This randomized clinical trial investigates the efficacy of trastuzumab and PD-1 inhibitor with CTLA-4 inhibitor or FOLFOX in first-line treatment of advanced ERBB2-positive esophagogastric adenocarcinoma.

Key Points

Question

What is the efficacy of ipilimumab vs FOLFOX in combination with nivolumab and trastuzumab in previously untreated ERBB2-positive esophagogastric adenocarcinoma (EGA)?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 88 patients, the combination of chemotherapy, nivolumab, and trastuzumab showed favorable survival and response compared with historical control, which could not be shown for the chemotherapy-free combination.

Meaning

The high efficacy warrants further randomized evaluation of the addition of a programmed cell death 1 inhibitor to standard trastuzumab and chemotherapy in ERBB2-positive EGA. Chemotherapy should not be replaced by ipilimumab in an unselected ERBB2-positive population.

Abstract

Importance

In metastatic esophagogastric adenocarcinoma (EGA), the addition of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors to chemotherapy has improved outcomes in selected patient populations.

Objective

To investigate the efficacy of trastuzumab and PD-1 inhibitors with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors or FOLFOX in first-line treatment of advanced ERBB2-positive EGA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 2 multicenter, outpatient, randomized clinical trial with 2 experimental arms compared with historical control individually was conducted between March 2018 and May 2020 across 21 German sites. The reported results are based on a median follow-up of 14.3 months. Patients with previously untreated, metastatic ERBB2-positive (local immunohistochemistry score of 3+ or 2+/in situ hybridization amplification positive) EGA, adequate organ function, and eligibility for immunotherapy were included. Data analysis was performed from June to September 2021.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to trastuzumab and nivolumab (1 mg/kg × 4/240 mg for up to 12 months) in combination with mFOLFOX6 (FOLFOX arm) or ipilimumab (3 mg/kg × 4 for up to 12 weeks) (ipilimumab arm).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was survival improvement with a targeted increase of the 12-month overall survival rate from 55% (trastuzumab/chemotherapy—ToGA regimen) to 70% in each arm.

Results

A total of 97 patients were enrolled, and 88 were randomized (18 women, 70 men; median [range] age, 61 [41-80] years). Baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 0 in 54 patients (61%) and 1 in 34 patients (39%); 66 patients (75%) had EGA localized in the esophagogastric junction and 22 in the stomach (25%). Central post hoc biomarker analysis (84 patients) showed PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) combined positive score of 1 or greater in 59 patients (72%) and 5 or greater in 46 patients (56%) and confirmed ERBB2 positivity in 76 patients. The observed overall survival rate at 12 months was 70% (95% CI, 54%-81%) with FOLFOX and 57% (95% CI, 41%-71%) with ipilimumab. Treatment-related grade 3 or greater adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs occurred in 29 and 15 patients in the FOLFOX arm and in 20 and 17 patients in the ipilimumab arm, respectively, with a higher incidence of autoimmune-related AEs in the ipilimumab arm and neuropathy in the FOLFOX arm. Liquid biopsy analyses showed strong correlation of early cell-free DNA increase with shorter progression-free and overall survival and emergence of truncating and epitope-loss ERBB2 resistance sequence variations with trastuzumab treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, trastuzumab, nivolumab, and FOLFOX showed favorable efficacy compared with historical data and trastuzumab, nivolumab, and ipilimumab in ERBB2-positive EGA. The ipilimumab arm yielded similar OS compared with the ToGA regimen.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03409848

Introduction

Globally, 1.7 million new cases of gastric and esophageal cancer occur each year.1 With more than 1.3 million deaths per year, these cancers remain among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 Recurrent or metastatic disease affects about 75% of patients with esophagogastric adenocarcinomas (EGAs) at some point. For these patients, palliative systemic therapy remains the mainstay of treatment.

For EGA that are positive for ERBB2 (formerly HER2) (defined by immunohistochemistry [IHC] 3+ or 2+ and amplification by in situ hybridization [ISH]), the combination of the ERBB2 antibody trastuzumab and chemotherapy is the current standard of care.2,3 This regimen was defined in the ToGA trial2 and subsequently confirmed in the control arm of the JACOB trial (trastuzumab and chemotherapy with or without pertuzumab).3 This standard regimen shows an overall response rate (ORR) of 47% to 48%, a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.7 to 7 months and a median overall survival (OS) of 14.2 to 16 months.2,3 In programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive, ERBB2-negative EGA, the combination of PD-1 inhibition and chemotherapy evolved as new standard of care.4,5 Furthermore, the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab showed clinically meaningful antitumor efficacy in refractory patients favoring the nivolumab, 1 mg/kg, and ipilimumab, 3 mg/kg, schedule.6

While immune checkpoint blockade has entered the treatment armamentarium of ERBB2-negative, PD-L1–positive EGA, it awaits integration into the treatment of ERBB2-positive disease. Molecular synergism of PD-1 inhibition and anti-ERBB2 has been inferred from breast cancer trials suggesting increases in immune cell infiltration and PD-1 expression in response to trastuzumab exposure.7 Clinically, 2 single-arm studies in ERBB2-positive EGA combining the standard of care (trastuzumab and chemotherapy) with pembrolizumab demonstrated favorable outcomes in comparison with historical control.8,9 Furthermore, interim results of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-811 trial comparing pembrolizumab or placebo combined with trastuzumab and chemotherapy showed a significantly increased ORR (74.4% vs 51.9%; P < .001) in favor of the PD-1 inhibitor–containing regimen, resulting in recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of this regimen.10

The Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO) INTEGA trial was designed to evaluate 2 experimental regimen chemotherapy and trastuzumab in combination with PD-1 inhibitor and a chemotherapy-free regimen consisting of trastuzumab, PD-1 inhibitor, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 inhibitor.11

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were 18 years and older with pathologically confirmed ERBB2 positivity (local IHC 3+ or 2+/ISH positive), inoperable, locally advanced or metastatic EGA previously untreated for metastatic disease with either measurable or nonmeasurable disease according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1). Prior neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant treatment was permitted if completed at least 3 months prior to randomization. Further inclusion criteria were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 to 2, and adequate hematologic, hepatic, and kidney function. Exclusion criteria included reduced cardiac ejection fraction (<55%), other cancers within the past 5 years, substantial autoimmune disease or conditions requiring corticosteroids (>10 mg daily prednisone equivalent), and known peripheral neuropathy (defined as greater than grade 1 per National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [NCI CTCAE], version 4.03). The trial protocol is in Supplement 1, and the statistical analysis plan is in Supplement 2. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Randomization

Patients were centrally randomized using a 1:1 allocation ratio to trastuzumab and nivolumab with either FOLFOX (FOLFOX arm) or ipilimumab (ipilimumab arm). Randomization was stratified for prior surgery of the primary tumor (yes vs no) and ERBB2 status (ERBB2 3+ vs ERBB2 2+ and ISH positive).

Procedures

Patients randomized to the ipilimumab arm received trastuzumab, 6 mg/kg (loading dose 8 mg/kg), nivolumab, 1 mg/kg, and ipilimumab, 3 mg/kg, every 3 weeks for a total of 12 weeks. From week 13, patients received trastuzumab, 4 mg/kg, and nivolumab, 240 mg, every 2 weeks. Patients randomized to the FOLFOX arm received trastuzumab, 4 mg/kg intravenously (loading dose 6 mg/kg), nivolumab, 240 mg, and mFOLFOX6 every 2 weeks (oxaliplatin, 85 mg/m2, fluorouracil, 400 mg/m2 bolus, folinic acid, 400 mg/m2, and fluorouracil, 2400 mg/m2 over 46 hours). The overall treatment plan of the INTEGA trial is displayed in eFigure 1 in Supplement 3. Treatment was administered until progression (according to RECIST v1.1), intolerable toxic effects, withdrawal of consent, or secondary resection. Nivolumab treatment was limited to a maximum of 12 months in both arms.

Patients were monitored before each treatment cycle for adverse events (AEs), vital signs, ECOG PS, and laboratory values. Dose modifications were performed according to toxic effects (NCI CTCAE, version 4.03). On treatment, tumor response was assessed every 8 weeks for up to 12 months and afterward every 3 months by computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging of the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and all other sites of disease (RECIST v1.1). Quality-of-life assessment (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EORTC] Core Quality of Life Questionnaire QLQ-C30 and STO-22) was conducted every 8 weeks. Patients were followed up for up to 4 years for survival after first patient in. An independent data monitoring committee monitored safety data throughout the trial.

For translational analysis, baseline tumor tissue was obtained as well as peripheral blood for analysis of circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) prior to treatment initiation, after 2 weeks, after 8 weeks (not analyzed herein), and at progression and/or end of treatment. Methods of translational analyses are described in eMethods in Supplement 3.

The study was conducted in accordance with the standards of principles of good clinical practice, all applicable regulatory requirements, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval of the protocol was obtained from an independent ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment and before undergoing any study-specific procedures.

Statistical Analysis

The present trial was designed as a randomized phase 2 study, which aims to estimate the efficacy of 2 experimental regimens, each in relation to standard treatment results derived from historical data.12 The primary end point was OS. The trial was planned to increase the OS rate after 12 months from 55% with the current standard of care (fluoropyrimidine, platinum, trastuzumab based on the ToGA trial2) to 70% with both experimental treatments (hazard ratio [HR] of 0.6) with 80% power at a 1-sided 5% significance level, assuming an exponential survival distribution and applying a 1-sample log-rank test.13 Thus, 41 evaluable patients in each experimental treatment group were required. To account for potentially uninformative patients and a dropout rate of approximately 10%, 97 patients were recruited, and 88 were randomized. The final analysis was to be conducted based on 22 events per arm. Depending on the observed shape of the survival distribution, sensitivity analyses were planned.

Secondary end points were safety and tolerability (according to NCI CTCAE, version 4.03), PFS, duration of response (DOR) and unconfirmed ORR according to RECIST v1.1, quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO-22), and translational research end points. The time-to-event end points were counted from date of randomization (OS, PFS) or date of first response (DOR) until the event of the last observed date. The quality-of-life questionnaires were analyzed according to the respective scoring manuals based on observed data without imputation.14,15 Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

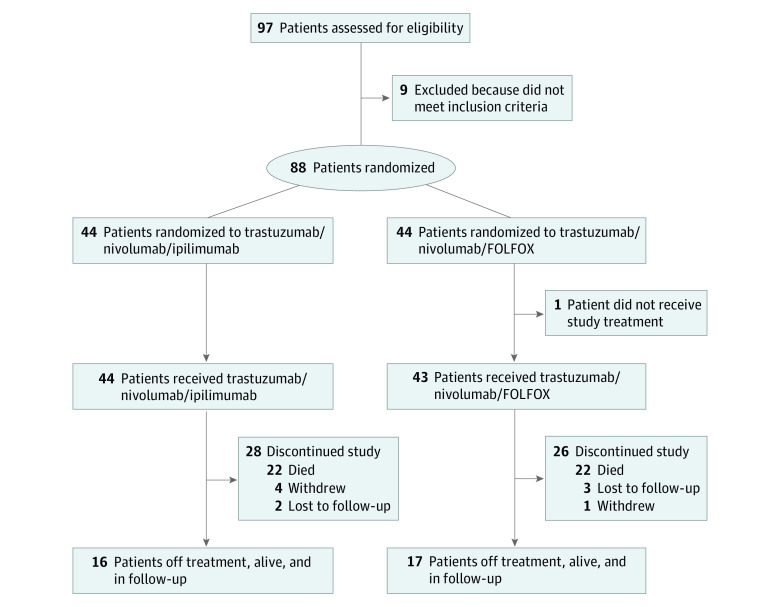

Patient Characteristics and Central Biomarker Testing

From March 2018 to May 2020, 97 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 88 were randomized in 21 German AIO sites (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between arms (Table 1). Median (range) age was 61 (41-80) years. The ECOG PS was 0 in 54 (61%) and 1 in 34 (39%) patients. Prior perioperative chemotherapy was applied in 30% of patients. Notably, retrospective central ERBB2 assessment showed ERBB2 negativity with ERBB2 IHC 1+ or IHC 2+ but no ISH amplification in 7 patients (of 84 available tumor blocks) and 1 patient with IHC 2+ and ISH not feasible. Central PD-L1 analyses (n = 82, 2 failed) showed combined positive score (CPS) of 0 in 23 (28%), 1 or greater in 59 (72%), and 5 or greater in 46 (56%) tumors. Median number of treatment cycles was 3 (9 weeks) in the ipilimumab arm (overall and for all drugs with no dose reduction) and 15 (30 weeks) in the FOLFOX arm (overall, 15 for trastuzumab and nivolumab with no dose reduction; 14 for fluorouracil/folinic acid with 12% of cycles reduced; and 8 for oxaliplatin with 9% of cycles dose reduced).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram of the INTEGA Trial.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trastuzumab/nivolumab/ipilimumab | Trastuzumab/nivolumab/FOLFOX | Total | |

| No. | 44 | 44 | 88 |

| Age, median (range), y | 63 (42-80) | 60 (41-79) | 61 (41-80) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 10 (23) | 8 (18) | 18 (20) |

| Male | 34 (77) | 36 (82) | 70 (80) |

| Localization | |||

| GEJ | 32 (73) | 34 (77) | 66 (75) |

| Stomach | 12 (27) | 10 (23) | 22 (25) |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0 | 26 (59) | 28 (64) | 54 (61) |

| 1 | 18 (41) | 16 (36) | 34 (39) |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 global health score, mean (SD) | 49.6 (25.1) | 51.9 (22.1) | NA |

| Primary tumor resection | 12 (27) | 12 (27) | 24 (27) |

| Prior perioperative treatment | 13 (30) | 13 (30) | 26 (30) |

| Grade | |||

| 1-2 | 19 (43) | 24 (55) | 43 (49) |

| 3 | 20 (46) | 18 (41) | 38 (43) |

| Missing | 5 (11) | 2 (4) | 7 (8) |

| Laurens type | |||

| Diffuse | 8 (18) | 6 (14) | 14 (16) |

| Intestinal | 23 (52) | 21 (48) | 44 (50) |

| Unknown | 13 (30) | 17 (38) | 30 (34) |

| ERBB2 (locally) | |||

| IHC 3+ | 38 (86) | 39 (89) | 77 (88) |

| IHC 2+/ISH+ | 6 (14) | 5 (11) | 11 (12) |

| RECIST v1.1 | |||

| Measurable | 40 (91) | 41 (93) | 81 (92) |

| Nonmeasurable | 4 (9) | 3 (7) | 7 (8) |

| Central assessment (84 available tumor blocks, 2 blocks failed PD-L1 staining) | |||

| ERBB2 (centrally) | |||

| IHC 3+ | 33 (77) | 30 (73) | 63 (75) |

| IHC 2+/ISH+ | 7 (16) | 6 (15) | 13 (15) |

| Negative | 3 (7) | 5 (12) | 7/8a (10) |

| PD-L1 (CPS) | |||

| 0 | 11 (26) | 12 (30) | 23 (28) |

| ≥1 | 31 (74) | 28 (70) | 59 (72) |

| ≥5 | 24 (57) | 22 (55) | 46 (56) |

| MSI-H | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| EBV positive | 3 (7) | 2 (5) | 5 (6) |

Abbreviations: CPS, combined positive score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire; GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; ISH, in situ hybridization; MSI-H, microsatellite instability high; NA, not applicable; PD-L1, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

ISH not feasible in 1 patient with ERBB2 IHC 2+.

Primary and Secondary End Points

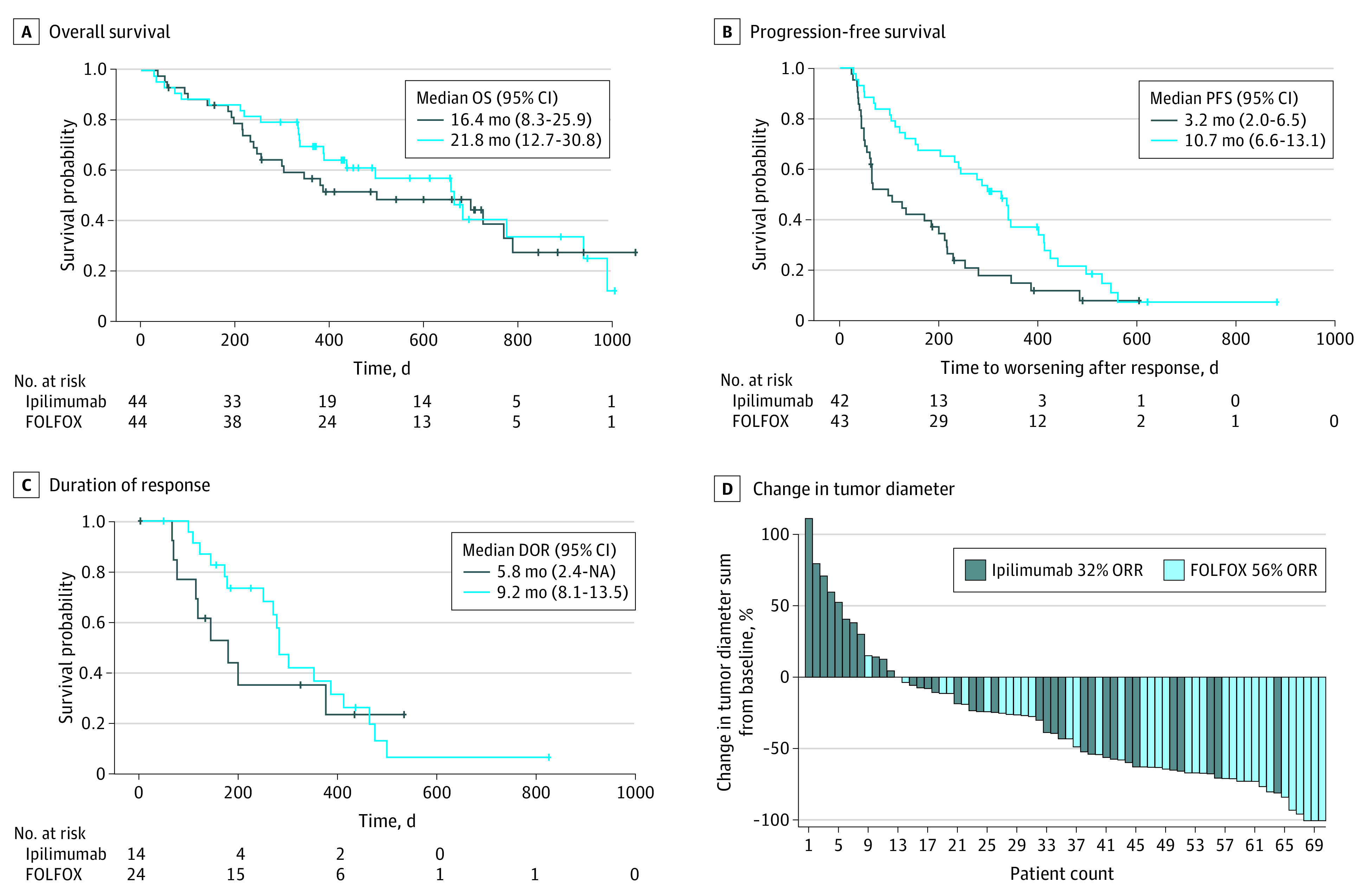

The efficacy results were determined in the intent-to-treat population (n = 88) after a median follow-up of 14.3 months (data lock date, March 6, 2021). The OS rate after 12 months was 57% (95% CI, 41%-71%) in the ipilimumab arm and 70% (95% CI, 54%-81%) in the FOLFOX arm (Figure 2A; eTable in Supplement 3). Thus, the estimated OS rate at 12 months was reached in the FOLFOX arm. The single-arm log-rank tests comparing with the historically based assumption for the standard treatment (ToGA) showed P values of .86 and .63 for the ipilimumab arm and the FOLFOX arm, respectively. Because of deviation of the survival distribution from the model assumptions, a binomial test was conducted as an exploratory sensitivity analysis, showing a significant improvement of the OS rate at 12 months for the FOLFOX arm compared with historical control with a P value of .03, and 55.4% as lower boundary of the CI, excluding the prespecified futility threshold with 95% confidence. In the ipilimumab arm, the OS rate at 12 months of 57% and the median OS of 16.4 (95% CI, 8.3-25.9) months was not improved but was within the numeric range compared with historical control.

Figure 2. Clinical Outcomes of Patients Treated in the INTEGA Trial.

Overall (OS) (A) and progression-free survival (PFS) (B) are presented for the ipilimumab vs the FOLFOX arm. Duration of response (DOR) is shown in panel C. The waterfall plot (D) shows responses in individual patients in the intent-to-treat population (2 patients—1 in each arm—were allowed to continue in the trial based on clinical response and local treatment applied beside Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors progression). The key in panel D reports the ORRs. NA indicates not applicable; ORR, overall response rate.

Secondary end points showed a median PFS of 3.2 (95% CI, 2.0-6.5) vs 10.7 (95% CI, 6.6-13.1) months (Figure 2B), a median DOR of 5.8 (95% CI, 2.4-not estimable) vs 9.2 (95% CI, 8.1-13.5) months (Figure 2C), and an ORR of 32% vs 56% (Figure 2D) in the ipilimumab arm vs FOLFOX arm, respectively. In patients with centrally confirmed ERBB2-positive tumors, ORR was higher with 63% in the FOLFOX arm (eTable in Supplement 3). Baseline quality of life was similar in both arms (EORTC QLQ-C30 global health score). Notably, patients in the FOLFOX arm showed a clinically relevant improvement compared with baseline in the first 4 months of treatment (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3).

Spider plots depicting the individual clinical courses of patients are shown for the ipilimumab arm in eFigure 3A in Supplement 3 and the FOLFOX arm in eFigure 3B in Supplement 3. Notably, some patients showed long-term benefit from the combination of ipilimumab, nivolumab, and trastuzumab.

Patients with ERBB2 IHC 3+ EGA showed significantly longer PFS and numerically longer OS than patients with ERBB2 IHC 2+/ISH-positive EGA (eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). Analysis of PD-L1 showed PD-L1 CPS 1 or greater in 59 (70%) and CPS 5 or greater in 46 (55%) patients. Expression of PD-L1 did not affect PFS or OS independently of treatment arm (eFigure 5 in Supplement 3).

Safety

The overall incidence of grade 3 or greater AE was similar in both arms (82% vs 88%) (Table 2). The most frequently observed treatment-related AE in the ipilimumab arm were anemia, infection, and diarrhea. Rates of grade 3 or greater autoimmune disorders (hepatitis, pneumonitis, colitis, and endocrine pathologies) were less than 10% in the ipilimumab arm and rarely seen in the FOLFOX arm (up to 2%). In the FOLFOX arm, most frequent AEs were leukopenia, infection, fatigue, and neuropathy. Overall, both arms tolerated treatment as expected. In the ipilimumab arm, 9 patients (21%) discontinued treatment owing to an AE compared with 7 patients (16%) in the FOLFOX arm. Overall, 47 patients (27 ipilimumab, 20 FOLFOX) discontinued treatment owing to progression or death. In the ipilimumab arm, 34 patients had a serious AE (SAE), which was related to treatment in 17 patients, compared with overall 28 patients with an SAE in the FOLFOX arm, of which 15 were treatment related. Overall, 5 fatal SAEs were noted, with 1 treatment-related SAE in the FOLFOX arm (tumor lysis).

Table 2. Toxic Effects According to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 4.03, Occurring in More Than 5% of Patients.

| Grade ≥3 AEs (safety population n = 87) | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Trastuzumab/nivolumab/ipilimumab (n = 44) | Trastuzumab/nivolumab/FOLFOX (n = 43) | |

| All grade ≥3 AEs | 36 (82) | 38 (88) |

| Treatment-related AEs | 20 (46) | 29 (67) |

| Leukopenia | 2 (5) | 10 (23) |

| Anemia | 5 (11) | 3 (7) |

| Infection | 5 (11) | 7 (16) |

| Fatigue | 3 (7) | 6 (14) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (14) | 2 (5) |

| Pyrexia | 1 (2) | 3 (7) |

| Neuropathy | 0 | 5 (11) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Hypertension | 0 | 3 (7) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 4 (9) | 0 |

| Colitis | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Endocrine disorders (hypophysitis/thyroiditis) | 3 (7) | 1 (2) |

| SAEs | 34 (77) | 28 (65) |

| Treatment-related SAEs | 17 (39) | 15 (35) |

| Fatal SAEs | 1 (2) | 4 (9) |

| Treatment-related fatal SAEs | 0 | 1 (2) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; SAE, serious AE.

Liquid Biopsy

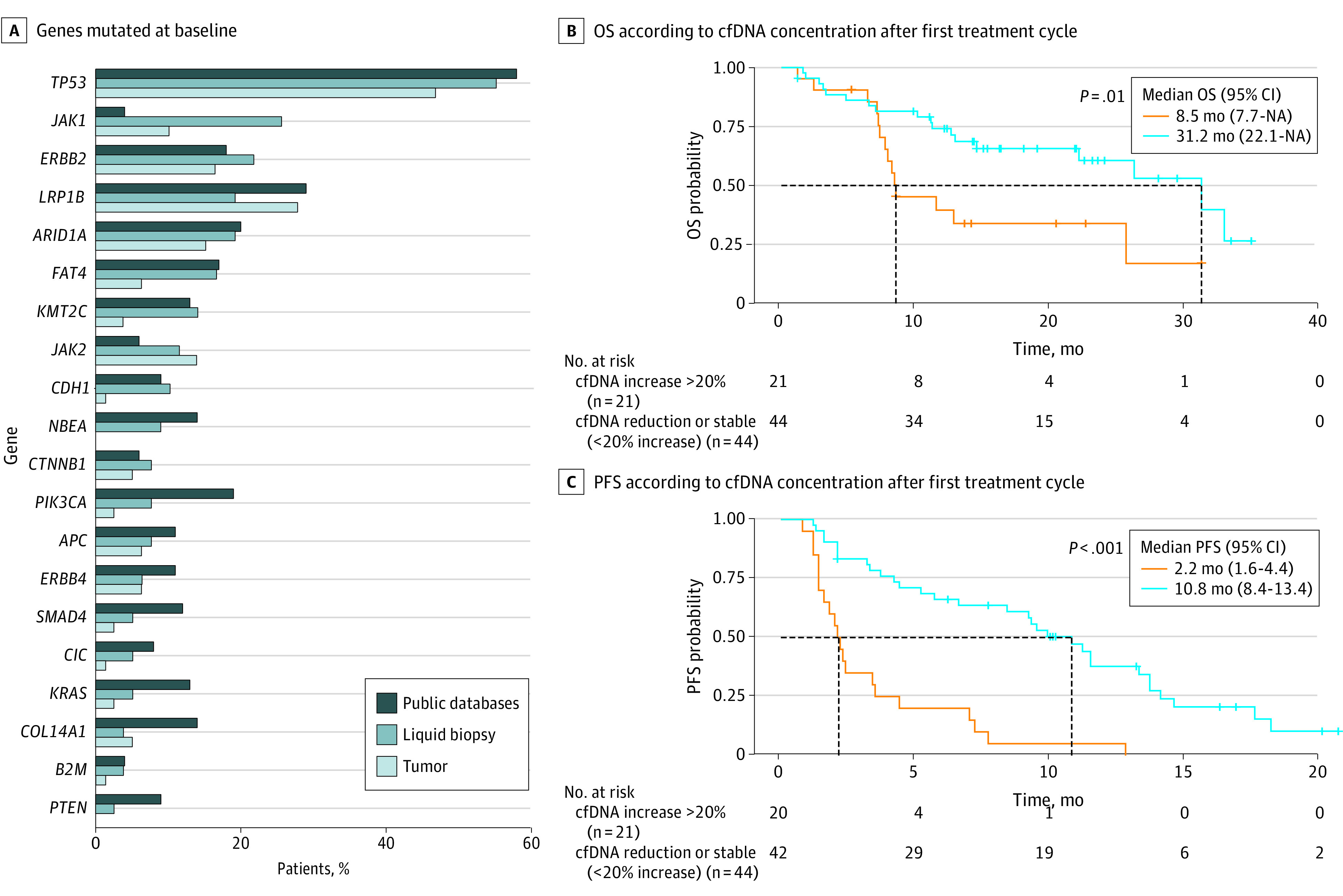

Tumor tissue and cfDNA (liquid biopsy) were profiled at baseline using a gene panel covering the most frequent driver and resistance sequence variations in EGA (APC, ARID1A, B2M, CTNNB1, ERBB2, ERBB4, FAT4, FCGR2A, FCGR3A, JAK1, JAK2, KMT2C, KRAS, LRP1B, PIK3CA, SMAD4, TP53). In 81 of 86 patients, sequence variations in baseline tumor tissue and/or liquid biopsy screening were identified, which overlapped in 69% of evaluable patients in at least 1 gene sequence variation. Sequence variation distribution in the INTEGA cohort was comparable with previously published data (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Mutational Profiling and Liquid Biopsy Disease Monitoring.

A, Percentage of patients with genes with sequence variations at baseline in liquid biopsy circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and in tumor tissue. Published data of the mutational landscape of driver genes in esophageal and gastric cancer were obtained from database cBioPortal.16,17 B and C, Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) of patients according to the level of cfDNA in blood after the first treatment cycle (2-3 weeks) vs baseline levels. Patients with increase in cfDNA concentration of greater than 20% (n = 21) were plotted vs patients showing cfDNA reduction or stability (n = 44). P values were calculated using log-rank test. Median survival is illustrated in months (vertical dashed lines); the horizontal dashed lines indicate the median of both curves. NA indicates not applicable.

Owing to high subclonal heterogeneity in gastric cancer,18 a cfDNA monitoring approach based on cfDNA blood concentrations rather than sequence variation tracking was applied.19,20,21 In approximately one-third of patients, cfDNA levels clearly increased by greater than 20% after the first treatment cycle (2-3 weeks). Early cfDNA increase (>20%) was a strong predictor of both shorter PFS and OS in the cohort (Figure 3B; eFigure 6 in Supplement 3). Patients showing cfDNA stability or reduction had a median PFS of 10.8 months and a median OS of 31.2 months vs only 2.2 and 8.5 months in those with early cfDNA increase. This effect was independent of treatment arm.

To explore mechanisms of acquired resistance, on-treatment liquid biopsies were searched for emerging sequence variations. Of 37 patients evaluable for liquid biopsy at disease progression on trastuzumab, 3 showed acquired truncating ERBB2 sequence variations, all of which leading to loss of the transmembrane domain, thereby abrogating membrane expression of ERBB2 (patients 11, 48, 50; eFigure 7 in Supplement 3). Moreover, patient 81 developed an ERBB2 H574L point mutation at the time of disease progression (eFigure 7 in Supplement 3). This sequence variation was located within the trastuzumab binding site. Binding studies using the recombinantly expressed mutant and wild-type ERBB2 extracellular domain showed significantly reduced trastuzumab binding to the mutant variant (eFigure 8 in Supplement 3). Together, this suggested that trastuzumab exerted substantial therapeutic pressure in both treatment arms, leading to the selection of resistance-mediating ERBB2-loss or epitope escape variants.

Discussion

The INTEGA trial was conducted in more than 20 German sites including universities, community hospitals, and private practices. It therefore reflects well the spectrum of daily clinical practice. This trial showed the feasibility of 2 experimental arms—the combination of trastuzumab, nivolumab, and either ipilimumab or FOLFOX—in the first-line treatment of ERBB2-positive EGA. The addition of nivolumab to a standard fluoropyrimidine/platinum and trastuzumab regimen (ToGA or control arm of JACOB trial) resulted in improved efficacy with an ORR of 56% (63% in centrally confirmed ERBB2-positive EGA) vs 47% to 48%, a median PFS of 10.7 vs 6.7 to 7 months, and median OS of 21.8 vs 14.2 to 16 months.2,3

In the ipilimumab arm, the main treatment-related AEs were autoimmune in nature, and in the FOLFOX arm, hematologic and oxaliplatinum-induced neuropathy. The overall incidence of AE grade 3 or worse was higher in both arms (>80%) compared with historical control (70%). Likewise, we recorded a slightly higher treatment discontinuation rate (21% in the ipilimumab arm and 16% in the FOLFOX arm vs 12%). Despite this, quality of life improved substantially within the first 4 months of treatment in the FOLFOX arm (>10 points), thus showing the overall acceptable tolerability of this regimen.

The FOLFOX arm showed similar survival outcomes compared with recently reported single-arm trials with pembrolizumab, trastuzumab, and chemotherapy, but a slightly lower ORR.8,9 The interim ORR of the randomized phase 3 KEYNOTE-811 was higher as well (74.4%).10 Differences in patient selection and ERBB2 positivity may have contributed to these differences. The local ERBB2 testing might have been of relevance, giving the option for an immediate treatment start und thus allowing for enrollment of patients with more aggressive or advanced tumors, which may not have been eligible for central testing and delay of treatment start by about 2 weeks in other trials. Moreover, the INTEGA trial enrolled patients even if only a RECIST nonmeasurable lesion was present (7 patients). The inability to define partial or complete responses in such patients may also have been a factor potentially explaining the comparable survival but slightly different response data compared with other immunotherapy trials in ERBB2-positive EGA. The ipilimumab arm showed no improvement in OS and rather poor ORR and PFS compared with historical control and with the FOLFOX arm. These results are in line with the recently presented data from CheckMate 649 evaluating the same nivolumab and ipilimumab schedule in a ERBB2-negative patient cohort (without trastuzumab).22 Despite some patients showing long-lasting responses (eFigure 3B in Supplement 3), an up-front chemotherapy-free strategy replacing chemotherapy by ipilimumab is not advisable, at least in unselected patients with ERBB2-positive EGA. However, selecting patients for ERBB2 3+ and CPS positivity may enable application of a chemotherapy-free regimen, as was recently shown for margetuximab and retifanlimab (ORR, 52.5%; median PFS, 6.4 months).23

To identify sensitivity or resistance markers, we investigated PD-L1 and ERBB2 expression/amplification and performed mutational analysis of tumor material as well as liquid biopsies on treatment. While patients with ERBB2 IHC 3+ tumors did better than those with (ERBB2 amplified) tumors that showed lower ERBB2 expression (IHC 2+), PD-L1 CPS was not predictive of outcome in both experimental arms that contained checkpoint-inhibiting antibodies. Mutational tumor profiles were comparable with previously published data and did not reveal any relevant associations.24,25,26 Notably, neither single nucleotide polymorphisms resulting in higher affinity Fc γ receptor 2a and 3a binding to trastuzumab27 nor mutant LRP1B that had previously been reported to enhance the effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors across tumor entities28 predicted outcomes in the INTEGA cohort (data not shown). Interestingly, however, increase in cfDNA levels over the first treatment course was significantly associated with shorter PFS and OS. The early monitoring of cfDNA may therefore allow for immediate determination of treatment efficacy. Patients with increasing levels of cfDNA by at least 20% were progressing with a chance of about two-thirds at their first imaging. To search for acquired resistance, we analyzed cfDNA at the time of disease progression and detected truncating or epitope loss variants in 4 patients. To our knowledge, this is the first trial describing such ERBB2 sequence variations associated with resistance to ERBB2-directed treatment. The patients with sequence variations leading to the loss of the transmembrane domain interestingly exerted a PFS of 10 to 13 months, thus potentially indicating delay in the development of resistance to ERBB2 targeting by the addition of PD-1 inhibition despite rather low PD-L1 CPS (0-2). Larger randomized trials with or without PD-1 inhibition in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy may shed further light on the mechanisms of resistance in ERBB2-positive EGA.29

Limitations

This study has limitations. Based on the exploratory phase 2 design, patient number was limited, and comparisons were with historical control for both arms. The central ERBB2 assessment revealed a negative/not evaluable status in 8 of 84 patients, leading to some imbalance between the arms.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical trial, the addition of nivolumab to trastuzumab and chemotherapy in first-line ERBB2-positive EGA resulted in long PFS and OS and should be further developed in a phase 3 trial. The chemotherapy backbone is needed and should not be replaced by ipilimumab in an unselected ERBB2-positive patient population.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods.

eTable. Efficacy in intent to treat population (ITT) and subgroups

eFigure 1. Treatment regimen applied in the trial

eFigure 2. Quality of life according to EORTC QLQ C30 Global Health Score

eFigure 3. The spider plots for the Ipi (A) and the FOLFOX arm (B) show responses in individual patients in the intent to treat population

eFigure 4. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for patient subsets with different HER2 expression levels

eFigure 5. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for patient subsets with different PD-L1 expression levels

eFigure 6. cfDNA dynamics per treatment arm

eFigure 7. Truncating and epitope escape mutations of HER2 associated with disease progression on trastuzumab-containing regimen

eFigure 8. Recombinant expression of Fc-Her2 wild-type and Fc-Her2-His574Leu protein

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. ; ToGA Trial Investigators . Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687-697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabernero J, Hoff PM, Shen L, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab and chemotherapy for HER2-positive metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (JACOB): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(10):1372-1384. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30481-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10294):27-40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, et al. ; KEYNOTE-590 Investigators . Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2021;398(10302):759-771. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01234-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janjigian YY, Bendell J, Calvo E, et al. CheckMate-032 study: efficacy and safety of nivolumab and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with metastatic esophagogastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(28):2836-2844. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.6212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varadan V, Gilmore H, Miskimen KL, et al. Immune signatures following single dose trastuzumab predict pathologic response to preoperative trastuzumab and chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(13):3249-3259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janjigian YY, Maron SB, Chatila WK, et al. First-line pembrolizumab and trastuzumab in HER2-positive oesophageal, gastric, or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):821-831. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30169-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rha SY, Lee C, Kim H, et al. A multi-institutional phase Ib/II trial of first-line triplet regimen (pembrolizumab, trastuzumab, chemotherapy) for HER2-positive advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer (PANTHERA trial): molecular profiling and clinical update. Abstract 218. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(3 suppl). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.3_suppl.218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janjigian YY, Kawazoe A, Yanez P, et al. Pembrolizumab plus trastuzumab and chemotherapy for HER2+ metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction (G/GEJ) cancer: initial findings of the global phase 3 KEYNOTE-811 study. Abstract 4013. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15 suppl). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tintelnot J, Goekkurt E, Binder M, et al. Ipilimumab or FOLFOX with nivolumab and trastuzumab in previously untreated HER2-positive locally advanced or metastatic EsophagoGastric Adenocarcinoma—the randomized phase 2 INTEGA trial (AIO STO 0217). BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):503. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06958-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riechelmann R, Araujo R, Hinke A. The many different designs of phase II trials in oncology. In: Araujo RLC, Riechelmann RP, eds. Methods and Biostatistics in Oncology: Understanding Clinical Research as an Applied Tool. Springer Nature; 2018:189-202. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J. A new one-sample log-rank test. J Biom Biostat. 2014;5(4):210-214. doi: 10.4172/2155-6180.1000210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal and Quality of Life Groups . Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(15):2260-2268. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401-404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269):pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murugaesu N, Wilson GA, Birkbak NJ, et al. Tracking the genomic evolution of esophageal adenocarcinoma through neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(8):821-831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng J, Holland-Letz T, Wallwiener M, et al. Circulating free DNA integrity and concentration as independent prognostic markers in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169(1):69-82. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4666-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kienel A, Porres D, Heidenreich A, Pfister D. cfDNA as a prognostic marker of response to taxane based chemotherapy in patients with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2015;194(4):966-971. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodall J, Mateo J, Yuan W, et al. ; TOPARP-A investigators . Circulating cell-free DNA to guide prostate cancer treatment with PARP inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(9):1006-1017. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janjigian YY, Ajani J, Moehler M, et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus chemotherapy (chemo) or ipilimumab (ipi) vs chemo as first-line (1L) treatment for advanced gastric cancer/gastroesophageal junction cancer/esophageal adenocarcinoma (GC/GEJC/EAC): CheckMate 649 study. Abstract. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(suppl 5):S1329-S1330. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.2131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catenacci D, Park H, Shim BY, et al. Margetuximab (M) with retifanlimab (R) in HER2+, PD-L1+ 1st-line unresectable/metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEA): MAHOGANY cohort A. Abstract. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(suppl 5):S1043-S1044. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang DS, Liu ZX, Lu YX, et al. Liquid biopsies to track trastuzumab resistance in metastatic HER2-positive gastric cancer. Gut. 2019;68(7):1152-1161. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janjigian YY, Sanchez-Vega F, Jonsson P, et al. Clinical next generation sequencing (NGS) of esophagogastric (EG) adenocarcinomas identifies distinct molecular signatures of response to HER2 inhibition, first-line 5FU/platinum and PD1/CTLA4 blockade. Abstract 6120. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 6). doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw371.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513(7517):202-209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavin PG, Song N, Kim SR, et al. Association of polymorphisms in FCGR2A and FCGR3A with degree of trastuzumab benefit in the adjuvant treatment of ERBB2/HER2-positive breast cancer: analysis of the NSABP B-31 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(3):335-341. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown LC, Tucker MD, Sedhom R, et al. LRP1B mutations are associated with favorable outcomes to immune checkpoint inhibitors across multiple cancer types. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(3):e001792. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung HC, Bang YJ, S Fuchs C, et al. First-line pembrolizumab/placebo plus trastuzumab and chemotherapy in HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer: KEYNOTE-811. Future Oncol. 2021;17(5):491-501. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eMethods.

eTable. Efficacy in intent to treat population (ITT) and subgroups

eFigure 1. Treatment regimen applied in the trial

eFigure 2. Quality of life according to EORTC QLQ C30 Global Health Score

eFigure 3. The spider plots for the Ipi (A) and the FOLFOX arm (B) show responses in individual patients in the intent to treat population

eFigure 4. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for patient subsets with different HER2 expression levels

eFigure 5. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for patient subsets with different PD-L1 expression levels

eFigure 6. cfDNA dynamics per treatment arm

eFigure 7. Truncating and epitope escape mutations of HER2 associated with disease progression on trastuzumab-containing regimen

eFigure 8. Recombinant expression of Fc-Her2 wild-type and Fc-Her2-His574Leu protein

Data Sharing Statement