 when both were of 0.5 or 0, whereas the type-I error rate varied between 0.06∼0.23 when both were of −0.5 and −0.8. As expected, power increased with number of families and with increasing true differences. With 200 families, the Wald test showed approximately 75% power to nearly 100% power, which varied with the magnitude of true differences. The coverage of the 95% MA CI and the power of testing the difference being 0 in the null hypothesis using the 95% MA CI are plotted in Supplemental Figure 1 and 2, respectively. These results were nearly the same to the results using the 95% SA CIs (or Wald test). We further demonstrated that the within subject BCC and their difference estimated from our method are not impacted much by the two real world issues (many families having only 1 subject and many subjects missing one of the paired measurements) as commonly encountered in clustered studies. We simulated a complete dataset according to the settings previously described with 200 families and five subjects per family, we then operated on each simulated complete dataset to randomly select some percentage (=0% or 30%) of families to have only 1 subject or/and some percentage (=0% or 30%) of subjects to be missing one of the paired measurements and thus added four combination cases per simulation scenario: (0%/0%, 30%/0%, 0%/30% and 30%/30%) with the 0%/0% corresponding to the complete simulated data. The results from 200 per simulation scenario (see Supplemental File 1) showed that even under the influence of both issues affecting 30% families and subjects, we observed small biases, small RMSE and CIs with nice coverage for the within subject BCC estimates and the resultant difference estimates.

Table 2.

Simulation results under the balanced design with 200 families and a family size of 5.

| True parameters | rw- | rw+ | rw+ -rw- | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rb | rw- | rw+ | ro- | ro+ | rw+ - rw- | ro+ - ro- | Estimate | Bias | RMSE | Estimate | Bias | RMSE | Estimate | Bias | RMSE | SA CI coverage | Wald test size | MA CI coverage | MA CI size | SA CI length | MA CI length |

| −0.6 | −0.8 | −0.8 | −0.7559 | −0.7679 | 0 | −0.0120 | −0.7996 | 0.0004 | 0.0246 | −0.8025 | −0.0025 | 0.0249 | −0.0029 | −0.0029 | 0.0350 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.0978 | 0.0983 |

| −0.6 | −0.8 | −0.5 | −0.7559 | −0.4928 | 0.3 | 0.2631 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0251 | −0.5052 | −0.0052 | 0.0506 | 0.2943 | −0.0057 | 0.0563 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.1571 | 0.1573 |

| −0.6 | −0.8 | 0 | −0.7559 | −0.0342 | 0.8 | 0.7217 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0251 | −0.0071 | −0.0071 | 0.0674 | 0.7924 | −0.0076 | 0.0717 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2015 | 0.2011 |

| −0.6 | −0.8 | 0.5 | −0.7559 | 0.4243 | 1.3 | 1.1803 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0250 | 0.4946 | −0.0054 | 0.0516 | 1.2942 | −0.0058 | 0.0572 | 0.965 | 0.035 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1622 | 0.1622 |

| −0.6 | −0.8 | 0.8 | −0.7559 | 0.6995 | 1.6 | 1.4554 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0247 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0256 | 1.5969 | −0.0031 | 0.0357 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.1014 | 0.1017 |

| −0.6 | −0.5 | −0.8 | −0.4983 | −0.7679 | −0.3 | −0.2696 | −0.4997 | 0.0003 | 0.0500 | −0.8023 | −0.0023 | 0.0253 | −0.3027 | −0.0027 | 0.0555 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.1575 | 0.1577 |

| −0.6 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.4983 | −0.4928 | 0 | 0.0055 | −0.4994 | 0.0006 | 0.0510 | −0.5051 | −0.0051 | 0.0511 | −0.0057 | −0.0057 | 0.0713 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2003 | 0.2004 |

| −0.6 | −0.5 | 0 | −0.4983 | −0.0342 | 0.5 | 0.4640 | −0.4994 | 0.0006 | 0.0514 | −0.0070 | −0.0070 | 0.0677 | 0.4924 | −0.0076 | 0.0842 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.2369 | 0.2364 |

| −0.6 | −0.5 | 0.5 | −0.4983 | 0.4243 | 1 | 0.9226 | −0.4994 | 0.0006 | 0.0512 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0517 | 0.9941 | −0.0059 | 0.0723 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.2049 | 0.2047 |

| −0.6 | −0.5 | 0.8 | −0.4983 | 0.6995 | 1.3 | 1.1977 | −0.4994 | 0.0006 | 0.0507 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0256 | 1.2968 | −0.0032 | 0.0568 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.1615 | 0.1615 |

| −0.6 | 0 | −0.8 | −0.0688 | −0.7679 | −0.8 | −0.6991 | −0.0003 | −0.0003 | 0.0663 | −0.8022 | −0.0022 | 0.0256 | −0.8019 | −0.0019 | 0.0704 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.2006 | 0.2002 |

| −0.6 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.0688 | −0.4928 | −0.5 | −0.4240 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0674 | −0.5049 | −0.0049 | 0.0515 | −0.5048 | −0.0048 | 0.0834 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.2354 | 0.2350 |

| −0.6 | 0 | 0 | −0.0688 | −0.0342 | 0 | 0.0346 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0681 | −0.0068 | −0.0068 | 0.0679 | −0.0069 | −0.0069 | 0.0947 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.2670 | 0.2661 |

| −0.6 | 0 | 0.5 | −0.0688 | 0.4243 | 0.5 | 0.4932 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0678 | 0.4948 | −0.0052 | 0.0516 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0844 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2391 | 0.2386 |

| −0.6 | 0 | 0.8 | −0.0688 | 0.6995 | 0.8 | 0.7683 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0670 | 0.7975 | −0.0025 | 0.0255 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0714 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2031 | 0.2027 |

| −0.6 | 0.5 | −0.8 | 0.3606 | −0.7679 | −1.3 | −1.1285 | 0.4991 | −0.0009 | 0.0506 | −0.8021 | −0.0021 | 0.0256 | −1.3013 | −0.0013 | 0.0561 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1595 | 0.1595 |

| −0.6 | 0.5 | −0.5 | 0.3606 | −0.4928 | −1 | −0.8534 | 0.4994 | −0.0006 | 0.0511 | −0.5047 | −0.0047 | 0.0517 | −1.0040 | −0.0040 | 0.0714 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.2013 | 0.2011 |

| −0.6 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.3606 | −0.0342 | −0.5 | −0.3948 | 0.4995 | −0.0005 | 0.0517 | −0.0066 | −0.0066 | 0.0678 | −0.5061 | −0.0061 | 0.0838 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.2363 | 0.2358 |

| −0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3606 | 0.4243 | 0 | 0.0637 | 0.4995 | −0.0005 | 0.0515 | 0.4949 | −0.0051 | 0.0513 | −0.0046 | −0.0046 | 0.0719 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2037 | 0.2038 |

| −0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.3606 | 0.6995 | 0.3 | 0.3389 | 0.4995 | −0.0005 | 0.0508 | 0.7975 | −0.0025 | 0.0253 | 0.2980 | −0.0020 | 0.0564 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.1606 | 0.1608 |

| −0.6 | 0.8 | −0.8 | 0.6183 | −0.7679 | −1.6 | −1.3862 | 0.7994 | −0.0006 | 0.0247 | −0.8020 | −0.0020 | 0.0256 | −1.6014 | −0.0014 | 0.0351 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.0993 | 0.0996 |

| −0.6 | 0.8 | −0.5 | 0.6183 | −0.4928 | −1.3 | −1.1111 | 0.7994 | −0.0006 | 0.0249 | −0.5044 | −0.0044 | 0.0516 | −1.3038 | −0.0038 | 0.0564 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.1582 | 0.1582 |

| −0.6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.6183 | −0.0342 | −0.8 | −0.6525 | 0.7995 | −0.0005 | 0.0252 | −0.0063 | −0.0063 | 0.0674 | −0.8058 | −0.0058 | 0.0711 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1998 | 0.1994 |

| −0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6183 | 0.4243 | −0.3 | −0.1939 | 0.7996 | −0.0004 | 0.0253 | 0.4951 | −0.0049 | 0.0507 | −0.3045 | −0.0045 | 0.0561 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1586 | 0.1588 |

| −0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6183 | 0.6995 | 0 | 0.0812 | 0.7996 | −0.0004 | 0.0249 | 0.7976 | −0.0024 | 0.0248 | −0.0021 | −0.0021 | 0.0351 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1000 | 0.1005 |

| 0 | −0.8 | −0.8 | −0.6871 | −0.7337 | 0 | −0.0466 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0248 | −0.8025 | −0.0025 | 0.0250 | −0.0030 | −0.0030 | 0.0355 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.0994 | 0.1000 |

| 0 | −0.8 | −0.5 | −0.6871 | −0.4586 | 0.3 | 0.2285 | −0.7994 | 0.0006 | 0.0252 | −0.5052 | −0.0052 | 0.0508 | 0.2942 | −0.0058 | 0.0567 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.1577 | 0.1579 |

| 0 | −0.8 | 0 | −0.6871 | 0.0000 | 0.8 | 0.6871 | −0.7994 | 0.0006 | 0.0252 | −0.0070 | −0.0070 | 0.0674 | 0.7924 | −0.0076 | 0.0718 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.2012 | 0.2008 |

| 0 | −0.8 | 0.5 | −0.6871 | 0.4586 | 1.3 | 1.1457 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0251 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0515 | 1.2941 | −0.0059 | 0.0572 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1615 | 0.1615 |

| 0 | −0.8 | 0.8 | −0.6871 | 0.7337 | 1.6 | 1.4208 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0249 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0255 | 1.5969 | −0.0031 | 0.0358 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.1014 | 0.1017 |

| 0 | −0.5 | −0.8 | −0.4294 | −0.7337 | −0.3 | −0.3043 | −0.4996 | 0.0004 | 0.0503 | −0.8024 | −0.0024 | 0.0254 | −0.3029 | −0.0029 | 0.0563 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.1596 | 0.1598 |

| 0 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.4294 | −0.4586 | 0 | −0.0291 | −0.4993 | 0.0007 | 0.0513 | −0.5052 | −0.0052 | 0.0513 | −0.0059 | −0.0059 | 0.0721 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2023 | 0.2023 |

| 0 | −0.5 | 0 | −0.4294 | 0.0000 | 0.5 | 0.4294 | −0.4993 | 0.0007 | 0.0517 | −0.0071 | −0.0071 | 0.0678 | 0.4922 | −0.0078 | 0.0846 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2376 | 0.2372 |

| 0 | −0.5 | 0.5 | −0.4294 | 0.4586 | 1 | 0.8880 | −0.4993 | 0.0007 | 0.0514 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0516 | 0.9940 | −0.0060 | 0.0724 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.2046 | 0.2045 |

| 0 | −0.5 | 0.8 | −0.4294 | 0.7337 | 1.3 | 1.1631 | −0.4993 | 0.0007 | 0.0509 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0256 | 1.2968 | −0.0033 | 0.0568 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.1613 | 0.1614 |

| 0 | 0 | −0.8 | 0.0000 | −0.7337 | −0.8 | −0.7337 | −0.0003 | −0.0003 | 0.0666 | −0.8023 | −0.0023 | 0.0257 | −0.8021 | −0.0021 | 0.0710 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.2024 | 0.2020 |

| 0 | 0 | −0.5 | 0.0000 | −0.4586 | −0.5 | −0.4586 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0676 | −0.5050 | −0.0050 | 0.0518 | −0.5051 | −0.0051 | 0.0842 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.2375 | 0.2371 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0682 | −0.0069 | −0.0069 | 0.0681 | −0.0071 | −0.0071 | 0.0951 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.2679 | 0.2671 |

| 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.0000 | 0.4586 | 0.5 | 0.4586 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0679 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0516 | 0.4946 | −0.0054 | 0.0844 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.2388 | 0.2383 |

| 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.0000 | 0.7337 | 0.8 | 0.7337 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0670 | 0.7975 | −0.0025 | 0.0255 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0714 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2028 | 0.2025 |

| 0 | 0.5 | −0.8 | 0.4294 | −0.7337 | −1.3 | −1.1631 | 0.4992 | −0.0008 | 0.0507 | −0.8023 | −0.0023 | 0.0258 | −1.3014 | −0.0014 | 0.0565 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.1607 | 0.1607 |

| 0 | 0.5 | −0.5 | 0.4294 | −0.4586 | −1 | −0.8880 | 0.4995 | −0.0006 | 0.0513 | −0.5048 | −0.0048 | 0.0520 | −1.0043 | −0.0043 | 0.0720 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.2031 | 0.2029 |

| 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.4294 | 0.0000 | −0.5 | −0.4294 | 0.4996 | −0.0004 | 0.0517 | −0.0068 | −0.0068 | 0.0681 | −0.5064 | −0.0064 | 0.0843 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2374 | 0.2369 |

| 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4294 | 0.4586 | 0 | 0.0291 | 0.4996 | −0.0004 | 0.0515 | 0.4948 | −0.0052 | 0.0514 | −0.0048 | −0.0048 | 0.0719 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2035 | 0.2036 |

| 0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4294 | 0.7337 | 0.3 | 0.3043 | 0.4995 | −0.0005 | 0.0507 | 0.7975 | −0.0025 | 0.0253 | 0.2979 | −0.0021 | 0.0563 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1602 | 0.1604 |

| 0 | 0.8 | −0.8 | 0.6871 | −0.7337 | −1.6 | −1.4208 | 0.7994 | −0.0006 | 0.0248 | −0.8022 | −0.0022 | 0.0257 | −1.6016 | −0.0016 | 0.0354 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.1003 | 0.1006 |

| 0 | 0.8 | −0.5 | 0.6871 | −0.4586 | −1.3 | −1.1457 | 0.7995 | −0.0005 | 0.0250 | −0.5046 | −0.0046 | 0.0519 | −1.3041 | −0.0041 | 0.0569 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.1597 | 0.1597 |

| 0 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.6871 | 0.0000 | −0.8 | −0.6871 | 0.7996 | −0.0004 | 0.0252 | −0.0065 | −0.0065 | 0.0678 | −0.8061 | −0.0061 | 0.0716 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.2011 | 0.2007 |

| 0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6871 | 0.4586 | −0.3 | −0.2285 | 0.7996 | −0.0004 | 0.0252 | 0.4950 | −0.0050 | 0.0509 | −0.3046 | −0.0046 | 0.0564 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.1592 | 0.1594 |

| 0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6871 | 0.7337 | 0 | 0.0466 | 0.7996 | −0.0004 | 0.0249 | 0.7976 | −0.0024 | 0.0249 | −0.0021 | −0.0021 | 0.0351 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.0999 | 0.1005 |

| 0.6 | −0.8 | −0.8 | −0.6183 | −0.6995 | 0 | −0.0812 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0249 | −0.8025 | −0.0025 | 0.0250 | −0.0030 | −0.0030 | 0.0356 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.0991 | 0.0997 |

| 0.6 | −0.8 | −0.5 | −0.6183 | −0.4243 | 0.3 | 0.1939 | −0.7994 | 0.0006 | 0.0252 | −0.5052 | −0.0052 | 0.0507 | 0.2942 | −0.0058 | 0.0567 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.1571 | 0.1573 |

| 0.6 | −0.8 | 0 | −0.6183 | 0.0342 | 0.8 | 0.6525 | −0.7994 | 0.0006 | 0.0253 | −0.0070 | −0.0070 | 0.0672 | 0.7924 | −0.0076 | 0.0716 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.2001 | 0.1997 |

| 0.6 | −0.8 | 0.5 | −0.6183 | 0.4928 | 1.3 | 1.1111 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0250 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0512 | 1.2942 | −0.0058 | 0.0568 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.1600 | 0.1600 |

| 0.6 | −0.8 | 0.8 | −0.6183 | 0.7679 | 1.6 | 1.3862 | −0.7995 | 0.0005 | 0.0249 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0254 | 1.5969 | −0.0031 | 0.0355 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1005 | 0.1008 |

| 0.6 | −0.5 | −0.8 | −0.3606 | −0.6995 | −0.3 | −0.3389 | −0.4995 | 0.0005 | 0.0503 | −0.8025 | −0.0025 | 0.0255 | −0.3030 | −0.0030 | 0.0564 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.1599 | 0.1601 |

| 0.6 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.3606 | −0.4243 | 0 | −0.0637 | −0.4992 | 0.0008 | 0.0513 | −0.5053 | −0.0053 | 0.0514 | −0.0060 | −0.0060 | 0.0723 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2025 | 0.2026 |

| 0.6 | −0.5 | 0 | −0.3606 | 0.0342 | 0.5 | 0.3948 | −0.4992 | 0.0008 | 0.0516 | −0.0071 | −0.0071 | 0.0677 | 0.4921 | −0.0079 | 0.0845 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.2366 | 0.2361 |

| 0.6 | −0.5 | 0.5 | −0.3606 | 0.4928 | 1 | 0.8534 | −0.4993 | 0.0007 | 0.0513 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0514 | 0.9940 | −0.0060 | 0.0719 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.2029 | 0.2028 |

| 0.6 | −0.5 | 0.8 | −0.3606 | 0.7679 | 1.3 | 1.1285 | −0.4994 | 0.0006 | 0.0508 | 0.7974 | −0.0026 | 0.0254 | 1.2968 | −0.0032 | 0.0565 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.1603 | 0.1603 |

| 0.6 | 0 | −0.8 | 0.0688 | −0.6995 | −0.8 | −0.7683 | −0.0002 | −0.0002 | 0.0666 | −0.8024 | −0.0024 | 0.0257 | −0.8022 | −0.0022 | 0.0711 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2027 | 0.2024 |

| 0.6 | 0 | −0.5 | 0.0688 | −0.4243 | −0.5 | −0.4932 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0677 | −0.5052 | −0.0052 | 0.0519 | −0.5053 | −0.0053 | 0.0844 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.2379 | 0.2375 |

| 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.0688 | 0.0342 | 0 | −0.0346 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0681 | −0.0071 | −0.0071 | 0.0680 | −0.0073 | −0.0073 | 0.0950 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.2670 | 0.2662 |

| 0.6 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.0688 | 0.4928 | 0.5 | 0.4240 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0676 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0514 | 0.4946 | −0.0054 | 0.0838 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2368 | 0.2363 |

| 0.6 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.0688 | 0.7679 | 0.8 | 0.6991 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0667 | 0.7975 | −0.0025 | 0.0253 | 0.7975 | −0.0025 | 0.0708 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.2011 | 0.2007 |

| 0.6 | 0.5 | −0.8 | 0.4983 | −0.6995 | −1.3 | −1.1977 | 0.4992 | −0.0008 | 0.0506 | −0.8024 | −0.0024 | 0.0258 | −1.3016 | −0.0016 | 0.0564 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.1607 | 0.1607 |

| 0.6 | 0.5 | −0.5 | 0.4983 | −0.4243 | −1 | −0.9226 | 0.4995 | −0.0005 | 0.0512 | −0.5050 | −0.0050 | 0.0521 | −1.0046 | −0.0046 | 0.0722 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.955 | 0.045 | 0.2034 | 0.2032 |

| 0.6 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.4983 | 0.0342 | −0.5 | −0.4640 | 0.4997 | −0.0003 | 0.0516 | −0.0070 | −0.0070 | 0.0681 | −0.5066 | −0.0066 | 0.0843 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.935 | 0.065 | 0.2369 | 0.2364 |

| 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4983 | 0.4928 | 0 | −0.0055 | 0.4996 | −0.0004 | 0.0512 | 0.4947 | −0.0053 | 0.0513 | −0.0049 | −0.0049 | 0.0714 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.2017 | 0.2018 |

| 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4983 | 0.7679 | 0.3 | 0.2696 | 0.4995 | −0.0005 | 0.0503 | 0.7975 | −0.0025 | 0.0251 | 0.2980 | −0.0020 | 0.0557 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.1582 | 0.1584 |

| 0.6 | 0.8 | −0.8 | 0.7559 | −0.6995 | −1.6 | −1.4554 | 0.7994 | −0.0006 | 0.0247 | −0.8023 | −0.0023 | 0.0258 | −1.6017 | −0.0017 | 0.0354 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.1004 | 0.1007 |

| 0.6 | 0.8 | −0.5 | 0.7559 | −0.4243 | −1.3 | −1.1803 | 0.7995 | −0.0005 | 0.0250 | −0.5049 | −0.0049 | 0.0521 | −1.3044 | −0.0044 | 0.0572 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1603 | 0.1603 |

| 0.6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.7559 | 0.0342 | −0.8 | −0.7217 | 0.7996 | −0.0004 | 0.0252 | −0.0067 | −0.0067 | 0.0680 | −0.8064 | −0.0064 | 0.0719 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.2014 | 0.2011 |

| 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7559 | 0.4928 | −0.3 | −0.2631 | 0.7997 | −0.0003 | 0.0251 | 0.4949 | −0.0051 | 0.0510 | −0.3048 | −0.0048 | 0.0563 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.1587 | 0.1589 |

| 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7559 | 0.7679 | 0 | 0.0120 | 0.7996 | −0.0004 | 0.0248 | 0.7976 | −0.0024 | 0.0249 | −0.0021 | −0.0021 | 0.0348 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.945 | 0.055 | 0.0989 | 0.0994 |

Figure 1.

Imbalance design: bias evaluation on the estimate to the group-specific subject level BCC difference , by the true value of the two group-specific BCC (at row) and (at column) and family-level BCC ( as indicated by color and symbol).

Figure 2.

Imbalance design: RMSE evaluation on the estimate to the group-specific subject level BCC difference , by the true value of the two group-specific BCC (at row) and (at column) and family-level BCC ( as indicated by color and symbol).

Figure 4.

Imbalance design: the power (type-I error rate at panels of a zero true difference) of the Wald test on , for the group-specific subject level BCC difference , by the true value of the two group-specific BCC (at row) and (at column) and family-level BCC ( as indicated by color and symbol).

Simulation results on the group-specific within family subject level BCC difference under bivariate exponential were shown in supplemental Figure 3–5 for bias, RMSE and Wald test power/type-I error rate, respectively. Overall, biases and RMSEs were comparatively larger than from the bivariate normal simulations when the true differences were large but biases remained small when the true difference was zero at diagonal panels. Type-I error rate when the true difference was zero varied around 0.1. Power reduced dramatically in most combination panels, though not much when the differences were large. Influences from the family-level BCC seemed more obvious.

Bear in mind that these simulation results mimicked the real-world applications with relatively small sample sizes and an imbalanced design with a very large proportion of single-individual families. As expected, the performance was worse than ideal scenarios but still acceptable.

Statistical software

PROC MIXED in the statistical software SAS® (version 9.4, SAS institute, Cary, NC) was used for the BLME fitting on the AD markers to derive all the BLME model parameters and SAS code is provided in the appendix. The statistical programming language R [43] (version 3.3.1) was used for all the other computations including data generation, estimate and 95% CI derivation, statistical testing and graph generation. All tests are two sided unless otherwise noted.

Discussion

BCCs and group-specific BCCs are scientifically important to understand relationship among biomarkers reflecting disease processes. Motivated by the AD DIAN study that the relationship between two biomarkers may depend on the presence or absence of gene mutations, we have accounted for subject group heterogeneity and defined BCCs and group-specific BCCs individually to gauge BCC differences between two biomarkers at subject level and overall level in family-type clustered studies. Our approach extended the original research rooted in BLME which has demonstrated great performance under unbalanced family size and missing data that are frequently observed in clustered studies [29]. Directly estimating and comparing BCCs provide a straightforward way to evaluate group-dependent heterogeneous association between two biomarkers and this is the focus of the paper. To provide formal statistical evidence that two biomarkers relate to each other in a different way dependent on subject group (e.g. mutation positive versus mutation negative, diseased vs. healthy), we have derived estimates to the difference of the group-specific BCCs, constructed SA and MA CIs, and conducted Wald test. Simulations under an ideal design proves the asymptomatic behavior while performance under an imbalanced design mimicking real-world data are worse as expected but still acceptable. By BCC analysis of the five AD biomarkers in the real-world DIAN data, we found that the biomarkers are significantly correlated based on the BCCs in mutation carriers (similar as observed in pathologically confirmed AD patients), but mostly not so in the mutation non-carriers. These results are scientifically important to help understand relationships among biomarkers in prodromal asymptomatic participants in the AD field.

We have focused on joint modeling of two continuous variables in the linear mixed effects model frame, although the methodology is readily extendable to three of more variables. Instead of fitting multiple pairwise BLME, multivariate linear mixed models are ideal to simultaneously modeling all continuous markers to derive the pairwise BCCs or group-specific BCCs of interest. This usually requires a sufficiently large valid pairwise sample size in order to estimate the many covariance parameters and thus may fail in analyzing real data sets with a small sample size under the presence of many missing values. The proposed approach is likelihood based and thus will use all the data, including those with one of the paired observations missing. Our approach performs well in presence of missing data (when the missing data mechanism is missing complete at random or missing at random) based on simulations and real data analyses. However, sensitivity analyses are still recommended to compare BCC estimations to the results with missing data imputed. In presence of missing not at random in data, the specific missing data mechanism need to be modeled as a component of the modeling framework. Normality is underlying the BLME. Model goodness-of-fit and parameter estimation accuracy and precision will be affected by deviation from the multivariate normal assumption, although BLME have been shown in statistical literature to be robust to moderate deviations from normality. We also examined the quantile-quantile plots of the residuals for large violations. For markers following very skewed distributions, the proposed BLME may not work well. Either parametric models tailored to skewed distributions or nonparametric type of estimation to the BCCs will have to be employed but the methods remain to be developed. In the BLME framework, NM Bello, JP Steibel and RJ Tempelman [44] have modeled a continuous variable and a binary variable jointly by augmenting the binary variables with an underlying Gaussian variable. Moreover, variance/covariance heterogeneous association at both family-level and subject level can be further interrogated by modeling unconstrained reparametrized variance/covariance parameters as functions of covariates (e.g. mutation status) and random effects. This is beyond the scope of this paper but readers interested in this line of research are referred to the relevant references [25,45].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Genetics Core (Alison Goate, DPhil, Core Leader) of the DIAN (UF1 AG03243807) for the genetic data, Biomarker Core (Anne Fagan, PhD, Core leader) for the CSF data, and Imaging Core (Tammie Benzinger, MD, PhD, Core leader) for the imaging data. J Luo and CX conceptualized the paper and designed the study. JL performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. J Lu and Chen helped with missing data analyses. GW, AF, GD, JV contributed to DIAN data. All authors participated in discussion, reviewed and revised the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Appendix.

Partial derivatives of BCCs with respect to relevant parameters

The matrix of the partial derivatives of with respect to each component in and with respect to each component in can be written out specifically as the following,

For , the three associated partial derivatives have exactly the same expressions as the above three partial derivatives of with respect to , thus we only need to substitute , simultaneously by , correspondingly to obtain .

we have,

we have,

while the other six components have the same expression as their counterparts in above but need to substitute the ‘-’ to ‘+’.

SAS code for practical implementation of the BLME

Specifically, the DIAN family-type clustered data on two biomarkers under analysis as a pair to be correlated were organized into a long and tall structure. The variable ‘family’ stores unique family identifiers, ‘subject’ stores unique individual identifier within each family, ‘Y’ stores the measurements of the measurements of the two biomarkers stacked together and importantly, the indicator variable ‘marker’ of values 0 and 1 represents biomarker 1 and 2 respectively. The ‘EAO’ variable gives the estimate age of onset for each subject. ‘MUTATION’ gives the mutation status of being positive or negative. As shown in the following detailed SAS coding (assuming no other covariates), ‘Y’ is modeled with ‘marker’ as a fixed effect in the ‘model’ statement, also as a random effect at the family level in the ‘random’ statement, as well as a random effect in the ‘repeated’ statement as the two variables are repeatedly measured on each subject within each family:

PROC MIXED data = dian method = reml asycorr asycov;

CLASS family subject marker MUTATION;

MODEL Y = MUTATION EAO marker/e s residual;

RANDOM marker /solution type = UN subject = family g gcorr;

REPEATED marker /type = UN subject = subject (family) group = MUTATION r rcorr;

RUN;

The implementation of the above SAS script will provide estimates to all the relevant parameters from the BLME. Other fixed effects can be readily added to the ‘Model’ statement in the above SAS script to further adjust for other important covariates. Thereafter, all the proposed BCCs and BCC differences were derived in R (http://cran.r-project.org). The scripts can be requested by contacting the authors.

Funding Statement

This study was partly supported by National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA91842 (Dr. Eberlein), U10 CA180860 (Dr. Mutch/Dr. Ellis/Dr. Luo), National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant UF1 AG03243807 (Dr Bateman) and P50 AG005681 (Dr. Morris), NIA R01 AG034119 (Dr. Xiong).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Availability of data and materials

The simulation and real data analysis programming codes will be available at request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

AMF has received research funding from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, Biogen, Centene, Fujirebio and Roche Diagnostics. She is a member of the scientific advisory boards for Roche Diagnostics, Genentech and AbbVie and also consults for Araclon/Grifols, Diadem, and DiamiR. There are no conflicts. GSD is supported by a career development grant from the NIH (K23AG064029). He owns stock (>$10,000) in ANI Pharmaceuticals (a generic pharmaceutical company). He serves as a topic editor for DynaMed (EBSCO), overseeing development of evidence-based educational content, and as the Clinical Director of the Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis Foundation (Inc, Canada; uncompensated). All the authors declare no competing interests related to this work.

Ethics approval and consent to the participant

The use of the DIAN observational study data was approved by the DIAN Steering Committee for data analysis and publication.

References

- 1.Humpel C., Identifying and validating biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Trends Biotechnol. 29(1) (2011), pp. 26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blennow K., Zetterberg H., and Fagan A.M., Fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Med. 2(9) (2012), pp. a006221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagan A.M., Mintun M.A., Mach R.H., Lee S.Y., Dence C.S., Shah A.R., LaRossa G.N., Spinner M.L., Klunk W.E., Mathis C.A., et al. , Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann. Neurol. 59(3) (2006), pp. 512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang J.H., Korecka M., Toledo J.B., Trojanowski J.Q., and Shaw L.M., Clinical utility and analytical challenges in measurement of cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta(1-42) and tau proteins as Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Clin. Chem. 59(6) (2013), pp. 903–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saint-Aubert L., Lemoine L., Chiotis K., Leuzy A., Rodriguez-Vieitez E., and Nordberg A., Tau PET imaging: present and future directions. Mol. Neurodegener. 12(1) (2017), pp. 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattsson N., Insel P.S., Landau S., Jagust W., Donohue M., Shaw L.M., Trojanowski J.Q., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., Weiner M., et al. , Diagnostic accuracy of CSF Ab42 and florbetapir PET for Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 1(8) (2014), pp. 534–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babic M., Svob Strac D., Muck-Seler D., Pivac N., Stanic G., Hof P.R., and Simic G., Update on the core and developing cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. Croat. Med. J. 55(4) (2014), pp. 347–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbeek M.M., and Olde Rikkert M.G.,: cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the evaluation of Alzheimer disease. Clin. Chem. 54(10) (2008), pp. 1589–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galasko D., Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: a fractional improvement? Arch. Neurol. 60(9) (2003), pp. 1195–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blennow K., Dubois B., Fagan A.M., Lewczuk P., de Leon M.J., and Hampel H., Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the diagnosis of early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers. Dement. 11(1) (2015), pp. 58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmqvist S., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., Vestberg S., Andreasson U., Brooks D.J., Owenius R., Hagerstrom D., Wollmer P., Minthon L., et al. , Accuracy of brain amyloid detection in clinical practice using cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid 42: a cross-validation study against amyloid positron emission tomography. JAMA. Neurol. 71(10) (2014), pp. 1282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jagust W.J., Landau S.M., Shaw L.M., Trojanowski J.Q., Koeppe R.A., Reiman E.M., Foster N.L., Petersen R.C., Weiner M.W., Price J.C., et al. , Relationships between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology 73(15) (2009), pp. 1193–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaffer J.L., Petrella J.R., Sheldon F.C., Choudhury K.R., Calhoun V.D., Coleman R.E., and Doraiswamy P.M., Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging I: predicting cognitive decline in subjects at risk for Alzheimer disease by using combined cerebrospinal fluid, MR imaging, and PET biomarkers. Radiology 266(2) (2013), pp. 583–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pouliot Y., Gao J., Su Q.J., Liu G.G., and Ling X.B., DIAN: a novel algorithm for genome ontological classification. Genome Res. 11(10) (2001), pp. 1766–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimada H., [The DIAN study]. Brain Nerve 65(10) (2013), pp. 1179–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Storandt M., Balota D.A., Aschenbrenner A.J., and Morris J.C., Clinical and psychological characteristics of the initial cohort of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN). Neuropsychology 28(1) (2014), pp. 19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudo T., Iqbal K., Ravid R., Swaab D.F., and Grundke-Iqbal I., Alzheimer disease: correlation of cerebro-spinal fluid and brain ubiquitin levels. Brain Res. 639(1) (1994), pp. 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skillback T., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., and Mattsson N., Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease and subcortical axonal damage in 5,542 clinical samples. Alzheimers. Res. Ther. 5(5) (2013), pp. 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bland J.M., and Altman D.G., Calculating correlation coefficients with repeated observations: part 1–correlation within subjects. Br. Med. J. 310 (1995), pp. 446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bland J.M., and Altman D.G., Calculating correlation coefficients with repeated observations: part 2–correlation between subjects. Br. Med. J. 310 (1995), pp. 633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao F., Thompson P., Xiong C., and Miller J.P., Analyzing multivariate longitudinal data using SAS®. In: Thirty-first Annual SAS Users Group International Conference: 2006: SAS; 2006.

- 22.Roy A., Estimating correlation coefficient between two variables with repeated observations using mixed effects model. Biom. J. 48(2) (2006), pp. 286–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen T., and Jiang J., Simple estimation of hidden correlation in repeated measures. Stat. Med. 30(29) (2011), pp. 3403–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AI-Rawwash M., and Pourahmadi M., Gaussian estimation and joint modeling of dispersions and correlations in longitudinal data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 82(2) (2006), pp. 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purahmadi M., Joint mean-covariance models with applications to longitudinal data: unconstrained parameterisation. Biometrika 86(3) (1999), pp. 677–690. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liechty J.C., Liechty M.W., and Müller P., Bayesian correlation estimation. BIOMETRIKA 91(1) (2004), pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai B., and Dunson D.B., Bayesian covariance selection in generalized linear mixed models. Biometrics 62(2) (2006), pp. 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinney S.K., and Dunson D.B., Fixed and random effects selection in linear and logistic models. Biometrics 63(3) (2007), pp. 690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo J., D'Angela G., Gao F., Ding J., and Xiong C., Bivariate correlation coefficients in family-type clustered studies. Biom. J. 57(6) (2015), pp. 1084–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zou G.Y., Toward using confidence intervals to compare correlations. Psychol. Methods 12(4) (2007), pp. 399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris J.C., The clinical Dementia Rating (Cdr) - current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43(11) (1993), pp. 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bateman R.J., Xiong C., Benzinger T.L., Fagan A.M., Goate A., Fox N.C., Marcus D.S., Cairns N.J., Xie X., Blazey T.M., et al. , Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 367(9) (2012), pp. 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamshidian M., Jalal S., and Jansen C., Missmech: An R package for testing homoscedasticity, multivariate normality, and Missing Completely at random (MCAR). J. Stat. Softw. 56(6) (2014), pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Little R.J.A., A test of missing Completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83(404) (1988), pp. 1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fagan A.M., Mintun M.A., Shah A.R., Aldea P., Roe C.M., Mach R.H., Marcus D., and Morris J.C., Holtzman DM: cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO. Mol. Med. 1(8-9) (2009), pp. 371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glosová L H., Koukolík J., Bojar F., and and Škoda M., D: assessment of total tau protein, phospho tau and beta amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative disorders, an autopsy correlation study. Klin Biochem Metab 14(35) (2006), pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sjogren M., Davidsson P., Tullberg M., Minthon L., Wallin A., Wikkelso C., Granerus A.K., Vanderstichele H., and Vanmechelen E., Blennow k: both total and phosphorylated tau are increased in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosur Ps 70(5) (2001), pp. 624–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blennow K., Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. NeuroRx. 1(2) (2004), pp. 213–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fagan A.M., Xiong C., Jasielec M.S., Bateman R.J., Goate A.M., Benzinger T.L., Ghetti B., Martins R.N., Masters C.L., Mayeux R., et al. , Longitudinal change in CSF biomarkers in autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 6(226) (2014), pp. 226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forsberg A., Engler H., Almkvist O., Blomquist G., Hagman G., Wall A., Ringheim A., Langstrom B., and Nordberg A., PET imaging of amyloid deposition in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 29(10) (2008), pp. 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song P.X.K., Multivariate dispersion models generated from Gaussian copula. Scand J Stat 27(2) (2000), pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dvorkin D., lcmix:layered and chained mixture models. In: R package. 0.3 edn. R; 2012.

- 43.R Core Team : R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In. Vienna, Australia: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017.

- 44.Bello N.M., Steibel J.P., and Tempelman R.J., Hierarchical Bayesian modeling of heterogeneous cluster- and subject-level associations between continuous and binary outcomes in dairy production. Biom. J. 54(2) (2012), pp. 230–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Rawwash M., and Pourahmadi M., Gaussian estimation and joint modeling of dispersions and correlations in longitudinal data. Comput Meth Prog Bio 82(2) (2006), pp. 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The simulation and real data analysis programming codes will be available at request from the corresponding author.