Abstract

The treatment landscape for gastric cancer (GC) is constantly evolving with therapies affecting all aspects of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) which need careful monitoring. While there are HRQoL measures designed specifically to capture issues relevant to patients with GC, these might be outdated and only relevant to patients in westernised cultures. This review identifies the patient-reported measures used to assess HRQoL of patients with GC and compares the HRQoL measures used across cultures including East Asia, where GC is more prevalent. We conducted a systematic review of publications between January 2001 and January 2021. A total of 267 papers were identified; the majority (66%) of studies involved patients from East Asian countries. Out of the 24 HRQoL questionnaires captured, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Cancer measure (QLQ-C30) was the most widely used (60% of all studies and 62% of those involving patients from East Asian countries), followed by its gastric cancer-specific module (QLQ-STO22, 34% of all studies and 41% from East Asia). Eight questionnaires were developed within East Asian countries and, of the 20 studies including bespoke questions, 16 were from East Asia. There were six qualitative studies. HRQoL issues captured include diarrhoea, constipation, reflux, abdominal pain and abdominal fulness or bloating, difficulty swallowing, restricted eating, and weight loss. Psychosocial issues related to these problems were also assessed. Issues relating to the compatibility of some of the westernised measures within East Asian cultures were highlighted.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Cross-cultural comparison, Health-related quality of life, Patient-reported outcome measures

Introduction

Gastric Cancer (GC) is one of the world’s most prevalent and deadliest cancers. In 2018, GLOBOCAN estimated 783,000 deaths attributable to GC [1]. In East Asia: Japan, China, Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan, and Macau, the incidence of GC is higher than in Europe [1, 2]. In 2018, South Korea, Mongolia, Japan, and China constituted the top four countries contributing the highest rates of GC per 100,000 of the population [1] and only one European country, Belarus, figured in the top ten. Due to routine screening for GC, patients from Asia are frequently diagnosed earlier than their European counterparts [2].

The treatment strategy for GC has dramatically changed in the last 10–15 years [2]. Endoscopic or surgical resection is recommended for early tumours [2]. New perioperative treatments have been introduced including the FLOT regimen, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and docetaxel, with improved survival compared to previous chemotherapy regimens [3]. New targeted agents include anti-angiogenic compounds, trastuzumab combined with platinum and fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy for HER-2-positive patients [2], as well as checkpoint inhibitors administered for advanced disease [4, 5]. Contemporary operative treatments using less-invasive approaches have also been introduced, including laparoscopic and robotic surgery. These systemic treatments and surgical advances may have more favourable outcomes in terms of treatment-related toxicities; however, they have unusual side effects previously not seen, including skin rashes, mucositis, and peripheral neuropathy [6, 7] while surgical-related side effects include ‘dumping syndrome’, reactive hypoglycaemia and chronic nutritional problems [8–11].

Treatment-related side effects can have a widespread impact on HRQoL, including physical health, psycho-social well-being, relationships, and independence [12–15]. Complications need to be monitored to implement management strategies, treatment modification or cessation, which is critical from the Healthcare Professional perspective [16, 17]. While the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) [18] represents the gold standard clinician rated tool for reporting severity of adverse events in clinical trials, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) consider HRQoL from the patient’s perspective. Examples of PROMS used in GC include the generic, non-cancer-specific, instruments, such as the Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form survey (SF-36) [19] and the EuroQol group EQ-5D [20] and the cancer-specific measures, such as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) [21] and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ) Core 30 (QLQ-C30) [22]. While these measures allow for comparisons across disease and tumour sites, they might overlook the specific and relevant concerns of patients with a particular cancer type such as GC.

Questionnaires designed to capture the HRQoL issues of specific relevance to patients with GC, include the EORTC and FACT gastric cancer-specific modules QLQ-STO22 [23, 24] and the FACT-Ga [25], both designed to supplement their core measures QLQ-C30 and FACT-G. The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GLQI) [26] and the Post-gastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45 (PGSAS-45) [27] represent condition specific measures, applicable to gastrectomized patients. These measures are predominantly westernised. The Quality of Life Instruments for Cancer Patients: STomach cancer (QLICP-ST) [28] was developed in response to reported shortcomings of Westernised measures using some items incompatible with Chinese culture, but to date has not been widely applied. Of the Westernised measures, the QLQ-STO22 and FACT-Ga are the most well-known within the field. The QLQ-STO22 includes 22 questions covering five domains: dysphasia; pain/discomfort; dietary restrictions; upper gastro-intestinal symptoms; specific emotional problems; and three single items: dry mouth; body image and hair loss. Although the QLQ-STO22 was developed in westernised cultures, including the UK, France, Germany, and Spain, its use is evolving [29], and it has now been used in multiple trials worldwide and clinically validated to assess the importance of included items in Japan [29, 30], Taiwan (Chinese version) [31], Mexico [32] and Iran [33].

Since GC is more prevalent in East Asia [2], it is important to understand whether the current HRQoL measures applied, like the QLQ-STO22 and FACT-Ga, are relevant to East Asian countries or whether any treatment or culturally specific adaptations or additions are needed. The way in which illness, such as cancer, is perceived and experienced is shaped by cultural and social context [34–36]. In a comparison between HRQoL of patients with breast cancer in the Netherlands and Japan, those from Japan reported better functioning while global quality of life scores were similar. It was suggested that in Japan, the quality of close relationships may contribute more to well-being than in European societies, while for women in western societies, achieving career goals and financial success or career may be more important. A further consideration relates to cross-cultural differences in access to healthcare resources and the economic burden of cancer experienced by patients. These differences need to be taken into account when considering HRQoL assessment across cultures. Studies exploring how HRQoL scales function across groups found differences in understanding [36]. HRQoL measures as well as differences in language assessment and linguistic equivalence including acceptability and interpretation of language [37].

This systematic review forms part of a programme of research addressing whether measures developed within westernised cultures, such as the STO22 cover the issues of relevance and importance to patients with GC in East Asia where GC incidence is highest. The following objectives are addressed in this review: 1. Identify the measures used to assess HRQoL in GC; 2. Examine cross-cultural differences in the assessment and reporting of HRQoL issues; 3. Identify challenges in the application of HRQoL measures across cultures.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [38] framework.

Searches and information sources

Searches for publications on patients with GC or esophagogastric Junction Carcinoma (EGJC) within 2 cm of the esophagogastric junction, ≤ 1 year since treatment were carried out. A detailed search of four databases: MEDLINE (Ovid SP), CINAHL Complete (EBSCO host), PsycInfo (EBSCO host) and EMBASE (EBSCO host) was conducted to search for literature published between January 2001 and January 2021. The start period of 2001 was used as a cut-off, based on the date of an earlier systematic review carried out by Vickery and colleagues on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group [23] to inform the development of the QLQ-STO22.

Search expressions were created using the Boolean operator OR between each term in each area and the Boolean operator AND between each area (see Table 1). Care was taken to adapt search expressions for different databases as necessary. The reviewers were also vigilant with respect to identifying new search terms during the review process.

Table 1.

Search terms used

| Area | Terms |

|---|---|

| Cancer |

Cancer Carcinoma Malignancy Neoplasm Oncology Tumor or Tumour |

| Gastric |

Gastric Stomach Gastrectomy |

| HRQoL |

Health-related quality of life HRQoL Quality of life QoL Outcome assessment (health care) |

| Outcomes/HRQoL outcome measures |

HRQoL outcome measures Patient-reported outcome measures |

Database searches were supplemented by manually checking references of selected full-text papers. Papers reporting cancers of multiple origins were included if separate data were reported for gastric cancer patients. Quantitative and mixed methods design studies were included as well as those using qualitative methods to capture HRQoL issues or patient-reported symptoms related to GC in any country. Conference proceedings, theses, cost-effectiveness studies and other papers reporting on studies which were not primary studies were excluded. Full details of inclusion criteria are provided in Table 2. All criteria had to be satisfied for a paper to be included.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| Papers reporting on HRQoL from the perspective of the patient and excluding clinician rated measures |

| Papers including patients diagnosed with GC (on or off treatment) and within or equal to 1 year of treatment. This includes patients with Upper gastro-intestinal tumours (stomach only) or patients with cancer within 2 cm of the esophagogastric junction. This will not include patients with upper gastro-intestinal tumours if they are oesophageal, or duodenum tumours or patients with oesophageal cancer not within 2 cm of the EGJC or where location is not specified, or patients with concurrent disease |

| This will include studies on patients with different diagnoses alongside GC, as long as HRQoL data for people with GC are reported separately |

| Papers reporting studies on adult patients aged 18 years and above diagnosed with gastric/stomach cancer |

| Papers reporting studies involving patients from all countries including East Asia (Japan, South Korea, North Korea China, Taiwan, Mongolia, and Macau) |

| Papers published between January 2001 and January 2021 |

| Papers published in English Language |

|

Studies including the following designs: 1. Randomised controlled trials |

| 2. Trials of quasi-experimental design (observational, case–control) |

| 3. Qualitative studies |

| 4. Mixed methods |

| Conference proceedings, theses, protocols, cost-effectiveness studies, studies reporting on animals and those not including primary data (e.g., reviews, case studies, expert opinion, theoretical papers, policy documents, guidelines, consensus, letters, editorials) will be excluded |

| Relevant grey literature from searches |

Paper selection

Database search results were imported into Endnote [X8] and de-duplicated. All references (titles and abstracts) were subsequently transferred to Rayyan QCRI (rayyan.qcri.org), an online systematic review management platform, and a thorough screening process conducted. In stage one, two independent reviewers [AR, SS] reviewed all title and abstracts in Rayyan against the inclusion criteria (Table 2) for full-text review and any discrepancies were resolved. In the event of any remaining doubt, the full paper was obtained. At stage two, all full texts were reviewed by AR and independently double-screened by a second reviewer [SS, MT, MG, KD, CM, BA]. A third reviewer resolved any eligibility disagreements. Inter-rater agreement percentage was reported.

Data extraction and analysis

A standardised form for data extraction, adapted from the minimum data checklist [39], was created in Microsoft Excel. All extracted data were reviewed by AR and checked by a second reviewer [SS]. Carefully targeted data extraction included: patient group, patient-reported measures used including HRQoL instruments and bespoke questions; geographical location of studies and patient-reported HRQoL issues and symptoms identified in results sections of papers. New issues that were either not covered by existing measures, or that authors reported as novel were also recorded. Measures used to evaluate these issues were recorded. Culturally specific factors were identified by reviewing the narrative provided by authors in the results and discussion sections of papers. Papers reporting studies from East Asia were categorised as those originating from countries based on the World Population review [40] (see Table 2 for the full list).

Results

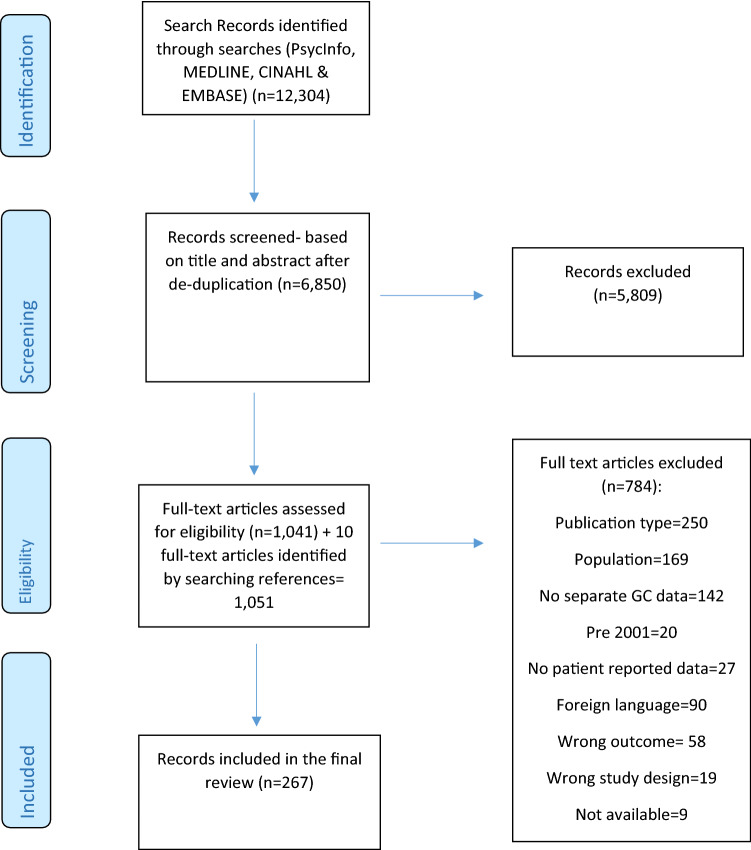

The database searches generated 12,304 hits (Fig. 1). During stage 1, 6850 titles and abstracts were screened and 5809 of these were excluded. There was a high level of inter-rater agreement between reviewers (98%; 6752/6850). Screening identified 1041 full-text papers for review and 10 identified through checking full-text paper references. Inter-rater agreement for full-text reviewing was 92.3%. Altogether, 1051 full-text papers were reviewed and 784 were subsequently excluded (of these, nine could not be obtained). The final review included 267 papers; 164 (61%) of these were from East Asia: including 60 from China, 48 Japan, 50 Korea, 3 Taiwan, 1 Japan/Taiwan, 1 Japan/Korea, 1 from China, Japan, and Korea. Eleven papers (4%) reported global studies, including at least one East Asian country.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of the selection process

The remaining papers represented 92 (34%) studies from countries outside of East Asia including: 10 from Germany, 7 Italy, 6 Poland, 5 Sweden, 4 the UK, 3 Spain, France, and Portugal, 2 Turkey, 7 Europe; 10 from Iran, 7 the USA, 4 Canada and India and 2 Colombia. The following countries included only one study: Finland, Vietnam, Singapore, Greece, Switzerland, Lithuania, Serbia, Ireland, Greece, Israel, and Australia. Papers reported mostly trials (127; 48%), e.g., comparing treatment protocols, nutritional supplements or management strategies; cohort studies (62; 23%); prospective studies (38; 14%); and the development and validation of HRQoL measures (9; 3%). Studies also reported on coping strategies, adjustment and acceptance of GC, nutritional status, unmet needs, and educational and self-care interventions. Six papers [23, 41–45], including 5 from non-East Asian countries, reported qualitative studies; three involved interviews with patients about symptoms experienced, such as gastrointestinal problems, fatigue, weight loss, and dietary restrictions, [41–43] and one about treatment preferences [44] whereby maintenance of self-care and minimising toxicities were rated as priorities. Two incorporated qualitative methodologies as part of a questionnaire development process [23, 45].

Measures used to capture the HRQoL issues of patients with GC

A total of 24 measures were used to assess a wide range of HRQoL concerns in patients with GC (Table 3), including generic (non-cancer-specific) measures (e.g., SF-36, EQ-5D) [19, 20], generic cancer measures (e.g., FACT-G, QLQ-C30,) [21, 22] GC-specific measures (e.g., FACT-Ga, QLQ-STO22) [23–25], measures specific to oesophageal or oesophago-gastric cancer (e.g., EORTC QLQ Oesophago-Gastric (QLQ-OG25), EORTC QLQ Oesophageal (QLQ-OES18) [46, 47]. In addition, measures used include those that can be applied to general gastrointestinal conditions [26, 48, 49] as well as those specific to symptoms and functioning post-gastrectomy [27] or general cancer treatment toxicities, such as nausea, vomiting and fatigue [50–52]. In addition, 20 studies (e.g., [53, 54] applied their own bespoke questions or measures often as a supplement to validated measures to capture additional treatment-related symptoms or psycho-social issues.

Table 3.

Application of measures by region of the world

| Measures | Areas (domains/items assessed) | Countries where measures are useda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia | Non-East Asian countries | East Asia and non-East Asian countries combined | ||

| Generic | ||||

| EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D) [20] | Mobility, Self-care, Pain, Usual activities, and Psychological status | 12 | 5 | 17 |

| Medical Outcomes Study Short-form (SF36/SF-36) [19] |

Physical and Social functioning, Physical and Emotional role limitations, Mental health, Energy, Pain, and General health perceptions Domains Physical and Mental component summaries |

2 | 1 | 3 |

| Spitzer Quality of Life Index [60] | Activity, Daily living, Health, Support of family and friends, Outlook | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| 15D (15-dimensional measure of HRQoL) [61] | Breathing, Mental function, Speech, Vison, Mobility, Usual activities, Vitality, Hearing, Eating, Elimination, Sleeping, Distress, Discomfort and symptoms, Sexual activity, Depression | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| World Health Organisation—Quality of Life WHOQOL Scale (also including WHOQOL-BREF) [62] | Physical health, Psychological health, Social relationships, Environmental health, | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Generic cancer | ||||

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (QLQ-C30) [22] |

Domains: Physical functioning, Emotional functioning, Social functioning, Role functioning, Cognitive functioning. Items: Fatigue, Pain, Nausea/Vomiting, Constipation, Diarrhoea, Insomnia, Dyspnoea, Appetite loss, Financial Difficulties, Global health, Global quality of life |

108 | 51 | 159 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (FACT-G) [21] | Physical well-being, Social/Family well-being, Emotional well-being | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy: Fatigue (FACT-F) [50] | Fatigue | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Quality of Life Questionnaire for Cancer Patients treated with anticancer drugs (QOL ACD) [27] | Daily Activities, Physical condition, Social activities, Mental status, Psychological status | |||

| Functional Living Index-Emesis (FLIE) [51] |

Nausea Vomiting |

2 | 0 | 2 |

| Gastric Cancer-specific | ||||

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire—Gastric Cancer (QLQ-STO22) [23, 24] |

Domains: Dysphagia, Dietary restriction, Pain, Reflux, Anxiety Items: Disease symptoms, treatment side effects, Dry mouth, Body image, taste problems |

72 | 18 | 90 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Gastric Cancer (FACT-Ga) [25] |

Gastric cancer subscale items: Weight loss, Appetite loss, Reflux, Dietary restrictions, Pain/discomfort when eating, Feeling full/heavy in the stomach, Stomach swelling/cramps, Dysphagia, Change in eating habits, Enjoyment of meals (socially), Interference of usual activities, Avoidance of going out, Worry over stomach problems, Discomfort/pain in stomach area, Flatulence, Diarrhoea, Fatigue, Weakness, Plans for the future |

3 | 4 | 7 |

| GC-PROM: Patient-reported outcome measure for Chinese patients with gastric cancer [55] | Physical: Abdominal symptoms, Systemic symptoms, Physical state, Independence; Psychological: Anxiety, Depressed, Pessimism; Social: Social support, Social adaptation; Therapeutic: Effectiveness, Satisfaction, Compliance, Drug side effects | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| KOQUSS-40: Symptom-Focused Quality of Life Questionnaire for Gastric Cancer Patients after Gastrectomy [45] | General quality of life, Indigestion, Dysphagia, Reflux, Dumping syndrome, Bowel habit change, Constipation, Psychological factors, Worry about cancer, Scar problems, Financial problems | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Korenaga’s Score Scale/Chew wun Wu special symptom score [56, 57] |

Appetite, Consistency of digested food, Volume of digested food, Frequency of eating, Eating time, Postprandial abdominal fullness, Heartburn, Diarrhea, and Constipation persistence, Insomnia, Body weight changes, Swallowing problems, Vomiting, Dizziness |

2 | 1 | 3 |

| Post-gastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45/037 (PGSAS45/PGSAS37) [27] | In addition to items from the SF-8 and GSRS: PGSAS-specific items: Bile regurgitation, sense of food sticking, Postprandial fullness, Early satiation, Lower abdominal pains, Dumping (early and late) symptoms. Dietary intake (amount and quality of ingestion), Work, Satisfaction with daily life | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| System of Quality of Life Instruments for Cancer Patients: Stomach Cancer (QLICP-ST) [28] | Physical, Psychological, Common symptoms and side effects | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Quality of life assessment based on Traditional Chinese Medicine for advanced gastric cancer (QLASTCM-Ga) [58] |

Unity of the body and spirit Correspondence between man and universe Specific module General module |

1 | 0 | 1 |

| Oesophageal-specific | ||||

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire—Oesophago-Gastric Modules (OG25) [46] | Domains: Dysphagia, Eating restrictions, Reflux, Odynophagia, Pain, Anxiety | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire – Oesophageal Cancer (OES18) [47] | Domains: Dysphagia, Eating, Reflux, Pain. Items: Saliva swallowing, Choking, Dry mouth, Taste, Coughing, Talking | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Gastrointestinal-specific | ||||

| Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GLQI) [26] | Gastrointestinal symptoms, Emotion, Physical function, Social function, Medical treatment | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) [48] | Reflux, Abdominal pain, Indigestion, Diarrhoea, Constipation | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Patient Assessment of Gastrointestinal Disorders-Symptoms Severity Index (PAGI-SYM) [49] | Heartburn/regurgitation, Nausea/vomiting, Fullness/early satiety, Bloating, Upper abdominal pain, Lower abdominal pain | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-QOL Questionnaires [59] | Daily activity, Diet, Psychological well-being | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Bespoke questions developed for the purpose of the study |

Post-gastrectomy symptoms Dumping syndrome symptoms Satisfaction Psychological functioning Social functioning |

16 | 4 | 20 |

aStudies often use more than one measure

The most widely used measure was the generic cancer QLQ-C30 [22] used in 159 (60%) studies, either as a standalone or supplemented with the GC-specific QLQ-STO22 in 90 (33%) studies. The generic, non-cancer-specific EQ-5D [20] was the next most used validated measure, however this was only used in 6% of studies. Other generic cancer and GC-specific measures were also used sparingly globally, including the FACT-Ga [21] used across 7 studies and two gastrointestinal measures: the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GLQI) [48] and the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) [27] used in six studies each.

In addition to bespoke questions added to match the researchers’ areas of interest, eight measures [27, 28, 45, 54–58], were developed in East Asia, and the PGAS45 [27] includes clinically important items selected by the Japan Post-gastrectomy Syndrome Working Party. Across all measures, the most widely assessed construct pertains to physical symptoms and this is particularly true for the GC or gastrointestinal specific measures which focus on gastrointestinal symptoms of disease and treatment such as gastrectomy. General physical symptoms assessed (e.g., by the EQ5D, QLQ-C30, FACT-G) [5, 21, 22] which are not necessarily cancer or GC-specific include mobility, nausea, vomiting, appetite and weight loss, diarrhoea, constipation fatigue, energy, sleeping problems, and pain. GC-specific symptoms assessed (e.g., by the FACT-Ga, QLQ-STO22, and the Symptom-Focused Quality of Life Questionnaire for Gastric Cancer Patients after Gastrectomy (KOQUSS-40)) [23–25] include reflux, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), dry mouth, eating and dietary restrictions, taste, abdominal pain and fullness, and dumping syndrome, with the PGSAS45 [27] distinguishing between early and late symptoms. The impact of symptoms on functioning is also assessed and, in particular, captured by the generic measures (e.g., by the EQ5D, SF-36, Spitzer Quality of Life Index, the 15D, QLQ-C30 and FACT-G) [19–22, 60, 61].

Psychological or emotional aspects of HRQoL, such as depression (15D, QLQ-C30, Patient-reported outcome measure for Chinese patients with gastric cancer (GC-PROM)) [22, 55, 61] worry and anxiety (QLQ-STO22, GC-PROM, OG25, Symptom-Focused Quality of Life Questionnaire for Gastric Cancer Patients after Gastrectomy (KOQUSS-40)) [23, 24, 31, 45] and distress (15D) [61], are also measured. The social domain covers social or family well-being (SF-36, World Health Organisation Quality of Life Scale (WHOQOL/WHOQOL-BREF), FACT-G,QLQ-C30) [19, 21, 22, 62], ability to go out and engage in social activities, social support (GC-PROM, Spitzer Quality of Life Index) [55, 60], and social enjoyment of meals [25]. Other HRQoL issues captured include sexual functioning (15D) [61], cognitive functioning (QLQ-C30) [22], financial difficulties (QLQ-C30, KOQUSS-40) [22, 45] body image (QLQ-STO22) [23, 24], outlook on life (Spitzer Quality of Life Index) [60], plans for the future (FACT-Ga) [25], and attitudes towards treatment (GC-PROM) [55]. One measure focused on HRQoL in relation to traditional Chinese Medicine [58].

Cross-cultural differences in the assessment and reporting of HRQoL issues

As mentioned above, the EORTC measures (QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22) were the most frequently used across all studies and this was also the case for studies conducted within East Asian countries. The QLQ-C30 was the measure of choice in 62% of studies involving patients from East Asia and the QLQ-STO22 in 41% of studies in East Asia. Of the eight measures developed within East Asian cultures, only the Korenaga Scale score/Wu’s adapted special score [56, 57] and the GERD QOL Scale [59] have been applied in studies involving patients outside of East Asia. In addition, of the 20 studies including bespoke questions or scales, 16 (80%) were conducted within East Asia.

Challenges to the assessment of HRQoL in GC across cultures

Cultural influences on HRQoL assessment were reported in terms of differences across cultures in treatment protocols, health disparities, access to health care resources, cultural views and practices, environmental and psycho-social issues, and linguistic equivalence. Potential environmental factors reported to impact HRQoL included pollution [63] and economic burden, especially for Chinese patients [35].

There were poignant cultural differences even surrounding the conceptualisation of cancer. In some East Asian studies cancer and malignancy were not culturally acceptable topics for discussion [32] and there was a social stigma linked to GC. Lee and colleagues [56, 64] compared HRQoL of Canadian Western and Korean patients and reported lower HRQoL in Korean patients. They suggested that as group participation is an integral part of Korean culture and cancer patients have been known to have to leave their jobs and miss group activities because of their cancer, this might be a significant impact for patients from Korea. Discussion of family and practical problems, spirituality, religion, and sexuality were reported as culturally sensitive and potentially upsetting for some communities [34, 35]. As part of a validation study of the FACT-Ga in Japan [65], the proportion of missing responses to the sex life question “I am satisfied with my sex life”, was highlighted with only 40.5% of respondents answering the question.

Several validation studies exploring the design and content validity of the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 promoted their validity for use in East Asian culture [30, 31, 66]. Whilst the overall validity of the most widely used GC-specific measures was confirmed, there were reported issues around linguistic equivalence in terms of acceptability and interpretation of language. For example, Huang and colleagues [31] suggested that the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 measures held the potential to positively impact understanding of well-being in patients from Taiwan, but that questions in the eating restriction scale, may hold different meaning for Taiwanese patients. Validation studies in Mexico [32] and Iran [33], also noted favourable outcomes on most scales of the QLQ-STO22, other than low internal consistency for “have you had trouble enjoying your meals?”. It was noted [33] that patients understood the translation of the question about enjoyment of meals but suggested that it might mean something different in Persian culture compared to in Western cultures. Restrictions to eating or meal-related issues, were widely documented in the literature and there were occasional adaptations to measures linked to East Asian food and culture. For example, Morita et al.’s validation study of the QLQ-STO22 [30], suggested validity for use in Japan, however, they recommended that the question referring to a ‘bloated feeling’ should be replaced with one referring to ‘retaining gas’. Furthermore, they speculated that problems linked to dysphagia and early satiety, might be linked to a staple Japanese food, rice, as patients might experience problems enjoying meals because of the need to eat a liquidised form of rice. Garland and colleagues [25] reported that patients found it difficult when questions included the word “stomach” if they had experienced a total gastrectomy and thus removed questions including this word from the Asian version of the FACT-Ga. Reference to cultural practices including traditional Chinese Medicine (including acupuncture, Tai Chi and herbal medicines) and its link to improved HRQoL was a noteworthy feature of several East Asian studies, principally from China [58, 67, 68]. Quan et al. [58] explored HRQoL issues for GC patients by implementing their HRQoL measure for traditional Chinese Medicine for advanced GC to measure the benefits of Chinese medicines for chemotherapy or surgical symptoms. The merits of a measure developed to capture the nuances of Chinese culture, the QLIP-ST [28] were highlighted in a comparison with the QLQ-STO22 [23, 24] in terms of enhanced compatibility with Chinese cultures, clearer structure, greater precision, and ease of interpretation [28].

Discussion

Our review captures the measures used to identify the full range of HRQoL issues faced by people with GC. The review generated 267 studies using patient-reported HRQoL measures with patients with GC who had recently finished treatment (within a year). Two thirds of these studies were from East Asia, which given the higher prevalence of GC in this part of the world is unsurprising [1, 2]. Measures developed with patients and health care professionals from European countries (QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22) were the most widely used and thus the patient-reported HRQoL issues reported in the studies are largely a function of the items included in these measures. Overall, studies conducted in East Asia applied more GC-specific measures, mainly using the QLQ-STO22, compared with studies conducted in countries outside of East Asia. This might again be accounted for by the high and emerging incidence and interest in GC treatment in East Asia, evidenced by the fact that 88% of studies in East Asia identified in this review were conducted since 2010, with the vast majority conducted post-2015. Our findings suggest that the measure of choice does not vary between countries and while the validity of the westernised measures has been queried in some papers (e.g., [28, 55, 64]), evidence suggests that these measures were widely accepted [30, 33]. In non-westernised countries, some content validity issues were noted especially around linguistic equivalence and problems in translating questions in the ‘eating restrictions’ [30, 31, 33]. Questions in these domains may need reassessing in countries outside of East Asia. Eight measures were developed for patients within East Asia and 16 of the 20 studies including bespoke measures were from East Asia suggesting that the existing and widely used westernised measures might have important omissions, such as symptoms relating to dumping syndrome or need adapting to suit East Asian culture.

In addition, the advent of new regimens [3–5] and surgical treatments [8–11] and specific side effects related to these (such as skin rashes, peripheral neuropathy, mucositis), may not be present in the existing HRQoL measures.

Several issues were only reported through ad hoc measures or in interview studies, including changing emotions surrounding food [41] and family communication issues [53]. These studies are particularly informative for providing additional depth, as patients have the freedom to talk about issues of concern to them, rather than responding to a set of pre-defined issues in a questionnaire.

Sexuality and sexual activity were rarely explored in the literature, irrespective of geographic region. Again, this might be a function of these issues not being asked about in the most widely used measures, such as QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22. Another possible explanation might link to the cultural unacceptability of discussing sexuality and sexual activity as a topic, particularly in East Asia and the difficulties in applying the sexual well-being scale of the FACT-Ga noted by Maeda and colleagues [65]. More research is needed to explore how acceptable patients with GC find it to be asked about the impact of their cancer on sexuality and whether there are geographical variations. Other overlooked issues included spiritual and religious topics and family communication, and, as with sexual functioning, there are potential cultural differences around acceptability about discussing these issues with less acceptability in some East Asian cultures. Further research is needed to quantify whether there are differences between non-Westernised and Western countries, surrounding these topics.

The impact of traditional Chinese Medicine on HRQoL was an expected feature of the East Asian literature given the high regard placed on traditional practices and one measure specific to capturing the HRQoL issues based on traditional Chinese Medicine [58] was identified in this review. There were also issues relating to language used with the perceived unacceptable use of the word stomach resulting in its removal from the Asian FACT-Ga [25]. Interestingly, the word stomach is also referred to in the widely used QLQ-STO22, but no studies reported this as problematic, although this may be because critiques of measures are rare. Similarly, preferences for using phrases such as ‘retaining gas’, rather than a ‘bloated feeling’ were occasionally voiced by patients [30]. Further research is needed to explore the cultural acceptability of HRQoL measures, and linguistic equivalence issues.

Limitations

During the selection process, 90 non-English language papers were excluded and many more were automatically excluded as a function of the filter option of database searches, thus we might have overlooked some pertinent issues and measures reported in studies in East Asia. Although we provide an overview of the measures used and thus HRQoL issues reported by patients with GC, our overview of issues is limited by the questions included in the measures; there were only six qualitative studies which offer additional insight into the HRQoL experience of patients. In addition, comparisons in the HRQoL of patients across cultures are limited; we were in a position to compare HRQoL measure usage across cultures rather than differences in the incidence of HRQoL concerns according to culture. This review is also limited by its descriptive focus, and the heterogenous nature of the studies, in terms of methods and measures used and focus and context of the studies. This makes it difficult to make comparisons between studies and ensure issues have not been missed. We have however provided a comprehensive overview of the measures used to assess patient-reported outcomes in GC patients from East Asian countries and countries outside of East Asia but given emerging treatments and new or adapted patient-reported HRQoL measures, we recognise the need for an on-going evaluation of patient-reported issues.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this review is the first to provide a comprehensive overview and comparison between East Asia and non-East Asia in HRQoL measures used for GC. Measures provide extensive coverage of HRQoL issues covering issues across physical, social, and psychological domains. The EORTC measures (QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22) are the most widely used irrespective of geographical location. While these measures benefit from extensive testing as part of their validation, they were not developed and tested with people from East Asia. Measures developed within East Asian cultures and bespoke questions and instruments offer improved sensitivity to the nuances of East Asian cultural and social contexts and allow for further exploration of psycho-social issues as well as symptoms relating to dumping syndrome or novel treatments. Further research is needed on the cultural relevance of HRQoL measures as well as further consideration of how we might make measures more culturally adaptable and acceptable.

Author contributions

ASD, AR, SS, MT and VV conceived the idea for the work and wrote the systematic review protocol. AR carried out the literature searches and AR, SS, MT, MG, CM, BA, and KD reviewed the manuscripts for inclusion/exclusion. All authors were involved in the writing and reviewing of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

This work supported by funding received from the European Organisation for Research And Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group awarded to SS, MT and VV (Grant reference 003–2019). MG received funding from the Norwegian Cancer Society (grant number 190188–2017). CM’s PhD. is funded by the Novo Nordisk UK Research Foundation. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised to correct the last author name.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/21/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s10120-022-01346-1

References

- 1.Rawla P, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: global trends, risk factors and prevention. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(1):26–38. doi: 10.5114/pg.2018.80001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):38–49. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Schmalenberg H, Kopp H-G, Haag GM, Luley KB, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with docetaxel, oxaliplatin, and fluorouracil/leucovorin (FLOT) versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine (ECF/ECX) for resectable gastric or gastroesophagealjunction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): a multicenter, randomized phase 3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15S):4004–4004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.4004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kataoka K, Dleersnijder A, Lordick F. Will molecular target agents enable the multidisciplinary treatment in stage IV gastric cancer? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(10):1835–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10111):2461–2471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitani S, Kadowaki S, Komori A, Kondoh C, Oze I, Kato K, et al. A phase II study of modified FOLFOX6 for advanced gastric cancer refractory to standard therapies. Adv Ther. 2020;37(6):2853–2864. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Li Y, Qi Y. Effect of glutamine-enriched nutritional support on intestinal mucosal barrier function, MMP-2, MMP-9 and immune function in patients with advanced gastric cancer during perioperative chemotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(3):3606–3610. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunobe S, Hiki N. Function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer: current status and future perspectives. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;25(2):77. doi: 10.21037/tgh.2017.09.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Jiang X, Huang H, Ding Z, Li C. Jejunal pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy is associated with better short-term absorption capacity and quality of life in early-stage gastric cancer patients. BMC Surg. 2018;18(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12893-018-0397-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong S, Park B, Noh H, Choi DJ. Herbal medicine for dumping syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1–12. doi: 10.1177/1534735419873404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarpellini E, Arts J, Karamanolis G, Laurenius A, Siquini W, Suzuki H, Ukleja A, et al. International consensus on the diagnosis and management of dumping syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(8):448–466. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCall MD, Graham PJ, Bathe OF. Quality of life: a critical outcome for all surgical treatments of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(3):1101–1113. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pruthi DS, Ahmad M, Gupta M, Bansal S, Nautiyal V, Saini S. Assessment of quality of life in resectable gastric cancer patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy as adjuvant treatment. South Asian J Cancer. 2018;7(1):16–20. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_196_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KW, Kim BJ, Kim MJ, Han HS, Kim JW, Park YI, Park SR. A multicenter randomized phase II study of docetaxel vs docetaxel plus cisplatin vs. docetaxel plus S-1 as second-line chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer patients who had progressed after cisplatin plus either S-1 or capecitabine. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(3):706–716. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang JK, Fang LL, Zhang DW, Jin Q, Wu XM, Liu JC, Zhang CD, Dai DQ. Type D personality in gastric cancer survivors: association with poor quality of life, overall survival, and mental health. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;52(1):81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alkhaffaf B, Blazeby JM, Bruce IA, Morris RL. Patient priorities in relation to surgery for gastric cancer: qualitative interviews with gastric cancer surgery patients to inform the development of a core outcome set. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034782. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkhaffaf B, Metryka A, Blazeby JM, Glenny AM, Adeyeye A, Costa PM, Diez Del Val I, Gisbertz SS, Guner A, Law S, Lee HJ, Li Z, Nakada K, Reim D, Vorwald P, Baiocchi GL, Allum W, Chaudry MA, Griffiths EA, Williamson PR, Bruce IA. Core outcome set for surgical trials in gastric cancer (GASTROS study): international patient and healthcare professional consensus. Br J Surg. 2021;108(10):1216–1224. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Common Terminology criteria for adverse events. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Accessed 4 Nov 2021.

- 19.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-SD: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Anna Med. 2001;33(5):337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vickery CW, Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Arraras J, Sezer O, Koller M, Rosemeyer D, Johnson CD, Alderson D, EORTC Quality of Life Group Development of an EORTC disease-specific quality of life module for use in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(8):966–971. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, Vickery C, Arraras J, Sezer O, Moore J, Koller M, Turhal NS, Stuart R, Van Cutsem E, D’haese S, Coens C, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal and Quality of Life Groups Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(15):2260–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garland SN, Pelletier G, Lawe A, Biagioni BJ, Easaw J, Eliasziw M, et al. Prospective evaluation of the reliability, validity, and minimally important difference of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-gastric (FACT-Ga) quality-of-life instrument. Cancer. 2011;117(6):1302–1312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmülling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82(2):216–222. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M, Kodera Y. Characteristics and clinical relevance of postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS)-45: newly developed integrated questionnaires for assessment of living status and quality of life in postgastrectomy patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18(1):147–158. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng Q, Wan CH, Luo JH, Tang XL, Li YF, Cun YL, Dai YG. Development of the system of quality of life instruments for cancer patients: stomach cancer (QLICP-ST) Ai Zheng. 2008;27(11):1212–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo J, Lee JH, Shim KN, Jung HK, Lee HM, Lee HK. Does the difference of invasiveness between totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy and laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy lead to a difference in early surgical outcomes? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):1836–1843. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morita S, Kaptein AA, Oba K, Sakamoto J. The domain structure of the EORTC QLQ-STO22 supported by Japanese validation data. Psychooncology. 2008;17(5):474–479. doi: 10.1002/pon.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang CC, Lien HH, Sung YC, Liu HT, Chie WC. Quality of life of patients with gastric cancer in Taiwan: validation and clinical application of the Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-STO22. Psychooncology. 2007;16(10):945–949. doi: 10.1002/pon.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oñate-Ocaña LF, Velázquez-Monroy N, Vázquez L, Espinosa-Mireles-de-Villafranca P, Núñez-Rosas E, Ovando-Lezama M, et al. Clinical validation of the EORTC QLQ-OG25 questionnaire for the evaluation of health-related quality of life in Mexican patients with esophagogastric cancers. Psychooncology. 2012;21(7):745–753. doi: 10.1002/pon.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadighi S, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, Sadighi Z. Quality of life in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomized trial comparing docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-FU (TCF) with epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU (ECF) BMC Cancer. 2006;6:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dein S. Explanatory models of and attitudes towards cancer in different cultures. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5(2):119–124. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer MJ, Inoue K, Matsuda A, et al. Cross-cultural comparison of breast cancer patients' Quality of Life in the Netherlands and Japan. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;166(2):459–471. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4417-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gotay CC, Blaine D, Haynes SN, Holup J, Pagano IS. Assessment of quality of life in a multicultural cancer patient population. Psychol Assess. 2002;14(4):439–450. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagano IS, Gotay CC. Ethnic differential item functioning in the assessment of quality of life in cancer patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:60. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ. 2009;339:2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Osoba D, Gotay C, Flechtner H, D’haese S, Zurlo A. Beyond the development of health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) measures: a checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials–does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision making? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(18):3502–3511. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Population Review https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/east-asian-countries. Accessed 4 Nov 2021.

- 41.Carey S, Laws R, Ferrie S, Young J, Allman-Farinelli M. Struggling with food and eating–life after major upper gastrointestinal surgery. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2749–2757. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1858-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carrillo GM, Santamaría NP. Life after a gastrectomy: Experience of patients with gastric cancer. Enferm Clin (Engl Ed) 2019;29(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellis J, Brearley SG, Craven O, Molassiotis A. Understanding the symptom experience of patients with gastrointestinal cancers in the first year following diagnosis: findings from a qualitative longitudinal study. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2013;44(1):60–67. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hofheinz R, Clouth J, Borchardt-Wagner J, Wagner U, Weidling E, Jen MH, Brück P. Patient preferences for palliative treatment of locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer and adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: a choice-based conjoint analysis study from Germany. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):937. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2975-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eom BW, Lee J, Lee IS, Son YG, Ryu KW, Kim SG, KOrean QUality of life in Stomach cancer patients Study group (KOQUSS) et al. Development and validation of a symptom-focused quality of life questionnaire (KOQUSS-40) for gastric cancer patients after gastrectomy. Cancer Res Treat. 2021;53(3):763–772. doi: 10.4143/crt.2020.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lagergren P, Fayers P, Conroy T, Stein HJ, Sezer O, Hardwick R, Hammerlid E, Bottomley A, Van Cutsem E, Blazeby JM, European Organisation for Research Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal and Quality of Life Groups Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(14):2066–2073. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Hammerlid E, Fayers P, Sezer O, Koller M, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(10):1384–1394. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(1):75–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1008841022998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rentz AM, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Tack J, Talley NJ, de la Loge C, Trudeau E, Dubois D, Revicki DA. Development and psychometric evaluation of the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal symptom severity index (PAGI-SYM) in patients with upper gastrointestinal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(10):1737–1749. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-9567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsumoto T, Ohashi Y, Morita S, Kobayashi K, Shibuya M, Yamaji Y, Eguchi K, Fukuoka M, Nagao K, Nishiwaki Y, Niitani H, CPT-11 Lung Cancer Study Groups West and East The quality of life questionnaire for cancer patients treated with anticancer drugs (QOL-ACD): validity and reliability in japanese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(5):483–493. doi: 10.1023/A:1015614505929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin AR, Pearson JD, Cai B, Elmer M, Horgan K, Lindley C. Assessing the impact of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on patients' daily lives: a modified version of the Functional Living Index-Emesis (FLIE) with 5-day recall. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11(8):522–527. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(2):63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Hokita S, Aoki T, Kashiwagi H, Hirakawa K, et al. Postoperative long-term evaluation of interposition reconstruction compared with Roux-en-Y after total gastrectomy in gastric cancer: prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Surg. 2011;202(3):247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawamura H, Takahashi N, Homma S, Minagawa N, Shibasaki S, Takahashi M, Taketomi A. Assessment of postoperative symptoms after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for stage I gastric cancer. Int Surg. 2014;99(5):645–649. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00111.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu X, Zhao F, Yu H, et al. GC-PROM: validation of a patient-reported outcomes measure for Chinese patients with gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:41. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korenaga D, Orita H, Okuyama T, Moriguchi S, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K. Quality of life after gastrectomy in patients with carcinoma of the stomach. Br J Surg. 1992;79(3):248–250. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu CW, Hsieh MC, Lo SS, Lui WY, P'eng FK. Quality of life of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma after curative gastrectomy. World J Surg. 1997;21(7):777–782. doi: 10.1007/s002689900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quan P, Zheng PY, You SF, Hua YQ, Song Y, Liu T, Wan CH, Lu JG. Clinical and psychometric validation of the quality of life assessment system for advanced gastric cancer based on traditional Chinese medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2016;22(8):581–588. doi: 10.1007/s11655-016-2465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan Y, Ching JY, Cheung CM, Tsoi KK, Polder-Verkiel S, Pang SH, Quan WL, Kee KM, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Wu JC. Development and validation of a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: the GERD-QOL questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(3):452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J, Chesterman E, Levi J, Shepherd R, Battista RN, Catchlove BR. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis. 1981;34(12):585–597. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(81)90058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):328–336. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Ma YM, Ba CF, Wang YB. Analysis of factors affecting the life quality of the patients with late stomach cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(9–10):1257–1262. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee KE, Lim KH. Differences in factors affecting the quality of life over time after the gastrectomy in patients with stage I gastric Cancer. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2020;43(3):241–248. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maeda H, Sato M, Kobayashi M, Takiguchi N, Yoshikawa T, Yoshino S, Yoshida K, Tsuburaya A, Sakamoto J, Morita S. Validity of the Japanese version of functional assessment of cancer therapy-gastric (FACT-Ga) and its sensitivity to ascites volume change: a retrospective analysis of Japanese clinical trial participants. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(11):4515–4521. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deng M, Lan Y, Luo S. Quality of life estimate in stomach, colon, and rectal cancer patients in a hospital in China. Tumour Biol. 2013;34(5):2809–2815. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0839-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun DZ, Jiao JP, Zhang X, Xu JY, Ye M, Xiu LJ, et al. Therapeutic effect of Jinlongshe Granule () on quality of life of stage IV gastric cancer patients using EORTC QLQ-C30: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21(8):579–586. doi: 10.1007/s11655-014-1950-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shu P, Tang H, Zhou B, Wang R, Xu Y, Shao J, Qi M, Xia Y, Huang W, Liu S. Effect of Yiqi Huayu Jiedu decoction on stages II and III gastric cancer: a multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98(47):e17875. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]