Abstract

Background:

Despite cannabis's societal ubiquity, several African states remain traditional prohibitionists. However, cannabis is becoming a more explored frontier from a health, human rights, and monetary perspective. A number of African countries have taken to tailoring their policies to better engage in emerging global dialogs. Nevertheless, the focus is majorly on the crop's financial appeal with less consideration on impacts of policies. This review aimed to specifically focus on the identification of existing or pending policies, indicating national positioning in terms of recreational and medicinal cannabis use and summarizing publications addressing related impacts in Africa.

Methods:

We systematically searched six academic research databases (including Google Scholar), Google, country specific websites, and websites of relevant organizations. Included publications were in English and published between January 1, 2000, and November 31, 2020 (with exception granted to official legislation not in English and/or published earlier than 2000, but still in effect). Reference lists of included publications were screened for potentially relevant publications. Results were synthesized thematically and descriptively.

Results:

Cannabis is Africa's most consumed illegal substance, its use entrenched in social, political, historical, economic, and medicinal ties. African users constitute a third of the worldly total and cultivation is a major activity. Policies have led to prison overcrowding, accelerated environmental damage, and sourced regional instability. South Africa, Seychelles, and Ghana have decriminalized personal use with Egypt and Mozambique exploring similar legislation. Eleven countries have existing or pending medicinal cannabis-specific provisions. South Africa and Seychelles stand out as having regulations for patients to access medicinal cannabis. Other countries have made provisions geared toward creating export markets and economic diversification.

Conclusion:

Cannabis policy is a composite and complex issue. Official stances taken are based on long withstanding narratives and characterized by a range of contributing factors. Policy changes based on modern trends should include larger studies of previous policy impacts and future-oriented analysis of country-level goals incorporated with a greater understanding of public opinion.

Keywords: cannabis, policy, Africa, recreational cannabis, medicinal cannabis

Introduction

Cannabis is defined as “all parts of the plant Cannabis sativa L. (Cannabaceae); the seeds; extracted resin; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such plant, its seeds or resin.”1 By weight and value, it is the most widely consumed and traded illegal drug.2 Originating over 12,000 years ago from Asia, years of intracontinental trade and its many properties led to ubiquity.3

Indigenous use dates back to 14th century Ethiopia,4 with its arrival as a commodity.5 Use garnered popularity in, inter alia, cultural and medicinal practices, including by Congo's Aka forest-forager group as a helminthic (worm infection) protectant,6,7 by Sierra Leonean midwives as anesthesia,4 and by warriors and Southern African healers (Sangomas).2

During the introduction of colonialism (1870s–1890s), cannabis was legal. However, colonial governments reduced production8 to curb diversion from state generating activities (e.g., copal production) and promote the European mission of “civilizing” natives,6,9 leading to enactment of racialized policies to strengthen authoritarianism.5 In the early 20th century, medicinal use also began to fall out of favor as Western medicine began to focus on isolated chemical entities and international prohibitions soon followed.10

The Geneva Convention on Opium and Other Drugs (1925) first outlawed cannabis in many colonies.7 By the mid-20th century, liberation movements brought about new governments, but independent nations inherited colonial-era laws, due to international agreements and elitist control,8 and in some instances, more stringent measures have been enacted.11 Governments have shown varying levels of tolerance, notably, Morocco's lax position draws from past contexts.12

Cannabis is restricted to medical and scientific use under Schedule I and IV of the United Nations' Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961).13 However, affairs concerning cannabis are nationally regulated. Drug policies include supply reduction, access, cultivation, and treatment aspects. African nations are traditionally prohibitionists; however, the wave of global shifting sentiments has been influential. Emphasizing on policy redefinition, cannabis is becoming a more explored frontier from a health and human rights perspective and as a pharmaceutical entity.

There exists a gap in research on African cannabis policies, thereby making implementation of future evidence-based policy regulating use challenging. This study did not aim to provide insight of all aforementioned aspects, but specifically focus on the identification of existing or pending policies, indicating national positioning in terms of recreational and medicinal cannabis use and summarizing publications addressing related impacts in Africa.

Methods

This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. The protocol is uploaded on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42020211723).

Search strategy

Academic research database search

Publication retrieval included structured queries in five literature databases (African Journals Online, EBSCO, ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science) from 2000 up to and including November 2020. Google Scholar was additionally searched for the first 100 references as sorted by relevance. Free-text key terms and medical subject headings (MeSH terms) were incorporated and tailored to each database (Supplementary File S1). To ensure inclusivity of up-to-date results, searching was conducted first in July 2020 and rerun in November 2020.

Gray literature search

Google extraction

We used customized searches and relevancy ranking to identify publications. The first 10 pages of each search (representing 100 results) were reviewed, using title and short-text underneath (Supplementary File S2).

Targeted browsing of relevant organizations

Using a variety of keywords, we searched websites of country-specific organizations (government, health organizations, universities, etc.) for relevant works. Google search was first conducted to identify relevant organizations, including the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), The World Health Organization (List of Globally identified Websites of Medicines Regulatory Authorities14), and International Drug Policy Consortium.

This process was conducted through (1) Website-Searching: using search bars and keywords, (2) Website-Browsing: homepages were searched for information using selection menus, directories, and links, and (3) Country specific website-browsing: browsing of official websites of national authorities (Supplementary File S3).

Definition of legislation

For a more comprehensive review, a liberal definition of legislation was adopted, which we defined as any government documentation making reference to the status of cannabis for a defined region.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion extended to United Nations (UN) fully recognized sovereign African states, with nonsovereign states and disputed territories excluded. Publication inclusion applied to peer-reviewed materials (articles, chapters, etc.) and gray literature works (reports, policy literature, web articles, dissertations, etc.) exploring policies or impact. Results were restricted to English language works published between January 1, 2000, and November 31, 2020, with exceptions made for non-English legislation (whereby in such cases, the Google Translate feature was used to extract information) and/or in effect legislation published before 2000. A snowball strategy was also employed to further identify material.

Data extraction and synthesis

Search terms and number of results retrieved and screened from each search strategy were recorded. Publications meeting the preliminary inclusion criteria were indexed in a citation manager. Two authors independently reviewed titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles following duplicates removal. In the event of unavailable or inadequately detailed abstracts, publications were screened in their entirety. We used a fit-for-purpose quality criteria to select meaningful gray materials.15

Using Tyndall's “Checklist of Appraising Grey Literature” principles, each reviewer scrutinized gray literature in terms of Reputability: website domain and content creator information (individual or organization credentials); Accuracy: spelling or grammatical errors; Currency: date of creation or last updated; Objectivity: factual information presentation; Significance: existing relevance of information; and Credibility: references given to support information.16 Inclusion disputes concerning a source were moderated by a second evaluation by reviewers or, if necessary, through a third reviewer.

Data retrieval and analysis were undertaken concomitantly during data extraction and further refined during the inclusion process. Data were pooled by way of thematic narrative analysis into broad groupings. A meta-analysis was out of this study's capacity due to limited quantitative data and the diversity of publications.

Analytical framework

The main study question, that is, “What is the current status of formal cannabis policy and their impacts in Africa?” was approached through identification of cannabis policies and related impacts. A framework, adapted by van het Loo et al.,17 was expanded and adjusted to the study focus (Fig. 1). The original framework presented the primary goal of cannabis policy as “controlling consumption and channeling consequences”; to this, we included “providing regulated access to medicinal products.” This is because some policies do not solely aim to reduce use, but also create regulated markets for cultivation and sale. Our restructuring presents medicinal and recreational policies as subcategories to enable us to cover the entire debate.

FIG. 1.

Analytical framework.

We also focused on providing an overview of direct (seizures, arrests, health effects, etc.18) and indirect impacts. Given the intricacies of assessing health effects, we did not provide in-depth analysis of such content. Indirect consequences range from political to social. In this study, we focused on social aspects, with references made to the environment due to Africa's agrarian-based image.

Results

Description of search results

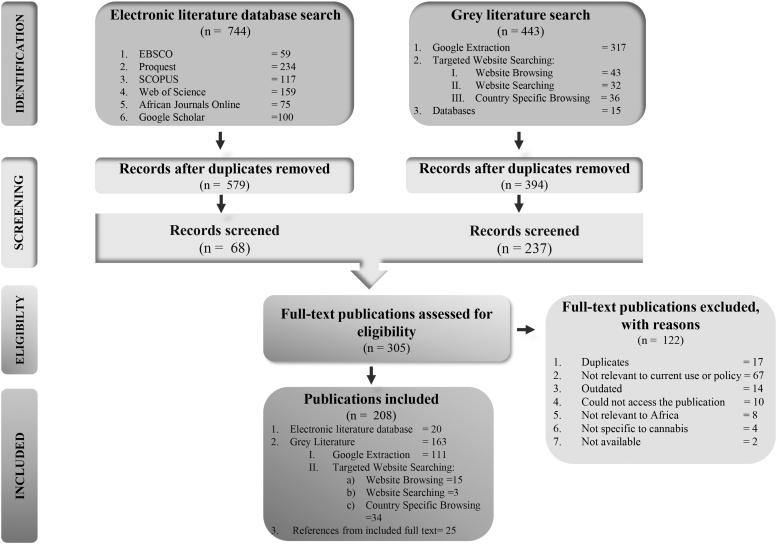

Fifty-four fully recognized states (according to UN membership) were eligible to have their cannabis policies researched, while two disputed territories, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic and Somaliland, were excluded due to no UN recognition. We retrieved 1183 records (740 from literature databases and 443 from gray literature searches). After removal of 231 duplicates, 952 records were initially screened. Texts of 305 records were fully screened.

Totally, 208 records (20 from academic research databases, 163 from gray literature searches, and 25 from snowballing) fulfilled the eligibility criteria for inclusion (Fig. 2). Scholarly databases identified 20 publications, suggesting reliance on a singular strategy would have led to a less comprehensive review. A total of 14 non-English documents (all government documents) were found to be relevant and translated.

FIG. 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

The majority of publications were web articles and legislation documents, both nearly constituting a third of all publications (n=63 [30%]). The most thorough strategy was Google extraction, identifying 116 (55%) publications. East Africa was represented by 62 publications (29.8%) from 18 countries, West Africa 54 (26.0%) from 16, Southern Africa 38 (18.3%) from 5, North Africa 28 (13.5%) from 6, Central Africa 12 (5.8%) from 9 and 14 (6.7%) composite publications (Supplementary File S4).

Mapping of existing and pending policies

All included countries are UN and African Group members. The drug control realm is governed by the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961), the Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971), and the Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (1988).19 Cannabis-related activities are prohibited in all Single Convention signatories states.20 Fifty-two African states are signatories to all conventions.13 As of 2019, 22 countries were reported to have National Drug Control Plans or Strategies21 to address local use, including Ethiopia,22 South Africa,5,23 Mauritius,24 The Gambia,24 and Nigeria.25

Cannabis policies were grouped as illegal (may refer to illegal; illegal, but decriminalized and unregulated; or illegal consumption, but legal cultivation), decriminalized (systems in which possession or use of any amount is noncriminal or depending on amount punishable by civil penalties), or legal (ranging from technically legal, but not legally available; legal, but no formal access; or fully regulated with formal access)17,26 (Table 1). In all cases, reference is to personal consumption, unless otherwise stated. All data are current to end of November 2020.

Table 1.

Mapping of Existing and Pending Recreational and Medicinal Cannabis Policies

| Country | Legislation | Recreational | Medicinal | Regulatory authority | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | Law No. 04-18 of December 25, 2004, on prevention and repression of illicit use and trafficking of narcotics and psychotropic substances97 | Illegal98 (Article 12) | Illegal | National Anti-Drugs and Drug Addiction Office, Algerian Ministry of Justice | The basis of the legal response to drug use is preventive and treatment measures.84 Sanctions only enforced upon the refusal of treatment (Article 9)99 |

| Angola | Law on trafficking and consumption of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances, and precursors—Law No. 3/99, of 6 August100 | Illegal101 (Article 18) | Illegal | National Directorate for Medicines | |

| Benin | Act No. 97-025 on the control of drugs and precursors, 1997102 | Illegal (Article 8) | Illegal | Central Office for Repression of Illicit Trafficking of Drugs and Precursors18 | No formal alternatives to incarceration, exemptions maybe granted for minors or first time offenders103 |

| Botswana | Illicit traffic in narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances bill, 2018.104 Medicines and Related Substances Act, 2013105 |

Illegal (Sections 4–6 of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances bill) | Illegal | Medicines Regulatory Authority105 | |

| Burkina Faso | Law No. 017/99/AN, 1999106 | Illegal | Illegal | National Committee to Combat Drug Abuse (CNLD) | Inter-ministerial committees are designated to oversee and support implementation103 |

| Burundi | No framework found | Illegal28,26 | Illegal26 |

|

|

| Cabo Verde | Law No. 78/IV/93 (1993) and Law No. 92/92 (1992)103,107 | Illegal (Article 1 of Law No. 92/92) | Illegal | Coordinating Commission to Combat Drugs18 | Defendants may seek treatment and a financial penalty in exchange for incarceration103 |

| Cameroona | Law No. 97-August 19, 1997, relative to the control of drugs, psychotropic substances, and precursors and on mutual assistance in material traffic of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances, and precursors108 | Illegal | Illegal | Anti-Drug National Committee | |

| PENDING: Framework not found | In 2001, reports of the intention to import Canadian medicinal cannabis for HIV/AIDS patients were made.109 The government registered an official request in 2002 to become a medicinal cannabis producer and exporter110 | ||||

| Central African Republic | Law No. 01.011 adopting the harmonized law relating to the control of drugs, extradition, and mutual legal assistance in the matter of illicit trafficking in narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances 111 | Illegal | Illegal | National Police (Sûreté Nationale) | |

| Chad | No framework found | Illegal26 | Illegal |

|

|

| Comoros | No framework found | Illegal112 | Illegal |

|

|

| Côte D'ivoire | Law No. 88-686, 1988, on the suppression of trafficking and illicit use of narcotic drugs103 | Illegal (Article 8) | Illegal | Police Directorate on Narcotics and Drugs | The Inter-ministerial Committee for the Fight against Drugs (CILAD) monitors impacts of legislation113 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | No framework found | Illegal | Illegal | Capital punishment is applied to certain offences28 | |

| Djibouti | Law No. 171/AN/81 on psychotropic substances114 | Illegal | Illegal | Directorate of Drugs and Pharmacy | The drug law system makes use of constitutional and Sharia law. Under Sharia law, cannabis is categorized as ‘mukhaddirat,’ referring to a substance that numbs the senses and slows the user, but use is justifiable for medicinal purposes115 |

| Egypt | Act No. 122 of 1989 amending Law No. 182 of 1960, control of trade of narcotics and regulation of substances116 | Illegal117 | Illegal | Egyptian ANGA118,119 | Punishment for possession, use, or cultivation for any reason is imprisonment of between 3 and 15 years and a fine.116,118,119 Alternatives to prison include voluntary treatment served for at least 6 months and no longer than 3 years or the sentenced sanction period—whichever is less (Article 37)120 |

| PENDING: framework not found | Decriminalized |

|

|

In 2018, legislation was put forward, proposing that repeat offenders be referred to 3–6 months of treatment121 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | No framework found | Illegal26 |

|

|

|

| Eritrea | Penal Code of the State of Eritrea, 201534 | Illegal (Article 395) | Illegal |

|

Differences made between selling and buying for personal use, with possession being considered a “less serious” offence122 |

| Ethiopia | Drug Administration and Control Proclamation No. 176/1999123 The Criminal Code of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2004123 |

Illegal124,125 | Illegal |

|

|

| Eswatinia | The Opium and Habit—Forming Drug Act 192226 Medicines and Related Substances Control Act, 2016 (Act 9 of 2016)26 |

Illegal126 | Illegal | Medicines Regulatory Authority in conjunction with the Royal Swaziland Police Service's Drug Unit | Currently, cannabis use and cultivation for any purpose are illegal and there is no medical cannabis regulatory framework26 |

| PENDING: The production of cannabis for medicinal and scientific use regulations, 2019127 |

|

Legal | Drug Administration and Control Authority, Ethiopian Federal Police ANS | Pending legislation aims to decriminalize medicinal cannabis use and cultivation127 | |

| Gabon | No framework found | Illegal26 |

|

|

|

| The Republic of Gambia | Drug Control Act, 2003 (as amended)103 Medicines and Related Products Act, 2014128 |

Illegal | Illegal | DLEAG | Government plans are underway integrate treatment programs into the existing legislature.103 Drug Control (Amendment) Act 2014, Section 35, in relation to first-time offenders offers leniency according to amount • 0.1–150 g: fine and/or imprisonment of between 6 months and 1 year • 151–500 g: fine and/or imprisonment of between one and 2 years • above 500 g: fine and/or imprisonment of between 2 and 3 years129 |

| Ghana | Narcotics Control Commission Bill of 2017 (NCC)130 | Decriminalized | Illegal | Narcotics Control Commission (NACOC) in collaboration with the Prosecuting Unit of the Ghana Police Service and the Attorney General Department131,27 | Civil penalties, i.e., fines will be issued to offenders or if necessary, treatment referrals. Failure to pay fines, translates into a 15-month jail sentence131,27 |

| Guinea | Criminal Code of the Republic of Guinea132; Decree D/2011/016/PRG/SSG, 2011.103 Decree No. 066/PRG/SSG/94 on the creation, powers and functions of the Central Anti-Narcotics Office. Decree No. 067/PRG/SGG (1994) on the Creation and Functions of the Inter-Ministerial Committee responsible for the fight against drugs |

Illegal | Illegal | Central Anti-Narcotics Office (OCAD)18 | Provisions for related offences are made in a number of decrees in the Penal Code27,132 Inter-ministerial committees are involved in the overseeing of current policy.103 There are no protocols regarding treatment27 |

| Guinea-Bissau | Legislation on narcotic drugs (Decree-Law No. 2-B, of 28 October 1993103,133 | Illegal (Article 20) | Illegal | NDLEA18 | According to substance, distinctions are made concerning sentencing: • cannabis oil, sentencing of 2 months to a year • derivative other than cannabis oil, a sentencing of 1–6 months133 |

| Kenya | The Narcotic Drugs And Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act No. 4, 1994134 | Illegal135 | Illegal | ANU | Cannabis for personal consumption punishable by 10–20 years of imprisonment and cultivation punishable by a pre-determined fine or three times the cannabis market value and/or 20 years of imprisonment134 |

| Lesothoa | Drugs of Abuse Act 2008136; The Medicines Control and Medical Devices Control Bill 2018 Act No. 5 Drug of Abuse (Cannabis) Regulations Act of 2018137 |

Illegal138 | Illegal | Narcotics Bureau | Any mode of use is punishable by a minimum of 5 years in prison or a fine (Section 9, Drugs of Abuse Act) The Drug of Abuse (Cannabis) Regulations Act of 2018 allows for medicinal cannabis cultivation Lesotho Narcotics Bureau approved permit holders can cultivate flowerings, extract active pharmaceutical ingredients, and produce medicines; Export and import medicinal cannabis products38 |

| Liberia | Controlled Drugs and Substances Act/Drugs Enforcement Agency Act, 2014, in conjunction with Penal Law36; Medicines and Health Products Regulatory Authority Act, 2010139 |

Illegal36 | Illegal | NDLEA18,36 | Security and health parliamentary committees serve as proximal mechanisms for drug control.103 Use is chargeable with 1-year imprisonment and/or a fine. Aggravating circumstances, e.g., use in a public institution may incur greater penalties.140 Courts can request an individual to submit to treatment9 |

| Libya | Law No. 7 of 1990 on Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (as amended)120 | Illegal | Illegal | Libyan Anti-Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances Agency | Offenders maybe remanded to a treatment facility for 6 months to 1 year A distinction is indicated between possession and actual use, although both are punishable with a 2-year prison sentence84 |

| Madagascar | Law No. 97-039 on The Control of Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances, and Precursors141 | Illegal (Article 140) | Illegal | The National Gendarmerie's Anti-narcotics Office142 | Article 411: Unlawful purchase, possession, or growing for personal consumption are punished as follows: • cannabis plant, including oil: 3 months to a year imprisonment and a fine • derivatives other than oil: 2–6 months of imprisonment and/or a fine Exemptions made in cases of minors or first-time offenders142,143 |

| Malawia | Dangerous Drugs Act (1994)144 Cannabis Regulation Act, 2020145 |

Illegal146 | Legal | Pharmacy, Medicines and Poisons Board | The law excludes the use of any seed crushed or processed to prevent germination; or the fixed oil obtained from the seed. Medicinal cannabis products are available to “Qualified patients” (individuals with specific medical conditions and recommendation for use) with Valid rIC obtained from the CRA.42 Cannabis Regulation Act, 2020, also legalizes medicinal cannabis cultivation |

| Mali | Law No. 01-078, 2001 on the control of drugs and precursors103 | Illegal | Illegal | Central Office of Narcotics-(OCS)55,31 | Illegal use and cultivation are sanctioned by 6 months to 3 years and 5–10 years of imprisonment, respectively, and/or a fine.27 Sentences maybe forgone for detoxification programs.103 A specialized committee monitors drug control, policies, and proposed legislation27 |

| Mauritania | Law No. 93-37, 1993103 | Illegal | Illegal147 | National Office for the Fight Against Drugs and Psychotropic Substances18 | Use is punishable with a 2-year maximum prison sentence and a fine. Standard penalties will not be applied when a user has been “successfully subjected to a cure”103 |

| Mauritius | The Dangerous Drugs Act, 1986 (as amended)64 | Illegal | Illegal | Pharmacy Board, Ministry of Health, and Quality of Life, Mauritius Police Force's Anti-Drug and Smuggling Unit | The 2000 Dangerous Drugs Act sanctions drug use with maximum 2 years of imprisonment and/or a fine148 |

| Moroccoa | Law No. 1-73-282 of May 21, 1974, on the suppression of drug use and drug prevention47 The Criminal Code of Morocco PENDING51: Framework not found |

Illegal | Illegal | Central Unit to Fight Drugs (UCLAD) | Possession or use is liable to imprisonment of between 2 months and 1 year and/or a fine.60 Article 8 of the Law on the Suppression of Drug use sets out the possibility of treatment,149 i.e., mandated medical detoxification (with a 15-day follow-up drug screening)103 National Commission on Narcotic Drugs addresses policy and coordination matters150 The Parti Authenticité et Modernité (PAM) and Rifan Deputies of the Istiqlal Party in 2013 formally proposed medical cannabis use legislation, but hashish production is not mentioned.4,61 A national agency is to be established to oversee supplying of pharmaceutical companies, seed importation, and distribution51 |

| Mozambique | Regulations for the Practice of Pharmacy, 1941,151 | Illegal151,152 | Illegal | Pharmaceutical Department, Ministry of Health | |

| PENDING: Anteprojecto de Revisão da Lei No. 3/9728 | Decriminalized (Article 36) | Legal (Article 34) |

|

Would allow only authorized possession and cultivation of small amounts | |

| Namibia | Combating of the Abuse of Drugs Bill, 2006,153 Medicines and Related Substances Control Act, 2003154 |

Illegal155 | Illegal | Medicines Regulatory Council | Section 17 of the Medicines and Related Substances Control Act, 2003, applications can be made to have cannabis or extracts of such registered as medicine.156 Use and possession are punishable with between 20 and 40 years of imprisonment and/or a fine. Cultivation is punishable with 20 years for a first conviction and at least 30 years for subsequent convictions153 |

| Niger | Ordinance No. 99-42, 1999103 | Illegal | Illegal | Coordination Centre to Combat Drugs (CCLAD) | Addicts maybe court ordered to undergo treatment, education, or rehabilitation. (Article 115)103 |

| Nigeria | The Dangerous Drugs Ordinance of 1935157 The Indian Hemp Decree No. 19 of 1966 (as amended)158 NDLEA Act No. 48 of 1989 (as amended)159 |

Illegal157,160 | Illegal158 | NDLEA161 | Possession and cultivation are punishable under the Indian Hemp Act with the later receiving imprisonment for at least 21 years158 The Indian Hemp Act of 1975 abolished the death penalty and reduced use and possession charges to 6 months of prison and/or a fine.19 Minors can undergo court-ordered treatment as an alternative103,161,162 |

| Republic of Congo | No framework found | Illegal26,163 | Illegal26 |

|

|

| Rwandaa | Law No. 03/2012 of February 15, 2012, governing narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances, and precursors in Rwanda,164 in conjunction with the N° 01/2012/OL of 02/05/2012 Organic Law instituting the penal code |

Illegal | Illegal | RNP, ANU | As of October 2020, guidelines for cultivating, processing, and export of medicinal cannabis solely for foreign markets were approved165 |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | No framework found | Illegal26,166 | Illegal26,166 |

|

|

| Senegal | Law No. 97-18, 1997,103 Drug Code (Code des Drogues)37 |

Illegal | Illegal | Central Office for the Suppression of Illicit Drug Trafficking (OCRTIS) | |

| Seychellesa | Misuse of Drugs Act, 2016167 Misuse of Drugs (Cannabidiol-based products for medical purposes) Regulations, 2020168 |

Decriminalized | Legal | NDEA | The law makes a distinction between a user and a dependent person with the latter the objective being to make treatment accessible. Patients must present the following: • a “qualifying medical condition • a prescription issued by medical practitioner; as approved by Public Health Authority, Seychelles Medical and Dental Council and the Health Care Agency.169 Unsanctioned use of medicinal cannabis, is punishable by imprisonment no longer than 6 months and a fine |

| Sierra Leonea | The National Drugs Control Act, 2008,103 Pharmacy and Drugs Act, 2001,170 Guideline for the Cultivation and Processing of Medical Cannabis (2019)171 |

Illegal172 | Illegal | NDLEA | Section 50 of the Pharmacy and Drugs Act, 2001, legalizes cultivation of cannabis for medicinal purposes |

| Somalia | Act No. 46 of March 3, 1970, concerning the production of, trade in, and use of narcotic drugs173 | Illegal | Illegal | Central Narcotics Bureau | |

| South Africaa | Medicines and Related Substances Act (Act 101 of 1965)174 Guidelines on the Cultivation of Cannabis and Manufacture of Cannabis-Related Pharmaceutical Products for Medicinal and Research Purposes |

Decriminalized | Legal | South African Police Service's Narcotics Bureau (SANAB) | A 2018 Constitutional Court ruling decriminalized adult use, possession, or cultivation of cannabis in private for personal consumption,175,44,176 allowing the amendment of provisions of Medicines and Related Substances Act No. 101 of 1965 and the Drugs and Drug Trafficking Act No. 140 of 199260 |

| PENDING: Cannabis for private purposes bill, 2020177 | South Africa Health Products Regulatory Authority | The Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill, 2020, proposes as follows: Public consumption is illegal and liable to 2 years of imprisonment.178,179 Patients require valid prescriptions from a licensed practitioner to access medicinal products for the following eligible conditions: • Severe muscle spasms or pain in patients with multiple sclerosis; • Severe nausea, vomiting, or wasting arising from cancer, HIV/AIDS; • Severe epileptic seizures where other treatment options have failed or have intolerable side effects; • Severe chronic pain conditions45,94,180–182 |

|||

| South Sudan | Drug and Food Control Authority Act, 2012183 The Penal Code Act, 2008184 |

Illegal | Illegal | SSNPS | |

| Sudan | Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1994 | Illegal | Illegal. (Article 20-1) | SPF | Use and cultivation are punished by no longer than 5 years of imprisonment and a fine; charges are terminated for undergoing voluntarily treatment (between 6 months and 2 years)84 |

| Togo | Drug Control Law No. 98-008, 1998103 | Illegal | Illegal | Central Office for the Suppression of Illicit Drug Trafficking and Money Laundering18 | Possession and cultivation of small quantities are punishable with lesser penalties. The penalty for cultivation and production of cannabis oil is 2 months to 1 year; 6 months for any other plant derivative and/or a fine.185 Treatment is alternatively offered instead of prison103 |

| Tunisia |

Law No. 92-52 of May 18, 1992 on Narcotic drugs (as amended)84 Law No. 2017-39 dated May 8, 2017, amending Law No. 92-52 dated May 18, 1992, related to narcotics186 |

Illegal | Illegal | National Narcotics Bureau (Bureau National des Stupéfiants)95 | Actual or attempted consumption or possession sanctioned by imprisonment of between 1 and 5 years and a fine.84 Cultivation can receive a 6–10-year sentence with a fine9 Law No. 2017-39 states article 53 of the penal code is not implemented regarding narcotics infringements,186 giving judges the right to reduce related penalties.147,187,188 The Narcotics Commission, an auxiliary body in policy implementation, has the authority to compel addicts to undergo treatment95 |

| Uganda | The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act, 2015189 | Illegal116 | Illegal | NDA | Possession and use are liable to a fine and/or 1–5 years of imprisonment.26 The Act empowers the Minister of Health to establish rehabilitation centers83 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | The Drug Control and Enforcement Act (CAP. 95), 2016,190 The Tanzania Food, Drugs And Cosmetics Act (CAP. 219)191 |

Illegal | Illegal | DCEA | Possession or use is punishable with 1–5 years of imprisonment, or a hefty fine for small amounts. Small quantities are classified as follows: • cannabis plant <50 g • cannabis resin or oil <5 g The onus falls on the individual to prove intent not being for sale or distribution for larger quantities190 Engagement in cultivation (which includes gathering) is liable to imprisonment of not <30 years. Related activities may be conducted only on the account of government192 |

| Zambiaa | Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1993,193 The Dangerous Drugs Act, 1965194 |

Illegal123 | Legal (Section 18 Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act Cap 96) | Drug Enforcement Commission | Use is recognized in cases of chronic pain, nausea caused by treatments such as chemotherapy, epilepsy, glaucoma, and sclerosis symptoms.87 Cultivation is legal solely on the basis of medicinal use and not on a commercial scale195 |

| Zimbabwea | Chapter 15:02 Dangerous Drugs Act (as amended) in conjunction with the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act [Chapter 9:23] Act 23/2004 Statutory Instrument 62 of 2018. [CAP. 15:02] Dangerous Drugs (Production of Cannabis for Medicinal and Scientific Use) Regulations, 2018196,197 |

Illegal.41,199 | Illegal | Ministry of Health and Child Welfare and the ZRP41,199 | Statutory Instrument 62 of 2018: Authorized individuals can cultivate and produce medicinal cannabis products40 |

Information not available.

Information not available.

Countries with medicinal cannabis-specific provisions.

ANGA, Anti-Narcotics General Administration; ANS, Anti-Narcotics Service; ANU, Anti-Narcotics Unit; CCLAD, Coordination Centre to Combat Drugs; CILAD, Committee for the Fight against Drugs; CNLD, National Committee to Combat Drug Abuse; CRA, Cannabis Regulatory Authority; DCEA, Drug Control and Enforcement Authority; DLEAG, Drug Law Enforcement Agency of the Gambia; NACOC, Nation Control Commission; NCC, Narcotics Control Commission; NDA, National Drug Authority; NDEA, National Drugs Enforcement Agency; NDLEA, National Drug Law Enforcement Agency; OCAD, Central Anti-Narcotics Office; OCRTIS, Central Office for the Suppression of Illicit Drug Trafficking; OCS, Central Office of Narcotics; PAM, Modernity and Authenticity Party; rIC, registry Identification Cards; RNP, Rwanda National Police; SANAB, South African Police Service's Narcotics Bureau; SPF, Sudan Police Force; SSNPS, South Sudan National Police Service; UCLAD, Central Unit to Fight Drugs; ZRP, Zimbabwe Republic Police.

Recreational policies

Of the 54 countries, we identified provisions for 46 countries. Provisions for Burundi, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon and Sao Tome and Principe were not made accessible through our method. Continentally, cannabis is illegal with the major differences seen in the degree of imposed sanctions, which, dependent upon country and circumstance, can be a fine and/or sentencing ranging from 2 months to death penalties. Ghana, Seychelles, and South Africa have decriminalized personal use, with South Africa allowing private cultivation. Egypt and Mozambique have pending decriminalization legislature.

Most countries lack independent bodies tasked with policy implementation and data collection.25 Enforcement efforts are undertaken by a combination of authorities, including health departments, interministerial committees,27 civil society organizations (CSOs),28 prison services, and community-based initiatives.29 The extent to which imprisonment alternatives (fines and treatment) are used is limited. Arrested individuals face lengthy detentions and are often neglected following conviction.30

Treatment, education, and rehabilitation facilities are scarce, underfinanced, and non-existent in countries such as Sierra Leone and Liberia.30 In the former, 32 mentally ill youths were arrested and sentenced to prison in 2015 for possession due to the absence of facilities.30 Malian law grants treatment to convicted users, but fails to detail treatment guidelines.31 Burkina Faso's Drug Code references therapeutic injunctions for users, but fails to assign accountable entities.32 The Gambian government revealed construction plans in 2020 for a cannabis rehabilitation center to fulfill legislative provisions.33 Guinea,31 Eritrea,34 Ethiopia,35 Liberia,36 Morocco, Rwanda,29 Senegal,37 South Sudan, and Zimbabwe include regulations into penal legislation, setting precedence to criminalize users.

Medicinal policies

According to the literature, seven countries (Lesotho, Malawi, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) have made official medicinal cannabis-specific provisions and 4 countries (Eswatini, Cameroon, Morocco, and South Africa) have pending legislation. Of the official legislation, provisions are mainly for medicinal cultivation for export. South Africa, Seychelles, and Malawi have established medicinal cannabis programs for patients to access medicinal cannabis.

In 2017, Pharmaceutical Development Company Ltd. became the first company in Lesotho and Africa, licensed to carry out legal cannabis activities.38,39 In Eswatini, American company, Profile Solutions, stands to become licensed to operate a medical cannabis facility for a 10 year minimum.8

In Zimbabwe (March 2019), Precision Cannabis Therapeutics was approved for a USD$46,000 cultivation license along with water rights to a dam40 and partner companies Eco Equity, DutchGreenhouses, and Australian Delta Tetra were approved to construct a medicinal cannabis greenhouse.41 Malawian companies, Invegrow and IKAROS, are licensed producers of “organic” essential oils42 and hemp extracts.43 Holistic Relief Wellness and Pain Management Centre became the continent's first dispensary offering infused Cannabidiol products,44 including Dronabinol.45

Although no official announcement from the Democratic Republic of the Congo government has been made, in 2017, Canadian company, EXMceuticals, became licensed to grow psychotropic cannabis.8 A similar occurrence is presented in Uganda where, despite no published regulations, companies have received approval to conduct related operations,8 but government representatives announced, in 2019, official plans to issue licenses.46

Policy impacts

Direct

The following are in reference to recreational policies, as African medicinal policies are developing. Gauges of drug policy effectiveness47 include plantation eradication, facilities closures, seizures and arrests, use trends, and health effects.18

Continentally, between 2010 and 2018, cannabis seizures increased by 53%.48 However, the Nigerian NDLEA Annual Report (2016) showed a decline in related arrests and seizures, despite cannabis topping the list of drugs seized (187,394 kg from a 267,591.49 kg drug total) and 718 ha of plantations eradicated.25 In Senegal, quantities seized from 2000 to 2009 included 45.08 t cannabis and 13.78 t hashish.49 Rwanda reported tracking 2890.179 kg and arresting 1671 people in 2009, and in January of the following year, 563,988 kg had been seized and 999 people arrested.50 Algerian security services seized 56,548 plants between 2003 and 2018, primarily from multihectare plantations.51 Morocco's resin industry still produces similar quantities as it did decades ago.51

An American research institute's regional report on the state of the continent's cannabis market produced the following statistics as of 2019: 83 million or nearly a third of the world's 263 million users are in Africa; Nigeria has the highest number of users at 20.1 million followed by Ethiopia (7.1 million); Africa's estimated market accounts for 11% of the total global market; and the continental consumption rate (11.4%) is twice that of the global rate (6%).26

The 2020 UNODC World Drug Report identified West and Central Africa as Africa's “epicenter of cannabis use,” with a 9.3% estimated annual prevalence among adults compared to the global and continental average of 3.9% and 6.3% respectively; North Africa's annual prevalence was 5.1% (Morocco's numbers are rising with 600,000–800,000 users, Algeria and Tunisia have roughly 200,00051); East and Southern Africa survey data were unavailable, but countries within the regions reported increased use between 2009 and 2018; and between 2010 and 2018, the following had comparably significant cultivation and/or production: Morocco (47,500 ha), Nigeria, Eswatini, Sudan, South Africa, Malawi, Zambia, DRC, Lesotho, and Ghana.48

Cannabis is commonly smoked, processed into a paste, or distilled into oil for incorporation into foods and beverages or mixed with cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin, and methaqualone.52 In West Africa cannabis, alcohol and diazepam/trihexyphenidyl are typically combined.49 Synthetic cannabinoids are gaining popularity, particularly in Mauritius53 where they are available as a powder mixable with tobacco for smoking or dissolved in a solvent (thinner or acetone) sprayed on low-quality cannabis.28

In terms of health consequences, 12–40% of youths in psychiatric hospitals across Africa were diagnosed with cannabis or drug-induced psychosis.52 Ghanaian health providers expressed belief in the “gateway theory” (cannabis consumption leads to harder drugs).54 Drug use disorders were highest among people between 15 and 44 years of age, with primary or secondary education, and who were unemployed, with cannabis the primary drug of choice for treatment seekers according to the West African Epidemiology Network55 and the Pan-African Epidemiology Network.56

According to research, 50% of Zimbabwean mental institutions' admissions have been attributed to substance misuse, with 80% of those patients primarily being male between 16 and 40 years of age.57 In South Africa, indicators associated with disorders in males included younger age, mixed race, urban area residency, and violent crime victims, while for females, younger age, being white or mixed race, being unemployed, and psychological distress were associated factors.58

Indirect.

Environmental

A UN resolution suggested increased cultivation has accelerated soil erosion, primarily due to excessive fertilization, soil overexploitation, forest destruction, and eradication efforts.59 In 2015, South African Police Services used helicopters to spray herbicides on rural cannabis subsistence farms with no regard to crops, livestock, or rivers, potentially exposing people to contamination.60 Increased cultivation and poor soil conservation have taken a toll on the Rif,61 posing a severe ecological and social risk.12 Anecdotal evidence suggests declining yields and size are likely a result of limited crop rotation and continual monocropping as seen in 17% and 36% of fields in Botsoapa, Lesotho, respectively.59

Soil infertility has a corresponding impact on licit crops yields leading to greater demands for larger land areas to maintain output.62 Environmental overexploitation by a rapidly expanding population and increased cannabis production can led to decreased food production and subsequently poorer nutrition due to increased food costs.12,59 New hybrid varieties requiring more water to reach maturity pose a risk to water resources and their increased use in Morocco risks the future of licit and illicit economic development due to depleting aquifers.51

Economic and socioeconomic stability

South Africa's war on cannabis cost tax payers over USD$223.7 million in 2014 and 2015 through arrests and other reduction activities.60 Africa's agrarian-based image and donor reliance within and out of drug control dialogs influence policy execution.59,63 Aid directed at illegal drugs, shaped by individualized plans, often tries to extend enforcement,2 for example, internationally backed West-African strategies have overlooked domestic use, concentrating on preventing exportation.54 Western-funded eradication campaigns in Morocco cost 75 million Euros between 2003 and 2013.47

Cost–benefit analysis of Mauritius's drug policy found, in 2014, government expenditure on repression and health services took up 78% and 22% respectively, of the Rs300,909,835 budget for combating drugs.64 Ethiopia's 2017 national drug control budget was USD$980, 000, of which 34.2% (USD$335,000) was for demand and harm reduction.65

In Lesotho, the crop is the only source of livelihood for some because of high unemployment.66 In the Rif, the situation is similar and some producers who have even been able to gain wealth far exceeding expectations, continually fight for their right to cultivate.67 Moroccans view production differently from organized crime due to little associated violence and authorities not focusing on the issue.51 Northern Nigeria wholesalers credited their financial successes to cannabis's profitability and capacity to withstand economic downfalls.68 Poor government services can influence public demand as illustrated by Zimbabwean rural farmers who unsuccessfully attempted to legalize cannabis they grew for traditional medicinal uses due to frequent medication shortages.8

The Rif region depends on hashish for socioeconomic and political stabilization,12 with profits considered important to maintain social balance.61 Industry revenues are reinvested in uncontrolled housing development, particularly in northern Morocco.61 The growing number of drug users in Ghana is partly a reason behind the expansion of ghettoes.49 Stricter policies could cause more illegal immigration of Africa's youth, weakening communities and delaying development. The cannabis economy, in this sense, regulates employment and emigration.12,51 Young Rif farmers driven by poverty have left areas that are frequently targeted by law enforcement for other Moroccan regions and Europe.12

Associated crimes

Trafficking is mainly intraregional, with the most frequently reported countries of origin, departure, and transit, between 2014 and 2018, by region and in order of importance being as follows:

West and Central Africa: Ghana and Nigeria; Southern Africa: Mozambique, Eswatini, and Malawi; East Africa: Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya; and North Africa: Morocco.48 Even so, in Ghana, low arrests and convictions are attributed to legal corruption.49 Contrastingly, in 2009, the Moroccan Court of Appeal for the first time convicted 109 people, charged with arranging a criminal group and international drug trafficking.61 Despite this, it is understood by producers who engage local officials with payments as bribes to ignore their activities that this relationship is fundamental to sustaining the trade.51

By weight and value, cannabis is the most trafficked drug from and through the Maghreb with small streams of product entering from West Africa or the Levant.51 Globally, Morocco is the most frequently mentioned resin primary source as identified in more than a fifth of all instances between 2014 and 2018.48 Trafficking has introduced foreign elements, that is, Afghani and Lebanese opium-laced hashish have reportedly become available for purchase to Libya's smokers.69

West-Africa is labeled as an emerging transiting station, as proven reinforced by a causal relationship between international trafficking and terrorism.18,70 In Mali, trafficking has been found to be involved within governing structures, militarizing Sahel forces, undermining peacekeeping efforts, and official governance legitimacy.31 Congolese social narratives have redefined cannabis into a rebel tool for encouraging killings and sexualized violence.6 In Benin, the trade is considered a growing threat, believed to finance political corruption.49 Southern Africa's forecasted cannabis market expansion maybe affected by actions taken against and in response to organized crime, for example, Nigerian networks trafficking cannabis from the region.71

Despite being nonperishable, fear of being caught with cannabis and failure to take advantage of the trading season cause farmers to oversupply markets, devaluing their commodity.7 This forces Congolese traders to cross dangerous terrains like the Ruzizi's crocodile-infested waters to reach Burundi markets, the greatest danger often occurring during encounters with soldiers.7 As traders and growers are operating illegally, they are unable to appeal for protection in cases of abuse from local enforcement.

The illegality of the trade, the need to conceal activities, and demand can lead to black market creation; “policy displacement,” through redirecting resources to law enforcement; the “balloon-effect,” whereby enforcement shifts drug production and supply elsewhere; “substance displacement,” whereby enforcement measures lead users to consuming other substances, for example, in Mauritius, increased actions against cannabis have made it scarce and expensive (USD$35–USD$75/g), making more hazardous synthetic cannabinoids a more accessible alternative at USD$15/g; and stigmatization discouraging users from accessing treatment.28

Enforcement and incarceration

Users are depicted as criminals and wayward,72 as in Gambia, cannabis is considered responsible for most drug-related crimes.73 In South Africa, this perception is fueled by car hijackings by smugglers and crimes by users to fund their consumption.59 Fear and insecurity were common themes mentioned, explaining individuals' experiences when in the presence of users.74 Perceptions of users are based upon sociocultural norms, with religiosity cited as the greatest deterrent to cannabis engagement.6 Nigerian reports indicate high degrees of public concern, with use identified as a loss of morality leading to psychosis.75 Similar generalizations are made in Ghana, as users are perceived as defective and unlikely to regain a state of normalcy.54

Structural violence (beatings and unwarranted arrests) was indicated as the most common form of enforcement, with persistent surveillance and crackdowns also used by authorities as means to generate income through bribery and fulfill arrest quotas.20 Congolese Pygmies are constantly challenged by such because of cultivation in an area once considered their hunting grounds until state backed evictions.76

Nigerian users described a consequential sense of fear from enforcement tactics considered personal infringements.20 Users defend cannabis as an aid for ailments, focus, and sexual potency,2 nonetheless, reported the importance of concealment.72 Post-conflict Liberians referred to use for performance enhancement during conflict, but more so to deal with psychological trauma.77

Nigerian health professionals acknowledged the existence of government institutions, but stated cost and limited facilities as the biggest impediments to receiving help.78 Users in Dodoma, Tanzania, reported unawareness of treatment options.79

Due to limited facilities and perceptions that drug disorders are religious manifestations, pseudo-treatments are common.32 Churches, traditional doctors, and prayer camps are typical first-line treatment in Ghana, with most users at government institutions previously having undergone a form of religious treatment.30,54 Psychiatric hospitals and faith-based facilities are overcrowded and underfunded, and lack qualified personnel.31 Critics of Ghana's drug decriminalization consider the inability to provide quality treatment disadvantageous to the measure.54

West Africa's drug-related arrests increased during 2014–2017, with ∼16,000 arrests in 2017 with Cabo Verde, Gambia, and Nigeria reporting the highest numbers.32 Between 2011 and 2014, Mauritius witnessed a 78% increase of cannabis-related convictions, despite prison services reporting a 48% drop in drug detainees from 2005 to 2013.64 In Senegal, it is estimated that a quarter of the overcrowded prison population are drug users.49 Tunisian prison system's official capacity is roughly 18,000, but estimates note that facilities are operating at 150–200% capacity.9,80 Roughly one-third of the population are facing or serving drug-related sentences, and in 2016, over 56% of drug use detainees were caught in possession of cannabis,62,81 but following policy amendments, prisoners have reportedly decreased.82 Ghanaian overcrowded prisons are characterized by a considerable segment of convicts on drug-related charges.49

Incarcerated users are often exposed to more lethal drugs as proven by emerging drug injecting trends in Ugandan prisons.83 In Côte d'Ivoire, correctional facilities' requests for rehabilitation have increased, as convicts admit to consuming varieties of drugs, although admittedly before imprisonment solely used cannabis.32 Imprisonment has been related to high economic expenditure, social stigmatization, expansion of extremist gangs, and smuggling networks.9,83

Prospects for change

West Africa Commission on Drugs and West Africa Drug Policy Network advocate for drug policy reform in West Africa, with the former carrying out policy training in collaboration with local institutions,28 and the latter, in calls for drug decriminalization,84 focuses on local CSOs capacity building to address impacts on governance and health.26

Fields of Green for All, a South Africa-based organization, hosts conferences, notably Clinical Cannabis Convention Conference, addressing drugs in relation to rights and reform.28 Kenya's Africa Cannabis Association actively seeks to pressurize the government by encouraging the National Assembly to legalize cannabis, protect farmers, and change attitudes.26 Human rights groups have endorsed further reformation of the modified Tunisia's Law 52, currently seen as an interim solution.9 Industries with potential stakes, such as tobacco companies with technical skills and finances, may possess the greatest policy-influencing ability.43

The global legal and illicit cannabis market is valued at USD$344.4b, with Africa's share at 11% (USD$37.7b).85 Based on the markets of South Africa, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Nigeria, Morocco, Malawi, Ghana, Eswatini, and Zambia, Africa's legal market could, by 2023, be worth over USD$7.1b.26 Nigeria ranks first in terms of market potential (USD$15.3b), and then Ethiopia (USD$9.8b).85

Legalization may lead to government gains.74 Income from previously decentralized and undocumented transactions in countries such as Morocco, with about 800,000 growers and cultivators in the trade, could possibly generate annual sales estimated at USD$10b, as the current illicit industry accounts for nearly 10% of its gross domestic product.5 Huge opportunities exist along the value chain, for example, equipment supplying for industrialization and employment creation.86 Increased European demand, which is driving licit markets, could lead to foreign currency influx.47 Decriminalization alleviates pressures on the penal system and related costs. Nigeria's underutilized pharmaceutical sector currently operates at roughly 40% and could be a key industry for medical cannabis due to its reliance on imported pharmaceuticals.26

Sustainability of “alternative development” relies on programs being of comparable economic value to discourage illicit trading.35 Licit cash crops' prices are considerably lower than those of cannabis.12 In Congo, 100 kg cannabis sells for up to USD$128, far more than USD$54 for maize.26 Year-round cultivation in Eswatini can yield a domestic retail price/mt return of USD$43,300 compared to USD$400 for sugar and USD$175 for maize.5

Financial challenges, value imbalances, and favorable production climate mean that Africa could become economically reliant on cannabis as a main financial source.68 Since 2013, pressures from Zambia's financial debt (USD$10.5b in 2018)87 have encouraged major political party, the Green Party, to promote cannabis exportation.88 Malawi is one of the most tobacco-dependent countries,89 estimating half of all foreign earnings generated from sales.43 Declining productivity has motivated officials to believe cannabis legalization will lead to diversification.42

Discussion

Prohibitive measures aiming to minimize availability are the norm.65 Related activities are subject to criminalization, partly due to policies shadowed by outdated research and colonialism. Ghana, Seychelles, and South Africa have taken into consideration the human rights violations imposed by policies and decriminalized personal use.

Continentally, drug use is becoming increasingly common and a greater health-related problem.90 Trends indicate that negative impacts are on a continental rise; however, because of a lack of population-based data, most is sourced externally and may not represent the true situation.18 As of 2019, there are an estimated 263 million users, largely young males without regular income. This may be explained by cannabis's comparatively low selling price, being locally sourced, early-age initiation,91 and low quit rate.74,92 Poverty, unemployment, and unfavorable social conditions also favor use, particularly among a increasing youth population.

Reported seizures have been declining. This may be due to mainly intraregional trafficking. Regional security forces may be more willing to ignore illegal activities and lack appropriate resources. Benin security services suggested that the decrease could be down to better skilled traffickers assisted by corrupt officials.49

Declining seizures have not translated into a decrease in users and growers as evidenced by an increasing prison population of drug-related convicts (mostly charged with cannabis possession) and growing treatment demands.49 Even so, Morocco has maintained resin production levels owing to unwillingness to enforce policy, a dynamic created by eradication attempts that contributed to social unrest, leading authorities to instead choose to use containment strategies.61 Despite decades of prohibition, intentions to limit access have remained elusive. Corruption, lack of control bodies, and poor regional dialog have been reported as causes for reporting inconsistencies.31,51

Medicinal cannabis interests have resurged in the past decades. African countries have created provisions for access and cultivation. A commonality exists, most laws appear directed toward foreign export markets rather than providing health and financial alternatives.93 Licensing fees and international operating standards are beyond the reach of locals88 and likely only achievable for foreign investors.94 This can lead to criminal syndicate development to participate in activities such as money laundering.88

South Africa and Seychelles stand out by having regulations for patients to access cannabis. We can only infer impacts of medicinal policies, given limited data. These may range from job creation and health research sector development to further increasing the wealth gap and local market underdevelopment.

Implications for future policies

By contrast with tobacco and alcohol, cannabis use and associated outcomes tend to be undervalued due to the lack of reliable documentation studies95 as well as the largely ignored, misunderstood, and generally taboo nature of use, usually due to political and social denial.96 For instance, in Ghana, the result of this underreporting is that the number of female users has been vastly underrepresented, which means that their treatment needs are largely unmet.54 Studies have suggested a connection between prevalence of cannabis use and of existing policies. Prevalence is typically measured in three ways: ever used, used last year, and used last month.

Figures currently indicate an increase in prevalence of cannabis use and associated psychosis in Africa. However, longitudinal and internationally comparable information on these measures are lacking for African countries. Given so, establishing comparable data across many African countries complicates the analysis process of the policy-prevalence relationship. Within Africa, most data are provided by international studies that do not provide in-depth situational analysis and may therefore be misleading or underreported. Therefore, interpreting differences and similarities across policy regimes must be done understanding the ununiform nature of data backing the policies. The African Union's Specialised Technical Committee on Health, Population and Drug Control may devise coherent strategies to monitor indicators.

Variations exist in formal policy among nations. A great distinction exists between formal policy and actual implementation in a number of countries or jurisdiction, for instance, in Morocco's Rif region. Several influences contribute to the discrepancy of uniform policy implementation, one of particular relevance to the African context is the allocation of enforcement. This study revealed that most regulatory authorities, when they do exist, operate under discretionary authority of the law and judiciary system, which often relies on punitive approaches of enforcement. Independent autonomous bodies are more practical; however, human and monetary resources often limit their capacities.

Greater punitively designed policies are linked to greater criminalization; however, be it from evasion, to bribery, to corruption, the two do not linearly correlate. Nonetheless, users and growers who are criminalized bear the burden of experiencing the penal system even after release. Social consequences faced by actors in the trade include stigmatization, loss of employment, loss of civil privileges, and relationships. Government expenditure on law enforcement, creation of black markets, and crime negatively impact the community at large. The full extent of these consequences has not been fully examined in an African setting in terms of their impacts on economic and social development and effectiveness of deterring others.

Limitations

Results are to be interpreted with the understanding that findings were largely dependent upon the methodology used, which extensively relied on the accessible electronic databases and resources. In this way, the reporting of impacts may be biased and demonstrate more negative outcomes owing largely to long existing prohibitive nature of policies. Although most reported impacts of cannabis policies are presented negatively, positive impacts are heavily reliant on anecdotal evidence typically stemming from engagement in the extralegal cannabis economy (i.e., a criminalized network that stretches between formal political actors and those engaged directly in the cannabis trade59). Key examples of this include Lesotho and Morocco.

As policies are changing, it will be important to investigate how more liberal regulations benefit or disadvantage locals particularly in the aforementioned settings, where the plant is de-facto decriminalized and acts as a medical panacea as well as a major source of household income, even considered more reliable than the prospect of waged work.

This method was also unable to identify regulatory provisions for all-inclusive countries; therefore, to be able to provide more comprehensive and current information, further research may require incorporation of regionally and locally available unpublished resources not indexed on commonly used databases (e.g., books, dissertations, anecdotes, and nonelectronic government reports often only available in the relevant countries). Results cannot be generalized to all nations, but they stand as an identifiable point for further research, and policy information can be continually updated as more information is made accessible.

Conclusion

Cannabis framework is a complex issue handled under a series of policies and characterized by a range of contributing factors. Our study was able to identify information on policies' statuses for most countries, but even so, most information did not provide a full picture of regulatory environments (e.g., regulatory authorities and measures, prevalence measures, and society impacts). Countries with long standing cannabis histories or recent changes in policies were mainly reported upon and provided the bulk of information for this study.

Investigation of underrepresented nations and communities may help better explain the current significance of cannabis and the societal benefits and constraints that policies place on its usage, and more importantly on the general public. Policy changes based on modern trends should include larger study of previous policy impacts and future-oriented analysis of country-level goals incorporated with a greater understanding of public opinion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express gratitude to our technical support team.

Abbreviations Used

- ANGA

Anti-Narcotics General Administration

- ANS

Anti-Narcotics Service

- ANU

Anti-Narcotics Unit

- CRA

Cannabis Regulatory Authority

- CSOs

civil society organisations

- DCEA

Drug Control and Enforcement Authority

- DLEAG

Drug Law Enforcement Agency of the Gambia

- NDA

National Drug Authority

- NDEA

National Drugs Enforcement Agency

- NDLEA

National Drug Law Enforcement Agency

- PAM

Modernity and Authenticity Party

- rIC

registry Identification Cards

- RNP

Rwanda National Police

- SPF

Sudan Police Force

- SSNPS

South Sudan National Police Service

- UN

United Nations

- UNODC

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- ZRP

Zimbabwe Republic Police

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary Material

Cite this article as: Kitchen C, Kabba JA, Fang Y (2022) Status and impacts of recreational and medicinal cannabis policies in Africa: a systematic review and thematic analysis of published and “gray” literature, Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 7:3, 239–261, DOI: 10.1089/can.2021.0110.

References

- 1. ElSohly MA, Radwan MM, Gul W, et al. Phytochemistry of Cannabis sativa L. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod. 2017;103:1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carrier N, Klantschnig G. Quasilegality: Khat, cannabis and Africa's drug laws. Third World Q. 2017;39:350–365. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonini SA, Premoli M, Tambaro S, et al. Cannabis sativa: a comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long history. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;227:300–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adu-Gyamfi S, Brenya E. The marijuana factor in a university in Ghana: a survey. J Sib Fed Univ. 2015;11:2162–2182. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eligh J. The Evolution of Illicit Drug Markets and Drug Policy in Africa. ENACT, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laudati A. Living dangerously: confronting insecurity, navigating risk, and negotiating livelihoods in the hidden economy of Congo's cannabis trade. EchoGéo. 2019. DOI: 10.4000/echogeo.17676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laudati A. Securing (in) security: relinking violence and the trade in cannabis sativa in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Rev Afr Polit Econ. 2016;43:190–205. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duvall CS. A brief agricultural history of cannabis in Africa, from prehistory to canna-colony. EchoGéo. 2019. DOI: 10.4000/echogeo.17599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blackman A. Prison reform and drug decriminalization in Tunisia. In: Blackman A, ed. Social Policy in the Middle East and North Africa. The Project on Middle East Political Science: New York, 2018, pp. 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Friedman D, Sirven JI. Historical perspective on the medical use of cannabis for epilepsy: ancient times to the 1980s. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;70:298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gazette TB. Govt on high as weed takes a hit. Available at https://www.thegazette.news/latest-news/govt-on-high-as-weed-takes-a-hit/23226/#.X4BIu0YzYal Accessed October 8, 2020.

- 12. Chouvy P-A, Laniel LR. Agricultural drug economies: cause or alternative to intra-state conflicts? Crime Law Soc Change. 2007;48:133–150. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Putri D. Cannabis rescheduling: what could it mean for Africa? International Drug Policy Consortium: London, 2020, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization. List of globally identified websites of medicines regulatory authorities. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adams RJ, Smart P, Huff AS. Shades of grey: guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. IJMR. 2017;19:432–454. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaska M, Chowdhury M, Naidu J, et al. Exploring all that is grey in the health sciences: what is grey literature and how to use it for comprehensive knowledge synthesis. JNHFB, 2019;8:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 17. van het Loo M, van't Hof C, Kahan JP. Cannabis Policy, Implementation and Outcomes. RAND corporation: Arlington, Virginia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nelson E-U, Obot I. Beyond prohibition: responses to illicit drugs in West Africa in an evolving policy context. Drugs Alcohol Today. 2020;20:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nelson E-U, Obot IS, Umoh OO. Prioritizing public health responses in Nigerian drug control policy. Afr J Drug Alcohol Stud. 2017;16:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelson EU. Police crackdowns, structural violence and impact on the well-being of street cannabis users in a Nigerian city. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;54:114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Union TA. Final Progress Report on the implementation of the AU Plan of Action on Drug Control (2013–2017) extended to 2019. The African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ethiopian Food, Medicines and Health Care Administration and Control Authority Ministry of Health. Ethiopia National Drug Control Master Plan: Addis Ababa Ethiopia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shelly S, Howell S. South Africa's National Drug Master Plan: influenced and ignored. Global Drug Policy Observatory, Global Drug Policy Observatory, Working Paper No. 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24. International Narcotics Board. INCB Report 2019: Chapter III—Africa. International Narcotics Board: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Drug Use in Nigeria. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prohibition Partners. Africa Cannabis Report. Prohibition Partners: Washington, DC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27. West African Commission on Drugs. Harmonizing Drug Legislation in West Africa—A Call for Minimum Standards. West African Commission on Drugs: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa. Don't Treat us as Outsiders Drug Policy and the Lived Experiences of People Who Use Drugs in Southern Africa. AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA): Windhoek, Namibia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gonis GI. Illicit drugs use among youth: a hindrance to socio-economic development in Rwanda. Social Research Reports, Expert Projects Publishing House, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gberie L. Invisible victims: drugs, state and youth in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gberie L. Crime, violence and politics: drug trafficking and counternarcotics policies in Mali and Guinea. Center for 21st Century Security Intelligence, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the European Union. Therapeutic Injunction: a health alternative for reduced drug dependence. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Disappoint. Gambia ministry to construct rehabilitation center for cannabis abusers. Available at https://diaspoint.nl/gambia-ministry-to-construct-rehabilitation-center-for-cannabis-abusers/ Accessed October 13, 2020.

- 34. Eritrea Ministry of Justice. Penal Code of the State of Eritrea. The Ministry of Justice: Asmara, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Teshome A. The Scaffolding of Illegal Drugs Controlling and Prevention. College of Social Sciences Addis Ababa University, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36. U.S. Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. Review of the Liberian Controlled Drug and Substances Act and Liberia Drug Enforcement Agency Act. U.S. Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Assembly of Senegal. SENEGAL: Loi 2007–31 du 27 décembre 2007 portant modification des articles 95 à 103 du Code des Drogues [Law 2007–31 of December 27, 2007 amending Articles 95 to 103 of the Drug Code]. National Assembly of Senegal: Republic of Senegal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tharoor A. US Corp Cashes in as Lesotho Becomes the First African Country to Legalise Cannabis Cultivation. Available at https://www.talkingdrugs.org/lesotho-cannabis-legalisation-restricted Accessed October 16, 2020.

- 39. Biscotti C. Halo Labs Inc (OTCMKTS:AGEEF) To Acquire Bophelo After Securing Approval from Central Bank of Lesotho. Available at https://drpgazette.com/2020/07/30/halo-labs-inc-otcmktsageef-to-acquire-bophelo-after-securing-approval-from-central-bank-of-lesotho/ Accessed October 16, 2020.

- 40. Lamers M. Zimbabwe approves first license for private cannabis company. Available at https://mjbizdaily.com/zimbabwe-issues-first-license-private-cannabis-company/ Accessed October 21, 2020.

- 41. Friedman S. $40k+ Will Buy You a License to Grow Cannabis in Zimbabwe. Available at https://cbdtesters.co/2020/06/06/40k-will-buy-you-a-license-to-grow-cannabis-in-zimbabwe/ Accessed October 21, 2020.

- 42. Friedman S. Next stop for cannabis industry investors: Malawi. Available at https://cbdtesters.co/2020/06/12/next-stop-for-cannabis-industry-investors-malawi/ Accessed October 16, 2020.

- 43. Sowoya L, Akamwaza C, Matola AM, et al. Goodbye Nicky hello Goldie–exploring the opportunities for transitioning tobacco farmers into cannabis production in Malawi. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ruskin Z. South Africa's cannabis policy is wildly confusing, despite “Dagga” being part of the culture for centuries. Available at https://www.civilized.life/articles/south-africas-cannabis-policy-is-wildly-confusing-despite-dagga-being-an-integral-part-of-the-culture-for-centuries/ Accessed October 6, 2020.

- 45. South Africa Health Products Regulatory Authority. South Africa: the status of cannabis for medicinal and research purposes. South Africa Health Products Regulatory Authority: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46. The Independent. Gov't to license marijuana growing companies. Available at https://www.independent.co.ug/govt-to-license-marijuana-growing-companies/ Accessed October 20, 2020.

- 47. Bouhout N. The Failure of Global Drug Control Policy; Morocco's Cannabis Resin Market as a Case Study. School of Public Policy, Central European University: Budapest, Hungary, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49. West Africa Civil Society Institute. Towards a new approach to address drug trafficking, production and consumption in West Africa. West Africa Civil Society Institute: Accra, Ghana, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kasirye R. Drug Abuse trends, magnitude and response in the Eastern African region. Uganda Youth Development Link: Kampala, Uganda, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Herbert M, Gallien M. A RISING TIDE: trends in production, trafficking and consumption of drugs in North Africa. Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Acuda W, Othieno CJ, Obondo A, et al. The epidemiology of addiction in Sub-Saharan Africa: a synthesis of reports, reviews, and original articles. Am J Addict. 2011;20:87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Clarke H. The dark side of paradise: how synthetic cannabis is turning Mauritius' youths into zombies. Available at https://www.scmp.com/news/world/africa/article/2177143/dark-side-paradise-how-synthetic-cannabis-turning-mauritius-youths Accessed October 17, 2020.

- 54. Bird L. Domestic Drug Consumption in Ghana. Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 55. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the European Union. WENDU Report Illicit Drugs and Supply (2014–2017). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 56. The African Union. Pan-African Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (PAENDU) for the period 2016–2017. The African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Box W. Country snapshot: drugs in Zimbabwe. Available at https://gdpo.swan.ac.uk/?p=245 Accessed October 21, 2020.

- 58. Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N. Drug use among youth and adults in a population-based survey in South Africa. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2018;24:1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bloomer J. Using a political ecology framework to examine extra-legal livelihood strategies: a Lesotho-based case study of cultivation of and trade in cannabis. J Polit Ecol. 2009;16:49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fields of Green for ALL. Cannabis: forced crop eradication in South Africa. Fields of Green for ALL: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Blickman T. Morocco and Cannabis–Reduction, Containment or Acceptance. Transnational Institute: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Blackman A, Samti F. Is marijuana decriminalization possible in the Middle East? Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/04/20/is-marijuana-decriminalization-possible-in-the-middle-east/ Accessed October 20, 2020.