Be kind, but be fierce. You are needed now more than ever before. Take up the mantle of change. For this is your time.

Sir Winston Churchill

It has been more than a year since the appearance of COVID-19 in Wuhan (China) and 12 months since the first state of alarm was declared in Spain. New vaccines have recently been authorized in Europe, new variants of the virus have emerged, and the accumulated incidence has again increased. All this has compelled governments in Europe to re-introduce quarantine measure and to warn of an imminent fourth wave. Despite the health and economic impact of COVID-19, we cannot neglect other situation that may have been aggravated by the pandemic, and will become apparent in the near future.

JAMA recently published a series of articles analysing and comparing the increase in excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes during the first months of the pandemic in the US and other countries.1, 2 In the US, at least 33% of the 20% increase in expected deaths in the US, for example, was not directly attributed to COVID but to an increase in deaths associated with other diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular disease. The real tsunami, after so many waves of COVID, could be the neglect, delayed treatment, or substandard treatment of other diseases.1

In Spain, organ donation and transplant activity fell drastically in 2020, leading to a foreseeable increase in overall mortality and a high rate of COVID-related mortality among recipients.3 Estimates suggest that during the first 12 weeks of peak disruption, more than half a million scheduled surgeries were cancelled in Spain, and over 28 million worldwide.4 Concerns have also been raised about the consequences of delaying or suspending surgery – up to 80% of colorectal cancer interventions were cancelled5 – and the risk of substandard management of patients scheduled for cancer interventions and other surgeries.6 Surgery must continue, and hospitals must be fully prepared in terms of material and human resources, and make every attempt to ensure that patients undergo surgery in the best possible conditions.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Another consequence of COVID has been a reduction in the number of blood donations, leading to a potential shortage of plasma-derived medicinal products in the medium term. According to data from internal reports sent during the first wave of the pandemic, between weeks 11 and 26 the number of blood donations fell by 20% compared to 2018 figures (Fig. 1 ), and by around 5%–10% annually (estimate from personal conversation with the directors of blood transfusion centres, in the absence of published data).8 At the start of 2021, the disruptions caused by Storm Filomena further aggravated the shortage of blood products in some autonomous communities, compelling regional authorities to launch “donation marathon” campaigns.

Figure 1.

Blood donation in Spain during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yellow line: % difference in donation each week compared to the weekly average in 2018.

Given the situation and the absence of effective treatment for COVID-19, convalescent plasma therapy – hopefully hyperimmune – is one of the few options available,9 and individuals that are COVID-immune or have recovered from the disease are now being asked to donate blood for this purpose. This, however, could lead to a shortage of plasma-derived medicinal products for non-COVID patients next year.

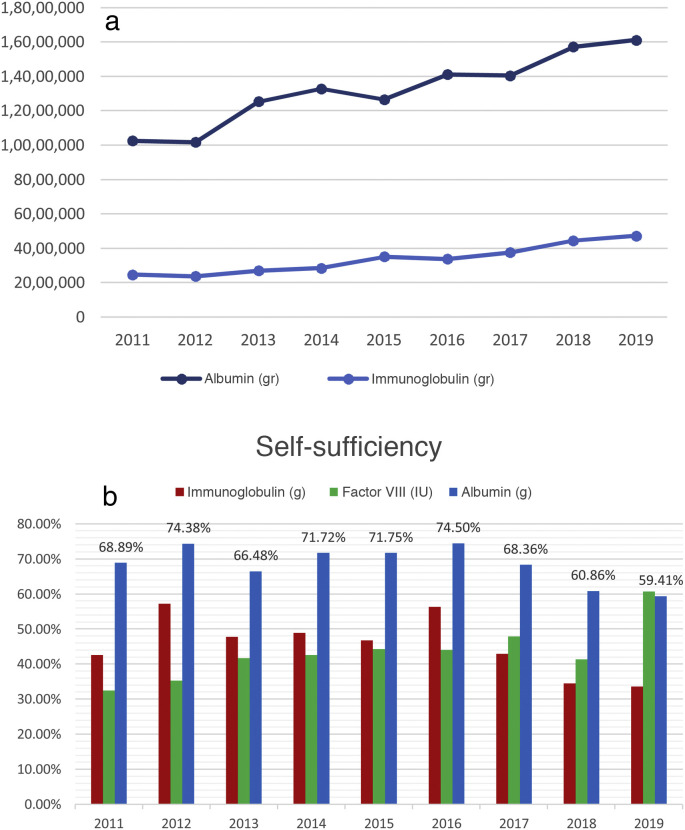

The recent release of national blood donation and transfusion figures for 20198 have raised some concerns. According to the annual reports issued by the Information System of the Ministry of Health,8 blood donations have fallen by 6.6% since 2010, despite the increase in the population, while consumption of albumin and immunoglobulin has increased by 58% and 99.6%, respectively, since 2012 (Fig. 2 a). This serious imbalance, according to these reports,5 has meant that in 2019 Spain is no longer “self-sufficient”, defined as the “capacity of a nation or region to meet the demand for blood, blood components and blood products of the entire population from blood/plasma donated by the citizens themselves”, as it has not been able to satisfy more than 59.4% of national consumption of albumin, 33.5% of immunoglobulin, and 60.7% of plasmatic factor VIII (Fig. 2b). Based on Ministry data,5 Spain has accumulated a deficit of around 10 million vials of Albuplan® 20%, or between 4 and 10 times the annual production, since 2011. In 2019, 265,844 more litres of plasma (more than a million more whole blood donations or about 440,000 apheresis) would have been needed to be self-sufficient in albumin alone.

Figure 2.

(a) Evolution of albumin and immunoglobulin consumption. (b) Evolution of “self-sufficiency” in plasma-derived medicinal products 2011–2019 in Spain (immunoglobulin, albumin and factor VIII).

Self-sufficiency: “capacity of a nation or region to meet the demand for blood, blood components and blood products of the entire population from blood/plasma donated by the citizens themselves”.

This is why action is needed now more than ever,10 and measures must be introduced to promote a national patient blood management (PBM) programme. It is not a matter of reducing blood consumption, but rather of optimizing the use of blood to achieve the best, most efficient, clinical outcomes.10, 11, 12 The WHO has already urged all countries, national health authorities, and health providers to implement this call to action in June 2010. The project launched by the European Commission led to the publication of 2 documents in March 201713, 14 that were distributed to all scientific societies, hospital managers and health authorities. In February 2020, the WHO published the “WHO action framework to advance universal access to quality and safe blood and blood components for transfusion and plasma-derived medicinal products”.15 The strategic objectives of the action framework include the implementation of PBM programmes15 to avoid unnecessary blood transfusions, standardise blood transfusion in clinical practice, reduce the high rate of inappropriate and unnecessary transfusions, and promote the treatment of anaemia and clotting disorders, among others.

We share the WHO’s concerns about the lack of access to safe, quality-assured plasma-derived medicinal products, and call on health authorities, hospital managers and colleagues in Spain to optimise the use of blood and blood products. This, as recommended by the European Commission13, 14 and the WHO,15 involves the urgent implementation of a state plasmapheresis programme and the development of mandatory PBM programmes in all public and private hospitals in Spain. Now is the time to avoid future shortages of plasma-derived medicinal products due to low donation rates or unnecessary blood transfusions by introducing PBM programmes12 and implementing all the PBM strategies recommended in ERAS guidelines6, 12, 16 across the board in the Spanish national healthcare system.

Funding

The corresponding author has received financial support to attend congresses, speakers fees and course fees, and fees for teaching material from Uriach-Vifor, Sandoz, Zambon y Jansen.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Ino Fornet. Anesthesiology and Resuscitation Service. Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (Madrid).

Dr. Javier Ripollés Melchor. Anesthesiology Service. Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor de Madrid. Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal (GERM). Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud (Zaragoza).

Dr. Inma Roig. Servicio de Hematología. Hospital Parc Taulí (Sabadell).

Dr. Carlos Areal. Axencia Galega de Sangue, Órganos e Tecidos (Santiago de Compostela).

Dr. Íñigo Romón Alonso. Servicio de Hematología y Hemoterapia. Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla (Santander).

Dr. José Manuel Ramírez. Servicio de Cirugía General. Hospital Clínico Universitario (Zaragoza). Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal (GERM). Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud (Zaragoza).

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: García-Erce JA, Jericó C, Abad-Motos A, Rodríguez García J, Antelo Caamaño ML, Domingo Morera JM, et al. PBM: Ahora más que nunca es necesario. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2022;69:351–354.

References

- 1.Woolf S.H., Chapman D.A., Sabo R.T., Weinberger D.M., Hill L., Taylor D.D. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March–July 2020. JAMA. 2020;324:1562–1564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19545. PMID: 33044483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilinski A., Emanuel E.J. COVID-19 and excess all-cause mortality in the US and 18 comparison countries. JAMA. 2020;12 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domínguez-Gil B., Coll E., Ferrer-Fàbrega J., Briceño J., Ríos A. Dramatic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on donation and transplantation activities in Spain. Cir Esp. 2020;98:412–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2020.04.012. PMID: 32362364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnal-Velasco D., Planas-Roca A., García-Fernández J., Morales-Conde S. Grupo de Trabajo’ Recomendaciones para la programación de cirugía en condiciones de seguridad durante la pandemia COVID-19. Programación de cirugía electiva segura en tiempos de COVID-19. La importancia del trabajo colaborativo. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2021;68:62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De la Portilla de Juan F., Reyes Díaz M.L., Ramallo Solía I. Impact of the pandemic on surgical activity in colorectal cancer in Spain. Results of a national survey. Cir Esp. 2020;S0009-739X:30265–30267. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2020.07.011. . PMID: 32888676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramírez-Rodríguez J.M., García Erce J.A., Arroyo Sebastián A. «Back to the future»: after the pandemic we must intensify recovery. Cir Esp. 2020;S0009-739X:30266–30269. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2020.07.016. . PMID: 32921418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balibrea J.M., Morales-Conde S. Grupo de Trabajo Cirugía-AEC-COVID. Position statement of the surgery-AEC-COVID Working Group of the Spanish Association of Surgeons on the planning of surgical activity during the second wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: surgery must continue. Cir Esp. 2020;S0009-739X:30348–30351. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2020.10.013. ; PMID: 33228971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Informe de actividad de centros y servicios de transfusión 2019. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social; 2020. [Accessed 3 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/medicinaTransfusional/indicadores/docs/Informe_Actividad2019.pdf.

- 9.Ormazabal Vélez I., Induráin Bermejo J., Espinoza Pérez J., Imaz Aguayo L., Delgado Ruiz M., García-Erce J.A. Two patients with rituximab associated low gammaglobulin levels and relapsed covid-19 infections treated with convalescent plasma. Transfus Apher Sci. 2021;19 doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2021.103104. PMID: 33637467 (prensa) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shander A., Goobie S.M., Warner M.A., Aapro M., Bisbe E., Perez-Calatayud A.A., et al. International Foundation of Patient Blood Management (IFPBM) and Society for the Advancement of Blood Management (SABM) Work Group Essential Role of Patient Blood Management in a Pandemic: a call for action. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:74–85. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004844. PMID: 32243296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zalba Marcos S., Plaja Martí I., Antelo Caamaño M.L., Martínez de Morentin Garraza J., Abinzano Guillén M.L., Martín Rodríguez E., et al. Effect of the application of the “Patient blood management” programme on the approach to elective hip and knee arthroplasties. Med Clin (Barc) 2020;155:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2020.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ripollés-Melchor J., Jericó-Alba C., Quintana-Díaz M., García-Erce J.A. From blood saving programs to patient blood management and beyond. Med Clin (Barc) 2018;151:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2018.02.027. PMID: 29691060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Commission. Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. Supporting patient blood management (PBM) in the EU. A practical implementation guide for hospitals. [Accessed 13 January 2021]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/blood_tissues_organs/docs/2017_eupbm_hospitals_en.pdf.

- 14.European Commission. Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. Building national programmes of Patient Blood Management (PBM) in the EU. A guide for health authorities. Bruselas: European Comission; 2017 [Accessed 13 January 2021]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/blood_tissues_organs/docs/2017_eupbm_authorities_en.pdf.

- 15.WHO. Action framework to advance universal access to safe, effective and quality assured blood products. Organización Mundial de la Salud; 2020 [Accessed 13 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/action-framework-to-advance-uas-bloodprods-978-92-4-000038-4.

- 16.Casans Francés R., Ripollés Melchor J., Calvo Vecino J.M., Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal Germ/ERAS-Spain Is it time to integrate patient blood management in ERAS guidelines? Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2015;62:61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2014.12.005. PMID: 25605130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]