Abstract

Seed germination is an important agronomic trait that affects crop yield and quality. Rapid and uniform seed germination traits are required in agricultural production. Although several genes are involved in seed germination and have been identified in Arabidopsis and rice, the genetic basis governing seed germination in maize remains unknown. Herein, we conducted a genome-wide association study to determine the genetic architecture of two germination traits, germination speed, and consistency, in a diverse panel. We genotyped 321 maize inbred populations with tropical, subtropical, or temperate origins using 1219401 single-nucleotide polymorphism markers. We identified 58 variants that were associated with the two traits, and 12 of these were shared between the two traits, indicating partial genetic similarity. Moreover, 36 candidate genes were involved in seed germination with functions including energy metabolism, signal transduction, and transcriptional regulation. We found that favorable variants had a greater effect on the tropical subpopulation than on the temperate. Accumulation of favorable variants shortened germination time and improved uniformity in maize inbred lines. These findings contribute significantly to understanding the genetic basis of maize seed germination and will contribute to the molecular breeding of maize seed germination.

Keywords: genome-wide association study, germination speed, germination consistency, molecular breeding, maize

Introduction

As the primary food source, crops have supported human development and progress over several 1,000 years. The life cycle of the majority of crops begins with seed germination and continues to juvenile and adult vegetative stages, reproductive stages, and seed production. Seed vigor is an important agricultural trait that affects crop yield and quality directly and indirectly (Tekrony and Egli, 1991; Ellis, 1992; Larsen et al., 1998). Seed germination is an important component of seed vigor, which is defined as the potential activity of the seeds (Perry, 1978; Association of Official Seed Analysis, 1983).

The process of seed germination can be categorized into three physiological phases from the mature dry seed to the protrusion of the radicle. During the initial phase (Phase I), dry seeds rapidly absorb water through physical absorption until the seed’s cell is hydrated. When the water content of the seed is maintained at a constant level, physical imbibition is complete (Phase II, plateau phase). The protrusions of the radicle and coleoptile then break through the testa, and the growth becomes visible (Phase III; Bewley, 1997; Nambara et al., 2010; Nonogaki et al., 2010). Seed germination occurs strictly in Phases I and II, during which the seed undergoes complex physiological and biochemical changes (Rajjou et al., 2012). According to transcriptome data, dry seeds of Arabidopsis and barley contain over 12,000 transcripts, whereas those of rice contain over 17,000 transcripts (Nakabayashi et al., 2005; Howell et al., 2008; Sreenivasulu et al., 2008). Extant mRNAs stored in seeds are directly used to guide de novo protein synthesis during the early germination stage via seed imbibition and cell rehydration (Kimura and Nambara, 2010). Moreover, during germination, the damage to DNA and proteins caused by oxidative stress during the seed dehydration, storage, and rehydration stages are repaired (Cheah and Osborne, 1978; Dandoy et al., 1987; Oge et al., 2008). Subsequently, new genes are transcribed and they continue to participate in the regulation of germination (Howell et al., 2008). Glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are then activated to provide energy for seed germination, and normal metabolism is gradually restored following imbibition (Hourmant and Pradet, 1981; Howell et al., 2008).

Plant hormones, particularly abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA), are critical for the regulation of seed germination. A high ABA concentration promotes dormancy and inhibits seed germination, whereas high GA levels promote seed germination by reversing dormancy. The ratio of ABA to GA has a significant effect on the metabolic transition for seed germination (Yamaguchi, 2008; Nambara et al., 2010). Several genes regulate seed germination by regulating ABA biosynthesis or signal transduction. The enzyme 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) catalyzes 9-cis neoxanthin to xanthoxin and is involved in the biosynthesis of ABA, which regulates seed germination (Bassel et al., 2008). ABA INSENSITIVE 3 (ABI3) and ABI5, which act downstream of ABI3, have a significant effect on seed germination in ABA signaling (Lopez-Molina et al., 2001). Additionally, the level of GA is regulated by the GA biosynthesis genes, such as GA20ox3, GA3ox1, and GA2ox5, which are required for seed germination (Yamauchi et al., 2004; Iglesias-Fernandez and Matilla, 2009).

Posttranslational protein modifications (PTMs) are critical for seed germination control as they can affect the activity and stability of proteins (Rajjou et al., 2012). Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of proteins are critical regulatory mechanisms. Many phosphatases and kinases are involved in seed germination processes, including energy metabolism, DNA repair, and phytohormone signaling pathway (Hourmant and Pradet, 1981; Brock et al., 2010; Hubbard et al., 2010). Three members of the sucrose non-fermenting 1-related protein kinase 2 (SnRK2) in Arabidopsis, SnRK2.2, SnRK2.6, and SnRK2.3, play important roles in the phosphorylation of ABI5 to influence seed development and germination (Nakashima et al., 2009). Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) also play a role in regulating seed germination. MAPK11 interacts with phosphorylate SnRK1, whereas protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) promotes seed germination in tomatoes by inhibiting SnRK2.2, thus activating ABI5 and inhibiting germination (Song et al., 2021). Similarly, Arabidopsis PP2C5 promotes seed germination through direct interaction with MAPK3, MAPK4, and MAPK6, all of which are involved in ABA signaling (Brock et al., 2010). Other PTMs, such as glycosylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation, play a role in seed germination (Arc et al., 2011). Additionally, certain cell wall remodeling enzymes, such as xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase and cellulose, may play a significant role in the germination process as water uptake results in increased cellular volume and turgor pressure in dry seeds (Nonogaki et al., 2010).

Germination is a complex quantitative trait that is regulated by a large number of genetic loci and is influenced by environmental factors. Quantitative trait locus mapping and genome-wide association study (GWAS) are two critical methods in quantitative genetics that are widely used to dissect the genetic architecture of seed germination in plants (Schaar et al., 1997; Anzala et al., 2006; Ikeda et al., 2009; Landjeva et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2014). The Delay of Germination 1 (DOG1) gene is a critical regulator of seed dormancy and germination, and it was positionally cloned from Arabidopsis (Bentsink et al., 2006). DOG1 regulates seed dormancy and inhibits germination by interacting with and inhibiting the activity of two PP2Cs, AHG1 and AHG3 (Née et al., 2017). In rice, seed dormancy 4 (Sdr4) was cloned using positional cloning and acted downstream of OsVP1 to inhibit seed germination (Sugimoto et al., 2010). GWAS has also been used to dissect the genetic basis of rice (Shi et al., 2017), sorghum (Upadhyaya et al., 2016), and rape seed (Hatzig et al., 2015) germination traits. However, there are only a few studies on the genetic basis of maize seed germination (ref), and studies on maize seed germination are even more scarce.

In this study, we used 1,219,401 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and a mixed linear model (MLM) to conduct a GWAS on two seed germination traits, germination speed (GS), and germination consistency (GC), in a maize association panel comprising 321 diverse inbreds. We identified a series of significant SNPs and 36 candidate genes associated with GS and GC. These two traits partially share a genetic basis. Proper accumulation of favorable alleles may result in a reduction in germination time or an increase in germination uniformity. These results provide available resources that could be used to enhance maize seed germination.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

An association panel comprising 508 diverse maize inbred lines (Liu et al., 2017) was grown in Tieling City, Liaoning Province, China (42.5°N, 124.2°E) in May 2016. To minimize the environmental influence, seeds from 321 maize inbreds that were simultaneously pollinated were selected to evaluate seed germination phenotypes. Based on the population structure (membership probabilities ≥0.60), the 321 maize accessions were categorized into 72 tropical lines, 140 temperate lines (NSS and SS), and 109 mixed lines (Yang et al., 2011; Li et al., 2013). All seeds were dried and stored for at least 6 months to break dormancy.

Seed Germination Test and Phenotype Assessment

We used 10-cm square plastic petri plates filled with vermiculite for the germination test. Each petri plate with vermiculite was filled with 80 ml of distilled water. The seeds of each accession were sterilized for 10 min with a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution and then rinsed four times with distilled water. Subsequently, 20 seeds from each accession were placed in a petri plate filled with moist vermiculite and the embryo was kept upright to observe germination. All petri plates were placed in a phytotron set to 28°C for dark conditions with a relative humidity of 100%. When the radicles and coleoptiles reached a visible length of ≥2 mm, the seeds were considered to have germinated. Every 4 h, the number of germinated seeds was counted. The time required for 50% of seeds to germinate represents the GS. The first germination of a seed is denoted by the term first germination (FG). The formula used to calculate GC is as follows: GC = GS − FG. Using MLM, we calculated the best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) values for four independent germination experiments. For each trait, the based broad-sense heritability was calculated as , where is the genetic variance, is the residual error variance, and n represents the number of replications (Coles et al., 2010).

Genome-Wide Association Analysis

The BLUP values and 1,219,401 SNPs with a minor allele frequency of ≥0.05 in 321 lines (Liu et al., 2017) were used to conduct GWAS, which was implemented using an MLM in TASSEL V5.0 (Bradbury et al., 2007), where the population structure matrix (Q) and the relative kinship matrix (K) matrices were fitted to control spurious associations. To avoid false negatives, we used a threshold of p ≤ 1.82 × 10−5 (1/54926) for determining significant SNPs. A 54,926 is the number of independently occurring SNPs (r2 < 0.1) as determined by Plink v1.07. The R function lm () was used to determine the explained phenotypic variance of mutual SNPs in GS and GC.

Candidate Genes Annotation

The most significant SNP within an LD block comprising adjacent significant SNPs with r2 > 0.1 of each other was chosen to represent the locus associated with GC or GS. The physical locations of significant SNPs were determined using the B73 RefGen v2 database. Candidate genes were annotated using data from the maize GDB website. The Maize GDB Gene Function and Expression database were used to download raw RNA-seq and proteomics data (https://download.maizegdb.org/ GeneFunction and Expression).

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

The seeds of B73 were sterilized with 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 min, rinsed four times with distilled water, and then transferred to 9-cm plastic petri plates lined with wet filter paper in a growth chamber set to 28°C for imbibition. Embryo and endosperm were isolated from dry seeds or seeds at various stages of imbibition and stored at −80°C. The RNeasy Plant Mini kit was used to extract the RNA (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). RT-qPCR reactions were performed using an ABI7500 real-time PCR system using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (Takara). Transcript levels were analyzed using the comparative CT (2−△CT) method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). ZmTubulin1 (GRMZM2G152466) was used as an internal control for data normalization. All data were measured in three independent biological replicates. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Allele Pyramiding

Plink v1.07 was used to determine the independent significant SNPs with parameter --no-parents --no-sex --no-fid --r2 --ld-window 1 --ld-snp-list --ld-window-r2 0. If r2 between two SNPs is less than 0.1, the two SNPs are considered as independent. To avoid the effect of missing values, independent significant SNPs were further filtered with missing rate less than 10% in each maize subgroup (temperate maize or tropical maize), and the resulting SNPs were used for allele pyramiding.

Results

Characterization of Maize Seed Germination Traits

Environmental factors that occur during seed maturation can affect seed germination. To mitigate the effects of environmental heterogeneity during maturation, 321 diverse maize inbred lines harvested at similar times were used to estimate germination traits. These lines were selected from an association panel of 508 accessions that have been widely used to dissect the genetic architecture of complex traits such as oil content, drought tolerance, and flowering time (Li et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2018a).

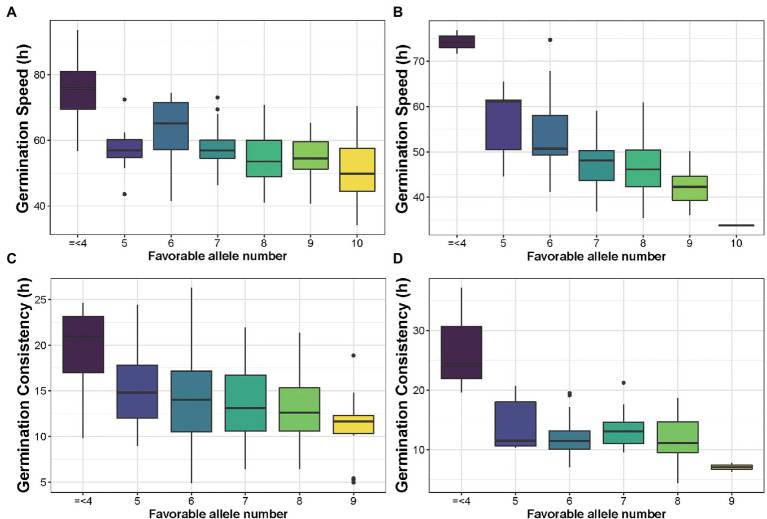

The time taken for 50% of the seeds to germinate represents seed GS, and the time interval between the first and 50% seed germination represents GC. Four independent germination experiments were conducted to determine the effect of the environment on germination. Following that, the phenotypic BLUP data from four germination tests were calculated and analyzed. Both GS and GC in our panel had a near-normal distribution (Figure 1) and a wide range of values, ranging from 33.78 to 93.67 h (mean 53.99 ± 10.19 h) for GS and 4.42 to 43.21 h (mean 13.37 ± 5.12 h) for GC (Table 1). Additionally, GS and GC had a strong positive correlation (r = 0.86; Figure 1). The broad-sense heritability (h2) was then calculated using the method of Coles et al., (2010). GS had a higher heritability (h2 = 0.75), whereas GC had a moderate heritability (h2 = 0.58; Table 1). These findings indicate that the population’s broad phenotypic variations in GS and GC are largely a result of genetic factors and thus are suitable for further association mapping.

Figure 1.

Frequency distributions and correlations of two germination traits. The plots on the diagonal show the phenotypic distribution of two traits. The plots below the diagonal line are the scatter plots compared with two traits, and the values above the diagonal line are Pearson correlation coefficient between traits. **p ≤ 0.01; GS represents the germination speed; and GC represents the germination consistence.

Table 1.

Phenotypic performance, variance component, and broad-sense heritability of germination speed (GS) and germination consistency (GC).

| Trait | Range (h) | M ± SD (h) | h2a |

|---|---|---|---|

| GS | 33.78–93.67 | 53.99 ± 10.19 | 0.75 |

| GC | 4.42–43.21 | 13.37 ± 5.12 | 0.58 |

Family mean-based broad-sense heritability.

Genome-Wide Association Analysis of GS and GC in Maize

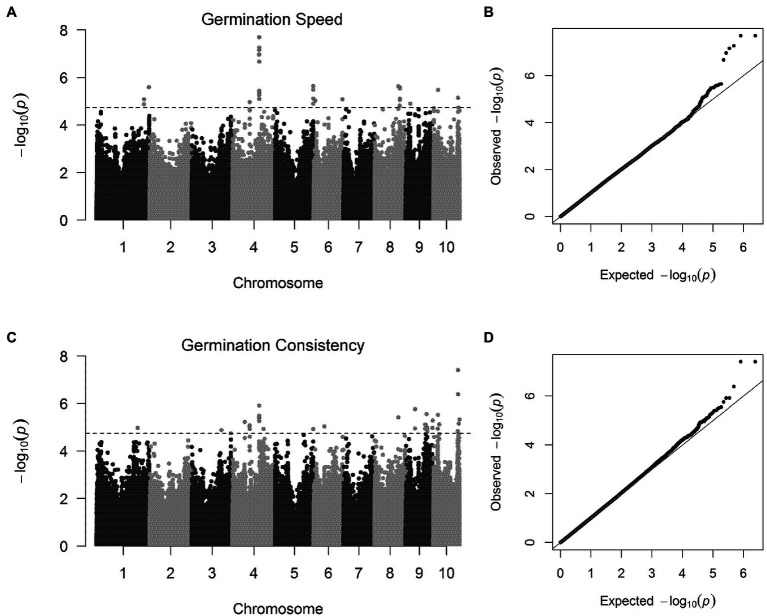

To ascertain the genetic basis of GS and GC, we conducted a GWAS on the two traits in a panel of 321 inbreds using BLUP data as the phenotype and a MLM as the genotype. A 33 significant SNPs for GS were identified on chromosomes 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10 (Figures 2A,B; Table 2). A 37 significant SNPs in nearly 10 chromosomes, except for chromosomes 2 and 7, were identified for GC (Figures 2C,D; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Genome-wide association mapping of GS and GC using MLM method. The Manhattan plots show significant p-values associated with GS and GC from a genome-wide scans plotted against the position on each of the 10 chromosomes. Genomic locations and allele effects of significant SNPs located representative genes for GS and GC. The dashed line indicates the genome-wide significance thresholds of 1.82 × 10−5. The vertical axis in quantile–quantile plots represents observed p-values and the horizontal axis indicates expected values. (A,B) are the Manhattan plot and quantile–quantile plot for GS, respectively. (C,D) are the Manhattan plot and quantile–quantile plot for GC, respectively.

Table 2.

SNP chromosomal positions and candidate genes are significantly associated with germination traits identified by GWAS.

| Trait | SNP | Chr | Position (bp) | R2 (%)a | p-value | Gene | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS | chr1.S_268251922 | 1 | 268251922 | 1.34E-05 | GRMZM5G881950 | Unknown | |

| GS | chr1.S_268736499 | 1 | 268736499 | 6.1 | 8.34E-06 | GRMZM2G137788 | Receptor protein kinase TMK1 precursor |

| GS | chr1.S_296259764 | 1 | 296259764 | 7.4 | 2.59E-06 | GRMZM2G113137 | Cellulose synthase |

| GS | chr4.S_96832829 | 4 | 96832829 | 6.3 | 1.08E-05 | GRMZM5G835747 | Unknown |

| GS | chr4.S_150576794 | 4 | 150576794 | 9.8 | 2.04E-08 | GRMZM2G163193 | FTSH protease |

| GS | chr5.S_215481320 | 5 | 215481320 | 6.7 | 3.26E-06 | GRMZM5G841101 | RNA-binding (RRM/RBD/RNP motifs) family protein |

| GS | chr5.S_21550332 | 215505332 | 1.27E-05 | GRMZM2G379002 | Unknown | ||

| GS | chr5.S_216179154 | 216179154 | 2.30E-06 | GRMZM2G155699 | AT-hook motif nuclear-localized protein | ||

| GS | chr6.S_9491447 | 6 | 9491447 | 7.6 | 9.59E-06 | GRMZM2G301884 | P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases |

| GS | chr6.S_164142777 | 6 | 164142777 | 6.2 | 8.39E-06 | GRMZM2G377615 | RHO guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor 12 |

| GS | chr8.S_133947794 | 8 | 133947794 | 12.6 | 2.39E-06 | GRMZM2G141859 | Protein phosphatase 2C |

| GS | chr8.S_141651532 | 8 | 141651532 | 1.55E-05 | GRMZM2G351990 | Unknown | |

| GS | chr8.S_143468126 | 8 | 143468126 | 7.5 | 2.65E-06 | GRMZM2G059893 | ARM repeat domain protein kinase |

| GS | chr9.S_26606351 | 9 | 26606351 | 5.8 | 1.28E-05 | GRMZM5G870176 | Cellulose synthase-like D3 |

| GS | chr10.S_26483340 | 10 | 26483340 | 7.0 | 3.33E-06 | GRMZM2G162972 | Unknown |

| GS | chr10.S_140984524 | 10 | 140984524 | 6.1 | 7.22E-06 | GRMZM2G129133 | Calcium-binding EF hand family protein |

| Totalb | |||||||

| GC | chr1.S_232744843 | 1 | 232744843 | 11.822 | 1.08E-05 | GRMZM2G167438 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase |

| GC | chr3.S_168961869 | 3 | 168961869 | 6.982 | 1.33E-05 | GRMZM5G882078 | Serine/threonine protein kinase |

| GC | chr4.S_69283020 | 4 | 69283020 | 10.93 | 6.01E-06 | GRMZM2G133941 | Unknown |

| GC | chr4.S_96832829 | 4 | 96832829 | 6.302 | 8.56E-06 | GRMZM5G835747 | Unknown |

| GC | chr4.S_150576794 | 4 | 150576794 | 9.83 | 1.22E-06 | GRMZM2G163193 | FTSH protease |

| GC | chr4.S_176501405 | 4 | 176501405 | 6.763 | 1.19E-05 | GRMZM2G091189 | Chaperonin |

| GC | chr5.S_216179154 | 5 | 216179154 | 7.258 | 1.20E-05 | GRMZM2G155699 | DNA binding protein |

| GC | chr6.S_62450201 | 6 | 62450201 | 8.075 | 9.37E-06 | GRMZM2G444845 | BAG domain containing protein |

| GC | chr8.S_96,269452 | 8 | 96269452 | 7.48 | 2.14E-06 | GRMZM5G821139 | Unknown |

| GC | chr8.S_133947794 | 8 | 133947794 | 12.618 | 3.90E-06 | GRMZM2G141859 | Protein phosphatase 2C |

| GC | chr9.S_53552857 | 9 | 53552857 | 12.633 | 1.75E-06 | GRMZM5G802679 | Unknown |

| GC | chr9.S_111117600 | 9 | 111117600 | 7.83E-06 | GRMZM2G465383 | Unknown | |

| GC | chr9.S_114102553 | 9 | 114102553 | 7.83E-06 | GRMZM2G095219 | Unknown | |

| GC | chr9.S_119304980 | 9 | 119304980 | 15.133 | 2.82E-06 | GRMZM2G098079 | Transferases transferring acyl groups |

| GC | chr9.S_123213461 | 9 | 123213461 | 6.464 | 1.08E-05 | GRMZM2G109286 | Phospholipase C |

| GC | chr9.S_124319815 | 9 | 124319815 | 6.386 | 1.50E-05 | GRMZM2G163774 | Cytochrome P450 |

| GC | chr9.S_152678737 | 9 | 152678737 | 5.957 | 1.08E-05 | GRMZM2G063387 | Transcription factor DP |

| GC | chr9.S_154644180 | 9 | 154644180 | 10.004 | 5.29E-06 | GRMZM2G109987 | Leucine zipper family protein |

| GC | chr9.S_26358058 | 10 | 26358058 | 1.15E-05 | GRMZM2G130724 | Unknown | |

| GC | chr10.S_26483340 | 10 | 26483340 | 6.955 | 3.07E-06 | GRMZM2G162972 | Unknown |

| GC | chr10.S_34368108 | 10 | 34368108 | 8.286 | 7.71E-06 | GRMZM2G119465 | Phosphatidylinositol transfer family protein |

| GC | chr10.S_138881361 | 10 | 138881361 | 6.545 | 1.48E-05 | GRMZM2G091579 | Unknown |

| GC | chr10.S_140984,524 | 10 | 140984524 | 6.145 | 3.96E-08 | GRMZM2G129133 | Calcium-binding EF hand family protein |

| GC | chr10.S_145197,460 | 10 | 145197460 | 7.894 | 7.08E-06 | GRMZM2G086030 | Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-like superfamily protein |

| GC | chr10.S_149450922 | 10 | 149450922 | 10.331 | 4.73E-06 | GRMZM5G869572 | Transportin |

| Totalb | |||||||

Percentage of phenotypic variation explained by the additive effect of the single significant SNP.

Total percentage of phenotypic variation explained by all the significant SNPs.

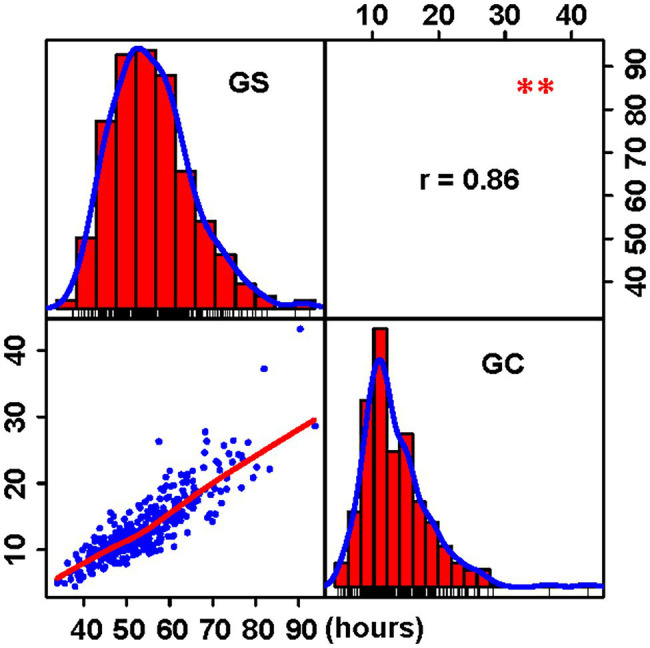

To better understand the genetic basis of GS and GC, we analyzed the significant SNPs for GS and GC. Twelve SNPs were detected in both GS and GC (Figure 3). The common SNPs account for 27.8% of GS phenotypic variation and 23.8% of GC phenotypic variation, and both of the most significant SNPs for GS (chr4.S_150576794) and GC (chr10.S_140984524) are included in the common SNPs (Table 2). These findings indicate that GS and GC in maize are controlled by multiple genetic loci and that the two germination traits have a genetic basis that is partially overlapped, which is consistent with the high correlation between GS and GC.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram showing the SNP overlap between GC and GS.

Candidate Genes Identification

A total of 58 SNPs were identified that were significantly associated with two germination traits, 46 of which are located within the gene body regions, 1 of which is located 2 kb upstream of the coding region, and the remaining 11 of which are located 300 bp–5 kb downstream of the coding genes. A total of 36 candidate genes were identified that co-localized significantly with SNPs, including 16 genes for GS, 25 genes for GC, and 6 genes for both traits. The molecular functions of the candidate genes were found to be involved in a variety of categories, including energy metabolism, signal transduction, and transcriptional regulation (Table 2).

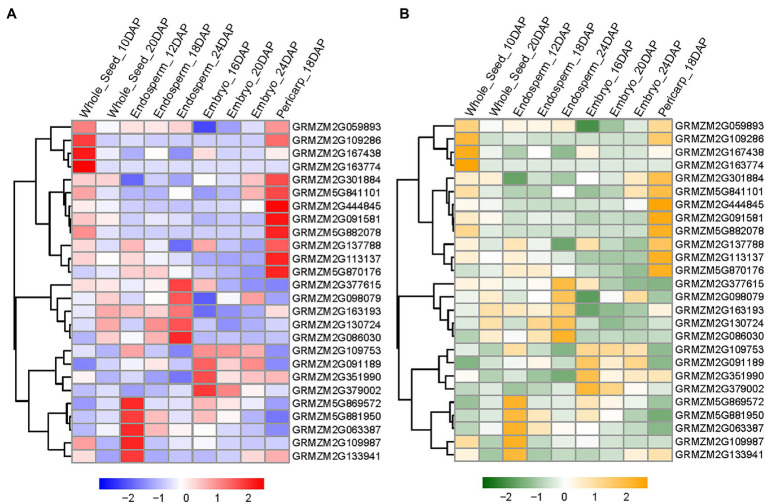

To ascertain which candidate is more likely to be responsible for the significant SNP, we performed additional analysis on their expression and protein pattern using previously published RNA-seq and proteomics data from different seed development stages (Sekhon et al., 2011; Stelpflug et al., 2016). We noted that 26 of the 36 genes are expressed during seed development (Figure 4A). Furthermore, proteins encoded by these 26 genes were accumulated during the seed development and germination stage (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Expression and protein accumulation profiles of candidate genes identified by GWAS. (A) The heat map exhibits expression patterns of candidate genes during seed development. Log2-based fold change is used to create the heat map and fold changes are shown in color. (B) The heat map exhibits protein accumulation of candidate genes during seed development. Log2-based fold change is used to create the heat map and fold changes are shown in color.

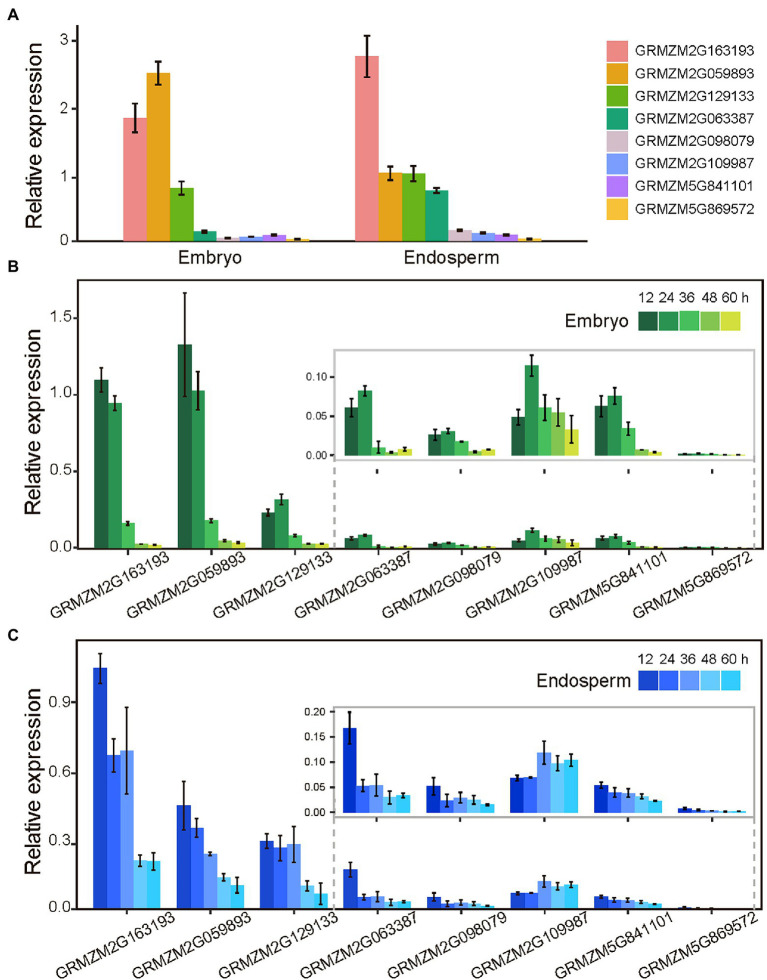

According to the functions and expression patterns of genes and the significance of SNPs, eight genes were selected for further expression pattern analysis in dry and imbibing seeds using qRT-PCR, including two candidate genes for GS (GRMZM5G841101 and GRMZM2G059893), four candidate genes for GC (GRMZM2G098079, GRMZM2G063387, GRMZM2G109987, and GRMZM5G869572), and two candidate genes for both traits (GRMZM2G163193 and GRMZM2G129133). In dry endosperm, four genes (GRMZM2G163193, GRMZM2G059893, GRMZM2G129133, and GRMZM2G063387) had significantly higher transcriptional levels than others, and three were also highly expressed in dry embryo (GRMZM2G163193, GRMZM2G059893, and GRMZM2G129133; Figure 5A). The presence of transcripts from eight genes in dry seeds indicated that they had been stored and prepared for seed germination under optimal conditions. During the seed imbibition stage, the expression patterns of eight genes were also detected. Within 24 h of imbibition, the transcriptional levels of six genes increased in the embryo and then decreased. During the imbibition stage, the expression levels of the other two genes (GRMZM2G163193 and GRMZM2G059893) continued to decline (Figure 5B). Except for GRMZM2G109987, the transcriptional levels of all genes decreased during seed imbibition (Figure 5C). The fact that the transcriptional levels of eight genes varied in response to seed imbibition time suggest that these candidate genes may be involved in seed germination processes.

Figure 5.

Expression patterns of candidate genes in dry and germination seed by qRT-PCR. (A) The expression levels of candidate genes in dry embryo and endosperm. (B) Expression levels of candidate genes in the embryo of imbibition seeds. (C) Expression levels of candidate genes in the endosperm of imbibition seeds. Vertical bars indicate standard deviation.

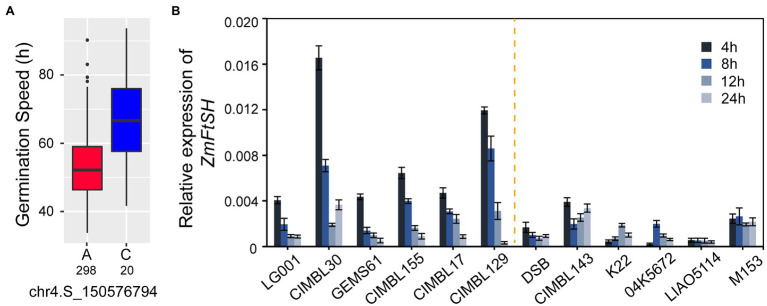

GRMZM2G163193 contained the most significant SNPs of GC and GS (Figure 6A) and encoded the filamentation temperature sensitive H (FtsH) protease; accordingly, it was labeled as ZmFtsH. To further analyze the expression patterns of ZmFtsH between different genotypes, 12 inbreed lines were randomly selected from 321 lines based on the genotype of the gene’s most significant SNP. LG001, GEMS61, CIMBL30, CIMBL143, DSB, and K22 are all A allele genotypes for SNP chr4.S_150,576,794 that require less time for germination at the population level (SNP within ZmFtsH). In lines carrying the A allele genotype at SNP (chr4.S_150,576,794), the relative expression of ZmFtsH was higher during the initial stage of imbibition (4 h) but significantly decreased with a time extension. In contrast, the relative expression of ZmFtsH was lower in lines carrying the C genotype, and it remained relatively stable or increased gradually over time (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Allele effect of SNP and expression patterns of ZmFtsH during seed germination. (A) Allele effect of SNP chr4.S_150576794 for GS, 298 and 20 are represent the number of A and C genotype in population, respectively. (B) The relative expression level of ZmFtsH at seeds imbibition 4, 8, 12, 24 h by qRT-PCR in 12 lines, including LG001, CIMBL30, GEMS61, CIMBL155, CIMBL17, and CIMBL129, containing A allele; DSB, CIMBL143, K22, 04 K5672, LIA5114, and M153, containing C allele. Vertical bars indicate standard deviation.

Alleles Pyramiding and Molecular Breeding Application

The allele effect of each independent significant SNP was investigated and shown in Supplementary Figure S1. GS values varied between alleles from 1.8 to 13.3 h. The SNP chr4.S_150,576,794 is the most significant locus (value of p = 2.04E-08, MLM) for GS, with the mean value of two alleles being 53.2 h (A allele) and 66.5 h (C allele; Figure 6A; Supplementary Figure S1). We also examined the allele effects of significant SNPs in GC and discovered that the effects between alleles of significant SNPs are significant (Supplementary Figure S2).

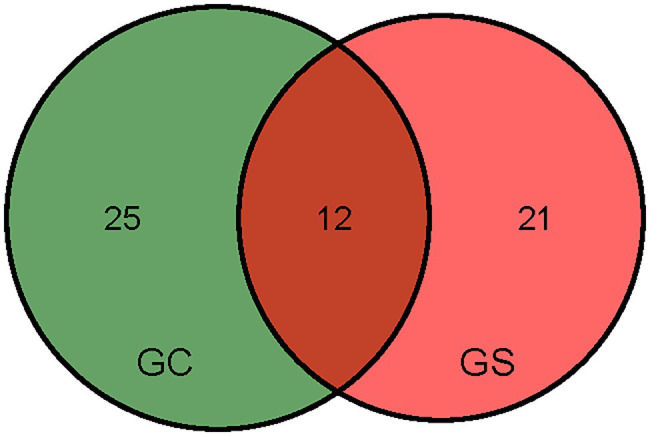

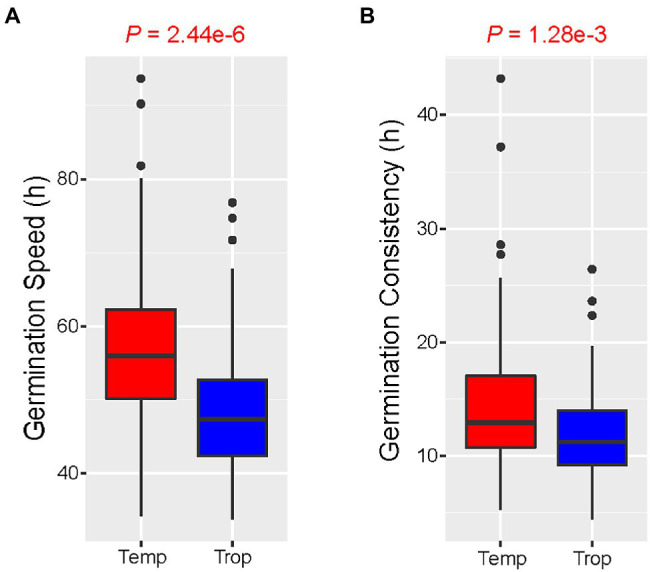

The 321 accessions used in this study were categorized into three subpopulations based on their population structure: temperate, tropical, and mixed. The favorable alleles are those that affect rapid or uniform germination. To demonstrate that favorable alleles can improve germination traits, allele pyramiding was used to determine the efficacy by increasing the number of favorable alleles. To avoid the effect of missing values, we used for further analysis only independent significant SNPs with a missing rate of less than 10% in each subgroup. As a result of the analysis, 10 SNPs were retained for GS and 9 for GC. With the accumulation of favorable alleles from GS, seed germination was observed to be faster, particularly in tropical populations. When the number of favorable alleles reached seven, GS gradually decreased in the temperate population (Figure 7A). In contrast, GS continued to decline as favorable alleles accumulated in the tropical populations (Figure 7B). Similar to the GS, seed germination became more uniform as the number of favorable alleles increased, particularly in tropical populations. When accessions carried more than five favorable alleles, germination uniformity was gradually increased in both temperate and tropical populations (Figures 7C,D). Furthermore, tropical lines germinate more rapidly and uniformly than temperate lines (Figures 8A,B). These results indicate that seed germination traits could be enhanced through molecular breeding by polymerizing these favorable alleles for cultivation requirements.

Figure 7.

Boxplot of favorable alleles pyramiding for GS and GC in two germination traits. (A) Analysis of favorable alleles pyramiding for GS in the temperate subpopulation. (B) Analysis of favorable alleles pyramiding for GS in the tropical subpopulations. (C) Analysis of favorable alleles pyramiding for GC in the temperate subpopulation. (D) Analysis of favorable alleles pyramiding for GC in the tropical subpopulations.

Figure 8.

Boxplot of germination traits in a different subpopulation. (A) Analysis of variance to examine the difference in germination speeds between temperate and tropical subpopulations. (B) Analysis of variance to examine the differences in germination consistency between temperate and tropical subpopulations.

Discussion

Seed germination is a very important trait in crop production. In previous studies, many indirect germination traits, such as germination percentage and seedling growth in germination Phase III, were used to evaluate the seed germination (Ji et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). However, seed germination Phases I and II are physiologically distinct from Phase III and are likely regulated by distinct regulatory pathways (Holdsworth et al., 2008). GS quantified the rate of germination and GC measured the uniformity of germination. Both traits provided an indirect insight into seed germination status during Phases I and II. Additionally, the rate and uniformity of germination were influenced by seed dormancy and environmental conditions during seed production. To reduce the noise in the germination tests, we used 321 maize accessions that had matured under similar environmental conditions to measure two seed germination-related traits (GS and GC) under -common germination conditions. Furthermore, all seeds used in the germination test had been dried and stored to break the dormancy. ermination phenotypes were counted every 4 h to increase accuracy.

Two germination traits exhibited a high degree of phenotypic variations, and the data showed normal distribution. Germination traits are complex and environment-dependent. The heritability (h2) was calculated to determine the number of genetic factors that contribute to phenotypic variation. The high h2 observed in GS and GC indicated that hereditary factors were the primary determinant of GS and consistency. A significant positive correlation was observed between GS and GC suggests that GS and uniformity were coordinated at population levels. On chromosomes 4, 5, 8, and 10, 12 common SNPs for GS and GC were identified, including the most significant chr4.S_150576794 for GS and the chr10.S_140984524 for GC (Figure 3). Two germination traits seem to be partially controlled by the same genetic factors.

Energy metabolism provides the energy required for seed germination. After several hours of imbibition, respiration is required to provide ATP via the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria (Hourmant and Pradet, 1981). Two FtsH proteins located in mitochondria have been shown to regulate the growth of Arabidopsis by influencing the activity of complexes involved in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (Piechota et al., 2010). In this study, ZmFtsH (GRMZM2G163193) encoded an FtsH protein that was stored in dry seeds and expressed during seed germination. In the initial imbibition stage of 4 h, ZmFtsH expression was increased in SNP (chr4.S_150576794) A allele genotype lines (shorter germination time at population levels). The high expression of ZmFtsH contributes to energy mobilization and thus the seed germination in A allele genotype lines. The differential expression of ZmFtsH implies that the rate at which energy is mobilized may have important effects on germination traits in the natural population. PP2C played a role in and positively regulated seed germination (Brock et al., 2010). GRMZM2G141859 in SNP (chr8.S_133947794) encoded a PP2C-type gene that may be involved in the ABA signaling pathway that regulates seed germination. In a sense, seeds are stressed and cells are damaged during the maturation and drying processes. Certain signaling factors are activated, resulting in the production of protective proteins (Grelet et al., 2005; Tolleter et al., 2007). Calmodulin-like proteins (CMLs) function as the second massager in stress responses (Gao et al., 2004; Jiang et al., 2013). GRMZM2G129133 encoded a CML protein, which is expressed during seed maturation and germination.

PTMs of proteins affect their stability, activity, and function. Proteins that were damaged and lost function during maturation, death, and imbibition were repaired by PTMs. A series of protein kinases and phosphatases involved in the regulation of proteins phosphorylation and dephosphorylation have been implicated in seed germination regulation (Brock et al., 2010; Hubbard et al., 2010). It has been proposed that phosphorylation is involved in DNA repair during seed germination (Lu et al., 2008). In this study, four genes related to phosphorylation and dephosphorylation were identified, including three protein kinase genes (GRMZM2G137788, GRMZM2G059893, and GRMZM5G882078) and one phosphatase gene (GRMZM2G141859). Additionally, an acyltransferase gene (GRMZM2G098079) was identified as a candidate gene for seed germination. Gene expression is regulated on multiple levels by regulatory factors during germination, for example, RNA transcription initiation and RNA processing (Lee et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2018b). We identified a transcription factor (GRMZM2G063387) and an RNA-binding protein (GRMZM5G841101) as potential regulators for germination.

Germination traits vary among maize subpopulations at the population level, and seed germination takes less time in tropical accessions than in temperate accessions. We analyzed alleles from different subpopulations and found that favorable alleles accumulated in GS and GC had a greater effect on the tropical subpopulation than on the temperate subpopulation. Seed germination is different from seed dormancy. When seed dormancy is broken, tropical accessions germinate more rapidly than temperate accessions. Seed must likely germinate immediately under suitable conditions to avoid the invasion of bacteria and viruses in tropical regions with high temperatures and humidity. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the tropical germplasm resources for seed germination. GC of tropical subpopulations is also better than temperate subpopulations but not as significantly as GS, which may be due to shorter germination times in tropical subpopulations demonstrating more uniform germination than temperate subpopulations. This finding implies that the differences in GC between two subpopulations may be due to factors other than genetics.

In conclusion, the germination traits of maize seeds were critical for production. During the breeding process, traits such as rapid and uniform germination that are suitable for human needs are selected. Almost all significant SNPs in our study showed distinct phenotypes between alleles. With an increase in the number of favorable alleles (except for very much or very little), germination became more rapid and uniform (Figure 7). GWAS was used to dissect the seed germination traits in the 321 maize inbred lines. Furthermore, 58 significant SNPs were identified, reflecting the complexity of maize seed germination. Several candidate genes that were associated with significant SNPs were identified, and one of them, the energy metabolism-related gene ZmFtsH (GRMZM2G163193), may be more important for seed germination in maize. These results suggested that using SNPs derived from natural variation as markers will be beneficial for future molecular breeding of maize seed germination.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

CL and YaL: conceptualization and methodology. YuL, QZ, JY, ML, and ZW: data collection. YaL and ML: formal analysis. CL: funding acquisition. JF and YR: investigation. CL and AZ: supervision. YaL and XD: visualization. YuL, CL, and YaL: writing—original draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China (no. 31601233) and National Foreign Experts Program of China (no. DL2021006002L).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Feng Tian (National Maize Improvement Center, China Agricultural University) for valuable suggestions and technical supports. We thank Xiaohong Yang (National Maize Improvement Center, China Agricultural University) for providing the maize association panel.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.930438/full#supplementary-material

References

- Anzala F., Birolleau-Touchard C., Giauffret C., Limami A. M. (2006). QTL mapping and genetic analysis of inhibitory effect of lysine on post-germination growth and seedling establishment of maize. Acta Agrono. Hungarica 54, 271–279. doi: 10.1556/AAgr.54.2006.3.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arc E., Galland M., Cueff G., Godin B., Lounifi I., Job D., et al. (2011). Reboot the system thanks to protein post-translational modifications and proteome diversity: how quescent seeds restart their metabolism to prepare seedling establishment. Proteomics 11, 1606–1618. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000641, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Seed Analysis (1983). Seed vigour testing handbook. Contribution no. 32 to the Handbook on Seed Testing. 93.

- Bassel G. W., Fung P., Chow T. F., Foong J. A., Provart N. J., Cutler S. R. (2008). Elucidating the germination transcriptional program using small molecules. Plant Physiol. 147, 143–155. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.110841, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentsink L., Jowett J., Hanhart C. J., Koornneef M. (2006). Cloning of DOG1, a quantitative trait locus controlling seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 17042–17047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607877103, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley J. D. (1997). Seed germination and dormancy. Plant Cell 9, 1055–1066. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1055, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury P. J., Zhang Z., Kroon D. E., Casstevens T. M., Buckler E. S. (2007). Tassel: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23, 2633–2635. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock A. K., Willmann R., Kolb D., Grefen L., Lajunen H. M., Bethke G., et al. (2010). The Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase PP2C5 affects seed germination, stomatal aperture, and abscisic acid-inducible gene expression. Plant Physiol. 153, 1098–1111. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156109, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah K. S., Osborne D. J. (1978). DNA lesions occur with loss of viability in embryos of ageing rye seed. Nature 272, 593–599. doi: 10.1038/272593a0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles N. D., McMullen M. D., Balint-Kurti P. J., Pratt R. C., Holland J. B. (2010). Genetic control of photoperiod sensitivity in maize revealed by joint multiple population analysis. Genetics 184, 799–812. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.110304, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandoy E., Schnys R., Deltour R., Verly W. G. (1987). Appearance and repair of apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in DNA during early germination of Zea mays. Mut. Res. Fund. Mol. Mechan. Mutagene. 181, 57–60. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(87)90287-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R. H. (1992). Seed and seedling vigour in relation to crop growth and yield. Plant Growth Regul. 11, 249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00024563 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D., Knight M. R., Trewavas A. J., Sattelmacher B., Plieth C. (2004). Self-reporting Arabidopsis expressing pH and [Ca2+] indicators unveil ion dynamics in the cytoplasm and in the Apoplast under abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 134, 898–908. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032508, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelet J., Benamar A., Teyssier E., Avelangemacherel M., Grunwald D., Macherel D. (2005). Identification in pea seed mitochondria of a late-embryogenesis abundant protein able to protect enzymes from drying. Plant Physiol. 137, 157–167. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.052480, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G., Liu X., Sun F., Cao J., Huo N., Wuda B., et al. (2018a). Wheat mir9678 affects seed germination by generating phased sirnas and modulating abscisic acid/gibberellin signaling. Plant Cell 30, 796–814. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00842, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Wang X., Zhao M., Huang C., Li C., Li D., et al. (2018b). Stepwise cis-regulatory changes in ZCN8 contribute to maize flowering-time adaptation. Curr. Biol. 28, 3005.e4–3015.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.029, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzig S. V., Frisch M., Breuer F., Nesi N., Snowdon R. J. (2015). Genome-wide association mapping unravels the genetic control of seed germination and vigor in brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 6:221. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth M. J., Bentsink L., Soppe W. J. J. (2008). Molecular networks regulating Arabidopsis seed maturation, after-ripening, dormancy and germination. New Phytol. 179, 33–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02437.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourmant A., Pradet A. (1981). Oxidative phosphorylation in germinating lettuce seeds (Lactuca sativa) during the first hours of imbibition. Plant Physiol. 68, 631–635. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.3.631, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell K. A., Narsai R., Carroll A. J., Ivanova A., Lohse M., Usadel B., et al. (2008). Mapping metabolic and transcript temporal switches during germination in Rice highlights specific transcription factors and the role of RNA instability in the germination process. Plant Physiol. 149, 961–980. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.129874, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard K. E., Nishimura N., Hitomi K., Getzoff E. D., Schroeder J. I. (2010). Early abscisic acid signal transduction mechanisms: newly discovered components and newly emerging questions. Genes Dev. 24, 1695–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.1953910, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Fernandez R., Matilla A. (2009). After-ripening alters the gene expression pattern of oxidases involved in the ethylene and gibberellin pathways during early imbibition of Sisymbrium officinale L. seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 1645–1661. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp029, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T., Ohnishi S., Senda M., Miyoshi T., Ishimoto M., Kitamura K., et al. (2009). A novel major quantitative trait locus controlling seed development at low temperature in soybean (glycine max). Theor. Appl. Genet. 118, 1477–1488. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-0996-3, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S. L., Jiang L., Wang Y. H., Zhang W. W., Liu X., Liu S. J., et al. (2009). Quantitative trait loci mapping and stability for low temperature germination ability of rice. Plant Breed. 128, 387–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01533.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Lee J., Jin Y. M., Qiao Y., Piao R., Jang S. M., et al. (2011). Identification of QTLs for seed germination capability after various storage periods using two RIL populations in rice. Mol. Cell 31, 385–392. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0049-z, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Zhu S., Ye R., Xue Y., Chen A., An L., et al. (2013). Relationship between NaCl- and H2O2-induced cytosolic Ca2+ increases in response to stress in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 8:e76130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076130, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M., Nambara E. (2010). Stored and neosynthesized mrna in arabidopsis seeds: effects of cycloheximide and controlled deterioration treatment on the resumption of transcription during imbibition. Plant Mol. Biol. 73, 119–129. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9603-x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landjeva S., Lohwasser U., Borner A. (2010). Genetic mapping within the wheat d genome reveals QTL for germination, seed vigour and longevity, and early seedling growth. Euphytica 171, 129–143. doi: 10.1007/s10681-009-0016-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen S. U., Povlsen F. V., Eriksen E. N., Pedersen H. C. (1998). The influence of seed vigour on field performance and the evaluation of the applicability of the controlled deterioration vigour test in oil seed rape (Brassica napus) and pea (Pisum sativum). Seed Sci. Technol. 26, 627–641. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Lee H. G., Yoon S., Kim H. U., Seo P. J. (2015). The Arabidopsis MYB96 transcription factor is a positive regulator of ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE4 in the control of seed germination. Plant Physiol. 168, 677–689. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00162, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Peng Z., Yang X., Wang W., Fu J., Wang J., et al. (2013). Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of oil biosynthesis in maize kernels. Nat. Genet. 45, 43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2484, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. J., Luo X., Niu L. Y., Xiao Y. J., Chen L., Liu J., et al. (2017). Distant eQTLs and non-coding sequences play critical roles in regulating gene expression and quantitative trait variation in maize. Mol. Plant 10, 414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.06.016, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Wang X., Wang H., Xin H., Yang X., Yan J., et al. (2013). Genome-wide analysis of ZmDREB genes and their association with natural variation in drought tolerance at seedling stage of Zea mays L. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003790, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L., Mongrand S., Chua N. H. (2001). A postgermination developmental arrest checkpoint is mediated by abscisic acid and requires the ABI5 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 4782–4787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081594298, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T. C., Meng L. B., Yang C. P., Liu G. F., Liu G. J., Wang M. B. C. (2008). A shotgun phosphoproteomics analysis of embryos in germinated maize seeds. Planta 228, 1029–1041. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0805-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi K., Okamoto M., Koshiba T., Kamiya Y., Nambara E. (2005). Genome-wide profiling of stored mrna in arabidopsis thaliana seed germination: epigenetic and genetic regulation of transcription in seed. Plant J. 41, 697–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02337.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K., Fujita Y., Kanamori N., Katagiri T., Umezawa T., Kidokoro S., et al. (2009). Three arabidopsis snrk2 protein kinases, srk2d/snrk2.2, srk2e/snrk2.6/ost1 and srk2i/snrk2.3, involved in aba signaling are essential for the control of seed development and dormancy. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 1345–1363. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp083, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambara E., Okamoto M., Tatematsu K., Yano R., Seo M., Kamiya Y. (2010). Abscisic acid and the control of seed dormancy and germination. Seed Sci. Res. 20, 55–67. doi: 10.1017/S0960258510000012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Née G., Kramer K., Nakabayashi K., Yuan B., Xiang Y., Miatton E., et al. (2017). DELAY OF GERMINATION1 requires PP2C phosphatases of the ABA signalling pathway to control seed dormancy. Nat. Commun. 8:72. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00113-6, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonogaki H., Bassel G. W., Bewley J. D. (2010). Germination-still a mystery. Plant Sci. 179, 574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oge L., Bourdais G., Bove J., Collet B., Godin B., Granier F., et al. (2008). Protein repair l-Isoaspartyl Methyltransferase1 is involved in Both seed longevity and germination vigor in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 3022–3037. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058479, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry D. A. (1978). Problem soft he development and application of vigour tests to vegetable seeds. Acta Hortic. 83, 141–146. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.1978.83.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piechota J., Kolodziejczak M., Juszczak I., Sakamoto W., Janska H. (2010). Identification and characterization of high molecular weight complexes formed by matrix AAA proteases and prohibitins in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12512–12521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063644, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajjou L., Duval M., Gallardo K., Catusse J., Bally J., Job C., et al. (2012). Seed germination and vigor. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 507–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar W. V. D., Alonso-Blanco C., Leonkloosterziel K. M., Jansen R. C., Van Ooijen J. W., Koornneef M. (1997). QTL analysis of seed dormancy in Arabidopsis using recombinant inbred lines and MQM mapping. Heredity 79, 190–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6881880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon R. S., Lin H., Childs K. L., Hansey C. N., Buell C. R., de Leon N., et al. (2011). Genome-wide atlas of transcription during maize development. Plant J. 66, 553–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04527.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Gao L., Wu Z., Zhang X., Wang M., Zhang C., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association study of salt tolerance at the seed germination stage in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 17:92. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1044-0, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Shang L., Wang X., Xing Y., Xu W., Zhang Y., et al. (2021). Mapk11 regulates seed germination and aba signaling in tomato by phosphorylating SnRKs. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 1677–1690. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa564, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenivasulu N., Usadel B., Winter A., Radchuk V., Scholz U., Stein N., et al. (2008). Barley grain maturation and germination: metabolic pathway and regulatory network commonalities and differences highlighted by new MapMan/PageMan profiling tools. Plant Physiol. 146, 1738–1758. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111781, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelpflug S. C., Sekhon R. S., Vaillancourt B., Hirsch C. N., Buell C. R., de Leon N., et al. (2016). An expanded maize gene expression atlas based on RNA sequencing and its use to explore root development. Plant Genome 9, 1–16. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2015.04.0025, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K., Takeuchi Y., Ebana K., Miyao A., Yano M. (2010). Molecular cloning of sdr4, a regulator involved in seed dormancy and domestication of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 5792–5797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911965107, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekrony D. M., Egli D. B. (1991). Relationship of seed vigor to crop yield: a review. Crop Sci. 31, 816–822. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100030054x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolleter D., Jaquinod M., Mangavel C., Passirani C., Saulnier P., Manon S., et al. (2007). Structure and function of a mitochondrial late embryogenesis abundant protein are revealed by desiccation. Plant Cell 19, 1580–1589. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050104, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya H. D., Wang Y. H., Sastry D. V., Dwivedi S. L., Prasad P. V., Burrell A. M., et al. (2016). Association mapping of germinability and seedling vigor in sorghum under controlled low-temperature conditions. Genome 59, 137–145. doi: 10.1139/gen-2015-0122, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. F., Wang J. F., Bao Y. M., Wang F. H., Zhang H. S. (2010). Quantitative trait loci analysis for rice seed vigor during the germination stage. J. Zhejiang Univ.-sci. B 11, 958–964. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1000238, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Tan Z., Zhou Y., Xu R., Feng L., Xing Y., et al. (2014). Identification and fine mapping of quantitative trait loci for seed vigor in germination and seedling establishment in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56, 749–759. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12190, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S. (2008). Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 225–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Y., Ogawa M., Kuwahara A., Hanada A., Kamiya Y., Yamaguchi S. (2004). Activation of gibberellin biosynthesis and response pathways by low temperature during imbibition of Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Plant Cell 16, 367–378. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018143, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Gao S., Xu S., Zhang Z., Prasanna B. M., Li L., et al. (2011). Characterization of a global germplasm collection and its potential utilization for analysis of complex quantitative traits in maize. Mol. Breed. 28, 511–526. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9500-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.