Abstract

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) affects nearly 20% of all hospitalised patients and is associated with poor outcomes. Long-term complications can be partially attributed to gaps in kidney-focused care and education during transitions. Building capacity across the healthcare spectrum by engaging a broad network of multidisciplinary providers to facilitate optimal follow-up care represents an important mechanism to address this existing care gap. Key participants include nephrologists and primary care providers and in-depth study of each specialty’s approach to post-AKI care is essential to optimise care processes and healthcare delivery for AKI survivors.

Methods and analysis

This explanatory sequential mixed-methods study uses survey and interview methodology to assess nephrologist and primary care provider recommendations for post-AKI care, including KAMPS (kidney function assessment, awareness and education, medication review, blood pressure monitoring and sick day education) elements of follow-up, the role of multispecialty collaboration, and views on care process-specific and patient-specific factors influencing healthcare delivery. Nephrologists and primary care providers will be surveyed to assess recommendations and clinical decision-making in the context of post-AKI care. Descriptive statistics and the Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test will be used to compare results between groups. This will be followed by semistructured interviews to gather rich, qualitative data that explains and/or connects results from the quantitative survey. Both deductive analysis and inductive analysis will occur to identify and compare themes.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been reviewed and deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Mayo Clinic (IRB 20–0 08 793). The study was deemed exempt due to the sole use of survey and interview methodology. Results will be disseminated in presentations and manuscript form through peer-reviewed publication.

Keywords: nephrology, acute renal failure, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The sampling frame for both the quantitative and qualitative strands broadly represents the spectrum of post-AKI care providers, enhancing the generalisability of findings.

Iterative qualitative data collection and analysis and inclusion of an inductive analytic approach will facilitate adaptation of the sampling approach and interview guide over the course of the study and allow for exploration of new or unanticipated themes.

Integration of data among and between both strands to explore concordance or discordance enhances the veracity and internal validity of study findings.

Non-response bias is a concern with survey research and therefore some basic demographic information will be collected for the entire invited sample (including non-responders) to assess and describe this.

This survey measures provider recommendations through a small number of simulated cases and results may not accurately reflect real-time decisions made in practice; therefore, clinician views are explored in greater detail through qualitative interviews.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) affects nearly 20% of all hospitalised patients1 and the 80%–90% who survive hospitalisation are at higher risk for poor long-term outcomes compared with those discharged free from AKI. These complications, which include a 1.5–2.5-fold higher risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD), a 1.9-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease2–7 and frequent rehospitalisations,2 decrease the quality of life for AKI survivors and strain healthcare resources.8–10

This significant risk of poor outcomes can be partially attributed to gaps in kidney-focused care and education during transitions. A minority of AKI survivors receive dedicated kidney health follow-up after discharge and prescription of potentially nephrotoxic medications occurs commonly in AKI survivors.11 12 The Acute Disease Quality Initiative, an internationally recognised group of experts in kidney health, recommends a multidisciplinary approach to post-AKI care that includes implementation of the KAMPS framework (table 1) and encourages follow-up with a nephrology specialist for those with severe and/or prolonged AKI.13 Each KAMPS element is designed to minimise AKI complications and promote patient engagement with kidney health. We previously demonstrated that 1 in 5 AKI survivors fail to receive a serum creatinine assessment (the ‘K’ in KAMPS) within 30 days of discharge. Incidence of a kidney function assessment and a healthcare visit (a necessary step to achieve the other KAMPS elements including education, medication review, blood pressure individualisation and counselling) was only 70% at 30 days.14 Evidence describing the optimal processes for achieving of these objectives has yet to be elucidated. The limited reports of existing post-AKI care models describe routine incorporation of laboratory monitoring, patient education and medication review.15–18 These models primarily rely on nephrologists to oversee all elements of kidney health follow-up and education, however only a small portion of AKI survivors engage in this follow-up. Studies demonstrate that individuals at highest risk for poor outcomes, such as those with AKI requiring dialysis, pre-existing CKD, and minimal kidney function recovery at the time of hospital dismissal, are seen by a nephrologist in only 36%–43% of cases19 20 and the overall incidence of nephrology follow-up in AKI survivors may be as low as 8%.14 21 Additionally, concerns have been raised regarding the accessibility and scalability of AKI survivor care models dependent solely on nephrologists. Specifically, limitations include lack of access to nephrology specialty care, particularly in low-income and rural areas, patient reluctance to add more doctors to their healthcare team, and the inability of nephrology practices to meet the growing demand for their services.17 22 23 For these reasons, the broad implementation of AKI survivor care and components of the KAMPS framework cannot rely solely on nephrology specialists. Thus, there is a critical need to develop new pathways for delivery of key elements of post-AKI care and prioritise referral to nephrology specialty care for those highest risk patients who stand to benefit most.

Table 1.

Components of kidney follow-up care

| K | Kidney function assessment with laboratory testing |

| A | Awareness and education |

| M | Medication reconciliation and review |

| P | Individualised blood Pressure monitoring |

| S | Sick day education |

Building capacity across the healthcare spectrum by engaging a broader network of providers to facilitate follow-up care represents a key mechanism to address these needs.24 Primary care providers (PCPs) play an integral role in facilitating continuity of care during transitions from the hospital to a community setting, often using established transition models to reduce emergency department visits, rehospitalisations, costs, and improve quality of life and self-rated health.25–29 These cost-effective, team-based strategies could be successfully leveraged to deliver better care for AKI survivors, as PCPs and nephrologists frequently and collaboratively care for patients with kidney disease.22 30–32 To optimise cooperative care processes and healthcare delivery for AKI survivors, additional study is needed to understand how nephrologists and PCPs approach post-AKI care after hospitalisation, including implementation of the KAMPS framework.

This manuscript presents a mixed-methods protocol for a study to answer the research question: how do PCPs’ and nephrologists’ recommendations for post-AKI care compare? We will explore methods for implementing KAMPS elements, multispecialty collaboration, and care process-specific and patient-specific factors influencing healthcare delivery.

Methods and analysis

Overview and design

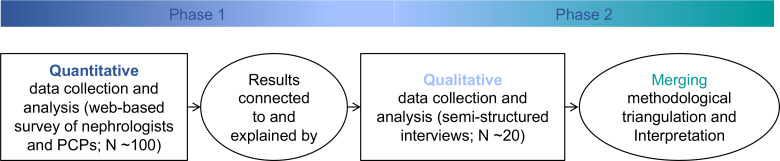

We will perform an explanatory sequential mixed-methods study to assess PCP and nephrologist recommendations for kidney follow-up care in the context of AKI survivorship during transitions of care (figure 1). The quantitative strand will be guided by a postpositivism worldview to assess clinical decision-making using case-based scenarios. Qualitative research will employ a realism framework to explain differences and further explore the perspectives of the two groups. This study was reviewed, deemed ‘exempt’ due to the sole use of survey and interview procedures, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (20–0 08 793) at Mayo Clinic on 21 October 2020, and data collection is currently ongoing. All research will be conducted during the global COVID-19 pandemic and is anticipated to conclude in 2022.

Figure 1.

Explanatory sequential mixed-methods study design.

Patient and public involvement

No patient or member of the public was directly involved in the study design. The research question and outcome measure(s) in both quantitative and qualitative strands were informed by patients’ priorities, experiences and preferences sourced from published data from clinical trials, qualitative patient interviews and patient-inclusive workshops and focus groups.16 17 33 34

Phase 1—quantitative strand

Survey development

A survey instrument was developed with the objective to assess provider recommendations and clinical decision-making in the context of post-AKI care (online supplemental appendix 1). Survey questions were developed using an emerging contextual framework, KAMPS, for construct validity. The KAMPS framework is derived from expert recommendations for components of kidney follow-up care.13 The survey measures behaviour related to kidney function monitoring, recognition of CKD, comorbid disease management, medication and lifestyle modification, and nephrology specialist referral through fictitious, case-based questions. The KAMPS framework primarily addresses what components of care should be delivered but not how to meet those goals. After construction by select study team members (HPM, AKK, EFB), cases were pilot tested and reviewed by board certified physicians in nephrology and primary care (KBK, RGM), study team members with >5 years of postgraduate experience in AKI survivorship care. Additional pilot testers were then recruited from among trainees in nephrology and primary care. Respondent debriefings were conducted with pilot testers to assess the content and face validity of the survey, and results used to iteratively refine the items. Construct validity is derived from comparison to KAMPS criteria, case review by study team members internationally recognised as experts in AKI care quality (KBK, EFB),13 and existing literature demonstrating these specific gaps in post-AKI transitions of care.14 17 35–37

bmjopen-2021-058613supp001.pdf (83.1KB, pdf)

Sample and study setting

The sampling frame will include physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs; nurse practitioner or physician assistant) within the Divisions of Nephrology and Primary Care who provide posthospital care for AKI survivors at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Florida, Arizona and the Mayo Clinic Health System. The Mayo Clinic Health System includes clinics, hospitals and other healthcare facilities across southern Minnesota, western Wisconsin and northeastern Iowa.38 Facilities include large regional medical centres, community hospitals and rural primary care clinics that collectively offer over 100 medical and surgical services and specialties that serve patients in their communities. Resources are shared across the Mayo Clinic Enterprise, including Florida, Arizona and the Health System. This sampling approach targets individuals affiliated with both academic and community or rural settings, and individuals with patients from a variety of sociodemographic backgrounds. Members of the Division of Nephrology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester provide specialty services to patients within the Mayo Clinic Health System on a referral basis through in-person appointments at multiple health system sites, including outreach clinics in rural areas. Additional nephrology physicians and APPs are employed by individual health system sites. Availability and provider experience with telemedicine increased prior to the study period due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Within the Mayo Clinic Enterprise, telemedicine is employed by multiple disciplines (eg, medicine, nursing, pharmacy) when clinically appropriate and as supported by state and federal governments. Transitional and in-home primary care programmes were implemented in select locations within the Mayo Clinic Enterprise prior to the pandemic.29 39 In 2021, a new transitional post-AKI care programme was piloted in primary care in Rochester.40 No formal changes were made to nephrology or primary care posthospital follow-up practices and new patient capacity was unchanged. Email addresses will be obtained from departmental contact lists. Respondents must certify they have been in practice a minimum of 1 year following terminal postgraduate medical training, practice in an outpatient clinic setting a minimum of ½ day per week, and have experience caring for patients recently discharged from the hospital. Remuneration will not be offered for completing the survey.

Data collection

Demographic data collected includes sex, specialty, degree, practice location (Mayo Clinic Rochester, Mayo Clinic Arizona, Mayo Clinic Florida or the Mayo Clinic Health System), location of medical training (yes/no to any completed at a non-Mayo Clinic site) and years in practice. The invitation to participate in the study will be extended via email and the survey will be administered using RedCap survey technology. The survey will be active for a period of 3 weeks before a reminder email will be distributed to all individuals who have not yet completed the survey. The outcomes measured will be the survey answers selected by respondents.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used for demographic variables in both groups. The Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables will be used to compare results for each question between groups. Select questions (see online supplemental appendix 1) with a ‘best answer’ (eg, based on guideline recommendations, package insert guidance for drug dosing in kidney dysfunction) will be scored, with 1 point assigned for each best answer selected and 0 points assigned for incorrect answers, for a maximum total of 5 points. In cases where a ‘best answer’ cannot be determined, differential responses will be described and compared between groups. Mean scores will be compared between groups using the students t-test. We will use a connecting and merging approach for mixed-methods data integration and results from the survey will inform the sample for the qualitative strand.

Detecting a mean between-group difference (nephrologist vs PCPs) of 2 points, assuming a SD of 2, with 80% power and using an alpha 0.05 will require 18 participants per group. Departmental contact lists indicate 61 providers employed within the included Divisions of Nephrology and over 700 PCPs employed by Mayo Midwest Primary Care. A response rate of 3% (for PCPs) to 29% (for nephrologists) will make it feasible to meet our recruitment targets.

Phase 2—qualitative strand

Sample

Purposeful sampling of survey responders will be used to recruit up to 20 providers, who routinely care for AKI survivors in the postdischarge setting, for semistructured interviews. The final number of participants will be guided by thematic saturation.28 Participants from the quantitative strand will be sampled for variation on key factors including sex, specialty, provider type (physician or APP), and practice setting to provide insight from the breadth of providers represented in the sampling frame and explain survey results that are of greatest interest. Additional individuals will be recruited from among the sampling frame identified in the quantitative strand, if needed to achieve thematic saturation. Data collection and analysis will be iterative and additional interviews will be added if other important viewpoints are revealed. This will facilitate the selection of information-rich cases while capturing significant variations of experience.

Data collection

An open-ended question guide was developed using a pragmatism approach to gather rich, qualitative data on provider views on timing and implementation of KAMPS elements, multispecialty collaboration for post-AKI care, influential patient-specific factors, and challenges and methods to facilitate care improvements for these patients (online supplemental appendix 2). It will also be informed by emerging themes from quantitative data analysis, including differences between groups based on specialty and/or other key demographics. Interviews will be conducted by a consistent member of the study team who is an expert in the field of qualitative research (DMF) for optimal dependability. They will be carried out via phone and will be recorded and transcribed verbatim with permission from the participants. The interviewer will record field notes following the conclusion of each interview and reflexivity will be acknowledged through reflective journaling to enhance neutrality.

bmjopen-2021-058613supp002.pdf (97.2KB, pdf)

Data analysis and integration

Interview transcripts will be uploaded into NVivo software, a qualitative data analysis tool. NVivo aids investigators by facilitating coding of source data, data sorting and identification of concepts indicative of themes. Codes assign meaning to pieces of data or text and facilitate organisation, categorisation and interpretation. Both deductive analysis (a priori codes related to the KAMPS framework domains) and inductive analysis (identification of emerging themes) will occur. Emerging themes will be discussed by content experts (HPM, EFB) and the qualitative data analyst (DMF) to ensure they capture the full range and depth of interview data, and a preliminary codebook will be developed. This codebook will then be applied to all source data. Themes identified by nephrology specialists and PCPs will be compared. The quantitative and qualitative data will be integrated using joint display tables organised according to KAMPS domains as well as highlight areas of complementarity (eg, domains describing different facets of the larger phenomenon of care transitions in AKI survivors), concordance and discordance (similarities or differences between nephrologists and PCPs, location of primary practice site, and/or between quantitative and qualitative datasets). Divergence will be addressed through reconciliation, which will include careful examination of existing biases, reviewing data with a deliberate focus on understanding divergent results, and formation of hypotheses about divergence and why it occurred. These can be explored through further data collection or as a part of future research efforts. Investigators will examine and disclose important changes or new discoveries that have occurred in the evolving field of post-AKI care to promote dependability of study findings.

Discussion

Integrating PCPs into the AKI survivor care pathway represents an important strategy to address the limitations of existing practices that rely primarily on nephrologists. AKI survivors express concerns about increasing the number of specialists involved in their outpatient care and the travel time required to reach tertiary care centres where specialists are located.17 41 Providing core components of post-AKI care in the patients’ home of primary care may increase the frequency and timeliness of kidney follow-up in this population. Uncovering a deeper understanding of PCPs’ and nephrologists’ existing beliefs and approaches to post-AKI care is critical to optimising cooperation and communication between disciplines. This information will also assist in identifying opportunities to improve implementation of best practices, such as the KAMPS framework. Results from this study will describe contemporary recommendations for post-AKI care from a diverse group of providers involved in AKI survivor care transitions, with a focus on best practices, multispecialty collaboration and healthcare delivery processes. Future research can include validation of these findings in other health systems and practitioners operating in unique settings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HPM, EFB, AKK designed and revised the survey instrument; HPM conducted pilot testing of the survey instrument; RGM, ADR, KBK, JMG reviewed and revised the survey instrument; HPM, EFB, DMF, JMG conceived the methods for the qualitative strand, including sampling approach, data collection and analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the study protocol, as well as this manuscript submission.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Mayo Midwest Pharmacy Research Committee, Mayo Midwest Clinical Practice Committee Innovation Award, American College of Clinical Pharmacy, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under award number K23AI143882 (PI; EFB), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality HS028060-01 (PI; EFB). The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, writing the report or the decision to submit the report for publication. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data publically available for this protocol.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Kashani K, Shao M, Li G, et al. No increase in the incidence of acute kidney injury in a population-based annual temporal trends epidemiology study. Kidney Int 2017;92:721–8. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siew ED, Parr SK, Abdel-Kader K, et al. Predictors of recurrent AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:1190–200. 10.1681/ASN.2014121218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int 2012;81:442–8. 10.1038/ki.2011.379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sawhney S, Marks A, Fluck N, et al. Post-discharge kidney function is associated with subsequent ten-year renal progression risk among survivors of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 2017;92:440–52. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heung M, Steffick DE, Zivin K, et al. Acute kidney injury recovery pattern and subsequent risk of CKD: an analysis of Veterans health administration data. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:742–52. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pannu N, James M, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Association between AKI, recovery of renal function, and long-term outcomes after hospital discharge. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:194–202. 10.2215/CJN.06480612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Odutayo A, Wong CX, Farkouh M, et al. AKI and long-term risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:377–87. 10.1681/ASN.2016010105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury-epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol 2014;10:193–207. 10.1038/nrneph.2013.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Villeneuve P-M, Clark EG, Sikora L, et al. Health-related quality-of-life among survivors of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:137–46. 10.1007/s00134-015-4151-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nisula S, Vaara ST, Kaukonen K-M, et al. Six-month survival and quality of life of intensive care patients with acute kidney injury. Crit Care 2013;17:R250–8. 10.1186/cc13076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allen AS, Forman JP, Orav EJ, et al. Primary care management of chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:386–92. 10.1007/s11606-010-1523-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US renal data system 2016 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2017;69:A7–8. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kashani K, Rosner MH, Haase M, et al. Quality improvement goals for acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;14:941–53. 10.2215/CJN.01250119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barreto EF, Schreier DJ, May HP. Adequacy of kidney follow-up among acute kidney injury survivors after hospital discharge: a population-based cohort study. Am J Nephrol 2021;52:817–26. 10.1159/000519375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ortiz-Soriano V, Alcorn JL, Li X, et al. A survey study of self-rated patients’ knowledge about AKI in a post-discharge AKI clinic. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2019;6:205435811983070–11. 10.1177/2054358119830700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silver SA, Goldstein SL, Harel Z, et al. Ambulatory care after acute kidney injury: an opportunity to improve patient outcomes. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2015;2:71. 10.1186/s40697-015-0071-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Silver S, Adhikari N, Bell C. Nephrologist follow-up versus usual care after an acute kidney injury hospitalization (fusion). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;CJN.17331120. 10.2215/CJN.17331120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh G, Hu Y, Jacobs S. Post-Discharge mortality and rehospitalization among participants in a comprehensive acute kidney injury rehabilitation program. Kidney 2021;360:1424–33. 10.34067/KID.0003672021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karsanji DJ, Pannu N, Manns BJ, et al. Disparity between nephrologists' opinions and contemporary practices for community follow-up after AKI hospitalization. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:1753–61. 10.2215/CJN.01450217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harel Z, Wald R, Bargman JM, et al. Nephrologist follow-up improves all-cause mortality of severe acute kidney injury survivors. Kidney Int 2013;83:901–8. 10.1038/ki.2012.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siew ED, Peterson JF, Eden SK, et al. Outpatient nephrology referral rates after acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:305–12. 10.1681/ASN.2011030315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greer RC, Liu Y, Cavanaugh K, et al. Primary care physicians' perceived barriers to nephrology referral and co-management of patients with CKD: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1228–35. 10.1007/s11606-019-04975-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parker MG, Pivert KA, Ibrahim T, et al. Recruiting the next generation of nephrologists. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2013;20:326–35. 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vijayan A, Abdel-Rahman EM, Liu KD, et al. Recovery after critical illness and acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;16:1601–9. 10.2215/CJN.19601220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–8. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wee S-L, Loke C-K, Liang C, et al. Effectiveness of a national transitional care program in reducing acute care use. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:747–53. 10.1111/jgs.12750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gardner R, Li Q, Baier RR, et al. Is implementation of the care transitions intervention associated with cost avoidance after hospital discharge? J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:878–84. 10.1007/s11606-014-2814-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takahashi PY, Naessens JM, Peterson SM, et al. Short-term and long-term effectiveness of a post-hospital care transitions program in an older, medically complex population. Healthc 2016;4:30–5. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCoy RG, Peterson SM, Borkenhagen LS, et al. Which readmissions may be preventable? lessons learned from a posthospitalization care transitions program for high-risk elders. Med Care 2018;56:693–700. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brimble KS, Boll P, Grill AK, et al. Impact of the kidneywise toolkit on chronic kidney disease referral practices in ontario primary care: a prospective evaluation. BMJ Open 2020;10:e032838. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Neale EP, Middleton J, Lambert K. Barriers and enablers to detection and management of chronic kidney disease in primary healthcare: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol 2020;21:83. 10.1186/s12882-020-01731-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haley WE, Beckrich AL, Sayre J, et al. Improving care coordination between nephrology and primary care: a quality improvement initiative using the renal physicians association toolkit. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:67–79. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Siew ED, Liu KD, Bonn J, et al. Improving care for patients after hospitalization with AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:2237–41. 10.1681/ASN.2020040397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Silver SA, Siew ED. Follow-Up care in acute kidney injury: lost in transition. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2017;24:246–52. 10.1053/j.ackd.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kurani S, Hickson LJ, Thorsteinsdottir B, et al. Supplement use by US adults with CKD: a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis 2019;74:862–5. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kurani S, Jeffery MM, Thorsteinsdottir B, et al. Use of potentially nephrotoxic medications by U.S. adults with chronic kidney disease: NHANES, 2011-2016. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:1092–101. 10.1007/s11606-019-05557-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Teaford HR, Barreto JN, Vollmer KJ, et al. Cystatin C: a primer for pharmacists. Pharmacy 2020;8:35. 10.3390/pharmacy8010035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kurani SS, Lampman MA, Funni SA, et al. Association between area-level socioeconomic deprivation and diabetes care quality in US primary care practices. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2138438–14. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takahashi PY, Chandra A, McCoy RG, et al. Outcomes of a nursing home-to-community care transition program. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:2440–6. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barreto EF, May HP, Schreier DJ, et al. Development and feasibility of a multidisciplinary approach to AKI survivorship in care transitions: research letter. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2022;9:205435812210812. 10.1177/20543581221081258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Silver SA, Saragosa M, Adhikari NK, et al. What insights do patients and caregivers have on acute kidney injury and posthospitalisation care? A single-centre qualitative study from Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021418. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058613supp001.pdf (83.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-058613supp002.pdf (97.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data publically available for this protocol.