Abstract

Objective:

Clients who receive alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment experience variable outcomes. Measuring clinical progress during treatment using standardized measures (i.e., measurement-based care) can help indicate whether clinical improvements are occurring. Measures of mechanisms of behavioral change (MOBCs) may be particularly well-suited for measurement-based care; however, measuring MOBCs would be more feasible and informative if measures were briefer and if their ability to detect reliable change with individual clients was better articulated.

Method:

Three abbreviated measures of hypothesized MOBCs (abstinence self-efficacy, coping strategies, anxiety) and a fourth full-length measure (depression) were administered weekly during a 12-week randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with AUD. Psychometric analyses estimated how reliably each measure distinguished within-person change from between-person differences and measurement error. Reliability coefficients were estimated for simulated briefer versions of each instrument (i.e., instruments with fewer items than the already-abbreviated instruments) and rates of reliable improvement and reliable worsening were estimated for each measure.

Results:

All four measures had good reliability (.86-.90) for detecting within-person change. Many participants (41.4–62.5%) reliably improved on MOBCs from first to last treatment session. Reliable improvement on MOBCs was associated with reductions in percentage of drinking days at 3, 9, and 15-month follow-ups. Simulated briefer versions of each instrument retained good reliability for detecting change with only 3 (self-efficacy), 11 (coping strategies), 5 (anxiety), or 10 items (depression).

Conclusions:

Brief MOBC measures can detect reliable change for individuals in AUD treatment. Routinely measuring MOBCs may help with monitoring clinical progress.

Keywords: alcohol use disorder, measurement-based care, mechanisms of behavior change, routine outcome monitoring

There are a number of evidence-based treatments for alcohol use disorder (AUD; Ray et al., 2019). However, clinical outcomes for individual clients remain highly variable, even when they receive high-quality evidence-based treatments (Witikiewitz et al., 2017). Although randomized trials have provided valuable information about the average effectiveness of treatments across groups of individuals, less research has evaluated measurement tools that indicate whether individual clients are experiencing clinical improvements during treatment.

Research on mechanisms of behavior change (MOBCs) in AUD treatment has highlighted several variables that may serve as proximal indicators of clinical improvement. Several hypothesized MOBCs – including (but not limited to) abstinence self-efficacy, coping skills, depression, and anxiety – have been shown to improve during AUD treatment and to predict post-treatment drinking and functional outcomes (Holzhauer et al., 2020; Sliedrecht et al., 2019). These MOBCs also may mediate drinking outcomes across theoretically distinct treatments, suggesting they may reflect a subset of common factors that could indicate improvement for clients in a range of AUD treatments (Glasner-Edwards et al., 2007; Holzhauer et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2010, 2012; Litt et al., 2018; Wilcox & Tonigan, 2018).

This emerging understanding of MOBCs provides a unique opportunity to inform clinical care for individual clients. Specifically, since MOBCs are proximal indicators of treatment-related improvements and predictors of longer-term outcomes, measuring and monitoring changes in MOBCs throughout treatment could help indicate whether individual clients are improving in clinically important domains. For example, if MOBCs such as abstinence self-efficacy or use of alcohol-related coping strategies are routinely measured during treatment and indicate reliable improvement, it would suggest that the treatment is providing measurable benefits that may in turn facilitate better longer-term outcomes, which in turn could also help with making data-informed plans about the next steps in their treatment (e.g., identify factors that led to improvement in those MOBCs, solidify strategies for maintaining those improvements, reduce the frequency or duration of sessions, plan for termination, etc.). Likewise, if MOBCs do not reliably improve, it could indicate that the treatment is not providing its intended benefits, which likewise may help with making data-informed plans for addressing the lack of change (e.g., revisit treatment goals, modify treatment approaches, utilize adjunct treatments). Additionally, monitoring MOBCs may help emphasize the salience of non-drinking treatment targets such as self-efficacy, coping skills, depression, and anxiety in AUD treatment.

Routinely measuring clinical progress using standardized measures – also called measurement-based care – has been shown to help clinicians in non-AUD mental health settings more accurately detect improvements and exacerbations in client symptoms and more quickly adjust their treatment plans, while also yielding small-to-moderately larger treatment effect sizes (Boswell et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2018). These benefits could potentially apply to AUD treatment; however, limited testing and multiple implementation barriers have hampered the use of measurement-based care for AUD outside of clinical trials (Goodman et al., 2013).

Of particular relevance to the current study, one implementation barrier involves understanding the optimal ways to interpret the information provided by MOBC measures if they were to be administered routinely for measurement-based care. For example, many analyses have focused on differences in MOBC outcomes between groups (e.g., do clients in treatment A have greater increases in coping strategies than clients in treatment B?) and between-person associations of MOBCs with longer-term outcomes (e.g., do clients with greater increases in coping strategies have better drinking outcomes? See Finney et al., 2018 for discussion). In contrast, with measurement-based care it is usually more important to be able to evaluate whether MOBC measures reliably change within a single person over repeated measurements (e.g., has my client’s use of coping strategies improved since she started treatment?). Some degree of variability over time may be expected due to measurement error, and clinicians and clients may not know whether a change in scores indicates reliable change. Additionally, routinely administering MOBC measures may require the use of shorter instruments to reduce assessment burden, particularly if multiple domains are assessed repeatedly throughout treatment and if measures are to be completed outside of randomized trials where resources and expectations for completing assessments may be limited. Yet, reducing the number of items in an instrument typically reduces its reliability (Brennan, 2001), and thus there is a need to optimally balance brevity with reliability to administer instruments in a feasible but informative manner.

The present study addresses these measurement-related barriers by performing psychometric analyses of four MOBC measures that have been identified as particularly salient for women in AUD treatment (McCrady et al., 2020). Two of these MOBC measures (abstinence self-efficacy and coping skills) were shown in prior analyses from the same sample studied here to improve, on average, among abstinent and non-abstinent women during AUD treatment (Hallgren et al., 2019). Using generalizability theory (described below), our analyses specifically focus on (1) characterizing the reliability of each MOBC measure for detecting within-person change (and, importantly, disentangling this from measurement error and reliability attributable to between-person differences rather than within-person change), (2) characterizing cutoffs for reliable improvement or reliable worsening and quantifying rates of reliable change for each MOBC measure as it was administered during the study, (3) estimating the anticipated reliability for detecting change and anticipated rates of reliable change for simulated, briefer versions of each instrument, and (4) evaluating changes in percentages of drinking days from baseline to 3-, 9-, and 15-month follow-ups among participants with and without reliable change between the first and last attended treatment session.

Material and Methods

Participants

This study is a secondary analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial comparing group versus individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for women with AUD (Epstein et al., 2018; clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03589274). Participants were recruited through advertisements, flyers, referral outreach, and media and received up to 12 sessions of manual-guided, female-specific CBT for AUD. Both treatments (group and individual therapies) were abstinence-based and included standard CBT for AUD interventions including psychoeducation, motivational enhancement, and coping skills training with behavioral rehearsal. The female-specific protocol integrated interventions that targeted MOBCs that are particularly associated with alcohol use in women, including depression and anxiety (McCrady et al., 2020). Participants in both treatment conditions had significant and equivalent reductions in drinking that were maintained over a 12-month post-treatment period. There were no significant differences between the two treatment conditions on the MOBC measures examined here during the treatment period (Epstein et al., 2018).

Participants who completed within-treatment measures at least twice were included in the current study (n=128). Inclusion criteria included being female, ≥18 years old, having past-year DSM-IV alcohol dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), alcohol use within 60 days prior to initial screening, no psychotic symptoms in the past six months, no gross cognitive impairment, and no current physiological dependence on any illicit drug. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the clinical trial. All procedures were conducted in compliance with the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Drinking measures.

Timeline followback interviews (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 2003) were used to assess the percentage of drinking days (PDD), mean drinks per drinking day, and percentages of heavy drinking days (PHDD) over the 90 days prior to the last drinking day before the baseline interview. Within-treatment drinking was assessed using daily drinking logs, on which clients were instructed to record whether they drank and how much they drank on each day during the intervention period, which were supplemented with post-treatment (3 months after baseline) TLFB data when drinking logs were unavailable. Post-treatment drinking was assessed over a 6-month TLFB period 9 and 15 months after baseline.

Within-treatment weekly MOBC measures.

MOBCs were assessed using self-report questionnaires that participants completed before every session (up to 12 measurement occasions per participant). Participants were instructed to select the responses that best reflected their experiences over the prior week, including the day of the session. To reduce assessment burden, abbreviated instruments were used for three of the four MOBCs (abstinence self-efficacy, coping strategies, and anxiety). When abbreviated versions were used, the retained items were selected based on their high factor loadings in factor analyses, high correlations with full-scale scores, and strong internal consistencies of the retained items in cross-sectional baseline data collected in a previous clinical trial of women in AUD treatment (McCrady et al., 2016; see Epstein et al., 2018 for details; see supplement for a list of specific items retained in brief measures).

Abstinence self-efficacy was measured using items from the Situational Confidence Questionnaire-8 (Breslin et al., 2000), which was validated in outpatient AUD treatment settings. Five items from the eight-item version of the scale were administered at each session. The measure asks participants to rate their confidence in avoiding drinking across different situations that could pose a high risk for drinking (e.g., when experiencing urges or temptations, unpleasant emotions, or social pressures) on a scale of 0% to 100% confident. Item responses are averaged to produce total scores with a possible range of 0 to 100.

Coping strategies were assessed using items from the Coping Strategies Scale (Litt et al., 2003), which was validated with outpatients receiving AUD treatment. The full scale has 59 items, and our abbreviated measure retained 30 items. The measure asks participants to rate the frequency with which they used different coping strategies (e.g., “ask people not to offer me drinks” or “just wait and know that the urge to drink will go away”) on a scale of 1 (never) to 4 (frequently). Item responses are averaged, resulting in scores with a possible range of 1 to 4.

Depression and anxiety were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al., 1996) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck et al., 1988). The full versions of both measures include 21 items; for the present study, the full 21-item Beck Depression Inventory and an abbreviated 9-item Beck Anxiety Inventory were administered during treatment. Both measures ask participants to rate their symptoms over the past week on a scale from 0 (symptom is absent) to 3 (symptom is severe). Responses are summed for each instrument to create total scores ranging from 0 to 63 (depression) and 0 to 27 (anxiety).

Data Analysis

Psychometric analyses focused on characterizing the MOBC measures’ reliability for detecting within-person change and computing reliable change indices for individual clients. These analyses were guided by generalizability theory (Brennan, 1992, 2001), a statistical framework that can guide the partitioning of observed variance into component sources of “reliable” and “error” variance, estimate reliability coefficients and standard errors of measurement matched to the intended purpose of each measure (e.g., to detect within-person change), and estimate the anticipated reliability of measures with varying number of items. The sections below describe these analytic steps in greater detail.

Variance partitioning.

As a first step toward characterizing reliability of within-person change, the total variance observed for each MOBC measure across all items, participants, and occasions (σ2total) was partitioned into constituent, independent sources of variability, called facets. Random effect models estimated variance over participants (i.e., differences between individuals that were stable across occasions and items, σ2p), variance over measurement occasions (i.e., differences over occasions that were stable across people and items, σ2o), and variance over items (i.e., differences in item endorsement that were stable across participants and occasions, σ2i). Variance decomposition also accounted for all two-way interactions between these effects, including variance attributable to participants × occasions (i.e., differences between individuals in the amount of change between occasions, σ2po), variance attributable to participants × items (i.e., differences between individuals in their endorsement of specific items within the measure, σ2pi), variance attributable to items × occasions (i.e., differences in endorsement of specific items over occasions, σ2io), and residual error variance (σ2pio,e). The variances attributable to these facets may be derived using traditional ANOVA methods or, as in the current study, using maximum likelihood (Bates et al., 2015) to include all available information (e.g., including non-missing items in assessments where some items were skipped and including all participants even if they missed some measurement occasions).

Reliability of change.

In generalizability theory, it is possible to compute several reliability coefficients depending on the intended purpose of the measures and the sources of variance that are considered reliable versus error variance (Brennan, 1992, 2001). In the present study, our goal was to assess reliability for detecting within-person change for individual participants between two measurement occasions, and we therefore considered reliable variance to include variance over occasions (σ2o) and variance attributable to participants × occasions (σ2po), as these reflect change over time for each MOBC construct for the full-sample and for individual participants, respectively. We defined error variance to include variance attributable to changes in responses to specific items over time (σ2io) and the residual error variance (σ2pio,e), as these both reflect variability that is attributable to changes in responses to specific items over time (at the group and individual levels, respectively) that was not directly accounted for by changes in the MOBC construct. Variance components that did not include the occasion facet (i.e., σ2p, σ2i, and σ2pi) reflected sources of variability from facets that were stable over repeated measurement occasions and were neither considered reliable nor error sources of variability with relation to detecting within-person change for individual participants (i.e., they would not factor into the reliability of within-person change between measurement occasions, but some of these facets could factor into reliability coefficients focusing on the reliability of detecting between-person differences). After partitioning variance components, analyses estimated reliability of change coefficients by comparing the sum of the reliable sources variance (i.e., variance attributable to changes over occasions and changes over participants × occasions) to the sum of the reliable and unreliable sources variance as follows1, where ni indicates the number of items in the measure (Shavelson & Webb, 2006):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The standard error of measurement (SEM) for within-person change was computed as the square root of the error variance (σ2error). The SEM was then used to compute reliable change indices using the formula outlined by Jacobson and Truax (1991), which indicated whether the magnitude of the difference in an individual’s MOBC values between two time points reflected a reliable change from their first to their last available treatment session (ScoreT1 and ScoreT2) at the p < .05 level – that is, whether the magnitude of change was beyond what would be expected due to measurement error alone:

| (4) |

If the magnitude of an individual’s reliable change index is larger than ±1.96, it indicates a low probability2 (p < .05) that the observed change in scores is attributable to measurement error alone if the null hypothesis of no within-person change were true, in which case that null hypothesis may be rejected and the presence of reliable change may be concluded.

Reliability of shorter instruments.

Using the generalizability theory framework, the formulas above can be used to estimate the anticipated reliability of instruments with fewer items than those that were administered in the study, under the assumption that the items included in those even shorter versions are randomly sampled from the items that were administered in the study. When these assumptions hold, the anticipated error variances and reliability coefficients for an instrument with ni items (randomly sampled from the items administered) can be estimated using equations 2 and 3. In the present study, we estimate the anticipated reliability coefficients and standard errors of measurement for hypothetical shorter versions of each MOBC instrument (e.g., even briefer versions of the three already-abbreviated instruments and a briefer version of the one full-length depression instrument), assuming these items were to be randomly sampled from the items that were administered.

The anticipated rates of reliable improvement detectable on hypothetical versions of each instrument with fewer items were estimated using simulation methods that randomly sampled items to include on the briefer versions of each instrument. To simulate a briefer version of each instrument, ni items from the instrument were randomly selected, with ni ranging from 1 to the number of items on the administered instrument (for brevity, ni ranged from 1 to 15 on instruments with more than 15 items). Then, change scores, SEM values, and reliable change indices for the simulated briefer versions of each instrument were computed to identify the percentage of the sample with reliable change detected from the first to the last attended treatment session (i.e., indicating reliable improvement over the treatment period). To estimate the average rate of reliable improvement across different combinations of randomly sampled items, we repeated this process 100 times, with each repetition randomly sampling a new set of ni items from each instrument, after which we aggregated the average rate of reliable improvement across the 100 repetitions.

Results

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. On average, participants were just under 50 years old. Most participants were White, non-Hispanic, married/partnered, and employed. At baseline, participants drank on 66.48% of days, consumed a mean of 7.15 drinks per drinking day (SD=4.66), and drank heavily (≥4 drinks) on 57.93% of days. 41.4% of clients had at least one co-occurring Axis I or Axis II disorder at baseline. On average, participants completed 9.28 (SD=3.18) out of 12 possible pre-session assessments. Average values on the MOBC measures across all the within-treatment measurement occasions are presented in the Table.

Table 1.

Sample Descriptive Statistics (Total Sample N = 128)

| M or n | % or (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Age | 49.23 | (11.42) |

| White non-Hispanic, n, % | 104 | 81.3% |

| Married/partnered, n, % | 77 | 60.2% |

| Employed full or part time, n, % | 75 | 56.5% |

| Pre-treatment percentage of drinking days | 66.48 | (29.92) |

| Pre-treatment mean drinks per drinking day | 7.15 | (4.66) |

| Pre-treatment percentage of heavy drinking days | 57.93 | (31.47) |

| Current Axis I or Axis II disorder at baseline, n, % | 53 | 41.4% |

| Pre-session assessments completed (of 12 possible) | 9.28 | (3.18) |

| Mean values of MOBC measures across pre-treatment assessment occasions | ||

| Abstinence self-efficacy | 68.53 | (25.45) |

| Coping strategies | 2.83 | (0.53) |

| Depression | 10.10 | (9.63) |

| Anxiety | 3.91 | (4.88) |

Sources of Variability in MOBC Measures

The proportions of total variance accounted for by participant-, item-, and occasion-level facets and their interactions are shown in Table 2. For all measures, variance over occasions (σ2o) and variance between persons over occasions (σ2po), accounted for a relatively small but non-negligible percentage of the total variance observed (2.3 to 10.8% and 4.3 to 18.7%, respectively), indicating that a relatively small degree of the total variance observed was attributable to within-person change (i.e., reliable sources of variability). Variance attributable to changes in responses to specific items over time (σ2io) accounted for small percentages of total variance (0.3 to 0.8%) and the residual error (σ2pio,e) accounted for a large portion of total variance (20.6 to 32.0%), indicating that the latter (but not the former) source of measurement error contributed substantially to the observed variability in responses (i.e., a large source of unreliable variability). Variability attributable to stable differences across persons (σ2p), items (σ2i), or person-by-item interactions (σ2pi) collectively accounted for 45.5 to 68.8% of the total variance, indicating that much of the observed variability in responses was attributable to time-invariant facets that would not reflect within-person changes over time.

Table 2.

Variance Partitioning from Random Effect Models

| Abstinence Self-Efficacy | Coping Strategies | Depression | Anxiety | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Variance Component | Var. | % | Var | % | Var | % | Var | % |

|

| ||||||||

| Person (σ2p) | 365.6 | 40.1% | 0.19 | 16.7% | 0.14 | 29.0% | 0.15 | 24.6% |

| Item (σ2i) | 7.8 | 0.9% | 0.31 | 27.3% | 0.02 | 4.4% | 0.03 | 4.5% |

| Occasion (σ2o) | 98.7 | 10.8% | 0.03 | 2.7% | 0.01 | 2.3% | 0.02 | 3.2% |

| Person × Item (σ2pi) | 96.8 | 10.6% | 0.28 | 24.8% | 0.12 | 23.9% | 0.10 | 16.4% |

| Person × Occasion (σ2po) | 151.3 | 16.6% | 0.05 | 4.3% | 0.04 | 8.0% | 0.11 | 18.7% |

| Item × Occasion (σ2io) | 3.2 | 0.3% | 0.01 | 0.8% | 0.00 | 0.6% | 0.00 | 0.6% |

| Residual (σ2pio,e) | 187.3 | 20.6% | 0.27 | 23.4% | 0.16 | 31.8% | 0.19 | 32.0% |

| Total variance (σ2total) | 910.8 | 1.15 | 0.50 | 0.60 | ||||

Note. Percent column indicates percent of total variance across persons, items, and occasions that are accounted for by each facet.

Reliability of Within-Person Change

Table 3 displays estimated reliability of change coefficients and standard errors of measurement for each instrument as it was administered in the clinical trial (top row) and for simulated briefer versions of each instrument. There are no universal cutoffs for “acceptable” reliability, and requirements for acceptable reliability depend largely on the intended purpose of an instrument (Crocker & Algina, 1986). We encourage the interpretation of reliability coefficients on a continuum rather than as being categorically acceptable or unacceptable. However, for heuristic purposes and to guide our discussion, we consider reliability coefficients ≤ 0.49 as “poor” (i.e., less than half of the variance related to changes in scores over time is attributable to reliable change), 0.50 to 0.74 as “fair” (i.e., 50 to 74% of the variance related to changes in scores over time is attributable to reliable change), and ≥ 0.75 as “good” (i.e., at least 75% of the variance related to changes in scores over time is attributable to reliable change; see supplement for additional discussion). Coefficients reflecting poor, fair, and good reliability of change are shown in Table 3 using roman, italic, and bold fonts, respectively.

Table 3.

Reliability of Change Coefficients and Standard Errors of Measurement

| Abstinence Self-Efficacy | Coping Strategies | Depression | Anxiety | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| No. Items (ni) | Coef. | SEM | Coef. | SEM | Coef. | SEM | Coef. | SEM |

|

| ||||||||

| As administered* | .87 | 6.2 | .90 | 0.10 | .87 | 0.09 | .86 | 0.15 |

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | .57 | 13.8 | .22 | 0.53 | .24 | 0.40 | .40 | 0.44 |

| 2 | .72 | 9.8 | .37 | 0.37 | .39 | 0.28 | .57 | 0.31 |

| 3 | .80 | 8.0 | .47 | 0.30 | .49 | 0.23 | .67 | 0.25 |

| 4 | .84 | 6.9 | .54 | 0.26 | .56 | 0.20 | .73 | 0.22 |

| 5 | .87 | 6.2 | .59 | 0.24 | .61 | 0.18 | .77 | 0.20 |

| 6 | .63 | 0.22 | .66 | 0.16 | .80 | 0.18 | ||

| 7 | .67 | 0.20 | .69 | 0.15 | .82 | 0.17 | ||

| 8 | .70 | 0.19 | .72 | 0.14 | .84 | 0.16 | ||

| 9 | .72 | 0.18 | .74 | 0.13 | .86 | 0.15 | ||

| 10 | .74 | 0.17 | .76 | 0.13 | ||||

| 11 | .76 | 0.16 | .78 | 0.12 | ||||

| 12 | .78 | 0.15 | .79 | 0.12 | ||||

| 13 | .79 | 0.15 | .81 | 0.11 | ||||

| 14 | .80 | 0.14 | .82 | 0.11 | ||||

| 15 | .81 | 0.14 | .83 | 0.10 | ||||

Note. Coef.=reliability of change coefficient, SEM=standard error of measurement for within-person change. Coefficients reflecting poor, fair, and good reliability of change are shown using roman, italic, and bold fonts, respectively. Coefficients reflect the amount of variance related to changes in scores over time that is attributable to reliable change. See text for details. For consistency in the table, SEM values are always computed with the assumption that total scale scores are computed by averaging rather than summing items. For measures that are typically summed (i.e., depression, anxiety), the SEM must be multiplied by number of items administered to properly compute the SEM for summed scores.

As administered in the parent trial, the number of items was 5 (self-efficacy), 30 (coping strategies), 21 (depression), and 9 (anxiety).

As administered in the parent clinical trial, all four MOBC measures had good reliability for detecting within-person change. Changes in abstinence self-efficacy were measured with fair reliability using 1–2 items and good reliability using ≥3 items. Changes in coping strategies were measured with fair reliability using 4–10 items and good reliability using ≥11 items. Changes in depression were measured with fair reliability using 4–9 items and good reliability using ≥10 items. Changes in anxiety were measured with fair reliability using 2–4 items and good reliability using ≥5 items.

Percentages of Participants with Reliable Improvement

Table 4 displays the percentages of individuals who experienced reliable improvement (i.e., change between the first versus last session in the positive direction, with the magnitude of the reliable change index exceeding 1.96, reflecting reliable change over the course of treatment). The top row displays the percentage of participants with reliable improvement on the measures that were administered in the parent trial, and the remaining rows display the anticipated rates of reliable improvement that were estimated to be detected using simulated briefer versions of each instrument. As administered in the parent trial (top row of Table 4), 62.5% and 60.2% of participants reliably improved in abstinence self-efficacy and coping strategies at the p < .05 level, while 51.6% and 41.4% of participants experienced reliable improvement in depression and anxiety, respectively. Rates of reliable improvement on the four MOBC measures did not significantly differ between the group and individual treatment conditions, all χ2(df=1) ≤ 2.65, all p ≥ .10. Twenty-six clients (20.3%) had reliable improvement on all four MOBC measures, 27 (21.1%) reliably improved on three measures, 35 (27.3%) reliably improved on two measures, 21 (16.4%) reliably improved on only one measure, and 19 clients (14.8%) did not reliably improve on any of the MOBC measures.

Table 4.

Percentage of Sample with Reliable Improvement

| No. Items (ni) | Abstinence Self-Efficacy | Coping Strategies | Depression | Anxiety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| As administered* | 62.5% | 60.2% | 51.6% | 41.4% |

|

| ||||

| 1 | 39.0% | 16.6% | 9.2% | 12.5% |

| 2 | 47.9% | 16.8% | 22.1% | 27.0% |

| 3 | 54.5% | 26.3% | 31.3% | 22.2% |

| 4 | 59.6% | 35.9% | 24.9% | 30.1% |

| 5 | 62.5% | 31.5% | 31.2% | 35.4% |

| 6 | 37.9% | 36.8% | 40.2% | |

| 7 | 42.5% | 40.5% | 34.7% | |

| 8 | 37.6% | 34.8% | 38.0% | |

| 9 | 42.5% | 38.0% | 41.4% | |

| 10 | 45.1% | 41.6% | ||

| 11 | 48.4% | 44.4% | ||

| 12 | 44.3% | 47.5% | ||

| 13 | 47.7% | 41.5% | ||

| 14 | 50.3% | 43.7% | ||

| 15 | 52.1% | 46.0% | ||

Note.

As administered in the parent trial, the number of items was 5 (abstinence self-efficacy), 30 (coping strategies), 21 (depression), and 9 (anxiety).

The remaining rows in Table 4 display the estimated percentage of participants who were predicted to have improvement detected based on simulated briefer versions of each instrument. For each MOBC measure, most participants who had reliable improvement detected on the instruments as they were administered in the trial were likely to have also had reliable improvement detected on simulated shorter versions of each instrument. For example, a simulated self-efficacy measure with three randomly sampled items (i.e., the shortest simulated instrument with a “good” reliability of change coefficient) was estimated to detect reliable improvement in 70 participants (54.5% of sample), or 87.5% of the 80 participants who had reliable improvement detected on the five-item instrument that was administered in the study. Likewise, a simulated 11-item coping strategies measure detected reliable improvement in 62 participants (48.4% of sample), or 80.5% of the 77 participants who showed reliable improvement with the 30-item measure that was administered. Similarly, a simulated 10-item depression measure detected reliable improvement in 53 participants (41.6% of the sample), or 80.3% of the 66 participants who showed reliable improvement on the 21-item measure that was administered. A simulated 5-item anxiety measure detected reliable improvement in 45 participants (35.4% of full sample), or 84.9% of the 53 participants who showed reliable improvement on the 9-item measure that was administered.

Small subgroups of participants experienced reliable worsening on MOBC measures (i.e., change between the first versus last session in the negative direction, with the magnitude of the reliable change index exceeding 1.96), including 6 participants (4.7% of sample) for abstinence self-efficacy, 5 participants (3.9%) for coping strategies, 5 participants (3.9%) for depression, and 9 participants (7.0%) for anxiety. Among the remaining participants who showed no reliable change (in the positive or negative direction), there were sizeable subgroups who were technically unable to show reliable improvement on abstinence self-efficacy, depression, and anxiety because their first-session scores on these measures were already high enough (abstinence self-efficacy) or low enough (depression, anxiety) such that the amount of change required to obtain reliable improvement exceeded the bounds of the measurement scale (i.e., ceiling/floor effects). This included 15 participants (12.5%) for abstinence self-efficacy, 21 participants (17.2%) for depression, and 47 participants (37.5%) for anxiety; however, this did not occur for any participants on the coping strategies measure.

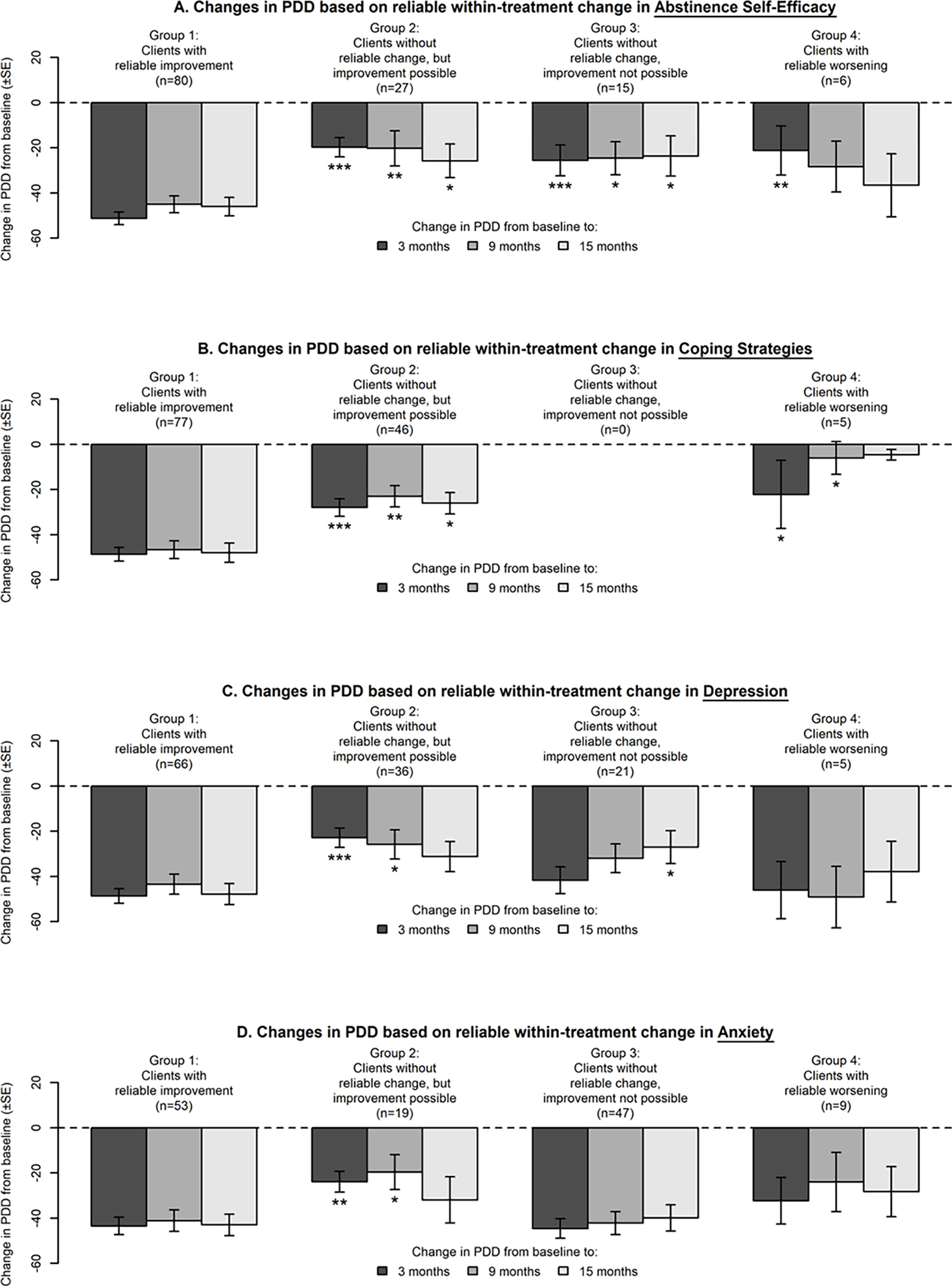

Changes in PDD Associated with Reliable Change in MOBCs

Figure 1 displays mean changes in PDD3 from baseline to follow-ups for different subgroups of clients based on whether their MOBC measures (1) reliably improved, (2) had no reliable change despite improvement being possible, (3) had no reliable change with reliable improvement not being possible (i.e., due to ceiling/floor effects), or (4) reliably worsened. Asterisks are displayed for the latter three subgroups when their changes in PDD significantly differed from changes in PDD for the subgroup with reliable improvement (i.e., significant subgroup × time interaction in a mixed two-way ANOVA).

Figure 1.

Changes in PDD for clients with and without reliable change in MOBCs during treatment. Note: Asterisks are displayed for subgroups with significant subgroup × time interaction in a mixed two-way ANOVA with reliable improved group (group 1) as the comparison subgroup.

Participants had greater reductions in PDD if they experienced reliable improvement within-treatment, compared to if they experienced no reliable change despite improvement being possible, on the following MOBCs: (a) abstinence self-efficacy (greater reductions in PDD at all follow-ups), (b) coping strategies (all follow-ups), (c) depression (3- and 9-month follow-ups), and (d) anxiety (3- and 9-month follow-ups; see Figure 1). Participants also had greater reductions in PDD if they experienced reliable improvement within-treatment, compared to when improvement was not possible because of floor/ceiling effects, on (a) abstinence self-efficacy (all follow-ups) and (c) depression (15-month follow-up). Participants had greater reductions in PDD if they experienced reliable improvement within-treatment, compared to experiencing reliable worsening within-treatment, on (a) abstinence self-efficacy (greater reduction in PDD at 3-month follow-up) and (b) coping strategies (3- and 9-month follow-ups).

Discussion

The present study utilized psychometric analyses of within-person change in MOBC measures to help bridge critical measurement-related gaps that partially inhibit the integration of MOBC research findings into routine clinical practice. Although research indicates that MOBCs often are expected to improve when clients benefit from AUD treatment, MOBCs are rarely measured in routine care outside of clinical trials. This implementation gap is exacerbated in part by a limited understanding of how well MOBC measures can reliably detect within-person change, limited ability to determine if individual clients have reliably improved on a given MOBC, and a reliance on relatively long instruments that may be prohibitive to routinely administer in some settings.

The MOBCs that were measured have been well-supported as mediators of AUD treatment (Glasner-Edwards et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2010, 2011; Litt et al., 2018; Wilcox & Tonigan, 2018). When administered repeatedly during treatment, these measures demonstrated good reliability in detecting within-person change, such that changes in scores could mostly be attributable to changes that individuals reliably experienced rather than being attributable to other sources of measurement error. Additionally, 41–63% of participants demonstrated reliable improvement on each of the different measures. Further analyses indicated that briefer versions of these instruments, composed of randomly sampled items from the items administered, are likely to maintain good reliability for detecting within-person change. Reliability coefficients tended to increase, then plateau, as instruments became longer; the percentages of clients with reliable improvement had a similar pattern but were more prone to fluctuate, likely due to limitations of a finite and moderately sized sample. Nonetheless, reliable improvement would likely have been detectable on considerably shorter instruments for at least 80% of the clients who showed reliable improvement on the longer instruments that were administered.

Implications for MOBC Research

MOBC research often aims to understand how individuals change during treatment. Yet, in many studies, MOBCs are often measured or analyzed at only one or a few time points (e.g., baseline and post-treatment) rather than repeatedly throughout the treatment period. As shown in our analyses, 45.5 to 68.8% of the total variance in responses on the MOBC measures that we evaluated was attributable to facets that do not vary over time during treatment. Therefore, research that utilizes MOBCs measured at a single time point (e.g., post-treatment MOBC measure as a predictor or outcome variable) is at considerable risk for confounding between- and within-person sources of variability, the former of which is usually larger despite the latter often being of greater interest for MOBC-related research questions. In contrast, measuring and analyzing MOBCs frequently throughout treatment (e.g., at every session) can allow researchers to untangle between- and within-person sources of variability, potentially providing more precision about how changes in MOBCs relate to research questions of interest. Measuring MOBCs frequently throughout treatment also may help researchers more precisely identify sources of within-person change in MOBCs, including how changes in MOBCs may be linked with specific treatment experiences or behavioral antecedents of reliable improvement (Hallgren, Wilson, & Witkiewitz, 2018). For example, previous research has identified pre-treatment characteristics of individuals and within-treatment session content that are associated with sudden changes in drinking, which are subsequently associated with long-term outcomes (e.g., Drapkin et al., 2015; Holzhauer et al., 2017); future research designs that include frequent administration of MOBC measures could further identify correlates of sudden, reliable changes in MOBCs using reliable change indices to further understand factors that potentially contribute to, and result from, sudden changes in MOBCs. Future research may also identify the optimal frequency of assessments (e.g., weekly, monthly) needed for detecting reliable improvement or for concluding that such improvements have become stable over time.

Our analyses of reliable change also can provide a useful, alternative metric for quantifying treatment-related improvements. Although the use of statistical significance testing based on group-level differences provides valuable information about clinical efficacy, the presence of statistical significance at the group level does not inherently indicate how many individual clients experienced reliable improvements (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). In contrast, the reliable change analyses here indicated that sizeable portions of the sample reliably improved in self-efficacy, coping strategies, depression, and anxiety. Moreover, the reliable change metric may provide a valuable tool for more effectively communicating clinical findings to clients, clinicians, and the public, as it provides an intuitive, understandable summary statistic (Jacobson & Truax, 1991; Wise, 2004). For example, few clients, clinicians, or other members of the general public are likely to understand how to interpret the p-values and standardized effect size statistics that are commonly reported in clinical trials (e.g., Cohen’s d, Hedge’s g), but many can understand findings such as “51.6% of women who received CBT for AUD experienced reliable improvements in their depression symptoms.” Communicating MOBC-related research findings using statistics that are understandable to clinicians, clients, and the general public could facilitate improved understanding of the impact of AUD treatments on non-drinking outcomes that are often highly relevant to clients (Neale et al., 2016) and could help convey the potential benefits of AUD treatment that may, in turn, help motivate clients, clinicians, and members of the general public to advocate for evidence-based treatments.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Measurement-based care – i.e., routinely monitoring treatment progress using standardized measures – has been shown to help clinicians more quickly identify treatment non-response and yields faster and larger clinical improvements for individuals receiving non-AUD mental health care (Boswell et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2018). However, measurement-based care rarely occurs in real-world AUD treatment outside of clinical trials (Goodman et al., 2013), with the exception that many clinicians monitor whether their clients report abstinence from alcohol and/or how much alcohol they have consumed, usually from client self-reports. Although drinking and abstinence can be informative aspects of measurement-based care, monitoring drinking and abstinence alone provides only a narrow range of information. Measuring MOBCs routinely during clinical care could provide a broader spectrum of information that may often be highly relevant. For example, many MOBCs reflect functional, recovery-related domains that are highly important to clients, and routinely measuring these domains during treatment could highlight them as clinically-important outcomes worth targeting directly in treatment in addition to (or regardless of) targeting abstinence or reduced drinking. Moreover, MOBCs are often proximal indicators of longer-term recovery and relapse (as further supported by the findings reported here), so monitoring MOBCs could provide more proximal indications of clinical improvements that may not be detectable by measuring abstinence and drinking alone. For example, some clients experience relapse as a significant but infrequent event, which may appear so sporadically that they occur rarely (or never) during treatment. Thus, abstinence and drinking may be limited indicators of the clinical improvements that may occur for these clients because it may take several months to determine if a change in one’s drinking pattern has occurred. MOBCs, in contrast, may be more capable of detecting incremental change that may be less noticeable than changes between abstinence and non-abstinence. Additionally, many clients initiate abstinence prior to starting treatment (e.g., up to 44% of clients in AUD clinical trials; Epstein et al., 2005; Hallgren et al., 2019) and monitoring abstinence alone for these individuals would leave little room to detect further improvements due to floor effects, even though these MOBC measures often continue to improve after initiating abstinence (Hallgren et al., 2019).

Mobile devices and integration of client-reported outcome measures in electronic health records create opportunities for routinely measuring and tracking MOBCs with reduced burden to clinicians and clients. For example, most clients in addiction treatment programs own smartphones (Tofighi et al., 2019) on which they could complete brief MOBC-related questionnaires on a routine basis, within or outside of the clinics where they receive treatment. Electronic health record systems and other software can allow client-reported outcomes to be entered, automatically scored, and graphed for clinicians and clients to evaluate trends over time for individual clients, and graphical or narrative summaries could potentially be generated automatically to indicate whether individual clients have experienced reliable change. Reviewing these data and being aware of reliable improvement, reliable worsening, or lack of reliable change could provide valuable data to help guide clinical discussions about potential reasons for such changes (or lack of changes) and whether adjustments to treatment-related goals, approaches, or levels of care may be needed.

Limitations and Strengths

The present study has several limitations. First, there are important measurement-related limitations. For most instruments, we utilized briefer versions of longer, validated instruments by using subsets of items to reduce assessment burden related to completing measures every week. The items we retained were selected for their strong psychometric properties (based on between-subject analyses), and it is unclear how substantially our results would have differed had we used the full versions of each instrument. Second, measures were administered only for research purposes and were not relayed back to clinicians and clients (i.e., not used for measurement-based care). It is possible that responses could have differed if results were fed back to clients and clinicians for measurement-based care. Third, there are limitations in the generalizability of the sample. The sample was entirely female (by design) and predominantly non-Hispanic White. Therefore, results of the study may not generalize to men or women of color in AUD treatment. Fourth, the participants were enrolled in a well-controlled trial of high-fidelity CBT, which yields high internal validity for testing treatment effects but reduces generalizability to real-world AUD treatment settings, where treatment modalities and fidelity often vary considerably. The sample size was selected to test the primary clinical trial outcomes and was somewhat smaller than what is often desired for psychometric testing. Last, the estimated reliability indices for the simulated shorter versions of each MOBC instrument are reflective of their approximate expected values if items were randomly sampled from the population of administered items, but we did not administer the shorter versions and it is possible that the actual reliability of shorter instruments could differ, depending on the specific items selected or due to changes in client response patterns on shorter instruments. Thus, the findings of the current paper provide a launching point for further investigating specific, brief MOBC measures that can be used specifically for measurement-based care in diverse real-world settings.

The present study also had several strengths. The entirely female sample is a strength, as women typically are under-studied in AUD treatment research. Although participants with physiological dependence on illicit drugs or psychotic symptoms were ineligible, other mental health diagnoses were not exclusionary and rates of Axis I and II psychopathology in the sample were consistent with those for women receiving AUD care in real-world settings. Rigorous treatment fidelity analyses assured that the CBT program was delivered to clients as intended and as directed by treatment manuals. MOBC measures were derived from well-validated questions and administered at every treatment session, supporting finer-grained partitioning of variability over time than is usually available. Each client completed over nine repeated measures of MOBCs, on average. Many of the MOBCs that we measured have been demonstrably related to drinking outcomes across a variety of treatment modalities (e.g., CBT, digital therapies, pharmacotherapies, twelve-step programs; Acosta et al., 2017; Glasner-Edwards et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2010, 2011; Roos et al., 2020; Wilcox & Tonigan, 2018), suggesting that measuring these MOBCs as part of measurement-based care could provide valuable information across a variety of treatment approaches. The use of measurement-based care is itself also theory-agnostic and can be incorporated into almost any treatment modality (Scott & Lewis, 2015).

Conclusion

Every year over 650,000 individuals in the US receive AUD treatment in specialty addiction treatment facilities (SAMHSA, 2019) and each of these individuals experiences a unique clinical course. Routinely measuring MOBCs has the potential to help indicate the extent to which that clinical course includes improvement on key treatment targets that confer a higher likelihood of better longer-term drinking and functional outcomes. The analyses conducted here bridge critical measurement-related gaps for detecting reliable within-person change in MOBCs during AUD treatment. Although these measurement-focused analyses support the ability of measures to detect within-person change on four pertinent MOBCs, additional research is needed to address additional technological, clinical, and organizational barriers to implementing measurement-based care within AUD treatment, particularly outside of clinical trials. Incorporating routine and systematic measurement of treatment progress using psychometrically sound measures may provide a framework for delivering more personalized and data-driven care for individuals with AUD.

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance.

Brief measures of abstinence self-efficacy, coping strategies, depression, and anxiety reliably measure within-person clinical changes during alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment.

The 41–63% of clients who showed reliable improvement in these measures during outpatient AUD treatment had the largest reductions in drinking days after treatment.

Measuring these constructs during AUD treatment can be way of delivering measurement-based care, an evidence-based practice that is rarely utilized in routine AUD treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) awards K01AA024796, R21AA028073, and R01AA017163 and Dept of Veteran Affairs, Veteran Health Administration CSR&D grant CX001951. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, or the U.S. government.

Appendix: Data Transparency Statement

Two other publications have resulted from the dataset analyzed in this study. One of these publications presented the primary results of the parent randomized clinical trial, comparing differences between intervention conditions (group vs. individual CBT). The other publication examined temporal associations between week-by-week changes in mechanisms of change measures studied here in relation to the initiation of abstinence from alcohol. These prior studies included analyses of PDD, PHDD, and the MOBC measures studied in this manuscript (abstinence self-efficacy, coping strategies, depression, and anxiety). However, the results presented here differ considerably, as they answer measurement-related questions about how to most reliably measure within-person changes in mechanisms of change and whether reliable change indices from first to last session predict better drinking outcomes.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: All authors declare no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

In our study, we assume changes in MOBCs are assessed by comparing measures from two independent occasions, and therefore the number of occasions that would typically be included in the denominators of equations 1 and 2 is equal to 1 and is therefore omitted from formulas.

The cutoff of 1.96 reflects a critical z-value (two-tailed) for a 0.05 alpha level; other critical z-values may be substituted for different alpha levels if higher or lower thresholds for confidence in reliable change are preferred.

PDD was selected as the primary drinking outcome because the parent trial had an explicit goal of abstinence. Analyses of PHDD were largely similar to the analyses of PDD shown here (see supplement).

References

- Acosta MC, Possemato K, Maisto SA, Marsch LA, Barrie K, Lantinga L, ... & Rosenblum A (2017). Web-delivered CBT reduces heavy drinking in OEF-OIF veterans in primary care with symptomatic substance use and PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 48(2), 262–276. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, & Walker SC (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1). doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, and Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, and Brown GK (1996). Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Kraus DR, Miller SD, & Lambert MJ (2015). Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: Benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychotherapy Research, 25(1), 6–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan RL (1992). Generalizability theory. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 11(4),27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan RL (2001). Multifacet universes of generalization and D study designs. In Generalizability Theory (pp. 95–139). Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Breslin FC, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, & Agrawal S (2000). A comparison of a brief and long version of the Situational Confidence Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(12), 1211–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker L & Algina J, 1986. Introduction to Classical and Modern Test Theory. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, FL 32887. [Google Scholar]

- Drapkin M, Epstein EE, McCrady B, & Eddie D (2015). Sudden gains among women receiving treatment for alcohol use disorders. Addiction Research & Theory, 23(4), 273–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, McCrady BS, Hallgren KA, Cook S, Jensen N, Graff F, Hildebrandt T, Holzhauer CG, & Litt MD (2018). Individual versus group female-specific cognitive-behavior therapy for alcohol use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 88, 27–43. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW (2018). Identifying mechanisms of behavior change in psychosocial alcohol treatment trials: Improving the quality of evidence from mediational analyses. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(2), 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner-Edwards S, Tate SR, McQuaid JR, Cummins K, Granholm E and Brown SA (2007). Mechanisms of action in integrated cognitive-behavioral treatment versus twelve-step facilitation for substance-dependent adults with comorbid major depression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(5), 663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JD, McKay JR and DePhilippis D (2013). Progress monitoring in mental health and addiction treatment: A means of improving care. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(4), 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren KA, Epstein EE, & McCrady BS (2019). Changes in hypothesized mechanisms of change before and after initiating abstinence in cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with alcohol use disorder. Behavior Therapy, 56, 1030–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren KA, Wilson AD, & Witkiewitz K (2018). Advancing analytic approaches to address key questions in mechanisms of behavior change research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(2), 182–189. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzhauer CG, Epstein EE, Hayaki J, Marinchak JS, McCrady BS, & Cook SM (2017). Moderators of sudden gains after sessions addressing emotion regulation among women in treatment for alcohol use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 83, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzhauer CG, Hildebrandt T, Epstein EE, McCrady BS, Hallgren KA, & Cook S (2020). Mechanisms of change in female-specific and gender-neutral cognitive behavioral therapy for women with Alcohol Use Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS and Truax P (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Stout RL and Pagano M (2012). Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: A multiple mediator analysis. Addiction, 107(2), 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Stout RL, Magill M, Tonigan JS and Pagano ME (2010). Mechanisms of behavior change in alcoholics anonymous: Does Alcoholics Anonymous lead to better alcohol use outcomes by reducing depression symptoms? Addiction, 105(4), 626–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ, Beck AK, Baker AL, Deane FP, Hides L, Manning V, ... & Oldmeadow C (2020). Feasibility of a mobile health app for routine outcome monitoring and feedback in mutual support groups coordinated by SMART Recovery Australia: Protocol for a pilot study. JMIR Research Protocols, 9(7), e15113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, & Kleinstäuber M (2018). Collecting and delivering progress feedback: A meta-analysis of routine outcome monitoring. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Cooney NL, & Kabela E (2003). Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, & Tennen H (2018). Treatment response and non-response in CBT and network support for alcohol disorders: Targeted mechanisms and common factors. Addiction, 113(8), 1407–1417. doi: 10.1111/add.14224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, & Fokas KF (2020). Treatment interventions for women with alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Hallgren KA, Cook S, & Jensen NK (2016). Women with alcohol dependence: A randomized trial of couple versus individual plus couple therapy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(3), 287–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J, Vitoratou S, Finch E, Lennon P, Mitcheson L, Panebianco D, ... & Marsden J (2016). Development and validation of ‘SURE’: A patient reported outcome measure (PROM) for recovery from drug and alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 165, 159–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Bujarski S, Grodin E, Hartwell E, Green R, Venegas A, ... & Miotto K (2019). State-of-the-art behavioral and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(2), 124–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Carroll KM, Nich C, Frankforter T, & Kiluk BD (2020). Short-and long-term changes in substance-related coping as mediators of in-person and computerized CBT for alcohol and drug use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 212, 108044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavelson RJ, & Webb NM (2006). Generalizability Theory. In Green JL, Camilli G, & Elmore PB (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (p. 309–322). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sliedrecht W, de Waart R, Witkiewitz K and Roozen HG (2019). Alcohol use disorder relapse factors: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (2003). Alcohol consumption measures. In Allen JP, & Wilson V (Eds.), Assessing alcohol problems (pp. 75–99) (2nd ed.). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (2019). Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Tofighi B, Leonard N, Greco P, Hadavand A, Acosta MC & Lee JD (2019). Technology use patterns among patients enrolled in inpatient detoxification treatment. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 13(4), 279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox CE and Tonigan JS (2018). Changes in depression mediate the effects of AA attendance on alcohol use outcomes. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(1), 103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise EA (2004). Methods for analyzing psychotherapy outcomes: A review of clinical significance, reliable change, and recommendations for future directions. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82(1), 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Pearson MR, Hallgren KA, Maisto SA, Roos CR, Kirouac M, ... & Heather N (2017). Who achieves low risk drinking during alcohol treatment? An analysis of patients in three alcohol clinical trials. Addiction, 112(12), 2112–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.