Abstract

Background:

The most commonly used diagnostic tests for evaluation of the dental fear and anxiety (DFA) presence in children were psychometric scales, where interpretation in determining and using of their cut-off scores sometimes was not completely exact. Also, several studies have been conducted where the results were conflicting in terms of who better assessed the DFA presence - the children, their parents, or dentists.

Objective:

To determine the normative values in the child and parental versions of the Modified version of the CFSS-DS scale (CFSS-DS-mod scale) and to compare the ways in which children, their parents, and the dentist assessed the DFA presence in the dental office.

Methods:

Survey sample consisted of 200 children aged from 9 to 12 years, whose DFA presence was determined by the CFSS-DS-mod scale. Child parents answered to their version of this scale, and the dentist observed the child behavior in the dental office during the treatment using Venham Anxiety and Behaviour Rating Scales.

Results:

Parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale found to be reliable (Cronbach alpha = 0.955) and valid (67.87% of variance explained) instrument for assessment of the DFA presence in children. Two cut-off scores were determined in a child (37 and 43), as well as in a parental version of CFSS-DS-mod scale (36 and 44), respectively. Dentists assessed the DFA presence in child patients most accurately.

Conclusion:

The normative values of psychometric instruments should be considered prior to their use. The borderline area of DFA presence should also be taken into account in the future studies. Children could underestimate DFA existence by themselves while interviewing.

Keywords: dental fear and anxiety, children, CFSS-DS-mod scale, normative values, types of informant

1. BACKGROUND

Dental fear and anxiety (DFA) is a widespread clinical phenomenon in the dental office that affects the treatment plan and its implementation. DFA presence in children can be evaluated in numerous ways. The most commonly used diagnostic tests were psychometric scales, with the Dental Subscale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule (CFSS-DS scale) being used most frequently. To date, many authors have used the original version of this scale and its modified forms, in order to measure the DFA presence in children (1).

Recently, a Modified version of the CFSS-DS scale, the CFSS-DS-mod scale, was reported. It was used in children in clinical setting study in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This scale consisted of 17 items and covered topics related to dental team and dental treatment and DFA presence in the dental office. The responses were ranged by a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with a total score ranging from 17 to 85. The results of this study showed that the CFSS-DS-mod scale was a reliable and valid psychometric instrument which measured the two-dimensional nature of DFA presence in children aged 9 to 12 years in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1).

Apart from reliability and validity, one of the important features of any diagnostic test was the determination of its cut-off value as a refference point for the tested population to be divided into those who had or did not have the phenomenon observed. This cut-off value was also called cut-off score within the range of psychometric scales (2). Interpretation in determining the cut-off score sometimes was not completely exact, because of the participants who were in the borderline between the presence and the absence of the tested phenomenon. Therefore, for the purpose of clinical research of DFA presence, the identification of two cut-off scores was recently introduced, dividing the study population into three parts: those without DFA presence, those with results between two cut-off scores with subclinical manifestations of DFA presence (which have the risk of developing DFA expression), and those with DFA presence (3). So far, in studies on the measurement of DFA presence in children the cut-off scores of scales used had not always initially been identified in the tested samples. Instead, the previously determined cut-off values published in original studies have been just accepted and furtherly used. Also, studies with children have rarely considered a population with subclinical manifestations of the DFA presence so far (4).

Furthermore, DFA presence had different expression regarding the psychological maturity of patients, especially in children. That is why the quality of assessment of DFA presence, especially in this population, was therefore complicated. Generally, there were indirect (the informant was dentist or other qualified person) and direct way (the informant was child, or parents on their behalf) in which measuring of DFA presence was applied (5).

To date, several studies have been conducted using direct and indirect kind of assessment of the DFA presence in children. The results were conflicting in terms of who better assessed the DFA presence – the children, their parents, or dentists. Also, in certain number of studies with subjects younger than 8 years, the findings of parental versions of psychometric scales were identified with child versions of these scales, even using the same cut-off scores (6).

2. OBJECTIVE

Based on the aforementioned, the objectives of this study were to determine the cut-off scores and other normative values on the child and parental versions of the CFSS-DS-mod scale and to compare the ways how children, their parents, and the dentist assessed the DFA presence in the dental office.

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sample collection and ethical considerations

This research was a observational, clinical-epidemiologic controlled study, conducted within the scope of Declaration of Helsinki (7), and after the approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry with Clinics of the University of Sarajevo.

The sample consisted of a total of 200 child participants, according to the sample size calculation, in order to meet the research objectives. Study participants were mentally and physically healthy randomly selected patients aged from 9 to 12 years, who visited the Clinic / Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry of the Faculty of Dentistry with Clinics of University of Sarajevo due to previously planned dental treatment. The children with general psychological or psychiatric problems, as well as the patients with current symptoms and signs of acute odontalgia or any other emergency in dentistry (bleeding, swelling, dental trauma), were not included in the study. For the purpose of avoiding of this selection bias, pretreatment history and clinical examination was taken. The age group of 9 to 12 years old children was chosen because of its homogeneity in terms of their cognitive development, ways of perceiving, expressing and coping with DFA presence (5).

In order to avoid treatment bias, it was important to note that all study participants were made aware of planned dental treatment prior to the study dental visit. All actions and interventions in all study subjects, either before or during the planned visit, were performed under the same conditions and in the same dental office for the whole period of duration of the study.

The purpose of the study was explained both to the child participants and their parents, and the parents signed written consent for their and participation of their children in the study, given the fact that the study participants were minors. Also, the assent of the child participants was obtained in addition.

Study design – normative values and types of informant

In order to meet normative values research criteria, study sample was divided in two groups of participants. First group consisted of 100 participants who underwent preventive interventions, as non-invasive kind of dental treatments. Second group consisted of another 100 participants, where invasive dental treatments on permanent teeth, such as treatment of dental caries or tooth extraction, were performed. In cases where pain control managment was necessary in order to avoid treatment bias, local anesthesia was applied to complete the treatment.

Subjects from both study groups, as direct informant types, answered questions from the CFSS-DS-mod scale right before the planned treatment (1). The parents also completed the parental scale version, independently from the children, by providing their answers to the same questions on the CFSS-DS-mod scale on behalf of their children. It was noted whether the parental version of the scale was answered by the participant’s father or mother. The child and parental versions of fulfilled questionnaires were collected immediately afterwards, just before the scheduled dental treatment started. In order to avoid any bias in the meaning of the parental scale version items, they were translated into English language by a licensed translator, and back-translated into Bosnian language for the purpose of this publication.

In order to evaluate indirect measuring of DFA presence, the behaviours of both study groups participants were assessed in the dental office by the previously calibrated observer–trained dentist. Behavioral assessment was performed using the Venham Anxiety and Behavior Rating Scales, which showed high level of inter-rater reliability and discrimant validity (8, 9). Both scales consisted of six behaviorally defined categories in range from 0 to 5, with total score value of 10. The cut-off score value of 5 defined positive versus negative dental behaviors. Higher scores indicated higher levels of DFA presence or lack of cooperativeness. The most negative behaviors during dental treatment were observed and notified, either at the beginning, during or at the end of treatment, and then recorded on both scales, in a way that each participant was assigned two scores–one for assessing DFA presence and the other for assessing behavior during treatment. The final score value was summarized afterwards.

Statistical analysis

The data collected in this survey were statistically analyzed and presented as follows: the normative values of parental and child version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale were determined with internal consistency reliability, construct validity and cut-off scores; the normative values of Venham scales were performed by calculating of intraclass correlation coefficient with cross-tabulation method; the distribution of the obtained study results was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; the existence of statistically significant correlations was determined using Spearman’s correlation coefficient; the existence of statistically significant differences was determined using the Wilcoxon signed rank test; the inter-rater agreements were determined using Cohen’s coefficient. The statistical analysis was performed with IBM Statistical Package for Social Science software (version 23.0) for the Windows operative system and a significance level was set at 0.05.

4. RESULTS

Normative values of the CFSS-DS-mod scale

Table 1 shows the internal consistency reliability of the parental version of CFSS-DS-mod scale presented by Cronbach’s coefficient α, alltogether with corrected item-total correlation values.

Table 1. Normative values of the parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale.

| Internal consistency reliability of the parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale | ||||

| items: | Cronbach α=0.955 | corrected values of item-total correlations | ||

| 1. Is your child afraid of being in the waiting room before entering the dental office? | 0.756 | |||

| 2. Is your child afraid of being in the dental office? | 0.773 | |||

| 3. Is your child afraid of the dentist? | 0.775 | |||

| 4. Is your child afraid of people in white uniforms? | 0.588 | |||

| 5. Is your child afraid of sitting in the dental chair? | 0.838 | |||

| 6. Is your child afraid when the dentist examines his/her mouth with dental instruments? | 0.730 | |||

| 7. Is your child afraid when he/she keeps his/her mouth open? | 0.771 | |||

| 8. Is your child afraid of the suction device in his/her mouth? | 0.680 | |||

| 9. Is your child afraid when the dentist cleans his/her teeth from dental plaque? | 0.713 | |||

| 10. Is your child afraid when his/her teeth are being drilled? | 0.797 | |||

| 11. Is your child afraid of the sound of dental drilling devices? | 0.821 | |||

| 12. Is your child afraid of the sight of dental drilling devices? | 0.764 | |||

| 13. Is your child afraid of dental syringe? | 0.737 | |||

| 14. Is your child afraid of dental syringe needle? | 0.766 | |||

| 15. Is your child afraid of tooth extraction? | 0.669 | |||

| 16. Is your child afraid of dental treatment that causes pain? | 0.782 | |||

| 17. Is your child afraid when he/she is unable to breathe during dental treatment? | 0.547 | |||

| Rotated factor matrix for the parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale | ||||

| items: | KMO = 0.934 | Bartlett p<0.0005 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

| 5. Is your child afraid of sitting in the dental chair? | 0.837 | 0.346 | ||

| 7. Is your child afraid when he/she keeps his/her mouth open? | 0.819 | 0.273 | ||

| 2. Is your child afraid of being in the dental office? | 0.780 | 0.322 | ||

| 3. Is your child afraid of the dentist? | 0.761 | 0.347 | ||

| 6. Is your child afraid when the dentist examines his/her mouth with dental instruments? | 0.744 | 0.303 | ||

| 1. Is your child afraid of being in the waiting room before entering the dental office? | 0.721 | 0.365 | ||

| 8. Is your child afraid of the suction device in his/her mouth? | 0.710 | 0.270 | ||

| 9. Is your child afraid when the dentist cleans his/her teeth from dental plaque? | 0.688 | 0.348 | ||

| 4. Is your child afraid of people in white uniforms? | 0.687 | 0.154 | ||

| 11. Is your child afraid of the sound of dental drilling devices? | 0.652 | 0.546 | ||

| 10. Is your child afraid when his/her teeth are being drilled? | 0.635 | 0.533 | ||

| 17. Is your child afraid when he/she is unable to breathe during dental treatment? | 0.510 | 0.306 | ||

| 14. Is your child afraid of dental syringe needle? | 0.297 | 0.886 | ||

| 13. Is your child afraid of dental syringe? | 0.284 | 0.865 | ||

| 15. Is your child afraid of tooth extraction? | 0.251 | 0.807 | ||

| 16. Is your child afraid of dental treatment that causes pain? | 0.409 | 0.775 | ||

| 12. Is your child afraid of the sight of dental drilling devices? | 0.543 | 0.596 | ||

| % Variance | 40.370 | 27.500 | ||

| % Cumulative | 40.370 | 67.870 | ||

| Eigen value | 10.162 | 1.376 | ||

The construct validity of the parental scale version was determined performing factor analysis of obtained results, applying principal component analysis and Varimax rotation. The screen-test method extracted two factors with Eigen values greater than 1. The first factor thus was related mainly to non-invasive dental treatments, while the second factor was mainly related to invasive dental treatments (Table 1).

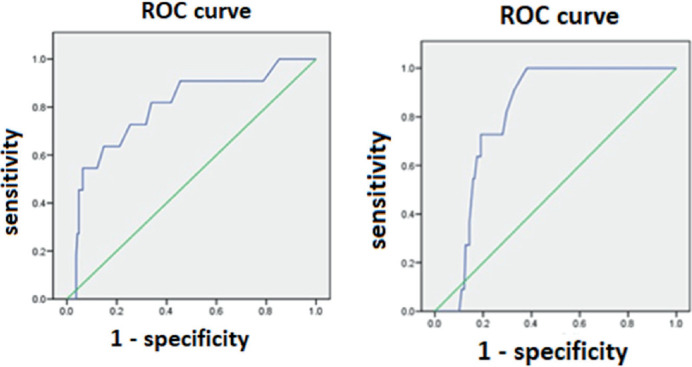

The analysis of obtained child and dentist-observer data resulted in Area Under a Curve (AUC), presented in Figure 1 and Table 2. The cut-off score on the child scale version was determined in a way that the points with the highest product of sensitivity and specificity were identified, which corresponded to certain values of the scores on the scale. Since there were two such places, two cut-off scores were determined, namely 37 and 43, respectively (Table 2). The range of results between these two borderline score values could belong to child participants with subclinical manifestations of DFA presence.

Figure 1. Display of the ROC curve on the child and parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale results.

Table 2. Determination of cut-off values of the child version of CFSS-DS-mod scale.

| AUC value of the child version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale | |||||||

| AUC | stand. error | asymptot. sig. | |||||

| 0.798 | 0.073 | 0.001 | |||||

| asymptotic 95% confidence interval | |||||||

| lower bound | upper bound | ||||||

| 0.655 | 0.940 | ||||||

| Coordinates of ROC curve / child version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale / | |||||||

| (cut-off score of referent variable / Venham scales / was 5) | |||||||

| score value | sensitivity x specificity | score value | sensitivity x specificity | score value | sensitivity x specificity | score value | sensitivity x specificity |

| 16.00 | 0.00 | 26.50 | 0.48 | 36.50 | 0.54 | 48.00 | 0.26 |

| 17.50 | 0.06 | 27.50 | 0.52 | 37.50 | 0.48 | 49.50 | 0.18 |

| 18.50 | 0.10 | 28.50 | 0.54 | 38.50 | 0.48 | 50.50 | 0.09 |

| 19.50 | 0.15 | 29.50 | 0.50 | 39.50 | 0.50 | 51.50 | 0.00 |

| 20.50 | 0.19 | 30.50 | 0.52 | 41.00 | 0.50 | 52.50 | 0.00 |

| 21.50 | 0.26 | 31.50 | 0.54 | 42.50 | 0.51 | 53.50 | 0.00 |

| 22.50 | 0.33 | 32.50 | 0.50 | 43.50 | 0.43 | 54.50 | 0.00 |

| 23.50 | 0.38 | 33.50 | 0.50 | 44.50 | 0.43 | 56.00 | 0.00 |

| 24.50 | 0.44 | 34.50 | 0.52 | 45.50 | 0.43 | 68.50 | 0.00 |

| 25.50 | 0.50 | 35.50 | 0.52 | 46.50 | 0.26 | 81.00 | 0.00 |

Similarly to previous, the analysis of parental and dentist-observer data resulted in AUC, presented in Figure 1 and Table 3. Two cut-off scores were determined, namely 36 and 44, respectively (Table 3). The range of scores between these two borderline score values could belong to child participants with subclinical manifestations of DFA presence, according to their parent’s assessments.

Table 3. Determination of cut-off values of the parental version of CFSS-DS-mod scale.

| AUC value of the parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale | |||||||

| AUC | stand. error | asymptot. sig. | |||||

| 0.808 | 0.035 | 0.001 | |||||

| asymptotic 95% confidence interval | |||||||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| 0.739 | 0.876 | ||||||

| Coordinates of ROC curve / parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale / | |||||||

| (cut-off score of referent variable / Venham scale / was 5) | |||||||

| score value | sensitivity x specificity | score value | sensitivity x specificity | score value | sensitivity x specificity | score value | sensitivity x specificity |

| 16.00 | 0.00 | 30.50 | 0.45 | 44.50 | 0.52 | 59.00 | 0.00 |

| 17.50 | 0.03 | 31.50 | 0.49 | 45.50 | 0.52 | 60.50 | 0.00 |

| 18.50 | 0.05 | 32.50 | 0.53 | 46.50 | 0.52 | 61.50 | 0.00 |

| 19.50 | 0.10 | 33.50 | 0.55 | 47.50 | 0.46 | 63.00 | 0.00 |

| 20.50 | 0.12 | 34.50 | 0.59 | 48.50 | 0.46 | 65.50 | 0.00 |

| 21.50 | 0.15 | 35.50 | 0.62 | 49.50 | 0.31 | 67.50 | 0.00 |

| 22.50 | 0.20 | 36.50 | 0.61 | 50.50 | 0.23 | 68.50 | 0.00 |

| 23.50 | 0.22 | 37.50 | 0.58 | 51.50 | 0.24 | 70.00 | 0.00 |

| 24.50 | 0.24 | 38.50 | 0.52 | 52.50 | 0.24 | 71.50 | 0.00 |

| 25.50 | 0.28 | 39.50 | 0.54 | 53.50 | 0.08 | 74.00 | 0.00 |

| 26.50 | 0.32 | 40.50 | 0.55 | 54.50 | 0.08 | 77.00 | 0.00 |

| 27.50 | 0.35 | 41.50 | 0.56 | 55.50 | 0.08 | 79.00 | 0.00 |

| 28.50 | 0.38 | 42.50 | 0.58 | 56.50 | 0.00 | 81.00 | 0.00 |

| 29.50 | 0.40 | 43.50 | 0.59 | 57.50 | 0.00 | ||

Types of informant

As the distribution of the obtained results was asymmetric (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p<0.0005), nonparametric tests were performed to examine the existence of statistically significant correlations and differences between the examined variables.

The results showed that there were statistically significant correlations in assessing of DFA presence in a way that the correlation was strongest between the parents of the child participants and the dentist-observer (Spearman ρ = 0.699, p<0.0005), slightly weaker between the child participants and the dentist-observer (Spearman ρ = 0.496, p<0.0005), and the lowest between children and their parents (Spearman ρ = 0.323, p<0.0005). Also, statistically significant differences were found between the average scores on the child and the parental scale version in the sense that the average scores were statistically significantly higher in the parental compared to the child scale version (Wilcoxon Z = -6.481; p<0.0005).

By establishing cut-off scores on the child and parental scale versions, assessment of the existence of differences in the DFA presence between children, their parents, and the dentist-observer could be fully examined. This was done by encoding the results on all three scales by the principle that the value of 1 meant the existence of DFA presence (existence of DBP in Venham scale), while the value of 0 meant their absence. Child patients with subclinical manifestations of DFA presence were also considered and included in the parental and child scale versions. The results of the Wilcoxon signed rank test showed that there were statistically significant differences in the DFA presence assessment between the parents (higher DFA levels; Z = -3.833, p<0.0005) and their children, and between dentist-observer (higher DFA levels; Z = -3.53, p<0.0005) and child participants, while these were not statistically confirmed between the dentist-observer and the parents of child participants. This was confirmed by the Cohen’s measure of inter-rater reliability: the largest one between the parents and the dentist-observer with more than a good measure of agreement (Κ = 0.626, p<0.0005), moderate between the results of the child participants and the dentist-observer (Κ = 0.453, p<0.0005), and only with slight agreement between the results of the children and their parents (Κ = 0.149, p = 0.016).

5. DISCUSSION

The internal consistency reliability of the parental scale version (α = 0.955) was even higher than that of the child scale version (α = 0.907). This difference could also be roughly interpreted as the ability of parents to assess the DFA presence in their children more accurately, compared to the own ability of child participants. The same situation was with the construct validity of the parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale in the study, which clarified most of the results obtained with its two-dimensional concept of the DFA appearance, both with respect to the child version of this scale and also with studies of original version of CFSS-DS scale and its modifications (1). These findings confirmed that the parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale was a highly reliable and valid psychometric instrument for measuring the DFA presence in clinical setting in children aged from 9 to 12 in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Studies of the DFA presence in the pediatric population were known to be based on different cut-off score values on the original CFSS-DS scale (4). Ten Berge et al. proposed two cut-off scores on this scale to indicate the portion in the studied pediatric population which was at risk of developing DFA presence, which was named as borderline area for DFA presence. This kind of child DFA presence but did not shown because of the learned patterns of coping with dental stressors (3). Also, another study published in Greece mentioned also the borderline area between the two determined cut-off scores (10). Defining the presence of a borderline area, as a form of subclinical entity in explaining the DFA occurrence, was consistent with the findings of this study and it should be addressed in future surveys of the DFA presence in children. This could be further strengthened with the fact that, when the child patient had the contact with the stressor within the dental office, further behavioral situations could develop in a way that children with DFA presence understood the feeling and knew how to subsequently cope with it without the DBP expression (11). There were different ways in explaining how the children with DFA presence delt with dental stressors in order not to show their fear and/or anxiety (12-15).

Inter-rater concordance in the assessment of DFA presence between the children, their parents and dentists has been lately observed in several studies. Results regarding children-parents relationship showed modest agreement, or parents tended to rate the DFA presence in their children slightly higher than did the children by themselves (16-18). In the parents-dentists relationship results showed strong agreement and beter anticipation of child behaviour in the office by dental proffesionals. Children expressed more negative dental behaviours in correlation with more stressful dental procedures. Nevertheless, each evaluation method of DFA presence had its own merits and limitations (19-22). Considering the fact that assessments of DFA presence in child participants by their parents were good in our study, this was in support of the fact that they had a fairly good understanding of the child behavior in the dental office. This moment would be essential to prepare child for the dental treatment with the coordination of the dentist and the cooperation of their parents.

6. CONCLUSION

The parental version of the CFSS-DS-mod scale was a reliable and valid psychometric instrument for measuring the DFA presence and with better normative values than the child version of this scale.

When using parental versions of scales to measure the DFA presence in children, their own normative values should be determined and not a priori used previously established values of the child scale versions.

Children aged between the 9 and 12 years verbally underestimated the DFA presence when interviewed. Thus, the assessment of their dental behavior at this age was more realistic by their parents and most accurate by the dentist.

Acknowledgments:

This study was conducted on the basis of the significant human efforts of the dental health care personnel of the Clinic for Preventive and Pediatric Dentistry of the Faculty of Dentistry with Clinics of University of Sarajevo.

Participant Consent Form:

All participants were informed about subject of the study and were consented.

Author’s Contribution:

All authors equally contributed to the conception or design, the work in data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and critical revising and approval of the final version to be published. Final article drafting and proofreading was made by the first author only.

Conflicts of Interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship:

None.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bajrić E, Kobašlija S, Jurić H, Huseinbegović A, Zukanović A. The Reliability and Validity of the Three Modified Versions of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale of 9-12-Year-Old Children in a Clinical Setting in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Acta Med Acad. 2018 May;47(1):1–10. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Matthews DE, Farewell VT. Basel: Karger; 2007. Using and understanding medical statistics. 4th completely revised and enlarged edition. [Google Scholar]

- [3].ten Berge M, Veerkamp JS, Hoogstraten J, Prins PJ. Childhood dental fear in the Netherlands: prevalence and normative data. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002 Apr;30(2):101–107. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Grisolia BM, Dos Santos APP, Dhyppolito IM, Buchanan H, Hill K, Oliveira BH. Prevalence of dental anxiety in children and adolescents globally: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021 Mar;31(2):168–183. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bajrić E, Kobašlija S, Huseinbegović A, Marković N, Selimović-Dragaš M, Arslanagić Muratbegović A. Factors that determine child behavior during dental treatment. Balk J Dent Med. 2016;20(2):69–77. doi: 10.1515/bdjm-2016-0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bajrić E. Sarajevo: Faculty of Dental Medicine, University of Sarajevo; 2014. Analysis of dental fear and anxiety using different versions of the Dental Subscale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- [7].World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013 Nov 27;310(20):2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Venham L, Gaulin-Kremer E, Munster E, Bengston-Audia D, Cohan J. Interval rating scales for children’s dental anxiety and uncooperative behavior. Paediatr Dent. 1980;2:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Newton JT, Buck DJ. Anxiety and pain measures in dentistry: a guide to their quality and application. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Oct;131(10):1449–457. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boka V, Arapostathis K, Karagiannis V, Kotsanos N, van Loveren C, Veerkamp J. Dental fear and caries in 6-12-year-old children in Greece. Determination of dental fear cut-off points. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2017 Mar;18(1):45–50. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2017.18.01.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Koch G, Poulsen S, Espelid I, Haubek D, editors. Third Edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2017. Pediatric Dentistry: A Clinical Approach. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Morgan AG, Rodd HD, Porritt JM, Baker SR, Creswell C, Newton T, Williams C, Marshman Z. Children’s experiences of dental anxiety. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017 Mar;27(2):87–97. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pop-Jordanova N, Sarakinova O, Pop-Stefanova-Trposka M, Zabokova-Bilbilova E, Kostadinovska E. Anxiety, Stress and Coping Patterns in Children in Dental Settings. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018 Apr 10;6(4):692–697. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Coric A, Banozic A, Klaric M, Vukojevic K, Puljak L. Dental fear and anxiety in older children: an association with parental dental anxiety and effective pain coping strategies. J Pain Res. 2014 Aug 20;7:515–521. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S67692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Crego A, Carrillo-Diaz M, Armfield JM, Romero M. Dental fear and expected effectiveness of destructive coping as predictors of children’s uncooperative intentions in dental settings. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015 May;25(3):191–198. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Paglia L, Gallus S, de Giorgio S, Cianetti S, Lupatelli E, Lombardo G, Montedori A, Eusebi P, Gatto R, Caruso S. Reliability and validity of the Italian versions of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule–Dental Subscale and the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2017 Dec;18(4):305–312. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2017.18.04.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tollili C, Katsouda M, Coolidge T, Kotsanos N, Karagiannis V, Arapostathis KN. Child dental fear and past dental experience: comparison of parents’ and children’s ratings. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2020 Oct;21(5):597–608. doi: 10.1007/s40368-019-00497-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Klein U, Manangkil R, DeWitt P. Parents’ Ability to Assess Dental Fear in their Six- to 10-year-old Children. Pediatr Dent. 2015 Sep-Oct;37(5):436–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nelson TM, Huebner CE, Kim A, Scott JM, Pickrell JE. Parent-reported distress in children under 3 years old during preventive medical and dental care. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2015 Jun;16(3):283–290. doi: 10.1007/s40368-014-0161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nelson TM, Huebner CE, Kim AS, Scott JM. Parent, Dentist, and Independent Rater Assessment of Child Distress During Preventive Dental Visits. J Dent Child (Chic) 2016;83(2):71–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sivakumar P, Gurunathan D. Behavior of Children toward Various Dental Procedures. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2019 Sep-Oct;12(5):379–384. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yon MJY, Chen KJ, Gao SS, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. An Introduction to Assessing Dental Fear and Anxiety in Children. Healthcare (Basel) 2020 Apr 4;8(2):86. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]