Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to examine consumer knowledge of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) levels for usual cannabis products.

Methods:

Data are from the International Cannabis Policy Study conducted online in August–September 2018. Respondents included 6471 past 12-month cannabis users, aged 16–65 years, recruited from the Nielsen Global Insights Consumer Panel using nonprobability methods. Respondents were recruited from Canada, which had not yet legalized nonmedical cannabis (n=2354), and US states that had (n=2160) and had not (n=1957) legalized nonmedical cannabis.

Results:

Participants reported descriptive THC:CBD ratios (e.g., high THC, low CBD) and numeric THC and CBD levels (mg or %) for products they usually use in each of nine product categories. Few consumers knew and were able to report the numeric THC or CBD levels of their usual cannabis products. For example, only 10% of dried herb consumers reported the THC level, approximately 30% of whom reported implausible values. A greater proportion of consumers reported a descriptive THC:CBD ratio of their usual product, ranging from 50.9% of edible users to 78.2% of orally ingested oil users. Consumers were substantially more likely to report products high in THC versus low in THC for all products except topicals and tinctures, whereas similar proportions reported using products high and low in CBD. Despite some evidence of greater knowledge in legal jurisdictions, knowledge was still low in states with legal cannabis markets.

Conclusions:

Consumer knowledge of THC and CBD levels was low, with only modest differences between consumers living in jurisdictions that had and had not legalized nonmedical cannabis. The findings cast doubt on the validity of self-reported cannabinoid levels.

Keywords: Canada, cannabidiol, cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol, United States

Introduction

The cannabis market in North America is diversifying in terms of the number of products and modes of administration. Although smoking dried cannabis herb remains the most common mode of administration, use of other forms is increasing, particularly high-potency products, including vape oils and solid concentrates. There is also diversity within product categories, including their levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)1—the primary psychoactive cannabinoid in cannabis that produces impairment. Among commercially available dried herb products, THC levels can range from 1% or less to ∼30%.1–3 Vape oils can have an even greater range—from no THC to more than 90%—while cannabis edibles also vary from several milligrams to several hundred milligrams of THC in a single product.

At the same time, cannabidiol (CBD)-rich products are undergoing significant growth within the North American market.4 CBD is a psychoactive cannabinoid that (unlike THC) does not produce impairment when used alone. Compared with dried herb, CBD is traditionally present in higher concentrations in orally ingested oils and capsules. A broader use of CBD products as natural health products also has emerged in topical creams, often at subclinical concentrations. Anecdotal evidence further suggests that there is an increasing demand for dried herb that has higher levels of CBD or products with balanced levels of CBD and THC. This is likely due to preliminary research suggesting that CBD may have antipsychotic effects and/or moderate some of the impairment produced by THC.5,6

To date, most information on THC and CBD levels is from market scans or sales data in jurisdictions with legal cannabis markets. There is considerable interest in individual-level data to better understand implications of product potency on indicators of problematic use and potential adverse outcomes.7,8

Few studies have examined the accuracy of self-reported THC or CBD levels. One study asked consumers to descriptively categorize the potency (e.g., mild, average, and strong) of their cannabis products and found modest correlations with objectively determined THC concentrations, but to a lesser extent for dried herb compared with hash resin.9 Another study examined subjective estimates of cannabis potency using a scale from 1 (negligible effect) to 10 (incredibly strong).10 Estimated cannabis potency was modestly associated with actual THC concentration among daily users, but not nondaily users, with no differences across product types.

North American jurisdictions that have legalized medical and nonmedical cannabis have regulations that require THC (and in some cases CBD) levels to be labeled on cannabis products. Although the impact of these regulations has yet to be examined, several qualitative and experimental studies suggest that consumers have limited familiarity with THC numbers.11 Few consumers are aware of THC labeling, and consumers struggle to interpret THC numbers as indicators of potency for products such as cannabis edibles.12,13 Consumer difficulties understanding THC may be exacerbated by inconsistent labeling of cannabis products on the illicit market.14

The aim of the current article is to examine self-reported cannabinoid levels among cannabis consumers, with three specific objectives: (1) to examine the proportion of consumers who can report THC and CBD ratios and numeric THC and CBD levels; (2) to compare self-reported THC and CBD levels across each of nine cannabis product categories; and (3) to examine differences in self-reported knowledge of THC and CBD levels across three jurisdictions: US states that had legalized nonmedical cannabis as of August 2018, US states in which recreational cannabis remained illegal (US legal and illegal states, respectively), and in Canada in the year before recreational cannabis legalization.

Materials and Methods

Sample

Data are cross-sectional findings from Wave 1 of the International Cannabis Policy Study (ICPS).15 Data were collected using self-completed web-based surveys conducted from August 27 to October 7, 2018, with respondents aged 16–65 years. Respondents were recruited through the Nielsen Consumer Insights Global Panel and their partners' panels using nonprobability methods. E-mail invitations (with a unique link) were sent to a random sample of panelists (after targeting for age and country criteria); panelists known to be ineligible based on age and country were not invited. Surveys were conducted in English in the United States and English or French in Canada. Median survey time was 19.9 min.

Respondents provided consent before completing the survey. Respondents received remuneration in accordance with their panel's usual incentive structure (e.g., point-based or monetary rewards and chances to win prizes). The study was reviewed by and received ethics clearance through a University of Waterloo Research Ethics Committee (ORE #31330). A full description of the study methods, including participation rates, can be found in the International Cannabis Policy Study Technical Report.16

Measures

For full item wording, refer to the ICPS 2018 (Wave 1) survey.15 Participants reported past 12-month use of nine cannabis product types: dried herb (smoked or vaped), cannabis liquid/oil taken orally, cannabis liquid/oil for vaping, edibles (foods), drinks (e.g., cannabis cola, tea, and coffee), concentrates (e.g., wax and shatter), hash or kief, tinctures, and topical ointments.

For each product type, consumers were asked to report the THC-to-CBD ratio: “Which of the following best describes the type of [product] you usually use?” (High THC, Low CBD; High THC, High CBD; Low THC, Low CBD; Low THC, High CBD; Other; I don't know; or Refuse to answer). Past 12-month users of each product type were also asked to report numeric THC and CBD levels (“What are the THC and CBD levels in the [product] you usually use?”). Respondents could enter THC and CBD amounts in mg or % or select “Don't know” or “Refuse to answer”. Sociodemographic characteristics included sex at birth, age, race/ethnicity, highest level of education, and frequency of cannabis use (see response options in Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n=6471)

| Canada (n=2354) | US illegal states (n=1957) |

US legal states (n=2160) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | |||

| Age, years | |||

| (M, SD) | 37.8 (13.9) | 37.3 (14.2) | 38.3 (14.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 45.2% (1064) | 43.3% (848) | 47.0% (1015) |

| Male | 54.8% (1291) | 56.7% (1109) | 53.0% (1145) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 17.7% (417) | 15.0% (293) | 11.0% (237) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 27.5% (648) | 19.0% (372) | 19.2% (414) |

| Some college* | 35.9% (846) | 43.1% (844) | 45.0% (972) |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 18.9% (444) | 22.9% (448) | 24.8% (537) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 80.8% (1901) | 75.4% (1475) | 80.0% (1727) |

| Other/Mixed/Unstated | 19.2% (453) | 24.6% (482) | 20.0% (433) |

| Cannabis use frequency | |||

| < Once per month | 30.4% (716) | 29.1% (569) | 26.6% (575) |

| 1+ times/month | 18.0% (425) | 21.6% (423) | 19.1% (413) |

| 1+ times/week | 18.7% (440) | 17.5% (343) | 20.8% (450) |

| Daily/almost daily | 32.9% (774) | 31.8% (622) | 33.5% (723) |

Includes some college technical/vocational training, college certificate/diploma, apprenticeship, or some university.

Statistical analyses

A total of 28,471 respondents completed the survey. After removing 1302 respondents with invalid responses to data quality questions, ineligible country of residence, smartphone use (due to screen size concerns), or residence in District of Columbia (due to inadequate sample size), 27,169 respondents were retained. The current analysis was conducted among a subsample of 6471 respondents who reported using any form of cannabis in the past 12 months.

Poststratification sample weights were constructed based on the Canadian and US census estimates. Respondents from Canada were classified into age-by-sex-by-province and education groups. Respondents from the US legal states were classified into age-by-sex-by-legal state, education, and region-by-race groups, while those from the illegal states were classified into age-by-sex, education, and region-by-race groups. Correspondingly grouped population count and proportion estimates were obtained from Statistics Canada and the US Census Bureau.17,18 A raking algorithm was applied to the full analytic sample (n=27,169) to compute weights that were calibrated to these groupings.19,20 Weights were rescaled to the sample size for Canada, US illegal states, and US legal states. Estimates are weighted unless otherwise specified.

Logistic regression models were fitted to examine differences between jurisdictions in the proportion reporting a THC:CBD ratio (0=Don't know vs. 1=any THC:CBD ratio reported) and THC and CBD levels of nine products (0=Don't know vs. 1=any value reported). All models were adjusted for age, sex, education level, race/ethnicity, and cannabis use frequency. Analyses were conducted using survey procedures in SAS Studio 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1.

THC/CBD ratios

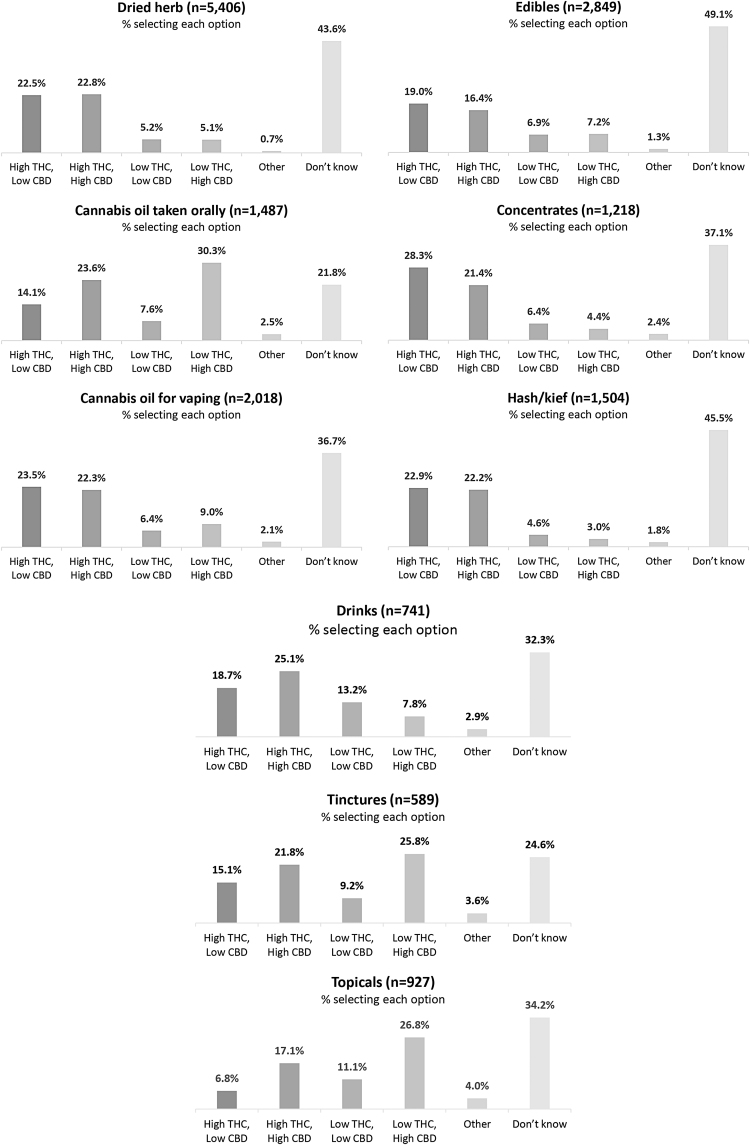

Figure 1shows the self-reported THC:CBD ratios for nine types of cannabis across jurisdictions. Across all products, participants were more likely to report products as being high in THC compared with low in THC. The proportion of CBD-rich products (those low in THC and high in CBD) was less than 10% for all products, with the exception of orally ingested oils, tinctures and topicals, for which a plurality chose either of the low THC ratios.

FIG. 1.

THC:CBD ratio of nine cannabis products reported by past 12-month users (all jurisdictions). THC, tetrahydrocannabinol; CBD, cannabidiol.

As shown in Table 2, consumers in US legal states were more likely to report knowing the THC:CBD ratio than consumers in Canada for eight of nine product categories, and more likely than consumers in US illegal states to report THC:CBD ratios for five of nine product categories.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Past 12-Month Users Who Reported the Tetrahydrocannabinol:Cannabidiol Ratio of the Product They Usually Use

| Product | Canada |

US illegal states |

US legal states |

Illegal states vs. Canada (ref) |

Legal states vs. Canada (ref) |

Legal vs. illegal states (ref) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | AOR (95% CI), p-value | |||||

| Dried herb (n=5406) | 50.2% (1001) | 52.1% (862) | 67.5% (1186) | 1.08 (0.90–1.30), 0.415 | 2.00 (1.61–2.47), <0.001 | 1.85 (1.50–2.29), <0.001 |

| Oil - oral (n=1487) | 73.1% (395) | 78.5% (326) | 83.1% (440) | 1.28 (0.85–1.93), 0.245 | 1.73 (1.21–2.67), 0.013 | 1.35 (0.85–2.16), 0.203 |

| Oil - vaped (n=2018) | 54.9% (279) | 59.4% (364) | 70.7% (634) | 1.16 (0.83–1.60), 0.386 | 2.04 (1.44–2.90), <0.001 | 1.77 (1.28– 2.44), <0.001 |

| Edibles/foods (n=2849) | 43.8% (407) | 45.8% (347) | 59.8% (695) | 1.04 (0.80–1.34), 0.785 | 1.93 (1.48–2.51), <0.001 | 1.86 (1.42–2.43), <0.001 |

| Concentrates (n=1218) | 56.3% (233) | 58.3% (179) | 71.2% (354) | 0.98 (0.64–1.50), 0.920 | 1.92 (1.25–2.96), 0.003 | 1.97 (1.25–3.09), 0.004 |

| Hash/kief (n=1504) | 45.4% (280) | 53.7% (186) | 65.4% (353) | 1.13 (0.85–1.78), 0.276 | 2.13 (1.46–3.12), <0.001 | 1.73 (1.14–2.63), 0.010 |

| Drinks (n=741) | 54.3% (106) | 75.0% (131) | 71.3% (265) | 2.33 (1.22–4.44), 0.010* | 1.99 (1.13–3.49), 0.017* | 0.85 (0.46–1.58), 0.614* |

| Tinctures (n=589) | 70.3% (115) | 80.8% (108) | 75.8% (222) | 1.75 (0.87–3.51), 0.115* | 1.46 (0.78–2.74), 0.240* | 0.83 (0.43–1.63), 0.594* |

| Topicals (n=927) | 52.8% (121) | 73.0% (165) | 68.7% (324) | 2.38 (1.44–3.93), <0.001 | 1.97 (1.25–3.10), 0.003 | 0.83 (0.51–1.33), 0.434 |

Significant differences between jurisdictions (p < 0.05) are indicated in bold.

Binary logistic regression (1=selected a ratio or “Other”; 0=“Don't know”), excluding “Refuse to answer”.

Regression models for drinks and tinctures produced quasi-separation of data points due to small cell sizes; results of these models should be interpreted with caution.

CI, confidence interval; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; ref, reference group.

Supplementary Tables S1–S9 show the contrasts for additional covariates included in the regression models. The odds of reporting the THC:CBD ratio for dried herb, cannabis oil ingested orally, vaped cannabis oil, edibles, and topicals were significantly greater among those who used cannabis more frequently. Males were also more likely to report the THC:CBD ratio of several products (dried herb, edibles, concentrates, cannabis oil for vaping, and hash/kief), as were those with higher levels of education (dried herb, edibles, and cannabis oil for vaping).

Self-reported numeric THC and CBD levels

As shown in Table 3, less than one third of consumers in each jurisdiction were able to report the numeric THC or CBD level for the cannabis products they usually used. Consumers in US legal states were more likely to report the usual THC levels of six of the nine product types compared with consumers in Canada (dried herb, vape oil, edibles, concentrates, hash, and drinks) as well as four products compared with consumers in US illegal states (dried herb, vape oil, edibles, and hash).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Past 12-Month Users Who Reported the Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol Levels of the Product They Usually Use

| Product | Canada |

US illegal states |

US legal states |

Illegal states vs. Canada (ref) |

Legal states vs. Canada (ref) |

Legal vs. illegal states (ref) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | AOR (95% CI), p-value | |||||

| THC | ||||||

| Dried herb (n=5017) | 11.4% (214) | 7.0% (107) | 18.3% (295) | 0.57 (0.41–0.79), <0.001 | 1.58 (1.19–2.09), <0.001 | 2.77 (2.01–3.81), <0.001 |

| Oil - oral (n=1330) | 28.0% (140) | 19.2% (73) | 26.1% (117) | 0.59 (0.38–0.92), 0.019 | 0.89 (0.58–1.36), 0.586 | 1.50 (0.93–2.42), 0.093 |

| Oil - vaped (n=1846) | 13.1% (63) | 14.1% (78) | 22.0% (179) | 1.02 (0.61–1.71), 0.944 | 1.85 (1.16–2.95), 0.010 | 1.82 (1.17–2.82), 0.008 |

| Edibles/foods (n=2665) | 14.5% (127) | 12.7% (89) | 23.6% (256) | 0.82 (0.56–1.20), 0.307 | 1.73 (0.98–1.00), 0.002 | 2.11 (1.48–3.01), <0.001 |

| Concentrates (n=1110) | 14.1% (54) | 19.2% (54) | 22.5% (101) | 1.22 (0.67–2.23), 0.523 | 1.84 (1.03–3.27), 0.039 | 1.51 (0.87–2.62), 0.154 |

| Hash/kief (n=1365) | 8.2% (47) | 10.7% (35) | 17.3% (81) | 1.26 (0.64–2.47), 0.506 | 2.56 (1.38–4.76), 0.003 | 2.04 (1.08–3.85), 0.029 |

| Drinks (n=624) | 14.9% (25) | 22.2% (33) | 28.4% (87) | 1.20 (0.55–2.62), 0.651 | 2.09 (1.06–4.13), 0.034 | 1.74 (0.88–3.44), 0.109 |

| Tinctures (n=505) | 22.9% (32) | 22.6% (26) | 31.9% (80) | 0.88 (0.37–2.07), 0.765 | 1.49 (0.69–3.19), 0.310 | 1.69 (0.85–3.37), 0.135 |

| Topicals (n=798) | 18.7% (39) | 19.5% (36) | 22.8% (92) | 1.04 (0.54–2.04), 0.899 | 1.32 (0.70–2.49), 0.389 | 1.27 (0.69–2.32), 0.447 |

| CBD | ||||||

| Dried herb (n=5017) | 9.7% (182) | 6.3% (95) | 14.3% (231) | 0.59 (0.42–0.84), 0.003 | 1.39 (1.02–1.88), 0.035 | 2.34 (1.66–3.30), <0.001 |

| Oil - oral (n=1330) | 27.2% (137) | 19.8% (75) | 25.6% (115) | 0.65 (0.42–1.01), 0.052 | 0.91 (0.59–1.38), 0.649 | 1.39 (0.87–2.24), 0.168 |

| Oil - vaped (n=1846) | 11.1% (53.1) | 13.1% (73) | 17.7% (144) | 1.11 (0.65–1.92), 0.702 | 1.67 (1.03–2.72), 0.038 | 1.51 (0.95–2.40), 0.085 |

| Edibles/foods (n=2665) | 10.0% (88) | 9.8% (69) | 17.0% (185) | 0.94 (0.60–1.46), 0.773 | 1.73 (1.16–2.58), 0.007 | 1.85 (1.23–2.79), 0.003 |

| Concentrates (n=1110) | 12.5% (48) | 19.4% (55) | 17.8% (79) | 1.41 (0.76–2.63), 0.277 | 1.53 (0.83–2.84), 0.177 | 1.08 (0.61–1.91), 0.781 |

| Hash/kief (n=1365) | 8.0% (45) | 10.5% (34) | 15.5% (73) | 1.24 (0.62–2.46), 0.542 | 2.27 (1.20–4.28), 0.012 | 1.83 (0.94–3.54), 0.073 |

| Drinks (n=624) | 11.2% (19) | 22.1% (33) | 23.2% (71) | 1.60 (0.70–3.68), 0.264 | 2.15 (1.02–4.53), 0.044 | 1.34 (0.67–2.68), 0.406 |

| Tinctures (n=505) | 19.5% (27) | 22.2% (25) | 33.2% (83) | 1.04 (0.42–2.56), 0.932 | 1.88 (0.85–4.18), 0.122 | 1.81 (0.90–3.63), 0.096 |

| Topicals (n=798) | 16.5% (35) | 19.4% (36) | 23.2% (94) | 1.20 (0.60–2.37), 0.609 | 1.57 (0.82–3.00), 0.177 | 1.31 (0.72–2.40), 0.383 |

Significant differences between jurisdictions (p < 0.05) are indicated in bold.

THC, tetrahydrocannabinol; CBD, cannabidiol.

A similar pattern was observed for CBD levels: consumers in US legal states were significantly more likely to report the CBD levels for five product types compared with those in Canada (dried herb, vape oil, edibles, hash, and drinks) and for two product types compared with those in US illegal states (dried herb and edibles). As shown in Supplementary Tables S1–S9, with the exception of concentrates, hash/kief, and drinks, the odds of reporting THC and/or CBD levels differed by frequency of use, such that those who used cannabis more frequently were more likely to report THC or CBD levels.

Tables 4 and 5 show the mean THC and CBD levels reported for usual products in the unit selected by consumers. With the exception of dried herb and cannabis oil for vaping, both units—mg and % THC—were reported by at least one third of consumers. As shown in Tables 4 and 5, a wide range of THC and CBD levels were reported for each product type. For example, 7.2% of dried herb consumers reported THC levels <15%, 63.3% reported THC levels between 15% and 30%, and 29.5% reported THC levels >30%. Fewer daily users of dried herb (20.4%) reported THC levels >30% compared with those who used it weekly (36.9%), monthly (39.6%), or less than once a month (31.2%).

Table 4.

Usual Tetrahydrocannabinol Levels (mg or %) Reported by Past 12-Month Users of Each Product Type, by Jurisdiction

| Product and unit (% or mg) | Canada |

US illegal states |

US legal states |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median, mode, and range | Mean (SD) | Median, mode, and range | Mean (SD) | Median, mode, and range | |

| Dried herb | ||||||

| % (n=477) | 32.9 (22.4) | 24.0, 20.0, 1–100 | 42.0 (28.2) | 29.4, 80.0, 0–100 | 30.7 (19.5) | 24.0, 20.0, 0–96 |

| mg (n=142) | 46.0 (209.1) | 10.0, 2.0, 2–1500 | 20.3 (23.7) | 10.0, 10.0, 1–100 | 41.2 (52.1) | 22.9, 20.0, 1–300 |

| Oil - oral* | ||||||

| % (n=196) | 24.5 (23.7) | 22.8, 25.0, 0–90 | 27.2 (31.6) | 19.0, 0.0, 0–100 | 18.6 (22.4) | 10.0, 0.0, 0–95 |

| mg (n=143) | 76.0 (256.7) | 3.0, 1.0, 0–1500 | 6.2 (8.0) | 3.0, 1.0, 0–25 | 20.9 (29.3) | 10.0, 0.0, 0–162 |

| Oil - vaped | ||||||

| % (n=230) | 49.6 (34.3) | 47.7, 25.0, 0–100 | 41.1 (34.5) | 25.0, 0.0, 0–100 | 49.9 (31.8) | 50.0, 22.0, 0–95 |

| mg (n=93) | 58.2 (122.6) | 12.0, 12.0, 0–750 | 11.5 (18.8) | 4.0, 1.0, 0–92 | 127.9 (272.9) | 10.0, 1.0, 0–1000 |

| Edibles/foods | ||||||

| % (n=161) | 40.4 (29.2) | 34.1, 60.0, 0–100 | 35.2 (27.2) | 27.7, 80.0, 0–90 | 38.6 (25.9) | 35.0, 50.0, 0–100 |

| mg (n=312) | 71.7 (122.3) | 25.0, 100.0, 0–800 | 50.1 (156.0) | 10.0, 1.0, 0–1000 | 60.8 (95.7) | 10.0, 10.0, 0–500 |

| Concentrates | ||||||

| % (n=134) | 57.0 (27.6) | 54.2, 90.0, 5–100 | 46.1 (31.2) | 36.0, 50.0, 1–100 | 64.8 (28.7) | 72.7, 95.0, 5–100 |

| mg (74) | 10.0 (20.2) | 3.0, 3.0, 2–150 | 17.8 (24.2) | 10.0, 10.0, 1–100 | 38.9 (49.0) | 15.4, 10.0, 1–144 |

| Hash/kief | ||||||

| % (n=90) | 32.7 (24.6) | 25.0, 25.0, 1–100 | 54.6 (28.3) | 61.4, 80.0, 10–90 | 54.9 (29.3) | 50.0, 50.0, 2–100 |

| mg (n=72) | 70.8 (184.3) | 6.0, 2.0, 2–750 | 15.1 (24.5) | 6.1, 5.0, 1–100 | 24.8 (34.3) | 10.0, 10.0, 0–200 |

| Drinks | ||||||

| % (56) | 38.7 (33.7) | 37.2, 56.0, 1–100 | 36.7 (30.2) | 30.9, 50.0, 0–90 | 38.8 (30.0) | 30.0, 10.0, 1–100 |

| mg (n=89) | 28.2 (43.5) | 10.0, 10.0, 2–220 | 20.2 (28.0) | 10.0, 20.0, 1–100 | 43.5 (52.9) | 15.0, 10.0, 0–180 |

| Tinctures | ||||||

| % (n=68) | 28.0 (34.2) | 10.0. 75.0, 0–100 | 26.2 (21.0) | 34.0, 50.0, 0–56 | 18.1 (21.4) | 10.4, 0.0, 0–70 |

| mg (n=71) | 297.9 (383.4) | 100.2, 900, 0–900 | 81.0 (256.6) | 5.2, 4.0, 0–1000 | 32.2 (44.3) | 10.0, 0.0, 0–175 |

| Topicals | ||||||

| % (n=93) | 13.0 (26.7) | 5.0, 0.0, 0–100 | 19.5 (19.6) | 10.0, 50.0, 0–50 | 22.7 (27.6) | 10.0, 0.0, 0–90 |

| mg (n=77) | 79.3 (120.5) | 10.0, 10.0, 0–400 | 16.1 (18.2) | 10.0, 10.0, 0–74 | 24.1 (57.5) | 5.0, 10.0, 0–530 |

THC and CBD levels of orally administered cannabis oil are typically labelled in mg/mL; however, the survey permitted respondents to report in % or mg.

Table 5.

Usual Cannabidiol Levels (mg or %) Reported by Past 12-Month Users of Each Product Type, by Jurisdiction

| Product and unit (% or mg) | Canada |

US illegal states |

US legal states |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median, mode, and range | Mean (SD) | Median, mode, and range | Mean (SD) | Median, mode, and range | |

| Dried herb | ||||||

| % (n=395) | 23.6 (22.5) | 18.0, 1.0, 0–100 | 34.9 (30.3) | 27.3, 50.0, 0–100 | 19.6 (25.4) | 7.0, 0.0, 0–96 |

| mg (n=122) | 27.0 (119.2) | 4.0, 2.0, 0–750 | 54.7 (166.0) | 7.0, 1.0, 1–1000 | 38.8 (66.5) | 15.0, 2, 0–250 |

| Oil - oral* | ||||||

| % (n=189) | 34.0 (33.1) | 21.4, 10.0, 0–100 | 56.9 (32.9) | 50.0, 100.0, 0–100 | 47.7 (38.5) | 4.6, 100, 0–100 |

| mg (n=142) | 63.7 (197.4) | 20.0, 20.0, 0–1200 | 144.6 (313.5) | 5.0, 5.0, 0–1250 | 203.0 (375.1) | 25.0, 1000, 0–1000 |

| Oil - vaped | ||||||

| % (n=191) | 28.8 (22.9) | 25.0, 25.0, 0–100 | 30.9 (30.1) | 19.0, 7.0, 0–100 | 27.8 (32.6) | 15.0, 1.0, 0–100 |

| mg (n=79) | 39.7 (75.2) | 5.0, 5.0, 0–250 | 49.3 (180.9) | 3.0, 3.0, 1–1000 | 24.2 (81.3) | 10.0, 15.0, 0–1000 |

| Edibles/foods | ||||||

| % (n=153) | 37.2 (24.8) | 40.0, 40.0, 0–100 | 31.8 (29.2) | 4.8, 80.0, 0–90 | 26.9 (23.6) | 25.0, 50.0, 0–100 |

| mg (n=189) | 25.0 (48.6) | 4.0, 0.0, 0–250 | 17.3 (25.8) | 10.0, 10.0, 0–100 | 36.0 (91.3) | 10.0, 10.0, 0–500 |

| Concentrates | ||||||

| % (n=105) | 30.3 (23.8) | 30.0, 10.0, 0–80 | 42.7 (34.6) | 45.0, 50.0, 2–100 | 18.2 (19.8) | 12.1, 0.0, 0–80 |

| mg (n=78) | 4.3 (2.7) | 3.0, 3.0, 2–10 | 68.7 (223.1) | 5.0, 10.0, 1–1000 | 32.2 (43.8) | 15.0, 15.0, 0–124 |

| Hash/kief | ||||||

| % (n=85) | 18.9 (15.2) | 3.1, 25.0, 0–60 | 45.6 (30.2) | 45.0, 80.0, 4–90 | 21.9 (19.5) | 14.2, 50.0, 0–67 |

| mg (n=67) | 34.8 (79.5) | 10.0, 1.0**, 1–250 | 10.1 (14.8) | 5.0, 5.0, 1–97 | 15.1 (20.6) | 10.0, 25.0, 1–100 |

| Drinks | ||||||

| % (n=55) | 28.8 (24.3) | 21.4, 55.0, 0–80 | 45.9 (32.3) | 40.5, 50.0, 5–100 | 25.7 (22.7) | 15.0, 10.0, 0–99 |

| mg (n=68) | 6.6 (14.3) | 2.0, 2.0, 0–100 | 12.3 (22.8) | 4.8, 4.0, 1–150 | 15.0 (19.2) | 15.0, 15.0, 0–100 |

| Tinctures | ||||||

| % (n=69) | 48.0 (29.5) | 40.0, 25.0, 0–100 | 53.7 (31.0) | 47.6, 45.0, 2–99 | 47.2 (35.2) | 45.0, 100.0, 3–100 |

| mg (n=67) | 41.1 (42.7) | 27.9, 100.0, 0–150 | 34.5 (111.6) | 4.6, 3.0, 1–750 | 169.1 (261.5) | 60.0, 5.0, 0–1000 |

| Topicals | ||||||

| % (n=92) | 53.0 (40.7) | 40.0, 100.0, 0–100 | 45.5 (34.0) | 34.3, 30.0, 1–100 | 40.2 (36.8) | 25.0, 1.0, 1–100 |

| mg (n=72) | 45.7 (80.1) | 5.0, 5.0, 2–300 | 38.2 (142.6) | 10.0, 10.0, 2–1000 | 93.3 (164.1) | 10.0, 2.0, 1–500 |

THC and CBD levels of orally administered cannabis oil are typically labeled in mg/mL; however, the survey permitted respondents to report in % or mg.

Multiple modes exist; the smallest value is shown.

Discussion

The current study casts doubt on the validity of self-reported cannabinoid levels in cannabis products. Between one fifth and one half of consumers were unable to report even a descriptive ratio of THC and CBD for their usual cannabis product. The current findings are consistent with a 2019 national survey conducted in Canada, in which almost one third of past 12-month users reported not knowing the general THC-to-CBD ratios of the products they typically use.21 THC labeling of cannabis products outside of the legal market is inconsistent and of dubious value.14 Instead, many consumers infer potency from references to the cannabis strain—either broad categories, such as Sativa, Indica, or Hybrid, or specific strains such as Purple Kush—none of which are reliable indicators of THC or CBD levels.22,23

With the exception of dried herb and cannabis oil for vaping, numeric THC levels in mg and percent THC were each reported by at least a third of consumers; this diversity reflects the range of labeling units used for some products, such as oils, as well as a lack of familiarity with these numbers.

In the current study, there was no way to objectively verify the accuracy of the self-reported THC and CBD levels provided by consumers. However, even among consumers who reported knowing THC and CBD levels, many reported implausible values. Indeed, among dried herb consumers who reported THC levels using a percentage, about 30% reported a value higher than 30% THC, a level that (to our knowledge) is not commonly available.3 A recent scan conducted by our group found that <1% of dried herb products on the legal and illegal markets in Canada exceeded 30% (unpublished data). Similar proportions reported implausible data for CBD levels in dried herb: a 2018 scan of the Canadian market found that dried herb contained an average of 2% CBD,3 whereas respondents in the current study reported a mean of at least 20% CBD in all three jurisdictions.

This poor awareness of cannabinoid levels is consistent with a previous study in which the majority of respondents believed that low- and high-THC strains of cannabis contained ≥20% and ≥40% THC—concentrations reflective of high-THC strains and exceeding those in existing strains, respectively. Likewise, average concentrations provided for low- and high-CBD strains were ≥30% and ≥40% CBD, respectively.24 Low levels of consumer knowledge are also reflected in the units selected by consumers when reporting THC levels. Approximately one quarter of dried herb consumers reported THC levels in mg, while one third of edible consumers reported THC levels in percentages—units that are rarely used for these product types in labeling or anecdotally.

These findings are broadly consistent with other studies that objectively tested THC levels in cannabis products and observed only modest correlations with self-reported THC levels using ordinal potency scales.8,9 In addition, the current study found that consumers who use cannabis products more frequently were more likely to report THC:CBD ratios and to report THC levels within a valid range, similar to previous studies.9

Several differences in self-reported THC and CBD levels were observed across product categories. Consumers were more likely to report knowing THC:CBD ratios for oils and tinctures, which are more often used for medical purposes and therefore may be more likely to be packaged and labeled. In terms of numeric values, consumers reported lower THC percentages for dried herb compared with vape oil or solid concentrates, which would be expected; however, not to the same magnitude as suggested by sales data from legal jurisdictions.1

Self-reported THC and CBD levels also differed to some extent between jurisdictions that had and had not legalized nonmedical cannabis. Compared with consumers in Canada (before federal legalization in October 2018) and US illegal states, consumers in US legal states were more likely to report knowing THC and CBD numbers and to report numbers within plausible ranges. Greater knowledge in legal jurisdictions was restricted to products such as dried herb and hash/kief, which are less likely to be sold in packages displaying THC and CBD numbers on the illicit market.

Despite some evidence of greater knowledge in legal jurisdictions, knowledge was still low in states with legal cannabis markets: for example, less than 20% of dried herb consumers in legal states were able to report usual THC levels and only two-thirds were able to report THC:CBD ratios. In addition, few differences were observed between legal and illegal jurisdictions for products that are almost always sold in manufactured packaging and may be more likely to be used by medical users (e.g., orally ingested oils, topicals, and tinctures). Overall, the findings suggest that labeling practices in US states that have legalized nonmedical cannabis may have a modest, but limited, impact on consumer knowledge of THC and CBD levels. These findings are similar to experimental studies that demonstrate low levels of comprehension for THC numbers and serving sizes of cannabis edibles.10,11,13,25

Future research should examine the efficacy of alternative labeling practices for communicating THC and CBD levels. For example, shortly after the current study was conducted, Canada implemented labeling regulations that require concentrations of dried herb to be labeled using two different numbers for THC, which correspond to the percentage of THC (quantity of active cannabinoids present before combustion, that is, before decarboxylation) and total THC (quantity of active cannabinoids after combustion, including THC and tetrahydrocannabinolic acid [THCA]). The extent to which these labeling practices enhance or reduce consumer understanding of THC and CBD levels should be examined. The results also suggest that efforts should be undertaken to educate consumers, such as concise guidelines to help contextualize potency levels at the point of purchase at legal physical and online retailers.

Study limitations

This study is subject to limitations common to survey research. Respondents were recruited using nonprobability-based sampling; therefore, the findings do not provide nationally representative estimates. The data were weighted by age group, sex, and region in both countries and region-by-race in the US. However, the study sample was somewhat more highly educated than the national population in the US. In both countries, the ICPS sample had poorer self-reported general health compared with the national population, which is a feature of many nonprobability samples,26 and may be partly due to the use of web surveys, which provide greater anonymity than in-person or telephone-assisted interviews often used in national surveys.27

The rates of cannabis use were also somewhat higher than national samples; however, this is likely due to the fact that the ICPS sampled individuals aged 16–65 years, whereas the national surveys included older adults who may have lower rates of cannabis use. The ICPS is also conducted online, whereas most national surveys are conducted in person. Compared with interviewer-assisted survey modes, self-administered surveys can reduce social desirability bias by providing greater anonymity for sensitive topics, including substance use.28,29

Analyses compared Canada and US states with and without legal nonmedical cannabis laws. Future research should examine whether differences in THC knowledge exist between states with legal nonmedical versus medical cannabis laws. In addition, the survey measures asked consumers to report the ratios and levels of THC and CBD for the products of each category they usually use; it is possible that some respondents selected “Don't know” because they use a wide range of products with varying cannabinoid levels equally, rather than because of a lack of knowledge. Finally, self-reported THC and CBD levels could not be verified.

Conclusions

The findings indicate low consumer knowledge of the primary cannabinoids in cannabis products, including THC, the primary impairment-inducing psychoactive constituent. There is a need for greater consumer education regarding cannabinoid levels, particularly given the increasing diversity of cannabis products and consumer difficulties in effectively titrating the THC dosage.11,12 Although there is some indication of more accurate reporting of THC and CBD levels among consumers residing in jurisdictions that have legalized nonmedical cannabis and mandated THC labeling on cannabis products, the findings also highlight the need for enhanced labeling in legal jurisdictions.

Finally, despite the potential utility of collected self-reported data on THC and CBD levels in population-based surveys, the accuracy of these data is dubious and should be interpreted with considerable caution. Given the questionable validity of the THC and CBD values provided by consumers herein, the authors urge readers to focus on the broader pattern of findings, including greater knowledge of THC-to-CBD ratios among specific product types (e.g., orally ingested oils and tinctures) and consumer groups (e.g., more frequent and/or educated consumers). Future research should evaluate novel labeling practices that may improve consumer knowledge of THC, including the Canadian regulation that edibles can contain a maximum of 10 mg of THC per package.30

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Vicki Rynard and Christian Boudreau for their assistance with creating survey weights for the larger International Cannabis Policy Study.

Abbreviations Used

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CBD

cannabidiol

- ICPS

International Cannabis Policy Study

- THC

tetrahydrocannabinol

- THCA

tetrahydrocannabinolic acid

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

Funding for this study was provided by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Project Bridge Grant (PJT-153342) and a CIHR Project Grant (DH). Additional support was provided by a Public Health Agency of Canada–CIHR Chair in Applied Public Health (DH). The funders had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; report writing; or decision to submit the report for publication.

Supplementary Material

Cite this article as: Hammond D, Goodman S (2022) Knowledge of tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol levels among cannabis consumers in the United States and Canada, Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 7:3, 345–354, DOI: 10.1089/can.2020.0092.

References

- 1. Caulkins JP, Bao Y, Davenport S, et al. Big data on a big new market: insights from Washington State's legal cannabis market. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;57:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, et al. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008–2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2019;269:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mahamad S, Wadsworth E, Rynard VL, et al. Availability, retail price, and potency of legal and illegal cannabis in Canada after recreational cannabis legalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubin R. Cannabidiol products are everywhere, but should people be using them? JAMA. 2019;322:2156–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iseger TA, Bossong MG. A systematic review of the antipsychotic properties of cannabidiol in humans. Schizophr Res. 2015;162:153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hindley G, Beck K, Borgan F, et al. Psychiatric symptoms caused by cannabis constituents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:344–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Russell C, Rueda S, Room R, et al. Routes of administration for cannabis use - basic prevalence and related health outcomes: a scoping review and synthesis. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;52:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Pol P, Liebregts N, de Graaf R, et al. Validation of self-reported cannabis dose and potency: an ecological study. Addiction. 2013;108:1801–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freeman TP, Morgan CJ, Hindocha C, et al. Just say ‘know’: how do cannabinoid concentrations influence users' estimates of cannabis potency and the amount they roll in joints? Addiction. 2014;109:1686–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hammond D. Communicating THC levels and ‘dose’ to consumers: implications for product labelling and packaging of cannabis products in regulated markets. Int J Drug Policy. 2019:102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kosa KM, Giombi KC, Rains CB, et al. Consumer use and understanding of labelling information on edible marijuana products sold for recreational use in the states of Colorado and Washington. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;43:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leos-Toro C, Fong GT, Meyer SB, et al. Cannabis labelling and consumer understanding of THC levels and serving sizes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vandrey R, Raber JC, Raber ME, et al. Cannabinoid dose and label accuracy in edible medical cannabis products. JAMA. 2015;313:2491–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hammond D, Goodman S, Leos-Toro C, et al. International Cannabis Policy Study Wave 1 Survey (2018). (Aug 2018). Available at: http://cannabisproject.ca/methods/ (accessed Feb 2020).

- 16. Goodman S, Hammond D. International Cannabis Policy Study: Technical Report – Wave 1 (2018). (April 2019). Available at: http://cannabisproject.ca/methods/ (accessed Feb 2020).

- 17. Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0005-01 Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex, 2017. (2019). Available at: www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501 (accessed Feb 2020).

- 18. US Census Bureau. 2013. –2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. (2017). Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_S1501&src=pt (accessed Feb 2020).

- 19. ABT Associates. Raking survey data (a.k.a. sample balancing). (2020). Available at: www.abtassociates.com/raking-survey-data-aka-sample-balancing (accessed Feb 2020).

- 20. Battaglia M, Izrael D, Ball S. Tips and tricks for raking survey data with advanced weight trimming. SESUG Paper SD-62-2017. (2017). Available at: www.abtassociates.com/sites/default/files/files/Insights/Tools/SD_62_2017.pdf

- 21. Government of Canada. Canadian Cannabis Survey 2019 - Summary. (2019). Available at: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-cannabis-survey-2019-summary.html (accessed Feb 2020).

- 22. Mudge EM, Murch SJ, Brown PN. Chemometric analysis of cannabinoids: chemotaxonomy and Domestication Syndrome. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jikomes N, Zoorob M. The cannabinoid content of legal cannabis in Washington State varies systematically across testing facilities and popular consumer products. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kruger DJ, Kruger JS, Collins L. Frequent cannabis users demonstrate low knowledge of cannabinoid content and dosages. Drugs (Abingdon Engl). 2020; DOI: 10.1080/09687637.2020.1752150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goodman S, Hammond D. Does unit-dose packaging influence understanding of serving size information for cannabis edibles? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2020;81:173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fahimi M, Barlas F, Thomas R. A Practical Guide for Surveys Based on Nonprobability Samples [Webinar]. American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR). (February 13, 2018). Available at: https://register.aapor.org/detail.aspx?id=WEB0218_REC

- 27. Hays RD, Liu H, Kapteyn A. Use of internet panels to conduct surveys. Behav Res. 2015;47:685–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dodou D, de Winter J. Social desirability is the same in offline, online, and paper surveys: a meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;36:487–495. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krumpal I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Qual Quant. 2013;47:2025–2047. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Government of Canada. Final regulations: edible cannabis, cannabis extracts, cannabis topicals. (Sept 2019). Available at: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/resources/regulations-edible-cannabis-extracts-topicals.htmlPublished2019 (accessed Feb 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.