ABSTRACT

Background: Numerous evidence-based trauma therapies for children and adolescents have been developed over several decades to minimize the negative outcomes of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, PTSD remains a complex construct and is associated with pervasive problems and high comorbidity. To gain more insight, much could be learnt from the similarities in trauma therapies.

Objective: The purpose of this study is to derive common elements from evidence-based trauma therapies for children and adolescents.

Method: Therapies were selected from a literature search. Five evidence-based trauma therapies were included in this study. A common element list was created through an existing and modified Delphi method, with a diverse group of Dutch trauma therapists. An element was deemed common when it appeared in three or more of the therapies. The final list was presented to international experts on the included trauma therapies.

Results: A substantial commonality of techniques and mechanisms was found across the five evidence-based trauma therapies for children and adolescents, showing a strong overlap between therapies.

Conclusion: The identified elements create a basis for research and clinical practice, with regard to targeted trauma therapies tailored to each individual child and his or her support system. This promotes therapy modules that are more flexible and accessible for both therapists and clients, in every environment, from specialized psychiatric units to sites with meagre resources. With current integrated knowledge, we can enhance the effectiveness of child psychiatry and refine trauma therapies.

HIGHLIGHTS

Using a modified Delphi method, a substantial commonality of techniques and mechanisms is found in evidence-based trauma therapies for children and adolescents.

Understanding the techniques and mechanisms of trauma therapy could be of help in refining upcoming therapies, and creates a basis for future research.

Commonalities promote therapy modules that are more flexible and accessible for both therapists and clients, in environments ranging from specialized psychiatric units to sites with meagre resources.

KEYWORDS: PTSD, youth, common elements, trauma therapy

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Abstract

Antecedentes: Una gran cantidad de evidencia relativa a terapias basadas en la evidencia para el trauma en niños y adolescentes se ha desarrollado en las últimas décadas, con el fin de minimizar los resultados negativos del TEPT. Sin embargo, el TEPT sigue siendo un constructo complejo y asociado con problemas generalizados, y una alta comorbilidad. Para obtener más información, se podría aprender mucho de las similitudes entre las terapias para el trauma. Por lo tanto, el propósito de este artículo es derivar elementos comunes de las terapias basadas en evidencia para el trauma en niños y adolescentes.

Método: Las terapias fueron seleccionadas a partir de una búsqueda bibliográfica. En este estudio se incluyeron cinco terapias de trauma basadas en la evidencia. Se creó una lista de elementos comunes a través de un método Delphi existente y modificado, con un grupo diverso de terapeutas de trauma holandeses. Un elemento se consideró como común cuando apareció en tres o más de las terapias. La lista final se presentó a expertos internacionales de las terapias de trauma incluidas.

Resultados y conclusión: Se encontró una coincidencia sustancial de técnicas y mecanismos en las cinco terapias de trauma basadas en la evidencia para niños y adolescentes, lo que muestra una fuerte superposición entre las terapias. Los elementos identificados crean una base para la investigación y la práctica clínica con respecto a las terapias de trauma específicas adaptadas a cada niño individual y su sistema de apoyo. Esto promueve módulos de terapia que son más flexibles y accesibles tanto para terapeutas como para clientes en cualquier entorno, desde unidades psiquiátricas especializadas hasta sitios con escasos recursos. Con el conocimiento integrado actual podemos mejorar la eficacia de la psiquiatría infantil y refinar las terapias de trauma.

PALABRAS CLAVE: TEPT, juventud, elementos en común, terapia de trauma

Abstract

背景:在过去的几十年中,针对儿童和青少年开发了大量循证创伤疗法,以尽量减少 PTSD 的负面结果。然而,PTSD 仍然是一个复杂结构,并且与普遍存在的问题和高共病有关。为了获得更多的洞察力,可以从创伤治疗的相似性中学到很多东西。因此,本文旨在从针对儿童和青少年的循证创伤治疗中得出共同要素。

方法:从文献检索中选择治疗方法。本研究纳入了五种循证创伤疗法。一个共同的元素列表是通过现有和修改版 Delphi 方法创建的,其中有一组不同的荷兰创伤治疗师。当一个元素出现在三种或更多的疗法中时,它就被认定为常见的。最终名单已提交给包括创伤治疗的国际专家。

结果和结论:在针对儿童和青少年的五种循证创伤疗法中发现了大量技术和机制的共性,表明疗法之间存在很强的重叠。确定的要素为研究和临床实践奠定了基础,涉及针对每个儿童及其支持系统量身定制的针对性创伤治疗。它为治疗师和客户提供更灵活、更易于使用的治疗模块——在各种环境中,从专业的精神病学单位到资源匮乏的场所。凭借当前的综合知识,我们可以提高儿童精神病学的有效性并改进创伤治疗。

关键词: PTSD, 青年, 共同元素, 创伤治疗

1. Introduction

There is an imperative need to improve the effectiveness of treatment for mental health disorders in children and adolescents. Timely and effective therapies can reduce not only the immediate burden of the disorders, but also their future impact. The commission on psychological treatments argued in 2018 that the time is ripe for innovative research on evidence-based treatments using existing data (Kessler et al., 2017). One mental health condition in youth that can have lifelong consequences is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Trauma-focused psychotherapies, such as trauma-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy (TF-CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), have demonstrated their effectiveness, both in clinical practice and in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Lewis et al., 2019). The next logical step is to unravel the most potent elements in such therapies; that is, those that induce change. Increased understanding of such techniques and mechanisms in therapies should enable more targeted, precise, and refined therapeutic strategies to be developed (Kessler et al., 2017). A common elements study is a designated method for finding such crucial mechanisms. If we can distinguish elements that are commonly applied in evidence-based therapies, we can argue that these play an important role. Defining common therapeutic elements can aid further exploration and the creation of more individually targeted therapies for young patients (Alisic et al., 2014).

A staggering number of children are exposed to traumatic or adverse events in their childhood. Prevalence rates for traumatic events range from 30% in children under 18 years up to 70% in a lifetime, depending on the type of adverse event recorded and the income level of a country. Usually, low-income countries show higher prevalences of traumatic experiences (Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, 2007; Green et al., 2010). Distress from traumatic events has a detrimental influence on children’s daily lives and development, and can lead to PTSD (Rojas et al., 2017). PTSD is known to have a high comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, such as depression in over 50% of the children diagnosed with PTSD, severe eating disorders, and high-risk behaviour (especially self-harm and suicidality) (Bastien, Jongsma, Kabadayi, & Billings, 2020; Copeland et al., 2007; Holmes et al., 2018; Rijkers, Schoorl, van Hoeken, & Pollet, 2019). Early and effective treatment of PTSD is therefore needed to minimize such negative outcomes in individual children, the probability of intergenerational transmission, and the negative effects on society.

1.1. Development of trauma therapy

Since 1980, PTSD in children has been recognized and described in the literature (Terr, 1983). Protocolled trauma therapies targeting PTSD symptoms in youth developed rapidly in the ensuing decades. Cognitive–behavioural therapies (CBTs) were applied to reduce trauma symptoms such as anxiety, flashbacks, and avoidance of trauma triggers (Terr, 1983). In the late 1990s, CBT for PTSD in youth began focusing increasingly on the trauma itself, originally in a cohort of sexually abused children (Beck, 1979). Gradually, the focus shifted to a broader range of types of traumatic event and to the engagement of non-offending caregivers in the therapy (Cohen & Mannarino, 1996). During this period, exposure therapy, the initial focus of which had been on anxiety disorders, was extended to PTSD (Rothbaum & Schwartz, 2002). Adaptations to exposure therapy for adolescents were made 10 years later (Foa, 2011). Narrative therapies, influenced by the framework of CBT, arose in the early 2000s (Chrestman & Gilboa-Schechtman, 2008), employing writing, or the trauma narrative, as an exposure tool; adaptations for children and adolescents were implemented several years later (Elbert & Neuner, 2005; Van der Oord, Lucassen, Van Emmerik, & Emmelkamp, 2010). All of these different therapies relied on a model of habituation and cognitive reframing, in the belief that any form of exposure, while simultaneously challenging dysfunctional cognitions, will induce a natural extinction of anxiety in the absence of a feared response (Groves & Thompson, 1970).

During the same time frame in which the model of habituation and cognitive reframing was developed for PTSD, another model arose to explain the processing of traumatic events: the adaptive information processing (AIP) model. In this approach, traumatic memories, with their affective distress, are combined simultaneously with unrelated external stimuli, for example triggering rapid eye movements, that diminish affective arousal. This theory and therapy were first described in the late 1980s and were adapted for children in the 2000s (Shapiro, 1989; Tinker & Wilson, 1999).

In the past two decades, an impressive number of protocolled trauma therapies have emerged from these theoretical orientations. These therapies were created and refined over the years, and many are now well established. Multiple reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that trauma-focused psychotherapy is effective for lowering traumatic stress symptoms, and it is therefore the treatment of choice for children and adolescents whose development is affected by PTSD (Bastien et al., 2020; Morina, Koerssen, & Pollet, 2016).

1.2. Current challenges in trauma therapy

PTSD remains a complex construct nonetheless, and is associated with pervasive problems and high comorbidity (Copeland et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2019; Rijkers et al., 2019). We face challenges of misdiagnosis or inaccurate therapies when manifested problems are not recognized as traumatic symptoms (Morina et al., 2016). Psychotherapy dropout and early termination are also common (Burns et al., 2004; Imel, Laska, Jakupcak, & Simpson, 2013), with rates up to 25–30% in child and adolescent trauma therapy (Diehle, Opmeer, Boer, Mannarion, & Lindauer, 2015; Miller, Southam-Gerow, & Allin, 2008). Debates are ongoing about which trauma therapy is most effective for this complex, heterogeneous group of young people, and many studies highlight differences between various therapies (Bastien et al., 2020). The focus on independent therapies nurtures isolated research on specific manuals, which can impede the creation of a joint effort to match PTSD interventions to each individual. Much could be learnt from research that explores the similarities in trauma therapies. Identifying these similarities could provide more clarity on the common therapeutic techniques and principal mechanisms through which the therapies work (Ormhaug & Jensen, 2018; Garland, Hawley, Brookman-Frazee, & Hurlburt, 2008). This information could be beneficial for professionals who do not have the capacity or resources available to gain expertise on a protocol or manual (Garland et al., 2008). If common elements could be determined, this would provide a more evidence-based approach to integrating different elements in clinical practice. It would establish a basis for all trauma interventions, which could then be adapted to fit the specific needs, learning style, and motivation of each child or adolescent who is experiencing PTSD (Ormhaug & Jensen, 2018; Garland et al., 2008).

The research for this paper arose from the distillation and matching model created by Chorpita and colleagues (Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005). This model makes use of existing therapies, from which elements are distilled and used to match to the individual client. This model improves our understanding of similarities between psychological therapies, and has been used in common element studies on behavioural problems in children (Garland et al., 2008) and on systematic treatment for disruptive behaviour in adolescents (van der Pol et al., 2019). These two studies added a modified Delphi method to elicit expert opinions on the evidence-based treatment elements. This framework (establishing evidence-based therapies, reviewing therapy materials through an adaptive Delphi method, and surveying experts) has demonstrated the feasibility of establishing commonalities in psychotherapy. Using this framework to establish commonalities in trauma therapy could be essential in an effort to derive and refine therapeutic strategies, actuate therapeutic mechanisms, remove irrelevant strategies, and develop novel approaches that are more direct, precise, and individually targeting (Kazdin, 2007). The purpose of this paper is therefore to derive common elements from evidence-based trauma therapies for children and adolescents.

2. Method

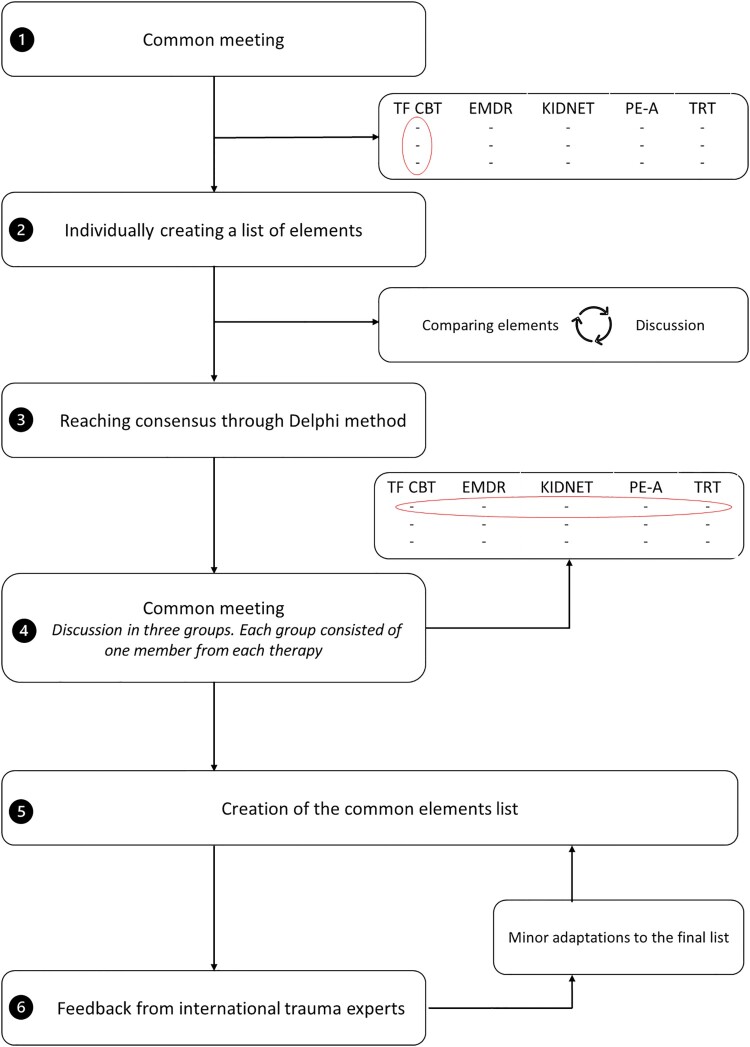

To identify such common elements in youth trauma therapies, we used the adaptation of the Delphi technique developed by Garland and colleagues (Garland et al., 2008). The method is a well-established iterative group judgement technique applied in research to identify quality-of-care indicators. Outcomes of a systematic search and opinions of therapists and experts are combined and used to reach consensus. Our current research employed this method in the following steps: (1) a literature search for evidence-based trauma therapies; (2) analysis of treatment protocols of the identified therapies by each individual trauma therapist; (3) Delphi meetings with trauma therapists to achieve consensus on core elements and establish common elements; and (4) interviews with international trauma therapy experts and the authors or developers of each treatment protocol.

2.1. Literature search

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science Conference Proceedings (WSCP) were searched from inception (see Appendix 1 in the supplementary material for full details). Criteria for inclusion were (1) the therapy aimed to treat PTSD and used PTSD symptoms as an outcome measure; (2) the treated population was between 7 and 18 years of age; (3) the therapy was studied in an RCT research design; and (4) the study was written in English.

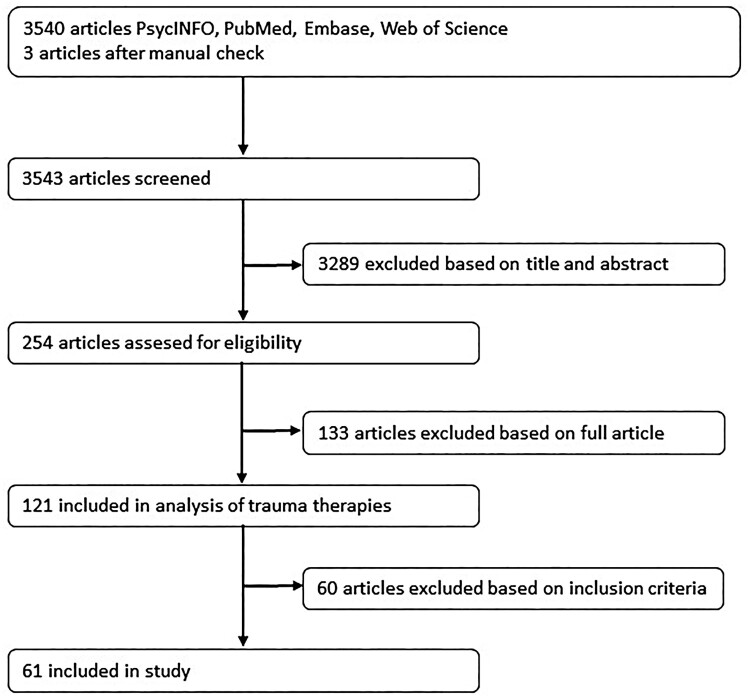

The literature search performed in April 2020 yielded 3540 articles, and three more were identified in a manual database check. Two of these three articles were published in a journal that did not appear in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, or WSCP. The third article was poorly administrated and for this reason it was not found in our first search. Relevant articles were first identified through title screening by LHK, followed by a consensus-based abstract screening of eligible RCT articles, carried out by LHK and RJLL. This resulted in 121 potentially eligible articles (Figure 1), from which we selected the therapies that met the ‘probably efficacious’ level of support, according to the American Psychological Association. Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures Division of Clinical Psychology (1995). This level of support requires at least two RCTs with waiting-list controls, a single RCT with an active control, or a small series of single case design experiments using a comparison of active treatments. In consensus. the authors decided to sharpen the criteria up front towards at least three published RCTs, one of which was not conducted by the authors or developers of the therapy. The final selection was made by LHK and RJLL and checked by TP, and yielded 61 relevant articles. These 61 articles described research on five evidence-based trauma therapies: (1) trauma-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy (TF-CBT), (2) eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), (3) narrative exposure therapy for children (KIDNET), (4) prolonged exposure therapy for adolescents (PE-A), and (5) teaching recovery techniques (TRT). The vast majority of the studies were conducted in a population with high accessibility to modern resources and possessing a low poverty rate (i.e. developed countries) and in this study 16 studies focused on refugee children or trauma therapy in developing countries or areas with lower levels of resources (see Appendix 2 in the supplementary material).

Figure 1.

Review of the literature.

2.2. Participants in the Delphi trauma therapist group

Therapists with expertise in youth trauma therapy were recruited from different trauma expertise and mental health institutions across the Netherlands. A short summary of the method and the estimated time investment was sent out in an e-mail to 20 therapists. They were asked whether they knew other therapists that we may have missed. This resulted in 22 therapists and three therapists with personal experience in therapy for trauma who were approached. They were asked to participate voluntarily. For personal or logistic reasons, eight therapists could not join. The final therapist group consisted of 17 therapists specializing in treating children and adolescents from 10 different mental health institutions, including two with personal trauma therapy experience. Among them were two psychiatrists, five specialized clinical psychologists or psychotherapists (Dutch terms KP-psychologen and PT-psychologen), nine health psychologists (GZ-psychologen), and one non-specialized psychologist (basispsycholoog). In this group, nine therapists held PhDs and two were PhD candidates. All therapists had training in one or more of the evidence-based trauma therapies for children or adolescents within the Dutch education system. Therapists were assigned randomly to a therapy, which resulted in nine therapists being assigned to a therapy in which they were trained. The majority of each Delphi group was not trained in the specific therapy, except for the EMDR group, which comprised therapists who were all trained in EMDR and one (or more) of the other therapies. One therapist was not trained in any trauma therapy, and supervised each Delphi group regarding questions on the procedure and study method.

2.3. Procedure

After establishing the five evidence-based therapies to be analysed in this study, we launched the Delphi group in a joint meeting with the therapists (step 1). In this first meeting, we elucidated the rationale, goal, and planning of the research. An explanation of the modified Delphi method was given, along with examples from previous studies using this framework (Garland et al., 2008; van der Pol et al., 2019). Each therapist was assigned to one of the five trauma therapies, resulting in three or four therapists per therapy. In the months that followed, each therapist individually studied their assigned protocol or manual and created a preliminary list of therapy elements (step 2). To qualify as a valid therapy element, the element was to be described in the therapy material, and explicit details were to be included about how to use that specific element (such as duration, frequency, and manner). Therapy elements are describable at different levels (very specific, intermediate, or very broad). In this study, we chose to use a broad-to-intermediate conceptualization of elements to ascertain the common ground between the manuals. Subsequently, elements were categorized as therapy parameters (characteristic components that define the structure of a therapy), therapy techniques (specific interventions used in the therapy to address feelings, behaviours, and cognitions), or therapy mechanisms (the process through which the therapy unfolds and produces change). The list of individual elements was then presented to all other group members, and disagreements were discussed (step 3). Each group reached consensus on the core elements of its assigned therapy after a few sessions (averaging two sessions per group). In the final joint meeting, we created three groups, consisting of one member from each therapy, in which we tried to reach consensus on core elements (step 4).

Following the review and consensus process for the five trauma therapies, all of the selected therapy elements were gathered together and compared with one another. In this process, a therapy element was considered to be common if it had been identified in at least three of the five therapies (step 5). We chose to focus on elements that were described for the young clients, since not every manual explicitly described caregiver elements. If the common element was also described for parents or caregivers, that was noted in the results summary. Finally, the common elements list, categorized into parameters, techniques, and mechanisms, was presented for feedback to the international trauma experts linked to the various trauma therapies (step 6). These experts were the 11 international authors or developers of each therapy. From all five therapies, at least one expert provided responses or feedback, after which we made minor changes to the final results list.

These six steps are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the research procedure. TF-CBT = trauma-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy; EMDR = eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; KIDNET = narrative exposure therapy for children; PE-A = prolonged exposure therapy for adolescents; TRT = teaching recovery techniques.

3. Results

The therapists identified several common elements across the various trauma therapy protocols (see Appendix 3). Table 1 summarizes the parameters common to all five therapies. Tables 2 and 3 list the common techniques and mechanisms, displaying the element, definitions, and number of therapies in which the technique or mechanism was identified. After consulting the experts, we made some minor adaptations and changes in language. One significant change was made when we found that the mechanism ‘therapeutic relationship’ was explicitly mentioned in four manuals. In the therapist team and the expert feedback, it became clear that the therapeutic relationship was likewise an important element in the fifth therapy and was to be described in an upcoming version of the protocol. We therefore changed the number to five therapies.

Table 1.

Parameters.

| Description or range | |

|---|---|

| Referral assessment | Diagnosed PTSD or PTS symptoms |

| Age | 0–18 years |

| Frequency | Once weekly |

| Sessions | 1–25 sessions |

| Session length | 45–90 minutes |

| Therapist qualification | Licensed child and adolescent psychotherapists, certified in the specific therapy |

Note: PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; PTS = post-traumatic stress.

Table 2.

Common techniques.

| Technique | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | Description | Child* | Caregiver(s)* |

| Psychoeducation | Providing information about the occurrence and frequency of traumatic events; normalizing stress reactions, feelings, and thoughts; explaining the therapeutic rationale and providing information about symptoms, diagnosis, and how treatment will address these; explaining the therapy procedures and the structure of the sessions | X (5) | X (5) |

| Relaxation | Acquiring skills for coping with the tension in everyday life that arises from the trauma-related stress reactions | X (4) | |

| Recording the critical experiences | Tracing back the critical experiences; ascertaining what happened, when it happened, and what symptoms, feelings, and thoughts are linked to it | X (4) | |

| Traumatic recollection | Starting to recall the traumatic memories; detecting arousal by activating the traumatic memory | X (5) | |

| Exposure | Repeated exposure to the traumatic memories (imaginal exposure, x = 3) and/or repeated exposure to feared and avoided situations associated with the traumatic memories (in vivo exposure, x = 2) | X (3) | |

| Homework | Practising at home with learned skills from the session(s) | X (3) | X (2) |

| Cognitive shifting | Discussing cognitions; attempting to influence or modify dysfunctional cognitions | X (4) | |

| Sharing the trauma story with others | Showing the young person’s finished product about the trauma story to people in the support system and communicating with them about the trauma | X (3) | X (3) |

| Future perspectives | Identifying the acquired skills and knowledge that can strengthen the resilience and future security of the young person and reduce the likelihood of recurrence | X (3) | X (1) |

| Termination | Evaluating the course of treatment in terms of the PTSD symptom scale and the learning effects; discussing how to deal with a recurrence of symptoms; marking the end of the therapy and the new start in the therapist’s absence | X (5) | X (4) |

Note: *(#) = number of protocols or manuals in which the technique appeared.

Table 3.

Common mechanisms.

| Element | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Description | Child* | Caregiver(s)* |

| Consolidation | Repetition of various domains, exercises, and skills during the therapy, to reinforce trauma processing | X (5) | X (2) |

| Trauma processing | Reframing; reorganization and sequence of fear-reducing changes that take place through exposure to the traumatic memory (inhibitory learning, x = 3; desensitization, x = 1) | X (4) | |

| Therapeutic relationship | Mutual attitudes, feelings, and trust between therapist and young person, parent, or system, and the ways in which these find expression during the treatment | X (5) | X (4) |

| Motivation | Sufficient drive in the young person to sustain the confrontation with the traumatic memory and its triggers | X (5) | |

| Affect modulation | Learning to recognize, label, and manage overwhelming and other negative emotions | X (5) | |

| Reciprocal integration | Altered feelings with respect to the critical experiences induce changes in cognitions, and vice versa | X (5) | |

| Sharing | Fostering support from the network; enhancing ties with significant others; fostering attachment relationships | X (3) | X (3) |

Note: *(#) = number of protocols or manuals in which the mechanism appeared.

An updated search was performed in October 2021, and yielded 611 additional articles. Title screening, followed by abstract screening, resulted in 12 potential eligible RCTs. Six articles mentioned one of the five included evidence-based therapies. None of the other articles provided RCTs that added to the therapies to meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, the updated search did not change the inclusion of the five selected evidence-based trauma therapies.

We found 10 common techniques (psychoeducation, relaxation, recording the critical experiences, traumatic recollection, exposure, homework, cognitive shifting, sharing the trauma story with others, future perspectives, and termination) and seven common mechanisms (consolidation, trauma processing, therapeutic relationship, motivation, affect modulation, reciprocal integration, and sharing) throughout the five evidence-based trauma therapies. The elements were considered common when present in three or more therapies. Notably, almost all of the identified therapeutic mechanisms – namely, consolidation, motivation, affect modulation, reciprocal integration, and therapeutic relationship – were considered present in all five therapies. This overlap in mechanisms could indicate that, although protocols stem from different theoretical backgrounds and apply partially different techniques, they address similar mechanisms.

4. Discussion

A substantial commonality of elements was found across the five evidence-based trauma therapies for children and adolescents. The present study makes use of the existing knowledge on trauma therapy in youth to reveal the commonalities, rather than emphasizing differences between psychotherapies. We argue that the elements that emerge from multiple evidence-based therapies may play an important role in therapy and have beneficial effects on trauma symptoms. These elements can be used for further research into their possible effectiveness.

The identification of the therapeutic relationship as a common mechanism is in line with clinical and epidemiological research that has shown that this relationship is a critical element in psychotherapy in general, promoting successful treatment outcomes (Labouliere, Reyes, Shirk, & Karver, 2017). The therapeutic relationship enhances a positive, stimulating, and safe environment in which therapeutic tasks and skill building can be performed (Noyce & Simpson, 2018). Accordingly, it has been highlighted in earlier research (described as ‘alliance’) as a common element in various youth therapies (Garland et al., 2008; van der Pol et al., 2019). Like therapeutic relationship, therapy motivation has been found to be a common mechanism in psychotherapy (described as ‘engagement’) (van der Pol et al., 2019). Motivation is considered to be a central element for the process of change in behaviour, thoughts, and feelings in psychotherapy (Westermann, Grosse Holtforth, & Michalak, 2019). Nevertheless, many different strategies exist to create and maintain motivation, and scarce information was available with regard to the operational process of motivation. Although it is specified in all five evidence-based trauma therapies, and was highlighted as important by the therapists, experts, and therapists with personal experience of trauma therapy, it would be a complex matter to extract a refined operational description from the manuals.

The treatment techniques that were found in all five evidence-based therapies were psychoeducation, recollection of traumatic memories, and techniques for termination of the therapy. Psychoeducation is an element that is present not only in trauma therapy but also in psychotherapies across the broader range of child psychiatric disorders (Garland et al., 2008; van der Pol et al., 2019). It enhances the clients’ knowledge and understanding of the psychiatric disorder and the consequent symptoms. Not only the child is in need of these insights, but informing parents or caregivers has also been shown to have a positive effect on their involvement during therapy (Martinez, Lau, Chorpita, & Weisz, 2017; Ryle & Kerr, 2020). Psychoeducation, tailored to child and parents, appears to be a potent technique in therapy that needs to be addressed during the therapeutic process. A common technique more specifically for trauma therapy was recollection of traumatic memories. This finding is important, since it could indicate that recalling and addressing such memories may be crucial for processing the traumatic experiences and addressing their symptoms. This element needs attention in the development and refinement of therapy addressing post-traumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents. As with psychoeducation, termination techniques are present in all therapies and appear to be critical not only in trauma therapy, but also in other psychotherapies for children (Macneil, Hasty, Conus, & Berk, 2010). Therapy termination can give the client a feeling of hope and confidence in facing future stressors, and it includes practical skills to deal with possible relapse. It can be perceived by adolescents or children as a sign that, by parting with the therapists, they are ready for the next step in their development (Ehlers et al., 2014).

Markedly, elements such as therapeutic relationship, therapy motivation, psychoeducation, and therapy termination appear to be common elements in previous studies for psychotherapy in youth (Garland et al., 2008; van der Pol et al., 2019), which could indicate that they are critical in psychotherapy for youth, and more research on the effectiveness of these elements is needed.

Our results show a broad range of parameters, suggesting the need for a tailor-made approach by the trauma therapist. Most therapies describe weekly sessions in their manual, but some recent research – and three out of the five consulted experts on the evidence-based trauma therapies – argued that therapies can be performed with a higher frequency of sessions and a shorter length of therapy. Such intensive trauma therapies are delivered within a few days, rather than months, and have shown promising results in both adults (Ooms-Evers, van der Graaf-Loman, van Duijvenbode, Mevissen, & Didden, 2021; van Pelt, Fokkema, de Roos, & de Jongh, 2021) and youth (King et al., 2000). The research reported here, by generating knowledge on the most potent elements, could contribute towards an empirically supported design for these intensive therapy days.

The current evidence-based trauma therapies are well constructed, and are supported from theoretical, practical, and empirical points of view, including effect sizes being sustainable over time (Lenz & Hollenbaugh, 2015; Morina et al., 2016). Nonetheless, existing protocols may not be effective for every individual child, and challenges with early termination are still being faced (Steinberg et al., 2019). As seen in clinical practice, therapists regularly incorporate various elements from their broad range of knowledge into the protocolled therapies to create a therapy suited to the individual child (Addis & Krasnow, 2000). By identifying the most potent elements, we can provide empirical support to therapists’ decisions to ‘borrow’ or incorporate additional effective elements to create the best fit for an individual child struggling with trauma symptoms (Holmes et al., 2018). Supervising therapists in doing so could lead to more flexible, effective, and efficient strategies in trauma therapy. Furthermore, we found elements that were not explicitly described in a manual or protocol, but which were nonetheless implicitly applied in a therapy by the therapist. One such element was parental involvement. Only two therapies, TF-CBT and TRT, include a protocol explicitly describing how to involve a parent or caregiver. However, many trauma therapists and most experts emphasized the importance of involving such significant adults during the therapy, either by including them in the sessions or by keeping them informed during the therapy process. Comparable research has highlighted parental involvement, or additional parenting skills components, as beneficial for various outcomes in children (such as reductions in anxiety, depression, and trauma symptoms) (Laor, Wolmer, & Cohen, 2001; Lenz & Hollenbaugh, 2015; Yasinski et al., 2016). Engaging non-offending caregivers in psychoeducation, skill building, and trauma processing will improve their own skills with respect to coping with trauma, and will foster understanding of the feelings, thoughts, and behaviour of the child (Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2010; Yasinski et al., 2016). There seems to be a discrepancy between what is written in the manuals or protocols and what is carried out in clinical practice by therapists concerning this caregiver involvement. Current findings show the importance of revising and refining existing protocols with evidence-based information on the involvement of important caregivers.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This is an initial study to identify the commonalities of trauma therapies for children and adolescents using a structured approach. The study made use of an existing framework, which was refined and expanded; for example, by adding therapists with personal experience of trauma therapy. The latter professionals both currently performed trauma therapy in practice and had previously experienced trauma and the process of trauma therapy themselves. By contributing such experiences, they could attest to the importance of certain elements or could refine the insights of others. An additional strength was that we included a diverse group of trauma therapists from throughout the Netherlands and consulted international trauma experts, in order to obtain the broadest possible view of trauma therapies.

The results of our study must be viewed in the light of some limitations. Current methodology cannot ensure that we identified all important elements. We selected only those therapies that met our strict inclusion criteria – at least three RCTs, at least one of them not conducted by protocol authors. Therapies not yet sufficiently investigated with RCT methodology may have been overlooked. Possibly, then, we may have missed further elements that have beneficial effects on therapy outcomes, but which did not emerge from our research as common features. Nonetheless, our rigorous approach and methodology – an initial literature review followed by knowledge contributions from therapists and experts – convinced us that we have identified today’s most prominent evidence-based therapies and their elements. Another limitation is our analysis of the elements, which was conducted by Dutch therapists and international experts, who are specialized in at least one of the five evidence-based therapies. This could lead to a less objective review of the elements in the protocols. To address this concern and minimize the bias, therapists were randomly divided in the Delphi group, and the process was overlooked by a researcher who was not trained in any therapy. Furthermore, the majority of therapists in the Delphi groups were not trained in the specific therapy that they assessed or were trained in multiple therapies (e.g. EMDR and TF-CBT).

We recognize a further limitation in our descriptions of common therapy elements. Parameters, techniques, and mechanisms were describable at different levels (very specific, intermediate, or very broad). We used a broad-to-intermediate conceptualization of elements to ascertain the common ground between the manuals. However, some elements are complex constructs, whereby the short-and-broad descriptions fail to do sufficient justice to the element’s complexity and cause details to go unmentioned. Moreover, a common elements approach does not address certain important details such as the intensity, frequency, and duration of each technique, which could be significant aspects in therapy success. Despite the limitations noted, we believe that this study could give an initial impetus to future research on trauma therapy. Potentially, one might even examine a wider range of psychotherapies that make use of similar elements.

4.2. Research and clinical implications

The results of our common elements study should contribute in a number of ways to research efforts and to clinical practice. First, the study creates a new basis for future research approaches, such as single-case experimental designs, MATCH studies, or precision psychiatry studies (Chorpita & Weisz, 2009; Friston, 2017; Tate et al., 2008). Those types of studies would enable us to test and follow up on the different elements, thus expanding our understanding of the mechanisms of action in trauma psychotherapy. Secondly, we found some overlap in elements with other therapies for children and adolescents (Garland et al., 2008; van der Pol et al., 2019), which underlines the importance of expanding this method to study other psychotherapies. We hope that this will enable us to eliminate inactive elements, incorporate effective elements, and create flexible modules to aid clinical practice in addressing psychiatric problems in children and adolescents in future.

A third implication is that our understanding of the active elements of trauma therapy could be of help in refining upcoming therapies, and that it could create an empirical base for assessing such new interventions on their potential in clinical practice. Fourthly, parental involvement has been highlighted as an important element in the therapies. More practical guidelines for the explication of such involvement appear to be needed for the future development of protocols and research. Finally, more flexible modules could be built to respond to psychological trauma in children located in areas with fewer resources, such as refugee camps or developing countries. The resources needed for evidence-based therapies are not always available in such areas, whereas trauma therapy has been shown to be effective in low-income countries and in culturally diverse groups (Unterhitzenberger et al., 2015). In this way, we could respond to the mental health burdens of children worldwide (Murray et al., 2012; Whiteford et al., 2013) and create viable psychiatric interventions to address their trauma symptoms.

5. Conclusion

In five evidence-based therapies for psychological trauma in children and adolescents, we identified a substantial number of commonalities. By highlighting these common elements, we have sought to create a basis for research and clinical practice with regard to targeted therapies tailored to each individual child and his or her support system. The identified elements could provide a useful benchmark for the further refinement and innovation of evidence-based trauma therapies. This could promote the creation of therapy modules that are more flexible and accessible for both therapists and clients, in every environment, from specialized psychiatric units to sites with meagre resources. Only with integrated knowledge can we enhance the effectiveness of child psychiatry and refine the trauma therapies for this vulnerable group of youth.

Supplementary Material

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created in this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the trauma therapists for their knowledge, thoughts, and time throughout the Delphi method; all the original authors of the researched evidence-based trauma therapies for their contribution; and Michael Dallas for his support in the English language.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding details

Not applicable.

References

- Addis, M. E., & Krasnow, A. D. (2000). A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes toward psychotherapy treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 331–339. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., Van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–340. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures Division of Clinical Psychology . (1995). Training in and dissemination of empiricallyvalidated treatments: Report and recommenda tions. Clinical Psychologist, 48(3), 24. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, R. J.-B., Jongsma, H. E., Kabadayi, M., & Billings, J. (2020). The effectiveness of psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in children, adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 50(10), 1598–1612. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, B. J., Phillips, S. D., Wagner, H. R., Barth, R. P., Kolko, D. J., Campbell, Y., & Landsverk, J. (2004). Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(8), 960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 5–20. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita, B. F., & Weisz, J. R. (2009). Modular approach to therapy for children with anxiety, depression, trauma, or conduct problems (MATCH-ADTC).

- Chrestman, K., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2008). Prolonged exposure therapy for adolescents with PTSD: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (1996). A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: Initial findings. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(1), 42–50. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2010). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for traumatized children. Evidence-based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents, 2, 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, W. E., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2007). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Runyon, M. K., & Steer, R. A. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety, 28(1), 67–75. doi: 10.1002/da.20744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehle, J., Opmeer, B. C., Boer, F., Mannarino, A. P., & Lindauer, R. J. (2015). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: What works in children with posttraumatic stress symptoms? A randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(2), 227–236. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0572-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., Grey, N., Wild, J., Liness, S., Albert, I., … Clark, D. M. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of 7-day intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD and emotion-focused supportive therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 294–304. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2005). Narrative exposure therapy: A short-term intervention for traumatic stress disorders after war, terror, or torture. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B. (2011). Prolonged exposure therapy: Past, present, and future. Depression and Anxiety, 28(12), 1043–1047. doi: 10.1002/da.20907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K. J. (2017). Precision psychiatry. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 2(8), 640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children's disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 505–514. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., Berglund, P. A., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(2), 113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves, P. M., & Thompson, R. F. (1970). Habituation: A dual-process theory. Psychological Review, 77(5), 419–450. doi: 10.1037/h0029810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, E. A., Ghaderi, A., Harmer, C. J., Ramchandani, P. G., Cuijpers, P., Morrison, A. P., … Craske, M. G. (2018). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on psychological treatments research in tomorrow's science. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(3), 237–286. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30513-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel, Z. E., Laska, K., Jakupcak, M., & Simpson, T. L. (2013). Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 394–404. doi: 10.1037/a0031474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., … Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, N. J., Tonge, B. J., Mullen, P., Myerson, N., Heyne, D., Rollings, S., … Ollendick, T. H. (2000). Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(11), 1347–1355. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouliere, C. D., Reyes, J., Shirk, S., & Karver, M. (2017). Therapeutic alliance with depressed adolescents: Predictor or outcome? Disentangling temporal confounds to understand early improvement. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(4), 600–610. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1041594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laor, N., Wolmer, L., & Cohen, D. J. (2001). Mothers’ functioning and children’s symptoms 5 years after a SCUD missile attack. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(7), 1020–1026. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, A. S., & Hollenbaugh, K. M. (2015). Meta-analysis of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for treating PTSD and co-occurring depression among children and adolescents. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 6(1), 18–32. doi: 10.1177/2150137815573790 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S. J., Arseneault, L., Caspi, A., Fisher, H. L., Matthews, T., Moffitt, T. E., … Danese, A. (2019). The epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(3), 247–256. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macneil, C. A., Hasty, M. K., Conus, P., & Berk, M. (2010). Termination of therapy: What can clinicians do to maximise gains? Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 22(1), 43–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2009.00443.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J. I., Lau, A. S., Chorpita, B. F., & Weisz, J. R.; Research Network on Youth Mental Health (2017). Psychoeducation as a mediator of treatment approach on parent engagement in child psychotherapy for disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(4), 573–587. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1038826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. M., Southam-Gerow, M. A., & Allin, R. B. (2008). Who stays in treatment? Child and family predictors of youth client retention in a public mental health agency. Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(4), 153–170. doi: 10.1007/s10566-008-9058-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina, N., Koerssen, R., & Pollet, T. V. (2016). Interventions for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C. J., Vos, T., Lozano, R., Naghavi, M., Flaxman, A. D., Michaud, C., … Memish, Z. A. (2012). Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380(9859), 2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyce, R., & Simpson, J. (2018). The experience of forming a therapeutic relationship from the client’s perspective: A metasynthesis. Psychotherapy Research, 28(2), 281–296. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1208373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooms-Evers, M., van der Graaf-Loman, S., van Duijvenbode, N., Mevissen, L., & Didden, R. (2021). Intensive clinical trauma treatment for children and adolescents with mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning: A pilot study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 117, 104030. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormhaug, S. M., & Jensen, T. K. (2018). Investigating treatment characteristics and first-session relationship variables as predictors of dropout in the treatment of traumatized youth. Psychotherapy Research, 28(2), 235–249. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1189617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijkers, C., Schoorl, M., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2019). Eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(6), 510–517. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, S. M., Bilsky, S. A., Dutton, C., Badour, C. L., Feldner, M. T., & Leen-Feldner, E. W. (2017). Lifetime histories of PTSD, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: Examining indirect effects via the roles of family and peer social support. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 49, 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum, B. O., & Schwartz, A. C. (2002). Exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 56(1), 59–75. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryle, A., & Kerr, I. B. (2020). Introducing cognitive analytic therapy: Principles and practice of a relational approach to mental health. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder, U., Ehlers, A., Elbert, T., Foa, E. B., Gersons, B. P., Resick, P. A., … Cloitre, M. (2015). Psychotherapies for PTSD: What do they have in common? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 28186. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.28186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, F. (1989). Eye movement desensitization: A new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 20(3), 211–217. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(89)90025-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, A. M., Layne, C. M., Briggs, E. C., Liang, L. J., Brymer, M. J., Belin, T. R., … Pynoos, R. S. (2019). Benefits of treatment completion over premature termination: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Psychiatry, 82(2), 113–127. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2018.1560584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate, L. R., McDonald, S., Perdices, M., Togher, L., Schultz, R., & Savage, S. (2008). Rating the methodological quality of single-subject designs and n-of-1 trials: Introducing the single-case experimental design (SCED) scale. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(4), 385–401. doi: 10.1080/09602010802009201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terr, L. C. (1983). Time sense following psychic trauma: A clinical study of ten adults and twenty children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 53(2), 244–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1983.tb03369.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker, R. H., & Wilson, S. A. (1999). Through the eyes of a child: EMDR with children. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Unterhitzenberger, J., Eberle-Sejari, R., Rassenhofer, M., Sukale, T., Rosner, R., & Goldbeck, L. (2015). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with unaccompanied refugee minors: A case series. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0645-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Oord, S., Lucassen, S., Van Emmerik, A., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2010). Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in children using cognitive behavioural writing therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 17(3), 240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pol, T. M., van Domburgh, L., van Widenfelt, B. M., Hurlburt, M. S., Garland, A. F., & Vermeiren, R. (2019). Common elements of evidence-based systemic treatments for adolescents with disruptive behaviour problems. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 862–868. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Pelt, Y., Fokkema, P., de Roos, C., & de Jongh, A. (2021). Effectiveness of an intensive treatment programme combining prolonged exposure and EMDR therapy for adolescents suffering from severe post-traumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1917876. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1917876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, S., Grosse Holtforth, M., & Michalak, J. (2019). Motivation in psychotherapy. In: Ryan R. M. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 417–441). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., … Vos, T. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 382(9904), 1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasinski, C., Hayes, A. M., Ready, C. B., Cummings, J. A., Berman, I. S., McCauley, T., … Deblinger, E. (2016). In-session caregiver behavior predicts symptom change in youth receiving trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(12), 1066–1077. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created in this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the trauma therapists for their knowledge, thoughts, and time throughout the Delphi method; all the original authors of the researched evidence-based trauma therapies for their contribution; and Michael Dallas for his support in the English language.