Abstract

This study examines how adults with limited expressive language (with average sentences of five words or less) respond to open-ended questions. Participants (n = 49) completed a baseline measure and were then interviewed about a personal experience using exclusively open-ended questions, followed by open-ended and directive questions about a staged event. Their interviews were coded for mean length of utterance (MLU), number of different words and six dimensions of the Narrative Assessment Profile. Descriptively, the participants were able to give some event-related detail in their narratives, but there was wide variability in narrative quality. Correlational and regression analyses indicate that their MLU was stable across contexts. The findings suggest that adults with limited expressive language can provide informative responses to open-ended questions about their experiences, and that their expressive language is likely to show stability across introductory and substantive interview phases.

Keywords: practice narratives, limited expressive language, narrative quality, interview, complex communication, open-ended questions

People’s abilities to produce narratives of their personal experiences have myriad benefits, including improved ability to communicate with healthcare providers (Pennebaker, 2000), enhanced socio-emotional well-being (Bohanek & Fivush, 2010), identity construction (Hibbin, 2016), meaning-making, integration of experiences and relationship building (McAdams, 2008). Indeed, storytelling about personal experience is fundamental to many aspects of human life (McAdams, 2008). Being able to recount one’s experience is also important during activities that rely on information sharing, such as investigative interviewing and therapy.

The sharing of personal experience is supported by expressive language (Nippold, 2007). As such, adults with limited expressive language may be disadvantaged in these activities. A person with limited expressive language can be defined as any individual who uses sentences of approximately five words or less, with or without cognitive impairment (Hus Bal et al., 2016). Adults with limited expressive language are a heterogeneous group who demonstrate a range of complex conditions such as neuro-developmental disorders (e.g. autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy), traumatic brain injury and acquired language disorders like aphasia (Speech Pathology Australia, 2021). Their vocabulary is typically smaller and more basic than their verbally fluent peers, and expressive language difficulty is often – but not always – coupled with intellectual disability (Marrus & Hall, 2017).

The literature suggests that professionals who seek information from adults with limited expressive language can aid their verbal reports through effectively combining open-ended and specific questioning approaches (Agnew & Powell, 2004; Bearman et al., 2019; Cederborg et al., 2012). When eliciting information from this population, interviewers frequently rely heavily on specific questions. Such questions, however, heighten the risk of error due to interviewer bias and respondent suggestibility (Bull, 2010; Gudjonsson & Joyce, 2011). Yet, open-ended questions alone may yield incomplete detail when expressive language is limited (Agnew & Powell, 2004).

Open-ended questions are considered appropriate for children as young as preschoolers (3 to 4 years old) with typical expressive language ability (Gagnon & Cyr, 2017; Lamb et al., 2003; Magnusson et al., 2021; Sternberg et al., 2001). Open-ended questions are defined as any question that elicits an elaborate response and does not specify what information is required (Wilson & Powell, 2001). In contrast to open-ended questions, specific questions do not encourage elaborate responses and do indicate to the interviewee what information is being sought. We distinguish two main categories of specific questions: directive (i.e. wh- questions, such as who, where, when) and closed (yes-no and other option-posing questions). Open-ended questions are considered superior to all other types because they allow respondents to express themselves in their own words, they do not suggest what answers should be given or what information is important (Foddy, 1993), they may make respondents feel listened to (Brubacher et al., 2019) and they elicit more accurate responses about remembered events (e.g. Sutherland & Hayne, 2001).

Relatively few studies have devoted attention to the complex issue of conducting verbal interviews with interviewees with limited expressive language. Lloyd et al. (2006) investigated the broader challenge of including people with expressive language difficulties in qualitative interview research. They noted that the voices of this population are quite absent from the literature because most qualitative interview studies have only involved articulate individuals. Concerns include that the responses of participants with limited expressive language may not be completely accurate or credible, that researchers may have difficulty interpreting meaning from their narratives or might imbue the responses with their own biases and that such participants would provide limited answers when asked open-ended questions. These sentiments largely echo those from the field of investigative interviewing, where interviewers assume that interviewees (of any age) with limited verbal skills will require specific questions to share their experiences (Bull, 2010).

Yet, in settings where information gathering is important to determine what has happened, eliciting a narrative is crucial. In interviews with children, interviewers often give the young interviewees an opportunity to practice providing a narrative by responding to open-ended prompts about a neutral or fun event from the past (Lamb et al., 2018). There are several benefits to practice narratives. The activity can help to build rapport between interviewer and interviewee because it establishes a process of interaction wherein the interviewee knows that they will be listened to, and it helps the interviewer and the interviewee to become accustomed to each other’s communication style (Roberts et al., 2011). Practising responding to open-ended prompts may (by the nature of the exercise) improve narrative proficiency. For example, children have been found to provide more information in response to the initial prompt after raising the topic of concern if they have first participated in an open-ended rapport-building phase (Sternberg et al., 1997). The ability to respond to open-ended questions about personal experiences likely generalises across various event types, which would suggest that there may be a role for practice narratives in investigative interviews with adults with limited expressive language.

The current study

We examined the personal recounts of a recent fun event from a subset of adults with limited expressive language who had participated in a larger memory study about a staged event (Bearman et al., 2019). Before being questioned about the staged event, all participants were asked to talk about a recent fun experience in response to unscripted open-ended questions (i.e. engage in a practice narrative). In the current study, we analyse these practice narratives for their linguistic properties (i.e. mean number of words per utterance and number of different words used) and narrative quality. The latter was assessed using the Narrative Assessment Profile (NAP; Bliss et al.,1998), which was originally developed to evaluate a number of dimensions of the narrative skills of individuals with severe communication challenges and has previously been used with children with specific language impairment (Miranda et al., 1998). The NAP dimensions include topic identification, topic maintenance, event sequencing, referencing, explicitness and conjunctive cohesion. These dimensions are particularly relevant to eliciting reliable information about past events. Narrative quality is important in investigative interviews because it is associated with better comprehension among listeners (Newman & McGregor, 2006). Thus, mastery of these dimensions is associated with a better overall recount, which is crucial during investigative interviews.

The present study has two main aims: (1) to examine the quality of participants’ practice narratives in order to provide evidence that adults with limited expressive language can respond effectively to questions that encourage them to provide narrative information and (2) to investigate the extent to which the linguistic ability of adults with limited expressive language generalises across different events. We expected that there would be a strong positive correlation between the mean length of utterance (MLU) measured when participants were describing a personally relevant event and the MLU when recalling the laboratory staged event. We further predicted that participants’ ability to generate meaningful personal experiences (as demonstrated by the NAP dimensions and the number of different words used) would be strongly related to their productivity in responding to open-ended prompts about the staged event. The presence of these relationships would indicate that investigative interviewers can successfully use the practice narrative phase as a preliminary means of becoming familiar with the linguistic ability of an interviewee with limited expressive language, in addition to using it for rapport-building, engagement and providing practice in responding to open-ended questions.

Method

Participants

The participants were involved in a larger study to test the effect of various interviewing protocols on the ability of adults with limited expressive language to recount a set of staged activities (Bearman et al., 2019). They were recruited via the leadership of disability care homes, brain injury support services, speech pathology groups and disability-supported workplaces in one state of Australia. These professionals were asked to nominate individuals in their care who they perceived to have very limited expressive language.

Some of the participants from the larger study were excluded from the current investigation: all of the participants who were interviewed using visual aids alongside the questioning, as well as 5 participants who did not complete the narrative practice phase because they wanted to speak immediately about the staged laboratory event. The present subsample includes 49 adults with limited expressive language, aged 18 to 74 years (evenly distributed through the age range: M = 46.39 years, SD = 14.34, Mdn age = 47; 47% female). They demonstrated a range of disabilities, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, intellectual disability and autism.

All individuals participated with personal and guardian (where appropriate) consent. Participants were given an accessible consent form written by a speech pathologist that contained simple language and images and could be read to them if required. They were told that someone would ask them questions about the activity sessions in which they had participated. Participation was voluntary and participants were free to withdraw their consent at any time (none withdrew consent). At the end of the study, the interviewer thanked the participants and asked them if they had any questions. Participants and their carers or guardians were given follow-up contact information in case any questions arose (none did) and to obtain the results of the research.

Materials and procedure

Baseline assessments

All participants completed an initial session in which their verbal abilities were assessed in order to confirm that they demonstrated limited expressive language. They were asked to tell a story with three four-part narrative sequence picture cards (Black Sheep Press, 2012). Their responses were transcribed and analysed using Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT; Miller et al., 2017). Consistent with SALT coding conventions, utterances were defined as independent clauses (subject + verb) with their associated dependent clauses (e.g. because, while, when, etc.). In addition, incomplete clauses in response to a question were also considered an utterance. Their baseline MLU (MLU-baseline) was measured in number of words. A non-verbal IQ assessment was administered using Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., 1998). The test contains 3 sets of 12 items for a maximum score of 36.

The interview

Individual interviews were conducted with each participant approximately one week after the baseline assessment session by a single interviewer who has extensive experience in asking open-ended questions to a range of interviewees. The interviews comprised two phases: a practice narrative phase in which the interviewer sought information about a recent and pleasant personal experience followed by the substantive phase where she asked participants about a set of staged events (Bearman et al., 2019). Ground rules were not delivered. The practice narrative phase is the focus of the current study. It was initially included in the main study simply as a way to foster rapport between interviewer and interviewee; therefore, it was delivered to all participants. We were struck by the ability of the participants to meaningfully describe their personal experiences in response to open-ended questions, and this became the impetus for the current paper.

After briefly introducing herself, the interviewer commenced the practice narrative with the following prompt: ‘Thanks for talking with me today. First I’d like to get to know you better. Tell me something fun you’ve done recently’. To pursue the account, the interviewer used open-ended follow-up prompts such as: ‘Tell me what happened the last time you did [event]’; ‘What happened then?’; and ‘Tell me more about the part where [previously disclosed detail]’. The only other prompts used were minimal encouragers (e.g. ‘Mmm-hmm’, ‘Uh-huh’, etc.), i.e. backchannel utterances which indicated that the speaker should continue. The practice narrative was terminated when no new information was being elicited and/or participants indicated that they could remember no more.

The practice phase was immediately followed by a substantive phase where the interviewer questioned participants about one or more instances of a repeated staged event. The staged events comprised a set of scripted activities (e.g. listening to music, having a snack). Participants in the current subsample were interviewed either with open-ended prompts followed by directive prompts or in an intermixed fashion where open-ended and directive prompts were alternated.

Coding

All interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Participants’ practice narrative phases were entered into SALT (Miller et al., 2017) to automatically generate the following linguistic measures: number of utterances, MLU in the practice phase (MLU-practice), MLU in the substantive phase (MLU-interview) and number of different words used during practice (NDW) to measure semantic diversity. In addition, the practice narratives were coded to measure narrative quality using the NAP (Bliss et al., 1998). Participants’ responses in the interview were coded in each of the following six NAP dimensions: (i) topic identification, which refers to the extent to which the participant’s labels for the past personal event specified that event (e.g. ‘fun day’ versus ‘wedding’); (ii) topic maintenance, which relates to how well the participant’s narrative remained on topic or stuck to a central theme; (iii) event sequencing, which is associated with the narrative sustaining a chronological or logical order; (iv) explicitness, which relates to whether or not the individual’s narrative was informative or could be understood by a lay listener; (v) referencing, which relates to whether or not the narrative involved the identification of individuals, features and events before pronouns were used to refer to them and (vi) conjunctive cohesion, which describes whether or not the participant used words or phrases that linked utterances and events (e.g. ‘and then we did [event]’). Participants received a score out of 2 for each of the categories (where 0 = not evident, 1 = some evidence, 2 = mastered). Examples of two transcripts and final coding sheets are provided in Appendix A.

Reliability

The first author coded all transcripts. This author has extensive experience in coding question types, and regularly demonstrates reliability of coding for question types at Cohen’s κ ≥ .90 in related research. To assess the reliability of the coding for the NAP dimensions, 15 transcripts (20%) were coded by a second coder who was otherwise not associated with the research and blind to the study’s purpose. Cohen’s κ was used to calculate interrater reliability across all of the NAP dimensions, NDW, transcription of words and utterance segmentation (to generate MLU values). Reliability was found to be .85 or greater for all measures.

Results

Preliminary checks and data screening

First, we screened the data for statistical assumptions, missing values and outliers. One participant was unable to complete the Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., 1998) due to physical restrictions, so we replaced the missing value with the variable mean. Several variables were positively skewed by the presence of between two to five outliers above the mean (number of utterances per prompt in practice, NDW and MLU-interview). In all but two situations, however, outliers were less than 3 standard deviations (SDs) from the mean and there were no outliers on the baseline measures. One participant was an outlier >3 SDs on only one variable (number of utterances per prompt in practice). The other was an outlier >3 SDs on all three of the variables mentioned above but was not identified as an influential observation in the regression. Accordingly, we elected to retain all participants.

Next, we assessed whether or not there are any differences in the narrative variables across the two interview conditions. Even though the practice phase was conducted identically across the two conditions, we wanted to ensure that the groups are comparable. None of the comparisons across 9 measured continuous variables (see Table 1) were found to be significant at a corrected alpha of .005, ts ≤ 2.03, ps ≥ .048, Cohen’s ds ≤ .24, thus the interview condition is not considered further.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for performance measures (n = 49).

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices | 4.00 | 35.00 | 15.86 (8.88) |

| MLU-baseline | 1.06 | 7.06 | 3.46 (1.57) |

| MLU-practice | 1.00 | 7.50 | 3.57 (1.42) |

| NDW | 8.00 | 156.00 | 38.92 (32.22) |

| NAP total (max 12) | 0.00 | 11.00 | 5.25 (2.89) |

| Utterances in practice | 3.00 | 65.00 | 17.18 (11.95) |

| Prompts in practice | 4.00 | 35.00 | 14.96 (6.82) |

| Utterances per prompt | 0.32 | 5.91 | 1.37 (1.16) |

| MLU-interview | 1.27 | 7.35 | 3.00 (1.52) |

Note. MLU = mean length of utterance; NAP = Narrative Assessment Profile; NDW = number of different words used.

On average, the practice narrative phase lasted 3 min 10 sec (SD = 1 min 30 sec; range = 1 min 25 sec−6 min 30 sec). The length of the practice narrative is not correlated with any dependent variables, ps ≥ .053. The remainder of the interview averaged 10 min 50 sec (SD = 5 min 0 sec; range = 5 min 7 sec−31 min 36 sec).

Analytic plan

Our goals with this project are twofold: (1) to describe the overall narrative performance in a sample of adults with limited verbal ability who were interviewed about a personal experience using exclusively open-ended prompts and (2) to examine whether or not the linguistic and quality measures derived from the practice narrative (i.e. talking about a personal event) are associated with baseline measures of verbal and non-verbal ability, and whether or not they are predictive of MLU when talking about a staged laboratory event (i.e. the substantive phase). In the first section of the results we provide descriptive characteristics of performance. In the second section we present correlations and a regression analysis predicting average MLU during the substantive portion of the interview.

Describing participants’ performance

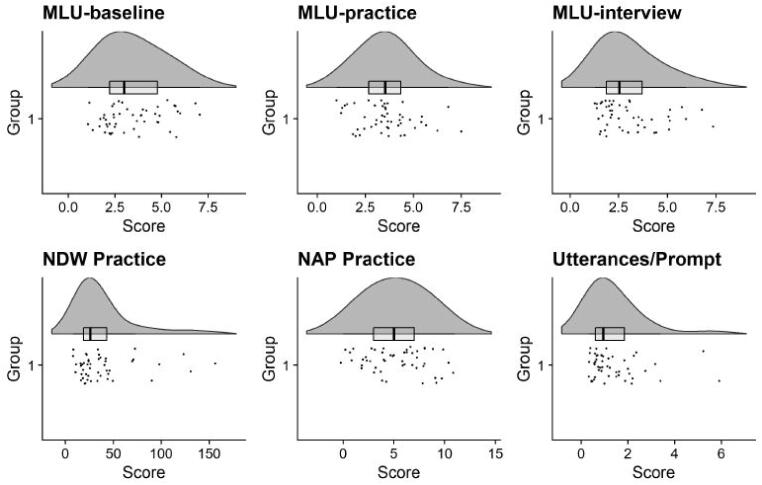

The descriptive statistics illustrate wide variability across most of the measured variables (for means and ranges, see Table 1 and Table 2). Although the MLU in all phases indicates that participants gave very brief responses (approximately 3 words per utterance), the average number of different words used in their practice interviews is nearly 40. This means that with repeated open-ended prompting, these adults with limited expressive language provided new information. The heterogeneity of participants’ scores for the continuous variable language measures (MLUs, NDW and NAP scores) can be seen in the rain cloud plots in Figure 1 (Allen et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for NAP dimensions (n = 49).

| NAP subscale | No evidence | Some evidence | Mastered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic identification | 7 | 2 | 40 |

| Topic maintenance | 9 | 20 | 20 |

| Event sequencing | 21 | 16 | 12 |

| Explicitness | 9 | 22 | 18 |

| Referencing | 15 | 30 | 4 |

| Conjunctive cohesion | 41 | 6 | 2 |

Note. For the NAP subscales, the number represents frequency of participants observed.

Figure 1.

Rain cloud plots of continuous narrative measures.

With regard to the NAP dimensions, participants demonstrated mastery on some elements but difficulties were also observed. Most were able to give a useful label for the topic being discussed. Being able to maintain that topic throughout the practice phase, being informative (explicitness) and using appropriate referencing to people, places and objects showed moderate levels of competence (i.e. a score of 1). Event sequencing and conjunctive cohesion were clearly the most difficult, reflected by the number of participants scoring 0 in these categories.

Relationships among narrative measures

Table 3 shows the correlations among the measures at the initial assessment (non-verbal IQ and MLU-baseline), the spoken language measures during the practice narrative (MLU-practice, NDW, total NAP and number of utterances per interviewer prompt) and the MLU for the substantive phase (MLU-interview).

Table 3.

Correlations among performance and narrative measures [95% confidence interval].

| Raven’s | MLU-baseline | MLU-practice | NDW practice | NAP practice | Utterances per prompt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLU-interview | .38** [.11, .60] | .82*** [.70, .90] | .72*** [.58, .82] | .42** [.16, .63] | .27 [−.01, .51] | .04 [−.24, .32] |

| Raven’s | – | .52*** [.28, .70] | .35* [.08, .58] | .37** [.10, .59] | .07 [−.22, .34] | .07 [−.22, .34] |

| MLU-baseline | – | .81*** [.69, .89] | .64*** [.44, .78] | .26 [.02, .47] | .27 [−.01, .51] | |

| MLU-practice | – | .72*** [.55, .83] | .32* [.04, .55] | .36** [.08, .58] | ||

| NDW practice | – | .18 [−.11, .44] | .73*** [.57, .84] | |||

| NAP practice | – | .01 [−.27, .29] |

Note. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. MLU = mean length of utterance; NAP = Narrative Assessment Profile; NDW = number of different words used.

The relationships among the individual NAP dimensions and the other language measures were assessed with Kendall’s coefficient of rank correlation τb. Given that there are six dimensions, we evaluated as significant only those correlations with a dependent variable that survived an alpha correction of .05/6 (p = .008). MLU-practice is correlated with explicitness, rτ (47) = .31, p = .006. Those participants with higher MLU scores for the practice narrative also rank higher on the explicitness dimension of the NAP. This was the only comparison to survive the alpha correction, but explicitness was found to be nearly significant (ps = .009) in two other comparisons, so we decided to include it in the regression model. Otherwise, individual NAP dimensions are not considered further.

As can be seen in Table 3, the MLUs at all three time points are strongly correlated with one another. This pattern suggests that the participants’ expressive language was stable regardless of whether they were describing a concrete visual stimulus (i.e. the picture cards), recalling a past personally-relevant event or recalling a past staged event. Non-verbal IQ is strongly correlated with MLU for the concrete stimulus and moderately correlated with MLU for the remembered events. This finding is reflective of the fact that limited verbal ability is frequently associated with other cognitive impairments (Marrus & Hall, 2017). NDW is strongly associated with MLU at all time points and non-verbal IQ. Like the MLU measures, however, it was not found to be associated with any of the NAP dimensions (ps ≥ .009; corrected alpha).

To assess the degree to which the narrative elements of the practice narrative and non-verbal IQ could predict the MLU during the substantive phase of the interview, we entered the variables that significantly correlate with MLU-interview, along with explicitness, as predictors in a multiple linear regression analysis (see Table 4). Given the very high correlations between MLU-baseline, MLU-practice and MLU-interview (rs > .80), to avoid issues of multicollinearity we omitted MLU-baseline from the model.1 The model is significant, F (4, 44) = 14.92, p < .001, with an R2 of .58. However, MLU-practice is the only significant predictor (p < .001). Holding all other variables constant, participants’ interview MLU increased by 0.78 words for each 1-word increase in their practice MLU.

Table 4.

Regression analysis predicting MLU-interview.

| B | SE B | β | p | 95% CI | Tolerance | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.32 | 0.47 | – | .50 | −1.26, 0.63 | – | – |

| MLU-practice | 0.84 | 0.16 | 0.78 | <.001 | 0.52, 1.15 | 0.45 | 2.24 |

| Raven’s | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.18 | .095 | −0.01, 0.07 | 0.85 | 1.17 |

| NDW practice | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.24 | .10 | −0.03, 0.00 | 0.47 | 2.13 |

| Explicitness | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.11 | .29 | −0.21, 0.69 | 0.83 | 1.20 |

Note. MLU = mean length of utterance; NDW = number of different words used.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that adults with limited expressive language were able to produce personal narratives in response to open-ended questions with at least some degree of detail and narrative quality. The MLU was found to be highly stable regardless of whether the participants were narrating in response to a visual stimulus (i.e. the baseline assessment), talking about a personally meaningful experience or reporting about a staged event. The only significant predictor of expressive language for the staged event is expressive language in the introductory phases (i.e. MLU-practice and MLU-baseline).

Professionals tasked with gathering information from adults with limited expressive language may find it helpful to engage these interviewees initially in open-ended recall on an unrelated topic (either using visual cards or eliciting a practice narrative). There are no significant associations between the narrative quality dimensions and the measures of expressive language except for explicitness. At corrected alpha levels, explicitness is significantly correlated with MLU-practice. This finding means that participants who used more words in their utterances about their personal events were more likely to produce narratives that a layperson would understand. Explicitness is also marginally correlated with NDW and MLU-interview (p = .009). Overall, the general lack of relationships with the NAP dimensions indicates that participants’ ability to produce narratively coherent accounts was not tied to the number of words per utterance. In other words, their brief responses did not necessarily lack narrative quality. Prior work with children has shown that narrative quality tends to be enhanced when interviewers use open-ended questions (Snow et al., 2009) and that narrative quality is associated with a comprehensible, logical account (Paul, 2001).

Non-verbal IQ, assessed with Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., 1998), was found to be associated with language productivity (i.e. MLU) in all interview phases but not at all with narrative quality (i.e. the NAP dimensions; ps ≥ .29). These findings suggest that expressive language difficulties, but not intellectual disability, may underlie the challenges in recounting personal narratives in this sample. This finding appears to be in contrast with prior studies, which have found that individuals with intellectual disabilities have difficulty producing detailed and complete narratives (Agnew & Powell, 2004; Brown et al., 2012). The contrasting results could be due to the fact that these studies have not measured both the intellectual and verbal functioning of their participants, and thus individuals with intellectual disabilities may have also had communication difficulties that were not documented.

The findings from the present research should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, we are unable to judge the accuracy of the practice narratives; however, past research has shown that open-ended questions are likely to produce accurate descriptions of past events from interviewees (Agnew & Powell, 2004; Lamb et al., 2018). Second, because participants chose their own events to describe during narrative practice, there is diversity in the complexity of the events they talked about. Nevertheless, this is likely to be random across participants. Furthermore, the baseline assessment was standardised and shows similar heterogeneity of performance. Third, the participants were relatively unfamiliar with the interviewer, and some inhibition to share personal experiences may have impacted the results. These results, therefore, may not demonstrate the optimal performance of the present sample but they should generalise to situations where professionals (e.g. doctors, nurses, police officers, etc.) would be unfamiliar with the interviewee when trying to elicit accurate information about events during investigations. Relatedly, an important caveat to consider is that the participants were cooperative witnesses being interviewed about pleasant events; therefore, the strength of the relationship between their productivity in the introductory interview phase and the substantive phase (i.e. the main interview) may be overestimated. Reluctance associated with negative topics can reduce people’s willingness to talk in the substantive phase. Yet, some evidence suggests that reluctance can already be identified prior to broaching substantive issues (Hershkowitz et al., 2006), in which case the relationships in productivity across the phases should hold.

Despite its limitations, the current study is unique in that it focuses on adults with limited expressive language and explores using only high-quality, open-ended questions and prompts during a practice phase with this cohort. When implemented correctly, practice in responding to open-ended prompts may improve the amount of information reported in subsequent interview phases (Sternberg et al., 1997; Whiting & Price, 2017). This question cannot be answered with the present data owing to the lack of a no-practice control group, but it is worthy of future research. Professionals such as speech pathologists and carers working with individuals who have limited expressive language should incorporate open-ended questions into everyday interactions. By utilizing open-ended questions when interviewing adults with limited expressive language, we may provide them with greater access to the justice system and a greater quality of life. Importantly, interviewers may be able to use MLU during early interview phases as a potential indicator of expected performance when discussing the topic of concern. Although open-ended questions should be the default, some experts have suggested that interviewers might aid interviewees with communication challenges even further by scaffolding their narrative accounts with some directive questions (e.g. ‘Where did [the event] happen?’) and pairing these with open-ended ones (Bearman et al., 2019; Hershkowitz et al., 2012; Lloyd et al., 2006)

Conclusions

The present research supports the notion that the ability of adults with very limited expressive language skills to respond to open-ended questions generalises across event types. The findings also add weight to the argument that people with limited expressive language are able to provide narrative accounts when questioned effectively. Indeed, experts have intimated that one reason we know little about people’s subjective experiences of various conditions that inhibit their communication is due to our inability to question them in ways that permit them to express themselves (Lloyd et al., 2006). This sentiment echoes those of developmental psychologists who suggest that what children can tell us about their experiences is largely attributable to the quality of our questions (Brown & Lamb, 2015). Taken together with other research, the current study supports the recommendation that engaging adults with limited expressive language in a brief open-ended interview about an unrelated topic prior to discussing substantive issues may be a helpful way to gauge their communication ability, in addition to building rapport and preparing them for the main interview.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the individuals who took part in this project.

Appendix A.

Two examples of transcripts and narrative assessment profile coding

Example 1

(Examiner prompts in capitals)

TELL ME SOMETHING FUN YOU’VE DONE

(Um) see the Christmas lights.

WHAT DID YOU DO THERE?

I looked around

MHM

WHAT ELSE HAPPENED?

I looked around with [friend name]

YEP

(Um) went a walk with the dog

YEP

(Um) I don’t know what else

THAT’S OKAY. TELL ME MORE ABOUT THE PART WHERE YOU WENT FOR A WALK WITH THE DOG

To the park

MHM

And look around

Example 1 Coding

| Narrative assessment profile element | 0 – absent/no evidence | 1 – some evidence | 2 – yes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic ID | 2 – Christmas lights | ||

| Topic maintenance (are utterances on topic?) | 1 – not clear if the dog walk was connected to the Christmas lights | ||

| Event sequencing (are events in chronological order?) | 1 – some sequencing, to the park | ||

| Explicitness (can we understand the narrative? Is it elaborate? Is there description, action and evaluation?) | 1 – some action, walk dog to the park | ||

| Referencing (are there individuals, features and events?) | 1 – (the dog) [friend name] | ||

| Conjunctive cohesion (is it linked? Does the individual use conjunctions such as ‘and then’?) | 0 – No evidence of appropriate use of conjunctions |

Example 2

SO NOW I WANT YOU TO TELL ME SOMETHING FUN THAT YOU’VE DONE RECENTLY

Okay, well on a Monday night

YEP

I go to lawn bowls

YEP

Thursday nights I go to basketball to play [Team A]

MHM

And Tuesday nights I go to [Place A] park

MHM

On Saturdays I go see [Team B] play at the [Place B] oval

OKAY I WANT YOU TO TELL ME WHAT IS THE FIRST THING YOU DO WHEN YOU GO TO LAWN BOWLS?

Go there and I play

YEP

Straightaway

YEP

We are told to start

YEP

I play bowls and then I play basketball

WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN YOU PLAY BOWLS?

I put the bowl down near the jack

YEP

Get as close as I can

GOOD AND WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN YOU PLAY BASKETBALL?

Yep I play basketball I shoot goals I run hard

MHM

When we win I am happy

THAT’S GOOD

Then after that I come home, have tea, I come home and have tea at home

MHM

And then I, then on Saturday night this week I will be going to see [Team B] and [Team C] play

MHM

And I hope the [Team B] win because now we are on top

IT’S STILL EARLY DAYS YET

And I do football tips here at work

MHM

[Friend name] and I go out for tea, out for tea sometimes

MHM

And I’ve been with [friend name] for three years

YEP

Her and I go out together, we live together, we do things together, we clean the unit together, enjoy time together, she goes home and stays for Easter, and might do something for Easter

MHM

Sunday what we do, then enjoy the weekend and go to the football watch the [Team B] play

YEP

Watch the other games on TV

MHM

And go to bed after that and sleep

Example 2 coding

| Narrative assessment profile element | 0 – absent | 1 – some evidence | 2 – yes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic ID | 2 – lawn bowls | ||

| Topic maintenance (are utterances on topic?) | 1 – does talk about each category for a bit before changing | ||

| Event sequencing (are events in chronological order?) | 1 – some sequencing for bowls, we are told to start, I put the bowl down near the jack, get as close as I can | ||

| Explicitness (can we understand the narrative? Is it elaborate? Is there description, action and evaluation?) | 2 – explains multiple activities in quite good detail | ||

| Referencing (are there individuals, features and events?) | 2 – [friend] and I go out together, we live together, we’ve been together for three years | ||

| Conjunctive cohesion (is it linked? Does the individual use conjunctions such as ‘and then’?) | 1 – some conjunctions, after that I come home and have tea (doesn’t always use though) |

Footnotes

If MLU-baseline is substituted for MLU-practice in the stepwise regression, the results are the same: only MLU-baseline is a significant predictor (p < .001; all other ps ≥ .10). The model is significant, F (4, 44) = 24.99, p < .001, with an R2 of .69. Holding all other variables constant, participants’ interview MLU increased by 0.92 words for each 1-word increase in their baseline MLU. Although this model is statistically stronger than the MLU-practice model, the practical difference is very small – and given that our focus is on performance for talking about a remembered event (i.e., practice narratives), we elected to present the model with MLU-practice. Broadly, however, the results suggest remarkable consistency in MLU across descriptions of three unique events.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Madeleine Bearman has declared no conflicts of interest.

Marleen Westerveld has declared a perceived conflict of interest in that she has a financial relationship with SALT Software LLC (used to identify utterances in the current study); however, SALT Software LLC was not involved in the conceptualisation of the study or the analyses of the results and did not view the manuscript prior to submission.

Sonja P Brubacher has declared no conflicts of interest.

Martine Powell has declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

Author note

This research was conducted as part of the PhD dissertation of Madeleine Bearman.

References

- Agnew, S. E., & Powell, M. B. (2004). The effect of intellectual disability on children’s recall of an event across different question types. Law and Human Behavior, 28(3), 273–294. 10.1023/B:LAHU.0000029139.38127.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M., Poggiali, D., Whitaker, K., Marshall, T. R., & Kievit, R. A. (2019). Raincloud plots: A multi-platform tool for robust data visualization. Wellcome Open Research, 4, 63. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15191.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman, M., Brubacher, S. P., Timms, L., & Powell, M. (2019). Trial of three investigative interview techniques with minimally verbal adults reporting about occurrences of a staged repeated event. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 25(4), 239–252. 10.1037/law0000206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black Sheep Press (2012). Four-part sequences (3rd ed., WIP7). © Helen Rippon. Black Sheep Press. www.blacksheeppress.com [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, L. S., McCabe, A., & Miranda, A. E. (1998). Narrative assessment profile: Discourse analysis for school-age children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 31(4), 347–363. 10.1016/S0021-9924(98)00009-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek, J. G., & Fivush, R. (2010). Personal narratives, well-being, and gender in adolescence. Cognitive Development, 25(4), 368–379. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. A., & Lamb, M. E. (2015). Can children be useful witnesses? It depends how they are questioned. Child Development Perspectives, 9(4), 250–255. 10.1111/cdep.12142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. A., Lewis, C. N., Lamb, M. E., & Stephens, E. (2012). The influences of delay and severity of intellectual disability on event memory in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 829–841. 10.1037/a00299388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubacher, S. P., Timms, L., Powell, M., & Bearman, M. (2019). ‘She wanted to know the full story’: Children’s perceptions of open versus closed questions. Child Maltreatment, 24(2), 222–231. 10.1177/1077559518821730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull, R. (2010). The investigative interviewing of children and other vulnerable witnesses: Psychological research and working/professional practice. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 15(1), 5–23. 10.1348/014466509X440160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cederborg, A.-C., Hultman, E., & La Rooy, D. (2012). The quality of details when children and youths with intellectual disabilities are interviewed about their abuse experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 14(2), 113–125. 10.1080/15017419.2010.541615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foddy, W. (1993). Constructing questions for interviews and questionnaires: Theory and practice in social research. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, K., & Cyr, M. (2017). Sexual abuse and preschoolers: Forensic details in regard of question types. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 109–118. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudjonsson, G., & Joyce, T. (2011). Interviewing adults with intellectual disabilities. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 5(2), 16–21. 10.5042/amhid.2011.0108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkowitz, I., Lamb, M. E., Orbach, Y., Katz, C., & Horowitz, D. (2012). The development of communicative and narrative skills among preschoolers: Lessons from forensic interviews about child abuse. Child Development, 83(2), 611–622. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkowitz, I., Orbach, Y., Lamb, M. E., Sternberg, K. J., & Horowitz, D. (2006). Dynamics of forensic interviews with suspected abuse victims who do not disclose abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(7), 753–769. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbin, R. (2016). The psychosocial benefits of oral storytelling in school: Developing identity and empathy through narrative. Pastoral Care in Education, 34(4), 218–231. 10.1080/02643944.2016.1225315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hus Bal, V., Katz, T., Bishop, S. L., & Krasileva, K. (2016). Understanding definitions of minimally verbal across instruments: Evidence for subgroups within minimally verbal children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(12), 1424–1433. 10.1111/jcpp.12609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, M. E., Brown, D. A., Hershkowitz, I., Orbach, I., & Esplin, P. W. (2018). Tell me what happened: Questioning children about abuse (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, M. E., Sternberg, K. J., Orbach, Y., Esplin, P. W., Stewart, H., & Mitchell, S. (2003). Age differences in young children’s responses to open-ended invitations in the course of forensic interviews. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(5), 926–934. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, V., Gatherer, A., & Kalsy, S. (2006). Conducting qualitative interview research with people with expressive language difficulties. Qualitative Health Research, 16(10), 1386–1404. 10.1177/1049732306293846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, M., Joleby, M., Ernberg, E., Akehurst, L., Korkman, J., & Landström, S. (2021). Preschoolers’ true and false reports: Comparing the effects of the sequential interview and NICHD protocol. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 26(1), 83–102. 10.1111/lcrp.12185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marrus, N., & Hall, L. (2017). Intellectual disability and language disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26(3), 539–554. 10.1016/j.chc.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D. P. (2008). Personal narratives and the life story. In John O. P., Robins R. W., & Pervin L. A. (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 242–262). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J., Gillon, G., & Westerveld, M. (2017). Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) (New Zealand/Australia Student Version 18) [Computer software]. Salt Software LLC.

- Miranda, A. E., McCabe, A., & Bliss, L. S. (1998). Jumping around and leaving things out: A profile of the narrative abilities of children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 19(4), 647–667. 10.1017/S0142716400010407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, R. M., & McGregor, K. K. (2006). Teachers and laypersons discern quality differences between narratives produced by children with or without SLI. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49(5), 1022–1036. 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nippold, M. A. (2007). Later language development: School-age children, adolescents, and young adults (3rd ed.). Pro-ed. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, R. (2001). Language disorders from infancy through adolescence. Assessment and intervention (2nd ed.). Miss Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J. W. (2000). Telling stories: The health benefits of narrative. Literature and Medicine, 19(1), 3–18. 10.1353/lm.2000.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J., Raven, C., & Court, J. H. (1998). Manual for Raven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K. P., Brubacher, S. P., Powell, M. B., & Price, H. L. (2011). Practice narratives. In Lamb M.E., La Rooy D., Malloy L., & Katz C. (Eds.), Children’s testimony: A handbook of psychological research and forensic practice (2nd ed., pp. 129–146). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, P. C., Powell, M. B., & Murfett, R. (2009). Getting the story from child witnesses: Applying a story grammar framework. Psychology, Crime and Law, 15(6), 555–568. 10.1080/10683160802409347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speech Pathology Australia . (2021). Fact sheets: Communication impairment in Australia. https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/Resources_for_the_Public/Fact_Sheets/SPAweb/Resources_for_the_Public/Fact_Sheets/Fact_Sheets.aspx

- Sternberg, K. J., Lamb, M. E., Hershkowitz, I., Yudilevitch, L., Orbach, Y., Esplin, P. W., & Hovav, M. (1997). Effects of introductory style on children’s abilities to describe experiences of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(11), 1133–1146. 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00071-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, K. J., Lamb, M. E., Orbach, Y., Esplin, P. W., & Mitchell, S. (2001). Use of a structured investigative protocol enhances young children’s responses to free-recall prompts in the course of forensic interviews. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 997–1005. 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, R., & Hayne, H. (2001). The effect of postevent information on adults’ eyewitness reports. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15(3), 249–263. 10.1002/acp.700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, B. F., & Price, H. L. (2017). Practice narratives enhance children’s memory reports. Psychology, Crime & Law, 23(8), 730–747. 10.1080/1068316X.2017.132403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C., & Powell, M. B. (2001). A guide to interviewing children. Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]